Published online Feb 27, 2024. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i2.585

Peer-review started: November 2, 2023

First decision: November 30, 2023

Revised: December 26, 2023

Accepted: January 29, 2024

Article in press: January 29, 2024

Published online: February 27, 2024

Processing time: 115 Days and 0.3 Hours

In recent years, the association between oral health and the risk of gastric cancer (GC) has gradually attracted increased interest. However, in terms of GC incidence, the association between oral health and GC incidence remains controversial. Periodontitis is reported to increase the risk of GC. However, some studies have shown that periodontitis has no effect on the risk of GC. Therefore, the present study aimed to assess whether there is a relationship between oral health and the risk of GC.

To assess whether there was a relationship between oral health and the risk of GC.

Five databases were searched to find eligible studies from inception to April 10, 2023. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale score was used to assess the quality of included studies. The quality of cohort studies and case-control studies were evaluated separately in this study. Incidence of GC were described by odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Funnel plot was used to represent the publication bias of included studies. We performed the data analysis by StataSE 16.

A total of 1431677 patients from twelve included studies were enrolled for data analysis in this study. According to our analysis, we found that the poor oral health was associated with higher risk of GC (OR = 1.15, 95%CI: 1.02-1.29; I2 = 59.47%, P = 0.00 < 0.01). Moreover, after subgroup analysis, the outcomes showed that whether tooth loss (OR = 1.12, 95%CI: 0.94-1.29; I2 = 6.01%, P > 0.01), gingivitis (OR = 1.19, 95%CI: 0.71-1.67; I2 = 0.00%, P > 0.01), dentures (OR = 1.27, 95%CI: 0.63-1.19; I2 = 68.79%, P > 0.01), or tooth brushing (OR = 1.25, 95%CI: 0.78-1.71; I2 = 88.87%, P > 0.01) had no influence on the risk of GC. However, patients with periodontitis (OR = 1.13, 95%CI: 1.04-1.23; I2 = 0.00%, P < 0.01) had a higher risk of GC.

Patients with poor oral health, especially periodontitis, had a higher risk of GC. Patients should be concerned about their oral health. Improving oral health might reduce the risk of GC.

Core Tip: The aim of this current study was to assess whether there was a relationship between oral health and the risk of gastric cancer (GC). A total of 1431677 patients from twelve included studies were enrolled for data analysis in this study. This article summarised all the papers over the years on the relationship between oral health and the incidence of GC. After analysing them, the existing controversies were resolved to some extent. It was useful to guide clinical work.

- Citation: Liu F, Tang SJ, Li ZW, Liu XR, Lv Q, Zhang W, Peng D. Poor oral health was associated with higher risk of gastric cancer: Evidence from 1431677 participants. World J Gastrointest Surg 2024; 16(2): 585-595

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v16/i2/585.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v16.i2.585

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the most common tumours worldwide and the forth leading cause of cancer death[1-3]. The incidence and mortality of GC continue to increase, and there are approximately 1 million new cases worldwide each year[3-5]. In China, more than 400000 new cases are diagnosed each year, accounting for 50% of new cases worldwide[6-8]. Prevention of GC has become a focal point because of these worrisome numbers. Prevention of GC can be divided into primary prevention (reducing the incidence of GC) and secondary prevention (early detection and treatment). Primary prevention includes smoking cessation, reducing salt intake, increasing fruit and vegetable intake, and other health behaviours, such as oral health behaviours[9].

The oral cavity is the conduit between the external environment and the gastrointestinal tract and is involved in the intake and digestion of food. Oral hygiene plays an important role in human health. Measures of oral health included tooth loss, periodontitis, gingivitis, dentures, and tooth brushing. Poor oral health has been shown to be a risk factor for many diseases, including cardiovascular disease, atherosclerosis, oral cancer, kidney cancer, lung cancer, oesophageal cancer, and pancreatic cancer[10-18].

In recent years, the association between oral health and the risk of GC has gradually attracted increased interest. However, in terms of GC incidence, the association between oral health and GC incidence remains controversial. Periodontitis is reported to increase the risk of GC[19]. However, some studies have shown that periodontitis has no effect on the risk of GC[20,21]. Therefore, the present study aimed to assess whether there is a relationship between oral health and the risk of GC.

Our study was produced in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement[22].

The PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, and Ovid databases were searched from inception to April 10, 2023. The two keywords used were oral health and GC. For oral health, the search strategy was as follows: “dental” OR “oral” OR “oral health” OR “oral hygiene behaviour” OR “oral hygiene” OR “oral behaviour” OR “tooth loss” OR “tooth missing” OR “dental caries” OR “full teeth” OR “salivary flow” OR “probing depth” OR “periodontal disease” OR “periodontitis” OR “gingivitis” OR “dentures” OR “tooth brushing”. In terms of GC, “gastric cancer” OR “gastric carcinoma” OR “gastric neoplasms” OR “stomach cancer” OR “stomach carcinoma” OR “stomach neoplasms” were searched. Then, we used “AND” to combine the two keywords. The language was limited to English.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were established to find eligible studies. The inclusion criteria for patients were as follows: (1) Patients were reported to have oral health problems; and (2) The incidence of GC was reported. The exclusion criteria for patients were as follows: (1) Had case reports, comments, letters to the editor, or conference abstracts; (2) Had data repeated or overlapped; and (3) Incomplete information.

The database search was independently conducted by two authors. The steps for screening eligible studies were as follows: (1) Excluded duplicate studies; (2) Scanned the titles and abstracts; and (3) Read the full text, including the reference. All disagreements were settled by group discussion.

The baseline characteristics of the individuals included in the studies and the incidence of GC were collected for data analysis in the present study. The baseline information of the enrolled studies included author, publication year, pub

The quality of the included studies was evaluated by the NOS score[23]. According to the NOS score, we divided studies into high quality (9 points), median quality (7-8 points), and low quality (< 7 points) groups. We evaluated the quality of the cohort studies and case-control studies separately in this study.

We defaulted the risk ratio (RR) and hazard ratio (HR) of GC reported in the included studies to be equivalent to the odds ratio (OR)[24]. The incidence of GC was described by the OR and 95% confidence interval (CI). I2 values and χ2 tests were used to assess the statistical heterogeneity[25,26]. The random effects DerSimonian-Laird model was used only. When a random effects model was used, P < 0.01 was considered to indicate statistical significance. StataSE 16 was used for the data analysis.

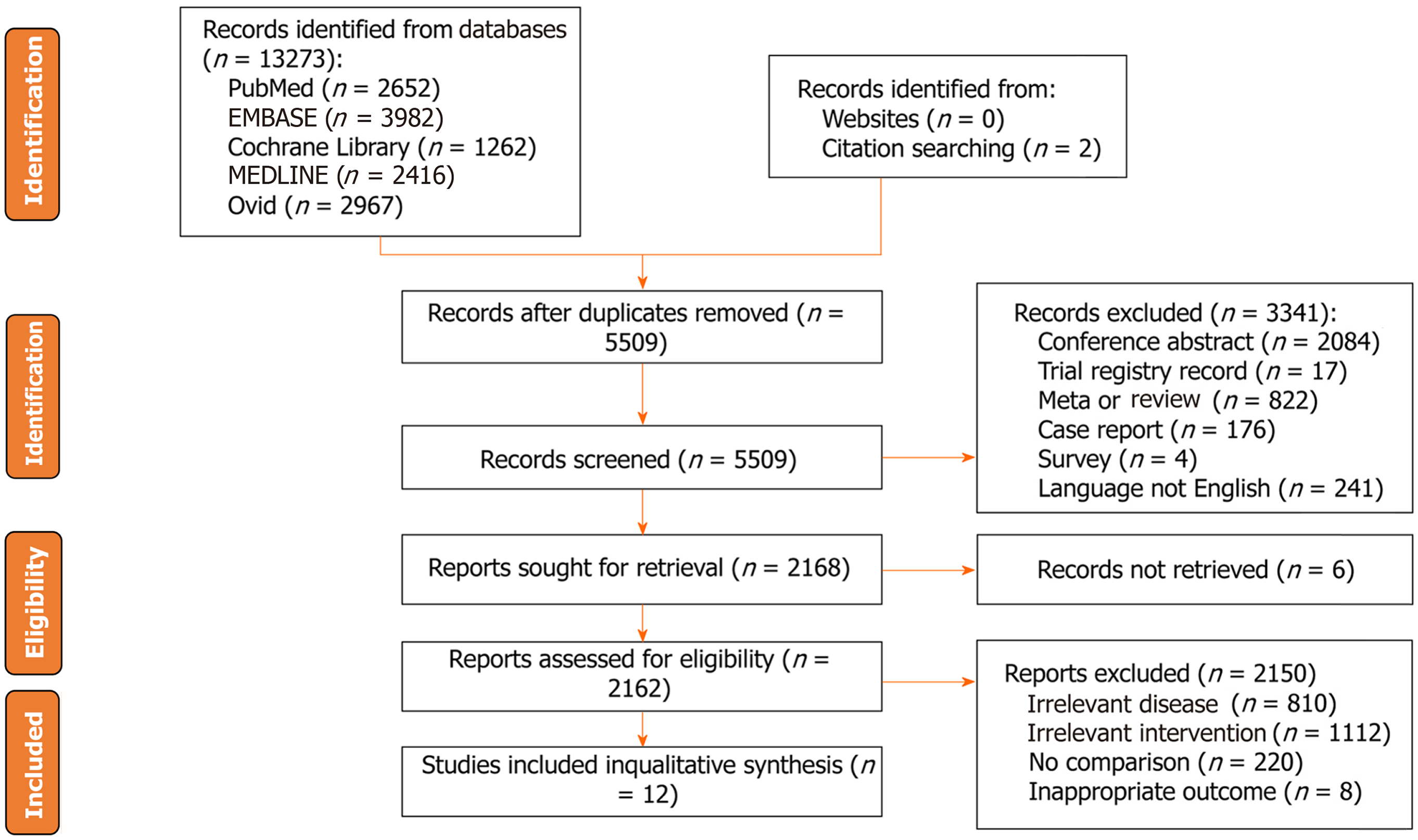

A total of 13279 studies were identified from five databases (2652 in PubMed, 3982 in EMBASE, 1262 in the Cochrane Library, 2416 in MEDLINE, 2967 in Ovid, and two from the citation searching) from inception to April 10, 2023. After duplicate removal, 5509 records remained. Three thousand forty-one unqualified studies were excluded according to the exclusion criteria. After excluding unqualified studies, 2168 studies were needed for eligibility, and six records were not retrieved. Finally, twelve eligible studies were included in this study[8,19-21,27-34] (Figure 1).

Twelve studies involving 1431677 patients were included in this study. The publication years ranged from 1998 to 2022. The published countries were mainly in China, Japan, United States, and Iran. The study period ranged from 1973 to 2011. There were nine cohort studies and three case-control studies. There were nine studies reporting tooth loss, three studies reporting periodontitis, two studies reporting gingivitis, three studies reporting dentures, and five studies reporting tooth brushing. More details of the included studies’ baseline characteristics, including the author, the number of patients, the follow-up period, the diagnosis of GC, and the NOS score, are shown in Table 1.

| Ref. | Country | Study date | Patients | Study type | Follow-up | Diagnosis of gastric cancer | Definition of oral health | NOS |

| Watabe et al[32], 1998 | Japan | October 1996 to September 1997 | 242 | Retrospective cohort study | NA | Gastric cancer | Brush teeth, decayed teeth, gingivitis, bad occlusion, dentures (partial and full), and lack of teeth ≥ 10 | 6 |

| Abnet et al[27], 2001 | China | March 1986 to May 1991 | 28868 | Prospective cohort study | 5.25 yr | Gastric cardia tumor and non-cardia tumor | Tooth loss | 8 |

| Hujoel et al[20], 2003 | United States | 1971 to 1992 | 11328 | Prospective cohort study | Until 1992 | Gastric cancer (ICD-9 151.0-151.9) | Periodontitis, gingivitis, and edentulism | 7 |

| Abnet et al[28], 2005 | Finland | 1985 to 1999 | 29124 | Prospective cohort study | April 1993 to April 1999 | Gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma | Tooth loss included 0-10 teeth lost, 11-31 teeth lost, and edentulous | 8 |

| Michaud et al[29], 2008 | United States | 1986 to January 2004 | 49375 | Prospective cohort study | Median of 17.7 yr | Gastric cancer | Periodontal disease and tooth loss | 9 |

| Hiraki et al[19], 2008 | Japan | 2000 to 2005 | 15720 | Case-control study | NA | Gastric cancer (ICD-10 C16) | Remaining teeth | 7 |

| Shakeri et al[31], 2013 | Iran | January 2004 to June 2008 | 922 | Case-control study | December 2004 to December 2011 | Gastric adenocarcinoma included non-cardia, cardia, and mixed-locations | Tooth loss, decayed, missing, filled teeth score, and frequency of tooth brushing | 6 |

| Ndegwa et al[30], 2018 | Sweden | 1973 to 1974 | 19831 | Prospective cohort study | 569233 person-years | Gastric cancer was divided into cardia (ICD 151.1) and non-cardia gastric cancer (all ICD-7 151 codes except ICD 151.1) | Number of teeth, dental plaque status, and presence of any oral mucosal lesions | 7 |

| Yano et al[33], 2021 | Iran | January 2004 to June 2008 | 50045 | Prospective cohort study | Until December 31, 2019 | Gastric cancer cases were limited to adenocarcinomas (cardia and non-cardia) | Frequency of tooth brushing, tooth loss, and the sum of decayed, missing, or filled teeth | 9 |

| Zhang et al[8], 2022 | China | October 2010 to September 2013 | 2873 | Case-control | NA | Gastric cancer was divided into esophagogastric junction cancer and total gastric cancer | Tooth loss after 20 yr, number of tooth loss after age 20 yr, age of first tooth loss after age 20 yr, denture wearing, number of filled teeth, missing and filled teeth, frequency of toothbrushing, frequency of oral discomfort while eating, avoidance of some foods because of oral problems | 6 |

| Zhang et al[34], 2022 | China | 2004 to 2008 | 510148 | Prospective cohort study | Median of 9.17 yr and range of 0.1 to 11.5 yr | Gastric cancer (ICD-10 C16) | Gum bleeding and rarely or never brush teeth | 9 |

| Kim et al[21], 2022 | South Korea | January 2003 to December 2015 | 713201 | Retrospective cohort study | Up to 10 yr | Gastric cancer (ICD-10 C16) | Periodontitis (who visited a dental clinic two or more than two times within one year and were diagnosed with periodontitis under those ICD-10 codes (K05.2, K05.3, K05.4, K05.5, and K05.6) | 9 |

Tables 2 and 3 show the results of the quality assessment by the NOS score for cohort studies and case-control studies, respectively. For cohort studies, three studies were graded as high quality (nine points), five studies were graded as median quality (seven to eight points), and one study was graded as low quality (six points). For case-control studies, one study was graded as high quality (nine points), and two studies were graded as low quality (six points). The details of the quality assessment are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

| Ref. | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Scores | |||||

| Representativeness of exposure | Selection of the non-exposure | Ascertainment of exposure | Demonstration that outcome was not present at start | Cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis | Assessment | Long follow-up for outcomes to occur | Adequacy of follow-up | ||

| Abnet et al[28], 2005 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ☆ | ★ | ★ | 8 |

| Abnet et al[27], 2001 | ☆ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 8 |

| Hiraki et al[19], 2008 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ☆ | ☆ | 7 |

| Hujoel et al[20], 2003 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ☆ | ☆ | 7 |

| Kim et al[21], 2022 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 9 |

| Michaud et al[29], 2008 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 9 |

| Ndegwa et al[30], 2018 | ☆ | ☆ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 7 |

| Watabe et al[32], 1998 | ☆ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 |

| Yano et al[33], 2021 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 9 |

| Ref. | Selection | Comparability | Exposure | Scores | |||||

| Adequate definition of cases | Representativeness of the cases | Selection of controls | Definition of controls | Control for important factor1 | Ascertainment of exposure | Same method of ascertainment for cases and controls | Non-response rate | ||

| Shakeri et al[31], 2013 | ★ | ☆ | ☆ | ★ | ★★ | ☆ | ★ | ★ | 6 |

| Zhang et al[8], 2022 | ★ | ☆ | ☆ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ☆ | 6 |

| Zhang et al[34], 2022 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 9 |

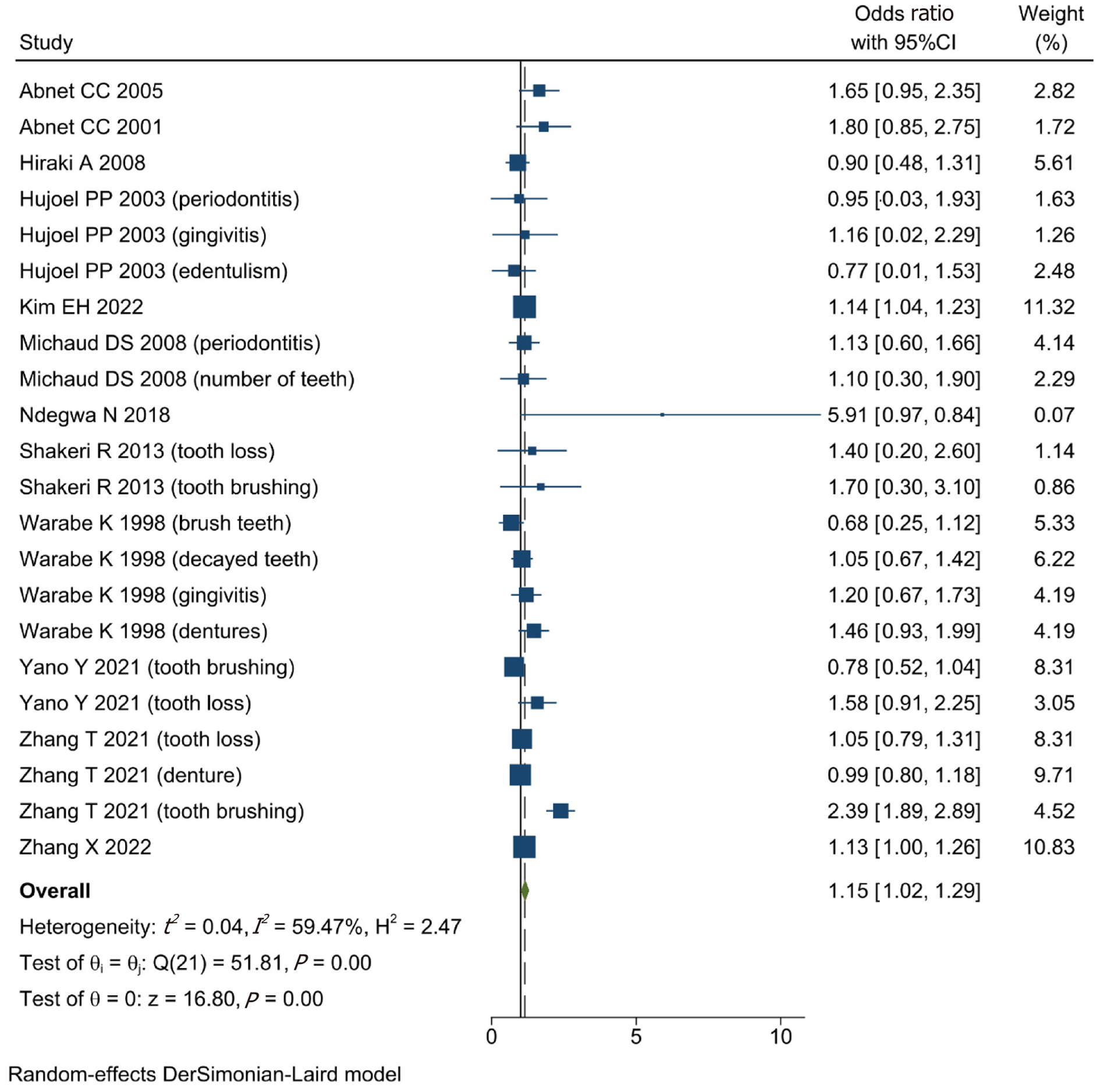

Before the data analysis, we adjusted the RR or HR to the OR. The information on the participants’ adjustment is shown in Table 4. According to the data analysis, poor oral health could increase the risk of GC (OR = 1.15, 95%CI: 1.02-1.29; I2 = 59.47%, P = 0.00 < 0.01) (Figure 2).

| Ref. | Variables of adjustment |

| Abnet et al[28], 2005 | Age and education |

| Abnet et al[27], 2001 | Age, sex, tobacco use, and alcohol use |

| Hiraki et al[19], 2008 | Age, sex, smoking and drinking status (never, former, current), vegetable and fruit intake, BMI, and regular exercise |

| Hujoel et al[20], 2003 | Age and gender |

| Kim et al[21], 2022 | Age |

| Michaud et al[29], 2008 | Age (continuous), ethnic origin (white, Asian, black), physical activity (quintiles), history of diabetes (yes or no), alcohol (quartiles), BMI (< 22, 22-24.9, 25-29.9, 30 +), geographical location (south, west, northeast, mid-west), height (quintiles), calcium intake (quintiles), total calorific intake (quintiles), red-meat intake (quintiles), fruit and vegetable intake (quintiles), vitamin D score (deciles), smoking history (never, past quit ≤ 10 yr, past quit > 10 yr, current 1-14 cigarettes per day, 15-24 cigarettes per day, 25 + cigarettes per day), and pack-years (continuous) |

| Ndegwa et al[30], 2018 | Age as time-scale, age at entry, sex, area of residence (rural, small-town or urban), tobacco use status (non-tobacco use, smoking only, snus only or mixed usage), and alcohol consumption (less than once a week versus once a week or more) |

| Shakeri et al[31], 2013 | Age, ethnicity, education, fruit and vegetable use, socioeconomic status, ever opium or tobacco use, and denture use |

| Watabe et al[32], 1998 | NA |

| Yano et al[33], 2021 | Age, sex, socioeconomic score, ethnicity, residence, education, cigarette use, and opium use |

| Zhang et al[8], 2022 | Age (continuous), sex, education (illiteracy, primary school, junior school, high school and above), marital status (single, married, divorced or widowed), job type (farmer, worker, others), wealth score (five levels), BMI 10 years ago (< 18.5 kg/m2, 1.85 to 24.0 kg/m2, 24.0 to 28.0 kg/m2, ≥ 28.0 kg/m2), tobacco smoking (never, ≤ 30 pack-years, > 30 pack-years), alcohol drinking (never, ≤ 80 g/d, > 80 g/d), H. pylori seropositivity (yes/no), and family history of GC (yes/no) |

| Zhang et al[34], 2022 | Age (continuous), sex (male, female), BMI (continuous), study sites (10 sites), education level (no formal school, primary or middle school, high school and above), marital status (married, other), household income per year (< 10000, < 10000-19999, < 20000-34999, or < 35000), alcohol consumption (non-drinker, occasional drinker, former drinker, or regular drinker), smoking status (never smoker, occasional smoker, former smoker, or regular smoker), physical activity in MET hours a day (continuous), aspirin prescription for CVD (no, yes, or missing), menopausal status (pre-menopausal or post-menopausal, women only), personal history of diabetes (no, yes), and family history of cancer (no, yes) |

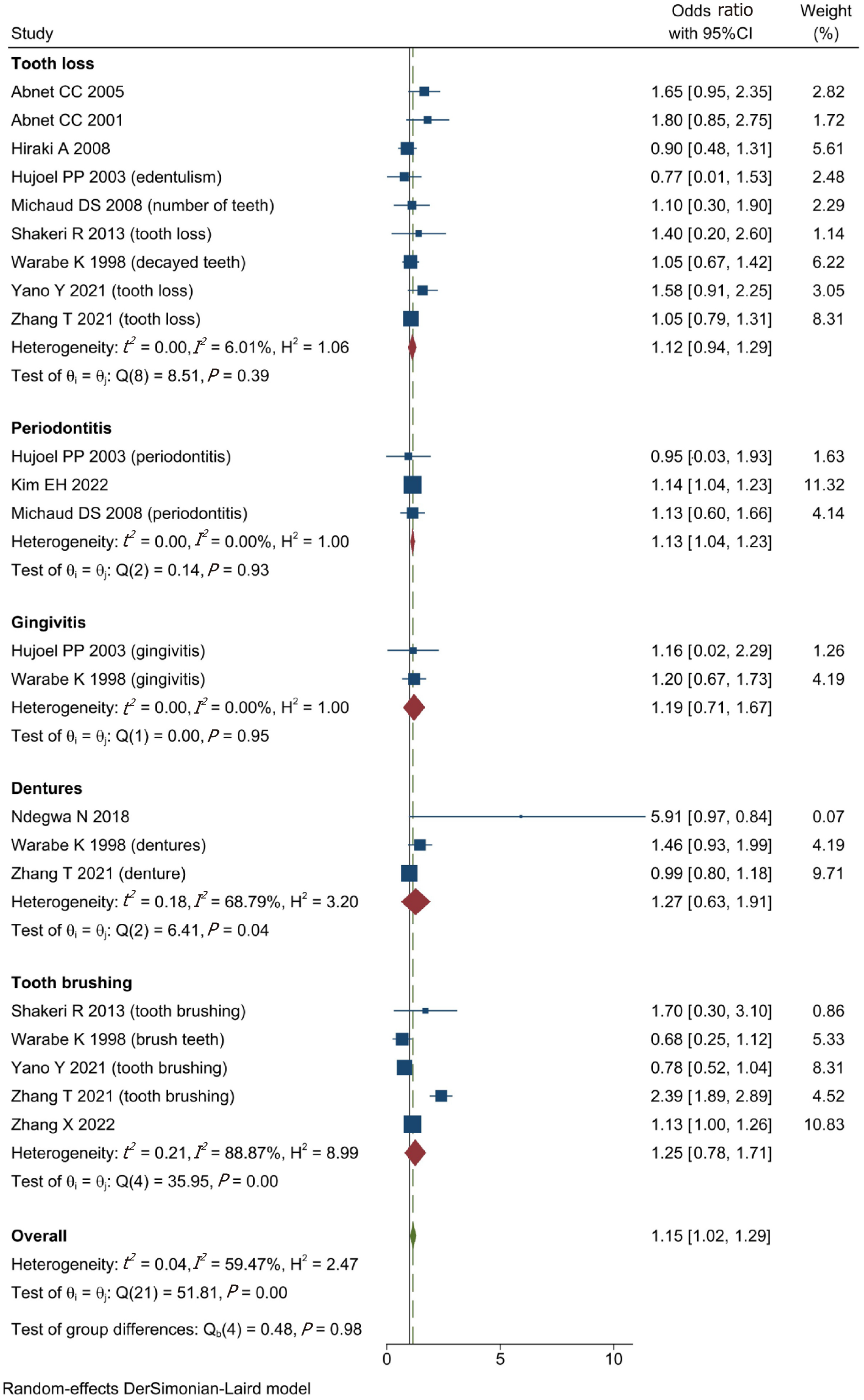

We classified oral health into five subgroups and analysed their respective effects on the risk of GC. We found that patients with periodontitis (OR = 1.13, 95%CI: 1.04-1.23; I2 = 0.00%, P < 0.01) had a greater risk of GC. However, tooth loss (OR = 1.12, 95%CI: 0.94-1.29; I2 = 6.01%, P > 0.01), gingivitis (OR = 1.19, 95%CI: 0.71-1.67; I2 = 0.00%, P > 0.01), dentures (OR = 1.27, 95%CI: 0.63-1.19, I2 = 68.79%, P > 0.01), and tooth brushing (OR = 1.25, 95%CI: 0.78-1.71, I2 = 88.87%, P > 0.01) had no effect on the risk of GC (Figure 3).

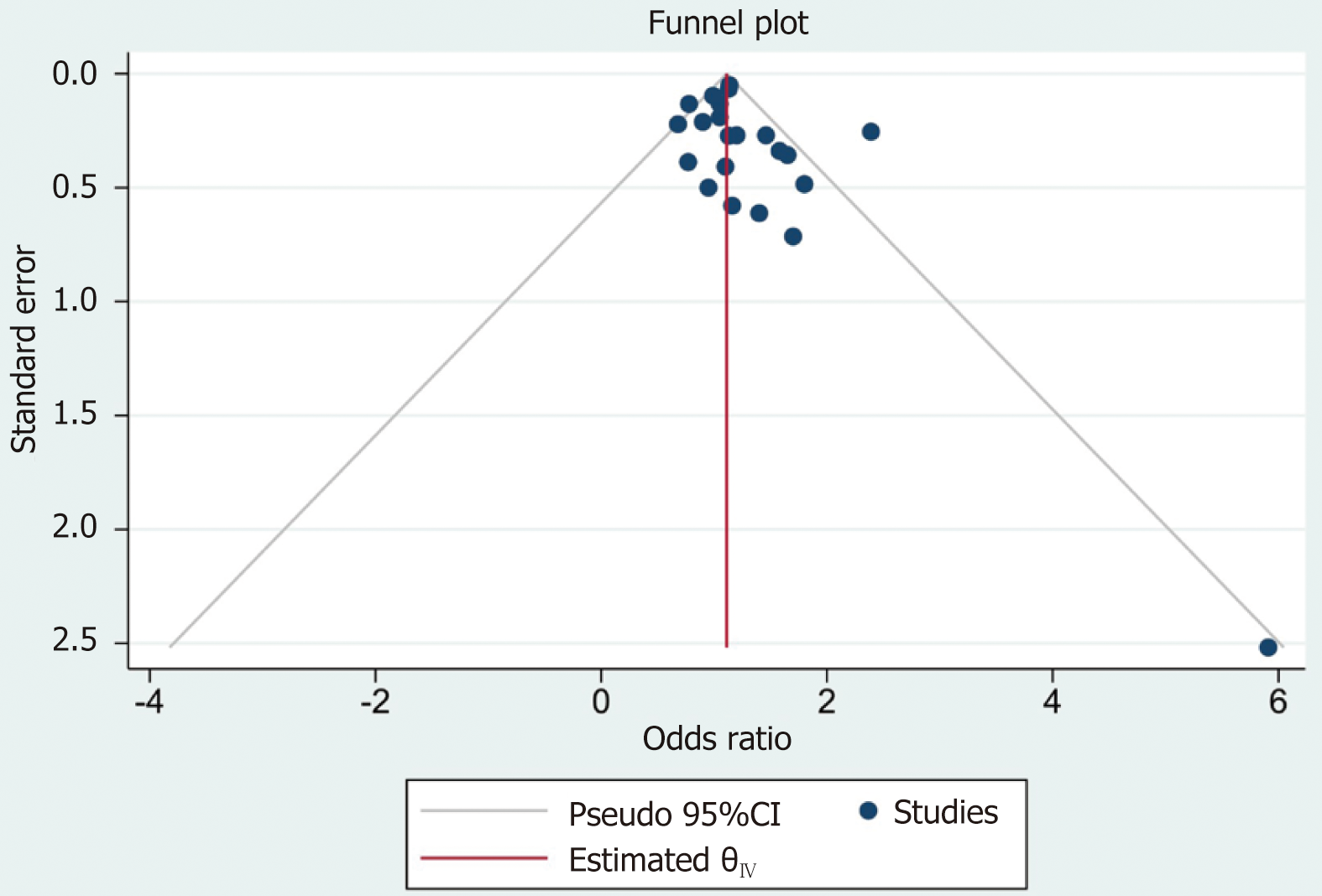

According to the data analysis, the funnel plot was relatively symmetrical, indicating low publication bias (Figure 4).

Each study was excluded each time the sensitivity was assessed. There were no significant differences in the results after each analysis was performed.

A total of 1431808 patients were enrolled from twelve studies in the present study. After the data analysis, the outcomes showed that poor oral health was associated with a greater risk of GC. We classified oral health into five subgroups: Tooth loss, periodontitis, gingivitis, dentures, and tooth brushing. After subgroup analysis, the outcomes showed that patients with periodontitis had a greater risk of GC. However, tooth loss, gingivitis, dentures, and tooth brushing had no effect on the risk of GC.

In recent years, a growing number of researchers have focused on the relationship between oral health and cancer[27,28,35,36]. Periodontitis, a common disease that affects oral health, is a chronic inflammatory disease caused by bacteria that carry the risk of supporting tissue breakdown and tooth loss[37]. Moreover, periodontitis was reported to be a predictive factor for GC[19]. With the increase in the number of GC patients in China[6], the association between oral health and the risk of GC needs more attention in the future.

However, previous studies on oral health and the incidence of GC have been controversial. Several studies reported that tooth loss was not a predictive factor for increased risk of GC[19,29,30,32]. In contrast, some studies have reported that tooth loss could increase the risk of GC[27,33]. Previous studies have shown that periodontitis increases the risk of GC[19]. However, Hujoel et al[20] and Michaud et al[29] showed that there was no association between periodontitis and the risk of GC. Therefore, it was necessary to explore the real association between oral health and the risk of GC.

In our study, we found that poor oral health, especially periodontitis, was associated with a greater risk of GC. How

To the best of our knowledge, the present study was the first to pool the risk of GC in patients who had oral health problems. Our study had a large sample size, and subgroup analysis was conducted. Moreover, the publication bias of the included studies was low. Thus, the outcomes were relatively reliable. This study has several limitations. In our study, there were more cohort studies and fewer case-control studies. Second, because of insufficient data, we lacked information on the effect of different numbers of missing teeth on the incidence of GC. Therefore, further case-control studies need to be performed in the future.

In conclusion, patients with poor oral health, especially those with periodontitis, had a higher risk of GC. Thus, patients should be concerned about their oral health. Improving oral health might reduce the risk of GC.

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the most common tumours worldwide and the forth leading cause of cancer death. Prevention of GC has become a focal point because of these worrisome numbers. Prevention of GC can be divided into primary prevention (reducing the incidence of GC) and secondary prevention (early detection and treatment). Primary prevention includes smoking cessation, reducing salt intake, increasing fruit and vegetable intake, and other health behaviours, such as oral health behaviours.

The aim of present study is to assess whether there is a relationship between oral health and the risk of GC.

The research objective was to explore the relationship between oral health and GC risk.

This study searched five databases to find eligible studies from inception to April 10, 2023. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale score was used to assess the quality of included studies. The quality of cohort studies and case-control studies were evaluated separately in this study. Incidence of GC were described by odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Funnel plot was used to represent the publication bias of included studies. We performed the data analysis by StataSE 16.

A total of 1431677 patients from twelve included studies were enrolled for data analysis in this study. According to our analysis, we found that poor oral health was associated with a high risk of GC (OR = 1.15, 95%CI: 1.02-1.29; I2 = 59.47%, P = 0.00 < 0.01), particularly periodontitis (OR = 1.13, 95%CI: 1.04-1.23; I2 = 0.00%, P < 0.01). Moreover, after subgroup analysis, tooth loss (OR = 1.12, 95%CI: 0.94-1.29; I2 = 6.01%, P > 0.01), gingivitis (OR = 1.19, 95%CI: 0.71-1.67; I2 = 0.00%, P > 0.01), dentures (OR = 1.27, 95%CI: 0.63-1.19; I2 = 68.79%, P > 0.01), or tooth brushing (OR = 1.25, 95%CI: 0.78-1.71; I2 = 88.87%, P > 0.01) had no influence on the risk of GC.

Oral health status associated with GC risk. People should focus on oral health as it might reduce the incidence of GC.

This study was extended to a multi-center study.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Arigami T, Japan; Corte-Real A, Portugal S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: ZhangYL

| 1. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 64702] [Article Influence: 16175.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (177)] |

| 2. | Cheng YX, Tao W, Liu XY, Zhang H, Yuan C, Zhang B, Zhang W, Peng D. Does Chronic Kidney Disease Affect the Surgical Outcome and Prognosis of Patients with Gastric Cancer? A Meta-Analysis. Nutr Cancer. 2022;74:2059-2066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in RCA: 55853] [Article Influence: 7979.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (132)] |

| 4. | Peng D, Zou YY, Cheng YX, Tao W, Zhang W. Effect of Time (Season, Surgical Starting Time, Waiting Time) on Patients with Gastric Cancer. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2021;14:1327-1333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359-E386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20108] [Cited by in RCA: 20516] [Article Influence: 2051.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (20)] |

| 6. | Kang B, Liu XY, Cheng YX, Tao W, Peng D. Factors associated with hypertension remission after gastrectomy for gastric cancer patients. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2022;14:743-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, Jemal A, Yu XQ, He J. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:115-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11444] [Cited by in RCA: 13215] [Article Influence: 1468.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 8. | Zhang T, Yang X, Yin X, Yuan Z, Chen H, Jin L, Chen X, Lu M, Ye W. Poor oral hygiene behavior is associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer: A population-based case-control study in China. J Periodontol. 2022;93:988-1002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Karimi P, Islami F, Anandasabapathy S, Freedman ND, Kamangar F. Gastric cancer: descriptive epidemiology, risk factors, screening, and prevention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:700-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1159] [Cited by in RCA: 1328] [Article Influence: 120.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tang X, Zhang M, He Q, Sun G, Wang C, Gao P, Qu H. Histological Differentiated/Undifferentiated Mixed Type Should Not Be Considered as a Non-Curative Factor of Endoscopic Resection for Patients With Early Gastric Cancer. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chelimo C, Elwood JM. Sociodemographic differences in the incidence of oropharyngeal and oral cavity squamous cell cancers in New Zealand. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2015;39:162-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ekheden I, Yang X, Chen H, Chen X, Yuan Z, Jin L, Lu M, Ye W. Associations Between Gastric Atrophy and Its Interaction With Poor Oral Health and the Risk for Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma in a High-Risk Region of China: A Population-Based Case-Control Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2020;189:931-941. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Printz C. African American women with gum disease and tooth loss face higher pancreatic cancer risk. Cancer. 2019;125:2719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pizzo G, Guiglia R, Lo Russo L, Campisi G. Dentistry and internal medicine: from the focal infection theory to the periodontal medicine concept. Eur J Intern Med. 2010;21:496-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kebschull M, Demmer RT, Papapanou PN. "Gum bug, leave my heart alone!"--epidemiologic and mechanistic evidence linking periodontal infections and atherosclerosis. J Dent Res. 2010;89:879-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 298] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wada T, Kunisaki C, Ono HA, Makino H, Akiyama H, Endo I. Implications of BMI for the Prognosis of Gastric Cancer among the Japanese Population. Dig Surg. 2015;32:480-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gao Z, Ni J, Ding H, Yan C, Ren C, Li G, Pan F, Jin G. A nomogram for prediction of stage III/IV gastric cancer outcome after surgery: A multicenter population-based study. Cancer Med. 2020;9:5490-5499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Pietiäinen M, Liljestrand JM, Kopra E, Pussinen PJ. Mediators between oral dysbiosis and cardiovascular diseases. Eur J Oral Sci. 2018;126 Suppl 1:26-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hiraki A, Matsuo K, Suzuki T, Kawase T, Tajima K. Teeth loss and risk of cancer at 14 common sites in Japanese. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:1222-1227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hujoel PP, Drangsholt M, Spiekerman C, Weiss NS. An exploration of the periodontitis-cancer association. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:312-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kim EH, Nam S, Park CH, Kim Y, Lee M, Ahn JB, Shin SJ, Park YR, Jung HI, Kim BI, Jung I, Kim HS. Periodontal disease and cancer risk: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Front Oncol. 2022;12:901098. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;134:178-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 1314] [Article Influence: 328.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8858] [Cited by in RCA: 12669] [Article Influence: 844.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zhang J, Yu KF. What's the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280:1690-1691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2650] [Cited by in RCA: 2993] [Article Influence: 110.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ioannidis JP. Interpretation of tests of heterogeneity and bias in meta-analysis. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;14:951-957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 351] [Cited by in RCA: 463] [Article Influence: 27.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39087] [Cited by in RCA: 46553] [Article Influence: 2116.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 27. | Abnet CC, Qiao YL, Mark SD, Dong ZW, Taylor PR, Dawsey SM. Prospective study of tooth loss and incident esophageal and gastric cancers in China. Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12:847-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Abnet CC, Kamangar F, Dawsey SM, Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, Albanes D, Pietinen P, Virtamo J, Taylor PR. Tooth loss is associated with increased risk of gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma in a cohort of Finnish smokers. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:681-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Michaud DS, Liu Y, Meyer M, Giovannucci E, Joshipura K. Periodontal disease, tooth loss, and cancer risk in male health professionals: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:550-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in RCA: 290] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ndegwa N, Ploner A, Liu Z, Roosaar A, Axéll T, Ye W. Association between poor oral health and gastric cancer: A prospective cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2018;143:2281-2288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Shakeri R, Malekzadeh R, Etemadi A, Nasrollahzadeh D, Abedi-Ardekani B, Khoshnia M, Islami F, Pourshams A, Pawlita M, Boffetta P, Dawsey SM, Kamangar F, Abnet CC. Association of tooth loss and oral hygiene with risk of gastric adenocarcinoma. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2013;6:477-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Watabe K, Nishi M, Miyake H, Hirata K. Lifestyle and gastric cancer: a case-control study. Oncol Rep. 1998;5:1191-1194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Yano Y, Abnet CC, Poustchi H, Roshandel G, Pourshams A, Islami F, Khoshnia M, Amiriani T, Norouzi A, Kamangar F, Boffetta P, Brennan P, Dawsey SM, Vogtmann E, Malekzadeh R, Etemadi A. Oral Health and Risk of Upper Gastrointestinal Cancers in a Large Prospective Study from a High-risk Region: Golestan Cohort Study. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2021;14:709-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Zhang X, Liu B, Lynn HS, Chen K, Dai H. Poor oral health and risks of total and site-specific cancers in China: A prospective cohort study of 0.5 million adults. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;45:101330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Mello FW, Melo G, Pasetto JJ, Silva CAB, Warnakulasuriya S, Rivero ERC. The synergistic effect of tobacco and alcohol consumption on oral squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig. 2019;23:2849-2859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Wang YP, Han XY, Su W, Wang YL, Zhu YW, Sasaba T, Nakachi K, Hoshiyama Y, Tagashira Y. Esophageal cancer in Shanxi Province, People's Republic of China: a case-control study in high and moderate risk areas. Cancer Causes Control. 1992;3:107-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Fu MM, Chien WC, Chung CH, Lee WC, Tu HP, Fu E. Is periodontitis a risk factor of benign or malignant colorectal tumor? A population-based cohort study. J Periodontal Res. 2022;57:284-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Shimazaki Y, Soh I, Koga T, Miyazaki H, Takehara T. Risk factors for tooth loss in the institutionalised elderly; a six-year cohort study. Community Dent Health. 2003;20:123-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860-867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10123] [Cited by in RCA: 11285] [Article Influence: 490.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 40. | Kim S, Doh RM, Yoo L, Jeong SA, Jung BY. Assessment of Age-Related Changes on Masticatory Function in a Population with Normal Dentition. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Feldman RS, Kapur KK, Alman JE, Chauncey HH. Aging and mastication: changes in performance and in the swallowing threshold with natural dentition. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1980;28:97-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Batisse C, Bonnet G, Eschevins C, Hennequin M, Nicolas E. The influence of oral health on patients' food perception: a systematic review. J Oral Rehabil. 2017;44:996-1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Nair J, Ohshima H, Nair UJ, Bartsch H. Endogenous formation of nitrosamines and oxidative DNA-damaging agents in tobacco users. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1996;26:149-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |