Published online May 10, 2016. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v8.i9.378

Peer-review started: January 3, 2016

First decision: February 2, 2016

Revised: February 25, 2016

Accepted: March 17, 2016

Article in press: March 18, 2016

Published online: May 10, 2016

Processing time: 125 Days and 5.1 Hours

The best modality for foreign body removal has been the subject of much controversy over the years. We have read with great interest the recent article by Souza Aguiar Municipal Hospital, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, describing their experience with the management of esophageal foreign bodies in children. Non-endoscopic methods of removing foreign bodies (such as a Foley catheter guided or not by fluoroscopy) have been successfully used at this center. These methods could be an attractive option because of the following advantages: Shorter hospitalization time; easy to perform; no need for anesthesia; avoids esophagoscopy; and lower costs. However, the complications of these procedures can be severe and potentially fatal if not performed correctly, such as bronchoaspiration, perforation, and acute airway obstruction. In addition, it has some disadvantages, such as the inability to directly view the esophagus and the inability to always retrieve foreign bodies. Therefore, in Western countries clinical practice usually recommends endoscopic removal of foreign bodies under direct vision and with airway protection whenever possible.

Core tip: The best modality for foreign body removal has been the subject of much controversy over the years. Non-endoscopic methods such as a Foley catheter technique have a lot of advantages, such as their simplicity and cost savings, particularly for proximally located coins. However, their complications can be potentially serious regarding airway obstruction or perforation. This article will discuss the point of view of the European and Western countries, which usually recommend endoscopic removal of foreign bodies under direct vision and with airway protection whenever possible.

- Citation: Burgos A, Rábago L, Triana P. Western view of the management of gastroesophageal foreign bodies. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2016; 8(9): 378-384

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v8/i9/378.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v8.i9.378

We have read with great interest the recent article by Souza Aguiar Municipal Hospital, describing their management of esophageal foreign bodies in children. This is a relevant experience and we understand the authors’ point of view regarding the benefits gained from using non-endoscopic methods for the removal of foreign bodies due to their simplicity and cost savings. However, we would like to point out that the management strategy is different in most of the medical hospitals in Western countries. Generally, it is recommended that endoscopic removal of foreign bodies is carried out under direct vision; in addition, among the child population it is also recommended to protect the airway with an endotracheal tube during foreign body removal. In our opinion, this should be considered as a more effective and safer practice in children.

The aim of this article is to describe a comprehensive approach towards children presenting with foreign body ingestion, and to discuss the difference between endoscopic methods and non-endoscopic methods of removing foreign bodies.

The ingestion of foreign bodies is a frequent complaint in Pediatric Emergency services[1]. Fortunately, only 10%-20% will require removal[2] because most of them (80%) spontaneously advance distally. The primary location of lodged esophageal foreign bodies is the proximal esophagus and coins are the most prevalent foreign bodies. Other esophageal locations include: The aortic arch and the lower esophageal sphincter[1,3]. Only 1% of cases will require a surgical removal[4].

If the foreign body ingestion is suspected (ingestion witnessed by a caretaker, or the child has respiratory or digestive symptoms), we firstly recommend to perform simple chest and abdomen X-ray studies in all children. These X-ray studies sometimes allow us to detect the object (although not all foreign bodies are radiopaque), or complications (such as air in the mediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema, indicating esophageal perforation)[5]. Also, it allows to distinguish between different types of foreign bodies (for instance button batteries can be distinguished from coins because of a double contour from a lateral view)[6]. Although radiographic contrast could be used for foreign bodies which are not radiopaque, it generally should be avoided due to aspiration risk[5]. Computed tomography scan may be performed in selected cases if a complication is suspected. If perforation, peritonitis or small-bowel obstruction are confirmed, endoscopy is contraindicated and, in most cases, surgery is required[5].

The type of object, its location, the child’s symptoms, the skills of the physician, and the usual institutional practice in relation to their available means will dictate the treatment of gastrointestinal foreign bodies.

Many non-endoscopic techniques have been described in the article by Souza Aguiar Municipal Hospital, including Foley catheter balloons.

In experienced hands, particularly for proximally located coins, a Foley catheter under fluoroscopic guidance can be inserted into the esophagus to a depth distal to the site of the impacted object. Then, the balloon is inflated symmetrically and traction is applied until the foreign body is removed. Before the catheter is withdrawn, the child is placed in a prone oblique position with mild cervical extension[6].

Advantages of the Foley catheter method are: Efficacy (83%-90%), quick treatment (20 min), no need for anesthesia, available to be performed on an outpatient basis, and cost-effective with a reported savings of $5027.31 per patient[2,7].

Complications after Foley balloon extraction are rare and generally minor[8-10] but some of them could be potentially serious because the procedure is performed blindly and depends on the physician’s skill. Schunk et al[9] reported a rate of 2% minor and 1% major complications. Minor complications included vomiting and nasal bleeding; major complications are transient airway compromise, mucosal erosion, esophageal mucosal laceration that required extensive surgical repair, respiratory distress and hypoxia[11]. To date, only one case has reportedly led to death, caused by broncoaspiration of a coin during the Foley catheter removal[12].

Careful patient selectionis critical in preventing complications. The use of Foley balloon extraction is contraindicated in the following situations[7,13]: (1) impactions of more than 72 h (or more than 24 h in some centers); (2) three unsuccessful removal attempts; (3) complete obstruction of the esophagus; (4) esophageal perforation; (5) multiple foreign body impaction; (6) signs of airway distress or obstruction; (7) children younger than 1.5 years; (8) sharp-edged foreign bodies; and (9) button batteries that have been impacted for more than 2 h. From our point of view, button batteries should always be removed endoscopically as early as possible because of the likelihood of tissue liquefaction-necrosis and perforation. Foley catheter extraction could only be an acceptable alternative in the first two hours post-impaction if endoscopy is not available[13].

Esophageal bougienage has also been used successfully in different centers[14]. An esophageal dilator is easily and quickly passed down through the esophagus to the estimated depth of the foreign body in order to push it into the stomach. This technique is efficient (success rate of 94%-95% vs 100% endoscopic success rate)[14-16], can be performed quickly without anesthesia in the emergency department, and is available to perform on an outpatient basis. It has been considered to be the most cost-effective strategy in an analysis comparison of 4 management strategies for coins (endoscopy, esophageal bougienage, an outpatient observation period or an inpatient observation period)[17]. Arms et al[15] found a payment difference of $4200 between non-endoscopic and endoscopic techniques.

However, the esophageal bougienage method has some significant additional disadvantages[14]. On one hand, bougienage does not retrieve the foreign body and it may be contraindicated in children with potential intestinal inflammatory or fibrotic conditions, such as Crohn’s disease or a personal history of duodenal or small bowel surgery with intestinal anastomosis due to the risk of gastric or intestinal obstruction requiring further invasive procedures[16]. On the other hand, it is imperative to discard the presence of multiple coins, a battery or a foreign body with a complex configuration because the identification of these foreign bodies requires urgent endoscopic removal[16]. It is unclear whether children under one year of age should be excluded from bougienage, but it may advisable, particularly since most ingestions by infants are also not witnessed. An additional disadvantage is that a second radiography is always needed to determine coin passage into the stomach or the small bowel[16]. Other disadvantages and contraindications are the same as previously pointed out concerning the use of a Foley balloon (see above): No airway protection, lack of direct visualization of the esophagus, patient discomfort and exposure to radiation.

Minor complications of esophageal bougienage are vomiting, discomfort and gagging. To date, there have been no reports of major complications associated with selected bougienage of esophageal coins in children[16] but it is still an uncommon management technique.

A third non-endoscopic uncommon procedure is the penny-pincher technique: A grasping endoscopic forceps is inserted though a soft rubber catheter and is then inserted like an orogastric tube under fluoroscopy. After the forceps reaches the object, the object is grasped and removed. The technique does not require sedation or placement of an advanced airway device[18].

So, in summary, there is still a great grade of controversy regarding non-endoscopic methods, mainly regarding patient safety. Although the complications of these procedures are reported as “low” as shown by the Souza Aguiar Municipal Hospital study, they can be severe and potentially fatal (e.g., airway obstruction, perforation)[9,10], so their performance should be limited to physicians experienced in the procedures and in airway management, with suction apparatus, and oxygen supply readily available[7,15,19]. Therefore, in our opinion, endoscopic approaches are recommended in most cases[1,3,5,6,20,21] when adequate resources are available.

Both, rigid endoscopy and flexible endoscopy procedures are safe and effective for food impaction and foreign bodies[22], allowing excellent visualization and biopsy of the esophagus if required.

Flexible endoscopy is considered as the ‘‘first line’’ approach with a success rate of between 80%-100% and a less than 1% risk of perforation[16,22-24]. Rigid endoscopy is considered as a ‘‘second line’’ when flexible endoscopy is not effective (6.6%) and possibly for those foreign bodies located in the upper esophagus[23]. This technique allows having a wider lumen that is a great help for the removal of foreign bodies[12]. Rigid endoscopy success rate is 87%-98% and perforation rate is 3%.

Compared with the standard practice of endoscopy in adults, it is generally recommended in children that foreign-body removal should be performed under general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation to protect the airway from aspiration[1,20,21,23,25].

Most flexible endoscopy complications are considered minor[26]. Regarding anesthesia, minor complications are described in 1.5% of patients[27] and the most frequent are bronchospasm, delayed extubation and fever[26]. Regarding endoscopy, complications are reported in 2%-3% of patients and decrease with age[28], the most common being hypoxia (1.5%) and bleeding (0.3%). Also, it has been published that a long duration between the ingestion until the endoscopy is performed, and the finding of initial mucosal injury are well-known risk factors related with complications after endoscopic foreign body removal[29].

There are few contraindications to perform an endoscopic procedure in children such as unstable airways, cardiovascular collapse, gastrointestinal perforation or peritonitis. The children’s weight is rarely a contraindication, and upper endoscopic examination can be safely performed in neonates as small as 1.5 to 2 kg[21,30]. Relative contraindications include coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, recent abdominal surgery, unstable cardiopulmonary disease, and recent oral intake[21,26].

Endoscopic treatment has a lot of advantages. As already mentioned, the greatest advantage is the capability of direct evaluation of esophageal mucosa because esophageal abnormalities in children range between 6% and 13% in different foreign bodies studies[22,23]. Endoscopic examination allows biopsy if required (e.g., eosinophilic esophagitis), and also allows more complex techniques such as stricture-dilation, as well as the possibility to perform a push enteroscopy in selected cases. It can be used not only for proximally located coins, but also for different types and multiple objects in any location (upper, medium or lower esophagus and also stomach or duodenum), as will be described later.

In addition, various retrieval devices can be used to remove the object (polypectomy snares, rat-tooth and alligator forceps, Dormier baskets, magnetic probes polyp graspers, retrieval nets, and friction-fit adaptors or banding caps)[6]. The most appropriate device according to the characteristics of the foreign body should be chosen. However, the type of the device can be changed depending on the success with the previous one.

We agree with the authors regarding Magill forceps. Magill forceps are angled forceps commonly used in anesthesia. They can remove some objects located in the oropharynx or upper esophagus, with the help of a laryngoscope or rigid esophagoscopy under general anesthesia[31,32]. A 96% success rate is described with this method[33].

An overtube may be used to provide airway protection in adults. In children its use has not been generally recommended due to its diameter, except in selected cases[34]. A protector hood or a transparent distal cap[6,20] can also help to avoid mucosal injury during endoscopic removal procedure of sharp objects.

The risk and the timing of the endoscopic intervention depend on: The shape, size and content of the foreign body, anatomic location, and the time since their ingestion. Classifications of foreign bodies and timing of the endoscopic intervention are described in Tables 1 and 2. In the case of esophageal obstruction, button cell batteries, magnets or sharp-pointed objects in the esophagus, emergent removal is always required.

| Objects shape |

| Short-blunt: Coins, rings |

| Long: Utensils for eating, string, cord, toothbrush |

| Sharp-pointed: Nails, pins, tacks, toothpicks, chicken, fish bones |

| Objects including poisons |

| Button cell and disk batteries |

| Cylindrical batteries (these batteries do not typically discharge electrical current the way button batteries do) |

| Narcotic packets |

| Objects inducing esophageal or gastrointestinal obstruction |

| Magnets |

| Food bolus impaction |

| Superabsorbent polymers |

| Emergent endoscopy |

| Esophageal obstruction (patient unable to manage secretions) |

| Sharp-pointed objects in the esophagus (or in the stomach/small bowel if symptomatic) |

| Disk or button cell batteries in the esophagus (or in the stomach/small bowel if symptomatic) |

| Magnets in the esophagus (or in the stomach/small bowel if symptomatic) |

| Urgent endoscopy |

| Esophageal foreign objects that are not sharp-pointed |

| Esophageal food impaction in patients without complete obstruction |

| Sharp-pointed objects in the stomach or duodenum (if asymptomatic) |

| Objects > 6 cm in length at or above the proximal duodenum in adults |

| Disk and button cell batteries in the stomach (if age < 5 and button battery > 20 mm) |

| Magnets within endoscopic reach (if asymptomatic) |

| Absorptive object |

| Nonurgent (elective) endoscopy |

| Objects in the stomach with diameter 2.5 cm in adults |

| Objects > 2 cm and longer than 5 cm in older children |

| Objects longer than 3 cm in infants and young children |

| Coins in the esophagus may be observed for 12-24 h before endoscopic removal in an asymptomatic patient |

| Disk and button cell batteries and cylindrical batteries that are in the stomach of patients without signs of gastrointestinal injury may be observed for as long as 48 h. Batteries remaining in the stomach longer than 48 h should be removed |

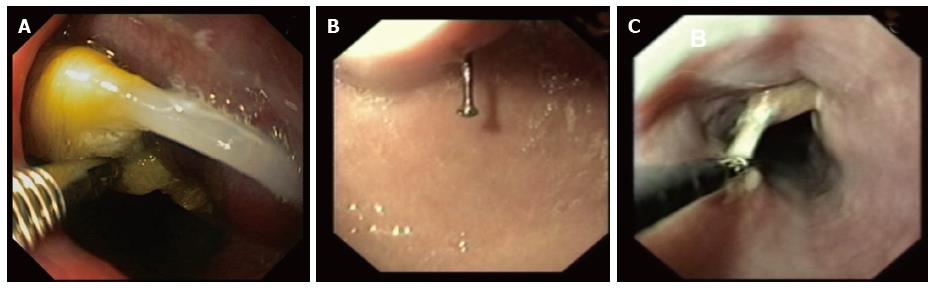

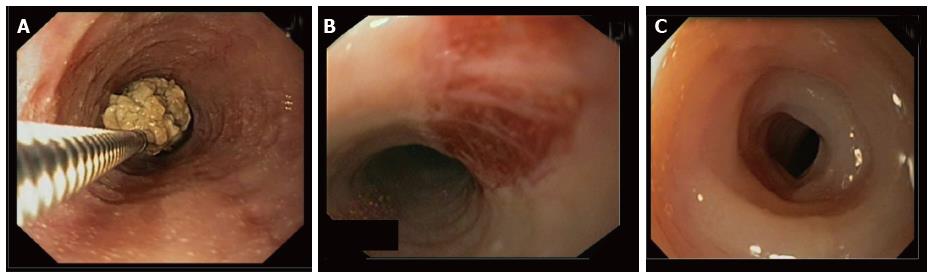

Regarding object shape, short-blunt objects (coins) are the most prevalent foreign bodies in children. If the patient is asymptomatic, coins placed especially in the distal esophagus can be observed for 12 to 24 h (Figure 1). Endoscopy is indicated if the coins remain in the esophagus or if the patient is symptomatic. Endoscopic devices that are most frequently used in this situation are snare, rat-tooth or alligator forceps or retrieval nets[6].

Long objects can be removed with a snare or basket and, in selected cases in the adult population, with the help of an overtube.

Sharp-pointed objects have risk of perforation (35%) and they must always be removed (Figure 2). We can use forceps, snares or retrieval nets. If the object cannot be reached endoscopically due to deep migration, daily radiographs should be obtained[6,20].

Regarding object location, 20% of foreign bodies lodged in the esophagus may harbor risk of aspiration and perforation, so we recommend endoscopic removal in the first 24 h of ingestion. The size will be determinant for its removal if the foreign body has already passed to the stomach (60%). In older children, objects wider than 2 cm and longer than 4-6 cm should be removed[5,35-37]. In infants and young children, the limit could be 3 cm[3]. If the object has passed the duodenum, conservative treatment is recommended (Table 2).

In relation with the type of foreign body, button cell and disk batteries are very dangerous because of the likelihood of liquefaction necrosis of the tissues and perforation. Therefore, endoscopic emergent removal is always recommended and it can be completed with a rat tooth grasper, a retrieval basket or a net[20]. In this situation, we can also use a through-the-scope (TTS) balloon (Fogarty balloon or Controlled Radial Expansion balloon) to remove the foreign body. This is a similar practice as the authors recommend with the Foley catheter in the article, but with the additional help and safety provided by both, the endoscope and the balloon together, with the importance of adding the airway protection[6]. Cylindrical batteries lodged in the stomach of an asymptomatic patient may be observed for 48 h; however, batteries that do not pass spontaneously, batteries in a symptomatic patient or multiple gastric cylindrical batteries should be removed[6,35].

Magnets should also always be removed, even if only one magnet is evident[6]. If the child ingests two magnets or a magnet and a metal object, these two objects can trap a portion of bowel wall causing necrosis, fistula or perforation.

Food bolus impaction in children can often mean an underlying esophageal pathology (e.g., eosinophilic esophagitis)[38]. Sometimes intravenous Glucagon is firstly used but its results are equivocal[39]. Bolus can be “extracted” or “pushed” into the stomach with a snare or retrieval net (Figure 3).

Other completely different types of foreign bodies are narcotic packets: Unfortunately, children can transport these substances into their stomach like “body packing”. In this case, endoscopic removal is contraindicated in order to avoid the rupture of the contents[6,20].

Finally, superabsorbent polymers in some feminine hygiene products (tampons) and children’s toys can absorb and retain large amounts of water causing intestinal obstruction if they are ingested[40]. In the case of ingestion of superabsorbent objects, emergent or urgent endoscopy should be recommended with a retrieval net or basket for round objects and a polyp snare for larger and irregular shaped objects.

The best modality for foreign body removal has been the subject of much controversy over the years. Non-endoscopic methods such as a Foley catheter or an esophageal bougienage have many advantages, such as their simplicity and cost savings, particularly for proximally located coins. However, their complications can be potentially serious regarding airway obstruction or perforation. Only experienced hands should perform both techniques and they should be avoided if there has been previous esophageal surgery or the object has been impacted for more than 24 h. Endoscopic procedures allow direct examination of the esophagus and more complex techniques with airway control; in addition, they can be used not only for proximally coins, but also for different types and multiple objects in any location (esophagus, stomach or duodenum). Therefore, in Western countries clinical practice usually recommends endoscopic removal of foreign bodies under direct vision and with airway protection whenever possible.

P- Reviewer: Chen JQ, Lee CL, Mentes O, Xiao Q S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Rahman I, Patel P, Boger P, Rasheed S, Thomson M, Afzal NA. Therapeutic upper gastrointestinal tract endoscopy in Paediatric Gastroenterology. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:169-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Little DC, Shah SR, St Peter SD, Calkins CM, Morrow SE, Murphy JP, Sharp RJ, Andrews WS, Holcomb GW, Ostlie DJ. Esophageal foreign bodies in the pediatric population: our first 500 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:914-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Spanish Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. Spanish Association of Pediatrics (SEGHNP-AEP). Ingestion of foreign bodies. Diagnostic-therapeutic protocols of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Pediatric Nutrition. 2nd ed. Spain: Editorial Ergón 2010; 131-134. |

| 4. | Kay M, Wyllie R. Pediatric foreign bodies and their management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2005;7:212-218. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Ikenberry SO, Jue TL, Anderson MA, Appalaneni V, Banerjee S, Ben-Menachem T, Decker GA, Fanelli RD, Fisher LR, Fukami N. Management of ingested foreign bodies and food impactions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:1085-1091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 468] [Cited by in RCA: 501] [Article Influence: 35.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Louie MC, Bradin S. Foreign body ingestion and aspiration. Pediatr Rev. 2009;30:295-301, quiz 301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Abdurehim Y, Yasin Y, Yaming Q, Hua Z. Value and efficacy of foley catheter removal of blunt pediatric esophageal foreign bodies. ISRN Otolaryngol. 2014;2014:679378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Campbell JB, Condon VR. Catheter removal of blunt esophageal foreign bodies in children. Survey of the Society for Pediatric Radiology. Pediatr Radiol. 1989;19:361-365. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Schunk JE, Harrison AM, Corneli HM, Nixon GW. Fluoroscopic foley catheter removal of esophageal foreign bodies in children: experience with 415 episodes. Pediatrics. 1994;94:709-714. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Wang J, Wang P. Clinical analysis on 138 cases of removing esophageal foreign bodies in children by utilizing foley catheter. CJEBM. 2010;10:1118-1119. |

| 11. | McGuirt WF. Use of Foley catheter for removal of esophageal foreign bodies. A survey. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1982;91:599-601. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Hawkins DB. Removal of blunt foreign bodies from the esophagus. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1990;99:935-940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gasior AC, Knott EM, Sharp SW, Snyder CL, St Peter SD. Predictive factors for successful balloon catheter extraction of esophageal foreign bodies. Pediatr Surg Int. 2013;29:791-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Allie EH, Blackshaw AM, Losek JD, Tuuri RE. Clinical effectiveness of bougienage for esophageal coins in a pediatric ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:1263-1269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Arms JL, Mackenberg-Mohn MD, Bowen MV, Chamberlain MC, Skrypek TM, Madhok M, Jimenez-Vega JM, Bonadio WA. Safety and efficacy of a protocol using bougienage or endoscopy for the management of coins acutely lodged in the esophagus: a large case series. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:367-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Heinzerling NP, Christensen MA, Swedler R, Cassidy LD, Calkins CM, Sato TT. Safe and effective management of esophageal coins in children with bougienage. Surgery. 2015;158:1065-1070; discussion 1071-1072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Soprano JV, Mandl KD. Four strategies for the management of esophageal coins in children. Pediatrics. 2000;105:e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gauderer MW, DeCou JM, Abrams RS, Thomason MA. The ‘penny pincher’: a new technique for fast and safe removal of esophageal coins. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:276-278. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Dahshan AH, Kevin Donovan G. Bougienage versus endoscopy for esophageal coin removal in children. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:454-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kramer RE, Lerner DG, Lin T, Manfredi M, Shah M, Stephen TC, Gibbons TE, Pall H, Sahn B, McOmber M. Management of ingested foreign bodies in children: a clinical report of the NASPGHAN Endoscopy Committee. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;60:562-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 35.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lightdale JR, Acosta R, Shergill AK, Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi K, Early D, Evans JA, Fanelli RD, Fisher DA, Fonkalsrud L. Modifications in endoscopic practice for pediatric patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:699-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Russell R, Lucas A, Johnson J, Yannam G, Griffin R, Beierle E, Anderson S, Chen M, Harmon C. Extraction of esophageal foreign bodies in children: rigid versus flexible endoscopy. Pediatr Surg Int. 2014;30:417-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gmeiner D, von Rahden BH, Meco C, Hutter J, Oberascher G, Stein HJ. Flexible versus rigid endoscopy for treatment of foreign body impaction in the esophagus. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:2026-2029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Popel J, El-Hakim H, El-Matary W. Esophageal foreign body extraction in children: flexible versus rigid endoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:919-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Katsinelos P, Kountouras J, Paroutoglou G, Zavos C, Mimidis K, Chatzimavroudis G. Endoscopic techniques and management of foreign body ingestion and food bolus impaction in the upper gastrointestinal tract: a retrospective analysis of 139 cases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:784-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Temiz A. Efficiency of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in pediatric surgical practice. World J Clin Pediatr. 2015;4:113-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lee WS, Zainuddin H, Boey CC, Chai PF. Appropriateness, endoscopic findings and contributive yield of pediatric gastrointestinal endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:9077-9083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Thakkar K, El-Serag HB, Mattek N, Gilger MA. Complications of pediatric EGD: a 4-year experience in PEDS-CORI. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:213-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Park YK, Kim KO, Yang JH, Lee SH, Jang BI. Factors associated with development of complications after endoscopic foreign body removal. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:230-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Volonaki E, Sebire NJ, Borrelli O, Lindley KJ, Elawad M, Thapar N, Shah N. Gastrointestinal endoscopy and mucosal biopsy in the first year of life: indications and outcome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:62-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Crysdale WS, Sendi KS, Yoo J. Esophageal foreign bodies in children. 15-year review of 484 cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1991;100:320-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kessler E, Chappell JS. Upper gastro-intestinal endoscopy in chidren. S Afr Med J. 1979;56:591-593. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Cetinkursun S, Sayan A, Demirbag S, Surer I, Ozdemir T, Arikan A. Safe removal of upper esophageal coins by using Magill forceps: two centers’ experience. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2006;45:71-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Barth BA, Banerjee S, Bhat YM, Desilets DJ, Gottlieb KT, Maple JT, Pfau PR, Pleskow DK, Siddiqui UD, Tokar JL. Equipment for pediatric endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:8-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Sahn B, Mamula P, Ford CA. Review of foreign body ingestion and esophageal food impaction management in adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55:260-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Smith MT, Wong RK. Foreign bodies. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2007;17:361-382, vii. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Paul RI, Jaffe DM. Sharp object ingestions in children: illustrative cases and literature review. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1988;4:245-248. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Lao J, Bostwick HE, Berezin S, Halata MS, Newman LJ, Medow MS. Esophageal food impaction in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2003;19:402-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Weant KA, Weant MP. Safety and efficacy of glucagon for the relief of acute esophageal food impaction. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012;69:573-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Mirza B, Sheikh A. Mortality in a case of crystal gel ball ingestion: an alert for parents. APSP J Case Rep. 2012;3:6. [PubMed] |