Published online Sep 15, 2023. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v15.i9.1653

Peer-review started: May 29, 2023

First decision: July 23, 2023

Revised: July 31, 2023

Accepted: August 15, 2023

Article in press: August 15, 2023

Published online: September 15, 2023

Processing time: 106 Days and 20.1 Hours

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains a relevant public health problem. Current research suggests that racial, economic and geographic disparities impact access. Despite the expansion of Medicaid eligibility as a key component of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), there is a dearth of information on the utilization of newly gained access to CRC screening by low-income individuals. This study investigates the impact of the ACA’s Medicaid expansion on utilization of the various CRC screening modalities by low-income participants. Our working hypothesis is that Medicaid expansion will increase access and utilization of CRC screening by low-income participants.

To investigate the impact of the Affordable Care Act and in particular the effect of Medicaid expansion on access and utilization of CRC screening modalities by Medicaid state expansion status across the United States.

This was a quasi-experimental study design using data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, a large health system survey for participants across the United States and with over 2.8 million responses. The period of the study was from 2011 to 2016 which was dichotomized as pre-ACA Medicaid expansion (2011-2013) and post-ACA Medicaid expansion (2014-2016). The change in utilization of access to CRC screening strategies between the expansion periods were analyzed as the dependent variables. Secondary analyses included stratification of the access by ethnicity/race, income, and education status.

A greater increase in utilization of access to CRC screening was observed in Medicaid expansion states than in non-expansion states [+2.9%; 95% confidence interval (95%CI): 2.12, 3.69]. Low-income participants showed a +4.02% (95%CI: 2.96, 5.07) change between the expansion periods compared with higher income groups +3.19% (1.70, 4.67). Non-Hispanic Whites and Hispanics [+3.01% (95%CI: 2.16, 3.85) vs +5.51% (95%CI: 2.81, 8.20)] showed a statistically significant increase in utilization of access but not in Non-Hispanic Blacks, or Multiracial. There was an increase in utilization across all educational levels. This was significant among those who reported having a high school graduate degree or more +4.26 % (95%CI: 3.16, 5.35) compared to some high school or less +1.59% (95%CI: -1.37, 4.55).

Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act led to an overall increase in self-reported use of CRC screening tests by adults aged 50-64 years in the United States. This finding was consistent across all low-income populations, but not all races or levels of education.

Core Tip: While many researchers have shown and studied how the Affordable Care Act through its Medicaid’s expansion increased healthcare access to different categories of potential beneficiaries, little is known about actual utilization of this “newly gained” access. Our paper focuses specifically on examining this specific question.

- Citation: Fletcher G, Culpepper-Morgan J, Genao A, Alatevi E. Utilization of access to colorectal cancer screening modalities in low-income populations after medicaid expansion. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2023; 15(9): 1653-1661

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v15/i9/1653.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v15.i9.1653

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains a relevant public health problem in the United States being the second leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States and the third most common cancer in men and in women[1]. The screening guidelines based on the 2016 recommendations by the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) for adults aged 50-75 years included one of three modalities: An annual high-sensitivity fecal occult blood test (FOBT), sig

Despite these recommendations, there are wide disparities in CRC screening rates where only 61% of adults in the 50-75-year group report recent CRC screening[1]. Racial and geographic disparities impact access to screening and cancer-related outcomes. The incidence of and mortality from CRC is higher for Blacks than for Whites as well as for lower-income populations than for higher-income groups[2,3]. Several barriers to equitable access to screening have been identified including affordability, a lack of a doctor’s recommendation for screening, as well as a lack of a usual care primary care provider.

A key component of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was an expansion of Medicaid eligibility to adults earning up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL). To support this expanded coverage, effective January 1, 2014, states would receive 100 percent federal funding for the first 3 years phasing to 90 percent federal funding in subsequent years[4-6]. Although this provision was originally intended to be enacted in all states, a United States Supreme Court decision gave states the option not to adopt it[7,8]. As of August 2018, only 34 states including the District of Columbia had expanded Medicaid[7]. Furthermore, under the ACA, private health plans are required to cover a range of preventive services including cancer screening at no cost to beneficiaries and at intervals defined by the USPSTF.

While elements of the ACA have remained politically controversial[8], the literature on the ACA and healthcare is growing but remains limited in depth of query[9-15]. On cancers in the United States specifically, recent studies have suggested that the ACA has resulted in an increase in cervical and CRC screening rates and the diagnosis of cancers at an earlier more treatable stage.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the impact of the ACA and in particular the effect of Medicaid expansion on access and utilization of the colorectal screening services by Medicaid state expansion status. The central hypothesis was that the ACA’s Medicaid expansion would reduce healthcare access disparities and thereby increase access to CRC screening services by individuals across all socio-economic strata thereby increasing the likelihood of utilization of the access.

Our study used a quasi-experimental design. Data source was the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) for the period 2011 to 2016. Data from 2011-13 BRFSS was the pre-Medicaid expansion period while that from 2014-2016, post-Medicaid expansion period. BRFSS is an annual state-wide survey of adults aged 18 years and older. Details of the methodology of the survey can be found elsewhere[16]. BRFSS completes more than 400000 adult interviews each year, making it the largest continuously conducted health survey system in the world. Adjusted response rates vary by state and in 2009 ranged between 39% and 67%; unadjusted response rates ranged between 19% and 62%, depending on state and survey year.

Compared to the analysis from previous researchers[14], we used data from all 6 years available. Although ACA was passed into law in 2010, coverage under the Medicaid expansion became effective January 1, 2014, in all states that had adopted the Medicaid expansion. We thus used the period beginning 2014 as the expansion period. At the time of this analysis, the most complete dataset was for the year 2016.

To be included in the study, participants must be adult non-elderly United States citizens, 50-64 years, who took the survey in the years 2011-2016. They also must have completed at least one of the screening modalities and be eligible for Medicaid. Persons who were less than 50 years of age or older than 64 years of age, did not complete a CRC screening modality in the surveyed years were excluded. Although BRFSS reported annual household income in eight categories, in our analysis, we dichotomized this variable into incomes less than $25000 and more than $25000. Our Medicaid eligible population was based on household income adjusted for by household size. This was approximately $25000 per annum, a value used as proxy for Medicaid eligibility, and which corresponded to approximately 138% of the FPL during the period of study.

The treatment variable for this study was Medicaid expansion status. A detailed list of the states by expansion status is available in the references[7]. CRC screening eligibility was based on the 2015 USPSTF recommendations as follows: Eligible for CRC screening if not had a colonoscopy within the past 10 years or a sigmoidoscopy with FOBT within the past 5 years. Participants who had had reported screening using only FOBT were still screen-eligible during the survey year, since FOBT is an annual test.

A difference-in-differences technique was used to analyze the effect of Medicaid expansion status on the utilization of access to colorectal screening. Here, we compared rates of colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, and FOBT among screen eligible adults who responded to the survey. The binary outcome of change in utilization of access to CRC screening strategies pre and post ACA were analyzed as the dependent variables. Other secondary analysis included stratification of the access by ethnicity/race, income, and education status.

Descriptive and demographic variables were analyzed by stratification of the respondents’ socioeconomic characteristics: Self-reported household income, educational attainment, employment status, and race/ethnicity, age, and gender. Educational status was treated as binary characteristic: Whether the respondent had at least graduated from high school or not.

We used the stratification, primary sampling unit and final weight variables through a survey analysis to account for collection design of the BRFSS as recommended by the CDC. The results were generated using SAS software version 9.4.

In total, 2.86 million responses in the BRFSS database were considered during the period of study, 893004 were adults aged between 50 and 64 who had utilized at least one colorectal screening modality. This was considered our “screening cohort”. We used a complete case analysis because less than 1.65% of the data had missing values. There were 179734 respondents included from Medicaid non-expansion states in the pre-ACA era while 285589 were in Medicaid expansion states in the pre-ACA period. In the post-ACA period, 159169 were in Medicaid non-expansion states and 268512 in Medicaid expansion states. In our analysis, 33 states were considered as expansion states during the period of study 2014-2016.

The proportion of individuals across the three age groups (50-54 years, 55-59 years, and 60-64 years) were 39%, 32%, and 27%, respectively across all states in the pre-ACA era while in the post-ACA period, these were 37%, 32%, and 31% respectively. Other demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1.

| All states (n = 893004) | Expansion states (n = 554101) | Non-expansion states (n = 338903) | ||||

| Pre-ACA | Post-ACA | Pre-ACA | Post-ACA | Pre-ACA | Post-ACA | |

| Age (yr) | ||||||

| 50-54 | 144633 (39.15) | 125057 (36.68) | 89366 (39.16) | 78752 (36.63) | 55267 (39.13) | 46305 (36.78) |

| 55-59 | 158010 (31.18) | 145440 (31.86) | 97145 (31.49) | 91564 (32.07) | 60865 (30.61) | 53876 (31.48) |

| 60-64 | 162680 (29.67) | 157184 (31.46) | 99078 (29.35) | 98196 (31.30) | 63602 (30.25) | 58988 (31.74) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 189909 (48.59) | 183869 (48.49) | 117729 (48.72) | 116204 (48.69) | 72180 (48.35) | 67665 (48.13) |

| Race | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 367535 (70.94) | 335133 (69.10) | 227986 (72.30) | 212968 (70.46) | 139549 (68.47) | 122165 (66.67) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 40005 (11.05) | 35498 (11.80) | 21748 (9.64) | 19925 (10.17) | 18257 (13.64) | 15573 (14.73) |

| Other non-Hispanic | 17151 (4.95) | 16381 (5.23) | 11524 (6.16) | 11230 (6.60) | 5627 (2.73) | 5151 (2.78) |

| Multiracial non-Hispanic | 8075 (1.25) | 7433 (1.14) | 5445 (1.36) | 5174 (1.22) | 2630 (1.05) | 2259 (1.01) |

| Hispanic | 26999 (11.80) | 27038 (12.73) | 15400 (10.54) | 15079 (11.56) | 11599 (14.11) | 11959 (14.82) |

| Income | ||||||

| < $25000 | 108872 (26.91) | 90810 (26.19) | 62264 (24.56) | 53270 (24.04) | 46608 (31.27) | 37540 (30.07) |

| Employment status | ||||||

| Employed for wages | 229742 (49.78) | 214339 (50.54) | 143761 (51.16) | 137816 (52.12) | 85981 (47.27) | 76523 (47.70) |

| Self-employed | 51031 (10.74) | 48916 (11.28) | 31149 (10.79) | 30137 (11.23) | 19882 (10.65) | 18779 (11.37) |

| Out of work > 1 yr | 19335 (5.04) | 13208 (3.67) | 12399 (5.18) | 8569 (3.70) | 6936 (4.79) | 4639 (3.62) |

| Out of work < 1 yr | 12272 (3.12) | 9159 (2.50) | 7854 (3.19) | 6055 (2.60) | 4418 (3.01) | 3104 (2.33) |

| Homemaker | 22567 (5.44) | 20059 (5.82) | 12528 (4.99) | 11537 (5.22) | 10039 (6.26) | 8522 (6.06) |

| Student | 1248 (0.28) | 1022 (0.24) | 788 (0.28) | 692 (0.25) | 460 (0.28) | 330 (0.12) |

| Retired | 67400 (12.91) | 60896 (12.66) | 41744 (12.83) | 37970 (12.43) | 25656 (13.05) | 22926 (13.07) |

| Unable to work | 59643 (12.69) | 56912 (13.61) | 33900 (11.58) | 33669 (12.46) | 25743 (14.70) | 23243 (15.65) |

| Education | ||||||

| Some high school or less | 32774 (13.35) | 28992 (13.71) | 18155 (15.34) | 16686 (12.80) | 14619 (15.23) | 12306 (12.32) |

| At least a high school graduate | 431169 (86.65) | 397159 (86.29) | 266416 (84.66) | 250815 (87.20) | 164753 (84.77) | 146344 (87.68) |

Responses to the type of screening modality used by adults aged 50-64 years is shown in Table 2. All 893004 eligible adults had had at least one type of CRC screening done. Out of this number, screening with colonoscopy was reported by 838694, sigmoidoscopy 41459 and FOBT 467428 which corresponded to weighted percentages as follows: 62% had at least a colonoscopy, 35% had had a sigmoidoscopy and 3% a fecal occult blood test. A summary of responses to the type of screening completed during the period of study in our screening cohort is shown in Table 2.

| Screening modality | Percentage point change | Difference-in- difference estimate | P value | |

| Expansion states | Non-expansion states | |||

| Colonoscopy | 16.88 (16.44, 17.32) | 14.49 (13.87, 15.11) | 2.40 (1.64, 3.15) | < 0.001 |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 0.31 (0.20, 0.44) | 0.15 (0.001, 0.280) | 0.17 (-0.01, 0.35) | 0.060 |

| FOBT | 2.52 (2.28, 2.76) | 1.64 (1.35, 1.94) | 0.88 (0.50, 1.26) | < 0.001 |

| CRC screen | 18.34 (17.89, 18.80) | 15.44 (14.80, 16.08) | 2.90 (2.12, 3.69) | < 0.001 |

In general, while there was an overall increase in utilization of access to CRC screening reported across all states, the rate of increase was significantly greater in expansion states than non-expansion states [+2.9%; 95% confidence interval (95%CI): 2.12, 3.69]. Amongst the three screening modalities only colonoscopy and FOBT were significant statistically when utilization in expansion states were compared to non-expansion states. Utilization of colonoscopies increased by 2.4% (95%CI: 1.64, 3.15) in the Medicaid expansion states while that for FOBT increased by 0.88% (95%CI: 0.50, 1.26).

Table 3 shows a difference-in-difference analysis of expansion vs non-expansion states by income level using $25000 as a proxy for Medicaid eligibility. Across all income levels, the effect of Medicaid expansion due to ACA was statistically significant when the pre-ACA and post-ACA eras were compared. Low-income participants with incomes < $25000, showed a 4.02% (95%CI: 2.96, 5.07) change between the pre-ACA and post-ACA periods while higher income groups had a difference of 3.19% (95%CI: 1.70, 4.67) because of Medicaid expansion.

| Annual income | Percentage point change | Difference-in-difference estimate | ||

| Expansion states | Non-expansion states | % | 95%CI | |

| < $25000 | 18.94 | 14.92 | 4.02 | (2.96, 5.07) |

| > $25000 | 19.84 | 16.65 | 3.19 | (1.70, 4.67) |

Utilization of access to screening by Medicaid eligible respondents was stratified by race/ethnicity and education (Table 4). There was a statistically significant increase in utilization of access to screening in Non-Hispanic Whites and Hispanics. This translated to 3.01% (95%CI: 2.16, 3.85) in Non-Hispanic Whites and 5.51% (95%CI: 2.81, 8.20) in Hispanics. This difference was however not significant statistically in Non-Hispanic Blacks, Non-Hispanic multiracial and others.

| Race/ethnicity | Percentage point change | Difference-in- difference estimate | ||

| Expansion states | Non-expansion states | % | 95%CI | |

| 1Non-Hispanic White | 19.92 | 16.91 | 3.01 | (2.16, 3.85) |

| 1Hispanic | 13.74 | 8.23 | 5.51 | (2.81, 8.20) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 18.32 | 16.60 | 1.72 | (-0.83, 4.26) |

| Non-Hispanic multiracial | 17.34 | 13.20 | 4.15 | (-2.93, 11.22) |

| Other | 12.39 | 13.93 | -1.54 | (-6.84, 3.76) |

| Education level | ||||

| Some high school or less | 14.63 | 13.42 | 1.59 | (-1.37, 4.55) |

| 1High school grad or more | 18.83 | 15.77 | 4.26 | (3.16, 5.35) |

Table 4 also summarizes utilization of access to screening in the Medicaid eligibility population stratified by education status. While there was an increase in access across all educational levels, it was only statistically significant in the population who reported having high school graduate or more+4.26 % (95%CI: 3.16, 5.35) compared to some high school or less 1.59% (95%CI: -1.37, 4.55).

In our analysis, self-reported utilization of CRC screening modalities according to 2015 USPSTF by adults aged 50-64 years increased more for residents of Medicaid expansion states than for those in non-expansion states (Table 2). The increased uptake of colonoscopy was double that of FOBT. The increased uptake of flexible sigmoidoscopy was minimal and failed to reach statistical significance. With the increased access to health care provided by the ACA, colonoscopy remains the preferred screening strategy. The change in screening rates was consistent across both low and high-income residents in states that expanded Medicaid compared to non-expansion states but this was inconsistent across Race/Ethnicity and education status. Across different races and ethnic groups, Non-Hispanic Whites and Hispanics, from our analysis, were positively impacted by Medicaid expansion while there was no statistically significant difference in colo-rectal screening rates for Non-Hispanic Blacks, Multiracial groups, and others. Lastly, a subgroup analysis of low income (< $25000/year) subjects revealed that education status was significantly associated with uptake of CRC screening in expansion states over non-expansion states.

Our study was designed to determine the impact of the ACA Medicaid expansion on the access to and utilization of CRC screening modalities. We presented our preliminary analysis in 2019 at an international conference[18]. Other studies have used the BRFSS database to explore aspects of our study question. In 2018, Hendryx and Luo examined the effect of ACA expansion on screening for cervical, breast, and colon cancers. They concluded that the ACA increased screening for cervical and colon but not for breast cancer in low-income adults. Their analysis used $20000 as an income cutoff instead of $25000 and excluded households with dependent children. They also limited colonoscopies to the last 2 years of ACA expansion. Because of these study design choices especially limiting their analysis to low-income adults only, we believe that they may have under-estimated the effect of the ACA on uptake of CRC screening due to loss of power from a smaller sample size.

It is reasonable to expect that increased access to care through Medicaid expansion would result in cancers diagnosed at an earlier stage. Han et al[17], examined cancer registry data in expansion and non-expansion states comparing the percentage of uninsured with a diagnosis of cancer from 2010-2013 to the percentage in the first year of expansion 2014. They found the greatest decrease in the number of uninsured new cancer diagnoses among low-income patients in the expansion states. As a secondary outcome they evaluated the increase in early-stage cancer diagnosis. Overall, there was a small (0.4%) but statistically significant increase in diagnosis of CRC at an early stage for patients who resided in expansion states. This trend is consistent with our previous analysis of our own cancer registry data in which we were able to show a highly significant shift in the diagnosis of CRC at an earlier stage with aggressive NY State Medicaid expansion from 2000 to 2012. The change in percentage of uninsured was much larger, 50%, and the comparison was over two decades[16]. It is likely that the Han analysis was too short a time period to confirm a difference.

Zerhouni et al[14], chose to parse the BRFSS database into 3 groups: Early expansion (2012), Expansion (2014 and 2016), and non-expansion states. Data from 2013 and 2015 were excluded. Their analysis concentrated on the differences in uptake over time. They also noted that each time period included different states that likely implemented the expansion in different ways. We chose to dichotomize the data and avoid any bias that may have been inadvertently created by the exclusion of specific years. These differences in design may explain why our results and conclusions diverge from Zerhouni. We found that Whites and Hispanics had greater uptake of CRC screening than Blacks. They concluded that Non-Hispanic Whites and Blacks benefited but that Hispanics did not. We certainly agree that the overall screening rate for Hispanics still lags Non-Hispanic Blacks and Whites. It is possible that other factors were needed to improve uptake of screening. Both studies evaluated the effect of income. Significant differences between expansion and non-expansion states occurred in each income group. Education level did reveal a difference, with subjects having graduated high school or more, showing more uptake of screening modalities.

It has been shown that low-income adults in Medicaid non expansion states are disproportionately Black and rural. This group is less likely to have a primary care provider or utilize preventive services. They are more likely to have out of pocket medical expenses and fill fewer prescriptions. These racial and geographic disparities strongly impact access to screening and cancer related outcomes. CRC screening specifically has been shown to be affected by the affordability of health insurance, associated cost-sharing by beneficiaries as well a lack of a recommendation for screening by a primary care provider[5-7]. With the passage of the ACA, there has been an increase in the number of individuals with a primary care provider and a decrease in the number of individuals who defer care due to cost[5]. Primary care providers are therefore able to have established relationships with their patients and refer them for preventive healthcare screenings including colonoscopies. It was thus surprising to note that this did not translate into an increase in utilization of screening services consistently across all socio-demographic groups including race/ethnicity, education status and income.

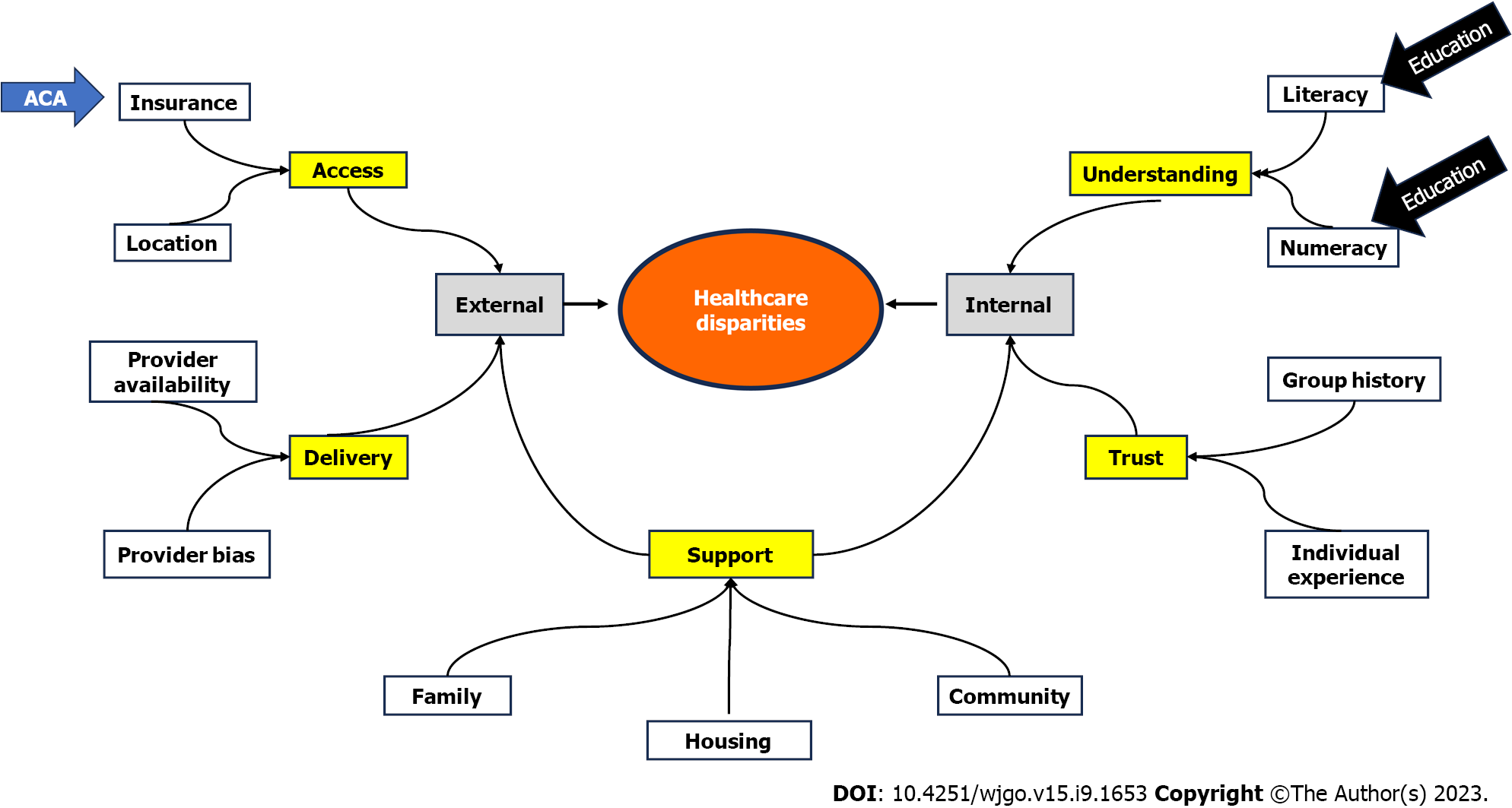

In our analysis, although Medicaid expansion had positively impacted Non-Hispanic Whites and Hispanics there was not enough evidence to conclude its effect on Non-Hispanic Blacks and other races. Even though our analysis covered most of the roll out of the ACA, this difference may be partly due to the limited period of analysis and perhaps there may be some delayed effect on Blacks and other races. However, the psychosocial determinants of healthcare represent a complex interplay of issues. Figure 1 summarizes factors we suggest may promote or inhibit healthcare disparities. Insurance coverage is the major external barrier to healthcare access. The ACA Medicaid expansion clearly addresses the issue of insurance coverage. However, there are internal patient factors including health care literacy, for which education level may be a surrogate indicator that can result in patients not taking advantage of increased access to care. It is also important to note that the impact of education on uptake of CRC screening was only significant in the low-income subgroup.

Our study has several strengths. Firstly, being an analytic study with a quasi-experimental design, we were able to provide moderately compelling evidence to establish cause and effect. This differentiates our study from others. The lack of randomization, however, prevents the establishment of causality. We limited the potential for confounders (including variations due to trends and controlling for exposure) by our use of the differences-in-differences statistical technique. In addition, this study design is particularly suitable for assessing the early effects of a policy change and not later effects as it is exposed to selection-maturation interaction which poses a threat to its internal validity. Our study utilized data from all states in the United States from randomly selected participants and this makes this generalizable to the US population. Other limitations of the study include the fact that the data had already been collected and thus restrictive on the inferences and assessments that can be made as the variables were already pre-determined. In addition to this, recall bias may be a concern as responses were dependent on subjects being able to recall details from the past year. Also, selection bias is possible as people who respond to surveys may be different from those people who chose to ignore the survey. Both of which may lead to a loss of internal validity.

In conclusion, Medicaid expansion under the ACA has led to an overall increase in self-reported use of CRC screening tests by adults aged 50-64 years in the United States. This finding was consistent across low-income populations, but not across all races or levels of education. Further analysis is needed to investigate other barriers to CRC screening that exist in Black and other Non-Hispanic multiracial groups including psychosocial and economic determinants of CRC screening choices.

Wide disparities exist in access to screening, management, treatment and outcomes of colorectal cancer (CRC) in the United States. With many barriers previously described, various health policies and interventions have been designed to address these disparities. With the passage of the Affordable Care Act about a decade ago, many researchers have shown that Medicaid expansion has led to an increase in insurance coverage but the actual utlization of this newly gained access especially by low-income populations and minority groups remain poorly described in the era of Medicaid expansion.

There are many factors at play in understanding healthcare disparities and outcomes including the interplay between individual and societal factors.

To investigate the effect of Medicaid expansion on low-income populations and minorities on utilization of access to various colon cancer screening modalities. Understanding utilization after Medicaid expansion is key in further decreasing gaps and barriers in CRC screening in the United States.

Our study used a quasi-experimental design (a “natural” experiment) given that only some states expanded Medicaid while others did not. Data was from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System for the period 2011 to 2016. The treatment variable for this study was Medicaid expansion status. A difference-in-differences technique was used to analyze the effect of Medicaid expansion status on the utilization of access to colorectal screening. Other secondary analysis included stratification of the access by ethnicity/race, income, and education status.

States that expanded Medicaid showed a greater increase in utilization of access to CRC screening. Among minority populations, our analysis revealed that Hispanics showed a greater statistically significant increase in utilization of access but not Non-Hispanic Blacks, or Multiracial. Low-income participants showed a higher change in access and utilization between the expansion periods compared with higher income groups. There was an increase in utilization across all educational levels particularly among those who reported having a high school graduate degree or more.

We conclude that Medicaid expansion under the ACA was associated with an overall increase in self-reported use of CRC screening tests by adults aged 50-64 years in the United States. This finding was consistent across low-income populations, but not across all races or levels of education. We suggest that despite equally gained access by low-income populations in expansion states, there may be other barriers to CRC screening that exist in Black and other Non-Hispanic multiracial groups including psychosocial and economic determinants of CRC screening choices.

Future studies should consider investigating economic determinants of CRC screening choices in minority populations.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author’s Membership in Professional Societies: American Gastroenterological Association; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; American College of Gastroenterology.

Specialty type: Health care sciences and services

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Bustamante-Lopez LA, Brazil; Sano W, Japan S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YL

| 1. | US Preventive Services Task Force, Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, Cabana M, Caughey AB, Davis EM, Donahue KE, Doubeni CA, Krist AH, Kubik M, Li L, Ogedegbe G, Owens DK, Pbert L, Silverstein M, Stevermer J, Tseng CW, Wong JB. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2021;325:1965-1977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 402] [Cited by in RCA: 1134] [Article Influence: 283.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jones RM, Devers KJ, Kuzel AJ, Woolf SH. Patient-reported barriers to colorectal cancer screening: a mixed-methods analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:508-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wilkins T, Gillies RA, Harbuck S, Garren J, Looney SW, Schade RR. Racial disparities and barriers to colorectal cancer screening in rural areas. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25:308-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Forum on Medical and Public Health Preparedness for Catastrophic Events; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Board on Health Care Services; Institute of Medicine. The Impacts of the Affordable Care Act on Preparedness Resources and Programs: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press, 2014. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK241401/. |

| 5. | Manchikanti L, Hirsch JA. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010: a primer for neurointerventionalists. J Neurointerv Surg. 2012;4:141-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rosenbaum S, Westmoreland TM. The Supreme Court's surprising decision on the Medicaid expansion: how will the federal government and states proceed? Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:1663-1672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Current Status of State Medicaid Expansion Decisions. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. [cited 20 July 2019]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/health-reform/slide/current-status-of-the-medicaid-expansion-decision/. |

| 8. | Elwood TW. Aftermath of the Supreme Court ruling on health reform. Int Q Community Health Educ. 32:267-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zerhouni YA, Scott JW, Ta C, Hsu PC, Crandall M, Gale SC, Schoenfeld AJ, Bottiggi AJ, Cornwell EE 3rd, Eastman A, Davis JK, Joseph B, Robinson BRH, Shafi S, White CQ, Williams BH, Haut ER, Haider AH. Impact of the Affordable Care Act on trauma and emergency general surgery: An Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma systematic review and meta-analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;87:491-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kamermayer AK, Leasure AR, Anderson L. The Effectiveness of Transitions-of-Care Interventions in Reducing Hospital Readmissions and Mortality: A Systematic Review. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2017;36:311-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sterbenz JM, Chung KC. The Affordable Care Act and Its Effects on Physician Leadership: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Qual Manag Health Care. 2017;26:177-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hendryx M, Luo J. Increased Cancer Screening for Low-income Adults Under the Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansion. Med Care. 2018;56:944-949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Han X, Yabroff KR, Ward E, Brawley OW, Jemal A. Comparison of Insurance Status and Diagnosis Stage Among Patients With Newly Diagnosed Cancer Before vs After Implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:1713-1720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zerhouni YA, Trinh QD, Lipsitz S, Goldberg J, Irani J, Bleday R, Haider AH, Melnitchouk N. Effect of Medicaid Expansion on Colorectal Cancer Screening Rates. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62:97-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Questionnaire Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System 2012 Questionnaire Table of Contents. 2012. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/index.html. |

| 16. | Siba Y, Culpepper-Morgan J, Schechter M, Alatevi E, Jallow S, Onaghise J, Sey A, Ozick L, Sabbagh R. A decade of improved access to screening is associated with fewer colorectal cancer deaths in African Americans: a single-center retrospective study. Ann Gastroenterol. 2017;30:518-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Han X, Nguyen BT, Drope J, Jemal A. Health-Related Outcomes among the Poor: Medicaid Expansion vs. Non-Expansion States. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0144429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fletcher G, Culpepper-Morgan J, Genao A, Alatevi E. Disparities in colorectal cancer screening: the effect of Affordable Care Act’s (ACA’s) Medicaid expansion on Minorities and Low-income populations. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:S-183. [DOI] [Full Text] |