Published online Mar 15, 2019. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v11.i3.238

Peer-review started: October 25, 2018

First decision: December 10, 2018

Revised: January 16, 2019

Accepted: January 29, 2019

Article in press: January 30, 2019

Published online: March 15, 2019

Processing time: 141 Days and 3.6 Hours

Cholangiocarcinoma is a highly lethal disease that had been underestimated in the past two decades. Many risk factors are well documented for in cholangiocarcinoma, but the impacts of advanced biliary interventions, like endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES), endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation (EPBD), and cholecystectomy, are inconsistent in the previous literature.

To clarify the risks of cholangiocarcinoma after ES/EPBD, cholecystectomy or no intervention for cholelithiasis using the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD).

From data of NHIRD 2004-2011 in Taiwan, we selected 7938 cholelithiasis cases as well as 23814 control group cases (matched by sex and age in a 1:3 ratio). We compared the previous risk factors of cholangiocarcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma rate in the cholelithiasis and control groups. The incidences of total and subsequent cholangiocarcinoma were calculated in ES/EPBD patients, cholecystectomy patients, cholelithiasis patients without intervention, and groups from the normal population.

In total, 537 cases underwent ES/EPBD, 1743 cases underwent cholecystectomy, and 5658 cholelithiasis cases had no intervention. Eleven (2.05%), 37 (0.65%), and 7 (0.40%) subsequent cholangiocarcinoma cases were diagnosed in the ES/EPBD, no intervention, and cholecystectomy groups, respectively, and the odds ratio for subsequent cholangiocarcinoma was 3.13 in the ES/EPBD group and 0.61 in the cholecystectomy group when compared with the no intervention group.

In conclusion, symptomatic cholelithiasis patients who undergo cholecystectomy can reduce the incidence of subsequent cholangiocarcinoma, while cholelithiasis patients who undergo ES/EPBD are at a great risk of subsequent cholangiocarcinoma according to our findings.

Core tip: There are many risk factors well demonstrated in cholangiocarcinoma, but the impacts of advanced biliary interventions, like endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES), endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation (EPBD) and cholecystectomy, are inconsistence in previous literature. We tried to evaluate the subsequent cholangiocarcinoma risk in cholelithiasis patients who underwent ES, EPBD and cholecystectomy. Cholecystectomy can reduce the incidence of subsequent cholangiocarcinoma, while cholelithiasis patients underwent ES/EPBD are in a huge risk of subsequent cholangiocarcinoma in our database study.

- Citation: Wang CC, Tsai MC, Sung WW, Yang TW, Chen HY, Wang YT, Su CC, Tseng MH, Lin CC. Risk of cholangiocarcinoma in patients undergoing therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography or cholecystectomy: A population based study. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2019; 11(3): 238-249

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v11/i3/238.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v11.i3.238

Cholangiocarcinoma, which arises from the epithelial cells of the intrahepatic or extrahepatic bile ducts, is a highly lethal disease that has been underestimated in the past two decades. Unlike the decline in mortality due to primary liver cancer, the mortality of intra-hepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) has increased in both sexes in Europe[1]. At the same time, previous studies have shown that the incidence of ICC has been rising, while the incidence of extra-hepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ECC) has declined internationally[2-5] in the past thirty years, except in Denmark[6]. Unfortunately, the global incidence data may be inaccurate because of ICC registered as part of primary liver cancer and ECC mixed with gallbladder cancers in the databases of many countries.

The previous literature has listed many well known risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma, such as primary sclerosing cholangitis[7-9], choledochal cyst disease[10,11], specific parasite infection[12], cholelithiasis[13,14], chronic hepatitis B and C (CHB and CHC) infection[15,16], diabetes mellitus (DM)[17,18] and Helicobacter infection (HP)[19,20]. However, the true etiology of cholangiocarcinoma is still a mystery, although several hypotheses have been proposed, including destruction of the integrity of the bile duct through procedures like therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or cholecystectomy. The major indications for ERCP are choledocholithiasis, rather than biliary or pancreatic neoplasms, or the need to manage postoperative biliary complications[21-23]. Therapeutic ERCP, including endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) and endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation (EPBD), has been considered to have increased future cholangiocarcinoma incidence for over a decade[24-26]. Because cholelithiasis itself is one of the risk factors of cholangiocarcinoma, the impact of the incidence of a subsequent cholangiocarcinoma for advanced bile duct management is hard to evaluate.

ES had been shown to increase biliary epithelial atypia[27], and previous data have indicated that therapeutic ERCP can increase the subsequent cholangiocarcinoma rate[28]. At the same time, many recent larger population-based studies have demonstrated that ES does not increase the incidence of cholangiocarcinoma[29-31]. Even some evidence has suggested that ES does not increase the subsequent cholangiocarcinoma rate over that seen with EPBD[29]. At the same time, cholelithiasis and cholecystectomy had been of concern due to the increase in ICC[32] and ECC[33], but some studies have shown that cholecystectomy decreases the subsequent cholangiocarcinoma rate in cholelithiasis patients[34].

The inconsistency of the previous evidence led us to conduct this study using the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) 2004-2011 in Taiwan. Our goal was to re-confirm the old risk factors in modern society and to clarify the risk of cholangiocarcinoma in the medium time period following therapeutic ERCP or cholecystectomy in cholelithiasis patients.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taiwan. The IRB waved the need for informed consent in this study as it is a retrospective study based on the NHIRD. All authors declare no any conflicts of interest.

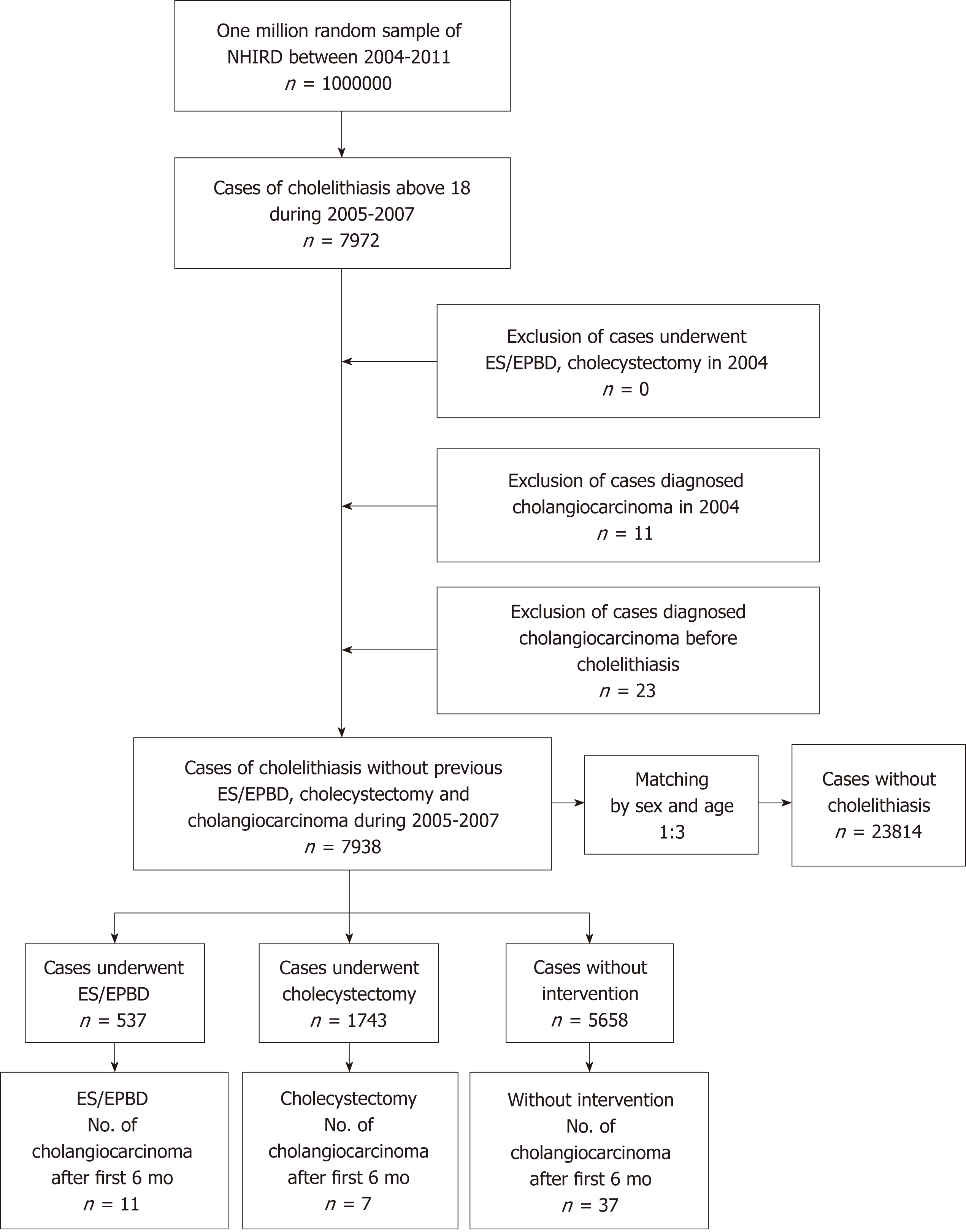

This study is a population-based retrospective cohort study based on Taiwan’s NHIRD, which covers more than 99% of the Taiwanese population[35]. The study methods of NHIRD have been described in detail in previous studies[36,37]. Symptomatic cholelithiasis cases with above 18 years of age were included from one million random samples of NHIRD data obtained between January 2005 and December 2007 using Codes of International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems-9th Edition (ICD-9), which were registered once in admission or three times in outpatient clinics to avoid bias from possible classification errors. After study group selection, we built the control group with propensity score matching by sex and age in a 1:3 ratio. The control group cases were defined as individuals who had neither been diagnosed with cholelithiasis nor undergone a related medical procedure, such as cholecystectomy or ERCP, in the previous year. Cholelithiasis patients who had undergone ES, EPBD, or cholecystectomy in the previous year or who were diagnosed after cholangiocarcinoma were excluded from further analysis. We then excluded patients, who diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma from January to December 2004 in both the control and study groups. The cholangiocarcinoma patients in Taiwan have catastrophic illness cards that waive their medical expenses by ICD-9 registration; therefore, we considered that a one year time period for exclusion was adequate. The variables such as economic status, place of residence, follow-up time, and cholangiocarcinoma rate, as well as the historical common risk factors, such as CHB, CHC, HP, DM, end-stage renal disease (ESRD) on dialysis, congenital cystic disease of liver (CCDL), Clonorchis Opisthorchis (CO), and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), were compared in cholelithiasis and control group.

The cases of cholelithiasis were divided into three groups of patients who underwent ES or EPBD, patients who underwent cholecystectomy, and patients without any therapeutic intervention between January 2005 to December 2011. The patients who underwent both ES/EPBD and cholecystectomy were registered in the ES/EPBD group in our settings. The details of study design are shown in Figure 1. The ICD-9 codes for the listed diseases and procedure codes are listed in Supplementary Table 1. The stratification of age, gender, economic status, place of residence, follow-up time, cholangiocarcinoma rate, and historical common risk factors were compared in each group. Patients who experienced cholangiocarcinoma in the first 6 mo after ES, EPBD, or cholecystectomy were excluded from further analysis, because these cases should be considered as misdiagnoses or concurrent malignancies rather than subsequent cholangiocarcinoma. The time cumulative risk of cholangiocarcinoma in the different groups was calculated.

| Cholelithiasis group n = 7938 | Control group n = 23814 | P value | |||

| N | SD, % | N | SD, % | ||

| Age, mean (SD) | 59.15 | 16.53 | 59.15 | 16.53 | 1 |

| Age, yr | |||||

| 18-49 | 38.89 | 7.38 | 38.94 | 7.38 | |

| 50-69 | 59.13 | 5.52 | 59.13 | 5.52 | |

| > 70 | 78.67 | 5.95 | 78.67 | 5.95 | |

| Gender | 1 | ||||

| Male | 3798 | 47.85 | 11394 | 47.85 | |

| Female | 4140 | 52.15 | 12420 | 52.15 | |

| Follow up time (mo), mean (SD) | 57.96 | 21.48 | 63.12 | 15.6 | < 0.001 |

| Economic status | < 0.001 | ||||

| MBS | 3963 | 49.92 | 11216 | 47.1 | |

| 1-3 times MBS | 3136 | 39.51 | 10217 | 42.9 | |

| Above 3 times MBS | 825 | 10.39 | 2336 | 9.81 | |

| Place of residence | 0.007 | ||||

| City | 5046 | 63.57 | 15078 | 63.32 | |

| Countryside | 2747 | 34.61 | 8403 | 35.29 | |

| Remote village | 131 | 1.65 | 287 | 1.21 | |

| Comorbidity | |||||

| CHB | 754 | 9.5 | 667 | 2.8 | < 0.001 |

| CHC | 542 | 6.83 | 474 | 1.99 | < 0.001 |

| HP | 128 | 1.61 | 131 | 0.55 | < 0.001 |

| DM | 2319 | 29.21 | 4327 | 18.17 | < 0.001 |

| ESRD | 186 | 2.34 | 357 | 1.5 | < 0.001 |

| CCDL | 51 | 0.64 | 7 | 0.03 | < 0.001 |

| CO | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| IBD | 119 | 1.5 | 184 | 0.77 | < 0.001 |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | |||||

| Number (rate) | 147 | 1.85 | 39 | 0.16 | < 0.001 |

| Follow up time (mo), mean (SD) | 13.92 | 21.96 | 31.8 | 21.48 | < 0.001 |

| Cholangiocarcinoma after first 6 mo | |||||

| Number (rate) | 55 | 0.69 | 35 | 0.15 | < 0.001 |

| Follow up time (mo), mean (SD) | 36.73 | 20.57 | 35.27 | 19.94 | 0.86 |

The NHIRD, which includes one a representative population of one million persons residing in Taiwan between 2004 and 2011 was managed using Microsoft SQL Server 2008 R2 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, United States) and the SQL programming language for the data query and data processing jobs. Statistical analysis was done using OpenEpi: Open source epidemiologic statistics for public health, version 3.01[38]. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were conducted using SPSS version 19. Person time analyses were done using OpenEpi version 3.01.

Data obtained from the study were compared with the use of the χ2 test for categorical variables, the t-test, or one-way ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) for continuous variables, and the Log Rank (Mantel-Cox) test for survival curves. A two-tailed P-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant in this study.

Because we used age and sex to find three times as many normal population subjects without cholelithiasis to be our control group, we could not evaluate age and sex as risk stratification in our comparisons of the cholelithiasis and control groups.

In total, 7938 adult cholelithiasis cases were selected from one million random samples of NHIRD data obtained between January 2005 and December 2007. The control group consisted of 23814 cases without cholelithiasis and matched by age and sex. The mean age of both groups was 59.15 ± 16.53 and the proportion of female patients was 52.15% in both groups. The mean follow up time was 57.96 ± 21.48 mo in cholelithiasis group and 63.12 ± 15.6 mo in the normal population in our analysis. Demographic data revealed that the cholelithiasis patients had a minimum basic salary (49.92%) and residence in a lived in remote villages (1.65%) and the differences were statistically significant when compared to the control group. The proportion of historical risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma, like CHB, CHC, HP, DM, ESRD, CCDL, and IBD, were 9.50% vs 2.80%, 6.83% vs 1.99%, 1.61% vs 0.55%, 29.21% vs 18.17%, 2.34% vs 1.50%, 0.64% vs 0.03% and 1.5% vs 0.77% in the cholelithiasis group versus the normal population, respectively. All the proportions of comorbidity were significantly high (P < 0.001) in the cholelithiasis group, except for CO infection because neither group showed CO infection. In total,147 cholelithiasis cases and 39 normal population cases experienced cholangiocarcinoma during the follow-up period. After exclusion of cases with cholangiocarcinoma in the initial 6 mo in both groups, 55 cholelithiasis cases and 35 normal population cases developed cholangiocarcinoma, with a mean follow up of 36.73 ± 20.57 mo and 35.27 ± 19.94 mo, respectively. The subsequent cholangiocarcinoma rate was higher in the cholelithiasis group than in the control group (0.69% vs 0.15%, P < 0.001). The detailed information is shown in Table 1.

There were 537 cases that underwent ES/EPBD, 1743 cases that underwent cholecystectomy, and 5658 cases that received no intervention, and we observed no significant difference in the mean age. However, the mean age after age stratification of patients above 70 years old was higher in the ES/EPBD group (79.11 ± 5.13), followed by the no intervention group (78.78 ± 6.08) and the cholecystectomy group (78.01 ± 5.54). Other demographic data in our analysis showed some differences: Follow-up time, place of residence, proportion of CHB, proportion of CHC, and proportion of CCDL. The details are shown in Table 2.

| ES/EPBD n = 537 | Cholecystectomy n = 1743 | Without intervention n = 5658 | P value | ||||

| N | SD, % | N | SD, % | N | SD, % | ||

| Age, mean (SD) | 64.33 | 16.33 | 56.95 | 16.53 | 59.34 | 16.43 | 0.941 |

| Age, yr | |||||||

| 18-49 | 39.29 | 7.59 | 38.26 | 7.6 | 39.09 | 7.27 | 0.391 |

| 50-69 | 60 | 5.2 | 59.3 | 5.56 | 58.99 | 5.53 | 0.559 |

| > 70 | 79.11 | 5.73 | 78.01 | 5.54 | 78.78 | 6.08 | 0.002 |

| Gender | 0.692 | ||||||

| Male | 264 | 49.16 | 843 | 48.36 | 2691 | 47.56 | |

| Female | 273 | 50.84 | 900 | 51.64 | 2967 | 52.44 | |

| Follow up time (mo), mean (SD) | 56.3 | 22.24 | 61.38 | 18.4 | 56.88 | 22.27 | < 0.001 |

| Economic status | 0.16 | ||||||

| MBS | 319 | 59.4 | 1137 | 65.23 | 3590 | 63.45 | |

| 1-3 times MBS | 209 | 38.92 | 574 | 32.93 | 1964 | 34.71 | |

| Above 3 times MBS | 9 | 1.68 | 28 | 1.61 | 94 | 1.66 | |

| Place of residence | 0.009 | ||||||

| City | 296 | 55.12 | 854 | 49 | 2813 | 49.72 | |

| Countryside | 205 | 38.18 | 681 | 39.07 | 2250 | 39.77 | |

| Remote village | 36 | 6.7 | 204 | 11.7 | 585 | 10.34 | |

| Comorbidity | |||||||

| CHB | 50 | 9.31 | 137 | 7.86 | 567 | 10.02 | 0.026 |

| CHC | 22 | 4.1 | 73 | 4.19 | 447 | 7.9 | < 0.001 |

| HP | 11 | 2.05 | 23 | 1.32 | 94 | 1.66 | 0.433 |

| DM | 167 | 31.1 | 478 | 27.42 | 1674 | 29.59 | 0.135 |

| ESRD | 12 | 2.23 | 37 | 2.12 | 137 | 2.42 | 0.76 |

| CCDL | 13 | 2.42 | 12 | 0.69 | 26 | 0.46 | < 0.001 |

| CO | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| IBD | 6 | 1.12 | 23 | 1.32 | 90 | 1.59 | 0.54 |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | |||||||

| Number of cholangiocarcinoma | 27 | 5.03 | 15 | 0.86 | 105 | 1.86 | < 0.001 |

| Number of cholangiocarcinoma after first 6 mo | 11 | 2.05 | 7 | 0.4 | 37 | 0.65 | < 0.001 |

| Odds ratio | 3.13 | 0.61 | 1 | ||||

| Number of cholangiocarcinoma after first 12 mo | 10 | 1.86 | 6 | 0.34 | 35 | 0.62 | < 0.001 |

| Odds ratio | 3.01 | 0.56 | 1 | ||||

| Time to diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma (excluding case in initial 6 mo), month | 41.17 | 22.51 | 33.7 | 23.35 | 35.46 | 19.08 | 0.698 |

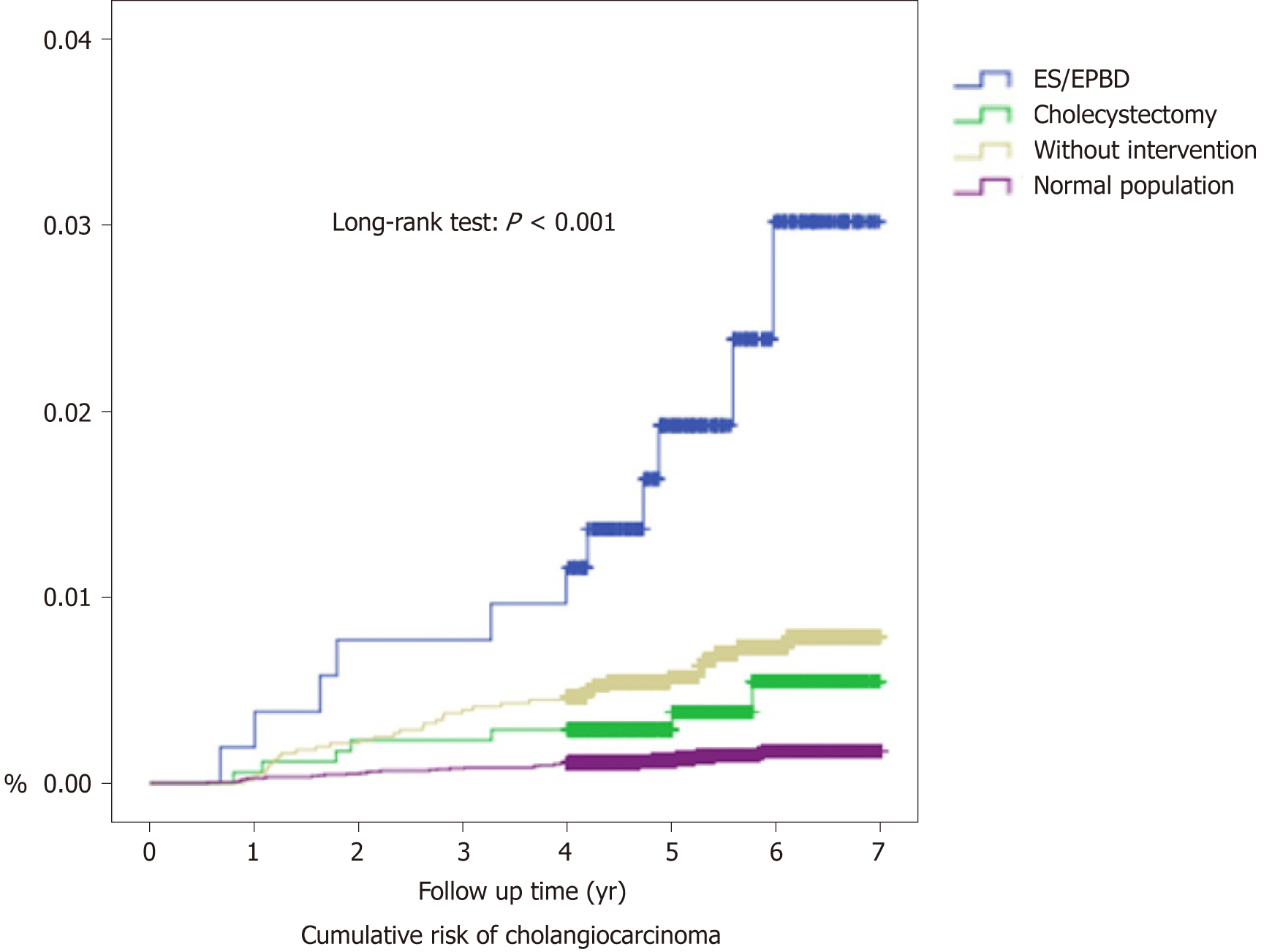

In total, 27 patients (5.03%) were diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma in the ES/EPBD group, while 105 (1.86%) were diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma in the no intervention group, and 15 (0.86%) were diagnosed in the cholecystectomy group during the follow-up period. After exclusion of possible misdiagnoses and concurrent cholangiocarcinoma, by excluding cholangiocarcinoma diagnosed within 6 mo after the procedure, 11 (2.05%), 37 (0.65%), and 7 (0.40%) cholangiocarcinoma cases were diagnosed in the ES/EPBD, no intervention, and cholecystectomy groups, respectively. The time to diagnosis for subsequent cholangiocarcinoma was 41.17 ± 22.51 mo in the ES/EPBD group, 35.46 ± 19.08 mo in the no intervention group, and 33.70 ± 23.35 mo in the cholecystectomy group. The odds ratio for subsequent cholangiocarcinoma was 3.13 in the ES/EPBD group and 0.61 in cholecystectomy group when compared with the no intervention group. The results were similar if we excluded the cholangiocarcinoma cases within one year after the procedure or the diagnosis of cholelithiasis. The cumulative cholangiocarcinoma rates in the three groups in the 7-year follow-up period are demonstrated in Figure 2.

The incidence of cholangiocarcinoma after the initial 6 mo was compared using incidence rate/1000 person-years. In the ES/EPBD group, the incidence of cholangiocarcinoma was 4.37 (2.30-7.59) per 1000 person-years, which is more than 15 times of the incidence of the normal population. The incidence of cholangiocarcinoma in ES/EPBD was especially high in females (6.31/1000 person-years) and patients older than 70 years (7.53/1000 person-years).

In the cholecystectomy group, the incidence of cholangiocarcinoma was 0.79 (0.34–1.55) per 1000 person-years, which is still higher than the cholangiocarcinoma incidence in the normal population. The highest incidence of cholangiocarcinoma was found in patients older than 70 years (2.15/1000 person-years).

The cholelithiasis patients without advanced intervention had an incidence of cholangiocarcinoma of 1.38 (0.99–1.88) per 1000 person-years. The highest incidence of cholangiocarcinoma in this subgroup was observed in men (1.72/1000 person-years) and in elderly patients (2.80/1000 person-years). The incidence comparisons are shown in Table 3. For the recurrent biliary events, the comparisons between cholangiocarcinoma patients and non-cholangiocarcinoma patients in ES/EPBD group were listed in the Supplementary Table 2.

| Variables | Person-years at risk in study cohort | Person-years at risk in control cohort | No. of observed cases of cholangiocarcinoma in study cohort | No. of observed cases of cholangiocarcinoma in control cohort | Incidence rate/1000 person-years (95%CI) in study cohort | Incidence rate/1000 person-years (95%CI) in control cohort |

| ES/EPBD | ||||||

| Total | 2519.33 | 125339.21 | 11 | 35 | 4.37 (2.30-7.59) | 0.28 (0.20-0.38) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 1252.12 | 59176.6 | 3 | 20 | 2.40 (0.61-6.52) | 0.34 (0.21-0.51) |

| Female | 1267.21 | 66162.61 | 8 | 15 | 6.31 (2.93-11.99) | 0.23 (0.13-0.37) |

| Age, yr | ||||||

| 18-49 | 561.74 | 37789.95 | 1 | 5 | 1.78 (0.09-8.78) | 0.13 (0.05-0.29) |

| 50-69 | 895.32 | 48272.57 | 2 | 14 | 2.23 (0.38-7.38) | 0.29 (0.17-0.48) |

| > 70 | 1062.27 | 39276.69 | 8 | 16 | 7.53 (3.50-14.30) | 0.41 (0.24-0.65) |

| Cholecystectomy | ||||||

| Total | 8911.32 | 125339.21 | 7 | 35 | 0.79 (0.34-1.55) | 0.28 (0.20-0.38) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 4187.56 | 59176.6 | 3 | 20 | 0.72 (0.18-1.95) | 0.34 (0.21-0.51) |

| Female | 4723.76 | 66162.61 | 4 | 15 | 0.85 (0.27-2.04) | 0.23 (0.13-0.37) |

| Age, yr | ||||||

| 18-49 | 3173.23 | 37789.95 | 1 | 5 | 0.32 (0.02-1.55) | 0.13 (0.05-0.29) |

| 50-69 | 3413.76 | 48272.57 | 1 | 14 | 0.29 (0.01-1.45) | 0.29 (0.17-0.48) |

| > 70 | 2324.33 | 39276.69 | 5 | 16 | 2.15 (0.79-4.77) | 0.41 (0.24-0.65) |

| Cholelithiasis without intervention | ||||||

| Total | 26820.41 | 125339.21 | 37 | 35 | 1.38 (0.99-1.88) | 0.28 (0.20-0.38) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 12201.3 | 59176.6 | 21 | 20 | 1.72 (1.09-2.59) | 0.34 (0.21-0.51) |

| Female | 14619.11 | 66162.61 | 16 | 15 | 1.09 (0.65-1.74) | 0.23 (0.13-0.37) |

| Age, yr | ||||||

| 18-49 | 8423.77 | 37789.95 | 4 | 5 | 0.48 (0.15-1.15) | 0.13 (0.05-0.29) |

| 50-69 | 10889.04 | 48272.57 | 12 | 14 | 1.10 (0.60-1.87) | 0.29 (0.17-0.48) |

| > 70 | 7507.6 | 39276.69 | 21 | 16 | 2.80 (1.78-4.20) | 0.41 (0.24-0.65) |

In our study, the intervention rate was higher than that reported previously[39], because this was a hospital-based cohort database, which meant that nearly all cholelithiasis cases were regarded as symptomatic patients. We found a higher incidence of cholelithiasis in people with a minimum basic salary and the highest economic status. The former seems connected with a poor health environment, as shown in previous literature[40], while the latter can be explained by diets high in cholesterol, saturated fat, and excess carbohydrates[41]. The same conditions explained the higher portion of cholelithiasis patients among residents of remote villages than in the normal population. Because primary sclerosing cholangitis[7-9], CCDL[10,11], CO[12], cholelithiasis[13,14], CHB and CHC[15,16], DM[17,18] and HP infection[19,20] are important risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma, we subjected these factors to further evaluation to compare cholelithiasis patients and a normal population. In our analysis, CHB, CHC, DM, HP infection, ESRD, CCDL, and IBD were more common in cholelithiasis patients and some of these factors logically increased the rate of cholangiocarcinoma by increasing the incidence of cholelithiasis[42]. Because CO infection is extremely rare in modern Taiwanese society, no CO-infected patient was found in our study in either group. The cholangiocarcinoma rate was higher in cholelithiasis patients than in the normal population (0.69% vs 0.15%), thereby confirming the previous concept of cholelithiasis as an important risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma.

The rate of total cholangiocarcinoma and subsequent cholangiocarcinoma (diagnosed 6 mo after procedure) are highest in ES/EPBD patients, followed by cholelithiasis patients without intervention, and the lowest cholangiocarcinoma rate was found in cholecystectomy patients. The odds ratio of ES/EPBD patients for cholangiocarcinoma was 3.13 when compared with no intervention, indicating that the subsequent cholangiocarcinoma rate was high after ES/EPBD in cholelithiasis patients. Cholecystectomy decreased the cholangiocarcinoma rate in cholelithiasis patients in our study and this effect was compatible with previous literature reports[34].

Another interesting finding of our study was the high incidence of cholangiocarcinoma in the medium time period for cholelithiasis patients who had undergone ES/EPBD, especially in women and in patients older than 70 years. However, current guidelines do not suggest close follow-up in these patients.

This study has two major limitations. First, this is a retrospective database cohort study that showed an increase in the further incidence of cholangiocarcinoma after EST/EPBD in cholelithiasis patients, but the true consequence of cholangiocarcinoma and ES/EPBD is unclear. Second, even though this is a one million representative database, the incidence of cholangiocarcinoma is so low that we only found 11 cases, 7 cases, and 37 cases in the ES/EPBD, cholecystectomy, and without intervention group, respectively, but the power of our results is still credible. We will try to initiate a prospective hospital-based cohort study in cholelithiasis patients, who underwent therapeutic intervention to clarify the consequence of cholangiocarcinoma in ES/EPBD and cholecystectomy patients.

In conclusion, symptomatic cholelithiasis did increase the cholangiocarcinoma rate in our analysis, and patients with cholelithiasis who underwent cholecystectomy could reduce the incidence of subsequent cholangiocarcinoma, but the incidence is still significantly higher than the incidence in the normal population. Meanwhile, the patients with cholelithiasis who undergo ES/EPBD are at high risk of subsequent cholangiocarcinoma.

Cholangiocarcinoma is a highly lethal disease. There are many well known risk factors of cholangiocarcinoma, most of them result from chronic biliary system inflammation, such as primary sclerosing cholangitis, choledochal cyst disease, specific parasite infection, cholelithiasis, chronic hepatitis B and C infection, diabetes mellitus and Helicobacter infection, but the impacts of advanced biliary interventions, like endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES), endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation (EPBD) and cholecystectomy, are inconsistence in previous literature. It is important to understand the major hypothesis result in cholangiocarcinoma.

We focused on the most common disease, cholelithiasis, which can result in cholangiocarcinoma. We conducted this study using the National Health Insurance Research Database to clarify the risks of cholangiocarcinoma after ES/EPBD, cholecystectomy or no intervention for cholelithiasis.

We try to evaluate hospital base cholelithiasis retrospective cohort and analyzed further cholangiocarcinoma risk in patients underwent ES/EPBD, cholecystectomy or no intervention for cholelithiasis. Further studies, to clarify whether the inflammation location or the different methods of therapeutic managements affect the incidence of cholangiocarcinoma, are needed in this field.

Because of cholangiocarcinoma is still a disease with very low incidence in normal population, we collect data of NHIRD 2004-2011 in Taiwan using one million random samples. We selected 7938 cholelithiasis cases as well as 23814 control group cases (matched by sex and age in 1:3 ratio). The incidences of total and subsequent cholangiocarcinoma were calculated in ES/EPBD patients, cholecystectomy patients, cholelithiasis patients without intervention and normal population. This topic is hard to be analyzed because subsequent cholangiocarcinoma incidence is low and both cholelithiasis and the managements for cholelithiasis maybe influence the cholangiocarcinoma rate.

There are 537 cases underwent ES/EPBD, 1743 cases underwent cholecystectomy and 5658 cases without intervention in our cholelithiasis cohort. Eleven (2.05%), 37 (0.65%) and 7 (0.40%) subsequent cholangiocarcinoma cases diagnosed in ES/EPBD, no intervention and cholecystectomy group respectively and the odds ratio for subsequent cholangiocarcinoma is 3.13 in ES/EPBD group and 0.61 in cholecystectomy group comparing with no intervention group.

Symptomatic cholelithiasis patients underwent cholecystectomy had the lowest incidence of subsequent cholangiocarcinoma, but the incidence is still higher than normal population. Patients underwent ES/EPBD are in a high risk of subsequent cholangiocarcinoma and a follow-up plane should be needed in these kinds of patients. The hypotheses of these results can be explained by both inflammation at bile ducts increases incidence of cholangiocarcinoma than inflammation at gallbladder, or cholecystectomy reduce recurrent biliary events in cholelithiasis patients and decrease future cholangiocarcinoma rates. We need a series studies to clarify this mystery we left today.

The future direction of research is to evaluate choledocholithiasis patients, who underwent therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with or without further cholecystectomy, and their subsequent cholangiocarcinoma incidence. Because we think the procedure related cholangiocarcinoma need longer time period to take place, the influences of subsequent cholangiocarcinoma between ES and EPBD may be clarified in whole population based cohort study.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Lan C S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Song H

| 1. | Bertuccio P, Bosetti C, Levi F, Decarli A, Negri E, La Vecchia C. A comparison of trends in mortality from primary liver cancer and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in Europe. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1667-1674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Welzel TM, McGlynn KA, Hsing AW, O'Brien TR, Pfeiffer RM. Impact of classification of hilar cholangiocarcinomas (Klatskin tumors) on the incidence of intra- and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:873-875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Patel T. Worldwide trends in mortality from biliary tract malignancies. BMC Cancer. 2002;2:10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 359] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | West J, Wood H, Logan RF, Quinn M, Aithal GP. Trends in the incidence of primary liver and biliary tract cancers in England and Wales 1971-2001. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1751-1758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Patel T. Increasing incidence and mortality of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. Hepatology. 2001;33:1353-1357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 773] [Cited by in RCA: 797] [Article Influence: 33.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jepsen P, Vilstrup H, Tarone RE, Friis S, Sørensen HT. Incidence rates of intra- and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas in Denmark from 1978 through 2002. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:895-897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bergquist A, Ekbom A, Olsson R, Kornfeldt D, Lööf L, Danielsson A, Hultcrantz R, Lindgren S, Prytz H, Sandberg-Gertzén H, Almer S, Granath F, Broomé U. Hepatic and extrahepatic malignancies in primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2002;36:321-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 531] [Cited by in RCA: 469] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Burak K, Angulo P, Pasha TM, Egan K, Petz J, Lindor KD. Incidence and risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:523-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 415] [Cited by in RCA: 366] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chapman MH, Webster GJ, Bannoo S, Johnson GJ, Wittmann J, Pereira SP. Cholangiocarcinoma and dominant strictures in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis: a 25-year single-centre experience. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:1051-1058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Scott J, Shousha S, Thomas HC, Sherlock S. Bile duct carcinoma: a late complication of congenital hepatic fibrosis. Case report and review of literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1980;73:113-119. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Lipsett PA, Pitt HA, Colombani PM, Boitnott JK, Cameron JL. Choledochal cyst disease. A changing pattern of presentation. Ann Surg. 1994;220:644-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Watanapa P, Watanapa WB. Liver fluke-associated cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2002;89:962-970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Welzel TM, Mellemkjaer L, Gloria G, Sakoda LC, Hsing AW, El Ghormli L, Olsen JH, McGlynn KA. Risk factors for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in a low-risk population: a nationwide case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:638-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hsing AW, Gao YT, Han TQ, Rashid A, Sakoda LC, Wang BS, Shen MC, Zhang BH, Niwa S, Chen J, Fraumeni JF. Gallstones and the risk of biliary tract cancer: a population-based study in China. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:1577-1582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shin HR, Lee CU, Park HJ, Seol SY, Chung JM, Choi HC, Ahn YO, Shigemastu T. Hepatitis B and C virus, Clonorchis sinensis for the risk of liver cancer: a case-control study in Pusan, Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:933-940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shaib YH, El-Serag HB, Davila JA, Morgan R, McGlynn KA. Risk factors of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a case-control study. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:620-626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 401] [Cited by in RCA: 385] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Jing W, Jin G, Zhou X, Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Shao C, Liu R, Hu X. Diabetes mellitus and increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2012;21:24-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Zhang LF, Zhao HX. Diabetes mellitus and increased risk of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a meta-analysis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60:684-687. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Chang JS, Tsai CR, Chen LT. Medical risk factors associated with cholangiocarcinoma in Taiwan: a population-based case-control study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Murphy G, Michel A, Taylor PR, Albanes D, Weinstein SJ, Virtamo J, Parisi D, Snyder K, Butt J, McGlynn KA, Koshiol J, Pawlita M, Lai GY, Abnet CC, Dawsey SM, Freedman ND. Association of seropositivity to Helicobacter species and biliary tract cancer in the ATBC study. Hepatology. 2014;60:1963-1971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Maple JT, Ben-Menachem T, Anderson MA, Appalaneni V, Banerjee S, Cash BD, Fisher L, Harrison ME, Fanelli RD, Fukami N, Ikenberry SO, Jain R, Khan K, Krinsky ML, Strohmeyer L, Dominitz JA. The role of endoscopy in the evaluation of suspected choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 380] [Cited by in RCA: 335] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 22. | Baron TH, Mallery JS, Hirota WK, Goldstein JL, Jacobson BC, Leighton JA, Waring JP, Faigel DO. The role of endoscopy in the evaluation and treatment of patients with pancreaticobiliary malignancy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:643-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Costamagna G, Shah SK, Tringali A. Current management of postoperative complications and benign biliary strictures. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2003;13:635-648, ix. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sheth SG, Howell DA. What are really the true late complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy? Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2699-2701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bergman JJ, van Berkel AM, Groen AK, Schoeman MN, Offerhaus J, Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. Biliary manometry, bacterial characteristics, bile composition, and histologic changes fifteen to seventeen years after endoscopic sphincterotomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:400-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kurumado K, Nagai T, Kondo Y, Abe H. Long-term observations on morphological changes of choledochal epithelium after choledochoenterostomy in rats. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:809-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kalaitzis J, Vezakis A, Fragulidis G, Anagnostopoulou I, Rizos S, Papalambros E, Polydorou A. Effects of endoscopic sphincterotomy on biliary epithelium: a case-control study. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:794-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Oliveira-Cunha M, Dennison AR, Garcea G. Late Complications After Endoscopic Sphincterotomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2016;26:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Peng YC, Lin CL, Hsu WY, Chow WK, Lee SW, Yeh HZ, Chang CS, Kao CH. Association of Endoscopic Sphincterotomy or Papillary Balloon Dilatation and Biliary Cancer: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Langerth A, Sandblom G, Karlson BM. Long-term risk for acute pancreatitis, cholangitis, and malignancy more than 15 years after endoscopic sphincterotomy: a population-based study. Endoscopy. 2015;47:1132-1136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Strömberg C, Böckelman C, Song H, Ye W, Pukkala E, Haglund C, Nilsson M. Endoscopic sphincterotomy and risk of cholangiocarcinoma: a population-based cohort study in Finland and Sweden. Endosc Int Open. 2016;4:E1096-E1100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Guo L, Mao J, Li Y, Jiao Z, Guo J, Zhang J, Zhao J. Cholelithiasis, cholecystectomy and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Ther. 2014;10:834-838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Tao LY, He XD, Qu Q, Cai L, Liu W, Zhou L, Zhang SM. Risk factors for intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a case-control study in China. Liver Int. 2010;30:215-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Nordenstedt H, Mattsson F, El-Serag H, Lagergren J. Gallstones and cholecystectomy in relation to risk of intra- and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1011-1015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Cheng TM. Taiwan's new national health insurance program: genesis and experience so far. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003;22:61-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 522] [Cited by in RCA: 522] [Article Influence: 23.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Wu CY, Kuo KN, Wu MS, Chen YJ, Wang CB, Lin JT. Early Helicobacter pylori eradication decreases risk of gastric cancer in patients with peptic ulcer disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1641-8.e1-2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Wu CY, Chan FK, Wu MS, Kuo KN, Wang CB, Tsao CR, Lin JT. Histamine2-receptor antagonists are an alternative to proton pump inhibitor in patients receiving clopidogrel. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1165-1171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Dean AG, Sullivan KM, Soe MM. OpenEpi: Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health, Version 3.01, updated Apr 6, 2013, accessed Jan 6, 2018. Available from: URL: http://www.openepi.com/Menu/OE_Menu.htm. |

| 39. | Lirussi F, Nassuato G, Passera D, Toso S, Zalunardo B, Monica F, Virgilio C, Frasson F, Okolicsanyi L. Gallstone disease in an elderly population: the Silea study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:485-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Naeem M, Rahimnajjad NA, Rahimnajjad MK, Khurshid M, Ahmed QJ, Shahid SM, Khawar F, Najjar MM. Assessment of characteristics of patients with cholelithiasis from economically deprived rural Karachi, Pakistan. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Gaby AR. Nutritional approaches to prevention and treatment of gallstones. Altern Med Rev. 2009;14:258-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Acalovschi M, Buzas C, Radu C, Grigorescu M. Hepatitis C virus infection is a risk factor for gallstone disease: a prospective hospital-based study of patients with chronic viral C hepatitis. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16:860-866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |