Published online Oct 16, 2017. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v9.i10.514

Peer-review started: March 23, 2017

First decision: April 17, 2017

Revised: May 19, 2017

Accepted: July 14, 2017

Article in press: July 17, 2017

Published online: October 16, 2017

Processing time: 205 Days and 11.1 Hours

To evaluate the effectiveness of oral esomeprazole (EPZ) vs injectable omeprazole (OPZ) therapy to prevent hemorrhage after endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD).

A case-control study was conducted using a quasi-randomized analysis with propensity score matching. A total of 258 patients were enrolled in this study. Patients were treated with either oral EPZ or injectable OPZ. The endpoint was the incidence of hemorrhage after ESD.

Data of 71 subjects treated with oral EPZ and 172 subjects treated with injectable OPZ were analyzed. Analysis of 65 matched samples revealed no difference in the incidence of hemorrhage after ESD between the oral EPZ and injectable OPZ groups (OR = 0.89, 95%CI: 0.35-2.27, P ≥ 0.99).

We conclude that oral EPZ therapy is a useful alternative to injectable PPI therapy for the prevention of hemorrhage after ESD.

Core tip: Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) have been reported to be effective for suppressing hemorrhage after endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD); however, it remains unclear whether oral PPI therapy or injectable PPI therapy is preferable. The results of the present study indicate that oral effectiveness of oral esomeprazole therapy is a useful alternative to injectable PPI therapy for the prevention of hemorrhage after ESD.

- Citation: Uchiyama T, Higurashi T, Kuriyama H, Kondo Y, Hata Y, Nakajima A. Oral esomeprazole vs injectable omeprazole for the prevention of hemorrhage after endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 9(10): 514-520

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v9/i10/514.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v9.i10.514

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) allows en-bloc resection of even large and ulcerated gastric tumors[1,2]. It enables accurate histopathological diagnosis and reduces the risk of local recurrence[3], and is a standard treatment for selected gastric tumors. However, ESD is technically difficult and is associated with a higher risk of adverse events than conventional endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR)[3-5]. Among the adverse events, hemorrhage is a frequently encountered and serious problem[6]. Hemorrhage after ESD can occur at a later stage than other complications of ESD, such as perforation, sometimes occurring even after hospital discharge. Furthermore, hemorrhage after gastric ESD can be serious, as it can be massive and complicated by life-threatening hemorrhagic shock[7]. Thus, the importance of preventing hemorrhage after ESD cannot be overemphasized. While some previous studies have reported the risk factors for hemorrhage after ESD[6-14], no consensus has been arrived at yet in respect of the risk factors. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) have been reported to be effective for controlling hemorrhage after ESD[15]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there have been no studies yet to compare the efficacy of oral PPI therapy vs injectable PPI therapy for the control of hemorrhage after ESD. It remains unclear whether oral PPI therapy or injectable PPI therapy is preferable for the prevention of hemorrhage after ESD.

Esomeprazole (EPZ) is the S-isomer of omeprazole (OPZ) and has more favorable pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles than OPZ[16]. However, injectable EPZ is not available at present in our hospital. In the current study, therefore, we compared the efficacy of oral EPZ therapy with that of injectable OPZ (in place of EPZ) therapy for the prevention of hemorrhage after ESD by propensity score-matched analysis.

We conducted a retrospective study with propensity score-matched analysis. We registered patients who had undergone ESD for gastric tumors at our hospital between March 2008 and March 2014 (n = 258). The research protocol was approved by the Hospital Ethics Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from each of the participants of the study.

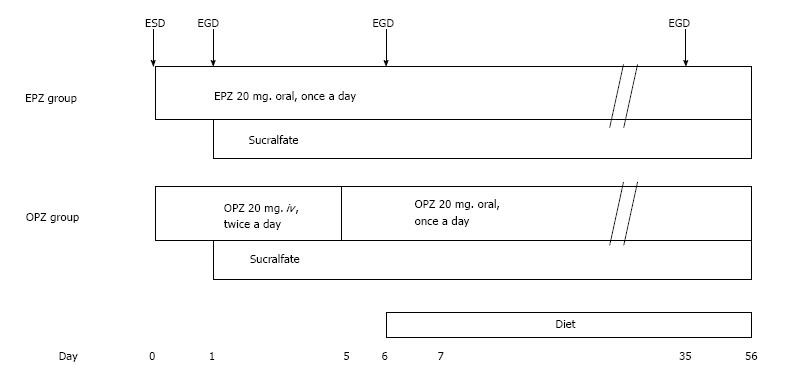

Figure 1 shows the treatment protocol used. The patients received either oral EPZ (20 mg daily) for 8 wk after ESD (oral EPZ group) or injectable OPZ (20 mg twice daily) for the first 5 d, followed by oral OPZ (20 mg daily) from day 6 to the end of 8 wk after the ESD (injectable OPZ group). Additionally, all the patients underwent an endoscopic examination on day 2 and a third endoscopy on day 6 after the ESD. All patients were given sucralfate from day 2 to the end of 8 wk after the ESD. Antiplatelet/anticoagulant drugs were discontinued before the ESD.

ESD was performed using a videoendoscope (GIF-Q260J), Electric scalpel for endoscopic surgery (IT-Knife2) (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and an electrosurgical unit (ICC 200) (ERBE Elektromedizin GmbH, Tubingen, Germany). After tumor resection, all the visible vessels in the created ulcer were coagulated using a coagulation device (Coagrasper) (Olympus Corporation).

Hemorrhage after ESD was defined as the presence of clinical evidence of hemorrhage, such as the occurrence of melena or hematemesis confirmed by the hospital staff, or confirmation of the presence of blood or bleeding spots in the post-ESD ulcer at the second or third endoscopy. Preventive hemostasis for visible vessels not showing evidence of hemorrhage during the second or third endoscopy was not included as evidence of hemorrhage after ESD. We also defined clinically significant hemorrhage after ESD as hemorrhage necessitating emergency endoscopy or blood transfusion.

Data are presented as mean ± SD or number, and the diagnostic outcomes were examined using the χ2 test. The variables and incidence of hemorrhage after ESD in the oral EPZ group were compared with those in the injectable OPZ group using the χ2 test. Furthermore, propensity score matching was performed to control and reduce the selective bias[17-19]. Ten variables that could potentially influence the incidence of hemorrhage after ESD, listed below, were used to generate propensity scores using logistic regression: Patient age, patient sex, history of use of antiplatelet/anticoagulant drugs, location of the lesion, lesion depth, presence/absence of ulceration, diameter of the lesion, duration of operation, macroscopic type of the lesion, and the operator experience (beginners: Surgeons who had performed < 50 gastric ESDs; experts: Surgeons who had performed > 50 gastric ESDs). A propensity score-matched cohort was created by trying to match each patient given oral EPZ with a patient given injectable OPZ (a 1:1 match), using the nearest pair method. After matching, a coarse comparison of the matched cohorts was performed using χ2 test. P values of < 0.05 were considered to indicate significance. Statistical analyses were performed using the JMP 10.0 software (SAS, North Carolina, United States).

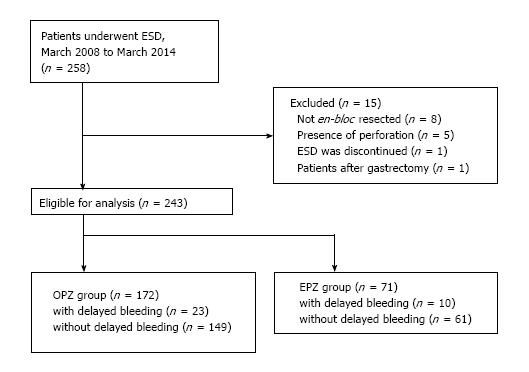

A total of 258 patients were enrolled in this study. Fifteen following reasons: Failure of resection of the lesion en-bloc (n = 8); presence of perforation (n = 5); interruption of the ESD (n = 1); previous history of gastrectomy (n = 1). Data of the remaining 243 patients were evaluated. Of the 243 patients, 172 who had undergone ESD before November 2012 received injectable OPZ, and the remaining 71 patients who had received ESD after November 2012 received oral EPZ (Figure 2). The data of 71 patients of the oral EPZ group and 172 patients of the injectable OPZ group were analyzed.

Among the 243 patients included in the analysis, 33 developed hemorrhage after the ESD (13.6%), with the hemorrhage being clinically significant in 10 of these cases (4.1%). Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the study population. A univariate analysis identified operator experience as the only risk factor for hemorrhage after ESD (beginner vs OR = 2.16; 95%CI: 1.03-4.55, P = 0.039). Hemorrhage after ESD was observed within 6 d of the procedure in all the cases.

| Hemorrhage after ESD | P value | ||

| Negative | Positive | ||

| Number | 210 | 33 | |

| Age (yr) | 73.9 ± 8.0 | 71.7 ± 9.4 | 0.14 |

| Gender (M/F) | 151/59 | 8/25 | 0.65 |

| Antiplatelet/anticoagulant drugs (-/+) | 161/49 | 8/25 | 0.91 |

| Hypertension (-/+) | 123/87 | 20/13 | 0.83 |

| Diabetes mellitus (-/+) | 186/24 | 4/27 | 0.52 |

| H. pylori infection (-/+) | 90/120 | 13/20 | 0.89 |

| Location (U/M/L) | 28/96/86 | 2/15/16 | 0.45 |

| Depth (m/sm) | 190/20 | 5/28 | 0.35 |

| Ulcer (-/+) | 205/5 | 33/0 | 0.37 |

| Diameter of the lesion (mm) | 40.7 ± 15.3 | 40.4 ± 13.9 | 0.89 |

| Duration of the operation (min) | 106.9 ± 64.1 | 123.8 ± 98.5 | 0.2 |

| Macroscopic type of the lesion (elevated or flat/combined/depressed) | 130/29/51 | 5/10/2018 | 0.49 |

| Pathological findings (Adenoma/Differentiated ca/Undifferentiated ca) | 76/126/8 | 12/21/0 | 0.32 |

| Lymphatic/venous invasion (-/+) | 206/4 | Jan-32 | 0.67 |

| Anastomosis (-/+) | 200/10 | 33/0 | 0.2 |

| Operator type (expert/beginner) | 129/81 | 14/19 | 0.0392 |

| Bleeding during ESD (good/poor control) | 164/46 | 9/24 | 0.49 |

A quasi-randomized experiment can be created using propensity score matching. That is, two subjects assigned to each group are equally likely to receive oral EPZ or injectable OPZ (Tables 2 and 3). Nearest-neighbor matches were performed using a caliper with 0.25 standard deviation of the propensity score (log odds scale). The predictive performance of the treatment model was evaluated using the χ2 statistic that can take values from 0.5 for chance prediction to 1.0 for perfect prediction[20]. The propensity score allowed clear distinction between cases with and without hemorrhage after ESD, with a c-statistic of 0.77.

| EPZ group | OPZ group | P value | |

| Number | 71 | 172 | |

| Age (yr) | 75.3 ± 7.1 | 72.9 ± 8.5 | 0.0361 |

| Gender (M/F) | 52/19 | 124/48 | 0.86 |

| Antiplatelet/anticoagulant drugs (-/+) | 50/21 | 136/36 | 0.15 |

| Hypertension (-/+) | 40/31 | 103/69 | 0.61 |

| Diabetes Mellitus (-/+) | Sep-62 | 151/21 | 0.92 |

| H. pylori infection (-/+) | 29/42 | 55/117 | 0.19 |

| Location (U/M/L) | 10/34/27 | 20/77/75 | 0.7 |

| Depth (m/sm) | 57/14 | 161/11 | 0.0019 |

| Ulcer (-/+) | 71/0 | 167/5 | 0.15 |

| Diameter of the lesion (mm) | 42.2 ± 17.2 | 40.14 ± 14.1 | 0.31 |

| Duration of the operation (min) | 115.9 ± 87.3 | 106.4 ± 61.1 | 0.34 |

| Macroscopic type of the lesion (elevated or flat/combined/depressed) | 46/16/9 | 102/18/52 | 0.003 |

| Pathological findings (Adenoma/Differentiated ca/Undifferentiated ca) | 26/42/3 | 62/105/5 | 0.86 |

| Lymphatic/venous invasion (-/+) | Jan-70 | 168/4 | 0.65 |

| Anastomosis (-/+) | Mar-68 | 163/9 | 0.74 |

| Operator type (expert/beginner) | 31/40 | 112/60 | 0.002 |

| Bleeding during ESD (good/poor control) | 55/16 | 134/38 | 0.94 |

| Hemorrhage after ESD (-/+) | 149/23 | Oct-61 | 0.88 |

| Clinically significant bleeding (-/+) | 165/7 | Mar-68 | 0.96 |

| EPZ group | OPZ group | P value | |

| Number | 65 | 65 | |

| Age (yr) | 75.2 ± 7.3 | 75.0 ± 7.5 | 0.9 |

| Gender (M/F) | 46/19 | 44/21 | 0.85 |

| Antiplatelet/anticoagulant drugs (-/+) | 46/19 | 44/21 | 0.85 |

| Hypertension (-/+) | 37/28 | 33/32 | 0.6 |

| Diabetes Mellitus (-/+) | Aug-57 | Dec-53 | 0.47 |

| H. pylori infection (-/+) | 26/39 | 23/42 | 0.72 |

| Location (U/M/L) | 5/33/27 | 10/24/31 | 0.19 |

| Depth (m/sm) | Sep-56 | Jun-59 | 0.58 |

| Ulcer (-/+) | 65/0 | 65/0 | 0 |

| Diameter of the lesion (mm) | 41.9 ± 18.5 | 39.6 ± 12.1 | 0.4 |

| Duration of the operation (min) | 110.6 ± 85.7 | 102.0 ± 54.9 | 0.5 |

| Macroscopic type of the lesion (elevated or flat/combined/depressed) | 42/14/9 | 10/8/1947 | 0.6 |

| Pathological findings (Adenoma/Differentiated ca/Undifferentiated ca) | 26/37/2 | 29/35/1 | 0.76 |

| Lymphatic/venous invasion (-/+) | Jan-64 | Feb-63 | ≥ 0.99 |

| Anastomosis (-/+) | Mar-62 | Mar-62 | ≥ 0.99 |

| Operator type (expert/beginner) | 29/36 | 27/38 | 0.86 |

| Bleeding during ESD (good/poor control) | 51/14 | 49/16 | 0.84 |

| Hemorrhage after ESD (-/+) | Oct-55 | Nov-54 | ≥ 0.99 |

| Clinically significant bleeding (-/+) | Apr-61 | Mar-62 | ≥ 0.99 |

Among the matched samples, the incidence of hemorrhage after ESD was 15.4% (10/65) in the oral EPZ group and 16.9% (11/65) in the injectable OPZ group, with no statistically significant difference seen between the two groups (EPZ group vs OPZ group, OR = 0.89, 95%CI: 0.35-2.27, P ≥ 0.99). The incidence of clinically significant hemorrhage was 6.2% (4/65) in the oral EPZ group and 4.6% (3/65) in the injectable OPZ group, with no significant difference of this parameter between the two groups either (EPZ group vs OPZ group, OR = 1.36, 95%CI: 0.29-6.31, P ≥ 0.99). No significant differences in any of the other variables examined were found between the two groups.

EPZ is the first optical isomer developed as a PPI. Previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of oral EPZ in the treatment of GERD[21,22]. Recently, Bunno et al[23] reported that oral EPZ was effective for ulcer healing after ESD. However, no studies have assessed the efficacy of oral EPZ for the control of hemorrhage after ESD. Recent studies have reported that oral EPZ therapy is a useful alternative to injectable PPI therapy to prevent recurrent hemorrhage in hemorrhagic gastric ulcer patients[24,25]. Laine et al[26], who compared oral and injectable lansoprazole, showed a difference in the intragastric pH only during the first hour after PPI administration, with no difference in the intragastric pH seen between the two groups at ≥ 1.5 h after the drug administration. Javid et al[27] demonstrated an equivalent ability of injectable and high oral doses of various PPIs in suppressing gastric acid secretion, and no significant difference in effect among various PPIs given through different routes on the gastric pH ≥ 6 for 72 h after successful endoscopic hemostasis. Our results were consistent with the findings of these previous studies. Oral EPZ therapy has the advantages of a lower cost and easier administration as compared to injectable PPI therapy, whereas injectable PPIs will still be needed for patients who cannot receive oral medications. Therefore, we conclude that oral EPZ therapy is a useful alternative to intravenous PPI therapy for the prevention of hemorrhage after ESD.

Previous studies have reported the incidence and risk factors for hemorrhage after ESD, although the results are conflicting. We also assessed the risk factors for hemorrhage after ESD, and our analysis identified only the operator experience as a significant predictor of hemorrhage after ESD. Adequate coagulation of the vessels at the ulcer base after ESD is important to prevent delayed hemorrhage. As some experience is required for such coagulation, the incidence of hemorrhage after ESD differs between beginners and experts. A previous study also identified the operator experience as a significant risk factor for hemorrhage after ESD[11]. On the other hand, several studies have reported the absence of any significant effect of the operator experience on the risk of hemorrhage after ESD[6-10,12-14]. These differences in the outcomes were likely caused by the diversity of the ESD procedures and treatments employed. Further investigation is required to clarify the unified risk factors for hemorrhage after ESD.

Our study had some limitations. First of all, injectable EPZ is not available at our hospital; therefore, we compared oral esomeprazole with injectable OPZ. Second, we could not carry out a non-inferiority study, because the number of cases was small. Third, hemorrhage after ESD is usually defined as bleeding, including hematemesis or melena, that necessitates endoscopic treatment and has been reported to occur in 1.3% to 11.9% of patients undergoing ESD[28]. We observed only 10 cases (10/243) with hemorrhage after ESD fulfilling this conventional definition, which made a reasonable comparison between oral EPZ and injectable OPZ difficult. Therefore, in this study, we defined hemorrhage after ESD as described in the text above. This was the reason why the frequency of hemorrhage after ESD was relatively high in this study, while the frequency of clinically significant hemorrhage was comparable to that reported from other studies. Fourth, this study was a 6-year clinical study. During this period, ESD has gradually become more and more popular. Individual learning curves, introduction of new devices, and establishment of education programs over the last few years make reasonable comparisons difficult.

In conclusion, in the present study, we assessed the frequency of hemorrhage after ESD after oral EPZ and injectable OPZ treatments. No difference was seen in the incidence of hemorrhage after ESD between the oral EPZ and injectable OPZ groups. This is the first study to investigate the effectiveness of oral EPZ therapy to prevent hemorrhage after ESD. Further large-scale trials are necessary to clarify the effectiveness of oral EPZ therapy. Oral PPI therapy shows a clear cost benefit and is easier to administer as compared to injectable PPI therapy. Thus, we conclude that oral EPZ therapy is a useful alternative to intravenous PPI therapy for the prevention of hemorrhage after ESD.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is technically difficult and is associated with a high risk of adverse events. Among the adverse events, hemorrhage is a frequently encountered and serious problem. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) have been reported to be effective for controlling hemorrhage after ESD. In this study, the authors compared the efficacy of oral effectiveness of oral esomeprazole (EPZ) therapy with that of injectable injectable omeprazole (OPZ) therapy for the prevention of hemorrhage after ESD.

No comparison of the efficacy of oral PPI therapy vs injectable PPI therapy for the control of hemorrhage after ESD has been carried out previously. Therefore, whether oral PPI therapy or injectable PPI therapy is preferable for the prevention of hemorrhage after ESD remains uncertain. The results of this study contributed to clarifying the efficacy of oral EPZ therapy vs injectable OPZ therapy for the prevention of hemorrhage after ESD.

A quasi-randomized experiment was created using propensity score matching. Among the matched samples, the incidence of hemorrhage after ESD was 15.4% (10/65) in the oral EPZ group and 16.9% (11/65) in the injectable OPZ group. No statistically significant difference was seen between these groups.

This study suggests that oral EPZ therapy is a useful alternative to intravenous PPI therapy for the prevention of hemorrhage after ESD. Oral PPI therapy shows a clear cost benefit and is easier to administer as compared to injectable PPI therapy.

ESD: An endoscopic technique allows en-bloc resection even for large or ulcerated gastric tumors.

The study is very well described and the results are clear. In this study, the authors investigated to compare EPZ vs intravenous omeprazole therapy to prevent hemorrhage after ESD using a quasi-randomized analysis with propensity score matching.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Shu X, Suchanek S, Sugimoto M S- Editor: Kong JX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Ono H, Kondo H, Gotoda T, Shirao K, Yamaguchi H, Saito D, Hosokawa K, Shimoda T, Yoshida S. Endoscopic mucosal resection for treatment of early gastric cancer. Gut. 2001;48:225-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1134] [Cited by in RCA: 1149] [Article Influence: 47.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Gotoda T, Yamamoto H, Soetikno RM. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:929-942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 485] [Cited by in RCA: 507] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Oda I, Saito D, Tada M, Iishi H, Tanabe S, Oyama T, Doi T, Otani Y, Fujisaki J, Ajioka Y. A multicenter retrospective study of endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:262-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 291] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Oka S, Tanaka S, Kaneko I, Mouri R, Hirata M, Kawamura T, Yoshihara M, Chayama K. Advantage of endoscopic submucosal dissection compared with EMR for early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:877-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 487] [Cited by in RCA: 527] [Article Influence: 27.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fujishiro M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric cancer. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2008;11:119-124. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Mannen K, Tsunada S, Hara M, Yamaguchi K, Sakata Y, Fujise T, Noda T, Shimoda R, Sakata H, Ogata S. Risk factors for complications of endoscopic submucosal dissection in gastric tumors: analysis of 478 lesions. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:30-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Takizawa K, Oda I, Gotoda T, Yokoi C, Matsuda T, Saito Y, Saito D, Ono H. Routine coagulation of visible vessels may prevent delayed bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection--an analysis of risk factors. Endoscopy. 2008;40:179-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Okada K, Yamamoto Y, Kasuga A, Omae M, Kubota M, Hirasawa T, Ishiyama A, Chino A, Tsuchida T, Fujisaki J. Risk factors for delayed bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric neoplasm. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:98-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jang JS, Choi SR, Graham DY, Kwon HC, Kim MC, Jeong JS, Won JJ, Han SY, Noh MH, Lee JH. Risk factors for immediate and delayed bleeding associated with endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric neoplastic lesions. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:1370-1376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jeon SW, Jung MK, Cho CM, Tak WY, Kweon YO, Kim SK, Choi YH. Predictors of immediate bleeding during endoscopic submucosal dissection in gastric lesions. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1974-1979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tsuji Y, Ohata K, Ito T, Chiba H, Ohya T, Gunji T, Matsuhashi N. Risk factors for bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric lesions. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2913-2917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Toyokawa T, Inaba T, Omote S, Okamoto A, Miyasaka R, Watanabe K, Izumikawa K, Horii J, Fujita I, Ishikawa S. Risk factors for perforation and delayed bleeding associated with endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric neoplasms: analysis of 1123 lesions. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:907-912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nakamura M, Nishikawa J, Hamabe K, Nishimura J, Satake M, Goto A, Kiyotoki S, Saito M, Fukagawa Y, Shirai Y. Risk factors for delayed bleeding from endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric neoplasms. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:1108-1114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Higashiyama M, Oka S, Tanaka S, Sanomura Y, Imagawa H, Shishido T, Yoshida S, Chayama K. Risk factors for bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric epithelial neoplasm. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:290-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Uedo N, Takeuchi Y, Yamada T, Ishihara R, Ogiyama H, Yamamoto S, Kato M, Tatsumi K, Masuda E, Tamai C. Effect of a proton pump inhibitor or an H2-receptor antagonist on prevention of bleeding from ulcer after endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1610-1616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | McKeage K, Blick SK, Croxtall JD, Lyseng-Williamson KA, Keating GM. Esomeprazole: a review of its use in the management of gastric acid-related diseases in adults. Drugs. 2008;68:1571-1607. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41-55. |

| 18. | Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Reducing bias in observational studies using subclassification on the propensity score. J Am Stat Assoc. 1984;79:516-545. |

| 19. | Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The bias due to incomplete matching. Biometrics. 1985;41:103-116. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Ash AS, Shwartz M. Evaluating the performance of risk-adjustment methods: Dichotomous outcomes. In: Risk Adjustment for Measuring Health Care Outcomes. 2nd edition, edited by Iezzoni LI, Chicago, Health Administration Press 1997; . |

| 21. | Johnson DA, Benjamin SB, Vakil NB, Goldstein JL, Lamet M, Whipple J, Damico D, Hamelin B. Esomeprazole once daily for 6 months is effective therapy for maintaining healed erosive esophagitis and for controlling gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of efficacy and safety. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:27-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Richter JE, Kahrilas PJ, Johanson J, Maton P, Breiter JR, Hwang C, Marino V, Hamelin B, Levine JG; Esomeprazole Study Investigators. Efficacy and safety of esomeprazole compared with omeprazole in GERD patients with erosive esophagitis: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:656-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bunno M, Gouda K, Yamahara K, Kawaguchi M. A Case-Control Study of Esomeprazole Plus Rebamipide vs. Omeprazole Plus Rebamipide on Post-ESD Gastric Ulcers. Jpn Clin Med. 2013;4:7-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sung JJ, Suen BY, Wu JC, Lau JY, Ching JY, Lee VW, Chiu PW, Tsoi KK, Chan FK. Effects of intravenous and oral esomeprazole in the prevention of recurrent bleeding from peptic ulcers after endoscopic therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1005-1010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yen HH, Yang CW, Su WW, Soon MS, Wu SS, Lin HJ. Oral versus intravenous proton pump inhibitors in preventing re-bleeding for patients with peptic ulcer bleeding after successful endoscopic therapy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Laine L, Shah A, Bemanian S. Intragastric pH with oral vs intravenous bolus plus infusion proton-pump inhibitor therapy in patients with bleeding ulcers. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1836-1841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Javid G, Zargar SA, U-Saif R, Khan BA, Yatoo GN, Shah AH, Gulzar GM, Sodhi JS, Khan MA. Comparison of p.o. or i.v. proton pump inhibitors on 72-h intragastric pH in bleeding peptic ulcer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1236-1243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Park CH, Lee SK. Preventing and controlling bleeding in gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. Clin Endosc. 2013;46:456-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |