Published online Aug 16, 2017. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v9.i8.417

Peer-review started: December 1, 2016

First decision: February 20, 2017

Revised: March 13, 2017

Accepted: April 23, 2017

Article in press: April 24, 2017

Published online: August 16, 2017

Processing time: 254 Days and 14 Hours

Russell body gastritis (RBG) is an unusual type of chronic gastritis characterized by marked infiltration of Mott cells, which are plasma cells filled with spherical eosinophilic bodies referred to as Russell bodies. It was initially thought that Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection was a major cause of RBG and that the infiltrating Mott cells were polyphenotypic; however, a number of cases of RBG without H. pylori infection or with monoclonal Mott cells have been reported. Thus, diagnostic difficulty exists in distinguishing RBG with monoclonal Mott cells from malignant lymphoma. Here, we report an unusual case of an 86-year-old-Japanese man with H. pylori-positive RBG. During the examination of melena, endoscopic evaluation confirmed a 13-mm whitish, flat lesion in the gastric antrum. Magnification endoscopy with narrow-band imaging suggested that the lesion was most likely a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. Biopsy findings were consistent with chronic gastritis with many Mott cells with intranuclear inclusions referred to as Dutcher bodies. Endoscopic submucosal dissection confirmed the diagnosis of RBG with kappa-restricted monoclonal Mott cells. Malignant lymphoma was unlikely given the paucity of cytological atypia and Ki-67 immunoreactivity of monoclonal Mott cells. This is the first reported case of RBG with endoscopic diagnosis of malignant tumor and the presence of Dutcher bodies.

Core tip: We report Russell body gastritis (RBG) evaluated by magnification endoscopy with narrow band imaging and pathological evaluation by endoscopic submucosal dissection. The endoscopic features of RBG are exclusively inflammatory; however, our detailed endoscopic evaluation led to misdiagnosis of the lesion as poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. The histological features of RBG were also unique because the presence of Mott cells with light chain restriction and Dutcher bodies suggested malignant lymphoma. Pathologists should be aware of the existence of this pathological entity, and clinicians should consider RBG as a differential diagnosis in cases where detailed endoscopic examination reveals poorly differentiated early gastric cancer.

- Citation: Yorita K, Iwasaki T, Uchita K, Kuroda N, Kojima K, Iwamura S, Tsutsumi Y, Ohno A, Kataoka H. Russell body gastritis with Dutcher bodies evaluated using magnification endoscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 9(8): 417-424

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v9/i8/417.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v9.i8.417

Russell body gastritis (RBG) was first described by Tazawa et al[1] in 1998 and is considered as a unique form of chronic gastritis characterized by infiltration of plasma cells filled with spherical eosinophilic cytoplasmic globules, referred to as Russell bodies. The endoscopic features of RBG are most in keeping with an inflammatory condition, and biopsy is required to confirm the pathological diagnosis. RBG is considered a reactive condition; however, monoclonal Mott cells have been shown in a number of cases of RBG, and therefore whether or not RBG with monoclonal Mott cells is benign remains debatable. This uncertainty is due to the fact that monoclonal Mott cells can show regional lymph node metastasis[2] and have been identified in mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma with extreme plasmacytoid differentiation[3]. Here, we report a unique case of RBG with endoscopic features of a malignant tumor, which consisted of monoclonal Mott cells with Dutcher bodies identified histologically following endoscopic submucosal resection.

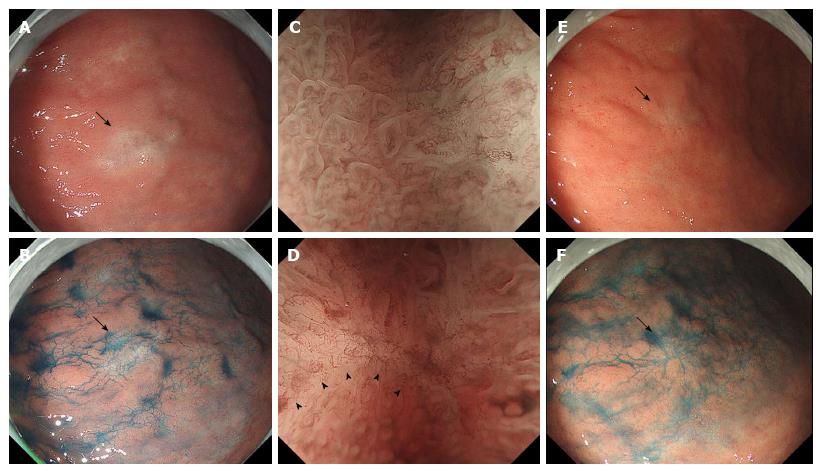

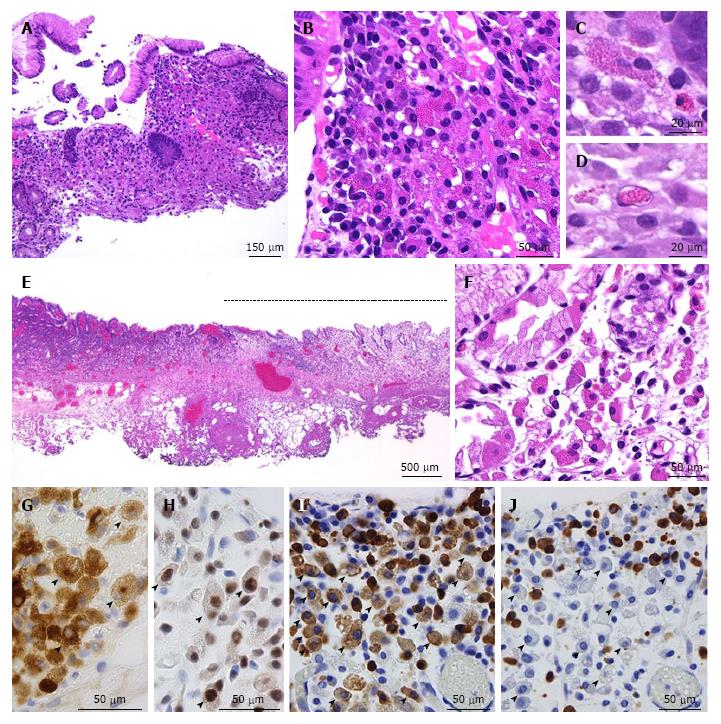

An 86-year-old Japanese man with a history of rheumatoid arthritis, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hypertension was referred to our medical center with melena. He took non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for arthralgia but did not take immunosuppressive drugs. Physiological examination was unremarkable. Laboratory findings revealed anemia (Hb 6.5 g/dL) and no other abnormal results. Endoscopic evaluation of the upper and lower digestive tracts did not reveal any active bleeding. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection was confirmed on a positive serum anti-H. pylori antibody test. The patient was initially diagnosed with atrophic and erosive gastritis secondary to H. pylori infection, and eradication therapy was initiated. The first esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed a 13-mm flat lesion (Figure 1A and B) of white and slightly brown discoloration in the lesser curvature of the antrum. A magnification endoscope (Gastrointestinal fiber-H260Z, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a narrow-band imaging (NBI) system (EVIS LUCERA SPECTRUM ELITE system, Olympus) was used, and magnification endoscopy with NBI (M-NBI) of the lesion showed loss or irregularity of microsurface pattern, irregular microvascular proliferation, and a demarcation line (Figure 1C and D). Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma was suspected, and a biopsy was performed. The duodenum appeared to be intact. The biopsy specimen (Figure 2A-D) showed chronic gastritis with infiltration of lymphocytes, plasma cells, eosinophils, and small- to large-sized granulated cells (Figure 2B-D). Spiral-shaped bacilli were focally located in the mucin on the foveolar epithelium, confirming the diagnosis of H. pylori. Substantial amounts of granulated cells with eosinophilic cytoplasmic granules and eccentric nuclei were seen (Figure 2B), which were of a similar size to the eosinophilic granules (Figure 2C). The small-sized granulated cells showed plasmacytoid morphology with eccentric and cartwheel-like nuclei, while ballooning large granulated cells showed histiocytoid morphology (Figure 2C). Intranuclear eosinophilic granules were also observed in some granulated cells (Figure 2D) but were not apparent in infiltrating plasma cells without cytoplasmic granules. Lymphoid follicles were not observed. Neither lymphoepithelial lesions nor monotonous proliferation of centrocyte-like cells or monocytoid-B cells were observed. The cytoplasmic granules were stained by phosphotungstic acid-hematoxylin (PTAH) and periodic acid Schiff with or without diastase treatment. Immunohistochemically, the granulated cells including histiocytoid cells were positive for CD79a (Clone HM57, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) and multiple myeloma oncogene 1 (Clone MUM1p, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) and negative for pancytokeratin (Clone CAM5.2, Becton Dickinson, CA), CD20 (Clone L26, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark), CD138 (Clone MI15, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark), CD68 (Clone KP-1, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark), CD163 (10D6, Thermo scientific), CD1a (Clone 10, DAKO, CA), S100 (polyclonal, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark), c-KIT (polyclonal, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark), mast cell tryptase (Clone AA1, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark), and Ki-67 (Clone MIB-1, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark). Thus, the granulated cells were considered to be plasma cells and identified as Mott cells with cytoplasmic eosinophilic globules (Russell bodies). Intranuclear eosinophilic granules in some Mott cells were considered to be Dutcher bodies. Immunohistochemically, the Mott cells appeared to be negative for light chains and immunoglobulin G (IgG, polyclonal, Novocastra Laboratories Ltd., Newcastle, United Kingdom), IgA (polyclonal, Novocastra Laboratories Ltd., Newcastle, United Kingdom), and IgM (polyclonal, Novocastra Laboratories Ltd., Newcastle, United Kingdom), while plasma cells without Russell bodies showed polytypic light chain staining pattern and were reactive for IgG, IgA, or IgM in varying proportions. Taken together, these findings were most in keeping with a diagnosis of RBG, but malignant lymphoma, particularly MALT lymphoma, was a differential diagnosis. However, chest-abdomen-pelvis computed tomography showed no abnormal mass, no swollen lymph nodes, and no lytic bone lesion. Two months after completion of eradication therapy, the patient consented to undergo endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), which was performed with the aim of histologically evaluating the entire lesion. After eradication therapy, the mucosal lesion decreased in size to 7 mm in diameter (Figure 1E-F) and loss or irregularity of the microsurface pattern, irregular microvascular proliferation, and a demarcation line with M-NBI were seen. ESD was successfully performed. The patient was discharged without any complications and there was no endoscopic evidence of recurrence 14 mo after the ESD treatment.

The endoscopically resected tissue was extended on a board with pins, fixed in 10% formalin for 24 h, cut into 2- to 3-mm thick sections, and embedded in paraffin. Four µm-thick sections were obtained from the paraffin blocks and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Pathology showed that the mucosal lesion had regional accumulation of substantial amounts of granulated cells associated with mild lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltration (Figure 2E and F). The immunohistochemical results of ESD were similar to those of the biopsy specimens (Figure 2G and H). In situ hybridization revealed that the Mott cells showed kappa light chain restriction (Figure 2I and J), whereas the plasma cells without Russell bodies were polyphenotypic. Cellular atypia and mitosis were not seen in the plasma cells or Mott cells, and less than 1% of the infiltrating cells were Ki67-positive, whereas no Mott cells were Ki67-positive. At the periphery of the lesion and in the background mucosa and submucosa, Mott cells and Dutcher bodies were absent. Lymphoid follicles were observed in the periphery of the lesion and the background mucosa, but not within the collection of Mott cells. There were no pathological features suggestive of carcinoma or MALT lymphoma. Amyloid deposition was unlikely because no amorphous materials were identified, and there was no characteristic apple green birefringence noted when the Congo Red stained section was viewed under polarized light. Thus, our final diagnosis was Russell body gastritis. However, the diagnostic assessment utilized had several limitations, as we did not assess for the presence of M protein in the serum, Bence-Jones protein in the urine, or genetic alterations in the immunoglobulin locus, and we did not perform cytopathological examination of the bone marrow.

We presented a unique case of RBG with H. pylori infection. Russell body gastritis is characterized by a dense accumulation of plasma cells with Russell bodies, referred to as Mott cells[1]. Russell bodies are eosinophilic spherical or globular cytoplasmic inclusions in plasma cells that were first described by Russell et al[4] in 1890. The globules differ from normal secretory granules in that they are larger and much more electron dense, and they lie in the distended cisternae of the rough endoplasmic reticulum[5]. These globules mainly consist of condensed immunoglobulin[6] and are related to abnormalities in the synthesis, trafficking, or excretion of immunoglobulin[7]. The Russell bodies seen in the present case were much smaller compared to those in previous reports; however, the granules were stained positive by periodic acid Schiff and PTAH, as described in previous case reports of RBG[8,9].

Table 1 summarizes the results of 31 previously published cases of RBG, including our own[1,8-25]. We excluded two cases reported as RBG[26] and Russell body carditis[27] because in these cases the inflammation site was at the esophagogastric junction. One case of RBG associated with advanced signet ring cell cancer[28] was also excluded because the authors did not describe whether or not RBG was present in the background gastric mucosa. The mean age of the patients described in previous case reports of RBG was 60 (range 24 to 86) years old, and our patient was the oldest. The male (n = 19) to female (n = 12) ratio was approximately 2:1. Twenty-one cases (68%) of RBG accompanied H. pylori infection, and the majority of patients in all cases presented with non-specific symptoms. The gastric antrum appears to be the predominant location for RBG, although there is one reported case of an immunocompromised patient with RBG associated with Russell body enterocolitis[25].

| Ref. | Age/sex | Endoscopic finding or diagnosis (size) | Site of mott cells | HP | Mott cells | ET and follow-up |

| Tazawa et al[1] (1998) | 53/M | Multiple ulcer scars with redness and swelling | Antrum | Yes | Poly | Follow-up biopsy after ET showed no RBG Follow-up period was not available |

| Erbersdobler et al[8] (2004) | 80/F | Circumscribed irregular swelling (30 mm) | Fundus | No | Poly | NA |

| Ensari et al[10] (2005) | 70/M | Pangastritis/flattened, edematous gastric folds | Body and antrum | Yes | Poly | ET was performed, but patient refused to be re-examined endoscopically |

| Drut et al[11] (2006) | 34/M | A raised, swollen area (20 mm) | Body | No | Poly | NA |

| Paik et al[12] (2006) | 47/F | Focal erythematous swelling | Antrum | Yes | Poly | ET was performed. Follow-up data: NA |

| 53/F | A geographical yellowish raised lesion (25 mm) | Body | Yes | Poly | ET was performed | |

| Follow-up data: NA | ||||||

| Wolkersdorfer et al[13] (2006) | 54/M | Mild erythema and small erosions with slight edema | Antrum | Yes | Mono (λ chain) | One year after ET, the lesion had not resolved macroscopically, but biopsy found resolution of Mott cells |

| Pizzolitto et al[14] (2007) | 60/F | Minute-raised granular areas | Antrum | Yes | Poly | ET was performed, and clinical follow-up was uneventful |

| Licci et al[15] (2008) | 59/M | Mild hyperemia | Antrum | Yes | Poly | Mott cells were absent in biopsy specimen taken 3 mo after ET |

| Tabata et al[16] (2010) | 72/M | Multiple ulcers | Body and antrum | Yes | Mono (κ chain, IgG) | Mott cells were absent in biopsy specimen taken 3 mo after ET |

| Habib et al[17] (2010) | 75/M | Noduar chronic active gastritis | Antrum | No | Poly | NA |

| Miura et al[18] (2012) | 63/F | Low elevated lesions in the antrum | Antrum | Yes | Mono (λ chain) | Mott cells were absent in biopsy specimen taken 4 mo after ET |

| Yoon et al[19] (2012) | 57/M | A slightly raised whitish lesion with a mild central depression (20 mm) | Body | Yes | Poly | The lesions were cleared 3 mo after ET. A follow-up biopsy was not performed |

| 43/M | A whitish oval shaped flat lesion with a slight central depression (20 mm) | Antrum | Yes | Poly | The lesions were cleared 2 mo after ET. A follow-up biopsy was not performed | |

| Choi et al[20] (2012) | 55/M | A mucosal elevation with a central depression (10 mm) | Antrum | Yes | Mono (λ chain) | NA |

| Karabagli et al[21] (2012) | 60/M | Erythema (body) and ulcer (incisura angularis) | Body and antrum | Yes | Poly | Three months and 6 mo after ET, Mott cells were decreased and absent in biopsy specimens, respectively |

| Coyne et al[22] (2012) | 49/M | Severe, raised, erosive gastritis | NA (Biopsy site; NA) | No | Mono (κ chain, IgM) | NA |

| Araki et al[9] (2013) | 74/F | Open ulcer | Gastric angle | Yes | Mono (κ chain, IgM) | NA |

| Zhang et al[23] (2014) | 78/F | Uneven mucosa | Body, incisura angularis, antrum | No | Mono (κ chain) | Clinical follow-up evaluations were uneventful |

| 77/F | Uneven mucosa | Incisura angularis | Yes | Mono (κ chain) | ||

| 77/F | punctiform erosion | Body | Yes | Mono (κ chain) | ||

| 56/M | Raised erosions | Antrum | Yes | Mono (κ chain) | ||

| 76/M | Erythema | Body | Yes | Mono (κ chain) | ||

| 50/M | Flat and raised erosions | Antrum | Yes | Mono (κ chain) | ||

| 28/M | Erythema | Antrum | No | Mono (κ chain) | ||

| 24/F | Erythema | Antrum | No | Mono (κ chain) | ||

| 66/M | Ulcer, stage A2 | Incisura angularis | No | NA | ||

| Klair et al[24] (2014) | 76/F | Cobblestoned, whitish, raised, and irregular mucosa | Fundus | No | Poly | NA |

| Muthukumarana et al[25] (2015) | 44/M | Diffuse mild erythematous gastric mucosa | Stomach, duodenum, terminal ileum, colon | No | Poly | NA |

| Nishimura et al[29] (2016) | 64/F | A white, granular lesion (2 cm) | Body | Yes | Poly | The lesion had grown larger 15 mo after the diagnosis, and the lesion had disappeared 15 mo after eradication |

| Present case | 86/M | A demarcated whitish flat lesion (13 mm) | Antrum | Yes | Mono (κ chain) | Two months after ET, the lesion decreased in size. There was no evidence of recurrence 14 mo after ESD |

The endoscopic features of RBG are non-specific, and in most cases, the inflammatory phenotype of the condition has been attributed largely to the presence of swollen, erythematous mucosa. The pathological features of RBG can mimic those of gastric xanthoma[19]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of RBG with a clinical diagnosis highly suggestive of a malignant tumor. In the present case, M-NBI confirmed a flat mucosal lesion in the antrum with a demarcated line, loss of microsurface pattern, and irregular microvascular proliferation. Nishimura et al[29] also reported that partial loss of microsurface structure and abnormal microvessels were observed in a case of RBG with M-NBI, but the demarcation line of RBG was not reported. Magnification endoscopy permits visualization of mucosal details that cannot be seen with standard endoscopy, and NBI is a novel endoscopic approach to visualize the microvasculature on the tissue surface. M-NBI has been proven to be highly sensitive, specific, and accurate at detecting early gastric neoplasms. Pathological evaluation revealed that the lesion was characterized by regional and intramucosal accumulation of Mott cells. The proliferation of Mott cells might induce expansion of the lamina propria, decrease the density of gastric glands and pits, and influence the microvasculature of the lesion. At present, RBG is considered a rare entity, but its incidence may increase in the future secondary to the increased use of M-NBI. It may be better that clinicians raise RBG as a differential diagnosis of poorly differentiated early gastric cancer upon examination by M-NBI.

Of pathological interest, Mott cells were monoclonal and had Dutcher bodies, which caused difficulty in making a histological diagnosis. Only two cases[8,12] of RBG and Dutcher bodies have been described in the literature to date, and both failed to identify a Dutcher body in the lesion. Considering the presence of monoclonal Mott cells and Dutcher bodies, the differential diagnoses that we considered were plasma cell neoplasm, MALT lymphoma, and lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma. In the present case, MALT lymphoma could not be diagnosed on account of the lack of histological features suggestive of MALT lymphoma, such as a lymphoepithelial lesion and proliferation of monocytoid B-cells or centrocyte-like cells. Moreover, Mott cells showed neither cellular atypia nor mitotic activity. Plasma cell neoplasm was excluded due to hypoproteinemia, lack of osteolysis in computed tomography images, and lack of nuclear atypia or mitotic activity of monoclonal Mott cells, although paraproteinemia was not evaluated via serum protein electrophoresis. Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma was ruled out because of an absence of splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance[13], which can be associated with H. pylori-positive RBG, could not be evaluated in this case.

The pathogenesis of RBG remains unknown. Tazawa et al[1] firstly postulated that RBG might be induced by H. pylori infection, and this is in keeping with previously published literature, in which two thirds of RBG cases were H. pylori-positive (Table 1). A recent study[30] showed that H. pylori with vacA m1 genotype produces more prominent Russell bodies in the antrum but not in the body. Indeed, the literature review revealed that the incidence of antral RBG was higher in H. pylori-positive cases (70%) than in H. pylori-negative cases (40%). On the other hand, our case showed endoscopic regression of the lesion from 13 mm to 7 mm at 2 mo after eradication of H. pylori, and similar findings were observed in previous studies[16,18,19,21]. These observations suggest that the successful eradication of H. pylori may eliminate the proliferative stimulation of Mott cells. However, case reports of RBG without H. pylori infection have also been described, although those cases were complicated by HIV infection[11], post-transplant status[25], or monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance[13]. Therefore, it is likely that H. pylori-unrelated pathogenesis of RBG is present, and an immunocompromised status may be partly related to the occurrence of RBG. In our case, the patient was elderly and had a history of rheumatoid arthritis; therefore, it is possible that the occurrence of RBG in this patient may have been due, in part, to his immunocompromised status.

RBG is considered to be a benign condition, and clinical follow-up data of 19 cases of RBG to date has failed to reveal any malignant change (Table 1). Among the 19 cases described in the literature, ten cases received H. pylori eradication therapy after diagnosis of RBG, and most of these showed endoscopic or histological resolution at three months, whether or not monoclonal Mott cells were present. Thus, follow-up might be a better approach for the present case. However, whether or not RBG with monoclonal Mott cells is a reactive or neoplastic phenomenon remains debatable. To date, a total of 15 cases (50%, 15/30) of RBG with monoclonal Mott cells, including our case, have been described, and all of these RBG cases had uneventful clinical follow-up. Brink et al[31] reported a case with a rectal tubulovillous adenoma accompanied by a proliferation of monoclonal Mott cells and concluded that the phenomenon indicated an inflammatory response. As Araki et al[9] discussed, monoclonal B cell proliferation can be seen in cases of chronic inflammation such as lymphoid follicle-forming gastritis[32], Sjögren’s syndrome[33], Hashimoto’s thyroiditis[34], and chronic liver disease secondary to hepatitis C virus[35]. Thus, the above data support the theory that RBG with monoclonal Mott cells is a benign condition. However, Fujiyoshi et al[2] described a gastric tumor consisting of monoclonal Mott cells which metastasized to the perigastric lymph nodes, and they concluded that the gastric tumor was most likely an extramedullary plasmacytoma or a MALT lymphoma. Joo[3] and Kai et al[36] also showed that monoclonal Mott cells can be a neoplastic component of MALT lymphoma with extreme plasmacytoid differentiation. Fujiyoshi et al[2], Joo[3], and Kai et al[36] did not describe cellular atypia or mitotic activity in monoclonal Mott cells in their cases, and therefore the histopathological distinction of monoclonal Mott cells in RBG and in MALT lymphoma and plasmacytoma remains unknown. In the present case, we concluded that the monoclonal Mott cells were non-neoplastic cells mainly because of the absence of cellular atypia and mitotic activity. Nevertheless, future studies are warranted to clarify the distinction between RBG with monoclonal Mott cells and MALT lymphoma or plasmacytoma.

In conclusion, we presented an unusual case of an 86-year-old man with H. pylori-positive RBG. This is a valuable case of RBG evaluated by M-NBI and pathological evaluation of the entire lesion. The detailed endoscopic evaluation led to the clinical diagnosis of a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, despite the fact that previous endoscopically diagnosed cases of RBG were exclusively inflammatory. Pathological evaluation of ESD-obtained specimens confirmed the presence of regional proliferation of kappa-restricted Mott cells within the mucosal lesion and failed to identify an epithelial malignancy. RBG is a rare condition whose incidence is expected to increase in proportion to the increased use of M-NBI. Therefore, it is of great clinical importance to increase our understanding of the pathological features of RBG in order to effectively diagnose and manage future cases.

We thank Ms. Keiko Mizuno, Mr. Masahiko Ohara, Ms. Yukari Wada, Ms. Yoshiko Agatsuma, and Ms. Kaori Yasuoka for preparing the histological and immunohistochemical specimens.

An 86-year-old Japanese man with melena and a history of rheumatoid arthritis and type 2 diabetes mellitus.

The patient was initially diagnosed with atrophic and erosive gastritis secondary to Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, and the first esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed a 13-mm flat lesion of white and slightly brown discoloration in the lesser curvature of the antrum.

Findings of magnification endoscopy with a narrow-band imaging (M-NBI) of the flat gastric lesion suggested poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma.

Laboratory findings revealed anemia and a positive serum anti-H. pylori antibody test.

M-NBI of the lesion showed loss or irregularity of microsurface pattern, irregular microvascular proliferation, and a demarcation line, which suggested poorly differentiated early gastric cancer.

The final diagnosis was Russell body gastritis (RBG) with substantial infiltration of granulated plasma cells. Although the granulated plasma cells showed kappa light chain restriction and the presence of Dutcher bodies, malignant lymphoma was unlikely partly because of the paucity of the cellular atypia and mitotic activity.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) was selected for therapeutic diagnosis.

Thirty-one previously published cases of RBG, including the authors own, has been reported, and this is the first reported case of RBG with the endoscopic diagnosis of malignant tumor with M-NBI, pathological evaluation of the entire lesion with ESD-obtained specimens, and the presence of Dutcher bodies.

RBG is considered as a unique form of chronic gastritis characterized by infiltration of plasma cells filled with spherical eosinophilic cytoplasmic globules, referred to as Russell bodies.

The endoscopic features of RBG are exclusively inflammatory; however, clinicians should consider RBG as a differential diagnosis in cases where detailed endoscopic examination reveals poorly differentiated early gastric cancer. Pathologists should be aware of the existence of this pathological entity, because histological features of RBG can overlap with those of malignant lymphoma.

Excellent case report article.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Lu XL, Souza JLS, Tsukamoto T S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Tazawa K, Tsutsumi Y. Localized accumulation of Russell body-containing plasma cells in gastric mucosa with Helicobacter pylori infection: ‘Russell body gastritis’. Pathol Int. 1998;48:242-244. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Fujiyoshi Y, lnagaki H, Tateyama H, Murase T, Eimoto T. Mott cell tumor of the stomach with Helicobacter pylori infection. Pathol Int. 2001;51:43-46. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Joo M. Gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma masquerading as Russell body gastritis. Pathol Int. 2015;65:396-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Russell W. An Address on a Characteristic Organism of Cancer. Br Med J. 1890;2:1356-1360. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Gray A, Doniach I. Ultrastructure of plasma cells containing Russell bodies in human stomach and thyroid. J Clin Pathol. 1970;23:608-612. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Matthews JB. The immunoglobulin nature of Russell bodies. Br J Exp Pathol. 1983;64:331-335. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Ribourtout B, Zandecki M. Plasma cell morphology in multiple myeloma and related disorders. Morphologie. 2015;99:38-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Erbersdobler A, Petri S, Lock G. Russell body gastritis: an unusual, tumor-like lesion of the gastric mucosa. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:915-917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Araki D, Sudo Y, Imamura Y, Tsutsumi Y. Russell body gastritis showing IgM kappa-type monoclonality. Pathol Int. 2013;63:565-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ensari A, Savas B, Okcu Heper A, Kuzu I, Idilman R. An unusual presentation of Helicobacter pylori infection: so-called “Russell body gastritis”. Virchows Arch. 2005;446:463-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Drut R, Olenchuk AB. Images in pathology. Russell body gastritis in an HIV-positive patient. Int J Surg Pathol. 2006;14:141-142. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Paik S, Kim SH, Kim JH, Yang WI, Lee YC. Russell body gastritis associated with Helicobacter pylori infection: a case report. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:1316-1319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wolkersdörfer GW, Haase M, Morgner A, Baretton G, Miehlke S. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and Russell body formation in Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Helicobacter. 2006;11:506-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pizzolitto S, Camilot D, DeMaglio G, Falconieri G. Russell body gastritis: expanding the spectrum of Helicobacter pylori - related diseases? Pathol Res Pract. 2007;203:457-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Licci S, Sette P, Del Nonno F, Ciarletti S, Antinori A, Morelli L. Russell body gastritis associated with Helicobacter pylori infection in an HIV-positive patient: case report and review of the literature. Z Gastroenterol. 2009;47:357-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tabata S, Taguchi S, Noriki S. Russell body gastritis: a care report. Gastroenterol Endosc. 2010;52:2927-2932. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Habib C, Gang DL, Ghaoui R, Pantanowitz L. Russell body gastritis. Am J Hematol. 2010;85:951-952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Miura S, Shirahama K, Sakaguchi M, Takao M, Hirakawa T, Nishihara M, Shimada M, Oka H, Ishiguro S. [Russell body gastritis]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2012;109:929-935. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Yoon JB, Lee TY, Lee JS, Yoon JM, Jang SW, Kim MJ, Lee SJ, Kim TO. Two Cases of Russell Body Gastritis Treated by Helicobacter pylori Eradication. Clin Endosc. 2012;45:412-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Choi J, Lee HE, Byeon S, Nam KH, Kim MA, Kim WH. Russell body gastritis presented as a colliding lesion with a gastric adenocarcinoma: A case report. Basic Applied Pathol. 2012;5:54-57. |

| 21. | Karabagli P, Gokturk HS. Russell body gastritis: case report and review of the literature. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2012;21:97-100. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Coyne JD, Azadeh B. Russell body gastritis: a case report. Int J Surg Pathol. 2012;20:69-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zhang H, Jin Z, Cui R. Russell body gastritis/duodenitis: a case series and description of immunoglobulin light chain restriction. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2014;38:e89-e97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Klair JS, Girotra M, Kaur A, Aduli F. Helicobacter pylori-negative Russell body gastritis: does the diagnosis call for screening for plasmacytic malignancies, especially multiple myeloma? BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:bcr2013202672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Muthukumarana V, Segura S, O’Brien M, Siddiqui R, El-Fanek H. “Russell Body Gastroenterocolitis” in a Posttransplant Patient: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Int J Surg Pathol. 2015;23:667-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Del Gobbo A, Elli L, Braidotti P, Di Nuovo F, Bosari S, Romagnoli S. Helicobacter pylori-negative Russell body gastritis: case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1234-1236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Saraggi D, Battaglia G, Guido M. Russell body carditis. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Wolf EM, Mrak K, Tschmelitsch J, Langner C. Signet ring cell cancer in a patient with Russell body gastritis--a possible diagnostic pitfall. Histopathology. 2011;58:1178-1180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Nishimura N, Mizuno M, Shimodate Y, Doi A, Mouri H, Matsueda K, Yamamoto H, Notohara K. Russell Body Gastritis Treated With <i>Helicobacter pylori</i> Eradication Therapy: Magnifying Endoscopic Findings With Narrow Band Imaging Before and After Treatment. ACG Case Rep J. 2016;3:e96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Soltermann A, Koetzer S, Eigenmann F, Komminoth P. Correlation of Helicobacter pylori virulence genotypes vacA and cagA with histological parameters of gastritis and patient’s age. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:878-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Brink T, Wagner B, Gebbers JO. Monoclonal plasma and Mott cells in a rectal adenoma. Histopathology. 1999;34:81-82. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Wündisch T, Neubauer A, Stolte M, Ritter M, Thiede C. B-cell monoclonality is associated with lymphoid follicles in gastritis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:882-887. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Johnsen SJ, Berget E, Jonsson MV, Helgeland L, Omdal R, Jonsson R. Evaluation of germinal center-like structures and B cell clonality in patients with primary Sjögren syndrome with and without lymphoma. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:2214-2222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Saxena A, Alport EC, Moshynska O, Kanthan R, Boctor MA. Clonal B cell populations in a minority of patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:1258-1263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Pozzato G, Burrone O, Baba K, Matsumoto M, Hijiiata M, Ota Y, Mazzoran L, Baracetti S, Zorat F, Mishiro S. Ethnic difference in the prevalence of monoclonal B-cell proliferation in patients affected by hepatitis C virus chronic liver disease. J Hepatol. 1999;30:990-994. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Kai K, Miyahara M, Tokuda Y, Kido S, Masuda M, Takase Y, Tokunaga O. A case of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract showing extensive plasma cell differentiation with prominent Russell bodies. World J Clin Cases. 2013;1:176-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |