Published online Apr 25, 2016. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v8.i8.374

Peer-review started: November 12, 2015

First decision: December 7, 2015

Revised: January 16, 2016

Accepted: February 14, 2016

Article in press: February 16, 2016

Published online: April 25, 2016

Processing time: 156 Days and 2.2 Hours

A 48-year-old man underwent laparoscopic sigmoid colon resection for cancer and surveillance colonoscopy was performed annually thereafter. Five years after the resection, a submucosal mass was found at the anastomotic staple line, 15 cm from the anal verge. Computed tomography scan and endoscopic ultrasound were not consistent with tumor recurrence. Endoscopic mucosa biopsy was performed to obtain a definitive diagnosis. Mucosal incision over the lesion with the cutting needle knife technique revealed a creamy white material, which was completely removed. Histologic examination showed fibrotic tissue without caseous necrosis or tumor cells. No bacteria, including mycobacterium, were found on culture. The patient remains free of recurrence at five years since the resection. Endoscopic biopsy with a cutting mucosal incision is an important technique for evaluation of submucosal lesions after rectal resection.

Core tip: This case report demonstrates the importance of endoscopic biopsy using a cutting mucosal incision as a diagnostic tool for a submucosal mass that develops next to the staple line after sigmoid colon resection with a double-stapled anastomosis. We feel that these findings will be of special interest to the readers.

- Citation: Morimoto M, Koinuma K, Lefor AK, Horie H, Ito H, Sata N, Hayashi Y, Sunada K, Yamamoto H. Diagnosis of a submucosal mass at the staple line after sigmoid colon cancer resection by endoscopic cutting-mucosa biopsy. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2016; 8(8): 374-377

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v8/i8/374.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v8.i8.374

Submucosal tumors, such as neuroendocrine tumors (NET) or gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST), are occasionally encountered in the rectum, and are categorized based on the tissue of origin as muscular or neural derived. The differential diagnosis of a submucosal mass adjacent to the staple line after colon resection is extensive, and includes NET, GIST, and tumor recurrence. We report a patient with a submucosal mass at the site of a stapled anastomosis that developed five years after initial resection of a tumor.

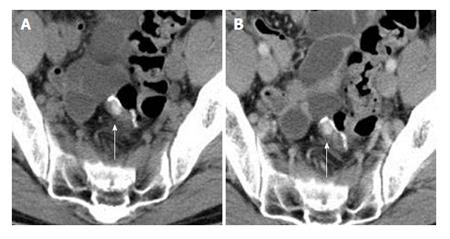

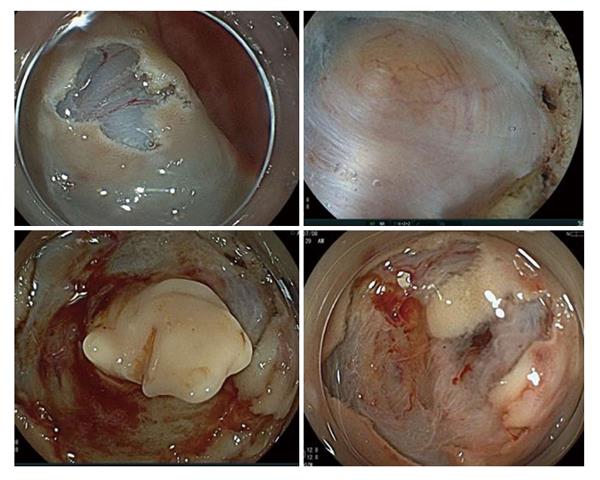

A 48-year-old male was referred for treatment of sigmoid colon cancer six years previously. He had a past medical history of allergic dermatitis at 26 years of age. Laboratory data showed that both serum levels of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) were within the normal limits. Enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan showed a sigmoid colon cancer with no evidence of distant metastases. Laparoscopic sigmoid colon resection with a double stapled anastomosis was performed. Macroscopic pathology showed 0-Ip tumor 30 mm in diameter. Microscopic pathology showing a well-differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma invading the muscularis propria with no regional lymph node metastases (UICC category; T2 N0 M0), classified as pathologic stage I disease. The patient remained asymptomatic with no signs of recurrence for four years. Five years postoperatively, a submucosal mass measuring 10 mm in size was detected at the staple line located 15 cm from the anal verge during an annual surveillance colonoscopy (Figure 1). Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) showed a well-demarcated and circumscribed homogeneous high echoic lesion in the submucosal layer (Figure 2). The surface of the lesion was covered with normal-appearing mucosa. The submucosal tumor showed no deformity with application of air pressure during the colonoscopy and was negative for the “cushion sign”. Abdominal CT scan revealed a small, high-density well-demarcated mass without contrast-enhancement in the colonic wall (Figure 3). No metastatic lesions were seen on CT scan. In retrospect, the small high intensity area near the anastomosis had been evident on a CT scan performed four years after resection, and was gradually increasing in size. Tumor markers, including CEA and CA 19-9, remained within normal limits. It was felt unlikely that the mass was malignant based on its appearance and behavior. However, the mass showed slow growth and there was no definitive diagnosis. Routine endoscopic biopsy was thought to be difficult to establish a diagnosis because most of the target lesion was located in the submucosal layer. Endoscopic cutting mucosal biopsy of the lesion was planned. A precutting needle knife (KD-10Q-1, Olympus Corp, Tokyo, Japan) and an electrosurgical generator (VIO 300D; ERBE Elektromedizin Ltd, Tübingen, Germany) in endocut mode (effect, 1; duration, 4; interval, 1) were used. A mucosal incision was made over the lesion with the cutting needle knife technique after submucosal injection of saline containing 0.001% epinephrine and 0.004% indigocarmine. A pale, orange nodule covered by fibrotic material was seen in the submucosal tissue stained with the blue dye of the indigocarmine, compatible with the EUS results. The nodule was easily distinguished from the muscularis propria by its color because the muscularis propria is white. The fibrotic tissue above the lesion was incised using biopsy forceps (Radial Jaw™ 4, Boston Scientific Corp, Marlborough, MA), revealing a creamy white material, which was completely removed using the forceps. The wall of the remaining cavity was not resected. The specimen was gray-white and soft (Figure 4). The creamy appearance of the material led to the consideration of caseous necrosis associated with tuberculosis. However, pathological examination showed fibrotic tissues with necrotic material and no signs of caseous necrosis associated with tuberculosis, Crohn’s disease or malignancy. The patient remains free of recurrence, five years after the initial resection.

The differential diagnosis of submucosal tumors of the colon and rectum includes GIST, NET, inflammatory polyps, desmoid-type fibromatosis, and local recurrence[1]. Submucosal masses due to intestinal tuberculosis are rare[2]. In this patient, a submucosal mass was located next to the anastomotic staple line, with both CT scan and EUS showing no typical signs of GIST, NET or local recurrence. Local recurrence is rare in patients with T1-2 colorectal cancers[3]. However, we could not rule out the possibility of tumor recurrence because the lesion showed slow growth on annual CT scans. Thus, an endoscopic biopsy is a reasonable method to obtain a tissue diagnosis. Endoscopic mucosal cutting biopsy is a safe and effective method to establish the diagnosis of submucosal masses[4]. This technique can be used in institutions where endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is routinely performed for T1 colorectal cancers[5]. ESD of superficial colorectal neoplasms has become well-accepted over the past decade, with a low complication rate (delayed bleeding 2%, perforation 1.3%, emergency surgical operation 0.2%)[6,7]. In this patient, endoscopic biopsy with mucosal incision avoided the need for a second surgical resection.

The double stapling technique for colorectal anastomoses is commonly used after sigmoid colon resection. Surgical procedures that include partial or total transection of the digestive tract evoke considerable physiological morphological, functional, and metabolic changes in adjacent intestinal tissue[8]. The inflamed area of a fibrotic scar decreases after postoperative day seven with a minimal amount of fibrosis by postoperative day 90[9]. Luijendijk et al[10] reported that suture granulomas were seen in 25% of patients with a past history of abdominal surgery. Inflammatory and foreign body reactions to such material can produce lesions mimicking cancer, clinically and radiologically[11]. There are reports of patients who underwent repeat surgical resection to rule out tumor recurrence[10,12]. It is unknown whether the fibrotic lesion was associated with the anastomotic stapler and adjacent tissue inflammation in the present patient. The persistent production of cytokines by inflammatory stimulation associated with the fibrotic process may lead to submucosal fibrosis.

Endoscopic biopsy using a cutting mucosal incision is a useful diagnostic tool for submucosal masses that develop next to a staple line after rectal resection and anastomosis using the double stapling technique.

Submucosal tumor.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST), neuroendocrine tumors (NEC), local recurrence.

All tumor markers were within normal limits.

A malignant tumor was not expected based on computed tomography and endoscopic ultrasonography results.

Tissue fibrosis.

Endoscopic repeat biopsy.

References 10 and 12.

There is a possibility of developing a granulomatous mass (fibrotic tissue) at the staple line in future patients. This lesion mimics a submucosal tumor such as a GIST or NEC. Some surgeons may initially plan a second resection, similar to another low anterior resection. This case report reminds surgeons of the possibility of a benign lesion.

This is an interesting case report.

P- Reviewer: Battal B, Friedland S S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs): definition, occurrence, pathology, differential diagnosis and molecular genetics. Pol J Pathol. 2003;54:3-24. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Yanagida T, Oya M, Iwase N, Okuyama T, Terada H, Sasaki K, Akao S, Ishikawa H, Satoh H. Rectal submucosal tumor-like lesion originating from intestinal tuberculosis. J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:822-825. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Lee W, Lee D, Choi S, Chun H. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery and radical surgery for T1 and T2 rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1283-1287. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Kataoka M, Kawai T, Yagi K, Sugimoto H, Yamamoto K, Hayama Y, Nonaka M, Aoki T, Fukuzawa M, Fukuzawa M. Mucosal cutting biopsy technique for histological diagnosis of suspected gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach. Dig Endosc. 2013;25:274-280. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Tanaka S, Kashida H, Saito Y, Yahagi N, Yamano H, Saito S, Hisabe T, Yao T, Watanabe M, Yoshida M. JGES guidelines for colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection/endoscopic mucosal resection. Dig Endosc. 2015;27:417-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 436] [Article Influence: 43.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nakajima T, Saito Y, Tanaka S, Iishi H, Kudo SE, Ikematsu H, Igarashi M, Saitoh Y, Inoue Y, Kobayashi K. Current status of endoscopic resection strategy for large, early colorectal neoplasia in Japan. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:3262-3270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yamamoto H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection--current success and future directions. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9:519-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nandakumar G, Stein SL, Michelassi F. Anastomoses of the lower gastrointestinal tract. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:709-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Berho M, Wexner SD, Botero-Anug AM, Pelled D, Fleshman JW. Histopathologic advantages of compression ring anastomosis healing as compared with stapled anastomosis in a porcine model: a blinded comparative study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:506-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Luijendijk RW, de Lange DC, Wauters CC, Hop WC, Duron JJ, Pailler JL, Camprodon BR, Holmdahl L, van Geldorp HJ, Jeekel J. Foreign material in postoperative adhesions. Ann Surg. 1996;223:242-248. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Tripathi PB, Kini S, Amarapurkar AD. Foreign body giant cell reaction mimicking recurrence of colon cancer. Trop Gastroenterol. 2009;30:219-220. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Dickinson J. Foreign body granuloma following anastomosis with the anastomotic stapler. J Pediatr Surg. 1971;6:489. [PubMed] |