Published online Jun 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i6.107033

Revised: April 8, 2025

Accepted: April 28, 2025

Published online: June 27, 2025

Processing time: 77 Days and 20.8 Hours

Although laparoscopic gastrolithotomy had been widely used in clinical practice, uncommon postoperative complications still require vigilance by medical staff.

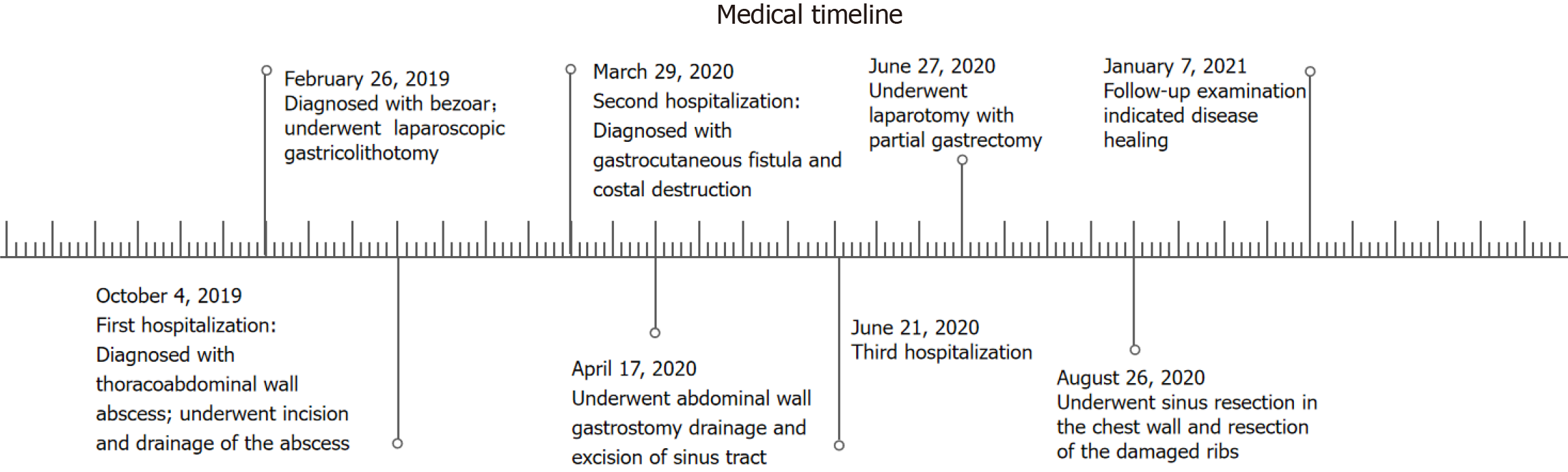

Here we report a 67-year-old man who suffered for 18 months and underwent surgery several times due to a rare and undetected complication of laparoscopic gastricolithotomy. He presented to multiple hospitals because of sustained left upper quadrant abdominal pain one month after laparoscopic gastricolithotomy due to a large gastric bezoar caused by unrestrained eating of black dates and was diagnosed with possible intercostal neuritis. Many painkillers were used to relieve his symptoms but the condition progressed. Seven months after surgery, he was hospitalized as skin ulceration occurred in the left upper abdominal wall and was subsequently diagnosed with a massive thoracoabdominal wall abscess. One year after surgery, irreversible costal destruction was demonstrated. Both lesions were finally proved to be secondary damage due to a rare chronic gastro-abdominal wall fistula related to laparoscopic gastricolithotomy and the diameter of the gastric fistula reached 2 centimeters (cm). The patient was ultimately cured but underwent multi-regional incisions and drainage of the abscess, drainage of the gastric fistula, partial gastrectomy and removal of damaged ribs, and was fo

This may be the first reported case of a chronic thoracoabdominal abscess and costal destruction caused by an undetected chronic gastro-abdominal wall fistula. We believe that this is a novel type of gastric fistula and the diagnosis and treatment were challenging.

Core Tip: We report a 67-year-old man who underwent surgery several times for a rare and undetected complication of laparoscopic gastricolithotomy. He presented to multiple hospitals because of sustained left upper quadrant abdominal pain one month after laparoscopic gastricolithotomy and was subsequently diagnosed with a massive thoracoabdominal wall abscess seven months after surgery, and irreversible costal destruction one year after surgery. Both lesions were finally confirmed to be secondary damage due to a rare chronic gastro-abdominal wall fistula related to laparoscopic gastricolithotomy and the diameter of the gastric fistula reached 2 cm.

- Citation: Kang YZ, Sun JH. Chronic gastro-abdominal wall fistula with secondary massive thoracoabdominal wall abscess and costal destruction after laparoscopic gastricolithotomy: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(6): 107033

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i6/107033.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i6.107033

Although laparoscopic gastricolithotomy has been widely used in clinical practice, uncommon postoperative complications still require vigilance by medical staff. Here we report a 67-year-old man who suffered for 18 months and underwent several operations due to a chronic gastro-abdominal wall fistula and its secondary effects of a massive thoracoabdominal wall abscess and irreversible costal destruction after laparoscopic gastricolithotomy. Chronic gastro-abdominal wall fistula has rarely been reported after gastric surgery.

A 67-year-old man complained of pain in the left upper abdominal wall for more than 6 months, and local skin ulceration for more than 10 days.

The patient was admitted to our hospital on October 4, 2019 with a massive thoracoabdominal wall abscess and anemic appearance. He had presented to multiple hospitals because of sustained left upper quadrant pain six months ago and was diagnosed with possible intercostal neuritis. He took various painkillers, which did not prevent his condition from progressing. More than 10 days before he was hospitalized, skin ulceration occurred in the left upper abdominal wall and was the reason of his admission.

The patient underwent laparoscopic gastricolithotomy for a large gastric bezoar (10 cm × 6 cm × 5 cm) on February 26, 2019. He visited the hospital due to upper abdominal fullness and discomfort for more than 2 months after unrestrained eating of black dates, and aggravation with pain for more than 1 month. Gastroscopy revealed bezoar and he underwent surgery. Under laparoscopy, the large curvature of the anterior wall of the stomach was opened by an electric hook, and the bezoar with a size of 10cmx6cmx5cm in the gastric cavity was found. A 5-cm incision in the left upper abdomen was made, and a protective sleeve was placed to protect the incision. The gastric bezoar was removed with oval forceps. The gastric wall tissue was closed by interrupted full-thickness suture with No. 4 silk suture, and then the seromuscular layer was embedded with barbed suture. A drainage tube was placed at the greater curvature of the stomach and fixed in the left abdominal puncture site. After checking the equipment and gauze, the abdominal incision was sutured layer by layer. The drainage tube was removed on the 9th postoperative day.

The patient had previously been well and had no family history of the disease.

The patient was of slim build and weighed 57 kg, with stable vital signs. He appeared to be anemic and palpebral conjunctiva were pale. An old surgical scar was visible on the left upper abdomen. Anterior and lower chest wall and the entire abdominal wall was red and edematous. Skin gangrene and a rupture approximately 1.5 cm in diameter was seen in the left upper quadrant, with a small amount of foul-smelling purulent fluid oozing. The abdominal wall could be fluctuated and the skin temperature was slightly increased. There was positive tenderness all over the abdomen without obvious rebound pain and muscle tension. Murphy's sign was negative. The enlarged liver was identified under the right costal margin, and the spleen was not palpated. There was no obvious pain in the liver, spleen and kidney area, and bowel sounds were approximately 3 per minute. Edema was seen in both lower limbs.

The laboratory data obtained on admission revealed an obviously elevated white blood cell count of 33.2 × 109 with 99.5% neutrophils and marked reductions in hemoglobin (74 g/L) and red blood cell count (3.06 × 1012). Liver function showed a decline in albumin at 22 g/L (normal range: 40-55 g/L), and other indices were normal. Renal function showed a slightly raised creatinine level of 107.9 μmol/L (normal range: 57-97 μmol/L) and other indices were normal. Blood clotting function showed marked elevations in activated partial thromboplastin time (40.7 seconds, normal range: 22.7-31.8 seconds) and fibrinogen (6.89 g/L, normal range: 1.8-3.5 g/L). Procalcitonin was 0.93 ng/mL (normal range: 0-0.05 g/L).

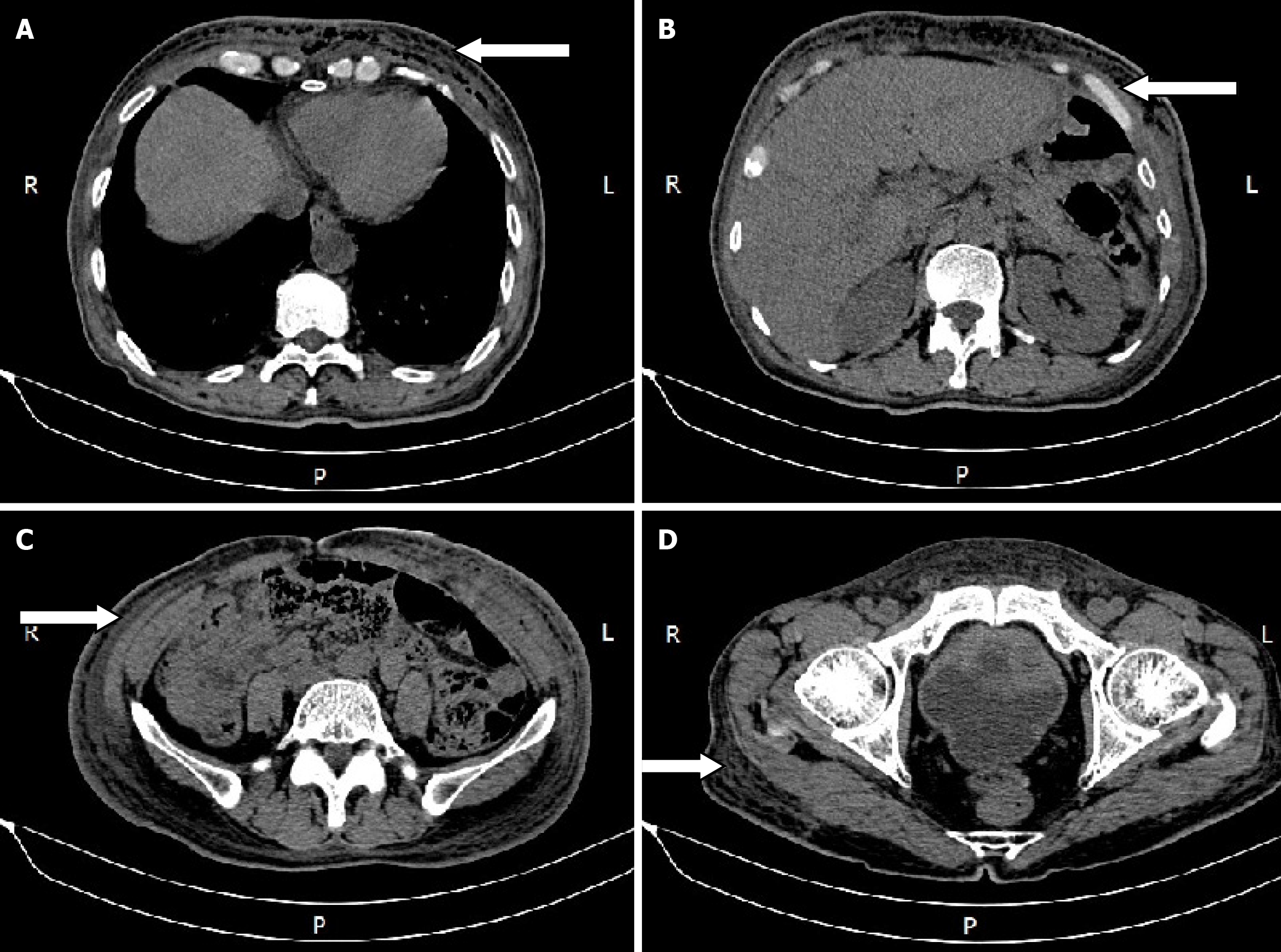

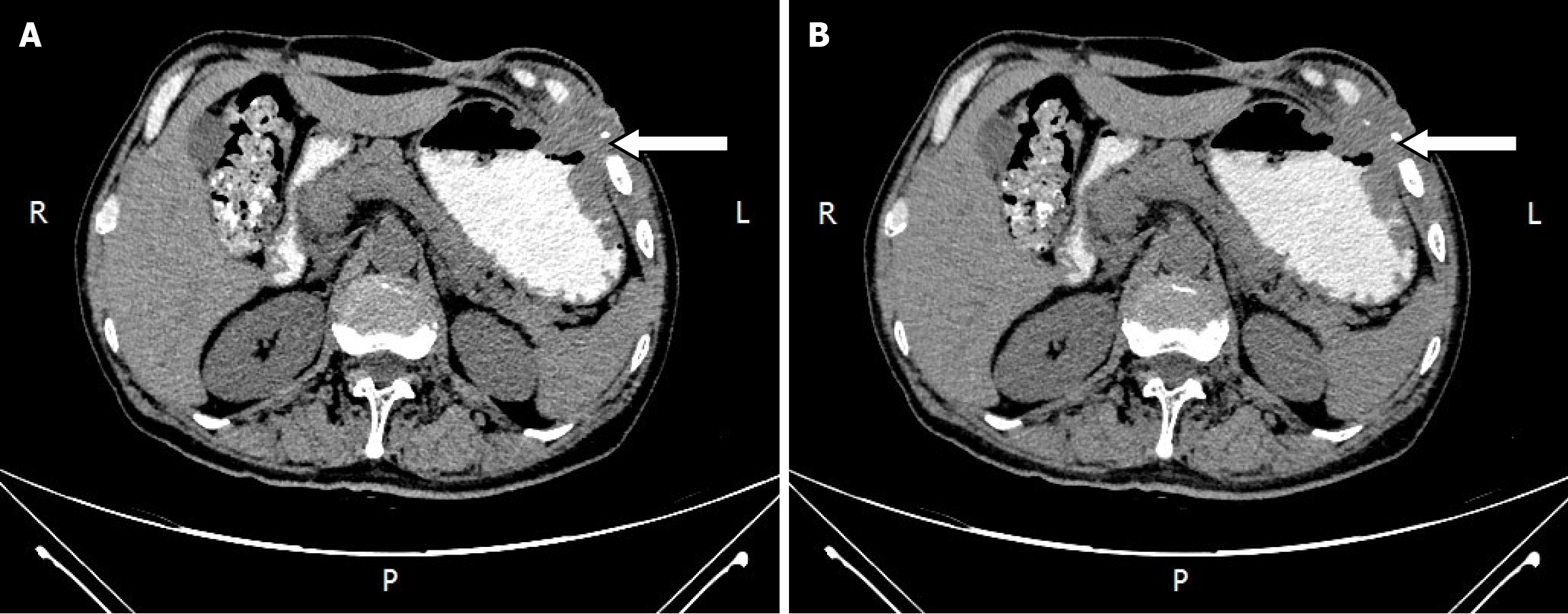

An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed diffuse edema with pneumatosis of the antero-inferior chest wall and abdominal wall, and cellulitis was considered (Figure 1).

Chest and abdominal wall abscess.

In view of the patient's extensive abscess and poor nutritional status, multiple incisions and drainage were performed in stages combined with antibiotics, meanwhile, a nutritionist was consulted to provide an adequate infusion of intravenous nutrient solution and albumin supplementation. Pus culture was positive for Pseudomonas aeruginosa. After more than a month of treatment, his condition significantly improved and he was discharged on November 22, 2019 and outpatient dressing changes were then initiated. However, the patient's dressing changes lasted over four months.

Chief complaints: On March 29, 2020, the patient was again admitted to our hospital due to left upper abdominal rupture and the incision on the adjacent left chest wall had not healed. An abdominal or chest wall sinus was suspected because of intermittent overflow of pus. The patient's temperature was normal.

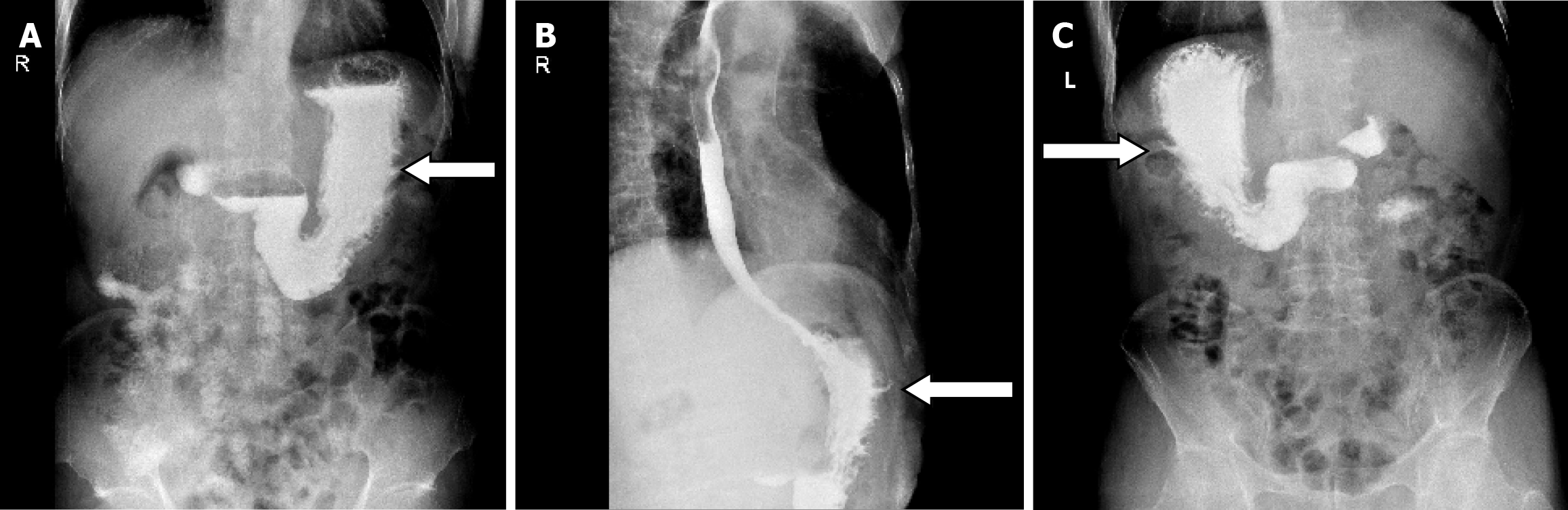

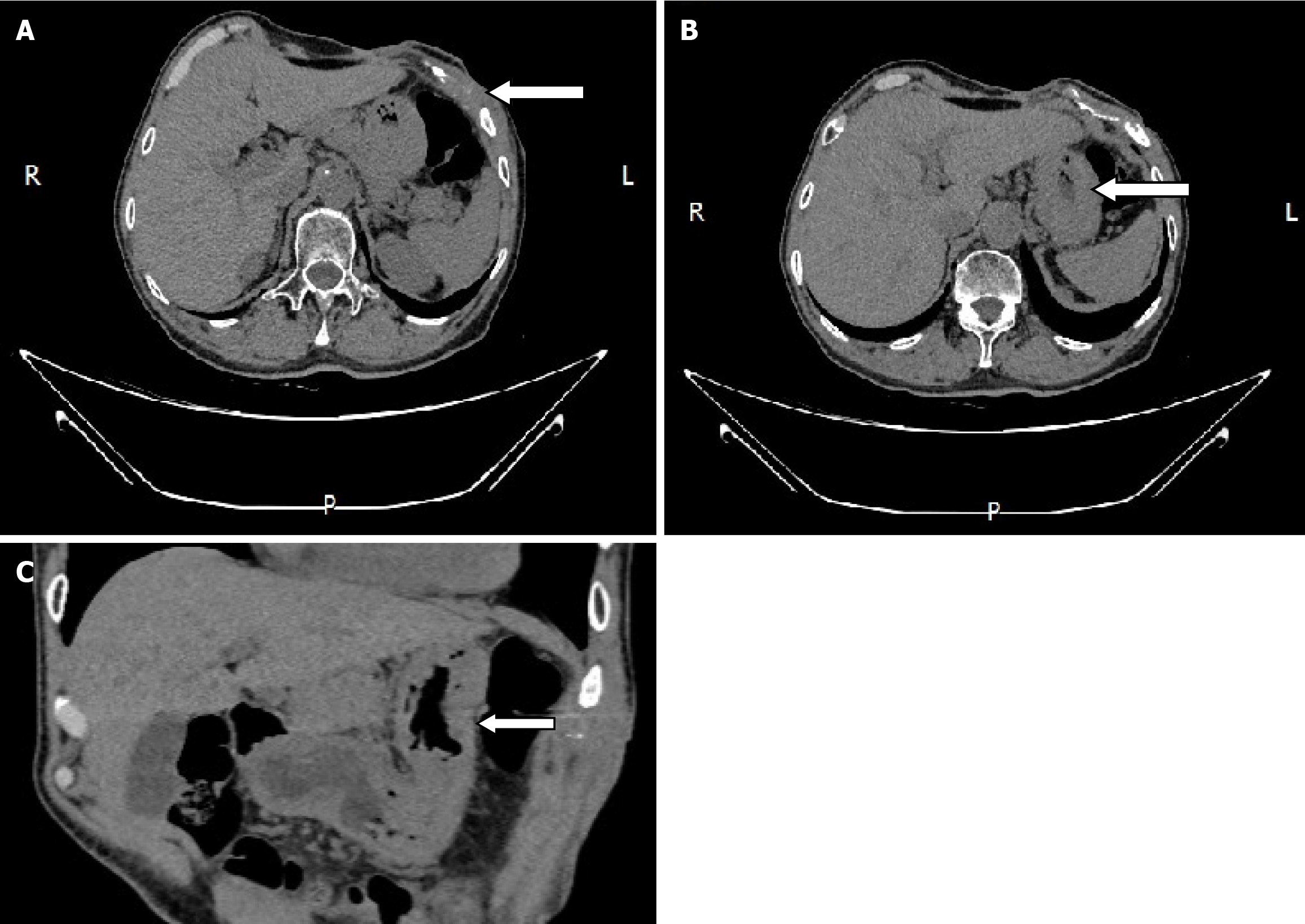

Laboratory and imaging examinations: The laboratory data obtained on this admission revealed a hemoglobin of 117

Diagnosis and treatment: According to the results of the abovementioned examinations, we unexpectedly determined the presence of a gastro-abdominal fistula. Its internal opening was in the greater curvature of the stomach body and the initial unhealed rupture on the left upper abdomen may be the external opening. As the incision on the adjacent left chest wall had not healed either and rib destruction was shown on the CT scan, we suspected an associated sinus in the chest wall. Unfortunately, although all available examinations including oral methylene blue and trans-sinus radiography had been performed, how it went through the abdominal wall as well as adjacent chest wall and whether branches remained was uncertain, which directly affected treatment. Following the exclusion of gastric malignancy, most doctors recommended an exploratory laparotomy, and the surgeons advocated gastric fistula drainage and gradual replacement of drainage tubes of smaller diameter until healed. We strongly recommended a thorough exploratory laparotomy, but the patient and his family chose gastric fistula drainage due to the fear of more invasive surgery.

On April 17, 2020, we performed trans-abdominal wall gastric fistula drainage and debridement of the chest sinus. In detail, we carefully explored inside via the left upper abdominal rupture using a blunt drainage tube with an appropriate diameter until the breakthrough was felt, and the tail end of the tube was inserted into a syringe. When withdrawing the syringe, viscous gastric juice was collected which demonstrated the formation of a gastric-abdominal fistula. During exploration through the unhealed incision on the adjacent chest wall, this revealed the existence of a chest sinus up to the ribs and intercostal muscles, but no communication with the stomach. This indicated that non-healing of the chest wall incision may be the result of broken ribs forming a sinus in the chest wall. The sinus tract was scratched with a spoon and the tissue was retained for pathological examination.

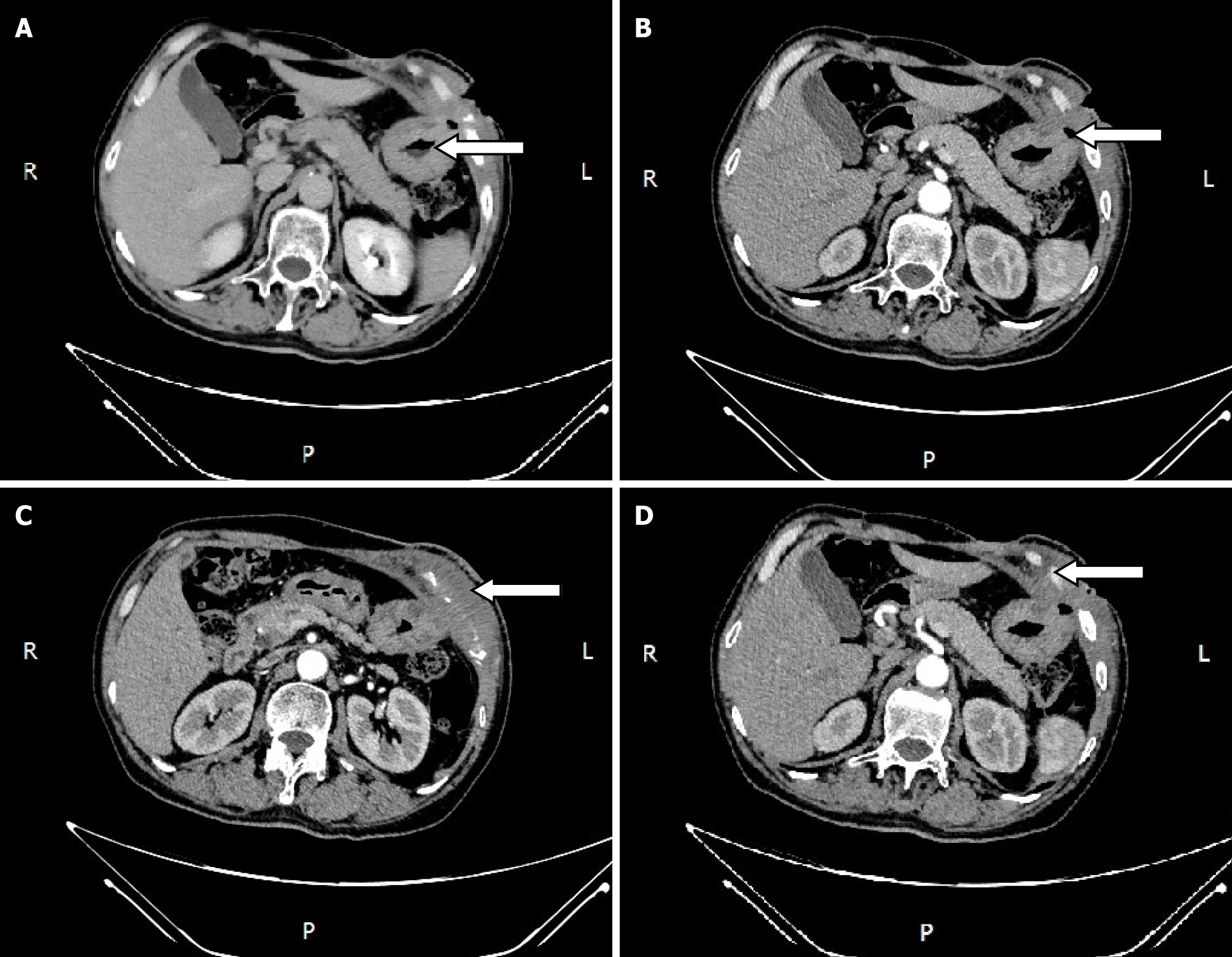

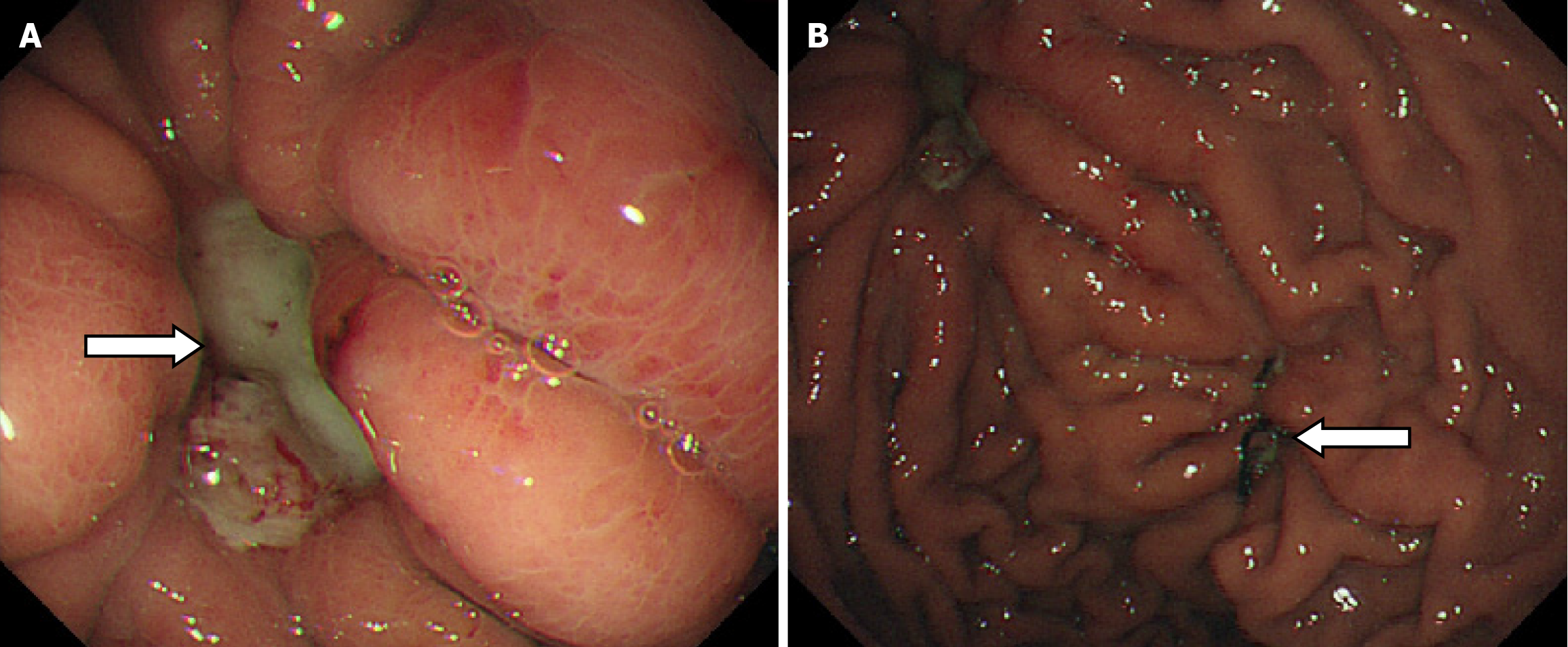

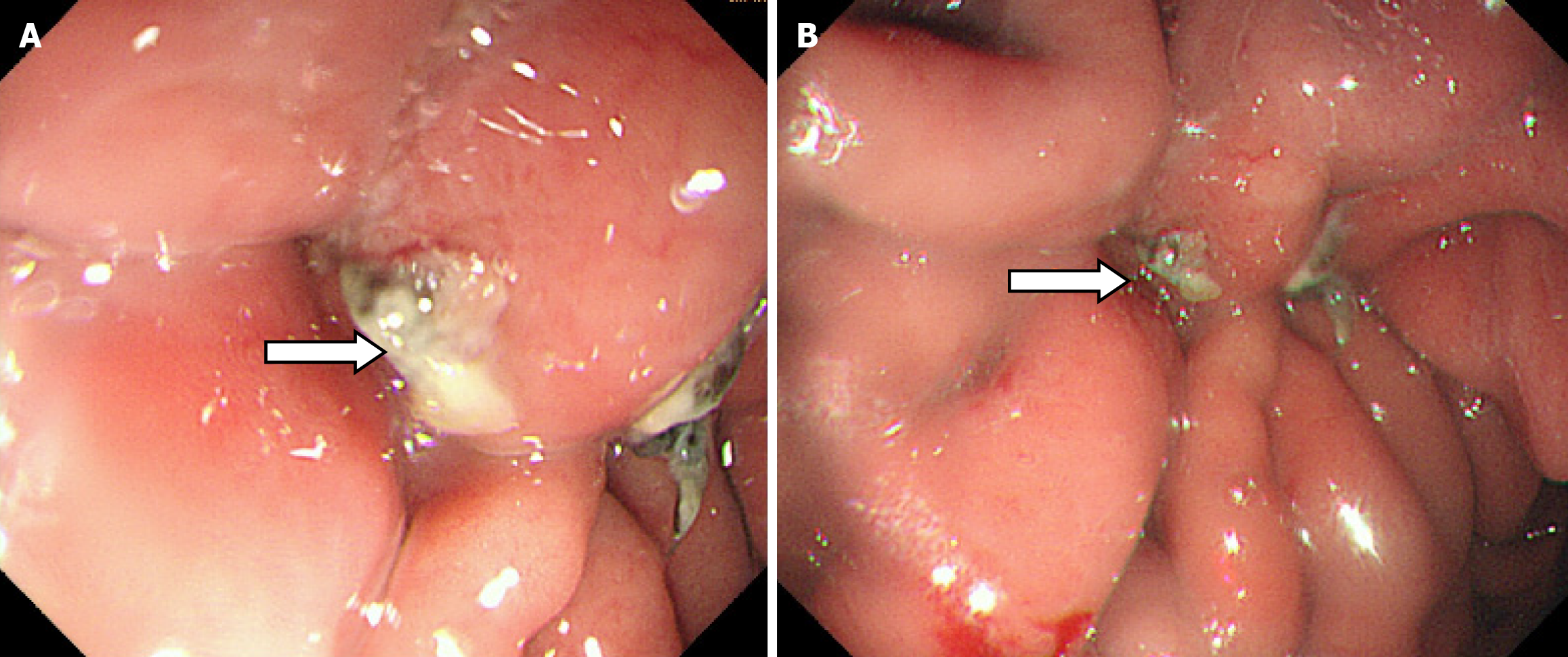

During the postoperative fasting period, we consulted with a nutritionist again. The energy and nitrogen sources were supplied according to the patient's disease status until he returned to a roughly normal diet and then changed to oral enteral nutrition. Drainage tubes of smaller diameter were placed successively and then removed. Reexamination by abdominal CT confirmed that the thoracoabdominal wall swelling had improved (Figure 5), gastric endoscopy verified gastric ulcer improvement and the gastric fistula was not observed at this time (Figure 6). The patient’s clinical symptoms, especially pain, were alleviated. Pathological examination of the sinus showed fibrous and inflammatory granulation tissue with a giant cell reaction. His condition improved and he was again discharged on June 17, 2020.

On July 21, 2020, the patient was again hospitalized due to the unsatisfactory outcome of more than one month of outpatient treatment. The abdominal wall fistula and incision on the adjacent left chest wall had not completely healed. The patient and his family eventually agreed to an exploratory laparotomy. As the rib CT scan displayed destruction of the left 7th, 8th and 9th anterior ribs and costal cartilage, we consulted with thoracic surgeons and determined that rib surgery could be performed right after exploratory laparotomy.

Therefore, on July 27, 2020, surgery was conducted. Intraoperative exploration found that the abdominal omentums and other organs were adhered to the thoracoabdominal wall as well as each other, the greater curvature of the gastric body was especially seriously adhered to the thoracoabdominal wall. A full-thickness defect of the gastric wall of approximately 2 cm in diameter was observed on the greater curvature of the gastric body. On further examination, the defect was confirmed to correspond with the external ostium on the left upper abdominal wall. Thus, we performed a partial gastrectomy, and the damaged peripheral hard gastric wall tissue was removed, the gastric wall was then sutured with full thickness suturing to close the defect and the muscle layer was embedded. The sinus tissue was then peeled off layer by layer with an electric knife, and the internal ostium of the thoracoabdominal sinus was scratched with a scraping spoon. During the operation, the thoracic surgeon was consulted and decided to postpone the rib related surgery. As expected, after approximately 7 days of fasting and intravenous nutrition, the patient resumed eating and recovered well postoperatively. On August 26, 2020, thoracic surgeons performed sinus resection in the chest wall and resection of the damaged ribs.

Although the patient was discharged with mild pain on September 14, 2020, we were confident that he would have a complete recovery and it was proved by reexamination 3 months later (Figure 7). The patient was then followed up for more than 4 years without recurrence. Time-line about diagnosis and treatment of the patient was shown on Figure 8.

Gastrolithiasis mainly relates to the consumption of foods that contain tannic acid, pectin and gum, such as hawthorn, persimmon and black dates. Tannic acid and gastric acid can combine with protein and therefore form tannic acid protein which is water-insoluble and precipitates in the stomach. When pectin and gum meet acid, they form a gel, which can bind the precipitated tannic acid protein which can accumulate with food residues to form a gastrolith[1]. Laparoscopic gastricolithotomy had been widely used particularly when conservative treatment, such as injection of Coca–Cola, and endoscopic surgery fail in clinical practice[2-5]. The possibly of postoperative complications require vigilance by medical staff.

It is well-known that gastric fistula usually occurs early after surgery and can lead to diffuse peritonitis, incision infection and other complications; therefore, identification of gastric fistula does not seem difficult. Huang et al[6] reported an abdominal abscess caused by Raoultella ornithinolytica secondary to a gastric fistula after left lateral hepatectomy and cholecystectomy, which was characterized by an acute onset of infection resulting from a rare bacterium. Chronic gastro-abdominal wall fistula has rarely been reported. Even if a few authors have reported and discussed the treatment of chronic gastric fistula[7,8], they merely focused on the chronic gastric fistula itself, and did not specifically elaborate the complications caused by chronic gastric fistula. To our knowledge, our case may be the first report of a chronic thoracoabdominal abscess and costal destruction caused by an undetected chronic gastro- abdominal wall fistula.

We named the disease gastro-abdominal wall fistula because it resulted from a defect in the gastric wall and ultimately ruptured from the left upper abdominal wall although imaging examinations showed that the fistula mainly passed through the chest wall. It is interesting that our patient's primary clinical symptom of pain, began one month after surgery and abscess on the chest and abdominal wall developed more than seven months later and multiple imaging studies performed earlier showed no significant gastric abnormalities or evidence of gastric fistula. We believe that the most probable reason was that as the gastric wall was close to the thoracoabdominal wall post-surgery, and the early gastric fistula may have been so tiny that the leakage of gastric juice could have been trapped during the process of tissue repair. However, the continuous leakage of gastric juice, which has strong erosion activity was the reason for long-term pain, which corroded outward gradually through each layer of the thoracoabdominal wall, spread within the loose subcutaneous tissue and eventually broke the skin, and that was the immediate cause of his first hospitalization. In addition, the absence of bacterial infection at the early stage described previously may be another important reason for chronic progression of the disease. We carried out bacterial culture several times throughout the treatment process, and only once discovered Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the specimen collected during the first hospitalization. No positive pathogenic bacteria including Pseudomonas aeruginosa were detected in subsequent specimens and no significant abnormalities in inflammatory markers were found during the second and third hospitalization, although antibiotics were withdrawn at that time. Therefore, bacterial infection may be a secondary change in the gastro-abdominal wall fistula and its presence accelerated the course of the disease in the later stage and caused the patient's nutritional status to worsen. The swelling of tissue surrounding the fistula further contributed to the difficulty in early diagnosis.

In addition, we noted that there are reports of a gastric fistula secondary to drainage tube penetration[9,10]. Drains are widely used in abdominal surgery in order to remove any collections or secretions and can alert to hemorrhage or anastomotic leakage. However, erosion into adjacent tissues is one of the rarest complication that may occur, with a risk of fistula development, particularly when drains are placed near upper digestive anastomoses and sutures[11]. However, the reported drainage tube related fistulas all occurred before the drainage tube was removed or in the early stage of the disease. In our patient, the initial symptom occurred well after the drain was removed, and there was no large increase in drainage fluid before drain removal. We consider that a drainage-induced fistula was unlikely. We also studied the surgical record of laparoscopic gastricolithotomy and found that the seromuscular layer was embedded with a barbed suture after interrupted full-thickness suturing of gastric wall tissue with No. 4 silk sutures. We suspected that the seromuscular layer closed by the barbed suture gradually became loose due to contraction and relaxation of the stomach itself. In addition, the patient's symptoms had existed for more than two months before laparoscopic gastricolithotomy. It is well-known that the ulcer can develop when the mucosal defense is overwhelmed by noxious factors such as H. pylori infection, use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and/or gastric acid hypersecretion and retention of giant bezoar as seen in the present case. It cannot be excluded that the giant gastric stone caused gastric ulcer due to repeated friction or persistent compression to the gastric mucosa although it was not revealed during endoscopy and surgery. The healing of a gastric ulcer is a regeneration process that includes cell proliferation, migration, re-epithelialization, formation of granulation tissue, angiogenesis, and interactions among various cells and the matrix[12]. Any error in any link may lead to failure of healing. The occurrence of gastric ulcer led to the damage of gastric mucosal barrier, the decline of defense ability, and the enhancement of gastric acid and pepsin invasion to the gastric wall. Gradually, penetrating ulcers developed and eventually involved the chest and abdominal wall. However, formation of the gastric fistula may be the result of multiple factors, and these require further investigation.

It was difficult to identify the original cause of the disease, and treatment was also challenging. During the patient's first hospitalization, we focused on treatment of the abscess, and given the patient's disease state at that time, even if there was evidence of a gastro-abdominal fistula, drainage may still have been the only option, but not during the second hospitalization because his massive chest and abdominal wall abscess had been well-controlled and nutritional status had greatly improved. Based on this and due to rib destruction, a thorough exploratory laparotomy was recommended with the purpose of relieving pain, reducing the secondary lesion and shortening the treatment time. Nevertheless, the patient and his family chose gastric fistula drainage with the hope of avoiding more invasive surgery. However, he subsequently underwent exploratory laparotomy. It was quite astonishing that a full-thickness defect in the gastric wall with a diameter of approximately 2 cm was observed on the greater curvature of the gastric body during the operation despite gastroscopy after treatment by gastric drainage revealed a reduction in the size of the lesion. We considered that any procedure (such as drainage) other than a partial gastrectomy to close the internal orifice of the fistula would be futile and sinus resection combined with resection of the damaged ribs should be carried out in order for the patient to be cured. The patient was finally cured after 18 months of treatment and several surgeries.

We believe that the diagnosis and treatment in this case will be helpful for clinical doctors. First, treatment of any unexplained abscess simultaneously requires careful investigation of the cause despite there being no direct evidence pointing to previous surgery. Second, effective treatment should be based on a favorable nutrition management and a full understanding of fistula, including its origin, size and shape. Due to the limitations of any imaging examination and insufficient experience regarding the diagnosis of gastric fistula, if some aspects are unclear, we recommend direct surgical exploration and determination of the surgical method according to the intraoperative situation on the premise that the patient can tolerate the operation in order to avoid more serious secondary damage caused by delayed and ineffective treatment. Moreover, to prevent such complications, before surgery, it is necessary to formulate a detailed treatment plan, including surgical, and suture protocol (particularly selecting appropriate suture lines and suture methods), and appropriate drainage tube placement to reduce the occurrence of complications. In addition, we should be aware of the possibility of gastric wall damage caused by bezoar itself, and clarify whether bezoar has secondary gastric ulcer and other complications. Finally, we must pay full attention to the psychological state of the patient, help the patient to create a positive treatment atmosphere, and obtain good cooperation.

We believe that this case may be the first report of chronic thoracoabdominal abscess and costal destruction caused by an undetected chronic gastro-abdominal wall fistula. This is a novel type of gastric fistula, and clinicians should be aware of the occurrence of this type when managing such patients and make correct decisions regarding the diagnosis and treatment.

| 1. | Hakoda A, Takayama K, Sasaki S, Mori Y, Tanaka H, Sugawara N, Iwatsubo T, Ota K, Nishikawa H. A case of gastrolithiasis produced by a 5-day diet. DEN Open. 2025;5:e70012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ladas SD, Triantafyllou K, Tzathas C, Tassios P, Rokkas T, Raptis SA. Gastric phytobezoars may be treated by nasogastric Coca-Cola lavage. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:801-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ladas SD, Kamberoglou D, Karamanolis G, Vlachogiannakos J, Zouboulis-Vafiadis I. Systematic review: Coca-Cola can effectively dissolve gastric phytobezoars as a first-line treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:169-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ota K, Kawaguchi S, Iwatsubo T, Nishida S, Tanaka H, Mori Y, Nakajima N, Hakoda A, Sugawara N, Kojima Y, Takeuchi T, Sakaguchi M, Higuchi K. Tannin-phytobezoars with Gastric Outlet Obstruction Treated by Dissolution with Administration and Endoscopic Injection of Coca-Cola(®), Endoscopic Crushing, and Removal (with Video). Intern Med. 2022;61:335-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Krausz MM, Moriel EZ, Ayalon A, Pode D, Durst AL. Surgical aspects of gastrointestinal persimmon phytobezoar treatment. Am J Surg. 1986;152:526-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Huang Q, Zhang J, Liao G. Abdominal abscess caused by Raoultella ornithinolytica secondary to postoperative gastric fistula: case report and review of literature. BMC Infect Dis. 2024;24:363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rayman S, Staierman M, Ben-David M, Assaf D, Hazzan D, Carmeli I, Rachmuth J, Keidar A. Laparoscopic revision to total gastrectomy or fistulo-jejunostomy as a definitive surgical procedure for chronic gastric fistula after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2020;16:1893-1900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jovani M, Zhang L, Huang Y, Kumbhari V. Multi-layer endoscopic suturing: a novel method of gastric fistula closure. Endosc Int Open. 2021;9:E1520-E1523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shao HJ, Lu BC, Xu HJ, Ruan XX, Yin JS, Shen ZH. Gastric fistula secondary to drainage tube penetration: A report of a rare case. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:2176-2178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Paraskevopoulos JA, Samoilis S, Papadakis G, Kostopoulos O, Kalimeris S. Drainage tube perforation of the stomach: an exceptionally rare complication. J Trauma. 2000;48:330-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | González-Pinto I, González EM. Optimising the treatment of upper gastrointestinal fistulae. Gut. 2001;49 Suppl 4:iv22-iv31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tarnawski AS, Ahluwalia A. The Critical Role of Growth Factors in Gastric Ulcer Healing: The Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms and Potential Clinical Implications. Cells. 2021;10:1964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |