Published online May 16, 2017. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v9.i5.220

Peer-review started: October 9, 2016

First decision: December 13, 2016

Revised: December 22, 2016

Accepted: February 28, 2017

Article in press: March 2, 2017

Published online: May 16, 2017

Processing time: 222 Days and 3.9 Hours

To identify factors differentiating pathologic adult intussusception (AI) from benign causes and the need for an operative intervention. Current evidence available from the literature is discussed.

This is a case series of eleven patients over the age of 18 and a surgical consultation for “Intussusception” at a single veteran’s hospital over a five-year period (2011-2016). AI was diagnosed on computed tomography (CT) scan and or flexible endoscopy (colonoscopy). Surgical referrals were from the emergency room, endoscopy suites and the radiologists.

A total of 11 cases, 9 males and 2 females were diagnosed with AI. Median age was 58 years. Abdominal pain and change in bowel habits were most common symptoms. CT scan and or colonoscopy diagnosed AI, in ten/eleven (90%) patients. There were 6 small bowel-small bowel, 4 ileocecal, and 1 sigmoid-rectal AI. 8 patients (72%) needed an operation. Bowel resection was required and definitive pathology was diagnosed in 7 patients (63%). Five patients had malignant and 2 patients had benign etiology. Small bowel enteroscopy excluded pathology in 4 cases (37%) with AI. Younger patients tend to have a benign diagnosis.

Majority of AI have malignant etiology however idiopathic intussusception is being seen more frequently. Operative intervention remains the mainstay however, certain small bowel intussusception especially in younger patients may be a benign, physiological, transient phenomenon and laparoscopy with reduction or watchful waiting may be an acceptable strategy. These patients should undergo endoscopic or capsule endoscopy to exclude intrinsic luminal lesions.

Core tip: In the current era with advances in diagnostic imaging techniques and overutilization of computed tomography, idiopathic or asymptomatic intussusception is being seen more commonly. The majority of adult intussusceptions however, have pathologic etiology. Patients with palpable mass, obstruction, gastrointestinal bleeding, or a lead point on computed tomography should undergo operative exploration. Certain small bowel intussusception may have a benign, physiological cause and laparoscopy with reduction may be an acceptable strategy. However these patients should undergo small bowel enteroscopy or capsule endoscopy if not obstructed to exclude luminal lesions. All colonic intussusceptions should be resected en-bloc without reduction, whereas a more selective approach may be applied for entero-enteric intussusceptions.

- Citation: Shenoy S. Adult intussusception: A case series and review. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 9(5): 220-227

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v9/i5/220.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v9.i5.220

Intussusception is an infrequent cause of bowel obstruction in adults compared to pediatric age group[1]. Any focus of an intraluminal irritant such as inflamed mucosa or a mass lesion may act as a lead point and the resulting hyperperistaltic activity causes a segment of bowel (intussusceptum) possibly along with its mesentery to telescope into the adjacent distal bowel lumen (intussuscipiens). Adult intussusception is classified according the location of the lead point as entero-enteric, ileocolic, ileocecal, and colo-colic.

Ninety percent of adult intussusception (AI) patients harbor a pathological process. In contrast majority of pediatric patients have a benign or physiologic diagnosis[2]. In the pediatric population non-surgical therapies such as pneumatic or hydrostatic reductions is sufficient to treat this condition in 80% of patients. Surgical management remains the mainstay treatment modality for a majority of patients with AI.

The frequent use of abdominal computed tomography (CT) scans for abdominal imaging has led to increased detection of small bowel intussusception which may be a benign, physiological, transient phenomenon with no apparent underlying disease[3]. With the advances made in three dimensional CT scans, flexible endoscopy, enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy, surgical exploration and bowel resection may not be necessary in all AI and surgical treatment should be tailored to individual patients. The present study reviews our experience of this clinical entity.

This is a case series of eleven patients over the age of 18 with a surgical consultation for “Intussusception” at a single veteran’s hospital over a five year period (2011-2016). These patients were diagnosed with AI on various modes of investigation such as CT scan and or flexible endoscopy (colonoscopy). These surgical referrals were from the emergency room, endoscopy suites and the radiologists. There were no exclusion criteria. We specifically aimed to identify factors which will differentiate pathological from benign causes, such as age, sex, prior operations, and malignancy. The clinical features, diagnostic studies, surgical findings, surgical techniques, final pathology and surgical follow up were reviewed from the medical charts and are discussed. An electronic search of PubMed, Medline was performed; the search terms used were intussusception, adults, bowel obstruction. The references from the retrieved literature were further searched for relevant studies.

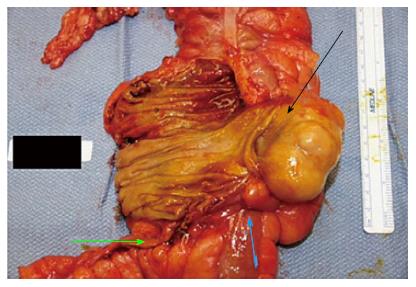

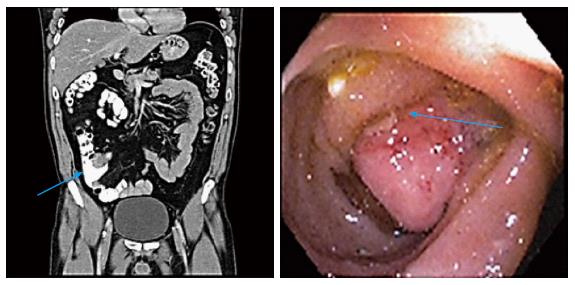

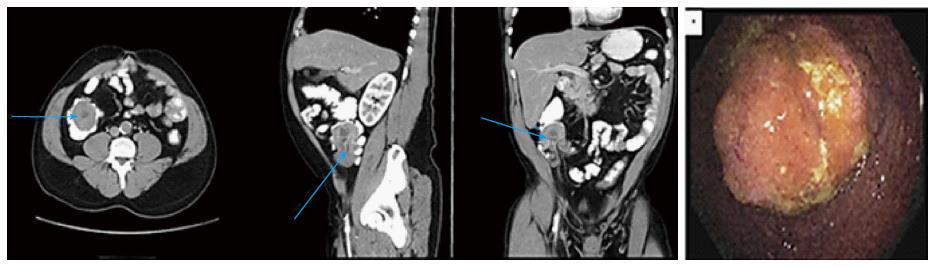

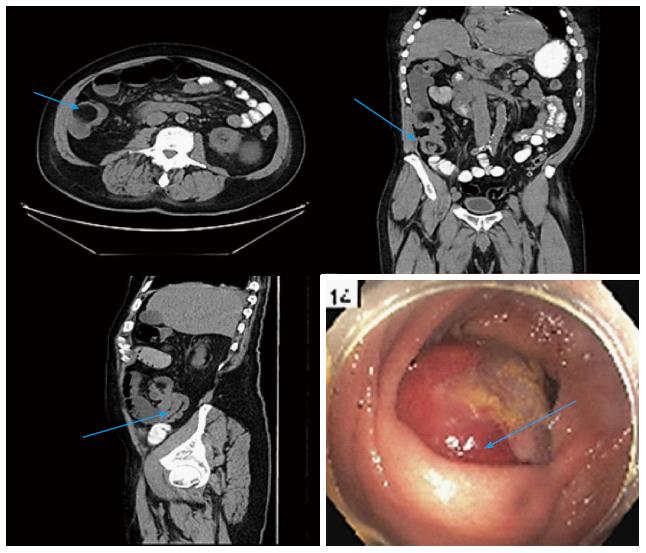

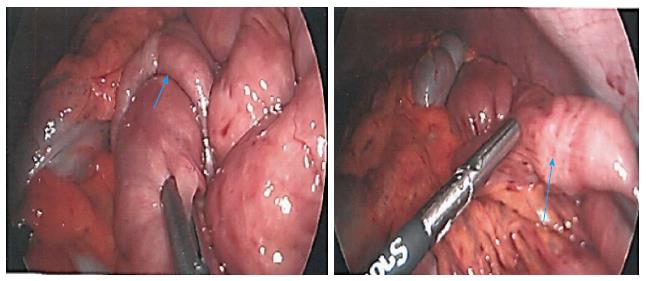

A total of 11 patients with a diagnosis of AI were identified from surgical consultation database with a diagnosis of intussusception (Table 1, Figures 1-5). There were 9 males and 2 females. The median age at diagnosis was 58 years. with a range of 26-74 years. Coincidently none of these 11 patients had prior abdominal operations. A single patient had a prior history of malignancy (lung). Abdominal pain was the most common presenting symptom (80%). Changes in the bowel pattern (constipation/diarrhea) were other symptoms (50%). Three patients (27%) presented with acute small bowel obstruction. Acute gastrointestinal tract bleeding was present in two patients (18%) and one patient (9%) was asymptomatic with jejunal intussusception as an incidental finding diagnosed on the CT scan. None of the patients had anemia, or familial syndromes such as familial adenomatosis polyposis (FAP), juvenile polyposis syndrome, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, or Lynch syndrome to suggest increased risk for small and large bowel malignancy.

| Case sex/age (yr) | Presentation | Classification | Diagnostic modality | Operation | Pathology | Follow up months | Lead point |

| Case 1 F/65 | Chronic abdominal pain | Ileocecal | Colonoscopy | Right hemicolectomy | Lipoma | 65 | Ileocecal valve (Figure 1) |

| Case 2 M/54 | Chronic abdominal pain | Ileocecal | Colonoscopy | Right hemicolectomy | Terminal ileal carcinoid | 25 | Terminal ileum (Figure 2) |

| Case 3 M/65 | Acute small bowel obstruction | Jejunal-Jejunal | CT scan | Small bowel resection | Metastatic lung cancer | 27 | Jejunal |

| Case 4 M/50 | Incidental finding | Jejunal- Jejunal | CT scan, small bowel enteroscopy | None | Idiopathic | 14 | None |

| Case 5 M/58 | GI bleeding | Ileocecal | Colonoscopy | Right hemicolectomy | Tubulo-villous adenoma | 16 | Ileocecal valve (Figure 3) |

| Case 6 M/74 | Partial small bowel obstruction | Ileocecal | CT scan and colonoscopy | Right hemicolectomy | GIST | 6 | Terminal ileum (Figure 4) |

| Case 7 M/63 | Acute small bowel obstruction | Ileal-ileal | Laparotomy | Small bowel resection | Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma | 6 | Mid ileum |

| Case 8 M/26 | Acute small bowel obstruction | Jejunal-jejunal | CT scan and laparoscopy | Laparoscopy and reduction | Idiopathic/H. pylori duodenitis | 5 | None (Figure 5) |

| Case 9 F/38 | Chronic abdominal pain | Jejuno-jenunal | CT scan, small bowel enteroscopy | None | Idiopathic/H. pylori duodenitis | 4 | None |

| Case 10 M/66 | GI bleeding | Sigmoid-rectal | Colonoscopy | Low anterior resection | Adenocarcinoma | 3 | Sigmoid |

| Case 11 M/58 | Abdominal pain | Jejunal-jejunal | CT scan, small bowel enteroscopy | None | Idiopathic | 2 | None |

CT scan was the most frequently used diagnostic imaging test and identified AI in nine/eleven (81%) patients. It confirmed a mass lesion in seven/eleven (63%) patients, and diagnosed obstruction in three/eleven (27%) patients. Colonoscopy was performed on five/eleven patients and diagnosed AI in one patient. It however confirmed a mass in all five patients and permitted a biopsy which assisted with a definitive operative planning. The diagnosis of AI was made preoperatively in ten/eleven (90%) patients with the above modalities.

Small bowel enteroscopy (SBE) was performed on four/eleven patients. It was primarily chosen in three patients for patients who had a non-operative conservative care with resolution of symptoms and one patient after diagnostic laparoscopy. These patients were in a younger age group and had a low index of suspicion for a pathological diagnosis. SBE was performed to exclude any intraluminal small bowel pathology and to confirm the transient, physiological cause for AI in these patients. All four patients had a normal SBE exam and therefore these patients were diagnosed as idiopathic AI.

Six (54%) patients had a lead point of the intussusception (one in the small bowel, four at the ileocecal region, and one sigmoid-rectal). Total of eight patients (72%) needed an operation. Three of the operated eight patients presented with acute intestinal obstruction and underwent emergency operation (37.5%). The rest five patients were operated on an elective basis.

Laparotomy in seven/eight (87.5%) and a diagnostic laparoscopy in one/eight (12.5%) were performed. Multiple jejunal-jejunal AI was observed in this last patient (case 8; Table 1) and laparoscopic reduction was performed without bowel resection. A subsequent small bowel enteroscopy ruled out an intrinsic lesion. In the laparotomy group four/eight patients had a right hemicolectomy due to ileocecal mass, two patients had small bowel resection and one had a low anterior resection for a malignant mass.

In three/eleven patients with subacute presentation, pathologic AI and intraluminal pathology was excluded with a small bowel enteroscopy thus avoiding an operation. There were six entero-enteric, four ileocecal, and one sigmoid-rectal AI. Ileocecal and colo-colic AI had a definitive pathology, while most jejuno-jejunal AI was transient and physiologic. The location, pathology, extent of surgery and follow up are presented in Table 1.

A definitive pathologic diagnosis was seen in seven/eleven (64%) patients. Of these cases five (46%) had malignant etiology and two (18%) had benign etiology. Four patients had no abnormality and were idiopathic (36%). Two of these four patients tested positive for H. pylori duodenitis on small bowel enteroscopy. This was probably an incidental finding. There were no significant post-operative morbidities or thirty day mortality.

The mean follow up was 15 mo, range 2-65 mo. Ninety percent of the patients were alive and only one patient with poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of ileum succumbed to his disease.

AI is a rare finding and an unusual cause of bowel obstruction. They are an infrequent cause in adult patients although common in pediatric population. It represents 1% of all bowel obstructions in adults and 5% of all intussusceptions[1].

Although pathologic in most instances, 20% of patients have no apparent etiology and are labelled as primary or idiopathic. Idiopathic AI is more likely to occur in the small intestine[1,2,4]. The majority of secondary AI have a lead point (Table 2). Most lead points in the small intestines are of benign etiology and comprises of inflammatory polyps, lipomas, leiomyoma, Meckel’s diverticulum and post-operative adhesions[5-7]. Patient with Crohn’s disease and celiac disease are known to present with transient AI of small bowel and generally manifest as a non-lead point intussusception[3,8]. Malignant lesions include primary tumors such as carcinoids, adenocarcinoma, malignant polyps, gist’s, leiomyosarcomas, lymphoma and metastatic tumors, most commonly melanoma[2,9-11]. Majority of AI involving the ileocecal region and large bowel have a malignant etiology[1,12,13]. In a large multicenter study of forty four patients with AI, 37% with small bowel and 58% with colonic AI were malignant[14]. Abdominal pain is the most common symptom of AI, followed by change in bowel habits, nausea and vomiting, gastrointestinal bleeding. The majority of adult patients have chronic abdominal symptoms consistent with chronic partial small bowel obstruction.

| Benign | Malignant | |

| Primary | Metastatic | |

| Crohns disease | Adenocarcinoma | Melanoma |

| Celiac disease | Gastrointestinal stromal tumor | Lung |

| Lipoma | Carcinoids | Renal cell cancer |

| Leiomyoma | Leiomyosarcomas | Breast |

| Neurofibromatosis | Lymphoma | |

| Fibro-epithelial polyps | ||

| Henoch-Schonlein purpura | ||

| Human immunodeficiency virus | ||

| Post-operative adhesions | ||

| Endometriosis | ||

| Meckel’s diverticulum | ||

A contrasted CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis is the most sensitive imaging modality to detect intussusception. Characteristic features include a soft tissue mass, target or sausage shaped, enveloped with an eccentrically located area of low density. Findings of a bowel within bowel configuration with or without mesenteric fat and mesenteric vessels are pathognomonic for intussusception[3]. CT scans also provides other critical information such as length and diameter of the intussusception, three dimensional views of the bowel and surrounding viscera, possible lead point, type of and location of intussusception, the mesenteric vasculature, possibility of strangulation, and the likelihood of partial or complete bowel obstruction[15,16]. In general AI without a lead point is transient and may resolve spontaneously. Further if there is no associated bowel obstruction, these patients may not require an operation[3]. Our series had four patients with a CT diagnosis of intussusception without a lead point and a subsequent negative small bowel enteroscopy examination.

In a retrospective analysis of a large number of patients (170/380999, 0.04%) diagnosed with AI on the CT scan, demonstrated differences in length, diameter, lead point and bowel obstruction amongst the three categories of patients: (1) observed without operation; (2) without intussusception on exploration; and (3) with confirmed intussusception. In these study patients with CT scan findings of intussusception length less than 4 cm were more likely to respond to conservative management and have transient AI compared to patients with intussusception length of 9.6 cm. Similarly patients with an intussusception diameter of less than 3.2 cm were more likely to have transient AI compared to a diameter of greater than 4.8 cm in pathological AI. Finally patients with presence of a lead point AI and bowel obstruction had a fifty percent likelihood of pathologic AI.

The authors concluded that AI discovered by CT scanning does not always mandate exploration. Most cases can be treated expectantly despite the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms. Close follow up was recommended with imaging and endoscopic surveillance[17].

Another retrospective study of CT scan in diagnosing pathologic intussusception suggested length of intussusception shorter than 3.5 cm as likely to be transient, self-limiting. However there was a lack of pathological correlation in this study[18].

Abdominal ultrasonography has been a useful technique in the diagnosis of AI[19]. The features described include a target and doughnut signs on the transverse view and a pseudo kidney sign on a longitudinal view[20,21]. Ultrasonography carries no radiation risks and is readily available; however in our opinion the test is operator dependent and requires an experienced examiner. Further limitations include obesity and bowel gas which may obscure the typical findings and information on mesenteric vasculature, location and surrounding viscera is not clearly defined. It may however play a role in self-limiting, transient AI as seen in celiac disease and Crohn’s disease to monitor resolution of intussusception and thus avoiding repeated CT scans and exposure to radiation[19].

Flexible endoscopy including colonoscopy and small bowel enteroscopy may be a useful diagnostic tool in patients with subacute or chronic intermittent bowel obstruction[22,23]. It permits the confirmation of the intussusception, location and biopsy to aid with the diagnosis and plan surgery[24]. Colonoscopy is most useful for AI involving the colon and the terminal ileum and cecum[25]. Small lesions can be snared endoscopically if the surrounding bowel appears normal without signs of inflammation or ischemia, however lesions larger than 2 cm with a wide base should not excised due to increased risk of perforation of the bowel[6]. In our series colonoscopy was performed in five patients and confirmed a mass in all five cases. Small bowel enteroscopy was used in four patients and was able to rule out an intrinsic lesion, thus preventing an operation in three patients and bowel resection in the third. Flexible endoscopy should be avoided in patients with acute obstruction as it may increase the risk for perforation[26].

Ninety percent of AI patients harbor a pathological process[1,14]. Surgical management remains the mainstay treatment modality for a majority of patients with AI. Surgical decision making and the extent of resection depends upon factors such as presence of acute bowel obstruction with jeopardized mesentery, the probability of a malignant etiology, the location of the intussusception[27]. Before the advent of diagnostic modalities, immediate laparotomy and bowel resection without reduction was the standard of care and advocated by most surgeons[1,12,28]. The current controversy remains on the extent of surgical resection vs reduction of the intussusception. The initial favor to resect en-bloc the intussuscepted segment of bowel was based on the theoretical risks of venous embolization of the tumor cells on bowel manipulation and also the risks of perforating the ischemic, friable, edematous bowel which may lead to seeding of tumor cells and microorganisms into the peritoneal cavity[1,29]. However it lacks supportive evidence as most of the literature is based on case reports, series and anecdotal evidence. Certain authors have questioned these hypothesis and selective criteria for reduction and resection have been proposed[27,30].

Our experience suggests a more conservative approach to AI. Only three patients in our series presented with acute bowel obstruction, confirmed on the CT scan and required an immediate operation. Two of these patients required small bowel resection and one patient had intussusception reduced. This last patient subsequently had a small bowel enteroscopy followed by a capsule endoscopy and no intraluminal lesion was discovered labelling it as idiopathic. Five patients with intermittent chronic partial small bowel obstruction and GI tract bleeding had further diagnostic tests such as colonoscopy, small bowel enteroscopy and a CT scan. This provided us with an opportunity to complete workup, stage the patients and administer bowel preparation for a planned definitive surgical resection. Small bowel enteroscopy in three patients with jejunal-jejunal intussusception excluded intraluminal lesions and no operation was performed in these patients. The AI resolved in the subsequent scans in these three patients and they remain symptom free.

Small bowel intussusception may be reduced intraoperatively only in patients in whom a benign diagnosis or medically treatable diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease is strongly suggested preoperatively, and in patients in whom resection may result in short gut syndrome[4,13,31-33]. In addition we recommend a follow up small bowel enteroscopy and or a capsule endoscopy in these idiopathic, non-obstructed patients to exclude any intrinsic luminal lesions which may lead to recurrent intussusception.

We agree with other authors that colonic lesions should be resected without reduction as most of these could harbor a pathologic etiology and may not respond to conservative management[14,25,34,35].

Any AI with signs of mesenteric vasculature compromise, strangulation, severe bowel edema, complete bowel obstruction and elevated white blood cell counts should undergo segmental resection as the risks for perforation with contamination of the peritoneal cavity remains high[36,37].

Diagnostic laparoscopy and resection has been used successfully in selected patients with AI. In patients with chronic and subacute presentation with partial small bowel obstruction, laparoscopy offers the benefit of a conservative approach with possible reduction of the bowel and provides clues to the etiology[38]. In a series of 12 patients with AI, laparoscopic diagnosis and resection was accomplished safely without significant morbidity or mortality[39]. Another series reported eight patients with AI where laparoscopy with reduction and resection was performed without any complications or conversions. The laparoscopic approach thus offers both a diagnostic, and a therapeutic option for intussusception in adults[40]. However we urge caution in using laparoscopy in acutely obstructed patients with bowel distension where visualization may be poor, and bowel manipulation may further risk perforation and increase the morbidity of an operation.

In general, preoperative probability of harboring a malignancy is higher in patients older than sixty years, previous history of malignancy such as melanoma, lung cancers, and patients with genetic risks for small bowel malignancy such as FAP, Lynch syndrome, chronic long standing history of Crohn’s disease and celiac disease[41]. Reduction should not be attempted in these patients as malignancy may be difficult to confirm or exclude intraoperatively. Bowel resection is recommended for this subset of patients. Patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome are predisposed to multiple small bowel polyps which may frequently cause intussusception. A combined surgical and endoscopic approach can assess the extent of the polyposis, and small polyps can be removed by snare polypectomy. This may prevent multiple laparotomies and resections reducing the risk of short bowel syndrome[42].

In the current era with advances in diagnostic imaging techniques and overutilization of computed tomography, idiopathic or asymptomatic intussusception is being seen more commonly. The majority of adult intussusceptions however, have pathologic etiology. Patients with palpable mass, obstruction, gastrointestinal bleeding, or a lead point on computed tomography should undergo operative exploration. Certain small bowel intussusception especially in younger patients may have a benign, physiological cause and laparoscopy with reduction may be an acceptable strategy. However these patients should undergo small bowel enteroscopy or capsule endoscopy if not obstructed to exclude intraluminal lesions. All colonic intussusceptions should be resected en-bloc without reduction, whereas a more selective approach may be applied for entero-enteric intussusceptions.

Our series has limitations for being a retrospective study and with small volume. There is a potential for selection and referral bias. Because of rarity of the outcome, the study may be underpowered. However as mentioned AI is a rare finding and clinical presentation and acuity should determine the operative decision making vs conservative care with a close follow up.

In the current era with advances in diagnostic imaging techniques and overutilization of computed tomography, idiopathic or asymptomatic intussusception is being seen more commonly. The majority of adult intussusceptions however, have pathologic etiology. Certain small bowel intussusception especially in younger patients may have a benign, physiological cause and laparoscopy with reduction may be an acceptable strategy.

Small bowel enteroscopy or capsule endoscopy are important diagnostic tools in evaluating patients with small bowel intussusceptions which in many younger patients may be a physiologic, normal peristalsis. This is especially useful if patients do not present with obstruction, to exclude intraluminal lesions. Further research is needed to elucidate the role of these diagnostic modalities.

Small bowel adult intussusception (AI) discovered by computed tomography scanning does not always mandate exploration. Most cases can be treated expectantly despite the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms. Close follow is recommended with imaging and endoscopic surveillance. However patients with palpable mass, obstruction, gastrointestinal bleeding, or a lead point on computed tomography should undergo operative exploration.

Flexible endoscopy including colonoscopy and small bowel enteroscopy may be a useful diagnostic tool in patients with subacute or chronic intermittent bowel obstruction. It permits the confirmation of the intussusception, location and biopsy to aid with the diagnosis and plan surgery. Colonoscopy is most useful for AI involving the colon and the terminal ileum and cecum. Small lesions can be snared endoscopically if the surrounding bowel appears normal without signs of inflammation or ischemia, however lesions larger than 2 cm with a wide base should not excised due to increased risk of perforation of the bowel.

The author presents an interesting study and review on a less frequent but certainly relevant and important entity to gastrointestinal disease, surgery, and endoscopy.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Greenspan M, Allaix ME S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Azar T, Berger DL. Adult intussusception. Ann Surg. 1997;226:134-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 648] [Cited by in RCA: 666] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Erkan N, Haciyanli M, Yildirim M, Sayhan H, Vardar E, Polat AF. Intussusception in adults: an unusual and challenging condition for surgeons. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2005;20:452-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kim YH, Blake MA, Harisinghani MG, Archer-Arroyo K, Hahn PF, Pitman MB, Mueller PR. Adult intestinal intussusception: CT appearances and identification of a causative lead point. Radiographics. 2006;26:733-744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yalamarthi S, Smith RC. Adult intussusception: case reports and review of literature. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:174-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ludvigsson JF, Nordenskjöld A, Murray JA, Olén O. A large nationwide population-based case-control study of the association between intussusception and later celiac disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Marinis A, Yiallourou A, Samanides L, Dafnios N, Anastasopoulos G, Vassiliou I, Theodosopoulos T. Intussusception of the bowel in adults: a review. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:407-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 428] [Cited by in RCA: 507] [Article Influence: 31.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Choi YS, Suh JP, Lee IT, Kim JK, Lee SH, Cho KR, Park HJ, Kim DS, Lee DH. Regression of giant pseudopolyps in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:240-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Knowles MC, Fishman EK, Kuhlman JE, Bayless TM. Transient intussusception in Crohn disease: CT evaluation. Radiology. 1989;170:814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shenoy S, Cassim R. Metastatic melanoma to the gastrointestinal tract: role of surgery as palliative treatment. W V Med J. 2013;109:30-33. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Zubaidi A, Al-Saif F, Silverman R. Adult intussusception: a retrospective review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1546-1551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shenoy S. Small Bowel Metastases: Tumor Markers for Diagnosis and Role of Surgical Palliation. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2016;47:210-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sanders GB, Hagan WH, Kinnaird DW. Adult intussusception and carcinoma of the colon. Ann Surg. 1958;147:796-804. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Eisen LK, Cunningham JD, Aufses AH. Intussusception in adults: institutional review. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188:390-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 243] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Barussaud M, Regenet N, Briennon X, de Kerviler B, Pessaux P, Kohneh-Sharhi N, Lehur PA, Hamy A, Leborgne J, le Neel JC. Clinical spectrum and surgical approach of adult intussusceptions: a multicentric study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21:834-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gore RM, Silvers RI, Thakrar KH, Wenzke DR, Mehta UK, Newmark GM, Berlin JW. Bowel Obstruction. Radiol Clin North Am. 2015;53:1225-1240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gayer G, Apter S, Hofmann C, Nass S, Amitai M, Zissin R, Hertz M. Intussusception in adults: CT diagnosis. Clin Radiol. 1998;53:53-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rea JD, Lockhart ME, Yarbrough DE, Leeth RR, Bledsoe SE, Clements RH. Approach to management of intussusception in adults: a new paradigm in the computed tomography era. Am Surg. 2007;73:1098-1105. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Lvoff N, Breiman RS, Coakley FV, Lu Y, Warren RS. Distinguishing features of self-limiting adult small-bowel intussusception identified at CT. Radiology. 2003;227:68-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kralik R, Trnovsky P, Kopáčová M. Transabdominal ultrasonography of the small bowel. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:896704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Weissberg DL, Scheible W, Leopold GR. Ultrasonographic appearance of adult intussusception. Radiology. 1977;124:791-792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | del-Pozo G, Albillos JC, Tejedor D. Intussusception: US findings with pathologic correlation--the crescent-in-doughnut sign. Radiology. 1996;199:688-692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Potts J, Al Samaraee A, El-Hakeem A. Small bowel intussusception in adults. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2014;96:11-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rahimi E, Guha S, Chughtai O, Ertan A, Thosani N. Role of enteroscopy in the diagnosis and management of adult small-bowel intussusception. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:863-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Elena RM, Riccardo U, Rossella C, Bizzotto A, Domenico G, Guido C. Current status of device-assisted enteroscopy: Technical matters, indication, limits and complications. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;4:453-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gupta RK, Agrawal CS, Yadav R, Bajracharya A, Sah PL. Intussusception in adults: institutional review. Int J Surg. 2011;9:91-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | El-Sergany A, Darwish A, Mehta P, Mahmoud A. Community teaching hospital surgical experience with adult intussusception: Study of nine cases and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;12:26-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Honjo H, Mike M, Kusanagi H, Kano N. Adult intussusception: a retrospective review. World J Surg. 2015;39:134-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Brayton D, Norris WJ. Intussusception in adults. Am J Surg. 1954;88:32-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Begos DG, Sandor A, Modlin IM. The diagnosis and management of adult intussusception. Am J Surg. 1997;173:88-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 365] [Cited by in RCA: 384] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Nagorney DM, Sarr MG, McIlrath DC. Surgical management of intussusception in the adult. Ann Surg. 1981;193:230-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Takeuchi K, Tsuzuki Y, Ando T, Sekihara M, Hara T, Kori T, Kuwano H. The diagnosis and treatment of adult intussusception. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:18-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wang LT, Wu CC, Yu JC, Hsiao CW, Hsu CC, Jao SW. Clinical entity and treatment strategies for adult intussusceptions: 20 years’ experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1941-1949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Ongom PA, Opio CK, Kijjambu SC. Presentation, aetiology and treatment of adult intussusception in a tertiary Sub-Saharan hospital: a 10-year retrospective study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Yakan S, Caliskan C, Makay O, Denecli AG, Korkut MA. Intussusception in adults: clinical characteristics, diagnosis and operative strategies. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1985-1989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Hanan B, Diniz TR, da Luz MM, da Conceição SA, da Silva RG, Lacerda-Filho A. Intussusception in adults: a retrospective study. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:574-578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Reijnen HA, Joosten HJ, de Boer HH. Diagnosis and treatment of adult intussusception. Am J Surg. 1989;158:25-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Kim JS, Lim JH, Jeong JH, Kim WS. [Conservative management of adult small bowel intussusception detected at abdominal computed tomography]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2015;65:291-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Lin MW, Chen KH, Lin HF, Chen HA, Wu JM, Huang SH. Laparoscopy-assisted resection of ileoileal intussusception caused by intestinal lipoma. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2007;17:789-792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Palanivelu C, Rangarajan M, Senthilkumar R, Madankumar MV. Minimal access surgery for adult intussusception with subacute intestinal obstruction: a single center’s decade-long experience. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2007;17:487-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Siow SL, Mahendran HA. A case series of adult intussusception managed laparoscopically. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2014;24:327-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Shenoy S. Genetic risks and familial associations of small bowel carcinoma. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;8:509-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Lin BC, Lien JM, Chen RJ, Fang JF, Wong YC. Combined endoscopic and surgical treatment for the polyposis of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:1185-1187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |