Published online Dec 16, 2013. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v5.i12.605

Revised: November 20, 2013

Accepted: December 9, 2013

Published online: December 16, 2013

Processing time: 57 Days and 22.2 Hours

A gastric neuroendocrine tumor (NET) is generated from deep within the tissue mucosal layers. In many cases, NETs are discovered as submucosal tumor (SMT)-like structures by forming a tumor mass. This case has a clear mucosal demarcation line and developed like a polyp. A dilated blood vessel was found on the surface. The mass lacked the yellow color characteristic of NETs, and a SMT-like form was evident. Therefore, a nonspecific epithelial lesion was suspected and we performed endoscopy with magnifying narrow-band imaging (M-NBI). However, this approach did not lead to the diagnosis, as we diagnosed the lesion as a NET by biopsy examination. The lesion was excised by endoscopic submucosal dissection. The histopathological examination proved that the lesion was a polypoid lesion although it was also a NET because the tumor cells extended upward through the normal gland ducts scatteredly. To our knowledge, there is no previous report of NET G1 with such unique histopathological growth progress and macroscopic appearance shown by detailed examination using endoscopy with M-NBI.

Core tip: Neuroendocrine tumors which infiltrate into the mucosa may develop a polypoid appearance mimicking a primary epithelial process.

- Citation: Hirai M, Matsumoto K, Ueyama H, Fukushima H, Murakami T, Sasaki H, Nagahara A, Yao T, Watanabe S. A case of neuroendocrine tumor G1 with unique histopathological growth progress. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2013; 5(12): 605-609

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v5/i12/605.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v5.i12.605

Gastric neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are relatively rare lesions representing approximately 7% of all neuroendocrine tumors and less than 1% of all stomach neoplasms[1]. Most gastric NETs are found incidentally during upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy[2-6]. Gastric NETs usually have the endoscopic appearance of a submucosal tumor because they grow from deep within the mucosal layers and the tumor mass is yellow. The yellow submucosal tumor (SMT) can be detected by white light and the dilated blood vessel on the surface, which is considered to be a secondary change. Gastric NETs comprise 7% of all gastrointestinal NETs and 2% of all excised gastric polyps[7,8]. Randi et al[9] classified gastric NETs into three subtypes. Type I NETs typically arise from enterochromaffin-like cell (ECL) hyperplasia, which is stimulated by hypergastrinemia on a background of atrophic gastritis, especially type A gastritis. Type II lesions are associated with gastrinomas resulting in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES). Type III lesions are a sporadic disease associated with normal gastrin levels. In type I and II diseases, several polyps are often seen in clusters. However, type III lesions are usually solitary. The surrounding mucosa may be macroscopically normal, especially in type III lesions. Additionally, there may be evidence of atrophy (type I) or associated peptic ulcer (type II). Here, we report a case of a type I gastric NET without submucosal tumor shape that extended through the normal gland ducts and developed with polypoid growth.

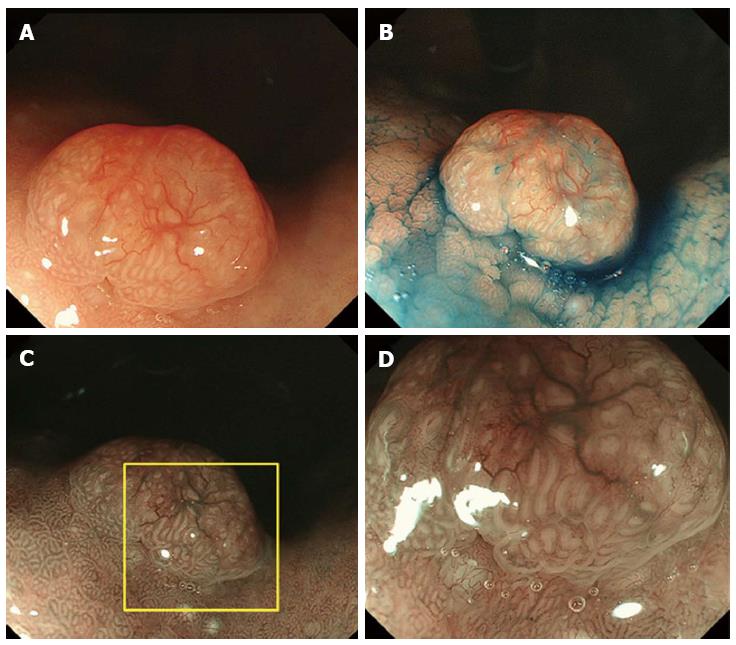

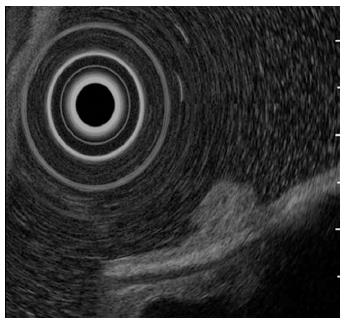

A 61-year-old man presented to his primary care physician with the complaint of mild epigastralgia. An upper GI endoscopy revealed an 8-mm, well-demarcated, protruding lesion on the anterior wall of the stomach body. Therefore, the patient was referred to our hospital. The lesion did not have the reddened appearance of strong inflammation and erosion on the surface like a hyperplastic polyp. The surrounding mucosa was not atrophic. In addition, the lesion was solitary (Figure 1A, B), which contrasts fundic gland polyps that develop as multiple small polyps. Therefore, we performed an endoscopy with magnifying narrow-band imaging (M-NBI) for further evaluation. There were dilated vessels on the surface of the lesion, but there were neither irregular microvessel patterns nor irregular microsurface patterns that indicated neoplastic change under M-NBI (Figure 1C, D). However, the lesion was considered an epithelial neoplasm because the demarcation line was distinct. The pathological evaluation of the biopsy specimen showed the mass was a NET. Endoscopic ultrasonography showed a protruding lesion in the mucosal layer that did not affect the submucosal layer (Figure 2).

The laboratory tests revealed normal serum pepsinogen I and serotonin levels, but a markedly increased serum gastrin level (1400 pg/mL; normal range, < 170) and parietal cell antibody level (× 20; normal range, < × 9). The test for anti-Helicobacter pylori IgG was negative. Whole body imaging procedures (CT-scan and abdominal ultrasonography) did not reveal metastatic involvement of any other organ.

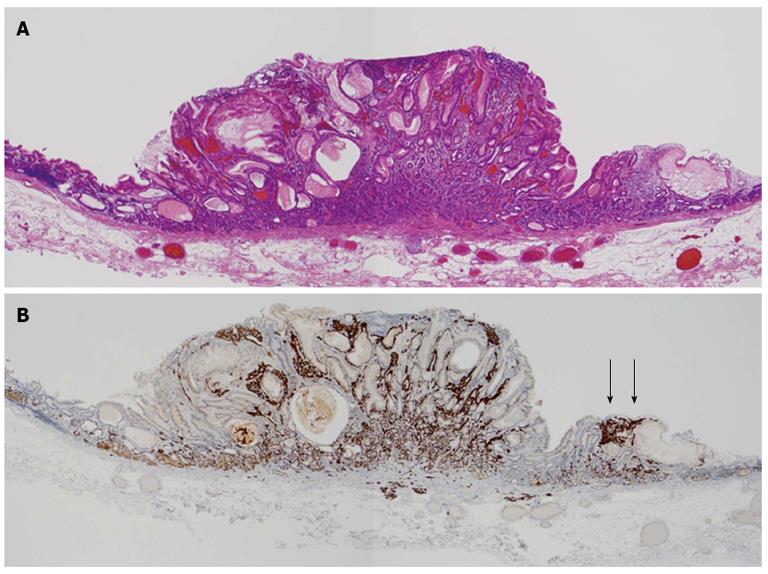

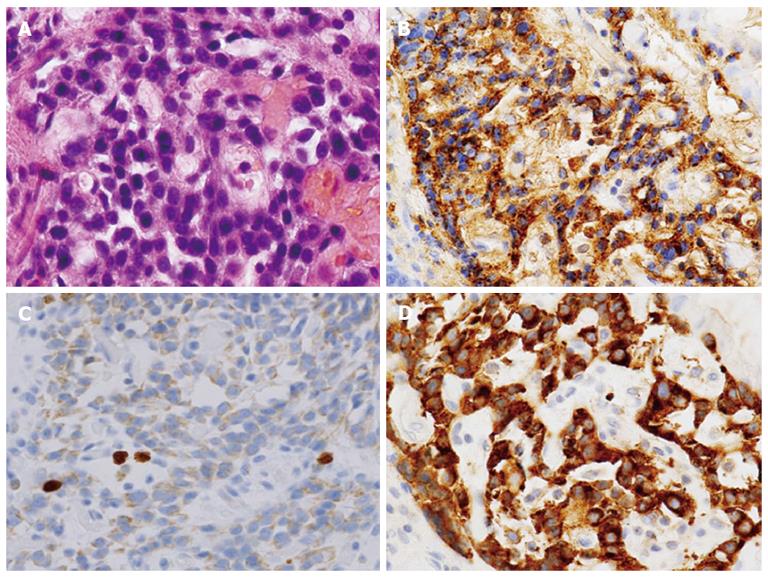

We determined the lesion was an atypical gastric NET and conducted endoscopic submucosal dissection. The histopathologic findings of the resected lesion led to the diagnosis of a neuroendocrine tumor of 8 mm × 9 mm. The tumor cells extended through the normal gland ducts scatteredly and infiltrated the submucosal and mucosal layers (Figure 3). Analysis by immunohistochemistry showed positivity for chromogranin A, synaptophysin, and CD56. The Ki-67 proliferation index was 1% (Figure 4). There were numerous ECL hyperplasias and micronests observed under the protruded lesion and in the normal mucosa around the lesion (Figure 3B, yellow arrow). According to the updated Sydney System, intestinal metaplasia was absent. Activity (granulocytic infiltration), inflammation (lymphocytic and mononuclear cell infiltration) and atrophy were moderate at the fornix mucosa and body of the stomach.

As a result of our analysis, we diagnosed the case as a type I neuroendocrine tumor G1 with a very atypical morphological and pathological growth that developed in the background of type A gastritis.

Type I NET is the most common lesion type and comprises approximately 70% to 80% of all gastric carcinoids[5,10-12]. According to the World Health Organization’s histological classification of gastrointestinal endocrine tumors, a well-differentiated endocrine tumor (synonymous with carcinoid) is defined as an epithelial tumor of usually monomorphous endocrine cells. These tumors have mild or no atypia, grow in the form of solid nests, trabeculae, or pseudoglandular tumors, and are restricted to the mucosa or submucosa[13]. Due to these features, most gastrointestinal NETs have the appearance of submucosal tumors and are visibly yellow by endoscopic examination. However, in the present case, the tumor extended through the normal gland duct scatteredly and did not present a submucosal tumor shape. The result was a well-demarcated polypoid growth presenting like an epithelial neoplasm by endoscopy. The lesion was not yellow and did not present as a tumor except for the mass. Moreover, the lesion did not have the appearance of a hyperplastic polyp and fundic gland polyp.

The percentage of gastric carcinoids amongst all gastric malignancies has increased from 0.3% to 1.77% since the 1950s. The proportion of gastric carcinoids among all gastrointestinal carcinoids has increased from 2.4% to 8.7%[7]. One reason for the increased detection rate is undoubtedly increased awareness of these lesions among pathologists and endoscopists. Additionally, the widespread use of endoscopy and biopsies and the application of immunohistochemical methods have increased detection rates[14]. The increased detection rate has been accompanied by the detection of morphologically and histopathologically untypical lesions. In this report, we present a gastric NET with the unique histopathological growth progress. The lesion did not present as a submucosal tumor but mimicked the endoscopic appearance of epithelial neoplasms.

In the present case, diagnosis by the endoscopic appearance under white light and M-NBI was very difficult. We could not reach a diagnosis until the histopathologic findings of the excised lesion were available. Current methods using M-NBI for the diagnosis of lesions with the endoscopic appearance of typical differentiated adenocarcinoma have been developed and established, especially for the diagnosis of well differentiated adenocarcioma. However, lesions that are confusing and cannot be diagnosed only by endoscopic appearance have been discovered repeatedly. In these cases, biopsies remain necessary. The present case was one such case.

To our knowledge, a NET G1 showing such a macroscopic appearance and histopathological growth progress has not been reported previously. We believe that this is the first report of a NET G1 with such unique histopathological growth progress, including an examination the pathological findings of the excised lesion and the endoscopic appearance under magnifying NBI in detail.

A 61-year-old man with the complaint of mild epigastralgia.

An 8-mm, solitary, well-demarcated, protruding lesion was observed on the anterior wall of the stomach body.

Fundic gland polyp, hyperplastic polyp, adenocarcinoma.

A markedly increased serum gastrin level (1400 pg/mL; normal range, < 170) and parietal cell antibody level (× 20; normal range, < × 9); other laboratory tests were within the normal limits.

Endoscopic ultrasonography showed a protruding lesion in the mucosal layer that did not affect the submucosal layer.

The biopsy specimen showed the mass was not an epithelial tumor but a neuroendocrine tumors (NETs).

The tumor was resected by endoscopic submucosal dissection.

NETs sometimes lack submucosal tumor-like form and mimic epithelial neoplasms if the tumor cells extended through the normal gland ducts scatteredly.

NETs which infiltrate into the mucosa may develop a polypoid appearance mimicking a primary epithelial process.

P- Reviewers: Deutsch JC, Rehman HU S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Nikou GC, Angelopoulos TP. Current concepts on gastric carcinoid tumors. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:287825. |

| 2. | Modlin IM, Oberg K, Chung DC, Jensen RT, de Herder WW, Thakker RV, Caplin M, Delle Fave G, Kaltsas GA, Krenning EP. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:61-72. |

| 3. | Soga J. Early-stage carcinoids of the gastrointestinal tract: an analysis of 1914 reported cases. Cancer. 2005;103:1587-1595. |

| 4. | Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003;97:934-959. |

| 5. | Borch K, Ahrén B, Ahlman H, Falkmer S, Granérus G, Grimelius L. Gastric carcinoids: biologic behavior and prognosis after differentiated treatment in relation to type. Ann Surg. 2005;242:64-73. |

| 6. | La Rosa S, Inzani F, Vanoli A, Klersy C, Dainese L, Rindi G, Capella C, Bordi C, Solcia E. Histologic characterization and improved prognostic evaluation of 209 gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms. Hum Pathol. 2011;42:1373-1384. |

| 7. | Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 50-year analysis of 562 gastric carcinoids: small tumor or larger problem? Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:23-32. |

| 8. | Gencosmanoglu R, Sen-Oran E, Kurtkaya-Yapicier O, Avsar E, Sav A, Tozun N. Gastric polypoid lesions: analysis of 150 endoscopic polypectomy specimens from 91 patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2236-2239. |

| 9. | Rindi G, Luinetti O, Cornaggia M, Capella C, Solcia E. Three subtypes of gastric argyrophil carcinoid and the gastric neuroendocrine carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:994-1006. |

| 10. | Zhang L, Ozao J, Warner R, Divino C. Review of the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of type I gastric carcinoid tumor. World J Surg. 2011;35:1879-1886. |

| 11. | Dakin GF, Warner RR, Pomp A, Salky B, Inabnet WB. Presentation, treatment, and outcome of type 1 gastric carcinoid tumors. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93:368-372. |

| 12. | Seya T, Shinji E, Tanaka N, Shinji S, Koizumi M, Horiba K, Ishikawa N, Yokoi K, Ohaki Y, Tajiri T. A case of multiple gastric carcinoids that could not be preoperatively diagnosed. J Nippon Med Sch. 2007;74:430-433. |

| 13. | Solcia E, Kloppel G, Sobin LH. Histological Typing of Endocrine Tumors. International Histological Classification of Tumors. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer 2013; . |

| 14. | Modlin IM, Kidd M, Latich I, Zikusoka MN, Shapiro MD. Current status of gastrointestinal carcinoids. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1717-1751. |