Published online Mar 15, 2011. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v3.i3.43

Revised: February 3, 2011

Accepted: February 10, 2011

Published online: March 15, 2011

AIM: To evaluate long-term outcomes in a large series of patients who randomly received laparoscopic or open colorectal resection.

METHODS: From February 2000 to December 2004, six hundred sixty-two patients with colorectal disease were randomly assigned to laparoscopic (LPS, n = 330) or open (n = 332) colorectal resection. All patients were analyzed on an intention-to-treat basis. Long-term follow-up was carried out every 6 mo by office visits. In 526 cancer patients five-year overall and disease-free survival were evaluated. Median oncologic follow-up was 96 mo.

RESULTS: Eight (4.2%) LPS group patients needed conversion to open surgery. Overall long-term morbidity rate was 7.6% (25/330) in the LPS vs 11.1% (37/332) in the open group (P = 0.17). In cancer patients, five-year overall survival was 68.6% in the LPS group and 64.0% in the Open group (P = 0.27). Excluding stage IV patients, five-year local and distant recurrence rates were 32.5% in the LPS group and 36.8% in the Open group (P = 0.36). Further, no difference in recurrence rate was found when patients were stratified according to cancer stage.

CONCLUSION: LPS colorectal resection was associated with a slightly lower incidence of long-term complications than open surgery. No difference between groups was found in overall and disease-free survival rates.

- Citation: Braga M, Pecorelli N, Frasson M, Vignali A, Zuliani W, Carlo VD. Long-term outcomes after laparoscopic colectomy. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2011; 3(3): 43-48

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v3/i3/43.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v3.i3.43

Laparoscopic (LPS) colorectal resection is becoming routine practice because of its advantages in postoperative recovery and cosmesis[1,2]. LPS allows a safe oncologic resection and recent trials reported that LPS did not adversely affect the chance of cure of colorectal cancer[2-4].

The vast majority of studies comparing LPS with open surgery are focused on short-term postoperative outcome. Few data have been published so far on long-term post operative morbidity after laparoscopic colorectal resection. There are few studies comparing the effect of LPS with open colorectal resection in terms of long-term complications in cancer patients.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate long-term outcomes in a large series of patients who randomly received laparoscopic or open colorectal resection. In cancer patients five-year overall and disease-free survival were also evaluated.

From February 2000 to December 2004, adult patients admitted for colorectal disease were assessed for study eligibility. Inclusion criteria were age ≥ 18 years and suitability for elective surgery.

Exclusion criteria were cancer infiltrating adjacent organs assessed by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, cardiovascular dysfunction (New York Heart Association class > 3), respiratory dysfunction (arterial PO2 < 70 mmHg), hepatic dysfunction (Child-Pugh class C), ongoing infection, and plasma neutrophil level < 2.0 × 109/L.

The protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of the San Raffaele Hospital. The potential participants had the study design explained and then were required to sign a written informed consent before randomization.

Eligible participating patients were randomly allocated to LPS or open colorectal surgery. Lists randomized according to the site of the lesion were generated by a computer program. Assignments were made by means of sealed sequenced masked envelopes which were opened, before the induction of anesthesia, by a nurse unaware of the trial design.

On hospital admission, the following variables were recorded: age; gender; primary diagnosis; Body mass index (BMI) (weight in kilograms/height in square meters); presence of comorbidity assessed according to the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score; serum albumin (g/L); serum hemoglobin (g/L).

Undernutrition was defined as weight loss > 10% with respect to usual body weight in the six-month period before admission. Obesity was defined as BMI > 30.

All the operations were performed by the same well-trained surgical team (Braga M, Vignali A and Zuliani W), according to the technique previously reported[1,5]. In the LPS group, division of the vascular pedicle and colonic or rectal transection were performed intracorporeally. A Knight-Griffen anastomosis was fashioned in all patients who underwent left colonic or rectal resection. The anastomosis was performed intracorporeally in the LPS group. An extracorporeal hand-sewn anastomosis was fashioned in all patients who underwent right colectomy.

All patients were treated on a strictly controlled protocol with regard to bowel preparation, antibiotic prophylaxis, and postoperative care[1].

In all patients follow-up was carried out every six months by office visits. Four trained members of the surgical staff who were not involved in the study registered long-term complications.

In cancer patients, CEA serum level and computed tomography (CT) scans were performed every six months, and colonoscopy every twelve months.

All patients were analyzed on an intention-to-treat basis. Descriptive data are reported as mean (standard deviation), 95% confidence interval (CI), or number of patients and percentage.

Comparison between groups for discrete variables was made by the chi-square test or the Fisher’s exact test when appropriate. Student’s t-test was used to compare normally distributed variables. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to estimate the distribution of disease-free and overall survival. The long-rank test was used to compare time-to-event distribution. The P value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance (two-tailed test).

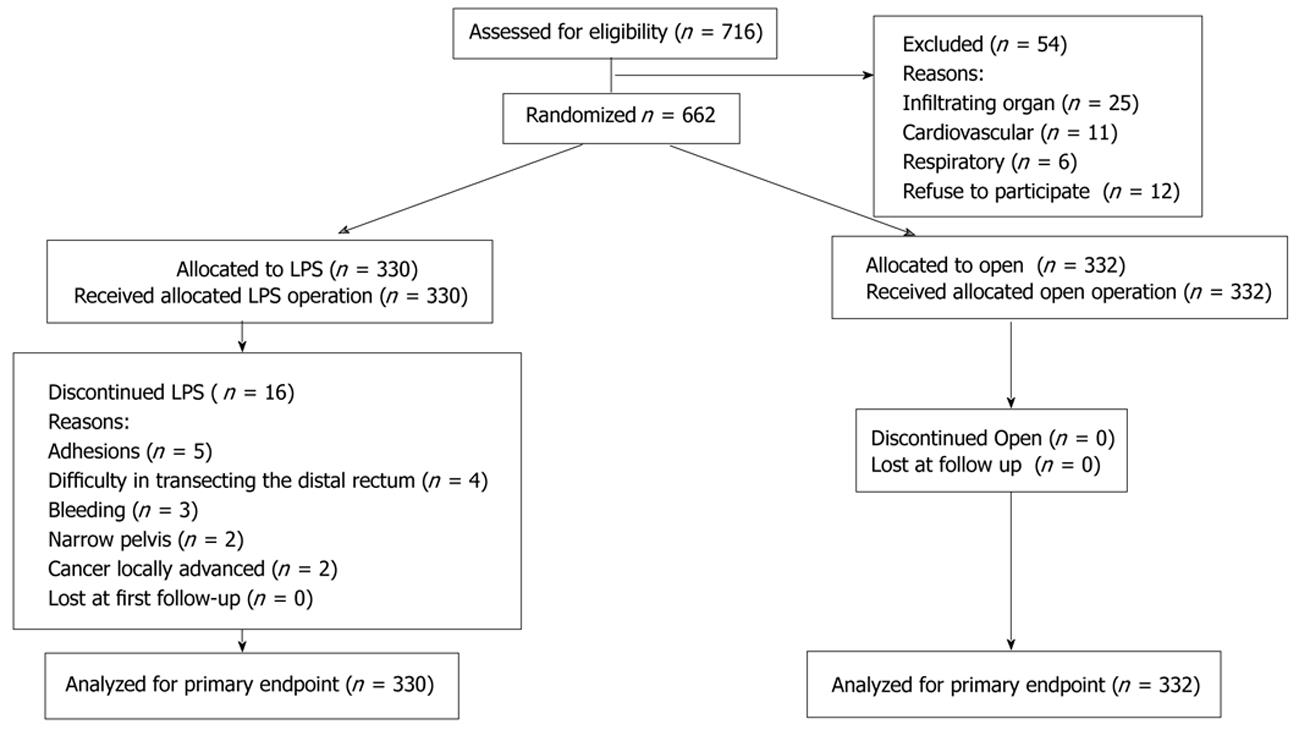

Figure 1 shows the diagram of the trial according to the CONSORT statement. During the study period, 716 patients were assessed for eligibility. Fifty-four patients were excluded from randomization because they met exclusion criteria. The remaining 662 patients were randomly allocated to the open group (n = 332) or to LPS group (n = 330).

The two groups were well balanced for demographics, perioperative variables, type of procedure, and cancer stage (Table 1). No difference between groups was found with respect to the number of lymph nodes collected. Distal margins were cancer-free in all patients, whereas circumferential margins were positive in three patients who underwent rectal resection, one in the LPS group and two in the open group. No Stage IV patient underwent synchronous major liver resection for metastasis. Eight patients (4.2%) in the LPS group who needed conversion to open surgery (adhesion n = 5, narrow pelvis n = 3) remained in the LPS arm for data analysis.

| LPS (n = 330) | Open (n = 332) | |

| Age (yr) | 63.5 (13.2) | 65.6 (12.6) |

| Male/Female ratio | 182/148 | 186/146 |

| ASA score | 1.98 (0.8) | 2.06 (0.7) |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 12.6 (2.4) | 12.4 (2.6) |

| Obesity | 26 (7.9%) | 17 (5.1%) |

| Undernutrition | 32 (9.7%) | 35 (10.5%) |

| Albumin (g/L) | 37.1 (6.8) | 36.9 (6.3) |

| Cancer | 258 (78.2%) | 268 (80.7%) |

| STAGE | ||

| I | 56 (21.7%) | 49 (18.3%) |

| II | 76 (29.5%) | 70 (26.1%) |

| III | 92 (35.7%) | 103 (38.4%) |

| IV | 35 (13.6%) | 46 (17.2%) |

| Resection of the rectum | 83 | 85 |

| Left colonic resection | 134 | 134 |

| Right colectomy | 113 | 113 |

Adjuvant chemotherapy was given to 118 (62.1%) patients of the LPS group and to 124 (61.6%) patients of the open group (P = 0.98).

The overall long-term morbidity was 7.6% in the LPS group and 11.1% in the open group (P = 0.17) (Table 2). The rate of incisional hernia was almost twice as high in patients who underwent open surgery (P = 0.12) compared to LPS patients.

| LPS (n = 330) | Open (n = 332) | P-value | |

| Overall1 | 25 (7.6%) | 37 (11.1%) | 0.17 |

| Incisional hernia | 12 (3.6%) | 22 (6.6%) | 0.12 |

| Intestinal obstruction | 3 (0.9%) | 4 (1.2%) | 0.99 |

| Abdominal abscess | 2 (0.6%) | 3 (0.9%) | 0.99 |

| Urinary dysfunction | 2 (0.6%) | 4 (1.2%) | 0.68 |

| Fecal incontinence | 6 (1.8%) | 8 (2.4%) | 0.79 |

| Anastomosis stenosis | 5 (1.5%) | 4 (1.2%) | 0.99 |

No significant difference was found between LPS and open groups in any of the three major procedures. Late hospital readmission was necessary in 39 patients, 15 (4.5%) LPS vs 24 (7.2%) open (P = 0.19). Eight patients (3 LPS, 5 open) readmitted for intestinal obstruction were successfully managed with conservative therapy. The remaining 31 readmitted patients required reoperation (12 LPS vs 19 open, P = 0.28) (Table 3).

| LPS (n = 330) | Open (n = 332) | P-value | |

| Incisional hernia | 7 (2.1%) | 14 (4.2%) | 0.19 |

| Intestinal bstruction | 3 (0.9%) | 4 (1.2%) | 0.99 |

| Anastomotic tenosis | 2 (0.6%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0.99 |

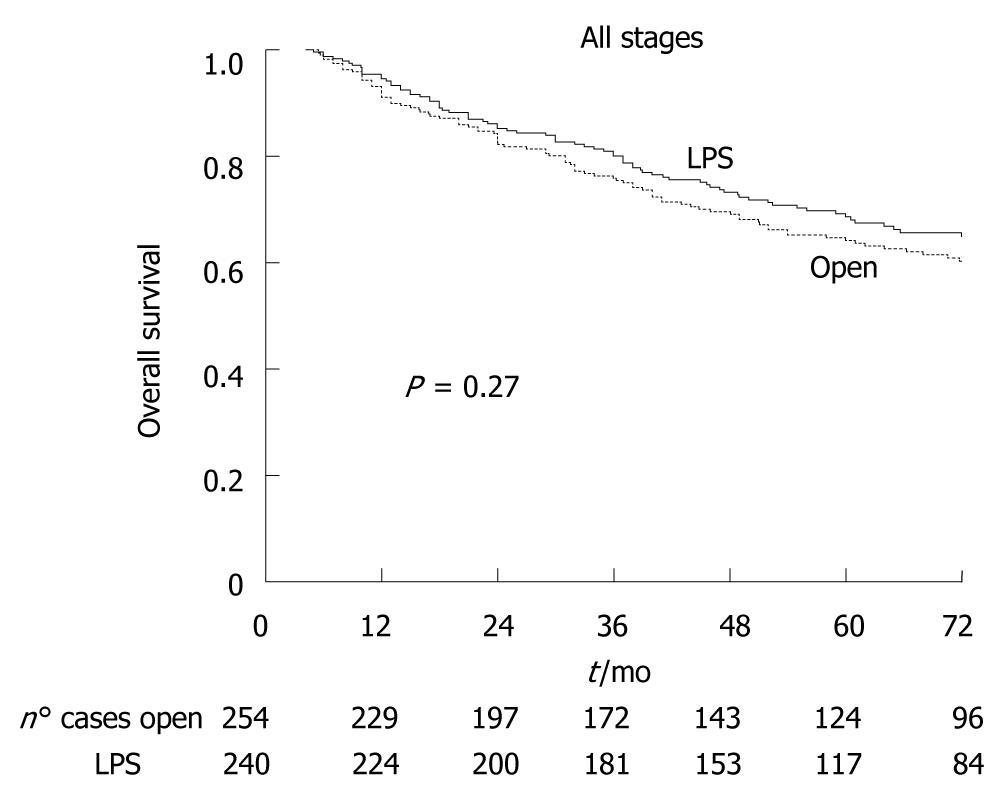

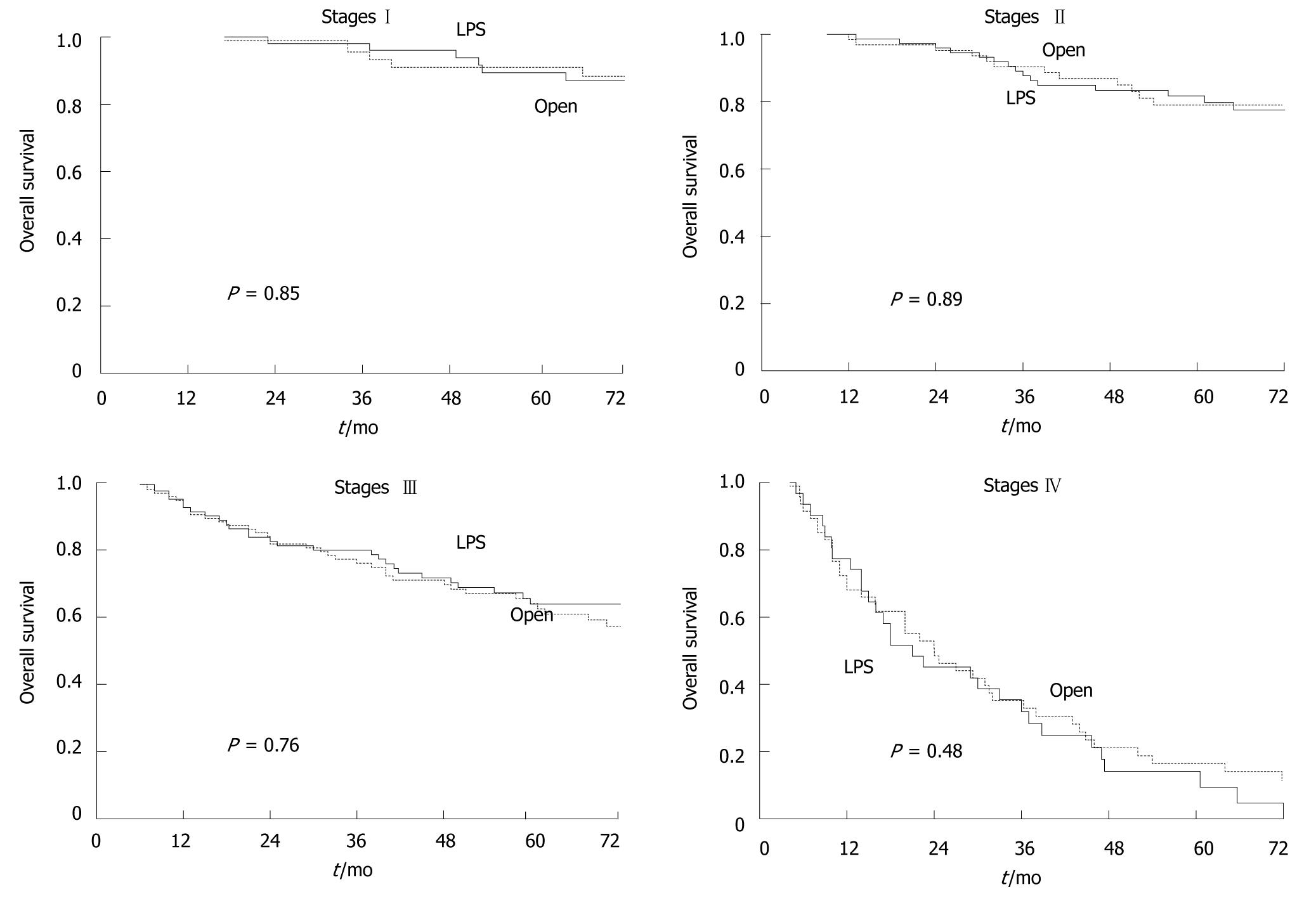

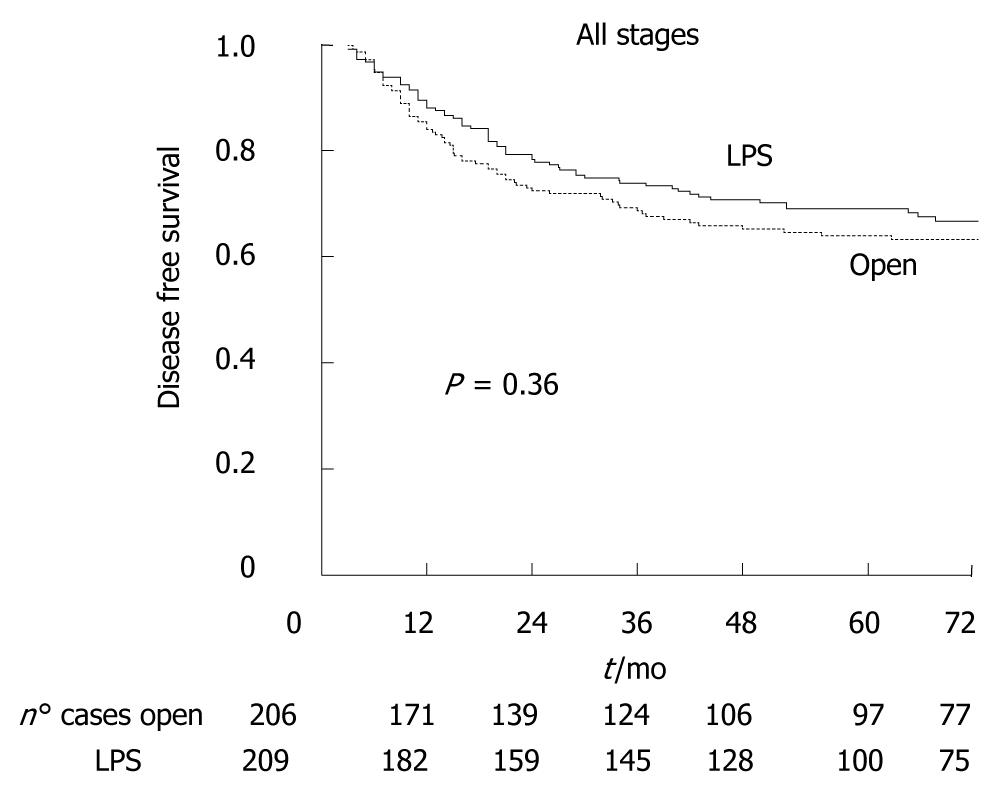

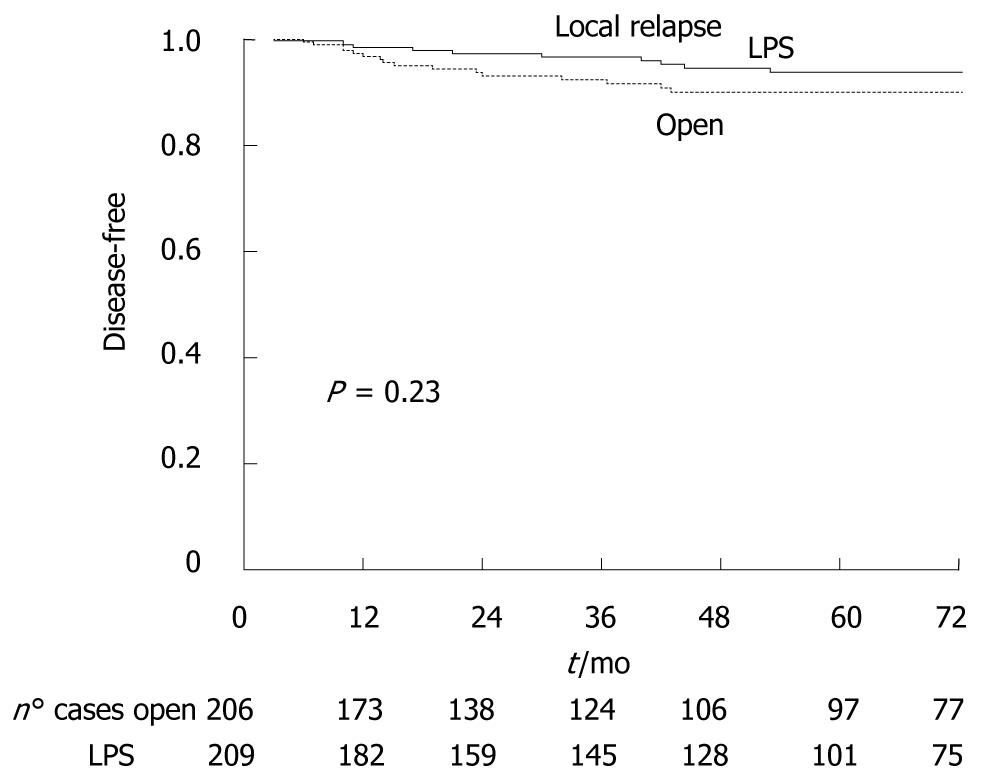

Of the 526 cancer patients, 32 (6.1%) were lost at follow-up (18 LPS, 14 open). The median oncologic follow-up was 96 mo (range 66-126 mo). Figure 2 shows that five-year overall survival was 68.6% in the LPS group and 64.0% in the open group (P = 0.27). Figure 3 shows that there was also no significant difference between LPS and open groups when patients were stratified according to cancer stage. Figure 4 shows five-year disease-free survival in the 415 patients with non-metastatic disease at time of surgery. Excluding stage IV patients, five-year disease-free survival was 67.5% in the LPS group (n = 63/209), and 63.2% in the open group (71/206), (P = 0.36).

The analysis of five-year disease-free survival was also carried out stratifying for stage of cancer. No significant differences were found between the groups in five-year disease-free survival for any of the three stages: 85.8% vs 79.1%, in stage I patients (P = 0.37), 76.8% vs 76.1% in stage II patients (P = 0.84), 47.9% vs 47.9% in stage III patients (P = 0.98).

In the LPS group one port site recurrence was found (0.48%), while in the open group one patient developed a wound site recurrence (0.49%).

As showed in Figure 5, local recurrence occurred in 27 patients: 10 (5.3%) in the LPS group, 16 (7.7%) in the open group (P = 0.43). Stratifying data by type of procedure, local relapse occurred more frequently in patients who underwent rectal resection (15/168, 8.9%) with no difference between LPS (n = 7/83) and open group (8/85), (P = 0.66).

Systemic relapse occurred in 55 (26.3%) cancer patients of the LPS group and in 59 (28.6%) cancer patients of the open group (P = 0.99).

The present randomized series is one of the largest from a single center reported so far. It incorporates a subgroup of patients included in a previous study[6]. The two groups were similar in terms of cancer stage and this allows good comparability of patients in long-term follow-up.

In the LPS group the overall number of long-term complications was lower than in the open group, although the difference was not statistically significant. The incisional hernia rate was the main difference in favour of LPS group and could be explained by both shorter length of surgical incision and lower wound infection rate in the LPS group[1]. No difference was found between the groups in the number of patients who developed intestinal obstruction due to adhesions and requiring late hospital readmission and reoperation. This is contrary to the expectation that the less invasive laparoscopic technique should reduce postoperative adhesions, thus potentially lowering the risk of intestinal obstruction.

A randomized trial comparing LPS and open surgery did not find any difference in the occurrence of either incisional hernia or adhesion syndrome at three years follow-up[7].

In a case-matched series with a 2.5-year follow-up, Duepree et al[8] reported a fivefold lower incidence of incisional hernia after LPS compared with open surgery (2.4 vs 12.9 percent). However, in another non-randomized trial including 104 patients undergoing elective colorectal resection, with a median follow-up of 22 mo, no significant difference in incisional hernia rates was found (LPS 9.3 vs open 15.8 percent)[9]. Moreover, a three-fold reduction of postsurgical small bowel obstruction episodes was found in the LPS group in two non-randomized trials[8,9].

In providing curative surgery for colorectal cancer, laparoscopic procedures must fulfil a number of criteria. The oncologic quality of the resected specimen must be at least as good as in open surgery with high vessel ligation, complete lymph node dissection, and adequate resection margins. Consequently, the long-term oncologic results of laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer must be at least equivalent to those for open surgery.

In our study there was no difference in the number of lymph nodes harvested between the laparoscopic and open group. A meta-analysis including 1536 patients found a similar mean number of lymph nodes in the laparoscopically resected specimens (11.8 ± 7.4) and in the open colectomy specimens (12.2 ± 7.8)[10]. Moreover, positive resection margins were found in 2.1% of open colectomy specimens vs 1.3% of laparoscopic specimens (odds ratio, 1.8; 95% CI: 0.7-4.5; P = 0.23). These findings are mirrored in the study published by Jackson and colleagues[11].

The question raised by the earliest series as to whether port-site metastases or other forms of recurrence would cause inferior oncologic outcomes from laparoscopy-assisted colon resection as compared with open surgery now appears to be resolved[12-14]. Prevention of port-site recurrence requires a careful technique avoiding any injury to the colon and minimizing manipulation of the tumor[15]. Pulling large specimens through a small incision should be avoided and the routine protection of the wound with a plastic device can prevent tumor inoculation[16,17]. In the current trial only one patient of the laparoscopic group developed port-site recurrence and one patient in the open group wound-site recurrence.

The results from large multicenter and single institution trials have proved that laparoscopic colorectal surgery does not adversely affect oncologic outcome at 3-5 years follow-up[18,19]. In addition, two recent meta-analyses found similar oncologic outcomes when comparing LPS and open surgery[8,9].

In our study, overall survival and disease-free survival rates at five-year follow-up were comparable in the two groups. These results are consistent with the COST trial, which found a five-year overall survival of 74.6% with laparoscopic resection vs 76.4% with open surgery (P = 0.93)[19]. Disease-free survival was 68.4% and 69.2% respectively, (P = 0.94).

Results from a single-center trial showed that overall survival (P = 0.048), cancer-related survival (P = 0.02), and being free of recurrence (P = 0.048) were significantly higher in the laparoscopic-assisted colectomy group in a series of 73 stage III patients[20].

Lacy and colleagues suggest that effector cells of nonspecific immune response, that is, natural-killer cells, which are thought to be crucial in tumor cell immunosurveillance, are suppressed to a greater extent in the early postoperative period following open colectomy compared with laparoscopy assisted colectomy[20-22].

In conclusion, LPS colorectal resection was associated with a slightly lower incidence of long-term complications when compared to open surgery. No difference between groups was found in overall and disease-free survival rates.

The vast majority of studies comparing laparoscopic with open surgery are focused on short-term postoperative outcome. Few data have been published so far on long-term postoperative morbidity after laparoscopic colorectal resection.

Laparoscopic colorectal resection is becoming routine practice because of its advantages in postoperative recovery and cosmesis. However, there are few studies comparing the effect of laparoscopic with open colorectal resection in terms of long-term complications in cancer patients. In this study, the Authors demonstrate that laparoscopic colorectal resection did not adversely affect long-term outcome when compared with open surgery.

There are few studies comparing the effect of laparoscopic vs open colorectal resection on long-term complications in cancer patients. A randomized trial did not find any difference in the occurrence of both incisional hernia or adhesion syndrome at three years follow-up. The present randomized series is one of the largest from a single center reported so far. The two groups were similar in terms of cancer stage, making patients highly comparable in a long-term follow-up. The authors’ results support laparoscopy as the standard approach in patients undergoing colorectal resection.

Since long-term postoperative morbidity and oncologic follow-up showed similar results, this study clearly supports the suggestion that laparoscopy should be preferred to conventional open approach in patients undergoing elective colorectal resection.

The laparoscopic approach allows minimally invasive surgery, meaning very small abdominal incisions, bloodless technique, and reduction of both postoperative inflammatory response and immunosuppression after surgery. Furthermore, laparoscopy has been associated with earlier recovery, better cosmesis and quality of life.

This is the following article of “Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open left colonic resection. Br J Surg 2010 Aug; 97(8): 1180-1186”. Therefore this is not completely new article. But the author made an additional large series of laparoscopic or open colorectal resection study. The number of patients is good enough for analysis for demonstrating non-inferiority of LPS.

Peer reviewer: Satoru Takayama, MD, Department of Gastroenterological Surgery, Nagoya City University, 1 Kawasumi, Mizuho-cho, Mizuho-ku, Nagoya 467-8601, Japan

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Hughes D E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Braga M, Vignali A, Gianotti L, Zuliani W, Radaelli G, Gruarin P, Dellabona P, Di Carlo V. Laparoscopic versus open colorectal surgery: a randomized trial on short-term outcome. Ann Surg. 2002;236:759-766; disscussion 767. |

| 2. | Lacy AM, García-Valdecasas JC, Delgado S, Castells A, Taurá P, Piqué JM, Visa J. Laparoscopy-assisted colectomy versus open colectomy for treatment of non-metastatic colon cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:2224-2229. |

| 3. | Leung KL, Kwok SP, Lam SC, Lee JF, Yiu RY, Ng SS, Lai PB, Lau WY. Laparoscopic resection of rectosigmoid carcinoma: prospective randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;363:1187-1192. |

| 4. | A comparison of laparoscopically assisted and open colectomy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2050-2059. |

| 5. | Braga M, Vignali A, Zuliani W, Radaelli G, Gianotti L, Toussoun G, Carlo V. Training period in laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:31-35. |

| 6. | Braga M, Frasson M, Zuliani W, Vignali A, Pecorelli N, Di Carlo V. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open left colonic resection. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1180-1186. |

| 7. | Taylor GW, Jayne DG, Brown SR, Thorpe H, Brown JM, Dewberry SC, Parker MC, Guillou PJ. Adhesions and incisional hernias following laparoscopic versus open surgery for colorectal cancer in the CLASICC trial. Br J Surg. 2010;97:70-78. |

| 8. | Duepree HJ, Senagore AJ, Delaney CP, Fazio VW. Does means of access affect the incidence of small bowel obstruction and ventral hernia after bowel resection? Laparoscopy versus laparotomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197:177-1781. |

| 9. | Bergamaschi R, Pessaux P, Arnaud JP. Comparison of conventional and laparoscopic ileocolic resection for Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1129-1133. |

| 10. | Bonjer HJ, Hop WC, Nelson H, Sargent DJ, Lacy AM, Castells A, Guillou PJ, Thorpe H, Brown J, Delgado S. Laparoscopically assisted vs open colectomy for colon cancer: a meta-analysis. Arch Surg. 2007;142:298-303. |

| 11. | Jackson TD, Kaplan GG, Arena G, Page JH, Rogers SO Jr. Laparoscopic versus open resection for colorectal cancer: a metaanalysis of oncologic outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:439-446. |

| 12. | Berends FJ, Kazemier G, Bonjer HJ, Lange JF. Subcutaneous metastases after lapar oscopic colectomy. Lancet. 1994;344:58. |

| 13. | Wexner SD, Cohen SM. Port site metastases after laparoscopic colorectal surgery for cure of malignancy. Br J Surg. 1995;82:295-298. |

| 14. | Nduka CC, Darzi A. Port-site metastasis in patients undergoing laparoscopy for gastrointestinal malignancy. Br J Surg. 1997;84:583. |

| 15. | Brundell SM, Tucker K, Texler M, Brown B, Chatterton B, Hewett PJ. Variables in the spread of tumor cells to trocars and port sites during operative laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:1413-1419. |

| 16. | Balli JE, Franklin ME, Almeida JA, Glass JL, Diaz JA, Reymond M. How to prevent port-site metastases in laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:1034-1036. |

| 17. | Hackert T, Uhl W, Bchler MW. Specimen retrieval in laparoscopic colon surgery. Dig Surg. 2002;19:502-506. |

| 18. | Buunen M, Veldkamp R, Hop WC, Kuhry E, Jeekel J, Haglind E, Påhlman L, Cuesta MA, Msika S, Morino M. Survival after laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for colon cancer: long-term outcome of a randomised clinical trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:44-52. |

| 19. | Fleshman J, Sargent DJ, Green E, Anvari M, Stryker SJ, Beart RW Jr, Hellinger M, Flanagan R Jr, Peters W, Nelson H. Laparoscopic colectomy for cancer is not inferior to open surgery based on 5-year data from the COST Study Group trial. Ann Surg. 2007;246:655-662; discussion 662-664. |

| 20. | Lacy AM, Delgado S, Castells A, Prins HA, Arroyo V, Ibarzabal A, Pique JM. The long-term results of a randomized clinical trial of laparoscopy-assisted versus open surgery for colon cancer. Ann Surg. 2008;248:1-7. |

| 21. | Wichmann MW, Hüttl TP, Winter H, Spelsberg F, Angele MK, Heiss MM, Jauch KW. Immunological effects of laparoscopic vs open colorectal surgery: a prospective clinical study. Arch Surg. 2005;140:692-697. |

| 22. | Takeuchi I, Ishida H, Mori T, Hashimoto D. Comparison of the effects of gasless procedure, CO2-pneumoperitoneum, and laparotomy on splenic and hepatic natural killer activity in a rat model. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:255-260. |