Published online May 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i5.103078

Revised: January 23, 2025

Accepted: March 14, 2025

Published online: May 27, 2025

Processing time: 196 Days and 9.7 Hours

The surgical management of incidentally detected Meckel diverticulum (MD) during appendectomy remains controversial. We present a case report alongside an analysis of the ACS-NSQIP database to evaluate postoperative outcomes associated with concomitant Meckel diverticulectomy during laparoscopic appen

We report the case of a 34 year-old woman presenting with acute appendicitis and an incidentally detected MD. The patient presented to the emergency department with right lower quadrant pain. Computed tomography revealed acute appen

Resection of incidental MD can be performed during laparoscopic appendectomy without significant morbidity or mortality.

Core Tip: Incidental Meckel diverticulum (MD) is rare but can be encountered during routine abdominal surgical procedures. The surgical management of incidental MD remains debated. We report a case of resection of an incidentally detected MD during laparoscopic appendectomy with no complications on the 6-year follow-up. ACS-NSQIP analysis demonstrated that concurrent incidental Meckel diverticulectomy with laparoscopic appendectomy does not increase morbidity and mortality. However, Meckel diverticulectomy with laparoscopic appendectomy increases resource utilization. We recommend resection on the basis of individualized patient’s factors and acknowledge that incidental Meckel diverticulectomy can be efficiently and safely performed in selected patients.

- Citation: Nguyen SHT, Wheelwright M, Vakayil V, Meshram P, O’Donnell R, Harmon JV. Concomitant resection of Meckel diverticulum during laparoscopic appendectomy: Retrospective propensity-matched ACS-NSQIP study and a case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(5): 103078

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i5/103078.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i5.103078

Surgical resection of an incidentally detected Meckel diverticulum (MD) during appendectomy for acute appendicitis remains controversial. We present a case report and analyzed the ACS-NSQIP database to examine postoperative complications and patient outcomes associated with concomitant Meckel diverticulectomy during appendectomy.

Although generally asymptomatic, MD can present with painless bleeding, diverticulitis, perforation, bowel obstruction, intussusception, fistula, and neoplasm[1-3]. Two of the most common symptoms in children include bleeding and obstruction, whereas in up to 58% of adults with symptomatic MD, Meckel diverticulitis is reported to be the presenting feature[4]. Mechanical obstruction, volvulus, and intestinal strangulation may result from intussusception due to MD[5]. Moreover, MD may present with symptoms indicative of enterocyst or intestinal–umbilical fistula[6].

A consensus that complicated and symptomatic MD should be resected exists; however, whether incidentally detected asymptomatic MD should be resected remains unclear. Risk scoring systems to resect asymptomatic MD have been described however there are few registry database analyses analyzing incidental MD resection outcomes[6]. We here compared postoperative complications and patient outcomes associated with concomitant Meckel diverticulectomy during primary laparoscopic appendectomy compared with laparoscopic appendectomy alone (AA).

The patient’s chief complaint was right lower quadrant abdominal pain.

The patient was a 34-year-old female who presented with a 24-h history of right lower quadrant abdominal pain to a community hospital setting. Fevers, chills, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal bloating were not reported.

The patient had no allergies and no prior medical and surgical history.

She was a nonsmoker and did not drink alcohol. Family history was noncontributory.

On admission, the following were the patient’s vital signs: Temperature: 97.7 °F; heart rate: 77 beats/min; blood pressure: 140/90 mmHg; respiratory rate: 16 breaths/min; and oxygen saturation: 100% at room air. On palpation, her abdomen was soft and not distended, with localized right lower quadrant pain without guarding or rebound tenderness. No rovsing sign was elicited. The extremities were warm to touch and well perfused.

Her urinalysis result was normal, and her peripheral white blood cell count was within normal institutional limits at 6900/μL.

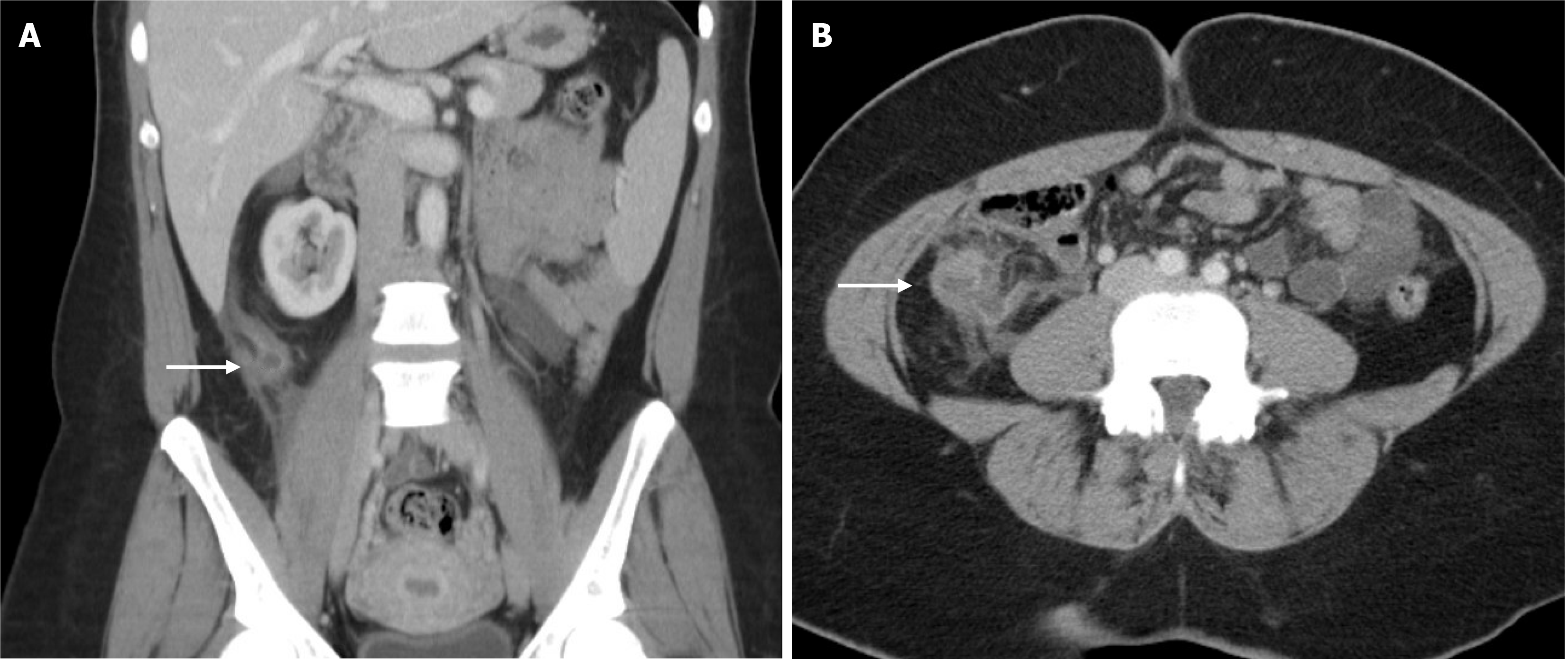

Abdominal computed tomography revealed a fluid-filled and distended appendix measuring 1.2 cm in diameter with adjacent fluid and fat stranding; no extraluminal gas was detected (Figure 1).

The final diagnosis was perforated appendicitis with associated incidental MD.

The patient proceeded to the operating room for standard laparoscopic appendectomy. Intraoperatively, the tip of the appendix was distended and inflamed. A contained perforation was revealed. The base of the appendix, which was grossly normal, was divided using a laparoscopic stapler. The mesoappendix was divided using a LigaSure© energy device. The appendix was removed and placed in an Endocatch bag. A protrusion from the small bowel was noted extending along the antimesenteric side of the ileum consistent with an MD. A diverticulum was laparoscopically palpated and contained a firm mass. To decrease the risk of future complications and owing to the described firmness, the diverticulum was removed. Using a laparoscopic stapler, diverticulectomy was performed in a longitudinal manner parallel to the long axis of the bowel on the antimesenteric surface. The MD was removed from the abdomen and placed in an Endocatch pouch. The procedure was completed, and the patient was subsequently taken to the post anesthesia care unit.

Pathological examination of the appendix demonstrated acute perforated appendicitis, and the MD demonstrated intestinal mucosa only without evidence of malignancy. The patient was discharged on the same day as her surgery, and her post operative course was uneventful. She did not have any complications on 6 year follow up.

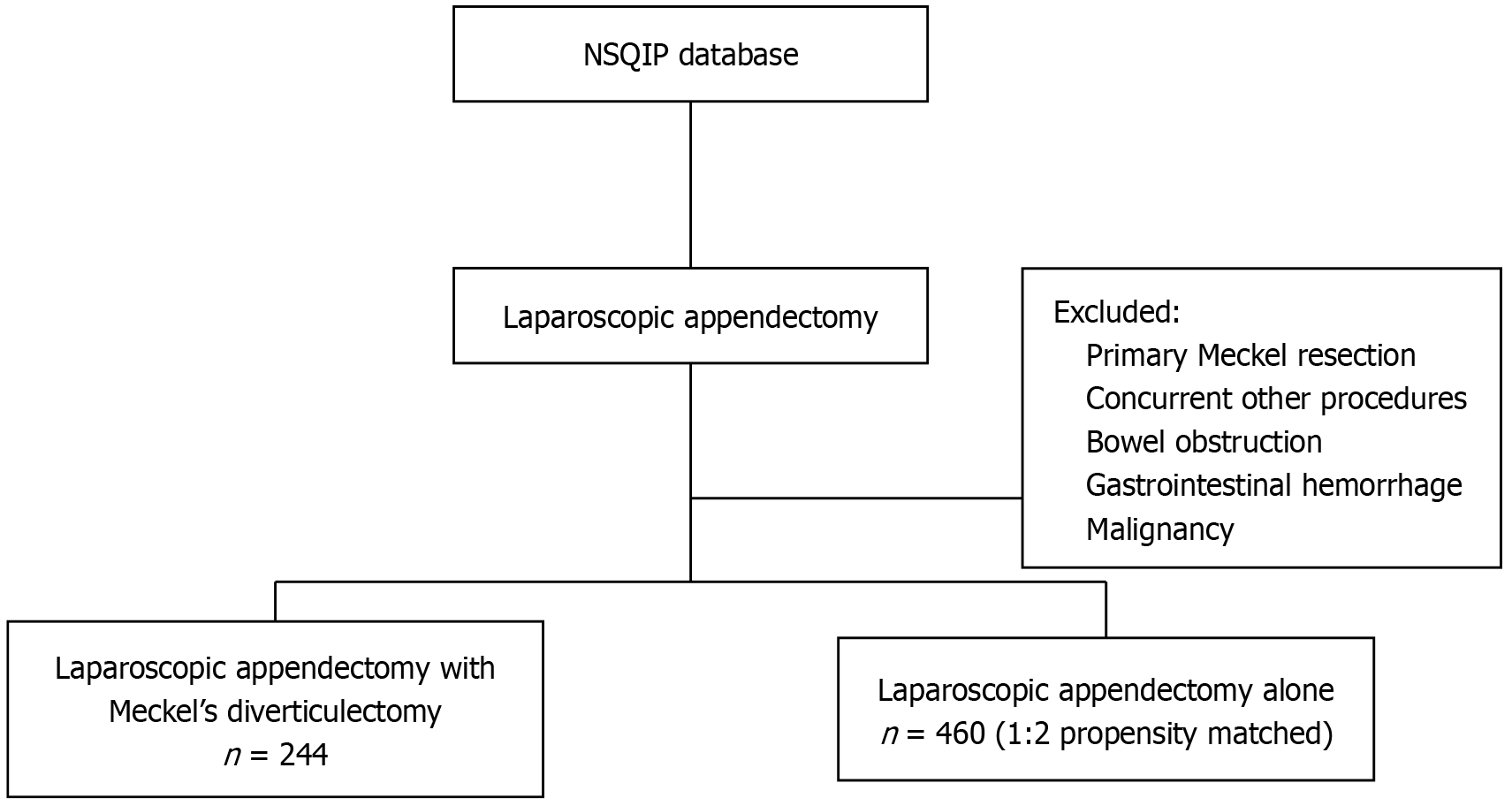

In addition to presenting our case report, we also performed a retrospective analysis of the ACS-NSQIP database during the 12 years preceding our patient’s procedure as these were the data available at the time of surgery. This database comprises over 140 patient variables from over 650 institutions nationally. Using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes, we identified the following two adult patient cohorts: Patients undergoing concomitant Meckel diverticulectomy with appendectomy (MA) and those undergoing laparoscopic AA. All patients who underwent additional concurrent procedures, primary Meckel diverticulectomy, had bowel obstruction, had gastrointestinal hemorrhage, or had a cancer diagnosis were excluded (Figure 2). We performed propensity score matching for the patients in these two cohorts. Baseline demographics, comorbidities, and 30-day postoperative morbidity and mortality were compared. Furthermore, to compare between patient outcomes and 30-day postoperative morbidity and mortality, we performed univariate and 1:2 propensity-matched analyses. Lastly, operative time, the total length of hospital stay, 30-day postoperative infectious complications, 30-day non-infectious complications, and 30-day mortality were evaluated.

Using the χ2 and Fisher exact tests, we compared individual clinical comorbidities and measured differences between groups for categorical variables. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for analyzing continuous nonparametric variables, and independent-sample t-tests were employed for analyzing parametric continuous variables. Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 25, IBM, Armonk, NY, United Staes). We performed propensity score matching to reduce the effects of baseline variable heterogeneity and selection bias. To calculate the propensity scores, a logistic regression model with a maximum likelihood technique was used and cohorts were matched by demographics. We stratified our study population by type of surgery (MA vs AA), matched each patient who underwent MA to two patients who underwent AA (1:2 ratio) according to the closest-estimated propensity score, and applied the nearest-neighbor matching technique without replacement using a caliper setting of 0.2.

We identified 244 patients who underwent combined laparoscopic appendectomy and Meckel diverticulectomy and 460 patients who underwent laparoscopic AA (Table 1). Patients undergoing combined laparoscopic appendectomy and Meckel diverticulectomy showed a statistically significant increase in operative time (66.2 ± 28.5 vs 53.4 ± 26.9 min; P < 0.001) and a statistically significantly longer hospital length of stay (4.1 ± 3.9 vs 2.8 ± 3.7 days; P < 0.001). No difference in mortality was observed between the two groups.

| Appendectomy alone (n = 460) | Meckel + appendectomy (n = 244) | P value | |

| Age (years) | 39.6 ± 16.9 | 38.9 ± 15.9 | |

| Operative time (mins) | 53.4 ± 26.9 | 66.2 ± 28.5 | < 0.001 |

| Total hospital length of stay (days) | 2.8 ± 3.7 | 4.1 ± 3.9 | < 0.001 |

| Re-operation, n (%) | 5 (1.1) | 7 (3.3) | 0.072 |

| 30-day mortality, n (%) | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 1.000 |

Analyzing rate of postoperative infectious complications between AA and MA revealed no significant differences (Table 2). Neither AA nor MA had increased amounts of all three types of surgical infection (superficial, deep, and organ space). No cases of wound dehiscence were reported. The AA group had a higher rate of sepsis and septic shock than the MA group (6.1% vs 3.0% for sepsis; 1.0% vs 0% for septic shock, respectively); however, neither of these findings were significant.

| Appendectomy alone (n = 460) | Meckel + appendectomy (n = 244) | P value | |

| Superficial surgical site infection | 9 (2.0) | 4 (1.6) | 0.776 |

| Deep incisional infection | 3 (0.7) | 5 (2.0) | 0.091 |

| Organ space infection | 15 (3.3) | 5 (2.0) | 0.477 |

| Wound dehiscence | 0 | 0 | - |

| Pneumonia | 6 (1.3) | 1 (0.4) | 0.432 |

| Urinary tract infection | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 1.000 |

| Sepsis | 28 (6.1) | 7 (3.0) | 0.071 |

| Septic shock | 5 (1.0) | 0 | 0.170 |

Similarly, rate of postoperative non-infectious complications did not significantly differ between the AA and MA groups (Table 3). Overall, few non-infectious complications were noted, with pulmonary embolism being the most common (n = 3).

| Appendectomy alone (n = 460) | Meckel + appendectomy (n = 244) | P value | |

| Prolonged ventilation (> 48 h) | 0 | 0 | - |

| Unplanned re-intubation | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 1.000 |

| Progressive renal insufficiency | 0% | 0 | - |

| Acute renal failure | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 1.000 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 0.961 |

| Cardiac arrest requiring CPR | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 1.000 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 0.347 |

| DVT requiring therapy | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 1.000 |

| Blood transfusion (intra/postoperative period) | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.4) | 1.000 |

We present a 34-year-old woman who received care for a contained perforated acute appendicitis with an intraoperatively detected MD. This case demonstrates the safe and effective removal of an incidentally detected MD when combined with laparoscopic appendectomy. The patient was routinely discharged from the post-anesthesia care unit. The procedure lasted for < 30 min, which is lower than the means of both MA and AA on ACS-NSQIP analysis. Pathological examination revealed that the MD measured 2 cm × 1.5 cm × 1 cm without any evidence of malignancy or ulceration. The firmness of the MD noted intraoperatively may be explained by the relatively small lumen compared with the intestinal tissues in the MD or a transit bolus of the intraluminal content, thereby making the MD appear more robust than the adjacent small bowel. Additionally, the surgery remained laparoscopic, and tactile was limited. Studies have reported that patients’ estimated lifetime complication rate from unresected MD is approximately 4%[5]. Considering our patient’s asymptomatic MD intraoperatively, she may have been asymptomatic for her lifetime. However, the noted firmness with a suspicion of malignancy should indicate further investigation and resection. Conversion to open surgery may have helped differentiate the MD’s firmness. At the 6-year follow-up, the patient showed no clinical signs of stenosis at resection, adhesive small bowel obstruction, or other small bowel MD resection-associated complications. Her postoperative course was uneventful.

MD is a true diverticulum of the mid-to-distal ileum, indicating the persistence of the vitelline duct from fetal development. The incomplete regression of this duct causes an MD remnant[5,7]. Identified by Johann Friedrich Meckel in 1809, MD affects up to 3% of the world population[5]. The lifetime risk of complications is approximately 4%, decreasing to as low as 1% after the age of 40 and becoming negligible after the age of 70[1,6,8].

MD-associated symptoms are frequently nonspecific and can mimic acute appendicitis[9]. In up to 40% of patients with Meckel diverticulitis, acute appendicitis is the presumed preoperative diagnosis[10]. Approximately 4% of patients with symptomatic MD are correctly diagnosed preoperatively[5,7]. MD is most frequently incidentally identified as an asymptomatic MD in patients undergoing abdominal surgery for other conditions, as observed in our case presentation. A retrospective series of 1,476 patients showed that 84% of MD resections were classified as incidental and asymptomatic[6].

An incidental MD resection can be performed by simple diverticulectomy or segmental bowel resection and primary anastomosis. To determine the efficacy of these two surgical resection techniques, Varcoe et al[11] proposed the “height-to-diameter” ratio (HDR), with segmental bowel resection being recommended when the HDR is > 2 over simple diverticulectomy. This recommendation is based on the need for complete resection of the heterotopic mucosa contained in the MD and surrounding small bowel tissues when the HDR is > 2. We were unable to compare these two surgical techniques using the ACS-NSQIP database, and limited data were available to compare the safety and efficacy associated with simple diverticulectomy vs segmental bowel resection and primary anastomosis. In our case, diverticulectomy was performed via longitudinal stapled resection.

The need to resect incidental asymptomatic MD remains debated. Zani et al[12] reported that 758 incidental MD resections are needed to prevent one death. Cullen et al[13] observed that symptomatic Meckel diverticulectomies posed an operative mortality of 2% and morbidity of 12% compared with incidental diverticulectomies with an operative mortality of 1% and morbidity of 2%. Complication rates have been reported as high as 3% when cancer is identified within the MD, with 33% of the cases being carcinoid tumors[14,15]. These studies have concluded that the complications associated with MD, including those due to malignancy, outweigh the risks of resection. In our analysis of the ACS-NSQIP database, MA did not significantly increase the 30-day postoperative morbidity and mortality compared with AA, which is consistent with those of other studies[16,17]. Although we observed that the total operating time and length of hospital stay were significantly longer for those undergoing MA, our case demonstrates an operative time below the mean with a same day discharge.

The severity of the patient’s original clinical presentation, the patient’s age and comorbid status, and the features of the patient’s MD that may impact the likelihood of the patient presenting later with a complicated MD should be considered in the decision to resect incidental MD[6]. Our data suggest that the decision to operate should be individualized as we noted increased utilization without major patient complication. Other studies have suggested implementing a risk-scoring algorithm to assist in intraoperative decision-making. Park et al[6] recommended resecting asymptomatic MDs when the patient and the MD had the following risk factors: Age < 50 years, male sex, MD length > 2 cm, or the appearance of abnormal tissues in the MD. Robijn et al[18] proposed a risk-scoring algorithm with similar risk factors as follows: Age < 45 years, male sex, MD length > 2 cm, or the presence of fibrous bands. Grimaldi et al[19] cautioned against resecting incidental asymptomatic MDs owing to legal concerns when the resection of the MD is not included in the patient’s surgical consent. Though legality of resection of incidental findings may vary by country, there exist a legal and an ethical foundation for resection, when indicated, in the United Staes. A recent meta-analysis on the management of incidental MDs revealed an overall positive shift toward resection in patients with high-risk factors[20]. We recommend surgical consent should either routinely discuss incidental diverticulectomy before performing appendectomy or consent be obtained from the patient’s medical decision maker while the patient is under anesthesia.

Our study had some limitations. First, this study was retrospective in nature, and the ACS-NSQIP database contained potential coding errors and unaccounted for covariates. Second, this study was limited to 30-day postoperative complications; long-term complications, including readmission and small bowel obstruction, were not analyzed. To further investigate the safety and rationale for the resection of incidental asymptomatic MDs during laparoscopic appendectomy, prospective multicenter randomized studies with long-term follow-up may be considered.

We present a 34 year-old woman who underwent incidental Meckel diverticulectomy without complications. Our analysis of the ACS-NSQIP database suggests that concomitant Meckel diverticulectomy during appendectomy does not significantly increase the rate of 30-day postoperative complications but results in longer operative times and hospital stays. Routine resection of incidental and asymptomatic MDs may not be necessary. Instead, decisions should be based on individual patient factors, including clinical presentation and MD characteristics.

We would like to thank Drs. Cassaundra K. Burt, Zachary D. Miller, Logan Peter, Austin Hingtgen, and Krystina Kalland for their assistance with this study.

| 1. | Żyluk A. Management of incidentally discovered unaffected Meckel's diverticulum - a review. Pol Przegl Chir. 2019;91:41-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Shimizu S, Hara H, Muto Y, Kido T, Miyata R, Itabashi M. Laparoscopic management of small bowel obstruction secondary to a mesodiverticular band of a Meckel's diverticulum in an adult: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103:e39164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Niasse A, Ndiaye A, Dieng PS, Dieng M, Ndong A, Cissé M, Dieng M, Konaté I. Meckel's diverticulum complicated by acute intestinal obstruction: a case report. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2024;86:4807-4810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lequet J, Menahem B, Alves A, Fohlen A, Mulliri A. Meckel's diverticulum in the adult. J Visc Surg. 2017;154:253-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lindeman RJ, Søreide K. The Many Faces of Meckel's Diverticulum: Update on Management in Incidental and Symptomatic Patients. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2020;22:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Park JJ, Wolff BG, Tollefson MK, Walsh EE, Larson DR. Meckel diverticulum: the Mayo Clinic experience with 1476 patients (1950-2002). Ann Surg. 2005;241:529-533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 347] [Cited by in RCA: 371] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lin XK, Huang XZ, Bao XZ, Zheng N, Xia QZ, Chen CD. Clinical characteristics of Meckel diverticulum in children: A retrospective review of a 15-year single-center experience. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e7760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Soltero MJ, Bill AH. The natural history of Meckel's Diverticulum and its relation to incidental removal. A study of 202 cases of diseased Meckel's Diverticulum found in King County, Washington, over a fifteen year period. Am J Surg. 1976;132:168-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 269] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dumper J, Mackenzie S, Mitchell P, Sutherland F, Quan ML, Mew D. Complications of Meckel's diverticula in adults. Can J Surg. 2006;49:353-357. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Moore T, Johnston AO. Complications of Meckel's diverticulum. Br J Surg. 1976;63:453-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Varcoe RL, Wong SW, Taylor CF, Newstead GL. Diverticulectomy is inadequate treatment for short Meckel's diverticulum with heterotopic mucosa. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74:869-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zani A, Eaton S, Rees CM, Pierro A. Incidentally detected Meckel diverticulum: to resect or not to resect? Ann Surg. 2008;247:276-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cullen JJ, Kelly KA, Moir CR, Hodge DO, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ 3rd. Surgical management of Meckel's diverticulum. An epidemiologic, population-based study. Ann Surg. 1994;220:564-8; discussion 568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jadlowiec CC, Bayron J, Marshall WT 3rd. Is an Incidental Meckel's Diverticulum Truly Benign? Case Rep Surg. 2015;2015:679097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Thirunavukarasu P, Sathaiah M, Sukumar S, Bartels CJ, Zeh H 3rd, Lee KK, Bartlett DL. Meckel's diverticulum--a high-risk region for malignancy in the ileum. Insights from a population-based epidemiological study and implications in surgical management. Ann Surg. 2011;253:223-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bani-Hani KE, Shatnawi NJ. Meckel's diverticulum: comparison of incidental and symptomatic cases. World J Surg. 2004;28:917-920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zulfikaroglu B, Ozalp N, Zulfikaroglu E, Ozmen MM, Tez M, Koc M. Is incidental Meckel's diverticulum resected safely? N Z Med J. 2008;121:39-44. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Robijn J, Sebrechts E, Miserez M. Management of incidentally found Meckel's diverticulum a new approach: resection based on a Risk Score. Acta Chir Belg. 2006;106:467-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Grimaldi L, Zingaro N, Trecca A. [Surgical management of incidental Meckel's diverticulum: the necessity to obtain the informed consent]. Minerva Chir. 2005;60:71-75. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Rahmat S, Sangle P, Sandhu O, Aftab Z, Khan S. Does an Incidental Meckel's Diverticulum Warrant Resection? Cureus. 2020;12:e10307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |