Published online Mar 27, 2024. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i3.823

Peer-review started: October 27, 2023

First decision: December 6, 2023

Revised: January 3, 2024

Accepted: February 25, 2024

Article in press: February 25, 2024

Published online: March 27, 2024

Processing time: 146 Days and 24 Hours

Abdominal wall deficiencies or weakness are a common complication of tem

To evaluate the effectiveness of using an RTM to reinforce the abdominal wall at stoma takedown sites.

Twenty-eight patients were selected with a parastomal and/or incisional hernia who had received a temporary ileostomy or colostomy for fecal diversion after rectal cancer treatment or trauma. Following hernia repair and proximal stoma closure, RTM (OviTex® 1S permanent or OviTex® LPR) was placed to reinforce the abdominal wall using a laparoscopic, robotic, or open surgical approach. Post-operative follow-up was performed at 1 month and 1 year. Hernia recurrence was determined by physical examination and, when necessary, via computed tomo

The observational study cohort included 16 male and 12 female patients with average age of 58.5 years ± 16.3 years and average body mass index of 26.2 kg/m2 ± 4.1 kg/m2. Patients presented with a parastomal hernia (75.0%), in

RTMs were used successfully to treat parastomal and incisional hernias at ileostomy reversal, with no hernia recurrences and favorable outcomes after 1-month and 1-year.

Core Tip: Reinforced tissue matrices (RTMs), which include elements of both synthetic and biologic mesh materials, were shown to be effective in treating parastomal and incisional hernia following ileostomy or colostomy reversal. Twenty-eight patients received OviTex® RTM to reinforce the abdominal wall using a laparoscopic, robotic, or open surgical approach. Positive primary outcomes (i.e., 0% hernia recurrence) and low rates of complications were observed at 1-month and 1-year follow-up.

- Citation: Lake SP, Deeken CR, Agarwal AK. Reinforced tissue matrix to strengthen the abdominal wall following reversal of temporary ostomies or to treat incisional hernias. World J Gastrointest Surg 2024; 16(3): 823-832

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v16/i3/823.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v16.i3.823

Hernias commonly develop at locations in the abdominal wall that have been weakened or breached in some way. Parastomal hernias often occur at sites where stomas have been placed through the abdomen, with incidence of hernia reported to be as high as 28% and 48% for colostomies and ileostomies, respectively[1,2]. Some researchers/clinicians have suggested that development of a parastomal hernia is inevitable in patients with stomas and that the variability in reported occurrence rates is due primarily to differences in duration (i.e., length of time post-stoma creation) and type

Incisional hernias can develop at temporary stoma locations after takedown of colostomies or ileostomies. Studies tracking hernia development following stoma closure have reported rates ranging between 15%-35%[11-13]. Significant risk factors include high body mass index (BMI), previous history of hernia, longer reversal time, open resection, hyper

Synthetic meshes have been used for many years to aid the repair of all types of hernia (e.g., ventral, incisional, pa

Biologic mesh has been used at the time of stomal closure to reinforce the abdominal wall. Several studies of patients that received biological mesh during stoma takedown demonstrated high feasibility, safe short-term results, and positive overall outcomes (e.g., low rates of incisional hernia and no surgical site infection)[12,15]. Results have compared fa

In an effort to take advantage of beneficial aspects of both synthetic and biologic materials for hernia repair, reinforced tissue matrices (RTMs) have been introduced and implemented clinically. RTMs contain a biologic scaffold composed of ovine forestomach matrix as the base material, which contains many natural components of native extracellular matrix and basement membrane, with a synthetic component (i.e., permanent or resorbable stitching throughout the scaffold) to provide additional strength and durability. Clinical outcomes using RTM materials in ventral hernia repair have been positive[18-21], suggesting that these materials can leverage advantages and limit disadvantages of both synthetic and biologic hernia meshes. In addition, favorable outcomes have been reported for the use of RTMs in treating inguinal and hiatal hernias[22,23]. To date, RTMs have not been reported in the published literature to reinforce the abdominal wall following stoma reversal. Given the positive results using RTMs in other hernia types, and the desire to reduce risk of hernia formation for high-risk patients following stomal removal, the objective of this study was to evaluate outcomes after implantation of RTMs to reinforce the abdominal wall at the time of stoma takedown to prevent hernia development and/or recurrence.

Patients were selected based on having previously received chemotherapy and/or radiation for rectal cancer with a temporary ileostomy or prior placement of a temporary ileostomy/colostomy after trauma. Exclusion criteria included any patient on Avastin, receiving palliative chemotherapy or radiation, classified as American Society of Anesthesiologists Grade 4, or otherwise unable to undergo surgery. This study was approved by the UT Health Houston Institutional Review Board. All patients provided consent to participate in the study.

Patients were placed in the supine position. Sequential compression devices were placed on extremities bilaterally, and general endotracheal anesthesia was administered. Pre-operative antibiotics were administered, namely 1 g cefazolin (Ancef; GlaxoSmithKline, Philadelphia, PA, United States) and 500 mg metronidazole (Flagyl; Pfizer, New York, NY, United States). The chest and abdomen were then prepped in the standard sterile manner. The proximal limb to the stoma was closed with 2-0 Vicryl® suture (Ethicon; Somerville, NJ, United States). Each patient was subjected to either a laparoscopic, robotic, or open surgical approach (described below).

Laparoscopic approach: A 5-mm stab incision was made in the left upper quadrant and the abdomen entered using a trocar with Optiview® technology (Ethicon). After insufflating the abdomen to 12 mmHg using carbon dioxide gas, the small bowel was reduced and any observed adhesions lysed. The underside of the stoma was completely mobilized from the hernia sac using a LigaSureTM hook (Medtronic; Minneapolis, MN, United States). The skin surrounding the stoma was incised with cautery approximately 2 mm away from the mucocutaneous interface. Subcutaneous tissues were dissected from the stoma with a combination of cautery and sharp dissection, while fascia and rectus were dissected sharply. Once the stoma was completely mobilized, the mesentery leading to the stoma was ligated and divided. The proximal and distal limb were divided and a side-to-side functional end-to-end anastomosis created with a single firing of a 60-mm Endo GIATM stapler (Medtronic). The common channel enterotomy was closed with a running 3-0 V-LocTM suture (Medtronic) and imbricated with seromuscular sutures. After placing a 3-0 Vicryl crotch stitch, 5 mL of indo

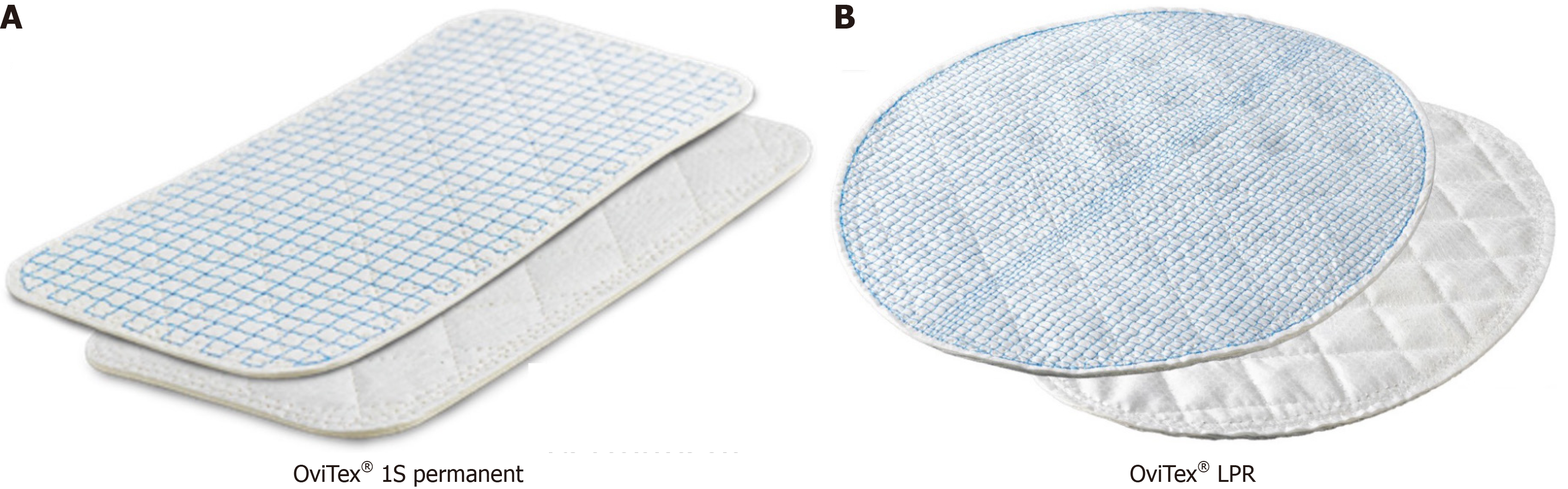

Robotic approach: Patients were placed in a slight reverse Trendelenburg position. Using an Optiview® trocar port, the abdomen was entered in the left upper quadrant and insufflated to 15 mmHg using carbon dioxide gas. An 8-mm port was placed in the left mid-lateral abdomen and another port placed in the left lower quadrant. After docking the robot, the peritoneum was dissected off the fascia superiorly and inferiorly. The hernia sac was reduced completely into the abdomen, and further dissection prepared the space for matrix placement. RTM (OviTex® 1S permanent or OviTex® LPR; Figure 1) was secured into the center of the abdominal cavity with 0 V-LocTM absorbable sutures, with attachments at the anterior abdominal wall, suture lines running superiorly and anteriorly, and sutures extending from the inferior and superior aspects cut at opposite ends. After desufflating the abdomen, ports were removed. Port incisions were irrigated and closed using 4-0 Monocryl® subcuticular closure. DermabondTM was used to cover the skin incisions, and most patients received a subcutaneous drain.

Open approach: Retrorectus space was created by incising the medial border of the rectus sheath and extending bilateral myocutaneous flaps. The posterior sheath was closed with running 0 Vicryl® suture. RTM (OviTex® 1S permanent; Figure 1A) was cut to size and secured in the retrorectus space from xiphoid to pubis with four PDSTM transfascial sutures (Ethicon). The hernia sac was resected and the anterior rectus fascia closed with PDSTM sutures. A 19Fr Jackson-Pratt® wound drain (Cardinal Health; Dublin, OH, United States) was placed in the subfascial retromuscular location, above the mesh, and secured to the skin with suture. The midline fascia was closed with PDSTM. DermabondTM was used to cover the skin incisions, and an abdominal binder was placed for 4 wk. In most patients, a subcutaneous drain was placed.

Post-operative follow-up was performed via in-person visits at 1 month and 1 year. The primary endpoint, hernia recurrence, was determined by physical examination; in cases of uncertainty, an anterior/posterior computed tomo

A total of 28 patients were enrolled (16 male; 12 female), with average age of 58.5 years ± 16.3 years and average BMI of 26.2 kg/m2 ± 4.1 kg/m2 (Table 1). Patients presented with a hernia at a former site of a temporary stoma (75%), incisional hernia (14.3%), or combined stoma-site/incisional hernia (10.7%). For this patient cohort, CDC wound classifications were class I (clean; 10.7%), class II (clean/contaminated; 7.1%), and class III (contaminated; 82.1%). Stomas were present in 78.6% of patients, and the most common co-morbidities were immunosuppression/steroid use (67.9%) and cancer (60.7%). Other details on patient conditions and co-morbidities are summarized in Table 1.

| Number of patients | n = 28 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 16 (57.1) |

| Female | 12 (42.9) |

| Age, yr | 58.5 ± 16.3 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.2 ± 4.1 |

| Patient type | |

| Stoma-site reinforcement | 21 (75.0) |

| Incisional | 4 (14.3) |

| Stoma-site/incisional | 3 (10.7) |

| CDC wound class | |

| Class I: Clean | 3 (10.7) |

| Class II: Clean/contaminated | 2 (7.1) |

| Class III: Contaminated | 23 (82.1) |

| Recurrent | 5 (17.9) |

| Prior hernia repairs | 5 (17.9) |

| Prior wound infection | 6 (21.4) |

| Transplant patient | 0 (0) |

| Stoma present | 22 (78.6) |

| Cancer | 17 (60.7) |

| Immunosuppression/steroid use | 19 (67.9) |

| Hypoalbuminemia (albumin < 3.7 g/dL) | 12 (42.9) |

| Diabetes | 10 (35.7) |

| COPD/chronic cough | 8 (28.6) |

| Smoking | 8 (28.6) |

| MRSA | 0 (0) |

For the 28 patients enrolled in this study, average defect dimensions were 7.5 cm ± 3.9 cm in length by 6.9 cm ± 3.4 cm in width, with average area of 63.8 cm2 ± 77.2 cm2 (Table 2). The most common surgical approach was laparoscopic (53.6%), followed by robotic (35.7%), and open (10.7%). When implanting the RTM (OviTex® LPR in 82.1% of cases, OviTex®1S in 17.9% of cases), the most common placement was sublay (82.1%), with an intraperitoneal onlay (IPOM; 17.9%) approach used less frequently. Matrices of various dimensions were used: 9 cm × 9 cm (71.4%), 10 cm × 12 cm (7.1%), 16 cm × 20 cm (14.3%), and 20 cm × 20 cm (7.1%). Component separation was achieved using a right myocutaneous flap in most cases (64.3%), with fewer cases using left myocutaneous flap (7.1%), bilateral flaps (7.1%), unspecified separation (3.6%), or no component separation (17.9%). Bowel anastomosis was present in 82.1% of patients. Drains were placed in subcutaneous (82.1%) and retromuscular (10.7%) positions in a total of 24 of 28 (85.7%) of patients. Across all patients, the average duration of surgery was 85.7 min ± 40.9 min.

| Value | |

| Surgical approach | |

| Open | 3 (10.7) |

| Laparoscopic | 15 (53.6) |

| Robotic | 10 (35.7) |

| Implant location | |

| Sublay | 23 (82.1) |

| IPOM | 5 (17.9) |

| Matrix | |

| OviTex 1S® | 5 (17.9) |

| OviTex LPR® | 23 (82.1) |

| Duration of surgery | 85.7 min ± 40.9 min |

| Defect dimensions | |

| Length | 7.5 cm ± 3.9 cm |

| Width | 6.9 cm ± 3.4 cm |

| Mesh dimensions (cm × cm) | |

| 9 × 9 | 20 (71.4) |

| 10 × 12 | 2 (7.1) |

| 16 × 20 | 4 (14.3) |

| 20 × 20 | 2 (7.1) |

| Component separation | |

| Left myocutaneous flap | 2 (7.1) |

| Right myocutaneous flap | 18 (64.3) |

| Bilateral | 2 (7.1) |

| Unspecified | 1 (3.6) |

| None | 5 (17.9) |

| Bowel anastomosis | 23 (82.1) |

| Intraoperative blood transfusion | 0 (0) |

| Concomitant procedure(s) | 0 (0) |

| Drains placed | |

| At least one | 24 (85.7) |

| None | 4 (14.3) |

| Drain locations | |

| Abdominal wall | 0 (0) |

| Subcutaneous | 23 (82.1) |

| Retromuscular | 3 (10.7) |

| Skin closure | 3 (10.7) |

| Vacuum-assisted closure device | 0 (0) |

All enrolled patients (n = 28) were evaluated at 1-month and 1-year follow-ups (Table 3). For the primary outcome, there were no hernia recurrences (0%) at either time point. The average hospital length of stay was 2.1 d ± 1.2 d and return to work occurred at 8.3 post-operative days ± 3.0 post-operative days. Three patients (10.7%) were readmitted before the 1-month follow-up due to mesh infection and/or gastrointestinal issues. There were no hospital readmissions between 1 month and 1 year. Of the measured secondary surgical outcomes (Table 3), fistula and mesh infection were observed in two patients each (7.1% of total group; one patient had both complications), leading to partial mesh removal in one patient (3.6% of total study population). The patient who received a partial mesh removal, which area was likely gra

| Item | 1 month | 1 yr |

| Number of patients | 28 | 28 |

| Primary endpoint | ||

| Hernia recurrence | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Secondary endpoints | ||

| Length of stay | 2.1 d ± 1.2 d | NA |

| Return to work | 8.3 d ± 3.0 d | NA |

| Readmission | 3 (10.7) | 0 (0) |

| Wound | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Mesh infection | 2 (7.1) | 0 (0) |

| Gastrointestinal | 2 (7.1) | 0 (0) |

| Surgical site infection | ||

| Superficial | 0 (0) | NA |

| Deep | 0 (0) | NA |

| Seroma | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Hematoma | 0 (0) | NA |

| Wound dehiscence | 0 (0) | NA |

| Fistula | 2 (7.1) | 0 (0) |

| Mechanical obstruction | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Mesh infection | 2 (7.1) | 0 (0) |

| Mesh removal | 1 (3.6) | 0 (0) |

In this study of 28 patients, the use of an RTM to treat incisional hernias and/or reinforce the abdominal wall following ileostomy or colostomy reversal led to successful results in terms of the primary endpoint of hernia recurrence, with no recurrences at 1 month or 1 year follow-up. In addition, although some secondary complications were observed at 1 month (e.g., fistula, mesh infection), all had resolved by the 1-year follow-up timepoint. Thus, overall outcomes were positive in augmenting parastomal and/or incisional hernia repair with RTM. Due to heterogeneity of the patient population, a range of surgical approaches, mesh types/sizes, implant locations, and component separation techniques were employed. Additionally, most of the repair procedures were in contaminated fields (82.1% CDC Class III) and many of the study participants were immunocompromised (67.9%) and/or had been diagnosed with cancer (60.7%), such that many of the procedures represented challenging clinical cases. Still, positive clinical results were achieved for all patients enrolled in this study by the study endpoint.

The primary novelty of this study was the use of RTM to repair incisional hernias and/or reinforce the abdominal wall after removal of temporary ostomies. The composite RTM materials used in the current study represent an approach that leverages the advantages of both biologic (e.g., better biocompatibility, reduced infection) and synthetic (e.g., enhanced mechanical strength) materials, which likely contributed to observed successful outcomes. The OviTex RTMs contain layers of ovine forestomach matrix scaffolds stitched together with permanent or resorbable polymer fibers (such as polypropylene or polyglycolic acid). For this study, OviTex® 1S permanent (6 layers) or OviTex® LPR scaffolds (4 layers) were used for repairs, with mesh selection being based more on defect size than on other differences between these two meshes (e.g., number of layers, stitching pattern, etc.). OviTex® LPR was used more following ostomy closure while Ovi

In addition to repairing hernias that are already present, previous studies have shown positive outcomes when using biologic mesh to reinforce the abdominal wall during stoma takedown[12,15], leading to reduced rates of subsequent in

This study is not without limitations. A total of 28 individuals were evaluated in this study, which is a larger patient population than many case studies, but still a relatively small sample size. In addition, the patient population was re

In conclusion, RTMs were used to successfully treat abdominal wall deficiencies or weakness and/or incisional hernias at the time of ileostomy or colostomy reversal, with positive primary outcomes (i.e., 0% recurrences) and low rates of com

Abdominal wall deficiencies are a common complication of temporary ostomies, and incisional hernias frequently develop after colostomy or ileostomy takedown. Synthetic and biologic meshes have been successfully leveraged to re

To determine if RTMs could be successfully used to strengthen the abdominal wall after removal of temporary co

To determine rates of primary (i.e., hernia recurrence) and secondary (i.e., length of hospital stay, time to return to work, hospital readmissions) outcomes after using RTM to reinforce the abdominal wall or repair an incisional hernia after removal of a temporary stoma.

Twenty-eight patients were selected with a parastomal and/or incisional hernia who had received a temporary ileostomy or colostomy. RTM was placed using a laparoscopic, robotic, or open surgical approach. Post-operative follow-up was performed at 1 month and 1 year.

At 1-month and 1-year follow-ups, there were no hernia recurrences (0%). Average hospital stays were 2.1 d ± 1.2 d and return to work occurred at 8.3 post-operative days ± 3.0 post-operative days. Three patients (10.7%) were readmitted before the 1-month follow up due to mesh infection and/or gastrointestinal issues. Fistula and mesh infection were ob

RTMs were used successfully to treat parastomal and incisional hernias at ileostomy reversal, with no hernia recurrences and favorable outcomes after 1-month and 1-year.

Future examination of larger and more heterogeneous patient populations, more standardized surgical techniques, and longer evaluation endpoints could further demonstrate the utility of this approach in limiting the negative impacts of hernias for patients with abdominal stomas.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ji ZL, China; Tsujinaka S, Japan S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xu ZH

| 1. | Carne PW, Robertson GM, Frizelle FA. Parastomal hernia. Br J Surg. 2003;90:784-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 453] [Cited by in RCA: 410] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fleshman JW, Beck DE, Hyman N, Wexner SD, Bauer J, George V; PRISM Study Group. A prospective, multicenter, randomized, controlled study of non-cross-linked porcine acellular dermal matrix fascial sublay for parastomal reinforcement in patients undergoing surgery for permanent abdominal wall ostomies. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:623-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ellis CN. Short-term outcomes with the use of bioprosthetics for the management of parastomal hernias. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:279-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Smart NJ, Velineni R, Khan D, Daniels IR. Parastomal hernia repair outcomes in relation to stoma site with diisocyanate cross-linked acellular porcine dermal collagen mesh. Hernia. 2011;15:433-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Aycock J, Fichera A, Colwell JC, Song DH. Parastomal hernia repair with acellular dermal matrix. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2007;34:521-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hammond TM, Huang A, Prosser K, Frye JN, Williams NS. Parastomal hernia prevention using a novel collagen implant: a randomised controlled phase 1 study. Hernia. 2008;12:475-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hufford T, Tremblay JF, Mustafa Sheikh MT, Marecik S, Park J, Zamfirova I, Kochar K. Local parastomal hernia repair with biological mesh is safe and effective. Am J Surg. 2018;215:88-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Miller BT, Krpata DM, Petro CC, Beffa LRA, Carbonell AM, Warren JA, Poulose BK, Tu C, Prabhu AS, Rosen MJ. Biologic vs Synthetic Mesh for Parastomal Hernia Repair: Post Hoc Analysis of a Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2022;235:401-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Taner T, Cima RR, Larson DW, Dozois EJ, Pemberton JH, Wolff BG. The use of human acellular dermal matrix for parastomal hernia repair in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a novel technique to repair fascial defects. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:349-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Raigani S, Criss CN, Petro CC, Prabhu AS, Novitsky YW, Rosen MJ. Single-center experience with parastomal hernia repair using retromuscular mesh placement. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:1673-1677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Amelung FJ, de Guerre LEVM, Consten ECJ, Kist JW, Verheijen PM, Broeders IAMJ, Draaisma WA. Incidence of and risk factors for stoma-site incisional herniation after reversal. BJS Open. 2018;2:128-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bhangu A, Futaba K, Patel A, Pinkney T, Morton D. Reinforcement of closure of stoma site using a biological mesh. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18:305-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Reinforcement of Closure of Stoma Site (ROCSS) Collaborative and West Midlands Research Collaborative. Prophylactic biological mesh reinforcement versus standard closure of stoma site (ROCSS): a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;395:417-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fazekas B, Fazekas B, Hendricks J, Smart N, Arulampalam T. The incidence of incisional hernias following ileostomy reversal in colorectal cancer patients treated with anterior resection. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2017;99:319-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lalezari S, Caparelli ML, Allamaneni S. Use of biologic mesh at ostomy takedown to prevent incisional hernia: A case series. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;41:107-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mäkäräinen EJ, Wiik HT, Kössi JA, Pinta TM, Mäntymäki LJ, Mattila AK, Kairaluoma MV, Ohtonen PP, Rautio TT. Synthetic mesh versus biological mesh to prevent incisional hernia after loop-ileostomy closure: a randomized feasibility trial. BMC Surg. 2023;23:68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lee JH, Ahn BK, Lee KH. Complications Following the Use of Biologic Mesh in Ileostomy Closure: A Retrospective, Comparative Study. Wound Manag Prev. 2020;66:16-22. [PubMed] |

| 18. | DeNoto G 3rd. Bridged repair of large ventral hernia defects using an ovine reinforced biologic: A case series. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022;75:103446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | DeNoto G 3rd, Ceppa EP, Pacella SJ, Sawyer M, Slayden G, Takata M, Tuma G, Yunis J. 24-Month results of the BRAVO study: A prospective, multi-center study evaluating the clinical outcomes of a ventral hernia cohort treated with OviTex® 1S permanent reinforced tissue matrix. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022;83:104745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | DeNoto G 3rd, Ceppa EP, Pacella SJ, Sawyer M, Slayden G, Takata M, Tuma G, Yunis J. A Prospective, Single Arm, Multi-Center Study Evaluating the Clinical Outcomes of Ventral Hernias Treated with OviTex(®) 1S Permanent Reinforced Tissue Matrix: The BRAVO Study 12-Month Analysis. J Clin Med. 2021;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Timmer AS, Claessen JJM, Brouwer de Koning IM, Haenen SM, Belt EJT, Bastiaansen AJNM, Verdaasdonk EGG, Wolffenbuttel CP, Schreurs WH, Draaisma WA, Boermeester MA. Clinical outcomes of open abdominal wall reconstruction with the use of a polypropylene reinforced tissue matrix: a multicenter retrospective study. Hernia. 2022;26:1241-1250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ferzoco S. Early experience outcome of a reinforced Bioscaffold in inguinal hernia repair: A case series. Int J Surg Open. 2018;12:9-11. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sawyer MAJ. New Ovine Polymer-Reinforced Bioscaffold in Hiatal Hernia Repair. JSLS. 2018;22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |