Published online Nov 16, 2014. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v6.i11.534

Revised: July 15, 2014

Accepted: September 17, 2014

Published online: November 16, 2014

Processing time: 184 Days and 19.2 Hours

Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of the gastrointestinal tract is characterized by the presence of multiple small nodules, normally between between 2 and 10 mm in diameter, distributed along the small intestine (more often), stomach, large intestine, or rectum. The pathogenesis is largely unknown. It can occur in all age groups, but primarily in children and can affect adults with or without immunodeficiency. Some patients have an associated disease, namely, common variable immunodeficiency, selective IgA deficiency, Giardia infection, or, more rarely, human immunodeficiency virus infection, celiac disease, or Helicobacter pylori infection. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia generally presents as an asymptomatic disease, but it may cause gastrointestinal symptoms like abdominal pain, chronic diarrhea, bleeding or intestinal obstruction. A diagnosis is made at endoscopy or contrast barium studies and should be confirmed by histology. Its histological characteristics include markedly hyperplasic, mitotically active germinal centers and well-defined lymphocyte mantles found in the lamina propria and/or in the superficial submucosa, distributed in a diffuse or focal form. Treatment is directed towards associated conditions because the disorder itself generally requires no intervention. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia is a risk factor for both intestinal and, very rarely, extraintestinal lymphoma. Some authors recommend surveillance, however, the duration and intervals are undefined.

Core tip: Published literature about nodular lymphoid hyperplasia includes mainly case reports and small series of patients, there are no reviews concerning this topic. The aim of this large and comprehensive review is to provide current knowledge regarding nodular lymphoid hyperplasia, which may be of great help to clinicians in their daily practice.

- Citation: Albuquerque A. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia in the gastrointestinal tract in adult patients: A review. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2014; 6(11): 534-540

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v6/i11/534.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v6.i11.534

Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia (NLH) of the gastrointestinal tract is characterized by the presence of multiple small nodules, between 2 and 10 mm in diameter. Although it may be detected in the stomach, large intestine or rectum[1], it is more often distributed in the small intestine. Histologically, NLH is defined by markedly hyperplastic, mitotically active germinal centers, and well-defined lymphocyte mantles found in the lamina propria and/or in the superficial submucosa[2].

The incidence is unknown, nevertheless, NLH is considered to be a rare condition in adults[3-6] and published literature includes mainly case reports and small series of patients; whether this relates to endoscopy underreporting or to the true rarity of the condition in adults is unclear[7].

NLH occurs in all age groups[3,8], but primarily in children under ten years of age, when general lymphatic hyperplasia is common[9]. Reported gender distribution of this condition is conflicting[3,10].

NLH has been divided into diffuse nodular lymphoid hyperplasia and focal forms, mainly involving the terminal ileum, rectum, or other sites in the gastrointestinal tract[1,2,11].

Pediatric NLH is generally restricted to the rectum, colon, and terminal ileum, has a benign course, and usually regresses spontaneously[3,12-14]. It has been linked to refractory constipation[15], viral infection, and food allergies[12,13]; however it can be observed in healthy children[16]. In adults, the prognosis is much less certain, and NLH can be divided into those with or without immunodeficiency[17], but, normally, it is associated with immunodeficiency and Giardia infection[18].

The pathogenesis of NLH is largely unknown, but there are some theories that explain this condition and vary according to the presence or absence of associated immunodeficiency.

In immunodeficiency states, in order to compensate for functionally inadequate intestinal lymphoid tissue, NLH may result from an accumulation of plasma-cell precursors due to a maturational defect in the development of B-lymphocytes[11,19].

NLH in the absence of immunodeficiency disorders may be related to immune stimulation of the gut lymphoid tissue. A frequently proposed hypothesis implicates an intestinal antigenic trigger, possibly infectious, that leads to repetitive stimulation and eventual hyperplasia of lymphoid follicles. The frequent association between Giardia infection and NLH suggests this, even in the absence of humoral immunodeficiency[8].

Chiaramonte et al[20] hypothesized that NLH could be a transitional stage in the development of a malignant lesion, or possibly an early lymphomatous lesion. NLH is a risk factor for intestinal lymphoma and there are studies suggesting that lymphoid-associated colorectal mucosa might be the origin of many non-protruding adenomas and consequently of non-protruding early colorectal carcinomas[21].

NLH has been reported in immunocompromised and immunocompetent adult patients.

Approximately 20% of adults with common variable immunodeficiency disease (CVID) are found to have NLH[6,19,22-31]. NLH is also associated with IgA deficiency[22,32-35] and has also been reported in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection[36].

CVID is characterized by the significantly reduced levels of IgG, IgA, and/or IgM, impaired antibody response, with the exclusion of other causes of hypogammaglobulinemia. Patients typically present with recurrent bacterial infections of the upper and lower respiratory tracts, autoimmune disease, granulomatous/lymphoid infiltrative disease, and increased incidence of malignancy. NLH in CVID patients is usually more generalized, involving the proximal small intestine, in addition to the distal ileum and proximal colon[22].

Selective IgA deficiency is the most common primary immunodeficiency, estimated at 1 in 300 to 700 in Caucasians, (IgA < 7 mg/dL with normal or increased levels of other immunoglobulins). The majority of patients are asymptomatic, although the absence of IgA has been associated with recurrent upper respiratory infections (frequently in those with concomitant IgG2 subclass deficiency), autoimmune disorders, allergic diseases and gastrointestinal diseases, namely NLH[37].

Giardia lamblia infection can be associated with NLH[3,10], more commonly in patients with immunodeficiency[38-40], but also in patients without immunodeficiency[4,41]. The association between NLH, hypogammaglobulinemia, and Giardia lamblia infection is known as Herman’s syndrome[11].

The link between NLH and celiac disease seems to be rare[3,32]. It is important to underline that CVID patients may present small-bowel pathology similar to classic celiac sprue, known as “pseudo-celiac” pattern, with short villi, crypt hyperplasia, intraepithelial lymphocytosis, and, in some cases, an increase in apoptotic bodies in crypt epithelial cells. The diagnosis of CVID should be suspected when the number of plasma cells are reduced or absent in the lamina propria, and patients do not produce antibodies to tissue transglutaminase, endomysium, or gliadin. CVID patients typically do not respond to gluten withdrawal and do not express the genes associated with celiac disease, HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8[3,37].

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection has also been implicated in NLH[18,42]. Khuroo et al[18] reported a large cohort of patients (40 patients) with NLH, etiologically related to H. pylori infection. Patients with eradicated H. pylori showed significant clinical response and regression/resolution of the lesions, in contrast to patients with persistent H. pylori infection. The location, in these cases, was limited to the postbulbar duodenum (second and third part) and to the duodenojejunal junction. None of the patients included in this study had an immunodeficiency or giardiasis. NLH was attributed to immune stimulation by prolonged and heavy H. pylori infection.

Familial adenomatous polyposis and Gardner’s syndrome[43-46] was also linked to NLH mainly involving the terminal ileum.

There are also several case reports where no relation with any of the diseases described above was found[2,47,48].

NLH can present as an asymptomatic disease (in the majority of the patients) or with gastrointestinal symptoms like abdominal pain, chronic diarrhea, bleeding, intussusception or intestinal obstruction[5,49].

Massive hyperplasia that can result in intestinal obstruction and intussusception is very rare and mainly described in children[9,50]. H. pylori-induced gastric lymphonodular hyperplasia, causing gastric outlet obstruction, was reported in one case. Anti-H. pylori therapy resulted in eradication and the resolution of signs and symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction[42].

Colón et al[12] published a retrospective analysis including 147 children with NLH and 32% of the cases had bright red blood emission per rectum. In adult patients, NLH uncommonly causes gastrointestinal bleeding and may manifest as massive obscure[51,52], recurrent[53,54] or rectal bleeding[55].

The diagnosis of NLH is established by endoscopy or contrast barium studies and confirmed histologically. There are several other entities that can mimic NLH, and since misdiagnosis could lead to overtreatment of a benign condition, histopathology is fundamental for the diagnosis[5].

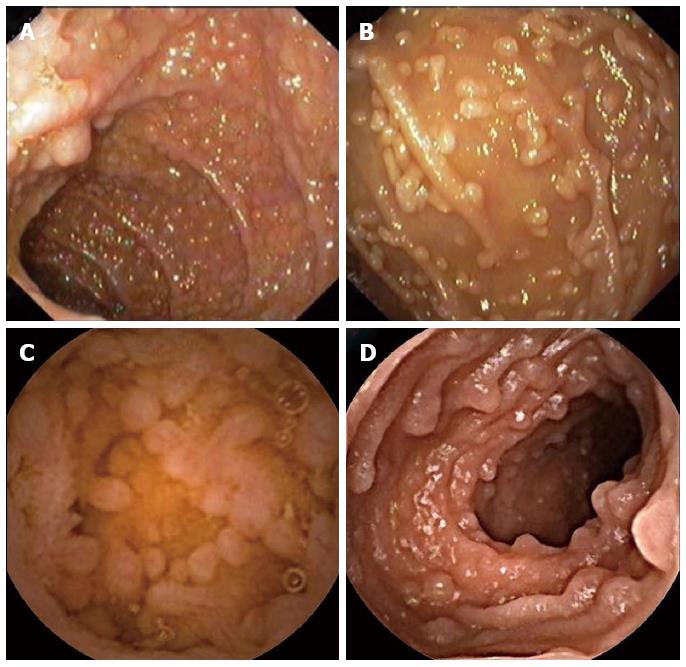

Endoscopic features of NLH include nodules ranging in size from 2 mm to 10 mm, but normally not exceeding 5 mm in diameter (Figure 1A and B). These nodules may present in the stomach, small intestine (terminal ileum is the most common), and colon/rectum. Colonic lymphoid nodules may appear as red macules, as a circumferential target lesions (halo sign), or as raised papules[56,57]. When the large intestine is involved, the rectum is most commonly implicated[58,59]. In NLH involving the colon, the endoscopic appearance can be strikingly similar to polyposis syndromes, including familial adenomatous polyposis, multiple lymphomatous polyposis, juvenile or hamartomatous, polyposis and serrated polyposis syndrome, among others[58]. There is a case report of an adult immunocompetent patient with NLH in a defunctionalized colon, following ileostomy performed because of localized regional ileitis[60]. This had only been previously described in children[61].

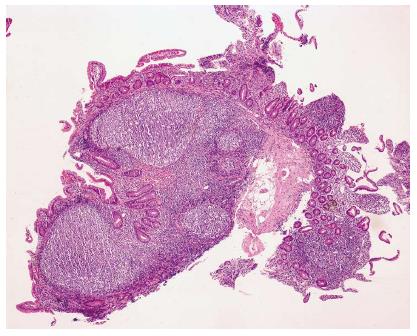

NLH is diagnosed when the following histological criteria (Figure 2) are observed: hyperplasic lymphoid follicles, mitotically active germinal centers with well-defined lymphocytes mantles, and lymphoid follicles localized in the mucosa and/or submucosa[2].

In NLH involving the small bowel, small bowel barium swallow and, mainly, capsule endoscopy are important for the diagnosis, to exclude complications (like lymphoma), and to determine disease extension in the small bowel (Figure 1C and D).

Small bowel barium swallow can be diagnostic by revealing multiple, round-shaped nodular filling defects in the small bowel segments[23].

In the presence of NLH, immunodeficiency (CVID, selective IgA deficiency and HIV infection), giardiasis, celiac disease, and H. pylori infection should be suspected.

In general, colonic NLH is considered of no clinical significance[7,55].

NLH can resemble both clinically and histologically malignant lymphoma[62]. It can be distinguished by the polymorphic nature of the infiltrate, the absence of significant cytologic atypia, and the presence of reactive follicles within the lesion, and by use of immunohistochemical or molecular analysis[1]. Among primary intestinal lymphomas, mantle cell lymphoma is most frequently represented by multiple polypoid lesions[63]; however, less frequently, extranodal marginal zone lymphoma or mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue-MALT[64], and follicular lymphoma[65] also show multiple lymphomatous polyposis.

Gastric involvement is rare[1]. The differential diagnosis of gastric lymphoid lesions includes reactive processes and malignant lymphoma. In such cases, it is important to rule out extranodal marginal zone lymphoma[66]. Some gastric lesions are associated with chronic peptic ulcers, but ulceration is absent or insignificant in focal lesions located in the intestine[1].

Treatment is directed to associated conditions because the disorder itself generally requires no intervention[5].

In both immunodeficient and immunocompetent patients with NLH, the eradication of Giardia often causes the intestinal symptoms to disappear[11]; nevertheless, in most reported cases, successful treatment of the infection did not lead to a regression in the number or size of the lymphoid nodules[24,67], although this also has been described[17].

NLH is a risk factor for both intestinal and, very rarely, extraintestinal lymphoma, previously reported in patients with and without immunodeficiency[2,20,68-77]. The link between extraintestinal lymphoma[4,47,78] and NLH is uncommon. Jonsson et al[78] reported a case of extraintestinal lymphoma associated with NLH, in which, hyperplastic tissue completely disappeared after chemotherapy with remission of the lymphoma and reappearance at relapse.

A study from Japan and Sweden also suggests an association between colonic lymphoid nodules and non-protruding colorectal neoplasia, adenomas, and early carcinomas[21].

Considering the risk of malignant transformation, surveillance capsule endoscopies and small bowel series are recommended by some authors in small bowel NLH[59] however, the duration and intervals of such surveillance are undefined; biopsy of enlarging lymphoid nodules should be performed to exclude lymphomatous transformation[32].

There are several missing pieces in the NLH puzzle, including: epidemiological data (incidence, prevalence, gender distribution), pathogenesis, and clarification about the role that other endoscopic or non-endoscopic procedures have in NLH evaluation, such as, enteroscopy. Most importantly an essential question remains regarding the selection of patients and timing for surveillance.

P- Reviewer: Efthymiou A, Maltz C, Tseng PH S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Ranchod M, Lewin KJ, Dorfman RF. Lymphoid hyperplasia of the gastrointestinal tract. A study of 26 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 1978;2:383-400. |

| 2. | Rambaud JC, De Saint-Louvent P, Marti R, Galian A, Mason DY, Wassef M, Licht H, Valleur P, Bernier JJ. Diffuse follicular lymphoid hyperplasia of the small intestine without primary immunoglobulin deficiency. Am J Med. 1982;73:125-132. |

| 3. | Rubio-Tapia A, Hernández-Calleros J, Trinidad-Hernández S, Uscanga L. Clinical characteristics of a group of adults with nodular lymphoid hyperplasia: a single center experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1945-1948. |

| 4. | Baran B, Gulluoglu M, Akyuz F. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of duodenum caused by giardiasis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:A22. |

| 5. | Schwartz DC, Cole CE, Sun Y, Jacoby RF. Diffuse nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of the colon: polyposis syndrome or normal variant? Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:630-632. |

| 6. | Ajdukiewicz AB, Youngs GR, Bouchier IA. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia with hypogammaglobulinaemia. Gut. 1972;13:589-595. |

| 7. | Colarian J, Calzada R, Jaszewski R. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of the colon in adults: is it common? Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:421-422. |

| 8. | Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 8-1997. A 65-year-old man with recurrent abdominal pain for five years. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:786-793. |

| 9. | Swartley RN, Stayman JW. Lymphoid hyperplasia of the intestinal tract requiring surgical intervention. Ann Surg. 1962;155:238-240. |

| 10. | Canto J, Arista J, Hernández J. [Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of the intestine. Clinico-pathologic characteristics in 11 cases]. Rev Invest Clin. 1990;42:198-203. |

| 11. | Hermans PE, Huizenga KA, Hoffman HN, Brown AL, Markowitz H. Dysgammaglobulinemia associated with nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of the small intestine. Am J Med. 1966;40:78-89. |

| 12. | Colón AR, DiPalma JS, Leftridge CA. Intestinal lymphonodular hyperplasia of childhood: patterns of presentation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1991;13:163-166. |

| 13. | Iacono G, Ravelli A, Di Prima L, Scalici C, Bolognini S, Chiappa S, Pirrone G, Licastri G, Carroccio A. Colonic lymphoid nodular hyperplasia in children: relationship to food hypersensitivity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:361-366. |

| 14. | Webster AD. The gut and immunodeficiency disorders. Clin Gastroenterol. 1976;5:323-340. |

| 15. | Kiefte-de Jong JC, Escher JC, Arends LR, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, Raat H, Moll HA. Infant nutritional factors and functional constipation in childhood: the Generation R study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:940-945. |

| 16. | Tokuhara D, Watanabe K, Okano Y, Tada A, Yamato K, Mochizuki T, Takaya J, Yamano T, Arakawa T. Wireless capsule endoscopy in pediatric patients: the first series from Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:683-691. |

| 17. | Ward EM, Wolfsen HC. Review article: the non-inherited gastrointestinal polyposis syndromes. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:333-342. |

| 18. | Khuroo MS, Khuroo NS, Khuroo MS. Diffuse duodenal nodular lymphoid hyperplasia: a large cohort of patients etiologically related to Helicobacter pylori infection. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:36. |

| 19. | Hermans PE, Diaz-Buxo JA, Stobo JD. Idiopathic late-onset immunoglobulin deficiency. Clinical observations in 50 patients. Am J Med. 1976;61:221-237. |

| 20. | Chiaramonte C, Glick SN. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of the small bowel complicated by jejunal lymphoma in a patient with common variable immune deficiency syndrome. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;163:1118-1119. |

| 21. | Rubio CA. Nonprotruding colorectal neoplasms: epidemiologic viewpoint. World J Surg. 2000;24:1098-1103. |

| 22. | Lai Ping So A, Mayer L. Gastrointestinal manifestations of primary immunodeficiency disorders. Semin Gastrointest Dis. 1997;8:22-32. |

| 23. | Washington K, Stenzel TT, Buckley RH, Gottfried MR. Gastrointestinal pathology in patients with common variable immunodeficiency and X-linked agammaglobulinemia. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1240-1252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Luzi G, Zullo A, Iebba F, Rinaldi V, Sanchez Mete L, Muscaritoli M, Aiuti F. Duodenal pathology and clinical-immunological implications in common variable immunodeficiency patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:118-121. |

| 25. | Atarod L, Raissi A, Aghamohammadi A, Farhoudi A, Khodadad A, Moin M, Pourpak Z, Movahedi M, Charagozlou M, Rezaei N. A review of gastrointestinal disorders in patients with primary antibody immunodeficiencies during a 10-year period (1990-2000), in children hospital medical center. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;2:75-79. |

| 26. | Teahon K, Webster AD, Price AB, Weston J, Bjarnason I. Studies on the enteropathy associated with primary hypogammaglobulinaemia. Gut. 1994;35:1244-1249. |

| 27. | Nagura H, Kohler PF, Brown WR. Immunocytochemical characterization of the lymphocytes in nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of the bowel. Lab Invest. 1979;40:66-73. |

| 28. | Webster AD, Kenwright S, Ballard J, Shiner M, Slavin G, Levi AJ, Loewi G, Asherson GL. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of the bowel in primary hypogammaglobulinaemia: study of in vivo and in vitro lymphocyte function. Gut. 1977;18:364-372. |

| 29. | Khodadad A, Aghamohammadi A, Parvaneh N, Rezaei N, Mahjoob F, Bashashati M, Movahedi M, Fazlollahi MR, Zandieh F, Roohi Z. Gastrointestinal manifestations in patients with common variable immunodeficiency. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2977-2983. |

| 30. | Said-Criado I, Gil-Aguado A. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia in common variable immunodeficiency. Lancet. 2014;383:e2. |

| 31. | Bästlein C, Burlefinger R, Holzberg E, Voeth C, Garbrecht M, Ottenjann R. Common variable immunodeficiency syndrome and nodular lymphoid hyperplasia in the small intestine. Endoscopy. 1988;20:272-275. |

| 32. | Postgate A, Despott E, Talbot I, Phillips R, Aylwin A, Fraser C. An unusual cause of diarrhea: diffuse intestinal nodular lymphoid hyperplasia in association with selective immunoglobulin A deficiency (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:168-19; discussion 169. |

| 33. | Jacobson KW, deShazo RD. Selective immunoglobulin A deficiency associated with modular lymphoid hyperplasia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1979;64:516-521. |

| 34. | Piaścik M, Rydzewska G, Pawlik M, Milewski J, Furmanek MI, Wrońska E, Polkowski M, Butruk E. Diffuse nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of the gastrointestinal tract in patient with selective immunoglobulin A deficiency and sarcoid-like syndrome--case report. Adv Med Sci. 2007;52:296-300. |

| 35. | Joo M, Shim SH, Chang SH, Kim H, Chi JG, Kim NH. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia and histologic changes mimicking celiac disease, collagenous sprue, and lymphocytic colitis in a patient with selective IgA deficiency. Pathol Res Pract. 2009;205:876-880. |

| 36. | Levendoglu H, Rosen Y. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of gut in HIV infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:1200-1202. |

| 37. | Agarwal S, Mayer L. Diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal disorders in patients with primary immunodeficiency. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1050-1063. |

| 38. | Olmez S, Aslan M, Yavuz A, Bulut G, Dulger AC. Diffuse nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of the small bowel associated with common variable immunodeficiency and giardiasis: a rare case report. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2014;126:294-297. |

| 39. | de Weerth A, Gocht A, Seewald S, Brand B, van Lunzen J, Seitz U, Thonke F, Fritscher-Ravens A, Soehendra N. Duodenal nodular lymphoid hyperplasia caused by giardiasis infection in a patient who is immunodeficient. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:605-607. |

| 40. | Onbaşi K, Günşar F, Sin AZ, Ardeniz O, Kokuludağ A, Sebik F. Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) presenting with malabsorption due to giardiasis. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2005;16:111-113. |

| 41. | Ward H, Jalan KN, Maitra TK, Agarwal SK, Mahalanabis D. Small intestinal nodular lymphoid hyperplasia in patients with giardiasis and normal serum immunoglobulins. Gut. 1983;24:120-126. |

| 42. | Misra SP, Misra V, Dwivedi M, Singh PA. Helicobacter pylori-induced lymphonodular hyperplasia: a new cause of gastric outlet obstruction. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:1191-1194. |

| 43. | Shull LN, Fitts CT. Lymphoid polyposis associated with familial polyposis and Gardner’s syndrome. Ann Surg. 1974;180:319-322. |

| 44. | Dorazio RA, Whelan TJ. Lymphoid hyperplasia of the terminal ileum associated with familial polyposis coli. Ann Surg. 1970;171:300-302. |

| 45. | Thomford NR, Greenberger NJ. Lymphoid polyps of the ileum associated with Gardner’s syndrome. Arch Surg. 1968;96:289-291. |

| 46. | Venkitachalam PS, Hirsch E, Elguezabal A, Littman L. Multiple lymphoid polyposis and familial polyposis of the colon: a genetic relationship. Dis Colon Rectum. 1977;21:336-341. |

| 47. | Monsanto P, Lérias C, Almeida N, Lopes S, Cabral JE, Figueiredo P, Silva M, Julião M, Gouveia H, Sofia C. Intestinal nodular lymphoid hyperplasia and extraintestinal lymphoma--a rare association. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2012;75:260-262. |

| 48. | Matuchansky C, Touchard G, Lemaire M, Babin P, Demeocq F, Fonck Y, Meyer M, Preud’Homme JL. Malignant lymphoma of the small bowel associated with diffuse nodular lymphoid hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:166-171. |

| 49. | Garg V, Lipka S, Rizvon K, Singh J, Rashid S, Mustacchia P. Diffuse nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of intestine in selective IgG 2 subclass deficiency, autoimmune thyroiditis, and autoimmune hemolytic anemia: case report and literature review. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2012;21:431-434. |

| 50. | Chandra S. Benign nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of colon: a report of two cases. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2003;22:145-146. |

| 51. | Shuhaiber J, Jennings L, Berger R. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia: a cause for obscure massive gastrointestinal bleeding. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:E17-E19. |

| 52. | Jones DR, Hoffman J, Downie R, Haqqani M. Massive gastrointestinal haemorrhage associated with ileal lymphoid hyperplasia in Gaucher’s disease. Postgrad Med J. 1991;67:479-481. |

| 53. | Freiman JS, Gallagher ND. Mesenteric node enlargement as a cause of intestinal variceal hemorrhage in nodular lymphoid hyperplasia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1985;7:422-424. |

| 54. | Ersoy E, Gündoğdu H, Uğraş NS, Aktimur R. A case of diffuse nodular lymphoid hyperplasia. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2008;19:268-270. |

| 55. | Bharadhwaj G, Triadafilopoulos G. Endoscopic appearances of colonic lymphoid nodules: new faces of an old histopathological entity. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:946-950. |

| 56. | Smith MB, Blackstone MO. Colonic lymphoid nodules: another cause of the red ring sign. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:206-208. |

| 57. | Straub RF, Wilcox CM, Schwartz DA. Variable endoscopic appearance of colonic lymphoid tissue. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1994;19:158-64; discussion 164-5. |

| 58. | Molaei M, Kaboli A, Fathi AM, Mashayekhi R, Pejhan S, Zali MR. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia in common variable immunodeficiency syndrome mimicking familial adenomatous polyposis on endoscopy. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52:530-533. |

| 59. | Bayraktar Y, Ersoy O, Sokmensuer C. The findings of capsule endoscopy in patients with common variable immunodeficiency syndrome. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:1034-1037. |

| 60. | Shiff AD, Sheahan DG, Schwartz SS. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia in a defunctionalized colon. Gastrointest Endosc. 1973;19:144-145. |

| 61. | Leonidas JC, Krasna IH, Strauss L, Becker JM, Schneider KM. Roentgen appearance of the excluded colon after colostomy for infantile Hirschsprung’s disease. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1971;112:116-122. |

| 62. | Tomita S, Kojima M, Imura J, Ueda Y, Koitabashi A, Suzuki Y, Nakamura Y, Mitani K, Terano A, Fujimori T. Diffuse nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of the large bowel without hypogammaglobulinemia or malabsorption syndrome: a case report and literature review. Int J Surg Pathol. 2002;10:297-302. |

| 63. | Ruskoné-Fourmestraux A, Delmer A, Lavergne A, Molina T, Brousse N, Audouin J, Rambaud JC. Multiple lymphomatous polyposis of the gastrointestinal tract: prospective clinicopathologic study of 31 cases. Groupe D’étude des Lymphomes Digestifs. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:7-16. |

| 64. | Yatabe Y, Nakamura S, Nakamura T, Seto M, Ogura M, Kimura M, Kuhara H, Kobayashi T, Taniwaki M, Morishima Y. Multiple polypoid lesions of primary mucosa-associated lymphoid-tissue lymphoma of colon. Histopathology. 1998;32:116-125. |

| 65. | Yoshino T, Miyake K, Ichimura K, Mannami T, Ohara N, Hamazaki S, Akagi T. Increased incidence of follicular lymphoma in the duodenum. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:688-693. |

| 66. | Jeon JY, Lim SG, Kim JH, Lee KM, Cho SR, Han JH. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of the stomach in a patient with multiple submucosal tumors. Blood Res. 2013;48:287-291. |

| 67. | Ament ME, Rubin CE. Relation of giardiasis to abnormal intestinal structure and function in gastrointestinal immunodeficiency syndromes. Gastroenterology. 1972;62:216-226. |

| 68. | Ryan JC. Premalignant conditions of the small intestine. Semin Gastrointest Dis. 1996;7:88-93. |

| 69. | Castellano G, Moreno D, Galvao O, Ballestín C, Colina F, Mollejo M, Morillas JD, Solís Herruzo JA. Malignant lymphoma of jejunum with common variable hypogammaglobulinemia and diffuse nodular hyperplasia of the small intestine. A case study and literature review. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;15:128-135. |

| 70. | Harris M, Blewitt RW, Davies VJ, Steward WP. High-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma complicating polypoid nodular lymphoid hyperplasia and multiple lymphomatous polyposis of the intestine. Histopathology. 1989;15:339-350. |

| 71. | Kahn LB, Novis BH. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of the small bowel associated with primary small bowel reticulum cell lymphoma. Cancer. 1974;33:837-844. |

| 72. | Lamers CB, Wagener T, Assmann KJ, van Tongeren JH. Jejunal lymphoma in a patient with primary adult-onset hypogammaglobulinemia and nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of the small intestine. Dig Dis Sci. 1980;25:553-557. |

| 73. | Aguilar FP, Alfonso V, Rivas S, López Aldeguer J, Portilla J, Berenguer J. Jejunal malignant lymphoma in a patient with adult-onset hypo-gamma-globulinemia and nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of the small bowel. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:472-475. |

| 74. | Gonzalez-Vitale JC, Gomez LG, Goldblum RM, Goldman AS, Patterson M. Immunoblastic lymphoma of small intestine complicating late-onset immunodeficiency. Cancer. 1982;49:445-449. |

| 75. | Durham JC, Stephens DS, Rimland D, Nassar VH, Spira TJ. Common variable hypogammaglobulinemia complicated by an unusual T-suppressor/cytotoxic cell lymphoma. Cancer. 1987;59:271-276. |

| 76. | Matuchansky C, Morichau-Beauchant M, Touchard G, Lenormand Y, Bloch P, Tanzer J, Alcalay D, Babin P. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of the small bowel associated with primary jejunal malignant lymphoma. Evidence favoring a cytogenetic relationship. Gastroenterology. 1980;78:1587-1592. |

| 77. | Schaefer PS, Friedman AC. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of the small intestine with Burkitt’s lymphoma and dysgammaglobulinemia. Gastrointest Radiol. 1981;6:325-328. |

| 78. | Jonsson OT, Birgisson S, Reykdal S. Resolution of nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of the gastrointestinal tract following chemotherapy for extraintestinal lymphoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:2463-2465. |