Published online Oct 25, 2015. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i15.1181

Peer-review started: April 30, 2015

First decision: August 16, 2015

Revised: September 1, 2015

Accepted: September 16, 2015

Article in press: September 18, 2015

Published online: October 25, 2015

Processing time: 174 Days and 21.1 Hours

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is used for diagnosis and evaluation of many diseases of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. In the past, it was used to guide a cholangiography, but nowadays it emerges as a powerful therapeutic tool in biliary drainage. The aims of this review are: outline the rationale for endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage (EGBD); detail the procedural technique; evaluate the clinical outcomes and limitations of the method; and provide recommendations for the practicing clinician. In cases of failed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), patients are usually referred for either percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) or surgical bypass. Both these procedures have high rates of undesirable complications. EGBD is an attractive alternative to PTBD or surgery when ERCP fails. EGBD can be performed at two locations: transhepatic or extrahepatic, and the stent can be inserted in an antegrade or retrograde fashion. The drainage route can be transluminal, duodenal or transpapillary, which, again, can be antegrade or retrograde [rendezvous (EUS-RV)]. Complications of all techniques combined include pneumoperitoneum, bleeding, bile leak/peritonitis and cholangitis. We recommend EGBD when bile duct access is not possible because of failed cannulation, altered upper GI tract anatomy, gastric outlet obstruction, a distorted ampulla or a periampullary diverticulum, as a minimally invasive alternative to surgery or radiology.

Core tip: In this minireview, we will discuss about endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage (EGBD) and new interesting endoscopic ultrasound therapeutic biliary methods. We recommend EGBD when bile duct access is not possible because of failed cannulation, altered upper gastrointestinal tract anatomy, gastric outlet obstruction, a distorted ampulla or periampullary diverticulum, as a minimally invasive alternative to surgery or radiology.

- Citation: Guedes HG, Lopes RI, Oliveira JF, Artifon ELA. Reality named endoscopic ultrasound biliary drainage. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 7(15): 1181-1185

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v7/i15/1181.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v7.i15.1181

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is used for diagnosis and evaluation of many diseases of the gastrointestinal tract. In the past, it was used to guide a cholangiography[1], but nowadays it emerges as a powerful therapeutic tool in biliary drainage.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is the procedure of choice for drainage of an obstructed common bile duct (CBD) in patients with distal obstruction. Lower success rates are seen in patients with surgically altered anatomy and neoplastic diseases due to failure to access the duodenum or more difficult duct access[2]. However, EUS-guided biliary drainage (EGBD) may be a viable alternative to ERCP in patients with malignant distal CBD obstruction[3].

In 2001, Giovannini et al[4] performed the first palliative hepaticogastrostomy (HGS) under EUS guidance in a patient with inoperable hepatic hilar obstruction. Recently, experience from EUS-guided biliary duct drainage attempts at 6 international centers was reviewed and showed successful bile duct drainage for all techniques combined in 87% cases[5]. Although performed for almost two decades, during the last five years there was a substantial increase in this type of procedure. These publications suggest that EGBD can provide high levels of technical success with acceptable complication rates[6].

The indications for EGBD include: failed conventional ERCP; altered anatomy; tumor preventing access into the biliary tree; and contra-indication to percutaneous access[7].

If the papilla is accessible, a rendezvous technique (EUS-RV) can be adopted wherein EUS is used to puncture the bile duct and a wire is negotiated through the papilla and further therapy is carried out through ERCP. If the papilla is not accessible then EUS is used to access the bile duct and create a fistula for placement of a stent called the transmural technique[8].

The objectives of this review are: Outline the rationale for EGBD; detail the procedural technique; evaluate the clinical outcomes and limitations of the method; and provide recommendations for the practicing clinician.

In cases of failed ERCP, patients are usually referred for either percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) or surgical bypass. Both these procedures have high rates of undesirable complications. EGBD is an attractive alternative to PTBD or surgery when ERCP fails[9]. In a prospective single-center randomized study, EGBD and PTBD were compared in patients with unresectable malignant biliary obstruction. Technical success and clinical success were 100% in both groups. The complication rate for PTBD was 15.3% and the complication rate for EGBD was 25% (P = 0.2), and the cost of the procedures was similar (7570 USD and 5573 USD respectively, P = 0.39)[10]. The surgical bypass is an option only for patients who are good surgical candidates. Despite the more invasive approach, surgery produced better drainage.

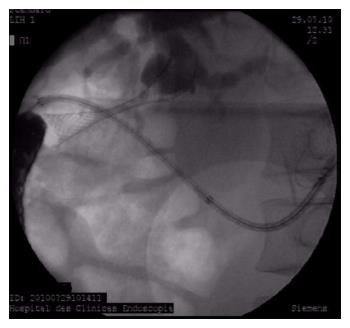

ERCP may be challenging or may fail in certain situations, including post-surgical anatomy, periampullary diverticula, ampullary tumor invasion, and high-grade strictures. EUS-guided interventions may allow access or direct therapy in ERCP failures. In a retrospective single-center cohort study, if the primary intended EUS-guided anterograde cholangiopancreatography (EACP) intervention failed, crossover to other type of EACP therapy was performed, when clinically appropriate- in 95 of 2566 ERCP procedures (3.7%). EUS-guided cholangiography and pancreatography were successful in 97% and 100%, respectively (Figure 1). EUS-RV and ERCP was successful in 75% of biliary procedures and in 56% of pancreatic procedures. Direct EUS-guided therapy was successful in 86% and 75% of biliary and pancreatic procedures, respectively[11]. Another systematic review evaluated the efficacy of EGBD in patients with surgically altered anatomy with 74 cases included for analysis. The pooled technical success, clinical success, and complication rates of all reports with available data were 89.18%, 91.07% and 17.5%, respectively[12].

We recommend surgical bypass for patients with both duodenal and biliary obstructions who are good surgical candidates, but EGBD might be better than PTBD in patients with large volume ascites or patients who refuse external drainage[13].

A gallbladder biliary drainage is necessary in acute cholecystitis with poor performance status and septic shock patients. Jang et al[14] showed that EUS-guided naso-gallbladder drainage via transluminal technique is safe, effective and similar compared to percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage, with a significant lower rate of postoperative pain (1 vs 5; P < 0.001).

Others therapeutics modalities guided by EUS are transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts[8], treatment of distal inflammatory biliary stricture[15], renal biopsy by fine neddle aspiration (EUS-FNA)[16], preoperative fine-needle tattooing insulinoma[17].

EGBD can be performed at two locations: transhepatic (TH), through segment III, when the probe is placed at the stomach cardia and lesser curvature or jejunum (in altered anatomy) or extrahepatic (EH) when the needle access the CBD directly, either using the transmural access from the antral part of the stomach or duodenum[7] (Figure 2). Some endoscopists consider the latter as a route of access to the biliary system due to the anatomical position of the CBD (located in the retroperitoneal space), which might be safer in patients with ascites[18].

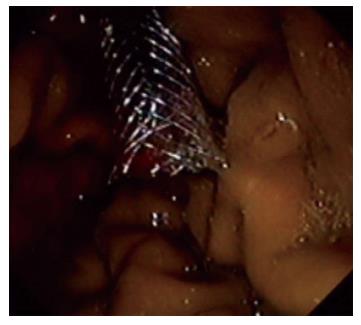

The stent can be inserted in the direction of the papilla (antegrade insertion, AG) or in the direction of the liver (retrograde insertion) (Figure 3). Finally, the drainage route can be transluminal {between the bile duct and either the stomach HGS or the duodenum [choledochoduodenostomy (CDS)]} or transpapillary, which, again, can be antegrade or retrograde (rendezvous, EUS-RV)[19].

The best EGBD route is not defined. Dhir et al[20] compare the success, complications, and duration of hospitalization for patients undergoing EUS-RV by the TH or the EH route. A total of 35 patients were analysed (17 TH, 18 EH). The mean procedure time was significantly longer for the TH group (34.4 vs 25.7 min; P = 0.0004). There was no difference in the technical success (94.1% vs 100%). However, the TH group had a higher incidence of post-procedure pain (44.1% vs 5.5%; P = 0.017), bile leak (11.7 vs 0; P = 0.228), and air under diaphragm (11.7 vs 0; P = 0.228). All bile leaks were small and managed conservatively. Duration of hospitalization was significantly higher for the TH group (2.52 vs 0.17 d; P = 0.015)[20]. Nevertheless, Artifon et al[21] compared the outcomes of 2 non-anatomic EGBD routes: Hepaticogastrostomy (HPG) - 25 patients and CD - 24 patients. HPG and CD techniques were similar in efficacy and safety (Figure 4).

Khashab et al[22] compared outcomes of rendezvous and transluminal techniques. During the study period, 35 patients underwent EGBD (rendezvous n = 13, transluminal n = 20). Technical success was achieved in 33 patients (94%), and clinical success was attained in 32 of 33 patients (97.0%). The mean post-procedure bilirubin level was 1.38 mg/dL in the rendezvous group and 1.33 mg/dL in the transluminal group (P = 0.88). Similarly, length of hospital stay was not different between groups (P = 0.23). There was no significant difference in adverse event rate between rendezvous and transluminal groups (15.4% vs 10%; = 0.64). Long-term outcomes were comparable between groups, with 1 stent migration in the rendezvous group at 62 d and 1 stent occlusion in the transluminal group at 42 d after EGBD. Both rendezvous and direct transluminal techniques seem to be equally effective and safe[22].

According to previous reports, a 19G or 22G FNA needle or needle knife is used to puncture the CBD, followed by the passage of a 0.025-inch or 0.035-inch guidewire was inserted through the needle and looped in the biliary tree[7]. However, there are no randomized controlled trials comparing the outcomes of various FNA needles in the aforementioned procedure[23]. Various devices have been previously described for dilatation of the fistula after puncturing the CBD[23]. The most common devices for transmural tract dilation are the rigid dilator 6 Fr up to 10 Fr, 4-8 mm balloon catheter, diathermic dilator or needle knife. The feasibility of graded dilation in EUS-HGS was superior to that of EUS-CDS[24].

In a series of 101 cases, Poincloux et al[25] placed the EUS in the cardia or the lesser curvature of the stomach and oriented it to view the dilated intrahepatic lateral sector bile ducts. Color Doppler ultrasound was used to confirm absence of vascular structures before EUS-guided puncture through the gastric body. The left bile duct puncture was performed using a 19-gauge access needle and a 0.035- inch super stiff guidewire was introduced through the EUS needle and advanced in an antegrade fashion to the main left bile duct. A hepatogastric fistula was created using a 5.5-Fr wire-guided needle-knife. 6-Fr and 7-Fr tapered biliary dilator catheters to dilate the fistula tract. Under EUS and fluoroscopic view, a stent was placed through the hepatogastrostomy between the main left bile duct and the gastric lumen.

Dhir et al[20] used a 19-gauge needle to puncture in the EUS-RV procedure. Attempt was made to puncture with the echoendoscope in a straight position and the needle pointing in the direction of the CBD. Once biliary access was confirmed by aspiration of 5-10 cc bile, contrast was injected to evaluate the ductal system and, a 0.032-inch hydrophilic angled-tip guide wire was inserted through the needle and directed in an anterograde fashion downstream across the stricture and/or the papilla into the duodenum. Once the guide wire crossed the papilla and looped in the duodenum, the echoendoscope was withdrawn and an ERCP scope was positioned at the papilla. Due to the short length of wire, continuous water injection was used to keep the wire in position. The guide wire was pulled into the biopsy channel of duodenoscope with a snare and ERCP was completed[20].

The stent selection is very important. Plastic stent has a low cost, but, self-expandable metal stents offer superior patency to plastic stents for palliation of malignant distal bile duct obstruction. Even though, the superiority of covered self-expandable metal stents to multiple plastic stents for treatment of benign biliary strictures has not been proven[26]. Covered metal stents may be useful to reduce bile leakage in EGBD.

Most studies about EGBD are single center and based on case reports or small series. Many studies described this procedure with high success rates (more than 90%) and low rate of procedure-related complications (around 19%)[27], however, data from a large multicenter retrospective trial failed to report advantages of any of these techniques[5].

The main risk of EGBD is bile leakage. Complications of all techniques combined included pneumoperitoneum in 5%, bleeding in 11%, bile leak/peritonitis in 10%, and cholangitis in 5%. Complication rates were similar in benign and malignant disease. No significant difference in complication rates was noted when comparing plastic to metal stents, although a trend toward a better outcome was observed for metal stents (P = 0.09). There was a significantly higher incidence of cholangitis in patients with plastic stents (11% vs 3%; P = 0.02)[5].

The use of a needle-knife for fistula dilation was the single risk factor for post procedural adverse events after EGBD. Thus, use of a needle-knife for fistula dilation should be avoided if possible[24], with a risk of creating an unhealthy fistula. This problem does not arise with a cystotome or ring knife fistula creation.

In Dhir et al[19] retrospective multicenter study, death was a major complication reported in 4% of cases. All cases used EUS-RV TH route. Nevertheless, the success rate was equal for the various techniques.

Data involving mostly small series from expertise centers suggest that EGBD can be performed with high therapeutic success (87%) but it might be associated with 10% to 20% morbidity (mostly mild to moderate) and rare serious adverse events[28].

We recommend EGBD when bile duct access is not possible because of failed cannulation, altered upper GI tract anatomy, gastric outlet obstruction, a distorted ampulla, a in situ enteral stent or periampullary diverticulum, as a minimally invasive alternative to surgery or radiology.

P- Reviewer: Altonbary AY S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Jiao XK

| 1. | Wiersema MJ, Sandusky D, Carr R, Wiersema LM, Erdel WC, Frederick PK. Endosonography-guided cholangiopancreatography. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:102-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Farrell J, Carr-Locke D, Garrido T, Ruymann F, Shields S, Saltzman J. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography after pancreaticoduodenectomy for benign and malignant disease: indications and technical outcomes. Endoscopy. 2006;38:1246-1249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dhir V, Itoi T, Khashab MA, Park do H, Yuen Bun Teoh A, Attam R, Messallam A, Varadarajulu S, Maydeo A. Multicenter comparative evaluation of endoscopic placement of expandable metal stents for malignant distal common bile duct obstruction by ERCP or EUS-guided approach. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:913-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Giovannini M, Dotti M, Bories E, Moutardier V, Pesenti C, Danisi C, Delpero JR. Hepaticogastrostomy by echo-endoscopy as a palliative treatment in a patient with metastatic biliary obstruction. Endoscopy. 2003;35:1076-1078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gupta K, Perez-Miranda M, Kahaleh M, Artifon EL, Itoi T, Freeman ML, de-Serna C, Sauer B, Giovannini M. Endoscopic ultrasound-assisted bile duct access and drainage: multicenter, long-term analysis of approach, outcomes, and complications of a technique in evolution. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:80-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Prichard D, Byrne MF. Endoscopic ultrasound guided biliary and pancreatic duct interventions. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;6:513-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kahaleh M, Artifon EL, Perez-Miranda M, Gaidhane M, Rondon C, Itoi T, Giovannini M. Endoscopic ultrasonography guided drainage: summary of consortium meeting, May 21, 2012, San Diego, California. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:726-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gavini H, Lee JH. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided endotherapy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49:185-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Prachayakul V, Aswakul P. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage as an alternative to percutaneous drainage and surgical bypass. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:37-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Artifon EL, Aparicio D, Paione JB, Lo SK, Bordini A, Rabello C, Otoch JP, Gupta K. Biliary drainage in patients with unresectable, malignant obstruction where ERCP fails: endoscopic ultrasonography-guided choledochoduodenostomy versus percutaneous drainage. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:768-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shah JN, Marson F, Weilert F, Bhat YM, Nguyen-Tang T, Shaw RE, Binmoeller KF. Single-operator, single-session EUS-guided anterograde cholangiopancreatography in failed ERCP or inaccessible papilla. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:56-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Siripun A, Sripongpun P, Ovartlarnporn B. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary intervention in patients with surgically altered anatomy. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:283-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Artifon EL, Ferreira FC, Otoch JP. [Endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy for relieving malignant distal biliary obstruction]. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2012;77:31-37. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Jang JW, Lee SS, Song TJ, Hyun YS, Park do H, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH, Yun SC. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided transmural and percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage are comparable for acute cholecystitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:805-811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hao F, Zheng M, Qin M. The effect of endoscopic ultrasonography in treatment of distal inflammatory biliary stricture: a retrospective analysis of 165 cases. Hepatogastroenterology. 2014;61:2177-2180. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Lopes RI, Moura RN, Artifon E. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration for the diagnosis of kidney lesions: A review. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:253-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Leelasinjaroen P, Manatsathit W, Berri R, Barawi M, Gress FG. Role of preoperative endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle tattooing of a pancreatic head insulinoma. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;6:506-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Kahaleh M, Artifon EL, Perez-Miranda M, Gupta K, Itoi T, Binmoeller KF, Giovannini M. Endoscopic ultrasonography guided biliary drainage: summary of consortium meeting, May 7th, 2011, Chicago. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1372-1379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dhir V, Artifon EL, Gupta K, Vila JJ, Maselli R, Frazao M, Maydeo A. Multicenter study on endoscopic ultrasound-guided expandable biliary metal stent placement: choice of access route, direction of stent insertion, and drainage route. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:430-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Dhir V, Bhandari S, Bapat M, Joshi N, Vivekanandarajah S, Maydeo A. Comparison of transhepatic and extrahepatic routes for EUS-guided rendezvous procedure for distal CBD obstruction. United European Gastroenterol J. 2013;1:103-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Artifon EL, Marson FP, Gaidhane M, Kahaleh M, Otoch JP. Hepaticogastrostomy or choledochoduodenostomy for distal malignant biliary obstruction after failed ERCP: is there any difference? Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:950-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Khashab MA, Valeshabad AK, Modayil R, Widmer J, Saxena P, Idrees M, Iqbal S, Kalloo AN, Stavropoulos SN. EUS-guided biliary drainage by using a standardized approach for malignant biliary obstruction: rendezvous versus direct transluminal techniques (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:734-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ogura T, Higuchi K. Technical tips of endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:820-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Park do H, Jang JW, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH. EUS-guided biliary drainage with transluminal stenting after failed ERCP: predictors of adverse events and long-term results. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1276-1284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Poincloux L, Rouquette O, Buc E, Privat J, Pezet D, Dapoigny M, Bommelaer G, Abergel A. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage after failed ERCP: cumulative experience of 101 procedures at a single center. Endoscopy. 2015;47:794-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Baron TH. Best endoscopic stents for the biliary tree and pancreas. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2014;30:453-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Itoi T, Yamao K. EUS 2008 Working Group document: evaluation of EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:S8-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Khashab MA, Dewitt J. EUS-guided biliary drainage: is it ready for prime time? Yes! Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:102-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |