Published online Feb 15, 2016. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v8.i2.231

Peer-review started: July 10, 2015

First decision: September 30, 2015

Revised: November 18, 2015

Accepted: December 7, 2015

Article in press: December 8, 2015

Published online: February 15, 2016

Processing time: 211 Days and 21.9 Hours

Neuroendocrine tumors of the gastrointestinal tract are rare neoplasms. Rectal neuroendocrine tumors consist approximately the 5%-14% of all neuroendocrine neoplasms in Europe. These tumors are diagnosed in relatively young patients, with a mean age at diagnosis of 56 years. Distant metastases from rectal neuroendocrine tumors are not very common. Herein we describe a case of a rectal neuroendocrine tumor which metastasized to the lung, mediastinum and orbit. This case underscores the importance of early identification and optimal management to improve patient’s prognosis. Therefore, the clinical significance of this case is the necessity of physicians’ awareness and education regarding neuroendocrine tumors’ diagnosis and management.

Core tip: Rectal neuroendocrine tumors consist approximately 5%-14% of all neuroendocrine neoplasms in Europe. Distant metastases from rectal neuroendocrine tumors are not very common. Herein we describe a case of a rectal neuroendocrine tumor with an uncommon natural history as well as a review of the literature. The present case underscores the importance of early identification and management of these tumors.

- Citation: Tsoukalas N, Galanopoulos M, Tolia M, Kiakou M, Nakos G, Papakostidi A, Koumakis G. Rectal neuroendocrine tumor with uncommon metastatic spread: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2016; 8(2): 231-234

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v8/i2/231.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v8.i2.231

The gastrointestinal tract has the largest component of neuroendocrine cells. In spite of this, neuroendocrine tumors of the colon and rectum are rare entities, with a reported incidence ranging from 0.3% to 3.9% of all colorectal malignancies[1]. Τhe introduction of more sensitive diagnostic tools (e.g., immunohistochemical stains) and an overall increased awareness among physicians, have largely contributed to the rising incidence of neuroendocrine tumors[2]. Here we describe an interesting case of a rare neuroendocrine neoplasm of the rectum with an uncommon natural history.

A 54-year-old man with free medical or family history came to our hospital reporting rectal bleeding in May 2005. Colonoscopy demonstrated a rectal polypoid mass, 15 mm in diameter, located 6 cm from the anus. Biopsies were taken and histopathology evaluation showed an adenocarcinoma which invaded submucosa. An extensive work up with computed tomography (CT) scans was negative for distant metastases but there was an infiltration of pericolic fat. After that, the patient underwent low anterior resection of the rectum and the mesorectum. The histopathological examination of the dissected specimen showed a grade 2 adenocarcinoma with infiltration of pericolic fat and regional lymph nodes (stage C1 Astler-Coller). Adjuvant chemotherapy with 6 cycles of FOLFOX4 was administered without radiotherapy.

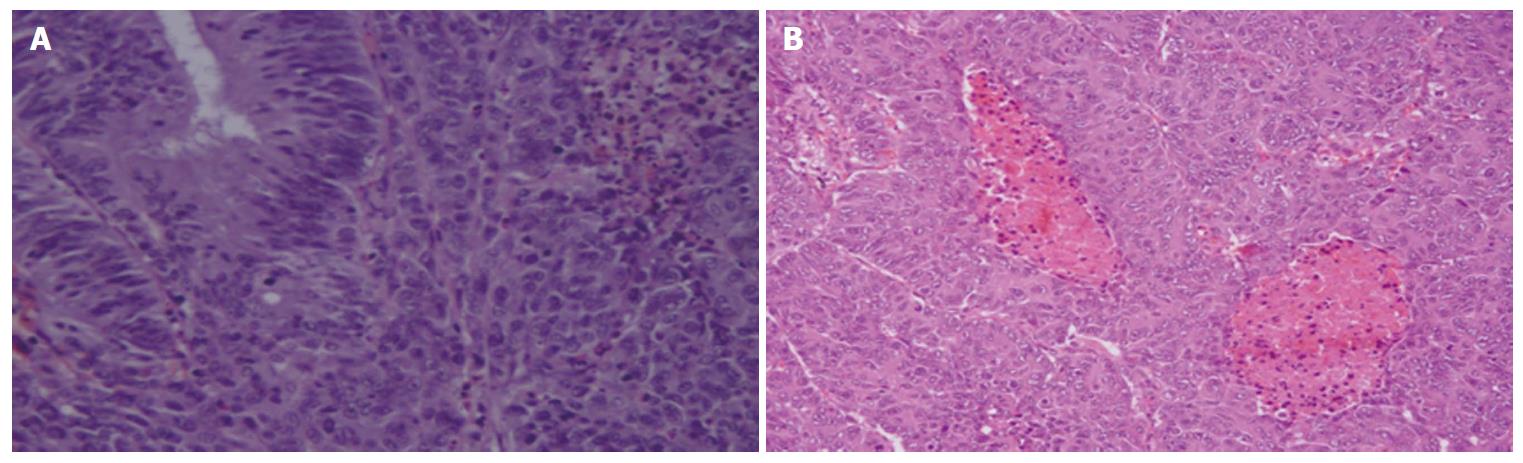

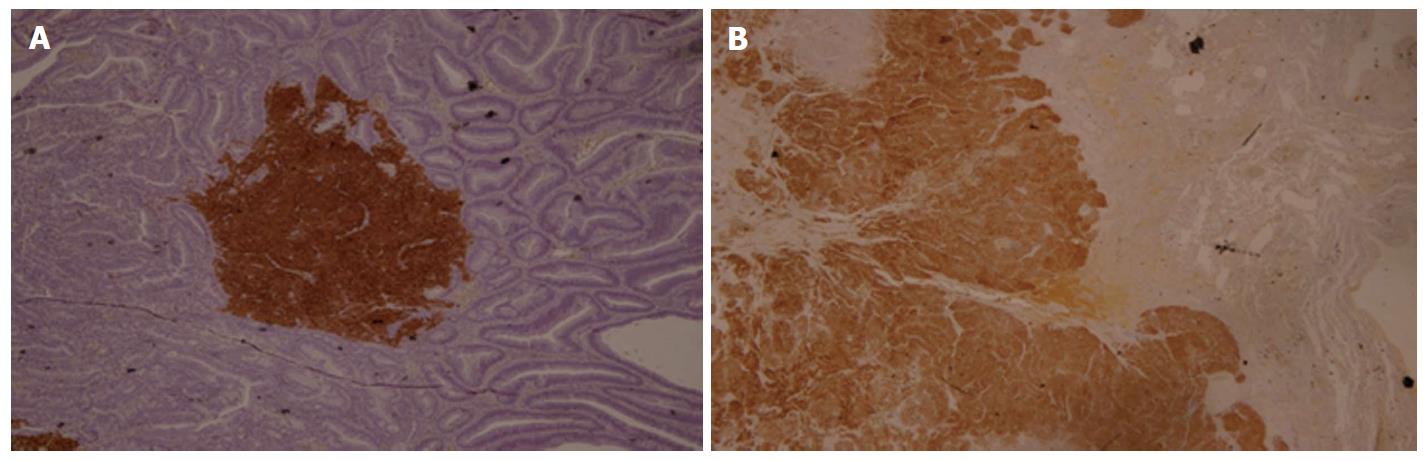

Two years later, during the scheduled follow-up, the CT scans revealed a mass in the lower left lobe of the lung, which was surgically resected and the pathology showed a neuroendocrine tumor with well differentiation. The review of both histologic specimens (paraffin tube of rectum and lung specimens, Figures 1 and 2) showed that there were medium to large tumor cells, displaying a trabecular growth pattern with nuclear pleomorphism, hyperchromasia and prominent nucleoli. Tumor cells were often spreading individually infiltrating. No lymphovascular invasion was detectable. There were a few punctate foci of necrosis. The tumor cells invaded perirectal tissues and 2 regional lymph nodes were infiltrated. Pathologic staging was pT3N1M1 and the clinical stage IV. Moreover, the immunohistochemistry analysis revealed positivity, in both specimens, for CK18, CK20, chromogranin, synaptophysin, CD56 and Ki-67, while CK7 and TTF1 were negative. Synaptophysin and chromogranin showed a diffuse positive staining of the tumor cells. These findings led to the conclusion that the primary tumor was that in the rectum and it was a neuroendocrine neoplasm well differentiated. In particular, Ki-67 was 8%-9% and the tumour was classified as well differentiated neuroendocrine tumor, intermediate grade (G2 NET). At that time patient refused to receive any further treatment.

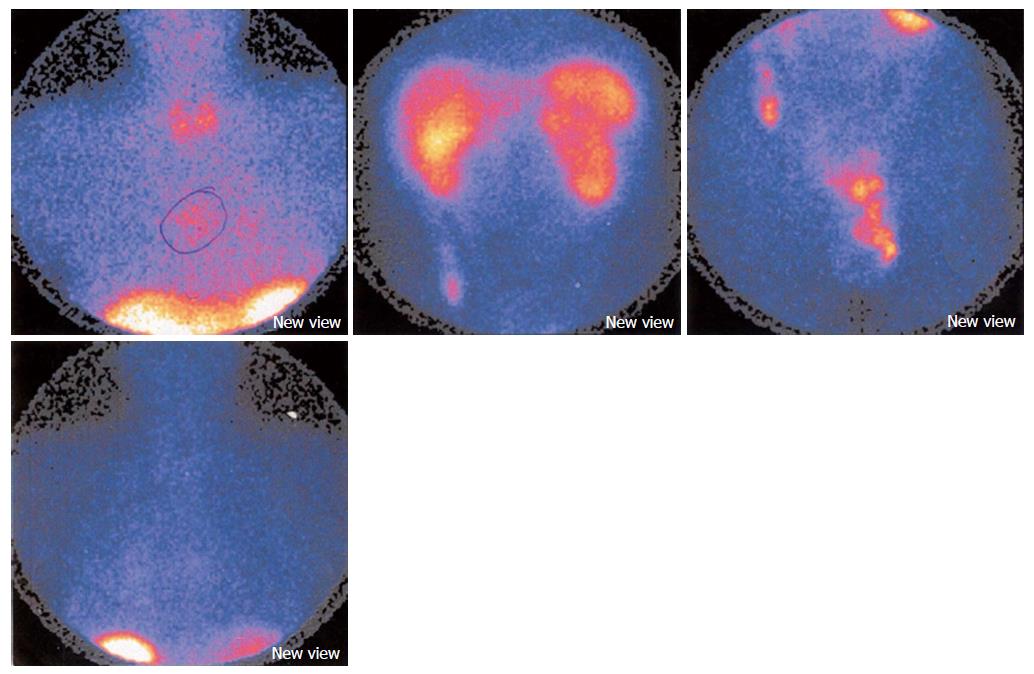

One year later the planned follow-up showed a mass in the mediastinum. The octreoscan that followed showed increased uptake in the same anatomic region (Figure 3). Subsequently, the patient underwent radiotherapy (44 Gy) for the mass in the mediastinum. Moreover, the patient developed a mass in the left orbit, something that was discovered after a bilateral visual impairment and was treated with stereotactic radiosurgery (Cyber-Knife 18 Gy). Despite the medical advices patient refused to receive any systemic treatment. At the same period of time new lesions in left lung, mediastinum, adrenals and scalp were found. The patient was administered chemotherapy with the regiment Cisplatin 75 mg/m2 d1 plus Etoposide 100 mg/m2 d1-d3. Unfortunately, patient died after 4 cycles of chemotherapy due to uncontrolled systemic infection.

Rectal neuroendocrine neoplasms are usually small; polypoid lesions located in the mid-rectum, 5 to 10 cm from the anal verge and are submucosal in location, mainly discovered incidentally on routine surveillance endoscopies. If there are any symptoms, they include rectal bleeding, pain (as happened in our case) and change in bowel habits. However, 50% of patients are asymptomatic[3].

They belong to a heterogeneous group of tumours, which all present a common phenotype with immunoreactivity for markers such as chromogranin A and synaptophysin[4,5]. Neuron-specific enolase (NSE) and CD56 are frequently expressed in GEP-NETs, but are not specific. At present, immunohistochemistry for Ki-67 (MIB-1) is mandatory to grade the tumor according to the 2010 World Health Organization (WHO) classification and divides the tumors into NET G1, NET G2 and poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC G3)[4].

Prognostic factors for metastases are tumor size, depth of invasion, and lymph node involvement of the rectal NETs. These factors may be assessed by transrectal ultrasound, if feasible, and pelvic MRI. One study revealed that metastases emerged in only 2% of tumors not bigger than 2 cm, which had not infiltrated the muscularis propria, compared to 48% of those infiltrating the muscularis layer[6]. Although neuroendocrine tumours metastasize in 50%-75% of patients with the most common sites being lymph nodes, liver, and bones, metastases to the orbits, as happened in our case, have only rarely been reported (about 32 cases until 2006) and are believed to occur through hematogeneous spread[7]. Orbital neuroendocrine tumors tend to arise from the gastrointestinal tract, whereas bronchial neuroendocrine tumors show a propensity to uveal metastasis and typically present with a mass or diplopia while visual failure is unusual[8], characteristics that verified in our case.

Obviously, metastatic disease at diagnosis will suggest a worse prognosis despite the available treatment options. In fact, surgery may have a palliative role to the complications associated with an advanced rectal tumour mass[9]. Adjuvant therapy for well differentiated tumours after surgery is not considered, although an argument exists for applying chemotherapy in non-differentiated tumours with incomplete resection[3]. Well differentiated neuroendocrine tumors is an uncommon indication for systemic chemotherapy[10]. When used for progressive disease, streptozotocin combined with 5-fluorouracil with or without doxorubicin is most often applied even though the response rate is < 25%[4]. The effectiveness of systemic chemo-regimens is optimal in poorly-differentiated tumours and the combination of cisplatin or carboplatin and etoposide have showed satisfactory results[4]. Newer anti-angiogenesis or mTOR inhibitors may be used as well as peptide receptor radionuclide therapy peptide in patients with advanced or metastatic disease[4,11]. Additionally, more chemotherapy regimens such as temozolomide and capecitabine are under clinical investigation for patients with advanced or metastatic neuroendocrine neoplasms[12].

In conclusion, rectal neuroendocrine tumors are rare and cases with distant metastases are even rarer. This case underscores the necessity of physicians’ awareness and education regarding neuroendocrine tumors’ diagnosis and management.

A 54-year-old man with rectal bleeding.

A rectal polypoid mass, 15 mm in diameter.

Rectal neuroendocrine tumor; Non-neoplastic polyp; Lung neuroendocrine tumor.

A well differentiated rectal neuroendocrine tumor (G2 NET) with metastases to left lung, mediastinum and left orbit.

Computed tomography scans revealed masses in the lower left lobe of the lung, in the mediastinum and in the left orbit.

The histopathological examination showed a well differentiated rectal G2 NET.

Chemotherapy with 6 cycles of FOLFOX4 at the beginning and then regimen Cisplatin 75 mg/m2 d1 plus etoposide 100 mg/m2 d1-d3.

This is an interesting case report describing a potentially malignant behavior of a primary neuroendocrine tumor of the rectum.

P- Reviewer: Freeman HJ, Kir G, Lakatos PL, Paraskevas KI, Scheidbach H S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Christiano AB, Gullo CE, Palmejani MA, Marques AM, Barbosa AP, Basso MP, de Lima LG, Netinho JG. Neuroendocrine tumor of the anal canal. GE J Port Gastrenterol. 2012;19:267-269. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Saclarides TJ, Szeluga D, Staren ED. Neuroendocrine cancers of the colon and rectum. Results of a ten-year experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:635-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ramage JK, Goretzki PE, Manfredi R, Komminoth P, Ferone D, Hyrdel R, Kaltsas G, Kelestimur F, Kvols L, Scoazec JY. Consensus guidelines for the management of patients with digestive neuroendocrine tumours: well-differentiated colon and rectum tumour/carcinoma. Neuroendocrinology. 2008;87:31-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Öberg K, Knigge U, Kwekkeboom D, Perren A. Neuroendocrine gastro-entero-pancreatic tumors: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23 Suppl 7:vii124-vii130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 307] [Cited by in RCA: 337] [Article Influence: 28.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Simon SR, Fox K. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the colon. Correct diagnosis is important. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1993;17:304-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Naunheim KS, Zeitels J, Kaplan EL, Sugimoto J, Shen KL, Lee CH, Straus FH. Rectal carcinoid tumors--treatment and prognosis. Surgery. 1983;94:670-676. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Peixoto RD, Lim HJ, Cheung WY. Neuroendocrine tumor metastatic to the orbit treated with radiotherapy. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2013;5:177-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mehta JS, Abou-Rayyah Y, Rose GE. Orbital carcinoid metastases. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:466-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Schindl M, Niederle B, Häfner M, Teleky B, Längle F, Kaserer K, Schöfl R. Stage-dependent therapy of rectal carcinoid tumors. World J Surg. 1998;22:628-633; discussion 634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rosenberg JM, Welch JP. Carcinoid tumors of the colon. A study of 72 patients. Am J Surg. 1985;149:775-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Teunissen JJ, Kwekkeboom DJ, de Jong M, Esser JP, Valkema R, Krenning EP. Endocrine tumours of the gastrointestinal tract. Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:595-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Koumarianou A, Kaltsas G, Kulke MH, Oberg K, Strosberg JR, Spada F, Galdy S, Barberis M, Fumagalli C, Berruti A. Temozolomide in Advanced Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Pharmacological and Clinical Aspects. Neuroendocrinology. 2015;101:274-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |