Published online Aug 10, 2016. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v8.i15.533

Peer-review started: March 24, 2016

First decision: May 17, 2016

Revised: May 23, 2016

Accepted: June 14, 2016

Article in press: June 16, 2016

Published online: August 10, 2016

Processing time: 134 Days and 14.7 Hours

Between April 2013 and October 2015, 6 patients developed periampullary duodenal or jejunal/biliary leaks after major abdominal surgery. In all patients, percutaneous drainage of the collection or re-operation with primary surgical repair was attempted at first but failed. A fully covered enteral metal stent was placed in all patients to seal the leak. Subsequently, we cannulated the common bile duct and, in some cases, and the main pancreatic duct inserting hydrophilic guidewires through the stent after dilating the stent mesh with a dilatation balloon or breaking the meshes with Argon Plasma Beam. Finally, we inserted a fully covered biliary metal stent to drain the bile into the lumen of the enteral stent. In cases of normal proximal upper gastrointestinal anatomy, a pancreatic plastic stent was also inserted. Oral food intake was initiated when the abdominal drain outflow stopped completely. Stent removal was scheduled four to eight weeks later after a CT scan to confirm the complete healing of the fistula and the absence of any perilesional residual fluid collection. The leak resolved in five patients. One patient died two days after the procedure due to severe, pre-existing, sepsis. The stents were removed endoscopically in four weeks in four patients. In one patient we experienced stent migration causing small bowel obstruction. In this case, the stents were removed surgically. Four patients are still alive today. They are still under follow-up and doing well. Bilio-enteral fully covered metal stenting with or without pancreatic stenting was feasible, safe and effective in treating postoperative enteral leaks near the biliopancreatic orifice in our small series. This minimally invasive procedure can be implemented in selected patients as a rescue procedure to repair these challenging leaks.

Core tip: Despite the small number of patients treated, the results of our experience seem promising. Early total fluid diversion with bilio-enteric fully covered metal stent, and plastic pancreatic stent when necessary, is a feasible, safe, effective and minimally invasive endoscopic procedure for postoperative duodenal leaks/fistulas. It is a reasonable option when primary surgical repair or other surgical treatment has failed. Moreover, our treatment could be offered as a first line treatment in patients with poor clinical status avoiding surgery altogether.

- Citation: Mutignani M, Dioscoridi L, Dokas S, Aseni P, Carnevali P, Forti E, Manta R, Sica M, Tringali A, Pugliese F. Endoscopic multiple metal stenting for the treatment of enteral leaks near the biliary orifice: A novel effective rescue procedure. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2016; 8(15): 533-540

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v8/i15/533.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v8.i15.533

Traumatic, anastomotic and staple line leaks are serious complications after upper gastrointestinal surgery. In particular, the management of patients with duodenal leaks close to the papilla is demanding and complex. The same is true for biliary leaks resulting from biliary anastomotic dehiscence after duodenopancreatectomy. These patients rapidly become poor surgical candidates especially if specific treatment is delayed and sepsis is well established. Furthermore, direct surgical repair of leaks in septic patients commonly yields unsatisfactory results[1].

Duodenal and biliary stenting with covered metal stents is a well established palliative treatment for malignant duodenal and biliary strictures[2,3] and for postoperatory gastrointestinal leaks[4,5].

Combined enteral, biliary and pancreatic stenting for the closure of duodenal and bilio-enteric fistulas has never been reported.

We describe herein our experience along with technical details of combined enteral, biliary and pancreatic stenting with fully covered metal stents in six patients with postoperative, high output enterocutaneous fistulas in close proximity to the papilla or the surgically created biliary orifice.

With the following endoscopic procedure we aim to heal the fistula by diverting all fluids away from the leak preserving normal biliopancreatic flow at the same time.

All procedures were performed under propofol sedation and appropriate patient monitoring in the endoscopic retrograde pancreatic duct suite. All patients agreed to the procedure after thorough explanation of the treatment plan.

