Published online Mar 27, 2024. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i3.670

Peer-review started: December 4, 2023

First decision: December 28, 2023

Revised: January 6, 2024

Accepted: February 4, 2024

Article in press: February 4, 2024

Published online: March 27, 2024

Processing time: 108 Days and 22 Hours

Although intracorporeal anastomosis (IA) for colon cancer requires longer operative time than extracorporeal anastomosis (EA), its short-term postoperative results, such as early recovery of bowel movement, have been reported to be equal or better. As IA requires opening the intestinal tract in the abdominal cavity under pneumoperitoneum, there are concerns about intraperitoneal bacterial infection and recurrence of peritoneal dissemination due to the spread of bacteria and tumor cells. However, intraperitoneal bacterial contamination and medium-term oncological outcomes have not been clarified.

To clarify the effects of bacterial and tumor cell contamination of the intra-abdominal cavity in IA.

Of 127 patients who underwent laparoscopic colon resection for colon cancer from April 2015 to December 2020, 75 underwent EA (EA group), and 52 underwent IA (IA group). After propensity score matching, the primary endpoint was 3-year disease-free survival rates, and secondary endpoints were 3-year overall survival rates, type of recurrence, surgical site infection (SSI) incidence, number of days on antibiotics, and postoperative biological responses.

Three-year disease-free survival rates did not significantly differ between the IA and EA groups (87.2% and 82.7%, respectively, P = 0.4473). The 3-year overall survival rates also did not significantly differ between the IA and EA groups (94.7% and 94.7%, respectively; P = 0.9891). There was no difference in the type of recurrence between the two groups. In addition, there were no significant differences in SSI incidence or the number of days on antibiotics; however, postoperative biological responses, such as the white blood cell count (10200 vs 8650/mm3, P = 0.0068), C-reactive protein (6.8 vs 4.5 mg/dL, P = 0.0011), and body temperature (37.7 vs 37.5 °C, P = 0.0079), were significantly higher in the IA group.

IA is an anastomotic technique that should be widely performed because its risk of intraperitoneal bacterial contamination and medium-term oncological outcomes are comparable to those of EA.

Core Tip: Since intracorporeal anastomosis (IA) for colon cancer is a technique in which the intestinal tract is opened in the abdominal cavity under pneumoperitoneum, there have been concerns about intraperitoneal bacterial infection and recurrent peritoneal dissemination due to the spread of bacteria and tumor cells. However, there have been few reports of the degree of bacterial contamination of the intraperitoneal cavity and the medium-term oncological outcomes. This study showed that the medium-term results of IA were comparable to those of conventional extracorporeal anastomosis and were not affected by the spread of bacteria or tumor cells.

- Citation: Kayano H, Mamuro N, Kamei Y, Ogimi T, Miyakita H, Nakagohri T, Koyanagi K, Mori M, Yamamoto S. Evaluation of bacterial contamination and medium-term oncological outcomes of intracorporeal anastomosis for colon cancer: A propensity score matching analysis. World J Gastrointest Surg 2024; 16(3): 670-680

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v16/i3/670.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v16.i3.670

For the surgical treatment of colorectal cancer, laparoscopic surgery, as a minimally invasive treatment method, has become one of the standard treatments based on the results of trials to confirm short- and long-term outcomes in comparisons of open surgery and laparoscopic surgery[1-4]. As a further development of minimally invasive treatment methods, robot-assisted surgery is now being performed for colon cancer as well as rectal cancer. On the other hand, in the anastomosis method for gastrointestinal reconstruction, the intracorporeal anastomosis (IA) method has been used since the dawn of laparoscopic surgery for gastric cancer, which is also a type of gastrointestinal cancer. However, although laparoscopic surgery was more rapidly adopted for colorectal cancer than for gastric cancer, the use of IA for colorectal cancer has not spread as fast as for gastric cancer. In the case of IA for colorectal cancer, a randomized, controlled trial reported early recovery of intestinal peristalsis and reduction of complications[5,6] in terms of short-term outcomes, and in a site-specific study of colon cancer, there were no differences in survival and recurrence-free survival rates between IA and extracorporeal anastomosis (EA) for right-sided colon cancer[7,8]. In addition, IA for left-sided colon cancer was reported to result in early recovery of intestinal peristalsis and a low complication rate[9,10]. Numerous reports have documented the benefits of IA. However, because IA involves opening the intestinal tract in the abdominal cavity under pneumoperitoneum, there are still some concerns about bacterial infection and the spread of tumor cells, and the number of facilities performing IA is limited. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to clarify the effects of bacterial and tumor cell contamination by comparing IA and EA methods, with the primary endpoint of 3-year disease-free survival (DFS) rate and secondary endpoints of 3-year overall survival (OS) rate, type of recurrence, surgical site infection (SSI) incidence rate, number of days on antibiotics, and postoperative biological responses.

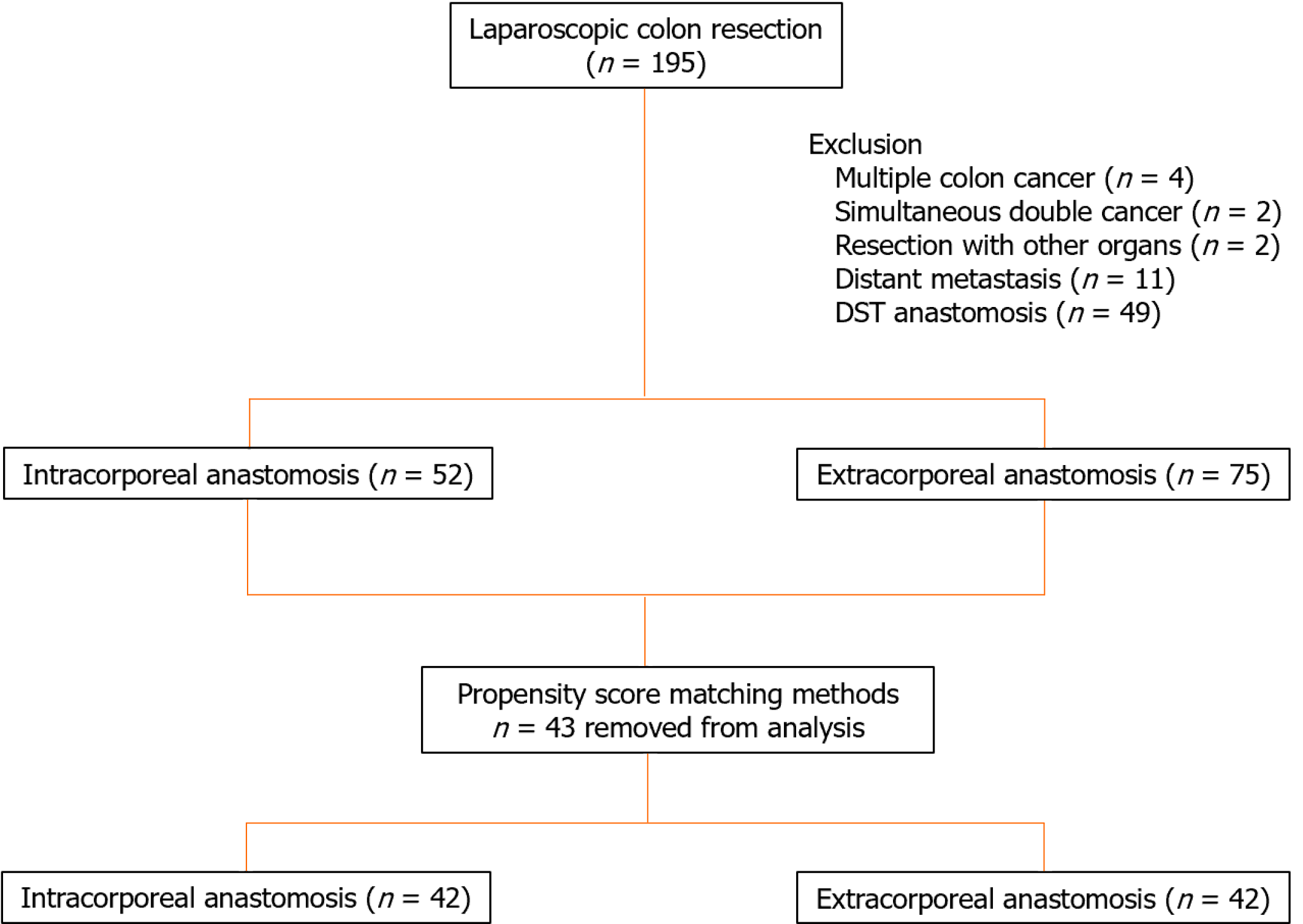

This retrospective, cohort study investigated 195 laparoscopic colon resections performed from April 2015 to December 2020 for colon cancer. Data for a total of 127 patients, 75 in the EA group and 52 in the IA group, who underwent laparoscopic colon resection for first colon cancer were analyzed after excluding 4 cases of multiple colon cancer, 2 cases of simultaneous double cancer, 2 cases of resection with other organs, 11 cases with distant metastasis, and 49 cases in which double-stapling technique anastomosis was performed (Figure 1). This study was designed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the Research Ethics Committee, Tokai University School of Medicine (23RC011), with a waiver of informed consent. The choice of IA or EA was left entirely to the surgeon.

Information on patient-related factors, surgery-related factors, tumor-related factors, surgical outcomes, and short- and medium-term postoperative outcomes is held in a database. Patient-related factors included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status (ASA-PS), Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), previous abdominal surgery, and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels. Surgery-related factors included bowel preparation, surgical procedure, and lymph node dissection area[11]. Tumor-related factors included tumor location, maximum tumor diameter, differentiation, histopathologic T stage, histopathologic N stage (American Joint Committee on Cancer/International Union for Cancer Control), lymphatic invasion, venous invasion, and perineural invasion, as well as TNM stage classification. Surgical outcomes included operative time, blood loss, conversion to open surgery, intraoperative complications, incision length, number of harvested lymph nodes, proximal margin, distal margin, and results of peritoneal fluid bacterial culture and cytology after peritoneal lavage with 3000 mL of saline solution after anastomosis. Bacterial culture and cytology of peritoneal lavage were performed in 73 patients (36 in the EA group and 37 in the IA group) who underwent surgery since April 2016. Short-term postoperative outcomes were times to first pass gas and first stool, time to resumption of oral intake, number of analgesics used, number of days on antibiotics, duration of postoperative hospitalization, time from surgery to adjuvant chemotherapy, completion of adjuvant chemotherapy, and duration of adjuvant chemotherapy. Postoperative complications were defined as total complications, SSI, and anastomotic leakage. Postoperative complications were classified according to the Clavien-Dindo (CD) classification[12]. The medium-term postoperative outcomes were defined as 3-year OS, 3-year DFS, and type of recurrence.

For EA, the intestinal tract was guided out of the body, and the oral and anal sides of the intestinal tract were separated by linear staplers. Then, a small hole was created on the transected side of the oral and anal intestinal tracts, and a linear stapler was inserted through the small holes to perform the anastomosis. The small hole was then closed with a linear stapler to create a functional end-to-end anastomosis. For IA, the oral and anal sides of the intestinal tract were separated by a linear stapler under laparoscopy. Small holes were made at a site 3 cm from the transected side of the oral intestinal tract and at a site 7 cm from the transected side of the anal intestine, and a stapler was inserted for lateral anastomosis with sequential peristalsis. The small hole was closed either by suture closure with a stapler or by suture closure with an A-L anastomosis using a 3-0 V-Loc (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, United States). Both anastomoses were performed using an ECHELON FLEXTM Powered ENDOPATH Stapler® 60 mm (blue cartridge) (Ethicon Endo-Surgery Inc., Cincinnati, OH, United States). Specimens were removed by extending the umbilical port wound.

In accordance with the colorectal cancer treatment guidelines prepared and published by the Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum, tumor markers were measured every 3 months, contrast-enhanced thoracoabdominal computed tomography (CT) was performed every 6 months, and the patients were examined. Positron emission tomography (PET)-CT was performed in all cases in which recurrence or metastasis was suspected on contrast-enhanced thoracoabdominal CT, and only when metastasis was diagnosed by PET-CT was the diagnosis confirmed as recurrence or metastasis. All imaging findings were diagnosed by a radiologist.

Propensity score matching was performed using a logistic regression model. One-to-one matching between the two groups was performed using the nearest neighbor matching method without replacement and with a caliper width of 0.2 standard deviations of the estimated propensity score logit. In the comparison between the two groups, the Mann-Whitney test was used for continuous variables, and the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test (for small sample sizes) was used for categorical variables, with P < 0.05 considered significant. OS and DFS were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method. Differences in survival curves were analyzed by the log-rank test. The index date for survival rate calculation was the date of surgery. The software used for this statistical analysis was JMP for Windows, version 13.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States).

The patient characteristics of each group before and after propensity score adjustment are shown in Table 1. Of the 127 patients analyzed, 52 were in the IA group, and 75 were in the EA group. There were significant differences between the IA and EA groups in surgical procedure (P = 0.0249) and extent of lymph node dissection (P = 0.0133). Propensity score matching was performed using surgical procedure, lymph node dissection area, and TNM stage classification as covariates. No differences between the two groups were observed after matching.

| Before propensity score matching | After propensity score matching | |||||

| IA (n = 52) | EA (n = 75) | P value | IA (n = 42) | EA (n = 42) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 69 (38-91) | 73 (38-92) | 0.1289 | 72 (38-91) | 73 (38-84) | 0.7438 |

| Sex | 0.4262 | 0.2751 | ||||

| Male | 24 (46.1) | 40 (53.3) | 19 (45.2) | 24 (57.1) | ||

| Female | 28 (53.8) | 35 (46.6) | 23 (54.7) | 18 (42.8) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.2 (17.7-28.3) | 22.8 (16.7-38.6) | 0.5964 | 22.3 (17.7-28.3) | 23.0 (16.7-30.2) | 0.8829 |

| ASA-PS | 0.2370 | 0.2808 | ||||

| I | 4 (7.6) | 7 (9.3) | 2 (4.7) | 5 (11.9) | ||

| II | 42 (80.7) | 51 (68.0) | 35 (83.3) | 29 (69.0) | ||

| III | 6 (11.5) | 17 (22.6) | 5 (11.9) | 8 (19.0) | ||

| CCI | 0.0703 | 0.2640 | ||||

| Low/medium | 35 (67.3) | 38 (50.6) | 28 (66.6) | 23 (54.7) | ||

| High | 17 (32.6) | 37 (49.3) | 14 (33.3) | 19 (45.2) | ||

| Previous abdominal operation | 0.8833 | 0.8114 | ||||

| Yes | 16 (30.7) | 24 (32.0) | 13 (30.9) | 12 (28.5) | ||

| No | 36 (69.2) | 51 (68.0) | 29 (69.0) | 30 (71.4) | ||

| CEA (ng/mL) | 3 (0.9-29.1) | 3.5 (0.9-89.8) | 0.1426 | 3.2 (1.0-29.1) | 3.5 (0.9-42.1) | 0.7807 |

| Bowel preparation | 0.7705 | 0.4154 | ||||

| MBP | 21 (40.3) | 35 (46.6) | 17 (40.4) | 23 (54.7) | ||

| OABP | 29 (55.7) | 37 (49.3) | 24 (57.1) | 18 (42.8) | ||

| None | 2 (3.8) | 3 (4.0) | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.3) | ||

| Surgical procedure | 0.0249 | 0.8546 | ||||

| Ileocecal resection | 19 (36.5) | 33 (44.0) | 19 (45.2) | 16 (38.1) | ||

| Right hemicolectomy | 12 (23.0) | 21 (28.0) | 12 (28.5) | 15 (35.7) | ||

| Left hemicolectomy | 7 (13.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Sigmoidectomy | 4 (7.6) | 8 (10.6) | 4 (9.5) | 5 (11.9) | ||

| Partial resection | 10 (19.2) | 13 (17.3) | 7 (16.6) | 6 (14.2) | ||

| Lymph node dissection area | 0.0133 | 1.0000 | ||||

| D2 | 2 (3.8) | 14 (18.6) | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.3) | ||

| D3 | 50 (96.1) | 61 (81.3) | 41 (97.6) | 43 (97.6) | ||

| Tumor location | 0.1940 | 0.7757 | ||||

| Right-sided | 38 (73.0) | 62 (82.6) | 34 (80.9) | 35 (83.3) | ||

| Left-sided | 14 (26.9) | 13 (17.3) | 8 (19.0) | 7 (16.6) | ||

| Tumor diameter (mm) | 31 (0-80) | 32 (0-110) | 0.1722 | 33 (0-80) | 30 (0-90) | 0.9928 |

| Differentiation | 0.6351 | 0.9745 | ||||

| G1 | 28 (53.8) | 38 (50.6) | 24 (57.1) | 23 (54.7) | ||

| G2 | 22 (42.3) | 31 (41.3) | 16 (38.1) | 17 (40.4) | ||

| G3 | 2 (3.8) | 6 (8.0) | 2 (4.7) | 2 (4.7) | ||

| T stage | 0.7605 | 0.8268 | ||||

| T1-2 | 25 (48.0) | 34 (45.3) | 20 (47.6) | 19 (45.2) | ||

| T3-4 | 27 (51.9) | 41 (54.6) | 23 (52.3) | 23 (54.7) | ||

| N stage | 0.4624 | 0.4834 | ||||

| N+ | 17 (32.6) | 20 (26.6) | 12 (28.5) | 15 (35.7) | ||

| N0 | 35 (67.3) | 55 (73.3) | 30 (71.4) | 27 (64.2) | ||

| Lymphatic invasion | 0.3614 | 0.2512 | ||||

| Yes | 32 (61.5) | 52 (69.3) | 25 (59.5) | 30 (71.4) | ||

| No | 20 (38.4) | 23 (30.6) | 17 (40.4) | 12 (28.5) | ||

| Venous invasion | 0.9346 | 0.4740 | ||||

| Yes | 17 (32.6) | 24 (32.0) | 11 (26.2) | 14 (33.3) | ||

| No | 35 (67.3) | 51 (68.0) | 31 (73.8) | 28 (66.6) | ||

| Perineural invasion | 0.8157 | 0.3927 | ||||

| Yes | 12 (23.0) | 16 (21.3) | 9 (21.4) | 6 (14.2) | ||

| No | 40 (76.9) | 59 (78.6) | 33 (78.5) | 36 (85.7) | ||

| TNM stage | 0.7146 | 0.8696 | ||||

| 0 | 3 (5.7) | 7 (9.3) | 3 (7.1) | 2 (4.7) | ||

| I | 18 (34.6) | 25 (33.3) | 15 (35.7) | 15 (35.7) | ||

| II | 14 (26.9) | 24 (32.0) | 12 (28.5) | 10 (23.8) | ||

| III | 17 (32.6) | 19 (25.3) | 12 (28.5) | 15 (35.7) | ||

There was no difference between the IA and EA groups in operative time, but the IA group had significantly less blood loss (14 vs 42 mL, P = 0.0087), shorter incision length (3 vs 4 cm, P = 0.0001), and longer distal margin length (100 vs 80 mm, P = 0.0071) than the EA group (Table 2). Bacterial culture and cytology of peritoneal lavage were performed for 39 patients in the IA group and 24 patients in the EA group. The results of bacterial culture of peritoneal lavage showed that the percentage of positive bacterial cultures was higher in the IA group, but the difference was not significant. Cytology results showed no difference between the two groups (Table 3).

| IA (n = 42) | EA (n = 42) | P value | |

| Operative time (min) | 228 (151-385) | 213 (121-406) | 0.1016 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 14 (3-312) | 42 (4-560) | 0.0087 |

| Conversion to open surgery | 0 (0) | 1 (2.3) | 0.3144 |

| Intraoperative complications | 0 (0) | 1 (2.3) | 0.3144 |

| Incision length (cm) | 3 (2-5) | 4 (3-7) | 0.0001 |

| Harvested lymph nodes | 22 (5-54) | 21 (2-60) | 0.8896 |

| Proximal margin (mm) | 80 (20-250) | 100 (35-260) | 0.2741 |

| Distal margin (mm) | 100 (40-190) | 80 (35-270) | 0.0071 |

| Time to first pass gas (d) | 1 (1-4) | 2 (1-5) | 0.0312 |

| Time to first stool (d) | 2 (1-6) | 3 (1-8) | 0.0484 |

| Time to resumption of oral intake (d) | 3 (2-31) | 3 (2-22) | 0.9151 |

| Number of analgesics used (count) | 3 (0-13) | 2 (0-16) | 0.1503 |

| Number of days on antibiotics (d) | 1 (1-40) | 1 (1-16) | 0.7283 |

| Duration of postoperative hospitalization (d) | 7 (7-44) | 9 (6-28) | 0.3200 |

| Total complications, n (%) | 0.3132 | ||

| CD Grade 1 | 2 (4.7) | 3 (7.1) | |

| CD Grade 2 | 5 (11.9) | 8 (19.0) | |

| CD Grade 3 | 5 (11.9) | 1 (2.3) | |

| Superficial/deep SSI | 3 (7.1) | 3 (7.1) | 1.0000 |

| Organ/space SSI | 4 (9.5) | 2 (4.7) | 0.3968 |

| Anastomotic leakage | 4 (9.5) | 2 (4.7) | 0.3968 |

| IA (n = 39) | EA (n = 24) | P value | |

| Bacterial culture | 0.4143 | ||

| Positive | 22 (56.4) | 11 (45.8) | |

| Negative | 17 (43.5) | 13 (54.1) | |

| Cytology | |||

| Class I | 13 (33.3) | 13 (54.1) | 0.1029 |

| Class II | 26 (66.6) | 11 (45.8) |

The IA group had a significantly faster time to first pass gas (1 vs 2 d, P = 0.0312) and time to first stool (2 vs 3 d, P = 0.0484) than the EA group. The number of days on antibiotics did not differ between the two groups. Postoperative complications, including total complications, superficial/deep SSI, organ/space SSI, and anastomotic leakage, did not differ between the two groups. Postoperative biological responses are shown in Table 4. On the first postoperative day, the WBC count (10200 vs 8650/mm3, P = 0.0068), C-reactive protein (6.8 vs 4.5 mg/dL, P = 0.0011), and body temperature (37.7 vs 37.5 °C, P = 0.0079) were all significantly higher in the IA group than in the EA group. No difference was observed between the two groups after the fourth and seventh days. There was no difference in the percentage of patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy between the two groups (33.3% vs 40.4%, P = 0.5634). Fourteen patients (33.3%) in the IA group and 17 patients (40.4%) in the EA group received adjuvant chemotherapy. No differences between the groups were observed for time from surgery to adjuvant chemotherapy and completion rate or duration of adjuvant chemotherapy (Table 5).

| IA (n = 42) | EA (n = 42) | P value | |

| WBC (count/mm3) | |||

| POD1 | 10200 (5600-21700) | 8650 (5200-14300) | 0.0068 |

| POD4 | 5550 (3100-11800) | 5500 (3600-13100) | 0.4851 |

| POD7 | 6250 (3200-13400) | 5200 (2800-11900) | 0.1157 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | |||

| POD1 | 6.8 (1.8-12.3) | 4.5 (0.9-12.1) | 0.0011 |

| POD4 | 6.2 (0.9-47.3) | 5.2 (0.8-23.8) | 0.2530 |

| POD7 | 1.8 (0.1-24.2) | 1.2 (0.2-8.0) | 0.2675 |

| Temperature (°C) | |||

| POD1 | 37.7 (36.9-39.9) | 37.5 (36.4-38.4) | 0.0079 |

| POD4 | 36.5 (35.3-38.8) | 36.4 (35.9-37.2) | 0.2835 |

| POD7 | 36.5 (35.3-38.8) | 36.4 (35.9-37.2) | 0.2835 |

| IA (n = 14) | EA (n = 17) | P value | |

| Time from surgery to adjuvant chemotherapy (d) | 28 (19-40) | 34 (20-48) | 0.4005 |

| Completion of adjuvant chemotherapy, n (%) | 12 (85.7) | 13 (76.4) | 0.5168 |

| Duration of adjuvant chemotherapy (d) | 179 (63-211) | 176 (88-231) | 0.5908 |

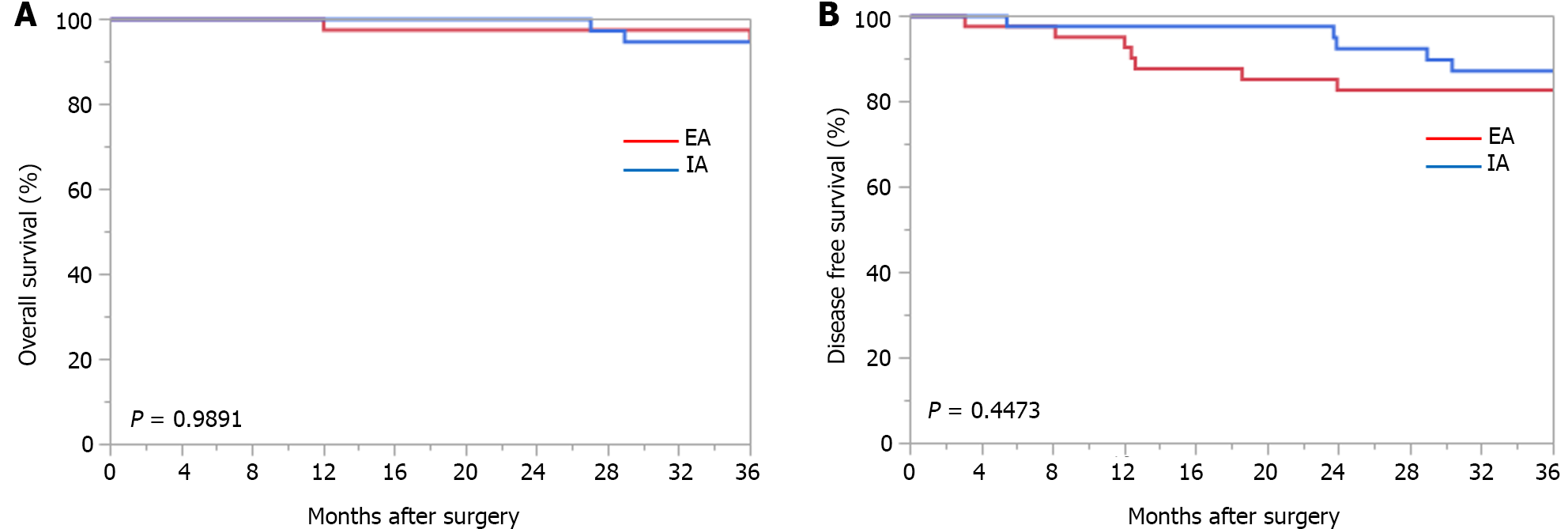

The medium-term outcomes are shown in Table 6. The median follow-up time was 31.9 months in the IA group and 36.7 months in the EA group. The 3-year OS and 3-year DFS periods for each anastomosis method are shown in Figure 2.

| IA (n = 42) | EA (n = 42) | P value | |

| Overall recurrence | 4 (9.5) | 6 (14.2) | 0.5004 |

| Hematogenous metastasis | 3 (7.1) | 4 (9.5) | 0.6930 |

| Lymphatic metastasis | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.3) | 1.0000 |

| Peritoneal metastasis | 0 (0) | 1 (2.3) | 0.3144 |

Three-year OS rates were not significantly different between the IA and EA groups (94.7% vs 94.7%, respectively; P = 0.9891). DFS at 3 years was also not significantly different between the IA and EA groups (87.2% vs 82.7%, respectively, P = 0.4473). There was no difference between the two groups in the type of recurrence.

Compared to EA, IA is somewhat more difficult to perform, and the technique of opening the intestinal tract in the abdominal cavity under insufflation may result in bacterial infection and dissemination of tumor cells; therefore, the number of facilities that have introduced IA is limited.

This retrospective study using propensity score matching was performed to examine the two biggest problems in IA for colon cancer with opening the intestinal tract under pneumoperitoneum: (1) Bacterial contamination by spreading stool juices; and (2) peritoneal dissemination by spreading cancer cells. In a comparative study after propensity score matching, there was no difference in operative time as a surgical outcome for IA compared to EA in the present study. Previous studies have not reported a reduction in operative time. Some reports indicate that IA and EA are comparable in terms of operative time[13], but in most reports, IA is longer than EA[14,15], and this applies to robotic surgery[16,17]. On the other hand, the amount of bleeding was significantly lower in IA. This means that, in EA, there is bleeding from the mesentery due to forced traction when the intestine is guided out of the body and unintentional bleeding when the mesentery is processed, whereas in IA, there is no forced traction on the mesentery, and the mesentery is processed by energy devices in a qualified manner, resulting in less bleeding. IA also shortened the length of the incision wound. However, the degree of wound pain remained the same. In the present study, it is assumed that both IA and EA were performed with an open umbilical port wound when removing the diseased intestinal tract, which did not result in a difference in the number of analgesic medications used. Currently, the Pfannenstiel incision is often used in IA to remove the diseased intestinal tract, and this incision causes less wound pain. This incision also results in fewer incisional hernias[18,19]. The number of lymph nodes dissected did not differ between IA and EA, but the length of the resected intestine on the anal side was long enough for IA. This indicates that IA is not inferior to EA as a surgical technique for lymph node dissection in cancer treatment because the same number of lymph nodes can be dissected. Furthermore, IA allows for adequate length of the distal resection margin and proper dissection of paracolic lymph nodes, which are prone to lymph node metastasis. In the transverse colon, descending colon, and sigmoid colon, it is difficult to guide the intestinal tract outside the body in EA, so the length of the resected intestinal tract on the anal side tends to be shorter. However, IA has the advantage that the intestinal tract can be separated while maintaining an appropriate distance from the tumor, and the anastomosis can be performed safely. Therefore, in cases involving the left side of the transverse colon to the sigmoid colon, IA may be superior from an oncological standpoint and in terms of the safety of the surgical procedure.

Short-term postoperative results have generally shown that IA is associated with faster recovery of postoperative bowel motility than EA, and the results of the present study were similar[20]. IA is a less invasive treatment with the advantages of less blood loss, shorter incision length, and earlier recovery of bowel motility compared to EA. In terms of postoperative complications, the incidences of anastomotic leakage and SSI did not differ significantly.

The first problem with IA is the degree of bacterial contamination in the abdominal cavity. In the present study, although the difference was not significant, the percentage of positive bacterial cultures was higher for IA than for EA, suggesting that IA has a higher risk for bacterial contamination and that great care should be taken in surgical procedures. Although it has been reported that IA results in lower levels of inflammatory mediators, which are endogenous substances that cause and maintain inflammatory responses in the body, compared to EA[21], as the present study showed, IA generally results in higher postoperative body temperature and blood inflammatory responses. However, there was no difference in organ/space SSIs such as intra-abdominal abscesses, and there was no difference in the number of days on antibiotics to treat infections, indicating that, though bacterial contamination was higher than with EA, no treatment was required. The second problem, the dispersal of cancer cells in the abdominal cavity, is discussed in terms of: (1) The presence of cancer cells in the anastomotic intestinal tract; and (2) the prognostic value of a positive cytological diagnosis. First, it has been previously reported that, in colon cancer, the presence of free cancer cells in the intestinal tract to be anastomosed is as high as 30%-50%[22,23]. It has also been reported that the positive rate is higher for open surgery than for laparoscopic surgery. However, it has been reported that free cancer cells were not observed in intestinal tracts longer than 10 cm[23], and if an appropriate length of intestinal tract is taken, it is safe to open the intestinal tract without free cancer cells when performing IA. The presence of free cancer cells may cause anastomotic recurrence and peritoneal dissemination, and IA, which ensures intestinal length compared to EA, may have an oncological advantage. Second, the 5-year survival rate is reported to be worse for patients with cytology-positive colorectal cancer than for patients with cytology-negative colorectal cancer[24,25], and peritoneal recurrence is the most common form of recurrence. In a study of gastric cancer patients, there were reports that the prognosis was better in cases with a high volume of intraperitoneal lavage than in cases with a normal volume of intraperitoneal lavage after radical resection[26], whereas there were also reports that there was no improvement at all[27,28], making it difficult to eliminate the effects of disseminated cancer cells by intraperitoneal lavage. In the present study, ascitic fluid cytology was negative in all cases, and there was no evidence of shedding of free cancer cells from the intestinal tract. In addition, the timing of chemotherapy initiation and completion rates were the same for IA and EA, and the recurrence rate and type of recurrence were the same for IA; thus, the technique of IA is comparable oncologically to that of EA and is not problematic. From the above, the advantages and disadvantages of IA in clinical practice shown in the present study are as follows. In terms of surgical outcomes, the advantages are reduced blood loss, shortened wound length, and the ability to resect anal side intestine while maintaining an accurate anal bowel distance from the tumor and to anastomose safely. The disadvantage, in terms of surgical outcomes, is a longer operative time. In the short-term postoperative results, the advantage is early recovery of postoperative bowel movements, and the disadvantage is an increased inflammatory response.

The limitations of this study are that it was a retrospective study, although propensity score matching was used in the statistical analysis; second, it was a single-center study with a small number of patients; and third, the follow-up period was short (3 years). To overcome these limitations, a multicenter, prospective, observational study should be conducted.

The short-term postoperative results of IA are comparable or superior to those of EA. The medium-term results were oncologically comparable to those of EA, and peritoneal recurrence, which is a concern, was also comparable. The ability to accurately obtain the appropriate length of the resected intestine may be an advantage of IA from an oncological point of view.

Because intracorporeal anastomosis (IA) involves opening the intestinal tract in the abdominal cavity under pneumoperitoneum, concerns about bacterial infection and the spread of tumor cells remain, and the number of institutions performing IA is limited.

The intraperitoneal bacterial contamination of the abdominal cavity by IA and the resulting perioperative biological reactions, as well as the medium-term oncological outcomes of IA, have not been clarified.

The purpose of this study was to clarify the effects of bacterial and tumor cell contamination of the abdominal cavity in IA.

Intracorporeal and extracorporeal anastomoses performed for colon cancer were compared after propensity score matching.

The 3-year disease-free survival rates did not significantly differ between the IA and extracorporeal anastomosis (EA) groups (87.2% vs 82.7%, respectively, P = 0.4473). The recurrence rate and type of recurrence also did not differ between the two groups. Furthermore, no significant differences were observed in the incidence of surgical site infection or the number of days on antibiotics, but the postoperative biological response was significantly higher in the IA group.

The IA method showed the same medium-term results as the conventional EA method; no obvious effects of bacterial or tumor cell dispersal were observed.

IA is not oncologically problematic and may be a less invasive anastomosis than EA.

The authors would like to thank Deputy Chief of Medical Clinic, Keitaro Tanaka, Otsu City Hospital, for advice on laparoscopic surgery techniques and study design; and Professor Yasuhiro Kanatani, Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Tokai University School of Medicine, for assistance with statistical analysis of the data.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Bordonaro M, United States; Zhang Z, China S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Cai YX

| 1. | Lacy AM, García-Valdecasas JC, Delgado S, Castells A, Taurá P, Piqué JM, Visa J. Laparoscopy-assisted colectomy versus open colectomy for treatment of non-metastatic colon cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:2224-2229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1901] [Cited by in RCA: 1816] [Article Influence: 79.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fleshman J, Sargent DJ, Green E, Anvari M, Stryker SJ, Beart RW Jr, Hellinger M, Flanagan R Jr, Peters W, Nelson H; Clinical Outcomes of Surgical Therapy Study Group. Laparoscopic colectomy for cancer is not inferior to open surgery based on 5-year data from the COST Study Group trial. Ann Surg. 2007;246:655-62; discussion 662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 789] [Cited by in RCA: 803] [Article Influence: 44.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Colon Cancer Laparoscopic or Open Resection Study Group; Buunen M, Veldkamp R, Hop WC, Kuhry E, Jeekel J, Haglind E, Påhlman L, Cuesta MA, Msika S, Morino M, Lacy A, Bonjer HJ. Survival after laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for colon cancer: long-term outcome of a randomised clinical trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:44-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 965] [Cited by in RCA: 1057] [Article Influence: 62.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jayne DG, Guillou PJ, Thorpe H, Quirke P, Copeland J, Smith AM, Heath RM, Brown JM; UK MRC CLASICC Trial Group. Randomized trial of laparoscopic-assisted resection of colorectal carcinoma: 3-year results of the UK MRC CLASICC Trial Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3061-3068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1108] [Cited by in RCA: 1113] [Article Influence: 61.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Allaix ME, Degiuli M, Bonino MA, Arezzo A, Mistrangelo M, Passera R, Morino M. Intracorporeal or Extracorporeal Ileocolic Anastomosis After Laparoscopic Right Colectomy: A Double-blinded Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Surg. 2019;270:762-767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 27.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bollo J, Turrado V, Rabal A, Carrillo E, Gich I, Martinez MC, Hernandez P, Targarona E. Randomized clinical trial of intracorporeal versus extracorporeal anastomosis in laparoscopic right colectomy (IEA trial). Br J Surg. 2020;107:364-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Hanna MH, Hwang GS, Phelan MJ, Bui TL, Carmichael JC, Mills SD, Stamos MJ, Pigazzi A. Laparoscopic right hemicolectomy: short- and long-term outcomes of intracorporeal versus extracorporeal anastomosis. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:3933-3942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Liao CK, Chern YJ, Lin YC, Hsu YJ, Chiang JM, Tsai WS, Hsieh PS, Hung HY, Yeh CY, You JF. Short- and medium-term outcomes of intracorporeal versus extracorporeal anastomosis in laparoscopic right colectomy: a propensity score-matched study. World J Surg Oncol. 2021;19:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Milone M, Angelini P, Berardi G, Burati M, Corcione F, Delrio P, Elmore U, Lemma M, Manigrasso M, Mellano A, Muratore A, Pace U, Rega D, Rosati R, Tartaglia E, De Palma GD. Intracorporeal versus extracorporeal anastomosis after laparoscopic left colectomy for splenic flexure cancer: results from a multi-institutional audit on 181 consecutive patients. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:3467-3473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Grieco M, Cassini D, Spoletini D, Soligo E, Grattarola E, Baldazzi G, Testa S, Carlini M. Intracorporeal Versus Extracorporeal Anastomosis for Laparoscopic Resection of the Splenic Flexure Colon Cancer: A Multicenter Propensity Score Analysis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2019;29:483-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. Japanese Classification of Colorectal, Appendiceal, and Anal Carcinoma: the 3d English Edition [Secondary Publication]. J Anus Rectum Colon. 2019;3:175-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 289] [Cited by in RCA: 436] [Article Influence: 72.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18532] [Cited by in RCA: 24849] [Article Influence: 1183.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chen F, Lv Z, Feng W, Xu Z, Miao Y, Zhang Y, Gao H, Zheng M, Zong Y, Zhao J, Lu A. Intracorporeal versus extracorporeal anastomosis in laparoscopic right colectomy: a retrospective study. World J Surg Oncol. 2023;21:154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Teramura K, Kitaguchi D, Matsuoka H, Hasegawa H, Ikeda K, Tsukada Y, Nishizawa Y, Ito M. Short-term outcomes following intracorporeal vs. extracorporeal anastomosis after laparoscopic right and left-sided colectomy: a propensity score-matched study. Int J Surg. 2023;109:2214-2219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ozawa H, Sakamoto J, Nakanishi H, Fujita S. Short-term outcomes of intracorporeal versus extracorporeal anastomosis after laparoscopic colectomy: a propensity score-matched cohort study from a single institution. Surg Today. 2022;52:616-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dohrn N, Yikilmaz H, Laursen M, Khesrawi F, Clausen FB, Sørensen F, Jakobsen HL, Brisling S, Lykke J, Eriksen JR, Klein MF, Gögenur I. Intracorporeal Versus Extracorporeal Anastomosis in Robotic Right Colectomy: A Multicenter, Triple-blind, Randomized Clinical Trial. Ann Surg. 2022;276:e294-e301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Squillaro AI, Kohn J, Weaver L, Yankovsky A, Milky G, Patel N, Kreaden US, Gaertner WB. Intracorporeal or extracorporeal anastomosis after minimally invasive right colectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol. 2023;27:1007-1016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Widmar M, Aggarwal P, Keskin M, Strombom PD, Patil S, Smith JJ, Nash GM, Garcia-Aguilar J. Intracorporeal Anastomoses in Minimally Invasive Right Colectomies Are Associated With Fewer Incisional Hernias and Shorter Length of Stay. Dis Colon Rectum. 2020;63:685-692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Selznick S, Levy J, Bogdan RM, Hawel J, Elnahas A, Alkhamesi NA, Schlachta CM. Laparoscopic right colectomies with intracorporeal compared to extracorporeal anastomotic techniques are associated with reduced post-operative incisional hernias. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:5500-5508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yao Q, Fu YY, Sun QN, Ren J, Wang LH, Wang DR. Comparison of intracorporeal and extracorporeal anastomosis in left hemicolectomy: updated meta-analysis of retrospective control trials. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149:14341-14351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Milone M, Desiderio A, Velotti N, Manigrasso M, Vertaldi S, Bracale U, D'Ambra M, Servillo G, De Simone G, De Palma FDE, Perruolo G, Raciti GA, Miele C, Beguinot F, De Palma GD. Surgical stress and metabolic response after totally laparoscopic right colectomy. Sci Rep. 2021;11:9652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hasegawa J, Nishimura J, Yamamoto S, Yoshida Y, Iwase K, Kawano K, Nezu R. Exfoliated malignant cells at the anastomosis site in colon cancer surgery: the impact of surgical bowel occlusion and intraluminal cleaning. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26:875-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kobayashi S, Inoue Y, Fujita F, Ito S, Yamaguchi I, Nakayama M, Kanetaka K, Takatsuki M, Eguchi S. Extent of intraluminal exfoliated malignant cells during surgery for colon cancer: Differences in cell abundance ratio between laparoscopic and open surgery. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2019;12:145-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sato K, Imaizumi K, Kasajima H, Kurushima M, Umehara M, Tsuruga Y, Yamana D, Obuchi K, Sato A, Nakanishi K. Comparison of prognostic impact between positive intraoperative peritoneal and lavage cytologies in colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2021;26:1272-1284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Matsui S, Fukunaga Y, Sugiyama Y, Iwagami M, Nagasaki T, Akiyoshi T, Konishi T, Kawachi H. Incidence and Prognostic Value of Lavage Cytology in Colorectal Cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022;65:894-900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Guo J, Xu A, Sun X, Zhao X, Xia Y, Rao H, Zhang Y, Zhang R, Chen L, Zhang T, Li G, Xu H, Xu D. Combined Surgery and Extensive Intraoperative Peritoneal Lavage vs Surgery Alone for Treatment of Locally Advanced Gastric Cancer: The SEIPLUS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:610-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Yang HK, Ji J, Han SU, Terashima M, Li G, Kim HH, Law S, Shabbir A, Song KY, Hyung WJ, Kosai NR, Kono K, Misawa K, Yabusaki H, Kinoshita T, Lau PC, Kim YW, Rao JR, Ng E, Yamada T, Yoshida K, Park DJ, Tai BC, So JBY; EXPEL study group. Extensive peritoneal lavage with saline after curative gastrectomy for gastric cancer (EXPEL): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6:120-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Misawa K, Mochizuki Y, Sakai M, Teramoto H, Morimoto D, Nakayama H, Tanaka N, Matsui T, Ito Y, Ito S, Tanaka K, Uemura K, Morita S, Kodera Y; Chubu Clinical Oncology Group. Randomized clinical trial of extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage versus standard treatment for resectable advanced gastric cancer (CCOG 1102 trial). Br J Surg. 2019;106:1602-1610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |