Published online Apr 16, 2014. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v6.i4.101

Revised: December 13, 2013

Accepted: March 3, 2014

Published online: April 16, 2014

Processing time: 176 Days and 20.3 Hours

The aim of this paper is to present and describe transumbilical laparoscopic-assisted appendectomy in children, focusing on its technical aspects and clinical and surgical outcomes. The surgical charts of all patients aged between 0 and 14 years treated with transumbilical laparoscopic-assisted appendectomy admitted to the authors’ institution from January 2009 to September 2013 with a diagnosis of suspected appendicitis following clinical, laboratory and ultrasound findings were reviewed. Operating time, intraoperative findings, need for conversion or for additional trocars, and surgical complications were reported. During the study period, 120 patients aged between 6 and 14 years (mean age: 9.9 years), 73 females (61%) and 47 males (39%), were treated with transumbilical laparoscopic-assisted appendectomy. There were 37 cases of hyperemic appendicitis (subserosal and retrocecal), 74 cases of phlegmonous appendicitis and 9 cases of perforated gangrenous appendicitis. It was not possible to establish a correlation between grade of appendicitis and mean operating time (P > 0.05). Eleven cases (9%) needed the use of one additional trocar, while 8 patients (6%) required conversion to the standard laparoscopic technique with the use of two additional trocars. No patient was converted to the open technique. Transumbilical laparoscopic-assisted appendectomy is a safe technique in children and it could be used by surgeons who want to approach other minimally invasive techniques.

Core tip: Transumbilical video assisted appendectomy in children is safe and useful to approach minimally invasive techniques.

- Citation: Zampieri N, Scirè G, Mantovani A, Camoglio FS. Transumbilical laparoscopic-assisted appendectomy in children: Clinical and surgical outcomes. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2014; 6(4): 101-104

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v6/i4/101.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v6.i4.101

Acute appendicitis is one of the most common causes of acute abdomen in the pediatric age. A clinical approach or laboratory tests resulting in a certain diagnosis for this condition are still to be found. The surgical techniques to perform appendectomy are manifold, ranging from the widely used open technique to more innovative minimally invasive approaches such as NOTES (Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery)[1].

Transumbilical laparoscopic-assisted appendectomy [TULAA], used for the first time on children during the 1990s[2-4], profited from laparoscopy to implement a new minimally invasive approach.

In 1983, Semm described the standard three-port technique for the first time; since then, the minimally invasive approach has gained wide acceptance among pediatric surgeons worldwide[2-5]. The transumbilical laparoscopic-assisted technique (TULAA) combines the advantages of both a good intra-abdominal laparoscopic visualization and the safety and quickness of extracorporeal traditional appendectomy. In 1991, Valla et al[6] reported the first significant case series treated using this technique, although they were all cases of uncomplicated appendicitis. Other authors, including Ohno et al[7], also reported a high number of cases (more than 400 patients) with excellent results, although again all patients had uncomplicated appendicitis.

The purpose of this study is to present the cases recently treated at the authors’ institution for complicated and uncomplicated appendicitis with explanation of the technique used and its technical and pre/postoperative surgical aspects.

At the authors’ institution, all patients reporting abdominal pain with suspected appendicitis without clinical or echographic signs of complicated appendicitis are managed conservatively for the first 12 h. They receive two doses of ampicillin plus sulbactam (50 mg/kg per dose) while their symptoms are monitored and blood tests are performed before opting for either conservative treatment or surgery. The minimally invasive approach currently in use at the authors’ institution is transumbilical in all cases for the camera, standard laparoscopy or TULAA.

At least 30 min before surgery, the patient’s umbilicus is carefully cleansed using a cotton swab impregnated with betadine. Patients do not receive prophylactic antibiotics since they have already received antibiotic treatment.

The patient is placed in the supine position under general anesthesia and mechanical ventilation. Once the patient is asleep, a vesical catheter is placed; the nasogastric tube is not positioned preoperatively but only during surgery if clinically indicated. The umbilicus is disinfected again and a wide sterile surgical area prepared: operation table sheets are placed at the level of the pubo-iliac line and below the rib cage (in order to have quick direct access to the abdominal cavity in case of complications, i.e., massive blood loss). The operating surgeon stands on the left side of the patient, the assistant on the right and the scrub nurse next to the operating surgeon.

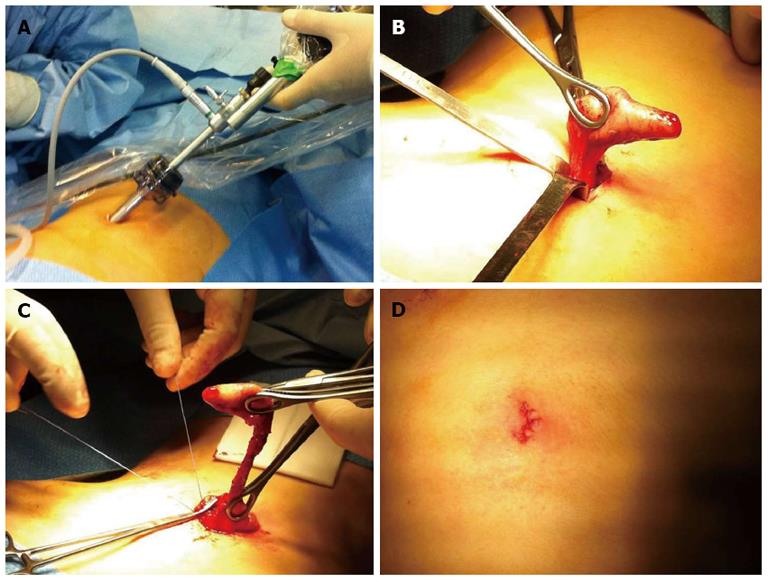

The laparoscopic video display is located on the right caudal side of the patient. The access to the abdominal cavity is achieved using a vertical incision directly through the umbilicus. A 10 mm trocar is then introduced and carbon dioxide (CO2) pneumoperitoneum pressure is maintained at 10 mmHg with a flow of 1.5 L/min. It is paramount to maintain low values of insufflation and intra-abdominal pressure in order to reduce postoperative pain and to prevent cardio-circulatory complications. A zero-degree 10 mm operative telescope is inserted for abdominal examination (Figure 1A). The operation table is placed in the Trendelenburg position and then rotated to the left. From the operating canal of the telescope, a 5 mm traumatic grasper is introduced and the CO2 pneumoperitoneum can be increased up to 12 mmHg; flow is also increased to 2 L/min to compensate for the gas leaks. The grasper is used to identify the appendix and to dissect retroperitoneal adhesions. When the tip of the appendix is freed, it is exteriorized through the umbilicus (Figure 1B). It is important to remember that the pneumoperitoneum needs to be deflated before extracting the appendix (to reduce the space between the cecum and the abdominal cavity and to maintain a moderate traction on the mesoappendix). At this point, a standard extracorporeal appendectomy is performed (Figure 1C). With subserosal, retrocecal or complicated appendicitis, it is possible to introduce one or two additional 3-5 mm trocars for graspers or a cautery hook. The use of more than one additional trocar converts the procedure into a standard laparoscopic appendectomy.

At the end of the procedure, the trocar is inserted again for final inspection (to avoid bleeding) and, if necessary, peritoneal toilet with suction is performed (i.e., with phlegmonous appendicitis or perforated appendicitis). At the end of surgery, the surgeon determines whether it is necessary to use abdominal drainage, applied as in the standard open technique or using one of the trocar ports. The fascial defect is closed with absorbable sutures. The skin suture can also be performed with absorbable stitches (Figure 1D). Naropine 0.2% local anesthetic is usually used at the site of port insertion and a bulky pressure dressing is applied over the umbilical incision.

Postoperative analgesia is administered using ketoprofen or ibuprofen. Paracetamol can also be used.

If there is no perforation, therapy with the same antibiotic is continued for 24 h and then stopped, while all cases of perforated appendicitis receive a regimen of ceftriaxone (100 mg/kg per day in one single administration) plus metronidazole (7.5 mg/kg per dose every 8 h) which is continued until the patient is afebrile for at least 48 h.

Re-feeding can start 12 h after surgery with uncomplicated appendicitis, 24 h in the other cases. Patients are finally discharged from hospital if they have been afebrile for at least 24 h, have no pain and have resumed full oral diet.

The surgical charts of all patients aged between 0 and 14 years treated with TULAA admitted to the authors’ institution from January 2009 to September 2013 with a diagnosis of suspected appendicitis following clinical, laboratory and ultrasound (US) findings were reviewed. Operating time, intraoperative findings, need for conversion or for additional trocars, and surgical complications were reported.

During the study period, 120 patients aged between 6 and 14 years (mean age: 9.9 years), 73 females (61%) and 47 males (39%), were treated with TULAA. There were 37 cases of hyperemic appendicitis (subserosal and retrocecal), 74 cases of phlegmonous appendicitis and 9 cases of perforated gangrenous appendicitis.

The grade of appendicitis was classified as reported in the literature[7]. Mean operating time was 58.6 min (range: 14-135 min), with differences depending on the grade of appendicitis: hyperemic = 55.5 min (range: 25-130 min); phlegmonous = 56.7 min (range: 14-120 min); gangrenous/perforated = 86.2 min (range: 55-135 min). It was not possible to establish a correlation between grade of appendicitis and mean operating time (P > 0.05). Eleven cases (9%) needed the use of one additional trocar, while 8 patients (6%) required conversion to the standard laparoscopic technique with the use of two additional trocars. No patient was converted to the open technique. Mean hospital stay was 3.7 d (range: 2-14 d). There were no cases of intraoperative complications, while postoperatively 5 patients showed umbilical infection (4%) and one patient had intra-peritoneal abscess which was managed conservatively with intravenous antibiotics.

If compared to the standard open technique, minimally invasive techniques have shown many advantages, such as easier exploration of the abdominal cavity, better diagnostic framework and differential diagnosis, as well as reduced postoperative pain. Hospital length of stay is also reduced: paralytic ileus resolves faster in patients who resume food intake early and therefore they are discharged more rapidly. In 1992, Pelosi first suggested the use of transumbilical laparoscopic-assisted appendectomy in adult patients, thus combining a laparoscopic procedure with the basic principles of the open technique and taking advantage from both the traditional and the laparoscopic approach[6-12].

TULAA was first described in pediatric patients in 1998 by C. Esposito and the first cases treated with this technique were reported by Valla et al[6] in 1991.

This video-assisted approach benefits from the laparoscopic technique since enlarged images allow the surgeon to observe the abdominal cavity and easily find the appendix. Also, the use of an operative optical trocar permits the introduction of graspers and cleansing instruments which are important in the most complicated cases of appendicitis. Finally, TULAA involves external appendectomy using the traditional open technique, thus reducing the length and costs of surgery.

Postoperatively, TULAA showed reduction of postoperative pain, shorter duration of pneumoperitoneum and diaphragm stimulation, and further improvement of the cosmetic result of wound scars[7,10-13].

From a technical point of view, TULAA is easier to perform than laparoscopy, with a consequently shorter learning curve for trainee surgeons. The authors’ institution is a reference and excellence center for minimally invasive surgery and their learning curve for laparoscopic appendectomy is of at least 15 surgeries, while for TULAA it is less than 10, regardless of grade of appendicitis. This is because TULAA involves a first laparoscopic approach followed by a traditional open technique for the appendectomy phase, resulting in being safe and efficient at the same time.

In the study series, 9% of cases (11 patients) required an additional port, while only 8 cases (9%) (three cases of gangrenous retrocecal appendicitis) required the placement of 2 additional trocars with conversion to the laparoscopic technique. The possibility of inserting an additional trocar in the most suitable position according to the intraoperative findings allows better management of this condition. Clearly, the learning curve with one trocar reduces surgery length as well as the need for additional trocars. In the authors’ experience, higher complication rates and a more extensive use of an additional trocar occurred with this technique only during the first year of practice. It is also important to remember that TULAA is not an evolution of the laparoscopic technique; it is a different technique and surgeons with a wide laparoscopic experience also used additional trocars in the first cases treated with this technique.

There are many advantages in the use of TULAA: excellent diagnostic and therapeutic approach to the acute abdomen; observation of the entire abdominal cavity; high therapeutic reliability; high versatility; optimal cosmetic result; excellent postoperative recovery; and high feasibility, even in obese patients[13-16].

The current literature does not report real contraindications to the use of this technique apart from those generally indicated for pneumoperitoneum. As for laparoscopy, it is important to remember that insufflation pressure and flow rate must be kept as low as possible, especially in the pediatric age, in order to reduce postoperative pain. Specifically speaking for TULAA, it is necessary to deflate the abdomen before extracting the appendix since this prevents excessive traction on the mesoappendix and facilitates extraction of the appendix through the umbilicus.

According to the authors’ experience, TULAA is a safe, minimally invasive approach in children suffering from acute appendicitis. It is also helpful as a training procedure for other minimally invasive approaches.

P- Reviewers: Rangarajan M, Tagaya N S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Carus T. Current advances in single-port laparoscopic surgery. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2013;398:925-929. |

| 2. | Stephens PL, Mazzucco JJ. Comparison of ultrasound and the Alvarado score for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Conn Med. 1999;63:137-140. |

| 3. | Brennan GD. Pediatric appendicitis: pathophysiology and appropriate use of diagnostic imaging. CJEM. 2006;8:425-432. |

| 4. | Graham JM, Pokorny WJ, Harberg FJ. Acute appendicitis in preschool age children. Am J Surg. 1980;139:247-250. |

| 5. | el Ghoneimi A, Valla JS, Limonne B, Valla V, Montupet P, Chavrier Y, Grinda A. Laparoscopic appendectomy in children: report of 1,379 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29:786-789. |

| 6. | Valla JS, Limonne B, Valla V, Montupet P, Daoud N, Grinda A, Chavrier Y. Laparoscopic appendectomy in children: report of 465 cases. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1991;1:166-172. |

| 7. | Ohno Y, Morimura T, Hayashi S. Transumbilical laparoscopically assisted appendectomy in children: the results of a single-port, single-channel procedure. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:523-527. |

| 8. | de Armas IA, Garcia I, Pimpalwar A. Laparoscopic single port surgery in children using Triport: our early experience. Pediatr Surg Int. 2011;27:985-989. |

| 9. | Amos SE, Shuo-Dong W, Fan Y, Tian Y, Chen CC. Single-incision versus conventional three-incision laparoscopic appendectomy: a single centre experience. Surg Today. 2012;42:542-546. |

| 10. | Lima GJ, Silva AL, Leite RF, Abras GM, Castro EG, Pires LJ. Transumbilical laparoscopic assisted appendectomy compared with laparoscopic and laparotomic approaches in acute appendicitis. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2012;25:2-8. |

| 11. | Valla J, Ordorica-Flores RM, Steyaert H, Merrot T, Bartels A, Breaud J, Ginier C, Cheli M. Umbilical one-puncture laparoscopic-assisted appendectomy in children. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:83-85. |

| 12. | Shekherdimian S, DeUgarte D. Transumbilical laparoscopic-assisted appendectomy: an extracorporeal single-incision alternative to conventional laparoscopic techniques. Am Surg. 2011;77:557-560. |

| 13. | Kagawa Y, Hata S, Shimizu J, Sekimoto M, Mori M. Transumbilical laparoscopic-assisted appendectomy for children and adults. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:411-413. |

| 14. | Sesia SB, Haecker FM, Kubiak R, Mayr J. Laparoscopy-assisted single-port appendectomy in children: is the postoperative infectious complication rate different? J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2010;20:867-871. |

| 15. | Stanfill AB, Matilsky DK, Kalvakuri K, Pearl RH, Wallace LJ, Vegunta RK. Transumbilical laparoscopically assisted appendectomy: an alternative minimally invasive technique in pediatric patients. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2010;20:873-876. |

| 16. | Koontz CS, Smith LA, Burkholder HC, Higdon K, Aderhold R, Carr M. Video-assisted transumbilical appendectomy in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:710-712. |