All patients have either abdominal percutaneous or surgical drains placed. The first step is to perform a cholangiopancreatography. This helps us locate the bilio/pancreatic orifice at a later stage. When a native papilla is present we proceed with endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy to facilitate cannulation later. In patients with normal upper gastrointestinal anatomy we used therapeutic duodenoscopes (ED-3490TK, Pentax) and in post pancreaticoduodenectomy patients we opted for pediatric colonoscopes (EC38-i10F, Pentax).

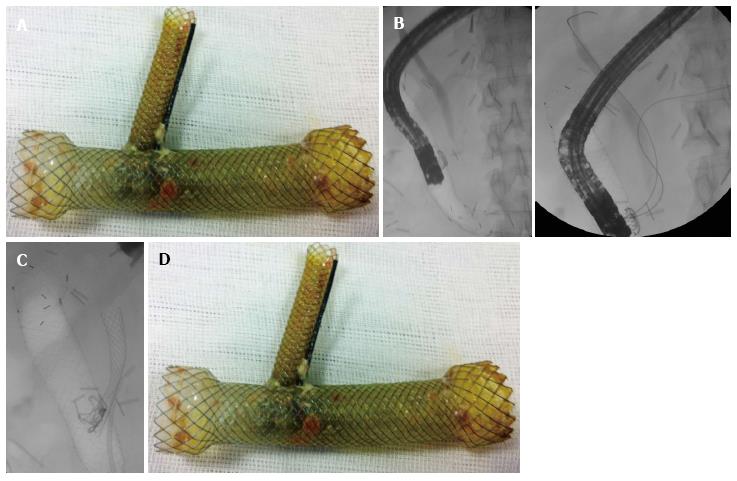

After opacification of the ducts, we insert a fully covered enteral metal stent through the scope. We used the NITI-S (Taewong Medical, Seoul, South Korea) fully covered metal stents with diameter of 20 mm, and length enough to cover the perforation and extend at least 2 cm both proximally and distally. After the enteral stent was placed, we gently performed trans-stent duodenoscopy, trying to avoid stent displacement (Figure 1A). Once into the stent, under fluoroscopy, we re-cannulated both the common bile duct and the main pancreatic duct, using a hydrophilic straight guidewire (Delta, Cook) through a double-lumen sphincterotome (CCPT-25 CannulaTome, Cook). After successful cannulation we leave in place the two guidewires (one for each duct) passing through the covering membrane of the stent (Figure 1B). Before biliopancreatic stenting, we dilated the stent meshes with an 8 mm dilatation balloon (Hurricane, Boston Scientific), or enlarged the hole by melting a few stent struts with Argon Plasma Coagulation (APC).

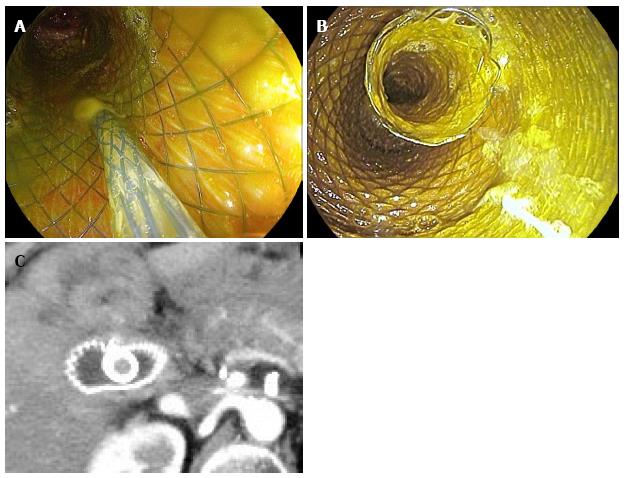

Afterwards biliary and pancreatic stenting was performed. We used fully covered metal stent for the common bile duct (Wallflex, Boston Scientific), 4-6 cm long and 8-10 mm in diameter to accommodate with the width of the common bile duct (Figure 2A). The distal end of the biliary stent was positioned protruding at least 1 cm inside the enteral stent lumen to guarantee stability and complete biliary drainage into the enteral stent (Figure 2B).

Pancreatic stents were plastic 7 Fr × 7 cm stents with antimigration flanges (Figure 1C). These stents were also placed well protruding distally into the enteric stent lumen for the same reasons.

The stents were left in place for a period of four to eight weeks. The abdominal drain output was regularly checked after the procedure. The day after complete outflow stop, patients underwent a CT scan (Figure 2C) to confirm the absence of any residual fluid collection. If imaging confirmed our clinical data, patients were started on a semiliquid diet. Three days later we removed the abdominal drains. During the postprocedural period, non-operated patients continued a semiliquid diet to reduce the risk of stent’s migration. At the scheduled time to remove the stents, we performed a new CT scan. If there was no contraindication, stents were removed en-bloc by grasping and pulling the enteral stent. The study has been approved by our (Niguarda-Ca’ Granda Hospital) Institutional Review Board and our Ethical Committee. All the patients signed the informed consent about the procedure. The entire procedure lasts from 15 to 40 min.

A 66-year-old female patient was admitted to our department due to bilio-enteric anastomotic leak. She had undergone Whipple’s procedure for pancreatic cancer. At first endoscopy a complete dehiscence of the bilio-enteric anastomosis was diagnosed. We inserted a fully covered biliary metal stent (10 mm × 4 cm). A large subphrenic collection rapidly developed because of a complete duodenal wall necrosis around the bilio-enteral anastomosis; so, we removed the biliary stent. In order to fully divert fluids away from the leak we placed a fully covered enteral stent (20 mm × 8 cm) to cover the dehiscence, after draining the collection percutaneously. After bile duct cannulation through the stent mesh, we created a hole at the stent membrane and dilated the stent mesh with a 6 mm balloon. Finally we inserted a fully covered biliary stent (10 mm × 4 cm) through the fenestrated membrane of the enteral stent. The abdominal drain’s output stopped in 3 d and was removed on the fourth day after the procedure. The two stents were removed en bloc 8 wk later. The fistula healed completely and the patient is in good condition 28 mo after the procedure (Table 1).

| Patient (yr/gender) | Original procedure | Indication to treat | Treatment protocol | Success (days to obtain fistula closure) | Removal | F/u (mo) |

| 1 (66/F) | Whipple's procedure for pancreatic adeno Ca | Dehiscence of the bilio-enteric anastomosis | FCESEMS (8 cm × 20 mm) + FCBSEMS (4 cm × 10 mm) | Yes (3) | En bloc endoscopic removal 8 wk later | 28 |

| 2 (57/M) | Whipple’s procedure with pancreatic nelaton tube for main duct IPMN | Dehiscence of the bilioenteric and the pancreatico-jejunal anastomosis | FCESEMS (8 cm × 20 mm) + FCBSEMS (4 cm × 8 mm) + positioning of nelaton tube into enteral stent + FCESEMS (8 cm × 20 mm) | Yes after second stenting (1) | First enteral stenting induced a jejunal perforation A 2nd enteral stenting was performed All stents removed endoscopically 6 wk later | 24 |

| 3 (72/M) | Nephrectomy Liver transplantation 5 yr ago | Duodenal leak after rupture of infected perirenal hematoma | FCESEMS (10 cm × 20 mm) + FCBSEMS (6 cm × 10 mm) + Pancreatic plastic stent (7 Fr × 7 cm) | Pre-existing sepsis Patient died 48 h after procedure | N/A | N/A |

| 4 (68/M) | Right nephrectomy, adrenalectomy and right colectomy for retroperitoneal liposarcoma | Duodenal fistula | FCESEMS (12 cm × 20 mm) (12 cm × 20 mm) + FCBSEMS (6 cm × 8 mm) (4 cm × 10 mm) + Pancreatic plastic stent (7 Fr × 7 cm) | Yes after removal of second set of stents (1) | Stents removed surgically due to migration causing enteral obstruction New stents re-inserted a few days later which were removed endoscopically 4 wk later | 18 |

| 5 (51/M) | Distal duodenal wedge resection for duodenal adenoma with focal adenocarcinoma | Dehiscence of duodenal suture + Biliary fistula at previous T tube placement site | FCESEMS (10 cm × 20 mm) + FCBSEMS (6 cm × 10 mm) + Pancreatic plastic stent (7 Fr × 7 cm) | Yes (1) | All stents removed endoscopically 4 wk later | 36 |

| 6 (56/F) | Cholecystectomy | Duodenal fistula-Duodenal wall erosion from surgical drain | FCESEMS (10 cm × 24 mm) + FCBSEMS (6 cm × 10 mm) + Pancreatic plastic stent (7 Fr × 7 cm) | Yes (1) | All stents removed endoscopically 8 wk later | 6 |

A 57-year-old male patient was admitted to our hospital, for septic fever, three weeks after a Whipple’s procedure for IPMN of the main pancreatic duct. Intra-operatively, a nelaton tube was inserted at the dilated pancreatic duct to facilitate pancreatic flow. A large supra-mesocolic collection was diagnosed at abdominal CT, along with partial complex dehiscence of the bilio-digestive anastomosis associated with duodenal wall necrosis of the surrounding area. We inserted a fully covered enteric stent (20 mm × 8 cm) at the site of the bilio-jejunal anastomosis. Subsequently we punctured the stent membrane and cannulated the common bile duct. We dilated the stent mesh with a 6 mm balloon and finally we inserted a fully covered biliary stent (8 mm × 4 cm) with the distal end of the stent protruding inside the enteric stent. The pancreatic nelaton tube was left in place and drawn well into the lumen of the enteric stent. Four days after the procedure, bile appeared at the abdominal drain. This was due to enteral perforation induced by pressure necrosis from the distal end of the stent. So, we inserted a second fully-covered enteric stent (20 mm × 8 cm) to cover and overpass the enteral perforation. Six weeks later all stents were removed successfully. The leak healed completely and the patient is doing well 24 mo after the procedure (Table 1).

A 72-year-old male patient was admitted to our hospital for the treatment of a refractory duodenal fistula. This fistula developed as a complication of an infected perirenal hematoma after partial nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma. His past history was remarkable for liver transplantation five years before. At first, surgical drains were placed to drain the hematoma along with total parenteral nutrition and antibiotics. Following fistula persistence, 5 d later, primary surgical repair was attempted but ultimately failed. A new surgical attempt to repair the leak was performed with pyloric exclusion and gastrojejunostomy. Unfortunately this procedure was also ineffective. The patient was already in critical condition when we inserted a fully covered duodenal stent through the scope (20 mm × 10 cm). Subsequently, we punctured the duodenal stent membrane and cannulated the pancreatic and the biliary ducts. Finally we dilated the stent mesh with a 6 mm balloon and inserted a fully covered biliary stent (10 mm × 6 cm) and a plastic (7 Fr × 7 cm) stent into the pancreatic duct doth protruding well into the duodenal stent. No contrast leak was evident after the procedure. Unfortunately the patient passed away 2 d later due to severe pre-existing sepsis (Table 1).

A 68-year-old male patient underwent right nephroureterectomy, right adrenalectomy, right colectomy and wedge resection of the duodenal wall for a large retroperitoneal liposarcoma involving the above sites. The postoperative course was complicated by high-output duodenal fistula. At first we attempted endoscopic repair with the Ovesco clip but without success. Subsequently we inserted a fully covered TTS duodenal stent (20 mm × 12 cm). After fenestrating the duodenal stent membrane with APC, we inserted a pancreatic plastic stent (7 Fr × 7 cm) and a biliary fully covered stent (8 mm × 6 cm). After 4 wk, we removed the prosthetic complex but the fistula did not heal because of necrosis of the periampullary duodenal wall. Thus, we decided to perform surgical necrosectomy of a retroperitoneal collection trough a lombotomy, we re-inserted enteral (20 mm × 12 cm), biliary (8 mm × 6 cm) and pancreatic stents (7 Fr × 7 cm). Unfortunately, at that time we only had partially covered enteral stent available. The duodenal fistula resolved completely. At a first attempt of stents removal after 4 wk, the prostheses complex was found to be embedded at the pylorus and could not be pulled out. Before a second removal attempt, the stents had migrated distally, causing small bowel obstruction and were extracted surgically. At surgery, we confirmed the complete healing of the duodenal fistula. Postsurgical course was uneventful. The tumour relapsed 18 mo later. The patient underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy and eventually died of postsurgical septic complications (Table 1).

A 51-year-old male patient underwent distal duodenal wedge resection for duodenal adenoma with focal adenocarcinoma. The postoperative course was complicated by duodenal wall dehiscence and biliary leak at the level of a previously placed T-tube. A periduodenal, retroperitoneal infected collection formed rapidly. The collection was drained percutaneously, but the fistula persisted. A first attempt to seal the leaks was performed with an Ovesco clip and a covered biliary stent, but without success. Subsequently we removed the biliary stent, we inserted a fully covered duodenal stent (20 mm × 10 cm) and fenestrated its membrane with APC. Through the aperture we inserted a plastic pancreatic stent (7 Fr × 7 cm) and a fully covered biliary SEMS (10 mm × 6 cm). The leak resolved and the stents were extracted successfully 1 mo later. The patient is doing well 36 mo after the intervention (Table 1).

A 56-year-old female patient was admitted due to post-cholecystectomy duodenal fistula. The surgical drain placed approximately 12 mo ago was found eroding the duodenal wall. The drain was pulled back and an attempt to seal the perforation was undertaken with the Ovesco clip, but without success. Subsequently we placed a fully covered colonic stent (24 mm × 10 cm) with the over the scope modified technique because the duodenum was quite enlarged. The stent membrane was perforated and the mesh was dilated with a 6 mm balloon. Finally, a pancreatic plastic stent (7 Fr × 7 cm) and a fully covered biliary stent (10 mm × 6 cm) were inserted. The stents were removed one month later. The fistula healed and the patient is doing well 6 mo after the procedure (Table 1).

The treatment of postoperative bilio-enteric leaks is complex and challenging. Their optimal management remains controversial. The presence of bile and pancreatic secretions interfere with the healing process. Several treatment strategies are available for these patients. Immediate, primary surgical repair is a reasonable tactic for patients in good clinical condition[6]. Pyloric exclusion has been utilized extensively for traumatic and post-operative duodenal lesions with reportedly mixed results[7-9]. Other less invasive options include cessation of oral intake, total parenteral nutrition, percutaneous collection drainage, nasogastic drain and suction along with antibiotic treatment; but this rarely is enough. Additionally, late surgical re-intervention is often associated with high mortality, especially in patients with advanced sepsis. Overall, the low success rate and the long duration of available treatments maintain and support the research for improved and less invasive alternatives.

Recently, the development of removable fully covered enteric metal stents has expanded our treatment options in several fields. These stents combine two very important attributes. They can be removed endoscopically several weeks after implantation and provide full contact with the underlying mucosa allowing for fluid to flow through the lumen insulating the enteric mucosa at the same time. Indeed, fully covered metal stents have demonstrated advantages and cost-effectiveness over traditional management[1].

Combined bilio-enteric stenting has been reported before, but for other indications. Previous published studies reported on feasibility and effectiveness of combined bilio-enteric metal stenting for the treatment of malignant bilioduodenal strictures in a single or double step procedure[3]. In the field of postoperative duodenal or bilio-enteric anastomotic leaks no reports regarding combined endoscopic bilio-enteric stenting have been published before. In our opinion, in these situations, over-the-scope clipping cannot be used because it creates, especially on duodenal wall, an ischemic damage that, if it is not associated with adeguate repair reaction (by granulation tissue), results in leak’s worsening. In case 4, the presence of necrotic tissue around the duodenal leak does not let the Ovesco to work properly.

The rationale for the proposed treatment is simple. For the leak/fistula to heal we must divert all fluids away from the leak. Fully covered stents can insulate the underlying mucosa. For a random enteral fistula to heal, placing a fully covered metal stent to cover the leak would, in theory, suffice. In the case of duodenal leaks, bile and pancreatic secretions must be taken into account. In order to maintain a dry fistula we need to divert enteric, biliary and pancreatic secretions away from the leak. Fully covered biliary stents and plastic pancreatic stents can effectively accomplish such fluid diversion. A good alternative method is the percutaneous biliary drainage but it could be difficult without intrahepatic ducts dilation, it represents an important discomfort for the patient and comorbidities of this procedure must be considered.

Hitherto, we found no reports on treating bilio-enteric leaks with complete fluid diversion based on endoscopic fully covered metal stenting. Most patients with post-surgical periampullary leaks are treated either surgically with primary repair or with complex, major abdominal procedures often with poor results. Timing is of the essence in these cases. Taking into account that most leaks are usually accompanied by severe sepsis, one can easily explain the disappointing results especially for the case of late surgical intervention. We believe that in selected patients with established sepsis and poor general condition endoscopic total fluid diversion could be offered as a first line of treatment, avoiding surgery. Our good results along with the minimally invasive manipulations and low tissue damage during this intervention support our claim.

Four (cases 1, 3, 4 and 5) out of 6 patients were in septic condition at the time of the endoscopic intervention. Total fluid diversion along with abdominal drainage, antibiotics and general support rapidly improved the clinical condition in most (5/6) of our patients. All five patients quickly resumed oral intake. They demonstrated swift clinical improvement and resolution of the septic collection. Only the three patients with normal upper gastrointestinal anatomy were maintained on semi-liquid diet during stenting period in order to minimize the risk of stent migration (due to the food impaction into the duodenal stent).

One of our patients unfortunately died of pre-existing severe sepsis 48 h after the intervention. He was operated, with no success, twice for the leak, he had a liver transplantation five years ago and was already in extreme sepsis at the time of the endoscopic intervention. We believe that previous unsuccessful interventions along with immunosuppression may have deteriorated his condition to a point of no return.

One known issue with duodenal stents is post stenting acute pancreatitis[10,11]. Direct papillary pressure from the stent resulting in pancreatic juice flow impairment is believed to be the cause of this complication. We encountered no such complication. Pancreatic stenting anyway maintains the pancreatic flow, so in theory pancreatitis is not an expected event. Obstructive jaundice is another theoretical complication after duodenal stenting. Although stenting the common bile duct is not prerequisite for duodenal stenting[12], covered biliary stents maintain biliary flow and ductal patency.

Making holes at the covering membrane of an enteral stent, or enlarging stent interstices with APC is described in the current literature[10,13,14]. After enteral stent placement, we re-cannulate the ducts under fluoroscopy through the stent covering membrane, leaving in place two guidewires. After that, we dilate the stent mesh with a balloon or enlarge the hole with APC and finally we insert biliary fully covered metal stents and pancreatic plastic stents when necessary. This multi-stent complex, besides creating the desirable fluid diversion network, also provides stability for the whole stent complex itself, acting as an antimigration arrangement/mechanism. Indeed, fully covered biliary and enteral stents, especially in the absence of stricture, are prone to migration[15]. Stent migration occurred in one of our patients causing small bowel obstruction. The stents had to be removed surgically.

Our study is a small prospective cohort with no randomization. It is actually a pilot study to assess the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed treatment in postoperative duodenal leaks/fistulas. All interventions were performed by a single, expert operator. It is a complex and technically demanding procedure and this is an important limitation.

In conclusion, despite the small number of patients treated, the results of our experience seem promising. Early total fluid diversion with bilio-enteric fully covered metal stent, and plastic pancreatic stent when necessary, is a feasible, safe, effective and minimally invasive endoscopic procedure for postoperative duodenal leaks/fistulas. It is a reasonable option when primary surgical repair or other surgical treatment has failed. Moreover, our treatment could be offered as a first line treatment in patients with poor clinical status avoiding surgery altogether. Further studies are needed in order to determine the safety and effectiveness of this novel treatment.

The patients present with enteral leaks near the biliary orifice after abdominal surgery.

Enteral leaks near the bilio-pancreatic orifice.

The site of enteral leak is determined by endoscopic retrograde pancreatic duct (ERCP).

White blood cell and polymerase chain reaction monitoring are helpful for diagnosis and reveal if sepsis is present.

Fluid collections at abdominal computed tomography scan and enteral leaks/fistulas at endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography are found.

Enteral leaks involving the bilio-pancreatic orifice.

Triple endoscopic stenting inserting an enteral, a biliary and a pancreatic stent.

This is the first case series about triple endoscopic stenting in these pathological conditions. However, enteral stenting with or without making holes through the stent meshes were previously described.

Biliopancreatic fluid diversion is the key of the present treatment. Timing is important too: if sepsis is present, the prognosis is worse.

This technique is safe and effective as first-line endoscopic treatment in case of enteral leaks near the biliary orifice.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Lorenzo-Zuniga V S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Babor R, Talbot M, Tyndal A. Treatment of upper gastrointestinal leaks with a removable, covered, self-expanding metallic stent. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2009;19:e1-e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jeurnink SM, Steyerberg EW, van Hooft JE, van Eijck CH, Schwartz MP, Vleggaar FP, Kuipers EJ, Siersema PD. Surgical gastrojejunostomy or endoscopic stent placement for the palliation of malignant gastric outlet obstruction (SUSTENT study): a multicenter randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:490-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 358] [Cited by in RCA: 359] [Article Influence: 23.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Mutignani M, Tringali A, Shah SG, Perri V, Familiari P, Iacopini F, Spada C, Costamagna G. Combined endoscopic stent insertion in malignant biliary and duodenal obstruction. Endoscopy. 2007;39:440-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Raimondo D, Sinagra E, Facella T, Rossi F, Messina M, Spada M, Martorana G, Marchesa PE, Squatrito R, Tomasello G. Self-expandable metal stent placement for closure of a leak after total gastrectomy for gastric cancer: report on three cases and review of the literature. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2014;2014:409283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Walsh C, Karmali S. Endoscopic management of bariatric complications: A review and update. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:518-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Girgin S, Gedik E, Yağmur Y, Uysal E, Baç B. Management of duodenal injury: our experience and the value of tube duodenostomy. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2009;15:467-472. [PubMed] |

| 7. | DuBose JJ, Inaba K, Teixeira PG, Shiflett A, Putty B, Green DJ, Plurad D, Demetriades D. Pyloric exclusion in the treatment of severe duodenal injuries: results from the National Trauma Data Bank. Am Surg. 2008;74:925-929. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Fang JF, Chen RJ, Lin BC. Surgical treatment and outcome after delayed diagnosis of blunt duodenal injury. Eur J Surg. 1999;165:133-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Seamon MJ, Pieri PG, Fisher CA, Gaughan J, Santora TA, Pathak AS, Bradley KM, Goldberg AJ. A ten-year retrospective review: does pyloric exclusion improve clinical outcome after penetrating duodenal and combined pancreaticoduodenal injuries? J Trauma. 2007;62:829-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liu SY, Mao AW, Jia YP, Wang ZL, Jiang HS, Li YD, Yin X. Placement of a duodenal stents bridge the duodenal papilla may predispose to acute pancreatitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2014;61:475-479. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Shi-Yi L, Ai-Wu M, Yi-Ping J, Zhen-Lei W, Hao-Sheng J, Yong-Dong L, Xiang Y. Placement of duodenal stents across the duodenal papilla may predispose to acute pancreatitis: a retrospective analysis. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2012;18:360-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Poincloux L, Goutorbe F, Rouquette O, Mulliez A, Goutte M, Bommelaer G, Abergel A. Biliary stenting is not a prerequisite to endoscopic placement of duodenal covered self-expandable metal stents. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:437-445. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Ogura T, Takagi W, Onda S, Sano T, Masuda D, Fukunishi S, Higuchi K. Hole-making technique for the treatment for acute pancreatitis due to placement of a fully covered duodenal metallic stent. Endoscopy. 2015;47 Suppl 1:E486-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Vanbiervliet G, Piche T, Caroli-Bosc FX, Dumas R, Peten EP, Huet PM, Tran A, Demarquay JF. Endoscopic argon plasma trimming of biliary and gastrointestinal metallic stents. Endoscopy. 2005;37:434-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kullman E, Frozanpor F, Söderlund C, Linder S, Sandström P, Lindhoff-Larsson A, Toth E, Lindell G, Jonas E, Freedman J. Covered versus uncovered self-expandable nitinol stents in the palliative treatment of malignant distal biliary obstruction: results from a randomized, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:915-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |