Published online Feb 10, 2016. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v8.i3.192

Peer-review started: May 11, 2015

First decision: July 25, 2015

Revised: August 20, 2015

Accepted: October 12, 2015

Article in press: October 13, 2015

Published online: February 10, 2016

Processing time: 268 Days and 12.4 Hours

Here we offer a review of the literature regarding endoscopic ultrasound-guided ethanol ablation for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours and describe the case of a cystic tumour completely ablated after a multisession procedure. A total of 35 PubMed indexed cases of treated functioning and non-functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours resulted from our search, 29 of which are well-documented and summarised. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided ethanol ablation appears as a local, minimally invasive treatment of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours, suitable for selected patients. This technique appears feasible, relatively safe and efficient, especially when applied to symptom relief in functioning tumours, aiming at loss of endocrine secretion. For non-functioning tumours, where the goal is complete tissue ablation, eus guided ethanol ablation can provide good results for patients who are unfit for surgery or for those who refuse surgical resection. Its role in “fit for surgery” patients requires assessment through further studies.

Core tip: We report a complete review of the literature about endoscopic ultrasound-guided ethanol ablation for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. The case of a cystic tumour completely ablated after a multisession procedure is described. On long term follow-up a durable remission of the tumour was obtained; a complete image gallery showing the pre and post-treatment appearance is available. The technical aspects, clinical success and complication rates related to this kind of procedures are described.

- Citation: Armellini E, Crinò SF, Ballarè M, Pallio S, Occhipinti P. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided ethanol ablation of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours: A case study and literature review. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2016; 8(3): 192-197

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v8/i3/192.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v8.i3.192

In recent years the improvement of diagnostic and therapeutic technologies has led to less invasive treatments in any field of medicine with a shift from surgery to imaging guided treatments.

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) has demonstrated excellent diagnostic accuracy for bilio-pancreatic district diseases and high safety and precision when applied for operative purposes. Along the years this peculiarity has made of EUS an optimal technique for imaging and cytological diagnosis, as well as for execution of more advanced procedures (i.e., drainages and local treatments).

The current management of T1 and T2 pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (pNETs ) is somewhat similar to that of most pancreatic tumours (surgical resection), with a considerable economic burden and post-operative complications. However we are dealing with a pathology that offers a better prognosis and that is potentially responsive to local treatments[1,2].

Neuroendocrine tumours arise from cells present in the diffuse endocrine system and can be found throughout the body. They are most commonly located in the gastrointestinal tract and lung but are also found in the pancreas[3]. The 2010 World Health Organization (WHO) classification divides the pNETs in three grades (G1, G2 and G3) on the basis of Ki-67 nuclear antigen expression (< 2%; 2%-20% and > 20%) and mitotic rate (< 2; 2-20 and > 20). Biopsy is most commonly used to assess the grade of the tumour. According to the TNM, the tumour is classified as T1a (< 1 cm), T1b (1-2 cm) and T2 (larger than 2 cm); T3 and T4 are locally advanced tumours (Table 1).

| Grade | Ki-67 index (%) | Mitotic count/10 HPF |

| G1 | ≤ 2 | < 2 |

| G2 | 3-20 | 2-20 |

| G3 | > 20 | > 20 |

| TNM | Size (cm) | Muscularis propria invasion |

| T1a | < 1 | _ |

| T1b | 1-2 | _ |

| T2 | > 2 | + |

Tumour grading and tumour stage are the main prognostic factors of pNETs. Well and moderately differentiated have a significantly better survival compared to poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas.

pNETs are also classified as functioning and non-functioning depending on the secretion of specific hormones. Functioning tumours are commonly associated with a specific hormonal syndrome directly related to a hormone secreted by the neoplasm such as insulinomas with ipoglicemia, gastrinomas with Zollinger–Ellison or carcinoid syndrome. Most non-functioning tumours occur in the head of the pancreas and produce mass effect symptoms. When small, they are usually incidentally discovered due to the incremental use of high-level diagnostic imaging.

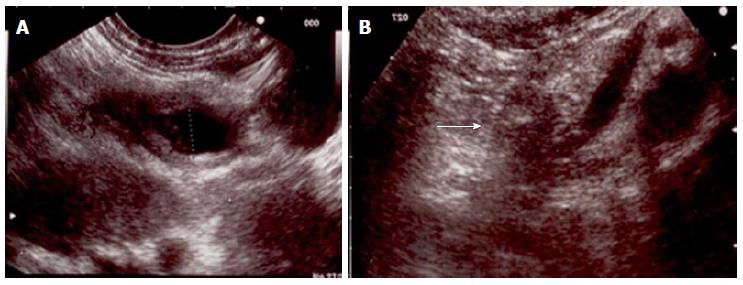

EUS is the optimal diagnostic modality and can provide a biopsy specimen for histological confirmation and differentiation grade. The EUS image is usually of a solid, ipoechoic, round and smooth nodule, sometimes with a cystic central component (bull’s eye appearance).

To date, the management of pancreatic sporadic, small (< 2 cm), asymptomatic, low-grade (G1) NETs suggests a “wait and see” strategy. Surgical resection of non-functioning pNETs is actually recommended for large (> 2 cm) or G2-G3 lesions[4]. For patients unfit for surgery due to high-risk comorbidity or for those who refuse resection, the EUS-guided ethanol ablation has been reported in a few cases[5] as a local and minimally invasive therapy.

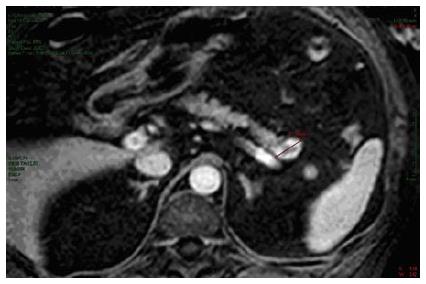

A 58-year-old man with essential hypertension and recent onset of glucose intolerance was referred for a transabdominal ultrasonography (US). Other laboratory test results including levels of carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen were all within normal ranges. The US session diagnosed a focal lesion on the pancreatic tail. An abdominal magnetic resonance image showed a 22 mm nodule with peripheral hypervascularization (Figure 1), and EUS confirmed a “bull’s-eye” appearance nodule with peripheral hypervascular pattern via power Doppler and a central cystic component. The EUS-guided FNA of the lesion confirmed the diagnosis of pNET. The Ki67 proliferative index was > 5% to yield a G2 grade. However, because the patient adamantly refused surgical resection, we decided to ablate the lesion via EUS-guided ethanol injection.

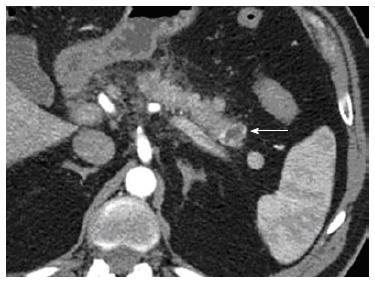

After aspiration of the cystic component, a mean volume of 1.7 mL of 95% ethanol per session was injected into the tumour and re-aspirated using a 25-gauge needle (Echo-tip ultra, Cook, Limerick, Ireland) through a linear array echoendoscope (Figure 2). Three treatment sessions over six months were performed to ablate the nodule (Figure 3).

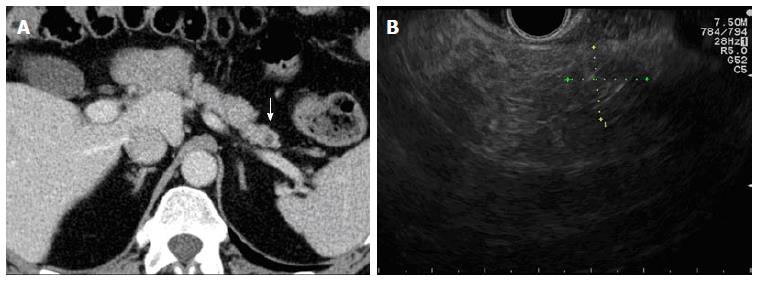

The hospitalization time was 2 d for each session. The patient experienced mild pancreatitis in 2 out of 3 sessions - that resolved with standard-of-care. No major or late complications were observed. After 24 mo, we achieved a durable and complete remission of the tumour as shown by CT and EUS morphological imaging (Figure 4).

Most diagnosed pNETs are non-functioning tumours (90.8%); the remaining 9% are malignant functioning tumours such as gastrinomas (4.2%), insulinomas (2.5%), glucagonomas (1.6%), and VIPomas (0.9%). Although commonly perceived to be indolent tumours, they exhibit a broad range of growth rates, malignant potential, and overall prognosis. Most patients with pNETs (60%-70%) present with metastatic disease at diagnosis. Following surgical resection, the 5-year cumulative survival for pNETs other than insulinomas is roughly 65% with a 10-year survival of 45%[6].

Patients with incidental diagnosis of pNETs with a tumour size < 2 cm and low-grade (G1) dysplasia have a 5-year overall survival of 100% with a minimal risk of recurrence[6]. In this setting, a “wait and see” policy is recommended.

On the contrary, surgical resection is the standard treatment for functioning and non-functioning G2-G3 pNETs. However, this is associated with a high risk of complications. Even when performed in high-volume centres, typical pancreatic resections (pancreaticoduodenectomy or distal pancreatectomy) have a mortality rate of about 5% with complications ranging from 40% to 50%[7]. This is particularly common in the elderly or patients with comorbidities. Typical pancreatic resections are also associated with a high incidence of exocrine and endocrine insufficiency.

In an attempt to reduce complications and pancreatic impairment, new parenchyma-sparing resection techniques such as enucleation and middle pancreatectomy (resection of the central part of the gland) have been applied to small tumours[8]. Although pancreatic head tumour enucleation resulted in decreased operative time and length of hospitalization, the 5-year survival and overall morbidity and mortality were comparable to standard surgical resection even for small pNETs[9]. To date, no alternative treatment has been standardized for patients unfit for surgery or for those who refuse resection.

In the recent decades, EUS has evolved into a useful therapeutic tool for treating a broad range of tumours. EUS-guided injection has been applied both as a pancreatic cancer treatment aimed at controlling pain through nerve blockade as well as a solid tumour therapy for the introduction of brachytherapy seeds and viral vectors or as a tool for ablation therapy[10,11]. The pNET EUS-guided ethanol ablation is a new, less invasive therapeutic option although it remains rare.

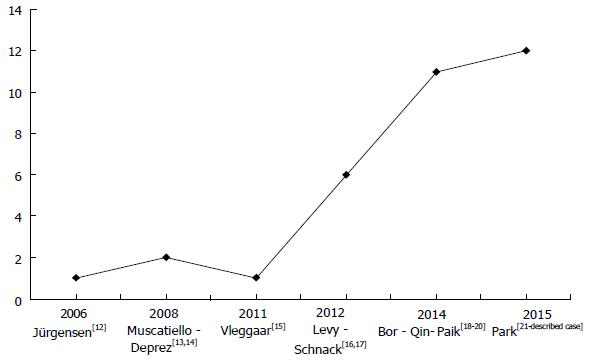

A PubMed literature review showed 26 patients affected by small pNETs (maximum diameter of 21 mm) who underwent EUS-guided ethanol ablation[12-21] including 19 functioning and 10 non-functioning tumours (Table 2). The number of patients treated by this tecnique progressively increased from 2006 to 2015 (Figure 5).

| No. of patients1 | 27 |

| Age, yr | |

| Mean (range) | 59 (27-89) |

| Sex, male/female | 10-17 |

| No. of tumors | 30 |

| Functioning | 19 |

| Non functioning | 11 |

| Type of functioning tumor | |

| Insulinoma | 18 |

| Vipoma | 1 |

| Diameter, mm | |

| Mean (range) | 12.5 (5-22) |

Conscious sedation is generally reported during the procedure. A mean hospitalization time of 2 d/session is usually necessary even in the absence of complications.

Technical success is reported in 100% of cases; a 22 or 25 gauge needle was generally used to inject a small volume of ethanol with a range between 0.2 and 8 mL per session. The choice of ethanol volume is a function of tumour size. For small (≤ 20 mm) tumours, Qin et al[19] suggested that the volume be calculated as follows. For round tumours, the volume of ethanol corresponds to half the tumour size; for oval or irregular tumours, the volume of ethanol is (major axis + minor axis of the tumour)/2. A 1.0 mL syringe should be used for precise injection.

In terms of therapeutic outcomes, differentiation of functioning and non-functioning tumours seems to be very important. For small functioning symptomatic G1 tumours, the aim of the ablation is the symptom relief. For non-functioning tumours, the treatment goal is complete ablation of the lesion as confirmed by imaging.

Including the case here described, this technique achieved clinical success (complete symptom resolution) in 100% of 19 functioning tumours with a mean follow-up of 13.6 mo (range 2-38). Ethanol ablation is less effective for non-functioning tumours with a reported success (complete radiological ablation) of 70% (7/10 tumours were ablated, one lost to follow-up) with a mean follow-up of 13.4 mo (range 3-24) (Table 2). The reason is unclear but it might be due to a “debulking” effect in functioning ones, resulting in loss of endocrine secretion, although with persistent viable tissue, or to a more aggressive histological grading of non-functioning tumours. Unfortunately, lesion grading was not available in most of the reviewed cases.

Few early complications (within one week) are reported: 7 mild pancreatitis cases were observed (16.2%) out of 43 procedures. One (2.3%) major early complication was described[13]: A pancreatic necrotic lesion that was likely caused by ethanol effusion. It was managed by laparoscopic necrosectomy.

Two (4.6%) late complications occurred: One hematoma and ulceration of the duodenal wall[14] and main pancreatic duct stricture[21]. These were managed by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and stent placement (Table 3).

| No. of treatment session per tumor | |

| Mean (range) | 1.43 (1-3) |

| Alcohol volume, mL | |

| Mean (range) | 1.83 (0.18-8) |

| Technical success, n (%) | 30/30 (100) |

| Clinical success1, n (%) | |

| Functioning | 19/19 (100) |

| Non functioning2 | 7/10 (70) |

| Adverse events3, n (%) | 11 (25.5) |

| Early (within one week), n (%) | 9 (21) |

| Pancreatic necrotic lesion | 1 (2.3) |

| Mild pancreatitis | 7 (16.2) |

| Abdominal pain | 1 (2.3) |

| Late, n (%) | 2 (4.6) |

| Hematoma and ulceration of the duodenal wall | 1 (2.3) |

| Main pancreatic duct stricture | 1 (2.3) |

| Follow-up, mo | |

| Mean (range) | 13.4 (2-38) |

In our case, we achieved a diagnosis of a non-functioning pNET with moderate dysplasia, grade (G2), established on the basis of biopsy (Ki67 > 5%) in a 58-year-old male who refused surgery. We decided to ablate based both on the grading and the age of the patient. Moreover it is worth noting that FNA cytology may underestimate the staging based on surgical specimens. Physicians should be very cautious in using FNA specimens to classify a tumour as low-grade[22]. Consequently our treatment aimed at the complete ablation of the lesion while sparing the pancreatic parenchyma. The nodule we treated had a cystic central component, which has not yet been described in the literature for pNET EUS-guidance ablation. A tecnique similar to that described for cystic neoplasm ablation (ethanol injection and reaspiration) was used.

In conclusion, based on our case study and literature review, we find that this technique is feasible, relatively safe and efficient when applied to symptom relief in functioning tumours. However, the long-term outcomes remain unknown. For non-functioning tumours, it can provide good results for patients unfit for surgery or for those who refuse surgical resection. Its role in “fit for surgery” patients is still undefined and larger comparative studies with long-term follow-up are needed to assess its role.

The authors describe a procedure of eus guided ethanol ablation along three sessions for a cystic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (pNET).

Incidental focal lesion of the pancreatic tail with endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) “bull’s eye appearance” and peripheral hypervascularization, suspicious for neuroendocrine tumour.

Other focal lesions of the pancreas.

No lab abnormality including levels of carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen, but recent onset of glucose intolerance.

Abdominal ultrasound, endoscopic ultrasound, magnetic resonance, EUS guided FNA.

Neuroendocrine tumor, G2, Ki67 proliferative index > 5%.

The authors treated the patient by EUS-guided ethanol injection along three sessions.

For patients unfit for surgery due to high-risk comorbidity or for those who refuse resection EUS-guided ethanol ablation has been reported in a few cases.

pNETS: Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours; EUS: Endoscopic ultrasound.

The authors find that EUS guided ethanol ablation is relatively safe and efficient for the treatment of pNETs in patients unfit for surgery or for those who refuse surgical resection. Its role in “fit for surgery” patients is still undefined.

A well written paper having a clear endpoint and objectives. The review of the literature is complete and presented in an attractive way.

P- Reviewer: Ghosn M, Sadik R S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Clift AK, Frilling A. Management of patients with hepatic metastases from neuroendocrine tumors. Ann Saudi Med. 2014;34:279-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | de Baere T, Deschamps F, Tselikas L, Ducreux M, Planchard D, Pearson E, Berdelou A, Leboulleux S, Elias D, Baudin E. GEP-NETS update: Interventional radiology: role in the treatment of liver metastases from GEP-NETs. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;172:R151-R166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Metz DC, Jensen RT. Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors: pancreatic endocrine tumors. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1469-1492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 637] [Cited by in RCA: 542] [Article Influence: 31.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Partelli S, Maurizi A, Tamburrino D, Baldoni A, Polenta V, Crippa S, Falconi M. GEP-NETS update: a review on surgery of gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Eur J Endocrinol. 2014;171:R153-R162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhang WY, Li ZS, Jin ZD. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided ethanol ablation therapy for tumors. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3397-3403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | de Wilde RF, Edil BH, Hruban RH, Maitra A. Well-differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: from genetics to therapy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9:199-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bettini R, Partelli S, Boninsegna L, Capelli P, Crippa S, Pederzoli P, Scarpa A, Falconi M. Tumor size correlates with malignancy in nonfunctioning pancreatic endocrine tumor. Surgery. 2011;150:75-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Falconi M, Zerbi A, Crippa S, Balzano G, Boninsegna L, Capitanio V, Bassi C, Di Carlo V, Pederzoli P. Parenchyma-preserving resections for small nonfunctioning pancreatic endocrine tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1621-1627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pitt SC, Pitt HA, Baker MS, Christians K, Touzios JG, Kiely JM, Weber SM, Wilson SD, Howard TJ, Talamonti MS. Small pancreatic and periampullary neuroendocrine tumors: resect or enucleate? J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1692-1698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wiechowska-Kozłowska A, Boer K, Wójcicki M, Milkiewicz P. The efficacy and safety of endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis for treatment of pain in patients with pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:503098. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jin Z, Du Y, Li Z, Jiang Y, Chen J, Liu Y. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided interstitial implantation of iodine 125-seeds combined with chemotherapy in the treatment of unresectable pancreatic carcinoma: a prospective pilot study. Endoscopy. 2008;40:314-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jürgensen C, Schuppan D, Neser F, Ernstberger J, Junghans U, Stölzel U. EUS-guided alcohol ablation of an insulinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:1059-1062. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Muscatiello N, Salcuni A, Macarini L, Cignarelli M, Prencipe S, di Maso M, Castriota M, D’Agnessa V, Ierardi E. Treatment of a pancreatic endocrine tumor by ethanol injection guided by endoscopic ultrasound. Endoscopy. 2008;40 Suppl 2:E258-E259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Deprez PH, Claessens A, Borbath I, Gigot JF, Maiter D. Successful endoscopic ultrasound-guided ethanol ablation of a sporadic insulinoma. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2008;71:333-337. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Vleggaar FP, Bij de Vaate EA, Valk GD, Leguit RJ, Siersema PD. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided ethanol ablation of a symptomatic sporadic insulinoma. Endoscopy. 2011;43 Suppl 2 UCTN:E328-E329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Levy MJ, Thompson GB, Topazian MD, Callstrom MR, Grant CS, Vella A. US-guided ethanol ablation of insulinomas: a new treatment option. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:200-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Schnack C, Hansen CØ, Beck-Nielsen H, Mortensen PM. Treatment of insulinomas with alcoholic ablation. Ugeskr Laeger. 2012;174:501-502. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Bor R, Farkas K, Bálint A, Molnár T, Nagy F, Valkusz Z, Sepp K, Tiszlavicz L, Hamar S, Szepes Z. [Endoscopic ultrasound-guided ethanol ablation: an alternative option for the treatment of pancreatic insulinoma]. Orv Hetil. 2014;155:1647-1651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Qin SY, Lu XP, Jiang HX. EUS-guided ethanol ablation of insulinomas: case series and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93:e85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Paik WH, Seo DW, Dhir VK, Wang HPO. Mo1373 EUS-Guided Ethanol Ablation of Small Solid Pancreatic Neoplasm. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79 Suppl 5:Page AB413. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Park do H, Choi JH, Oh D, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided ethanol ablation for small pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: results of a pilot study. Clin Endosc. 2015;48:158-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Vinayek R, Capurso G, Larghi A. Grading of EUS-FNA cytologic specimens from patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: it is time move to tissue core biopsy? Gland Surg. 2014;3:222-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |