Published online Apr 16, 2015. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i4.381

Peer-review started: November 2, 2014

First decision: December 12, 2014

Revised: December 30, 2014

Accepted: January 15, 2015

Article in press: January 19, 2015

Published online: April 16, 2015

Processing time: 171 Days and 22.3 Hours

Treatment of pancreatic collections has experienced great progress in recent years with the emergence of alternative minimally invasive techniques comparing to the classic surgical treatment. Such techniques have been shown to improve outcomes of morbidity vs surgical treatment. The recent emergence of endoscopic drainage is noteworthy. The advent of endoscopic ultrasonography has been crucial for treatment of these specific lesions. They can be characterized, their relationships with neighboring structures can be evaluated and the drainage guided by this technique has been clearly improved compared with the conventional endoscopic drainage. Computed tomography is the technique of choice to characterize the recently published new classification of pancreatic collections. For this reason, the radiologist’s role establishing and classifying in a rigorously manner the collections according to the new nomenclature is essential to making therapeutic decisions. Ideal scenario for comprehensive treatment of these collections would be those centers with endoscopic ultrasound and interventional radiology expertise together with hepatobiliopancreatic surgery. This review describes the different types of pancreatic collections: acute peripancreatic fluid collection, pancreatic pseudocysts, acute necrotic collection and walled-off necrosis; the indications and the contraindications for endoscopic drainage, the drainage technique and their outcomes. The integrated management of pancreatic collections according to their type and evolution time is discussed.

Core tip: The interventional endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) development has become in recent years as the first therapeutic alternative for the management of pancreatic collections. The great advantage of EUS is the possibility to in see in real-time image with ultrasound guidance all the material previously introduced into the working channel. The new classification of Atlanta 2012 defines two different evolved pancreatic collections (≥ 4 wk) such as pseudocysts and necrotic encapsulated collections. If both types of collections are symptomatic, they would be subsidiaries of treatment. Given their morphological differences, the technique is similar but the stents used and the results generated differ.

- Citation: Ruiz-Clavijo D, Higuera BGL, Vila JJ. Advances in the endoscopic management of pancreatic collections. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 7(4): 381-388

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v7/i4/381.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v7.i4.381

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a potentially life-threatening disease with a wide spectrum of severity, representing an acute inflammation of the pancreas that may be triggered by a variety of etiologies. After the initial etiologic insult, the activation of pancreatic enzymes occurs in the gland itself, triggering a process of the pancreas self-digestion accompanied by inflammation. This phenomenon leads a repairing and healing process or, less commonly, a systemic inflammatory response that can cause disease in other systems (circulatory, respiratory or renal) promoting the development of organ failure and even death of patient[1]. AP prevalence is increasing, leading to a significant consumption of medical resources[2].

In Atlanta symposium in 1992 a global consensus and a classification system universally applicable for AP was discussed[3]. However, some of these definitions have proved somewhat confusing, and the better understanding of the pathophysiology of organ failure and the development of pancreatic necrosis and the better progress in diagnostics imaging methods have forced a revision of the original classification of Atlanta[4].

An important and illuminating compilation of the terminology of local complications of AP has been established. Four types of collections based on content and time evolution have been defined. These collections are called acute peripancreatic fluid collection, pancreatic pseudocyst, acute necrotic collection and encapsulated necrosis or walled-off necrosis. This new classification represents a breakthrough and facilitates therapeutic decisions in these patients.

The aim of this review is to perform an update of endoscopic management of each of these collections, evaluating the endoscopic treatment role in their comprehensive management.

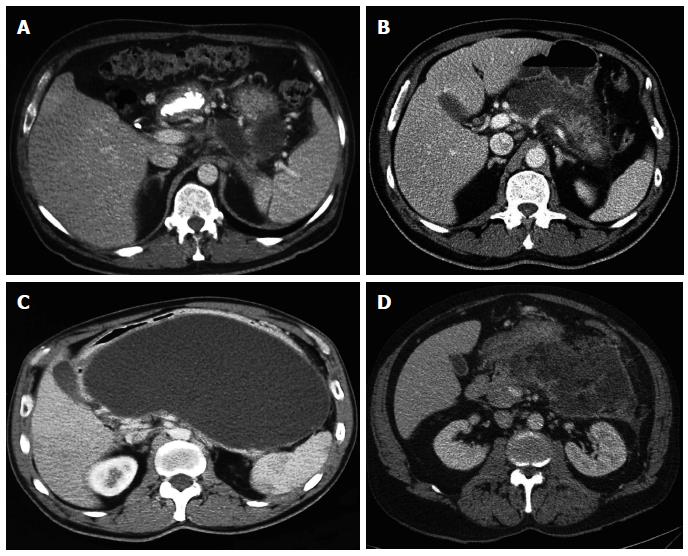

According to the new classification of Atlanta 2012, pancreatic collections can be classified depending to their content, purely liquid or with associate necrosis, and its evolution time, greater or less than 4 wk. Therefore, four types of pancreatic collections can be found.

Acute peripancreatic fluid collection (Figure 1A): is developed in the first phase of AP and characterized by flowing purely liquid homogeneous collections on CT, with no wall defined. It is confined to normal retroperitoneal fascial planes and can be multiple. Most of these collections resolve spontaneously in the first weeks after the AP. In addition to its spontaneous resolution usually it remain sterile[5].

Pancreatic pseudocysts (Figure 1C): it develops when acute pancreatic fluid collection persists more than 4 wk. A well-defined wall is usually generated and they rename pancreatic pseudocyst, presenting high liquid content in amylase and other pancreatic enzymes. The pancreatic pseudocyst is considered to be formed by obstruction or disruption of the main duct or secondary branches, which facilitates its chronicity. The development of pancreatic pseudocyst in the setting of AP on healthy pancreas is rare, most frequently it develops within chronic pancreatitis. In a recent prospective observational study that included 302 patients with AP, acute peripancreatic fluid collection was developed in 129 (42.7%). Among them, pancreatic pseudocyst was developed only in 19 (14.7%). In 90 patients (69.8%) there was spontaneous resolution of acute peripancreatic fluid collection and the other 20 patients (15.5%) failed to complete the follow-up. Regarding to the 19 patients with pancreatic pseudocyst, spontaneous resolution occurred during follow-up in 5 patients (26.3%), a decrease in size in 11 (57.9%) and finally in another patient the monitoring could not be completed. Two patients developed infection with pancreatic pseudocyst requiring percutaneous treatment in one case, and endoscopic drainage on the other[6]. Thus, the percentage of pseudocysts requiring treatment is small.

Acute necrotic collection (ANC) (Figure 1B): it is developed during the first 4 wk of AP evolution and it can contain varying amounts of fluid and necrotic tissue. It may be difficult to distinguish from acute peripancreatic fluid collection during the first week of evolution, but then the distinction between the two is clearer. Like pancreatic pseudocyst, acute necrotic collection may be associated with disruption or obstruction of the pancreatic duct.

Walled-off necrosis (WON) (Figure 1D): consisting of a variable number of necrotic tissue encapsulated within a reactive tissue wall, derived from acute necrotic collection encapsulation past 4 wk. A well-defined wall around the collection can be observed in the imaging, whose complete formation typically occurs within 4 wk of AP origin. The percentage of spontaneous resolution of acute necrotic collections and encapsulated necrosis is unknown, so the knowledge of the natural history of all pancreatic collections is not complete[7].

The presence of necrosis in a pancreatic collection is considered an important prognostic marker, the mortality in patients with necrotizing pancreatitis can reach 15% and even 30% in patients with infected necrosis. This infection typically occurs from the second week after the onset of pancreatitis, but can occur at any time during the clinical course[8]. Through Gram staining or culture from material aspirated by percutaneous or endoscopic puncture, the infection can be tested, but also the presence of gas within the acute necrotic collection or encapsulated necrosis by computed tomography can be a good infection diagnostic indicator.

Pancreatic pseudocysts and WON are considered the most often treated collections, having the characteristics and evolution time required for such treatment.

The transmural approach is the most commonly used. Conducting a transpapillary or combined approach will depend on the collection size, its relationship with the pancreatic duct, its location, and underlying disease.

Usually, pigtail stents are used for pseudocysts drainage while for WON covered self-expandable metallic stents are more commonly employed, associated to an inner coaxial pig-tail stent. Futhermore, the use of flushing nasocystic catheter in WON has been reported in several studies with good results[9,10].

To perform an endoscopic treatment of pancreatic collections is accepted in those cases of symptomatic collections, complicated collections with infections and those producing obstructive symptoms in neighboring viscera, such as stomach, duodenum or bile duct obstruction. It is also accepted the prophylactic treatment in collections which produce vascular compression[11].

Endoscopic drainage is contraindicated in unencapsulated collections, those away from gastroduodenal tract (> 1 cm) and collections with vascular pseudoaneurysm, which should be treated by interventional radiology prior to endoscopic drainage. The presence of neovascularization by portal hypertension is considered a relative contraindication[12].

The therapeutic success of endoscopic drainage of pancreatic collections differ in the case of a pseudocyst or an encapsulated necrotic collection.

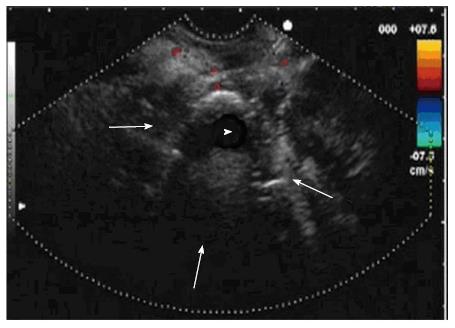

Conventional endoscopy has been deprecated for drainage of pancreatic collections, being overtaken by the therapeutic endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) being reflected in numerous studies[13]. The use of EUS allows a better study of collections and may change management in 5%-9% of cases, either by making an alternative diagnosis or by checking the resolution of pancreatic pseudocyst (Figure 2)[14]. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts is simpler and more resolutive than WON drainage[15].

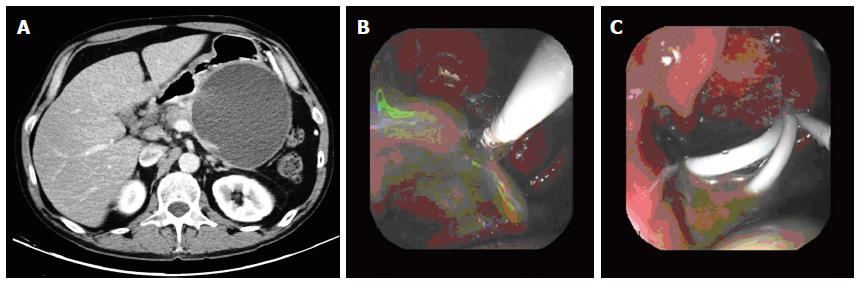

In a recent study involving 117 patients with pancreatic pseudocyst drained endoscopically, pancreatic pseudocyst resolution was achieved in 98.3% of cases. In 87.2% of patients the pancreatic pseudocyst was resolved with only an endoscopic procedure, with no significant differences in treatment success depending on the size (7 or 10 F) or number of stents placed (Figure 3A, B and C)[16].

The recurrence of pancreatic pseudocyst after endoscopic drainage is less than 1%, with series with 0% recurrence at two years when ductal pathology associated is treated by transpapillary stent and transmural stents are maintained indefinitely if there is a ductal disconnection syndrome[17].

By contrast, the result of endoscopic drainage of WON is less effective, demonstrating in different series treatment success rates significantly lower[18]. Therapeutic success described in a multicenter Japanese study (JENIPaN) including 57 patients with WON treated with endoscopic necrosectomy was 75% with a median of 5 endoscopic sessions per patient[19]. In 14 patients in whom endoscopic treatment was ineffective, 8 received other percutaneous or surgical treatment, while 6 patients died during the treatment period without achieving WON resolution. In another similar study from Germany involving 93 patients the WON resolution was achieved in 80% of patients[20]. The median of endoscopic sessions to successfully complete the endoscopic treatment in these patients is between 3 and 6 in the different studies.

In a recently published meta-analysis study that included the results of 12 studies with 481 patients presenting infected necrosis treated only with conservative measures, including percutaneous or endoscopic drainage, treatment success was achieved without any necrosectomy in 59% of patients[21].

Currently, it is very difficult to predict which are the WON collections that can be efficiently and safely managed without necrosectomy. In cases of large and anfractuous collections with a large amount of necrosis, necrosectomy is usually required, either by means of retroperitoneal or endoscopic access. Necrosectomy is usually performed when the initial endoscopic drainage has not been effective. Several studies have shown that the therapeutic success of endoscopic treatment depends largely on the amount of necrosis[22,23].

In this regard, a new lumen-apposing metallic stent (AXIOS®, Xlumena, Mountain View, Ca) has been designed recently for draining pancreatic collections proving good effectiveness in different studies. These stents are completely covered and offer a maximum size of 15 mm so endoscopic necrosectomy is allowed in repeated sessions without the need for replacement of the stents[24].

Assessment of pancreatic ductal pathology in all patients with pancreatic pseudocyst or WON is vital, as if the transmural resolution of the collection is not accompanied by a correct diagnosis and treatment of the underlying ductal pathology, the risk of recurrence is high[25]. In this sense, ductal disruption or stenosis should be ruled out. Currently, the least invasive technique for assessing the integrity of the pancreatic duct is secretin enhanced pancreatic MRI. Ductal evaluation by means of ERCP is another recommended option prior to removing the transmural stents. Varadarajulu et al[17] described the presence of ductal disruption in 10 patients and ductal disconnection syndrome in 4 from 18 patients with pancreatic pseudocyst treated endoscopically[17].

Furthermore ERCP is an endoscopic technique which provides the possibility of transpapillary drainage by placing duct stents in addition to a transmural drainage or as monotherapy, mainly in pseudocysts located in the head or body of the pancreas. This approach is considered less traumatic than the transmural. It is accepted that in patients with underlying chronic pancreatitis with pancreatic pseudocyst under 6 cm communicated with the pancreatic duct, a transpapillary drain as monotherapy can be performed[26].

Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic collections is not free of complications. The most frequent are bleeding, perforation, post-procedure infection and migration of the stents.

A prospective study aimed to determine the frequency of these complications included 148 patients with pancreatic collections of mean diameter 92.3 mm drained by EUS[27]. These collections were classified as pancreatic pseudocyst in 72 (48.6%), abscess in 38 (25.7%) and necrosis in 38 patients (25.7%). There was a transgastric fistula perforation in two patients (1.3%) with pancreatic pseudocyst located at the level of the uncinate process. These perforations were not suspected during the procedure, which in both cases was uneventful. In pseudocysts localised at uncinate process level drained transduodenally no perforation occurred. The authors attributed this drilling to a lack of adhesion of pancreatic pseudocyst to the stomach wall despite being at a distance less than 1 cm. It is postulated that after decompression of pancreatic pseudocysts by the stents, it is separated from the stomach due to be originated in uncinate process and stents were housed in the retroperitoneum. Therefore it is recommended to avoid transgastric drainage of pancreatic pseudocyst localized at uncinate process. Other authors have reported perforations related with the use of electrocautery during drainage procedure[28]. For this reason it is recommended to avoid the use of electrocautery during the creation and expansion of the fistula, making a gradual mechanical dilation. The vast majority of these perforations can be managed by conservative measures with antibiotic treatment and nasogastric suction. The need for surgery in these cases is exceptional[29].

The rate of bleeding after endoscopic drainage has decreased dramatically with EUS. In a prospective randomized study comparing drainage of pancreatic pseudocyst by EUS and conventional endoscopy, severe bleeding occurred in two patients (13.3%) drained by conventional endoscopy. One of them died and no cases of bleeding were observed in the group of patients drained with EUS[30]. The intracystic hemorrhage is inaccessible to endoscopic treatment methods, most of them stop spontaneously or by intracystic washing with serum and diluted epinephrine, sometimes requiring treatment by interventional radiology or surgery. The haemorrhage in the fistula tract is more easily treated by endoscopic methods such as sclerosis or hemoclips placement.

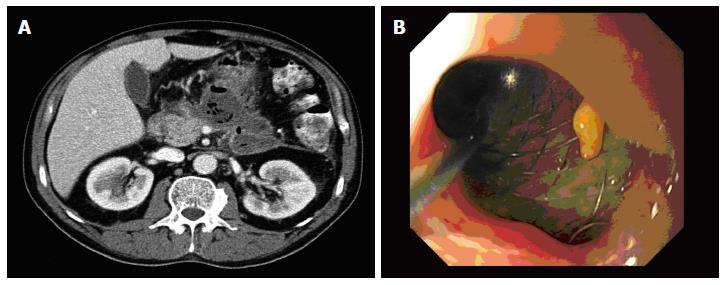

Stent migration is another complication associated with endoscopic drainage of pancreatic collections. Its incidence ranges from less than 1% and 2%[27]. External migration requires only a repetition in the procedure. By contrast, internal migration of stent represents a serious complication and a therapeutic challenge. It is advisable to remove it as early as possible to avoid the fistula closure previously created (Figure 4).

Another complication of endoscopic drainage of pancreatic collections is the infection after endoscopic manipulation, so it is very important the proper drainage. In the series published by Varadarajulu et al[27], infection occurred in 4 patients (2.7%) which was resolved by new endoscopic drainage in two patients and by surgery in the other two[27].

Finally, another potentially fatal complication related to endoscopic necrosectomy is air embolism. It has been described in different multicenter series. In the GEPARD study from Germany that included 93 patients, endoscopic necrosectomy was performed and air embolism occurred in two patients[20]. In JENIPaN study from Japan, there was also an air embolism in a series of 57 patients with endoscopic necrosectomy[19]. Although its usefulness has not been proven, it is now recommended the CO2 distension during necrosectomy to avoid this complication.

Overall, the complication rate is significantly lower with endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocyst drainage compared with WON drainage[31].

In a recent study, Varadarajulu et al[17] compared the results of endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts by endoscopic vs surgical cystogastrostomy with 20 patients in each group observing no complications related to endoscopic treatment[17]. Moreover, in the series of patients undergoing endoscopic necrosectomy previously mentioned, the complication rate was much higher. Thus, in the GEPARD study complications occurred in 26% of patients, with a mortality rate of 7.5% and in the JENIPaN study the complication rate was 33% with an overall mortality of 11%[19,20].

The transpapillary drainage has a complication rate of 16%, especially post-ERCP pancreatitis and infectious complications[32].

Endoscopic treatment of pancreatic collections is an alternative therapy that offers a high success rate with a reasonably low morbidity and mortality compared with other available options. For this reason it is becoming the first-line treatment in many centers. This may vary depending on the experience and resources available so the optimal management of these patients will be in those centers with interventional endoscopist but also interventional radiologist and surgeons specifically devoted to pancreatic surgery. However, endoscopic treatment is not the only therapeutic option in this scenario and is not always the best approach, which will depend on the type of collection and the chronology[33]. Several factors will influence the choice of the initial approach for treatment of pancreatic collections, such as duration of the collection, anatomical factors, previous surgeries, clinical status and integrity of the pancreatic duct.

In the pancreatic pseudocyst treatment, the endoscopic drainage is clearly superior to other therapeutic options, and currently is the therapeutic method of choice[18].

In a recent randomized study, Varadarajulu et al[17] compared the endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts vs surgical drainage and they did not find significant differences regarding treatment success (95% vs 100%), complications (0% vs 10%), reoperation rate (5% vs 5%) or pancreatic pseudocyst recurrence (0% vs 5% ). However, the median hospital stay (2 vs 6) and hospital costs were significantly lower in the endoscopic treatment group[17].

Endoscopic drainage offers advantages over percutaneous or surgical alternatives because it does not require an open incision or placement of an external drainage catheter thereby preventing the onset of complications such as incisional hernia, or fistulae, which can occur in up to 27% of cases[33].

The initial approach of choice in WON collections is less clear because the results are significantly worse with any of the methods used, and sometimes a combination of different techniques is necessary. Traditionally, open surgical necrosectomy has been the treatment of choice in patients with symptomatic or infected pancreatic necrosis. In the past decade minimally invasive therapeutic alternatives have been developed in an attempt to improve the high morbidity (34%-95%) and mortality (11%-39%) of traditional surgical treatment[34].

Currently, it is used the endoscopic transmural approach, percutaneous or a combination of both. It has been also developed less invasive surgical techniques such as video-assisted necrosectomy transretroperitoneal and laparoscopic necrosectomy.

Until recently, there were not enough evidences to confirm that the results obtained with minimally invasive techniques were superior to classical surgery. In 2010, a Dutch multicenter randomized prospective study is published comparing the results obtained by open surgical necrosectomy vs a minimally invasive approach. This approach consisted on percutaneous or endoscopic drainage followed by a second similar drain if there was no improvement produced after 72 h or on video-assisted necrosectomy transretroperitoneal alternatively[35].

In this study, 45 patients with infected pancreatic necrosis were included in the surgical group and 43 in the minimally invasive approach group. Percutaneous drainage was initially performed in 40 patients and endoscopic drainage in one patient. 35% of patients in the minimally invasive approach did not require any necrosectomy. The group of surgical necrosectomy presented a percentage significantly higher of severe complications (69% vs 40%, P = 0.006), there was no difference in mortality rate (16% vs 19%, P = 0.7) and at six months of follow up the patients who undergone surgical necrosectomy had a higher incidence of incisional hernias (24% vs 7%, P = 0.03), diabetes mellitus of recent onset (38% vs 16%, P = 0.02) and need for pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (33% vs 7%, P = 0.002). These results were later confirmed in a meta-analysis including 215 patients with infected necrosis treated with minimally invasive approach and 121 treated with surgical necrosectomy[36].

Two years later the Dutch group published a second study that randomly compared the results of minimal invasive surgical necrosectomy (video assisted transretroperitoneal necrosectomy or laparoscopic necrosectomy) vs endoscopic transgastric necrosectomy including 10 patients with infected necrosis in each group[37]. The proinflammatory response determined by IL-6 was significantly lower after endoscopic necrosectomy compared with surgical necrosectomy (P = 0.004). This aspect is relevant because of organ failure in these patients is due to persistent proinflammatory response[38]. In fact, the incidence multiple organ failure after endoscopic treatment was significantly lower (0% vs 50%, P = 0.03) while the incidence of pancreatic fistula (10% vs 70%, P = 0.02) and the need of pancreatic enzymes (0% vs 50%, P = 0.04) were significantly higher after surgical treatment. Median necrosectomy procedures required were significantly higher in the laparoscopic group (3 vs 1, P = 0.007).

One of the most determining factors in deciding the initial approach is the time evolution time of the pancreatic collection. Here, reclassification of Atlanta has a crucial importance for the endoscopic treatment, since only endoscopic treatment is recommended in those patients with pancreatic pseudocyst or encapsulated necrosis, i.e., in patients with pancreatic collections of more than 4 wk given the risk of complication, inherent in such treatment in earlier stages[4]. However, it is postulated that patients with pancreatic collections presenting clinical deterioration may undergo endoscopic drainage with relative safety from the third week. Probably management of those patients with progressive clinical deterioration requiring invasive treatment before the third week, should begin by percutaneous retroperitoneal drainage with possibility of subsequently adding video-assisted transretroperitoneal necrosectomy or transgastric endoscopic necrosectomy if there is no clinical improvement. Importantly, maximum delay in necrosectomy (> 4 wk) in patients with infected pancreatic necrosis improves treatment outcomes, if necessary, always using less invasive techniques[39]. This concept was demonstrated in a prospective randomized study comparing early surgical necrosectomy (within the first 48-72 h of admission) vs late necrosectomy with conservative management (past 12 d after admission). It was verified that the mortality in the early surgery group reached 56% compared to 27% of the group managed more conservatively with delayed surgery (OR = 3.4). Most of these deaths were due to multiple organ failure and cardiogenic shock[38].

In conclusion, in recent years there have been significant advances in the endoscopic management of pancreatic collections. On the one hand, there are clearer recommendations concerning the most appropriate time to propose an endoscopic treatment of a pancreatic pseudocyst or WON collection. The new classification of Atlanta indicates that endoscopic treatment should wait at least for three or four weeks if imaging tests show maturity of the walls of pancreatic collection. Endoscopic drainage is currently considered as the first treatment of choice for treatment of pancreatic pseudocyst. Furthermore it has been shown that the minimally invasive treatment of the WON offers significant advantages over surgical necrosectomy. In coming years new studies to clarify whether the initial endoscopic approach is better than percutaneous for management of WON and which is the best combination of treatments available for drainage as an alternative rescue.

P- Reviewer: Nentwich MF, Tsuji Y, Yu B S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Working Group IAP/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines. IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2013;13:e1-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1080] [Cited by in RCA: 1032] [Article Influence: 86.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 2. | Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, Crockett SD, McGowan CE, Bulsiewicz WJ, Gangarosa LM, Thiny MT, Stizenberg K, Morgan DR. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1179-1187.e1-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1355] [Cited by in RCA: 1465] [Article Influence: 112.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Bradley EL. A clinically based classification system for acute pancreatitis. Summary of the International Symposium on Acute Pancreatitis, Atlanta, Ga, September 11 through 13, 1992. Arch Surg. 1993;128:586-590. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4306] [Article Influence: 358.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (45)] |

| 5. | Lenhart DK, Balthazar EJ. MDCT of acute mild (nonnecrotizing) pancreatitis: abdominal complications and fate of fluid collections. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:643-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cui ML, Kim KH, Kim HG, Han J, Kim H, Cho KB, Jung MK, Cho CM, Kim TN. Incidence, risk factors and clinical course of pancreatic fluid collections in acute pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:1055-1062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bradley EL. The natural and unnatural history of pancreatic fluid collections associated with acute pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:908-910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Freeman ML, Werner J, van Santvoort HC, Baron TH, Besselink MG, Windsor JA, Horvath KD, vanSonnenberg E, Bollen TL, Vege SS. Interventions for necrotizing pancreatitis: summary of a multidisciplinary consensus conference. Pancreas. 2012;41:1176-1194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 274] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Puri R, Mishra SR, Thandassery RB, Sud R, Eloubeidi MA. Outcome and complications of endoscopic ultrasound guided pancreatic pseudocyst drainage using combined endoprosthesis and naso-cystic drain. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:722-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Siddiqui AA, Dewitt JM, Strongin A, Singh H, Jordan S, Loren DE, Kowalski T, Eloubeidi MA. Outcomes of EUS-guided drainage of debris-containing pancreatic pseudocysts by using combined endoprosthesis and a nasocystic drain. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:589-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Trikudanathan G, Arain M, Attam R, Freeman ML. Interventions for necrotizing pancreatitis: an overview of current approaches. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;7:463-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | de-Madaria E, Abad-González A, Aparicio JR, Aparisi L, Boadas J, Boix E, de-Las-Heras G, Domínguez-Muñoz E, Farré A, Fernández-Cruz L. The Spanish Pancreatic Club’s recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic pancreatitis: part 2 (treatment). Pancreatology. 2013;13:18-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Varadarajulu S, Christein JD, Tamhane A, Drelichman ER, Wilcox CM. Prospective randomized trial comparing EUS and EGD for transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:1102-1111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fockens P, Johnson TG, van Dullemen HM, Huibregtse K, Tytgat GN. Endosonographic imaging of pancreatic pseudocysts before endoscopic transmural drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:412-416. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Chauhan SS, Forsmark CE. Evidence-based treatment of pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:511-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bang JY, Wilcox CM, Trevino JM, Ramesh J, Hasan M, Hawes RH, Varadarajulu S. Relationship between stent characteristics and treatment outcomes in endoscopic transmural drainage of uncomplicated pancreatic pseudocysts. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:2877-2883. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Varadarajulu S, Bang JY, Sutton BS, Trevino JM, Christein JD, Wilcox CM. Equal efficacy of endoscopic and surgical cystogastrostomy for pancreatic pseudocyst drainage in a randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:583-590.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 331] [Article Influence: 27.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Varadarajulu S, Wilcox CM, Latif S, Phadnis M, Christein JD. Management of pancreatic fluid collections: a changing of the guard from surgery to endoscopy. Am Surg. 2011;77:1650-1655. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Yasuda I, Nakashima M, Iwai T, Isayama H, Itoi T, Hisai H, Inoue H, Kato H, Kanno A, Kubota K. Japanese multicenter experience of endoscopic necrosectomy for infected walled-off pancreatic necrosis: The JENIPaN study. Endoscopy. 2013;45:627-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Seifert H, Biermer M, Schmitt W, Jürgensen C, Will U, Gerlach R, Kreitmair C, Meining A, Wehrmann T, Rösch T. Transluminal endoscopic necrosectomy after acute pancreatitis: a multicentre study with long-term follow-up (the GEPARD Study). Gut. 2009;58:1260-1266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 333] [Cited by in RCA: 305] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Mouli VP, Sreenivas V, Garg PK. Efficacy of conservative treatment, without necrosectomy, for infected pancreatic necrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:333-340.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rische S, Riecken B, Degenkolb J, Kayser T, Caca K. Transmural endoscopic necrosectomy of infected pancreatic necroses and drainage of infected pseudocysts: a tailored approach. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:231-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Heiss P, Bruennler T, Salzberger B, Lang S, Langgartner J, Feuerbach S, Schoelmerich J, Hamer OW. Severe acute pancreatitis requiring drainage therapy: findings on computed tomography as predictor of patient outcome. Pancreatology. 2010;10:726-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gornals JB, De la Serna-Higuera C, Sánchez-Yague A, Loras C, Sánchez-Cantos AM, Pérez-Miranda M. Endosonography-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collections with a novel lumen-apposing stent. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1428-1434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Singhal S, Rotman SR, Gaidhane M, Kahaleh M. Pancreatic fluid collection drainage by endoscopic ultrasound: an update. Clin Endosc. 2013;46:506-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tandan M, Nageshwar Reddy D. Endotherapy in chronic pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:6156-6164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Varadarajulu S, Christein JD, Wilcox CM. Frequency of complications during EUS-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collections in 148 consecutive patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:1504-1508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Giovannini M, Pesenti C, Rolland AL, Moutardier V, Delpero JR. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts or pancreatic abscesses using a therapeutic echo endoscope. Endoscopy. 2001;33:473-477. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Will U, Wegener C, Graf KI, Wanzar I, Manger T, Meyer F. Differential treatment and early outcome in the interventional endoscopic management of pancreatic pseudocysts in 27 patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4175-4178. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Varadarajulu S, Eloubeidi MA. Frequency and significance of acute intracystic hemorrhage during EUS-FNA of cystic lesions of the pancreas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:631-635. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Varadarajulu S, Wilcox CM, Tamhane A, Eloubeidi MA, Blakely J, Canon CL. Role of EUS in drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections not amenable for endoscopic transmural drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1107-1119. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Lin H, Zhan XB, Jin ZD, Zou DW, Li ZS. Prognostic factors for successful endoscopic transpapillary drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:459-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Bennett S, Lorenz JM. The role of imaging-guided percutaneous procedures in the multidisciplinary approach to treatment of pancreatic fluid collections. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2012;29:314-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Rodriguez JR, Razo AO, Targarona J, Thayer SP, Rattner DW, Warshaw AL, Fernández-del Castillo C. Debridement and closed packing for sterile or infected necrotizing pancreatitis: insights into indications and outcomes in 167 patients. Ann Surg. 2008;247:294-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, Hofker HS, Boermeester MA, Dejong CH, van Goor H, Schaapherder AF, van Eijck CH, Bollen TL. A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1491-1502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1038] [Cited by in RCA: 1028] [Article Influence: 68.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Cirocchi R, Trastulli S, Desiderio J, Boselli C, Parisi A, Noya G, Falconi M. Minimally invasive necrosectomy versus conventional surgery in the treatment of infected pancreatic necrosis: a systematic review and a meta-analysis of comparative studies. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2013;23:8-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Bakker OJ, van Santvoort HC, van Brunschot S, Geskus RB, Besselink MG, Bollen TL, van Eijck CH, Fockens P, Hazebroek EJ, Nijmeijer RM. Endoscopic transgastric vs surgical necrosectomy for infected necrotizing pancreatitis: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1053-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 506] [Cited by in RCA: 495] [Article Influence: 38.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Mier J, León EL, Castillo A, Robledo F, Blanco R. Early versus late necrosectomy in severe necrotizing pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1997;173:71-75. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Baron TH, Kozarek RA. Endotherapy for organized pancreatic necrosis: perspectives after 20 years. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1202-1207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |