INTRODUCTION

The redundant colon represents an unusually lengthened large bowel folded up upon itself, forming extra loops, tortuosities and kinks. The redundancy may involve the entire colon or it may be limited to certain areas as the hepatic flexure, transverse colon, splenic flexure, but the distal colon especially the region of the sigmoid is the most commonly affected. There has long been a debate about whether a redundant colon gives rise to symptoms like constipation and volvulus. The objective of this review is to critically examine this issue.

Embryological development of the colon

The development of the midgut in the embryo is characterized by a rapid elongation of the gut and its mesentery, resulting in formation of the primary intestinal loop. The cephalic limb of the loop develops into the distal part of the duodenum, the jejunum, and part of the ileum. The caudal limb becomes the lower portion of the ileum, the caecum, the appendix, the ascending colon and the proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon. In adults, the junction of the cranial and caudal limb can only be recognized if a portion of the vitelline duct persists as a Meckel's diverticulum[1]. Coinciding with the growth in length, the primitive intestinal loop rotates around an axis formed by the superior mesenteric artery. Subsequently, elongation of the small intestinal loop continues, forming coiled loops. Similarly, the large intestine grows considerably in length, but fails to participate in the coiling phenomenon. At the end of the third month, the intestinal loops return to the abdominal cavity from the extra-embryonic coelom. The caecal bud is temporarily located in the right upper quadrant below the liver before it descends into the right iliac fossa, thereby forming the ascending colon and hepatic flexure. The distal end of the caecal swelling forms a narrow diverticulum, the appendix. As the intestine returns to the abdominal cavity, their mesenteries are pressed against the posterior abdominal wall where they fuse with the parietal peritoneum, fixing the right and left colon. The colon is now as it is in the adult.

ANCIENT ANATOMIC OBSERVATIONS OF THE COLON

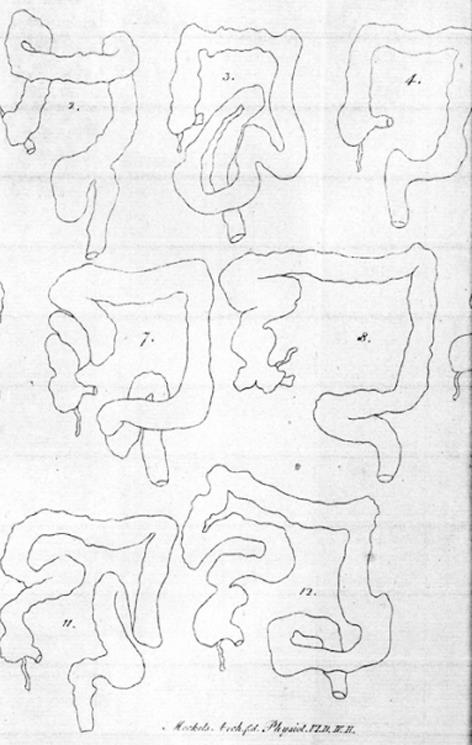

In 1820, Monterossi[2] noted from autopsies an increased length of the colon, which was depicted in handmade drawings showing sigmoid loops and duplication of the right and left colonic flexure (Figure 1). Treves[3] dissected the bodies of patients who died from reasons other than abdominal diseases. He was convinced that the length of the bowel was independent of age, height, and weight. In the full-term fetus, he found that the length of the intestine, and especially the colon, was significantly constant. Shober[4] reported 18 cases selected from different investigators between 1826 and 1896 in which the sigmoid flexure was found on the right side of the pelvis. Various other abnormalities were reported, including a caecum in the right hypochondriac region with extensive mesentery. It seems that the colon was likely to vary in length and in mode of disposition more than any other part of the intestinal canal[5]. This was further demonstrated by Black[6] in a series of drawings from textbooks and journal papers between 1836 and 1911, showing a multitude of displacement and elongation of the left colon. The hepatic and splenic flexures were permanently in place.

Figure 1 Handmade drawings of dolichocolon forming tortuosities, loops and kinks.

From Monterossi[2], 1820.

Bryant[7] measured the intestines after removed from the body. His data showed that Treves[3] was incorrect in stating that all children start life with practically the same length of intestine. He found great variations in the small intestine and colon before the fifth month of fetal life. At the age of 10 years, the child has a length of colon considered normal for the adult. He also found that the colon varied in length from 1.25 to 2.00 m, with an average length of 1.52 m. Furthermore, he reported that the length of the colon increased about 20 cm between 20 and 80 years of age.

NEWER OBSERVATIONS OF COLON LENGTH

Phillips et al[8] reported colon length from several studies of cadavers, using laparotomy, barium enema or CT-colonography, between 1955 and 2015. The mean length of the colon varied between 109.0 cm and 169.0 cm. A redundant colon with loops was not mentioned. In their own study, they found a significant proportion of colons had mobility of the ascending and descending segments, with the length of the latter being highly variable. This may indicate loose redundancies.

RADIOLOGY OF DOLICHOCOLON

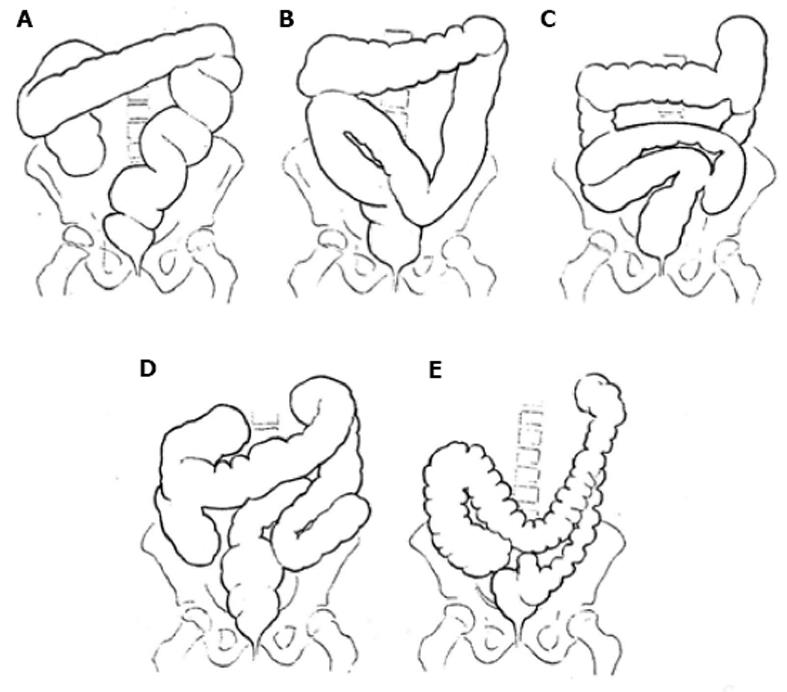

By combining a bismuth meal and a bismuth clysma, Kienböck[9] was the first to visualize a redundant colon. An extremely long mobile descending colon and sigmoid ran from the left flexure through the abdomen up under the liver and then distally superimposed to the ascending colon and caecum, before joining the rectum. A few years later, Lardennois and Aubourg[10] using the same technique demonstrated various redundancies in all parts of the colon, in both adults and children. These investigators named the anatomic variant dolichocolon (dolicho-, Greek: long). During the following years, many case-series with all positions of colonic redundancies were published, using this new X-ray technique[11-14]. The colon length or that of the redundancies was not measured. Years later, the redundant colon was characterized by the following criteria: a sigmoid loop rising over the line between the iliac crests, a transverse colon below the same line and extra loops at the hepatic and splenic flexure. A fully developed dolichocolon occurs when all redundancies are present simultaneously[15-17] (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2 Different types of dolichocolon.

A-C: Redundancies in the sigmoid; D: Generalized redundancies; E: Low transverse colon. From Caffey[16], 1961.

Figure 3 Barium enema showing a fully developed dolichocolon: A sigmoid loop rising over the line between the iliac crests, a transverse colon below the same line and extra loops at the flexures.

A long colon may result in an incomplete colonoscopy, as demonstrated in a study in which the colorectal length was 45 cm longer than the length in a group who underwent complete colonoscopy[18].

ETIOLOGY OF DOLICHOCOLON

Redundancy of the colon is a far from seldom variant. In 1934, Kantor[19] reported 258 cases from 1614 patients who underwent roentgenography, an incidence of 16.0%. However, Moeller[13] found redundant colon in 18 out of 744 cases, an incidence of 2.4%. A high incidence of 28.5% was found among 562 cases reported by Larimore[12], and in 116 newborn infants, he found redundancy with the same frequency and variation as in adults. In cadavers, Bryant[7] reported an incidence of 14% among 242 subjects. Thus, redundancy seems to occur at any age, in either sex, and without special preference to any habitus[20].

For the next half century, the interest in redundant colon seemed to wane. The prevalence of dolichocolon in a population is not known, because healthy people have not been investigated for that purpose. The closest to such an evaluation is a study by Brumer[21] in which 53 patients had a barium enema for reasons other than constipation; one patient (1.9%) had a redundant colon. In 2009, Raahave et al[17] published a study of 236 patients with constipation disorders, finding high frequencies of colonic redundancies.

The question for many authors has been whether dolichocolon is a congenital anatomic variant, an abnormal growth, or pathological stretching. Treves[3] and Bryant[7] assumed that colon growth is associated with activity and function depending on the diet. Very recently, the large bowel was shown in mice to undergo substantial changes in length, as it fills with fecal matter, and that the stretching of longitudinal muscles results in slow colonic transit[22]. However, using barium enema, several authors have shown that fetuses, newborns, and infants exhibit colonic redundancies[10,12,23]. Recently, colonic elongation has been shown in children by nuclear transit scintigraphy[24]. A familiar occurrence of dolichocolon has also been observed[25]. In general, there are great variations in the frequency and positions of redundancies. Most investigators have found them to occur in the middle and left side of the colon[11,12,17,23].

Thus, dolichocolon is mainly congenital, but function and fecal transport may also promote some changes.

SYMPTOMS FROM THE REDUNDANT COLON

The dominating symptom of dolichocolon is constipation[4,6,9,13,14,19,23,25,26], and patients have died from it[5]. In 1962, Brumer[21] examined 106 patients with chronic constipation using barium enema and found 32 (30.2%) had a redundant colon. Among 53 controls, only one (1.9%) had a colon with redundancies. He concluded that a causal connection must exist between this anomaly and constipation. The most common related cause of constipation after anorectal myectomy was later found to be a redundant colon[27]. When evaluating patients with slow transit constipation, the cause was always associated with dolichocolon[28]. Recently, a high proportion of patients with constipation disorders was shown to have redundant colon[17].

Pain sometimes cramp-like, often occurs in the lower abdomen[4,11,13,17,19,23,25], where a tender mass may sometimes be felt[6,17,19]. Constipation and pain are often followed with distension, and many cases demonstrate how much these patients have suffered.

Non-specific symptoms have also been linked to redundant colon, such as general weakness, headache, and mild fever attacks suggested to be caused by a toxic condition because of fecal stasis[4,10,23,29]. In the beginning of the 20th century, a theory of autointoxication was formulated[30], but then discredited among little proof of bacterial toxin production. However, immune activation is detected in constipated patients based on levels of CD3+, CD4+, CD8+, and CD25+ T-cells and by spontaneous proliferation of lymphocytes. T-cell activation, elevated levels of antibacterial antibodies, and a tendency towards elevated concentrations of IgG, IgM, and circulating immune complexes, provide evidence of the stimulation of systemic cellular and humoral immunity in chronic constipation[31].

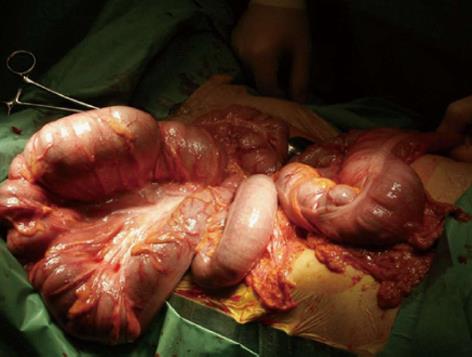

An elongated colon is often associated with a failure of agglutination of the mesentery with the parietal peritoneum. Consequently, the elongated colon is not fixed to the dorsal wall and can swing free on a long mesentery (Figure 4), and loose redundant loops have a potential risk of volvulus.

Figure 4 Dolichocolon with loose mesenteries allowing the colon to be drawn out of the abdomen: The transverse colon is localized at the right, and the sigmoid loop at the left.

FUNCTION OF A REDUNDANT COLON

Information to the function of a redundant colon is scarce. Atony and a weak muscular tone may be limited to the site of the redundancy[14] or dysfunction may be the result of derangement of the autonomous intestinal nervous system[32]. Kantor[19] suggested that constipation varies directly with colon length, and Metcalf et al[33] later stated that transit is largely proportional to the length and volume of a colon segment. In an overview, Müller-Lissner et al[34] stated that, although a long colon could prolong stool residence time, no studies have correlated colonic transit time with colon length. Subsequently, Raahave et al[17] demonstrated that the mean colon transit time was 36.26 h in patients without redundancies, 43.80 h in those with one redundancy, 41.65 h in those with two redundancies, and 52.27 h in those with three to four redundancies. The mean colon transit time of 44 controls was 24.75 h. The difference in colon transit time between the four levels of redundancies was significant. Abdominal pain, bloating, and infrequent defecation increased significantly with an increased number of redundancies. A separate analysis found a significant positive correlation between colon transit time and fecal load and a redundant sigmoid colon.

In studies of patients undergoing subtotal colectomy for slow transit constipation, the majority of colon specimens were significantly redundant[35-38]. Colon transit time is meant to be a measure of the speed of fecal propulsion through the colon, and an even distribution of radiopaque markers suggests the same function of all parts of the colon, including redundancies. Possible reasons for dysmotility are disorders of the enteric nervous system, neuroendocrine system or brain-gut axis, including lack of interstitial cells of Cajal[39].

DIAGNOSIS OF DOLICHOCOLON

A redundant colon should be suspected in patients with constipation, abdominal pain, distension and seldom defecation, especially when symptoms have been present from childhood. However, these symptoms may also come from pure functional colonic disorders, which is why many patients with dolichocolon have not received a diagnosis. A colon transit study and a barium enema or CT-colonography is needed to confirm the diagnosis. This is essential in guiding therapy.

TREATMENT OF CONSTIPATION

From the very beginning, chronic constipation was suggested to be treated with enemas, mineral oil, other laxatives, abdominal massage, a supporting corset, and eventually sedatives[4,10,11]. Murray[40] focused on diet and advocated cereals containing husk, as well as the use of salads, raw fruits and vegetables, that grow above the ground. Large quantities of water must be taken, and moderate use of weak tea and coffee is allowed, but no alcoholic beverages. The colonic content was lubricated with oil and a tincture of belladonna given three times a day to increase the intestinal tone. In addition, abdominal electrotherapy was used over the abdomen, just as an afternoon siesta took place since the patients tire very easily. Short walks were advised as exercise. A mild sedative was eventually added[14]. The intervention was discontinued, when the function of the colon was restored, except the retention enema with oil and high residue diet may be more or less a permanent part of the regimen. The majority of patients with a redundant colon who are given this treatment will then return to a state of approximate well-being. In the subsequent years, most authors agreed with these principles[23,29,32,41]. A gap of interest in redundant colon then followed for nearly half a century. In general, redundancy of the colon was regarded as an unimportant observation.

Redundant colon is not mentioned in a European Perspective of Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Constipation[42] or in the current American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement on Constipation[43]. This is a surprise, considering existing knowledge. Patients with constipation disorders and a redundant colon have had improvements in their quality of life by a fiber-rich diet supplemented with husk, sufficient water intake, a prokinetic drug, and physical activity[39]. Apart from the prokinetic drug, current treatment resembles the regimen of a hundred years ago.

SURGERY FOR DOLICHOCOLON

Immediate surgery was advocated when a sigmoid loop is twisted (volvulus)[11,20,23,29,41]. In this context, it is notable that sigmoid volvulus accounts for a disproportionally high number of cases of intestinal obstruction in developing countries such as Africa (20%-45%) compared to developed countries (1%-7%). In addition, sigmoid volvulus occurs in much younger patients[44]. Today, it will first be tried to straighten out the twisted loop by an endoscopic maneuver. If this fails, acute surgery is necessary.

Most authors advise against surgery for dolichocolon[11,19,23,32,41]. Lane[30] introduced colectomy for chronic constipation with a death rate of 20.5%, but without giving any information with regard to colon anatomy among 39 patients. Subtotal colectomy for a redundant colon was mentioned as a possibility in 1914[10]. However, resection of colonic segments was performed with satisfactory results in five cases[45] and without improvement in three cases[13]. In 1960, Davis[46] presented the results of 14 children operated on for symptomatic dolichocolon resistant to conservative treatment. No failures occurred, and the results were excellent in eight patients, good in three, and fair in three. Hollender[25] reported good functional results after various colonic resections in 11 patients with dolichocolon. In other studies of patients who underwent subtotal colectomy for slow transit constipation, the majority of colon specimens were significantly redundant[35-37].

In 15 patients, the cause of constipation was slow colonic transit, which was associated with dolichocolon[28]. After hemicolectomy or colectomy, the patients received daily evacuations and experienced less pain. Recently 31 patients with slow transit constipation and a dolichocolon underwent colectomy[38]. At follow-up, most patients reported daily defecation and no uncontrolled diarrhea. Abdominal pain was very seldom and patient satisfaction high.

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

The prevalence of dolichocolon is not known, because population based investigations have not been made. However, in projects with colonoscopic screening for cancer it may be possible to estimate the number and localization of colonic redundancies. Colorectal length may be determined by magnetic resonance imaging or by tracking the progression of an electromagnetic capsule[47]. It will hopefully then be possible to determine the prevalence of dolichocolon and a causal relationship to constipation and volvulus.

CONCLUSION

Dolichocolon is an anatomic variant with redundancies of the colonic segments and flexures. The diagnosis is established by barium enema or CT-colonography. Accumulating data from 200 years shows dolichocolon is congenital and causes constipation. Treatment is conservative, and only patients refractive to this therapy may undergo a subtotal colectomy. A redundant loop may cause volvulus, requiring an endoscopic maneuver or surgery. Future research has to show the prevalence of dolichocolon in a population and to determine whether it always gives rise to constipation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author is thankful to Jette Meelby, librarian, The Library of Health Sciences, Hilleroed Hospital for retrieving ancient articles, which made the study possible.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Denmark

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Maric I, Shah OJ, Sukocheva OA S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Yan JL