Published online Mar 15, 2024. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v16.i3.653

Peer-review started: December 21, 2023

First decision: January 10, 2024

Revised: January 15, 2024

Accepted: February 6, 2024

Article in press: February 6, 2024

Published online: March 15, 2024

Processing time: 82 Days and 1.6 Hours

Pylorus-preserving gastrectomy (PPG) has been widely accepted as a function-preserving gastrectomy for middle-third early gastric cancer (EGC) with a distal tumor border at least 4 cm proximal to the pylorus. The procedure essentially preserves the function of the pyloric sphincter, which requires to preserve the upper third of the stomach and a pyloric cuff at least 2.5 cm. The suprapyloric and infrapyloric vessels are usually preserved, as are the hepatic and pyloric branches of the vagus nerve. Compared with distal gastrectomy, PPG has significant advantages in preventing dumping syndrome, body weight loss and bile reflux gastritis. The postoperative complications after PPG have reached an acceptable level. PPG can be considered a safe, effective, and superior choice in EGC, and is expected to be extensively performed in the future.

Core Tip: Pylorus-preserving gastrectomy (PPG) has been widely accepted as a function-preserving gastrectomy for middle-third early gastric cancer. The procedure requires to preserve the upper third of the stomach and a pyloric cuff at least 2.5 cm. The hepatic and pyloric branches of the vagus nerve are usually preserved. PPG has significant advantages in preventing dumping syndrome, body weight loss and bile reflux gastritis.

- Citation: Sun KK, Wu YY. Pylorus-preserving gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2024; 16(3): 653-658

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v16/i3/653.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v16.i3.653

Pylorus-preserving gastrectomy (PPG) was initially proposed for treating gastric ulcers in 1967[1]. It has since been regularly performed as a function-preserving gastrectomy for early gastric cancer (EGC) in Japan and South Korea[2], which embodies the pursuit of "precision medicine". In its development over 60 years, PPG has gradually reached a consensus on lymph node dissection, the length of the pyloric cuff, and preservation of the vagus nerve and pyloric vessels. PPG is acceptable with favorable outcomes for the middle portion EGC. This article reviewed the development history, indications, oncological safety, complications, and functional benefits of PPG.

As early as the end of the 19th century, surgeons have tried to perform gastrectomy with the preservation of the gastric antrum and pylorus to reduce the complications of bile gastric reflux and dumping syndrome. Segmental gastrectomy (SG) was first reported in gastric ulcers treatment in 1897[3]. However, SG was abandoned in the 1920s because of postoperative complications such as anastomotic stenosis, ulcer recurrence, and delayed gastric emptying (DGE)[4,5]. Subsequently, Wangensteen[6] recommended the supplementing pyloroplasty to promote gastric drainage, but this exactly offset the merits of preserving the pylorus. Maki et al[1] first described the detailed surgical procedures of PPG in 1967, and reported long-term satisfactory results in gastric ulcer treatment in 1992[7]. However, the development of internal medicine has greatly changed the therapeutic strategy of peptic ulcer, and PPG has gradually faded out of gastric ulcers treatment. In 1991, Kodama and Koyama[8] first proposed PPG for treating EGC. At this late hour, PPG has been recommended as a treatment route for middle-third EGC with a distal tumor border at least 4 cm proximal to the pylorus[9]. Nunobe et al[10] reported that to retain the functions of the gastric antrum and pylorus, the length of the preserved gastric antrum should be at least 2.5 cm. Since most T1aN0M0 cases undergo endoscopic mucosal resection, the indications of PPG are mainly T1aN0M0 cases which are not suitable for endoscopic resection and T1bN0M0 cases. It can also be considered as an additive surgery after endoscopic resection[9].

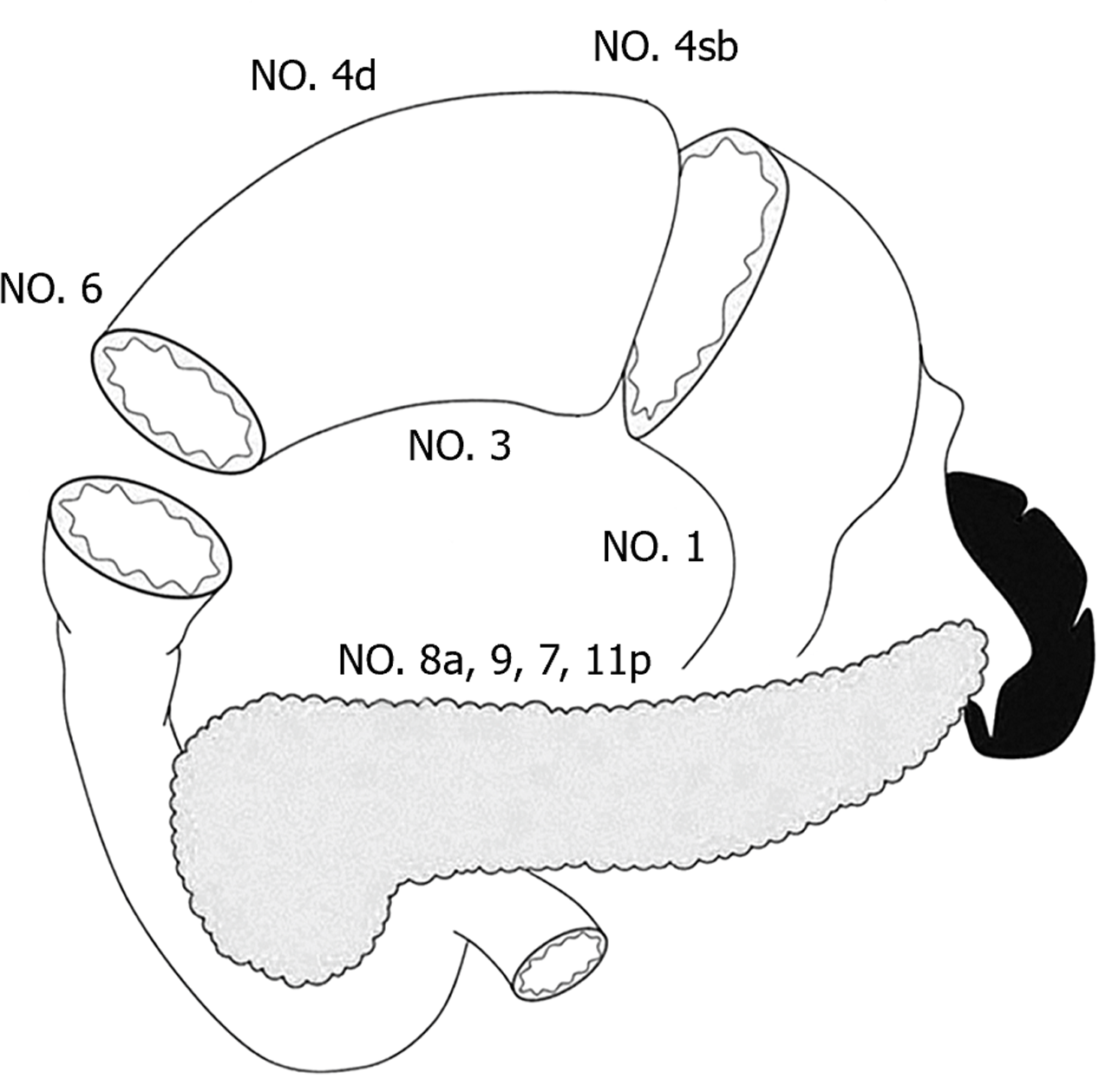

Preservation of pyloric function during PPG procedure depends on the pyloric antrum blood flow and nerve preservation, which result in the incomplete dissection of No. 5 and No. 6 lymph nodes. In recent years, the regularity of lymph node metastasis with the middle portion EGC has provided a theoretical basis for PPG. In 1991, Kodama and Koyama[8] investigated the lymphatic drainage pathways in middle-third gastric cancer by the subserosal injection of activated carbon particles on the lesser and greater curvatures of the stomach. The results showed that the lymph flowed mostly from the lesser curvature to the No. 3 and No. 7 lymph nodes, with few drainaging to the No. 5 nodes, while drainage from the greater curvature included the No. 4d and No. 6 lymph nodes. 154 patients undergoing subtotal gastrectomy for middle-third EGC were analyzed and the result showed no involvement of the No. 5 and No. 6 lymph nodes in 82 cases with mucosal invasion, while No. 6 node involvement was only confirmed in 4.2% (3/72) patients with submucosal invasion. Another cohort study of 701 cases found metastasis rates of 0% and 0.4% for the No. 5 and No. 6 nodes, respectively, and involvement of No. 12a and No. 11p was negligible in middle-body EGC[11]. Therefore, the authors proposed that PPG is safe for middle-third EGC, as well as for high and moderately differentiated T2 gastric cancer below 4 cm in diameter. In 2013, Shinohara et al[12] investigated the embryology and topographic anatomy of the infrapyloric lymph region and divided No. 6 lymph nodes into 3 subgroups, namely 6a, 6v and 6i. No. 6a is separated from No. 6i by the infrapyloric artery and the initial branch of the right gastroepiploic artery. The involvement No. 6i lymph node is extremely rare, which provides an important theoretical basis for selective dissection of No. 6 lymph nodes in PPG. Similarly, to retain the hepatic and pyloric branches of the vagus nerve, No. 5 and No. 12a lymph nodes are routinely preserved. Additionally, metastasis to the left suprapancreatic lymph nodes is extremely rare, so that dissection of the No. 11p node is not required in PPG. Therefore, the dissection of No. 1, 3, 4sb, 4d, 6a, 6v, 7, 8a, 9 lymph nodes is required in PPG procedure (Figure 1)[9].

Both extracorporeal and intracorporeal anastomosis can be performed in PPG. The extracorporeal anastomosis was attached from the middle incision in the upper abdomen with the anastomosis site lying directly beneath[13,14]. This allowed the surgeons to palpate the margin before transection of the stomach, avoiding insufficient resection margin or excessive resection. The handsewn anastomosis can be intermittent or continuous suture, and a continuous suture does not increase the risk of anastomotic stenosis. More recently, total laparoscopic gastrectomy was gradually performed, and there are many methods for intracorporeal anastomosis[15]. Yang et al[16] performed a layer-to-layer manual anastomosis of the anterior and posterior walls using two double-needle barbed sutures intracorporeal. Alternatively, suture of the posterior side with a linear stapler and handsewn suture on the front side was performed. Intracorporeal delta-shaped gastrogastrostomy with a linear stapler was a relatively simple method during laparoscopic PPG, but it requires the sacrifice of part of the gastric antrum. Additionally, the antrum and proximal remnant stomach twist partially around the anastomosis, and the lesser curvature side was not used for anastomosis[15]. A retrospective analysis showed no significant difference in proximal margin, the number of lymph nodes, surgical complication and postoperative hospital stay between intracorporeal and extracorporeal anastomosis[17]. Ohashi et al[18] reported the “piercing method” to perform intracorporeal end-to-end anastomosis with a linear stapler, but this method is cumbersome and time-consuming. Similarly, overlap anastomosis also requires the sacrifice of a certain length of the gastric antrum. In

The concerns surrounding the oncological safety of PPG come from two aspects: The limited dissection of the No. 5 and No. 6i lymph nodes and the resection margins of the stomach. Since PPG meets the requirement of a 2-cm margin, and the frozen section diagnosis can also determine the tumor resection margin during the operation. Therefore, the concerns mainly come from incomplete lymph node dissection. According to a database of 305 patients with middle-third EGC, the rate of No. 5 lymph node metastasis was 0.2%; meanwhile, a 98% overall 5-year survival and 0% cancer-specific mortality was reported after PPG[19]. Jiang et al[14] reported an overall 3-year survival rate of 97.8 % and disease-specific 3-year survival rate of 99.3 % in 188 patients received PPG. These results were consistent with previous reports on the mortality after distal gastrectomy (DG) for EGC. A multicenter cohort analysis involving 1004 EGC patients (502 PPG and 502 DG) showed that the 5-year overall survival rate was 98.4% for PPG and 96.6% for DG, and no significant differences in either overall survival or relapse-free survival between the two groups[20]. Another systematic review evaluated the pathological and oncological outcomes between PPG and DG in 4500 EGC patients. The results showed fewer lymph nodes harvested, shorter proximal and distal margins in the PPG group, and there was no significant difference in overall survival or relapse-free survival[21]. Thus, the oncological safety of PPG was comparable to that of DG in EGC patients. In addition, due to the accuracy of preoperative staging, some patients with preoperative diagnosis of T1 showed T2 or deeper invasion[22]. Whether such patients require additive surgery is another question to be concerned. Takahashi et al[23] reported that 6.4% of the patients had postoperative pT2 or deeper after PPG in 897 patients; nevertheless, no higher recurrence rate was observed in these patients. It has been reported that patients with a preoperative staging of T1 but postoperative pT2 had a better prognosis and less occurrence of lymph node metastases in comparison with patients preoperatively diagnosed as T2[24]. Although several retrospective studies have reported acceptable long-term survival outcomes for PPG[14,19,20,25,26], it has not been confirmed by prospective clinical studies. It is hoped that the ongoing multicenter randomized controlled trial KLASS-04 will settle the question of the advantages of PPG to DG in terms of oncological safety and functional benefits.

The core technology of PPG is the functional preservation of the pylorus, and it can theoretically prevent postoperative dumping syndrome and alkaline reflux. Recent studies have shown that compared with DG, PPG can maintain body weight and better postoperative nutritional status[25,27,28]. Terayama et al[29] compared postoperative skeletal muscle index between PPG and DG in in old EGC patients, and the result showed a great advantage in maintaining the postoperative skeletal muscle mass after PPG. Moreover, the retention of the hepatic branches could also reduce the occurrence of cholestasis and gallbladder stones. Nevertheless, PPG is also associated with non-negligible postoperative complications, namely DGE, gastric stasis or gastroparesis. Therefore, to benefit patients with PPG, it is necessary to understand the mechanisms responsible for postoperative DGE and find the preventive methods. It is acknowledged that the normal pyloric function is largely dependent on the length of the pyloric cuff, together with the retention of circulation and nerve supply to the pyloric antrum. In the early years of PPG, surgeons focused on the retention of the vagus nerve and, at that time, the preservation of the pyloric and hepatic branches was strictly required. With the continuous deepening of research, people realized that the blood flow of the pyloric cuff was another important factor in the functional preservation of the pylorus. Kiyokawa et al[30] found that the preservation the infrapyloric vein significantly reduced the incidence of DGE after PPG, which may be effective to reduce pyloric edema. The appropriate length of the pyloric cuff is another important factor affecting postoperative complications. Nakane et al[31] demonstrated that 2.5 cm was superior in terms of some postoperative complications and weight recovery compared with 1.5 cm. However, Morita et al[32] found that the occurrence of gastric stasis did not differ between cuff length 3.0 cm and over 3.0 cm. The Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Study after PPG revealed that the dimensions of the proximal gastric remnant and hand-sewn anastomosis also played a significant part in postoperative symptoms and quality of life[33]. In terms of patient eligibility, a retrospective study found that age (≥ 61 years), diabetes, and postoperative intra-abdominal infection were risk factors for DGE[23]. High body mass index was identified as another risk factor for gastric stasis after PPG[22]. The patients with the presence of hiatal hernia and dietary complications would predispose to reflux esophagitis after PPG[34,35].

PPG has been widely accepted as a function-preserving gastrectomy for middle-third EGC. Compared with DG, PPG has significant advantages in preventing dumping syndrome, body weight loss and bile reflux gastritis. The postoperative complications after PPG have reached an acceptable level. The preservation of pyloric function has complicated the technicalities of PPG and suggested the potential risks associated with incomplete lymph node dissection. The precise determination of functional benefits, oncological safety, technique standardization and the clarification of complications have not been strictly addressed. It is also not fully understood whether patients benefit from PPG if they suffer gastric stasis, or whether PPG for EGC increases the risk of secondary gastric cancer.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ergenç M, Turkey S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: A P-Editor: Cai YX

| 1. | Maki T, Shiratori T, Hatafuku T, Sugawara K. Pylorus-preserving gastrectomy as an improved operation for gastric ulcer. Surgery. 1967;61:838-845. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Kosuga T, Tsujiura M, Nakashima S, Masuyama M, Otsuji E. Current status of function-preserving gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2021;5:278-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Mikulicz-Radecki J. Die chirurgische Behandlung des chronischen Magengeschwurs. Verhandl Deutsch Gesselsch Chir. 1897;26:31. |

| 4. | Barber WH. Annular Segmental Gastrectomy. Ann Surg. 1917;66:672-678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fujimura T, Fushida S, Kayahara M, Ohta T, Kinami S, Miwa K. Transectional gastrectomy: an old but renewed concept for early gastric cancer. Surg Today. 2010;40:398-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wangensteen OH. Segmental gastric resection: an acceptable operation for peptic ulcer; tubular resection unacceptable. Surgery. 1957;41:686-690. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Sasaki I, Fukushima K, Naito H, Matsuno S, Shiratori T, Maki T. Long-term results of pylorus-preserving gastrectomy for gastric ulcer. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1992;168:539-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kodama M, Koyama K. Indications for pylorus preserving gastrectomy for early gastric cancer located in the middle third of the stomach. World J Surg. 1991;15:628-33; discussion 633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2018 (5th edition). Gastric Cancer. 2021;24:1-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 735] [Cited by in RCA: 1336] [Article Influence: 334.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 10. | Nunobe S, Hiki N, Fukunaga T, Tokunaga M, Ohyama S, Seto Y, Yamaguchi T. Laparoscopy-assisted pylorus-preserving gastrectomy: preservation of vagus nerve and infrapyloric blood flow induces less stasis. World J Surg. 2007;31:2335-2340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Khalayleh H, Kim YW, Yoon HM, Ryu KW. Assessment of Lymph Node Metastasis in Patients With Gastric Cancer to Identify Those Suitable for Middle Segmental Gastrectomy. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e211840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Shinohara H, Kurahashi Y, Kanaya S, Haruta S, Ueno M, Udagawa H, Sakai Y. Topographic anatomy and laparoscopic technique for dissection of no. 6 infrapyloric lymph nodes in gastric cancer surgery. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16:615-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hiki N, Kaminishi M. Pylorus-preserving gastrectomy in gastric cancer surgery--open and laparoscopic approaches. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2005;390:442-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jiang X, Hiki N, Nunobe S, Fukunaga T, Kumagai K, Nohara K, Sano T, Yamaguchi T. Postoperative outcomes and complications after laparoscopy-assisted pylorus-preserving gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Ann Surg. 2011;253:928-933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Kumagai K, Hiki N, Nunobe S, Sekikawa S, Chiba T, Kiyokawa T, Jiang X, Tanimura S, Sano T, Yamaguchi T. Totally laparoscopic pylorus-preserving gastrectomy for early gastric cancer in the middle stomach: technical report and surgical outcomes. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:183-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Yang J, Xie J, Xu L, Yin Y, Lao X, Yan Z. Clinical Experience of Intracorporeal Hand-sewn Anastomosis Following Totally Laparoscopic Pylorus-Preserving Gastrectomy for Middle-Third Early Gastric Cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2022;26:659-661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Alzahrani K, Park JH, Lee HJ, Park SH, Choi JH, Wang C, Alzahrani F, Suh YS, Kong SH, Park DJ, Yang HK. Short-term Outcomes of Pylorus-Preserving Gastrectomy for Early Gastric Cancer: Comparison Between Extracorporeal and Intracorporeal Gastrogastrostomy. J Gastric Cancer. 2022;22:135-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Ohashi M, Hiki N, Ida S, Kumagai K, Nunobe S, Sano T. A novel method of intracorporeal end-to-end gastrogastrostomy in laparoscopic pylorus-preserving gastrectomy for early gastric cancer, including a unique anastomotic technique: piercing the stomach with a linear stapler. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:4337-4343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Hiki N, Sano T, Fukunaga T, Ohyama S, Tokunaga M, Yamaguchi T. Survival benefit of pylorus-preserving gastrectomy in early gastric cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209:297-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Aizawa M, Honda M, Hiki N, Kinoshita T, Yabusaki H, Nunobe S, Shibasaki H, Matsuki A, Watanabe M, Abe T. Oncological outcomes of function-preserving gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: a multicenter propensity score matched cohort analysis comparing pylorus-preserving gastrectomy versus conventional distal gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:709-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Hou S, Liu F, Gao Z, Ye Y. Pathological and oncological outcomes of pylorus-preserving versus conventional distal gastrectomy in early gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2022;20:308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Park DJ, Kim YW, Yang HK, Ryu KW, Han SU, Kim HH, Hyung WJ, Park JH, Suh YS, Kwon OK, Yoon HM, Kim W, Park YK, Kong SH, Ahn SH, Lee HJ. Short-term outcomes of a multicentre randomized clinical trial comparing laparoscopic pylorus-preserving gastrectomy with laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer (the KLASS-04 trial). Br J Surg. 2021;108:1043-1049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Takahashi R, Ohashi M, Hiki N, Makuuchi R, Ida S, Kumagai K, Sano T, Nunobe S. Risk factors and prognosis of gastric stasis, a crucial problem after laparoscopic pylorus-preserving gastrectomy for early middle-third gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2020;23:707-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Tokunaga M, Hiki N, Fukunaga T, Ohyama S, Yamada K, Yamaguchi T. Better prognosis of T2 gastric cancer with preoperative diagnosis of early gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1514-1519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tsujiura M, Hiki N, Ohashi M, Nunobe S, Kumagai K, Ida S, Hayami M, Sano T, Yamaguchi T. Excellent Long-Term Prognosis and Favorable Postoperative Nutritional Status After Laparoscopic Pylorus-Preserving Gastrectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:2233-2240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 26. | Morita S, Katai H, Saka M, Fukagawa T, Sano T, Sasako M. Outcome of pylorus-preserving gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2008;95:1131-1135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Eom BW, Park B, Yoon HM, Ryu KW, Kim YW. Laparoscopy-assisted pylorus-preserving gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: A retrospective study of long-term functional outcomes and quality of life. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:5494-5504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 28. | Suh YS, Han DS, Kong SH, Kwon S, Shin CI, Kim WH, Kim HH, Lee HJ, Yang HK. Laparoscopy-assisted pylorus-preserving gastrectomy is better than laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for middle-third early gastric cancer. Ann Surg. 2014;259:485-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 29. | Terayama M, Ohashi M, Makuuchi R, Hayami M, Ida S, Kumagai K, Sano T, Nunobe S. A continuous muscle-sparing advantage of pylorus-preserving gastrectomy for older patients with cT1N0M0 gastric cancer in the middle third of the stomach. Gastric Cancer. 2023;26:145-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kiyokawa T, Hiki N, Nunobe S, Honda M, Ohashi M, Sano T. Preserving infrapyloric vein reduces postoperative gastric stasis after laparoscopic pylorus-preserving gastrectomy. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2017;402:49-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 31. | Nakane Y, Michiura T, Inoue K, Sato M, Nakai K, Yamamichi K. Length of the antral segment in pylorus-preserving gastrectomy. Br J Surg. 2002;89:220-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Morita S, Sasako M, Saka M, Fukagawa T, Sano T, Katai H. Correlation between the length of the pyloric cuff and postoperative evaluation after pylorus-preserving gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. 2010;13:109-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Namikawa T, Hiki N, Kinami S, Okabe H, Urushihara T, Kawahira H, Fukushima N, Kodera Y, Yumiba T, Oshio A, Nakada K. Factors that minimize postgastrectomy symptoms following pylorus-preserving gastrectomy: assessment using a newly developed scale (PGSAS-45). Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:397-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 34. | Nunobe S, Hiki N. Function-preserving surgery for gastric cancer: current status and future perspectives. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Otake R, Kumagai K, Ohashi M, Makuuchi R, Ida S, Sano T, Nunobe S. Reflux Esophagitis After Laparoscopic Pylorus-Preserving Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2023;30:2294-2303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |