Published online May 27, 2022. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v14.i5.521

Peer-review started: July 31, 2021

First decision: October 3, 2021

Revised: November 10, 2021

Accepted: April 29, 2022

Article in press: April 29, 2022

Published online: May 27, 2022

Processing time: 297 Days and 13.2 Hours

We comment on a study titled “Feasibility and safety of "bridging" pancreaticogastrostomy for pancreatic trauma in Landrace pigs” in which ten pigs were randomized to either experimental “bridging” pancreaticogastrostomy (PG) or a control group with a routine mucosa-to-mucosa PG. At six months anastomoses had strictured and closed in both groups. The authors concluded that “bridging” PG is feasible and safe in damage control surgery during the early stage of pancreatic injury. In this letter we comment on the study design, specifically leaving a 2 cm gap between the pancreatic stump and the stomach and highlight the complexity of performing pancreatic anastomoses following trauma pancreaticoduodenectomy as to our experience in a high volume trauma centre. Our data emphasize that pancreatic anastomoses in trauma are complex procedures with significant postoperative morbidity and are best managed collaboratively by trauma and hepatopancreaticobiliary surgical teams with the required technical skills.

Core Tip: In the elective setting a number of different pancreatic anastomotic methods have been proposed with variations in the site of implantation (stomach or jejunum), the anastomotic technique and the use of pancreatic duct stenting. These techniques need to be adapted to the prevailing operative circumstances. We recommend a pancreaticogastrostomy rather than a pancreaticojejunostomy in the presence of severe shock, pro

- Citation: Krige J, Bernon M, Jonas E. Applying refined pancreaticogastrostomy techniques in pancreatic trauma. World J Gastrointest Surg 2022; 14(5): 521-524

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v14/i5/521.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v14.i5.521

We read with interest the research study by Feng et al[1] in the World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery entitled “Feasibility and safety of bridging pancreaticogastrostomy for pancreatic trauma in Landrace pigs” which was designed to simulate damage control surgery in pancreatic trauma[1]. In their study ten Landrace pigs were randomized into an experimental group in which a “bridging” pancreaticogastrostomy (PG) was performed while in a control group a routine mucosa-to-mucosa PG was constructed. Amylase levels in drainage fluid, fasting and two-hour postprandial blood glucose, insulin levels in peripheral blood, and insulin levels in portal vein blood were measured six months after the operation. Repeat surgery was undertaken one and six months to examine the condition of the abdominal cavity and pancreas and evaluate the patency of the PG.

After surgery, the authors found that the fasting and two-hour postprandial blood glucose levels were similar. There was also no difference in the fasting and two-hour insulin values of postprandial peripheral blood and portal vein blood six months after the operation between the two groups. One month after the operation, the tract in the bridging group and the conventional PG were patent. However, after six months both groups had strictured and closed with chronic pancreatitis present in both. The authors concluded that a “bridging” PG is a practical and secure method of damage control surgery during the initial management of a pancreatic injury.

The authors are to be congratulated on this innovative study evaluating a “bridging” PG in order to overcome the difficulties related to a PG after trauma. All pancreatic surgeons will concede that the pancreatic anastomosis is the Achilles’ heel of pancreatic surgery, especially so when circumstances are unfavorable, as occurs in pancreatic trauma. The authors acknowledge that using this method the bridging tubes invariably became dislodged with time and that all the PG anastomoses eventually strictured with resultant chronic pancreatitis in both groups. We are however puzzled why the authors left a 2 cm gap between the pancreatic stump and the stomach bridged by the tube because this space will inevitably fibrose and stricture. Intuitively it makes more sense to create a sutured and stent-splinted apposition PG which provides a tight seal without a gap between the pancreas and stomach and would theoretically be less prone to fibrosis and stricturing. Two further observations which test the validity of their study are that the operations undertaken on the pigs were elective procedures which did not simulate a pancreatic trauma situation as occurs in reality, nor do the authors provide any evidence in their study that the bridging procedure is indeed quicker than a conventional anastomosis.

We, too, have grappled with the complexities of establishing a safe method for a pancreatic anastomosis in pancreatic trauma[2]. Our clinical experience is based on one of the largest active databases of complex pancreatic injuries in the world. We have shown that when a trauma pancreaticoduodenectomy has been completed, several important assessments are necessary with regard to the timing and type of reconstruction. The crucial factor in the eventual result is the quality of the pancreatic anastomosis. As is relevant during elective resections, the pancreatic to bowel anastomosis after a pancreaticoduodenectomy for trauma is the Achilles’ heel of the operation and a leak from the pancreatic anastomosis failure is the most important reason for the considerable incidence of complications which may occur after the operation. Even when the pancreatic anastomosis is performed during elective operations the fistula rate is significant and the incidence is greatest in patients who have a soft pancreatic parenchyma when combined with a small main pancreatic duct. These important risk factors which are relevant when the pancreas is injured are further aggravated by a pancreas that is may be hemorrhagic, as well as a jejunal wall thickened by edema, which makes the circumstances even more difficult and hazardous for a sound anastomosis.

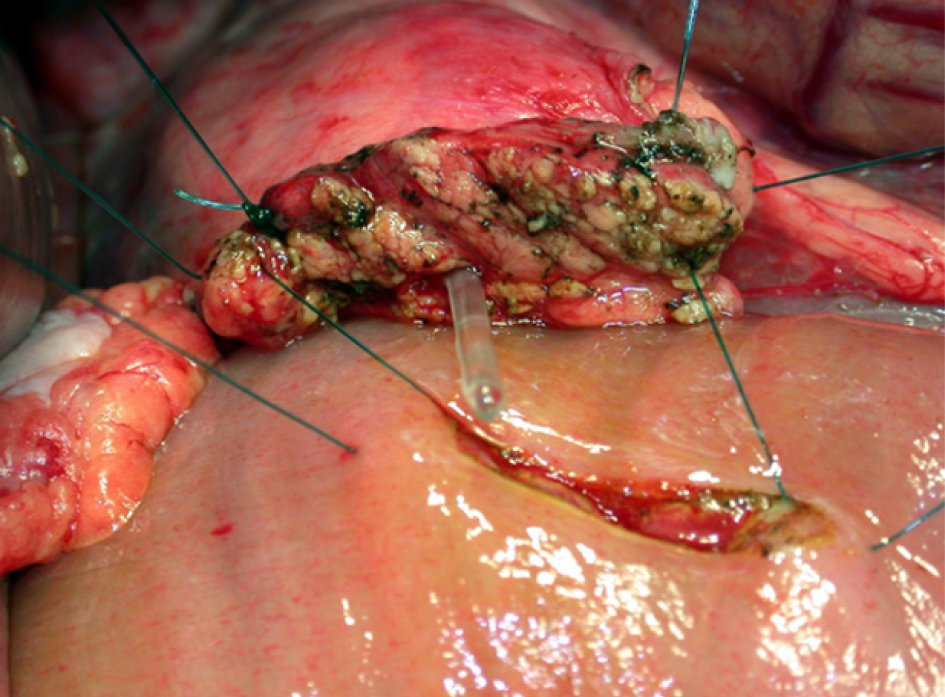

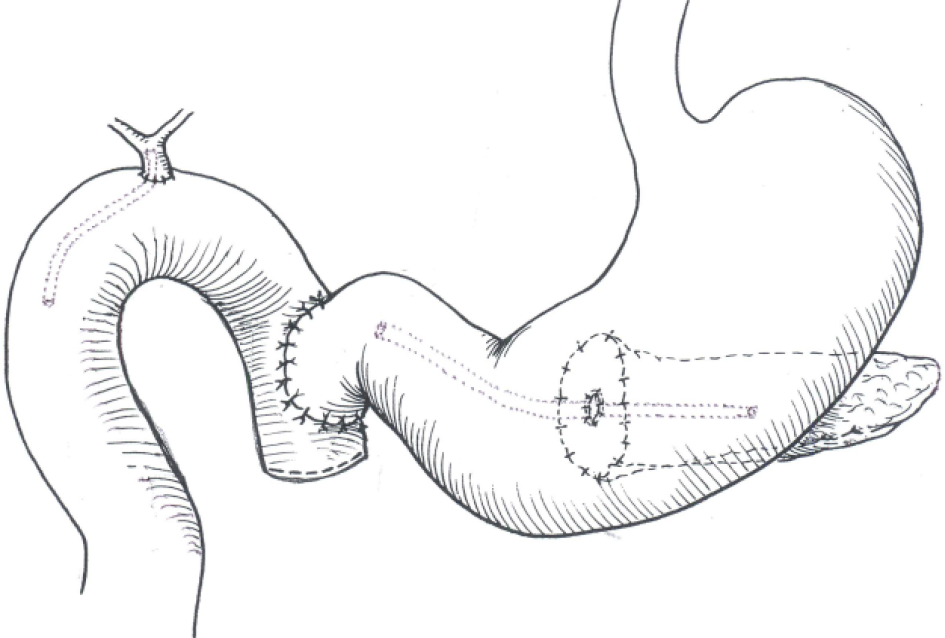

During elective surgery several techniques have been suggested to minimize the possibility of pancreatic fistulas occurring after the operation. These include the location of implantation (stomach or jejunum), the technique used for the anastomosis and whether a stent is used to splint the pancreatic duct and bowel. These techniques may need to be modified according to the existing conditions. PG and pancreaticojejunostomy each have their own benefits and disadvantages but neither are consistently appropriate after a serious pancreatic injury where edema and substantial damage to tissues are critical influences deciding whether a particular type or method should be used in the anastomotic reconstruction. In our clinical studies we routinely used a PG when prolonged hypotension, extended fluid resuscitation and associated venous injuries resulted in an edematous small bowel which jeopardized the anastomosis. Under these unfavorable conditions there are several rational and technical reasons for doing a PG in preference to a pancreaticojejunostomy. The posterior gastric wall is conveniently contiguous to the pancreatic remnant and approximation is never a problem. The gastrostomy can be created to the precise dimension required without any difference in size to allow a tension-free anastomosis. In addition, the gastric wall is thick, sutures hold well, has a generous blood supply and is less likely than the jejunum to develop ischemic complications. Gastric and pancreatic secretions are easily drained via a well-placed nasogastric tube after a PG and the pancreatic exocrine enzymes remain inactivated with a low pH in the absence of enterokinase. We prefer to use a modified single layer interrupted suture technique which includes the pancreatic capsule and parenchyma and we routinely place a 5 Fr silastic intraluminal stent rather than to attempt a more complicated duct to mucosa technique which escalates the level of complexity (Figure 1). If circumstances dictate we apply the Imanaga method of reconstruction which, with minor modifications, allows endoscopic access to the biliary system subsequently if required for retrieval of biliary stents and balloon-enhanced cholangiography through the duodenojejunal anastomosis (Figure 2).

Our data emphasize that pancreatic anastomoses in trauma are technically complicated procedures which may have substantial sequelae postoperatively and are best treated collaboratively by trauma and hepatopancreaticobiliary surgical teams who have the requisite technical skills to recognize and deal with high-risk pancreatic anastomoses.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: South Africa

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Li JT, China S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Feng J, Zhang HY, Yan L, Zhu ZM, Liang B, Wang PF, Zhao XQ, Chen YL. Feasibility and safety of "bridging" pancreaticogastrostomy for pancreatic trauma in Landrace pigs. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2021;13:419-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Krige JE, Jonas E, Thomson SR, Kotze UK, Setshedi M, Navsaria PH, Nicol AJ. Resection of complex pancreatic injuries: Benchmarking postoperative complications using the Accordion classification. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;9:82-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |