Published online Jun 16, 2012. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v4.i6.241

Revised: February 23, 2012

Accepted: May 27, 2012

Published online: June 16, 2012

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) has a significant complication rate which can be lowered by adopting technical variations of proven beneficial effect and prophylactic maneuvers such as pancreatic stenting during ERCP or periprocedural non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug administration. However, adoption of these prophylactic maneuvers by endoscopists is not uniform. In this editorial we discuss the beneficial effects of the aforementioned maneuvers.

- Citation: Vila JJ, Artifon EL, Otoch JP. Post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography complications: How can they be avoided? World J Gastrointest Endosc 2012; 4(6): 241-246

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v4/i6/241.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v4.i6.241

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is an endoscopic procedure which has a high complication rate ranging from 5%-40% in different series depending on the difficulty of the examination, previous diagnosis and patient comorbidities. These complications develop mainly as a consequence of papillary maneuvers to achieve deep biliary or pancreatic duct cannulation.

Nowadays, ERCP has entered a new era in which related procedures only fit therapeutic intention. It is not ethically justified to offer such risky exploration to patients intended only as a diagnostic procedure. Thus, patients may be exposed to these risks when the intention of the procedure is to offer a minimally invasive exam with excellent results, thus avoiding surgery or radiologic interventions.

However, in recent years this morbidity has declined due to the benefits of different maneuvers which have allowed this technique to be performed with greater security. This article presents and discusses factors which can help to reduce the morbidity of ERCP, including both non-technical factors, and therefore, endoscopist-independent, and technical factors, and therefore, endoscopist-dependent. In the latter we will include the role of the different cannulation techniques and their influence on post-ERCP morbidity. With regard to non-technical factors, we will review the role of two methods which have accumulated scientific evidence in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis such as pancreatic stent placement and administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

We consider endoscopist-independent prophylactic factors as those factors which have proven prophylactic benefit, such as pancreatic stent placement and administration of NSAIDs and antibiotics. The first two factors are used in the prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis and the latter in the prophylaxis of post-ERCP cholangitis and other infectious complications.

Pancreatic stent placement in various studies was proved to be effective in preventing the development of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Several meta-analyses have also been published, the first in 2004 which included 5 studies and 481 patients[1]. This meta-analysis showed that the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis was significantly lower in the stented group (5.8%) versus the control group (15.5%), with an odds ratio (OR) of 3.2 and the number of patients needed to treat (NNT) to prevent pancreatitis was 10. A subsequent meta-analysis included a sixth randomized controlled trial, with similar results[2]. In the stented group the incidence of acute pancreatitis was 12% vs 24% in the control group, with a protective OR of 0.44 for the stented group and a NNT of only 8. The final meta-analysis was published recently and included 8 randomized controlled trials which demonstrated a reduction in the OR to 0.22 (95% CI: 0.12-0.38, P < 0.01) in the stented group and a NNT of 8 patients[3].

These results have not gone unnoticed in scientific societies, and the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy includes the recommendation to place prophylactic pancreatic stents in high-risk patients undergoing ERCP[4]. This group of high-risk patients is not well defined, although there is a consensus to consider the following high-risk patients: patients undergoing ERCP for sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, young women, patients with previous history of pancreatitis, patients in whom a high number of pancreatic duct cannulations and injections have been made during cannulation or ampullectomy, and many authors advocate the introduction of a prophylactic pancreatic stent when using the double-wire technique.

The recommended stent is currently a short (≤ 5 cm) 5F plastic stent, and preferably with only an external flange, although some authors prefer to introduce double flanged stents[5,6]. Up to 10 d after stenting, observations for spontaneous migration should be made and if present, the stent should be endoscopically extracted.

However, it is not always easy to insert a pancreatic stent and complications related to pancreatic duct cannulation to insert the stent can occur. Therefore, prophylactic pancreatic stenting is recommended when the endoscopist’s success rate for this maneuver is higher than 75%[4].

Currently, there are four prospective studies evaluating the utility of prophylactic administration of NSAIDs for post-ERCP pancreatitis, which have been evaluated in three meta-analyses[7-9]. These data have shown that the rectal administration of 100 mg of diclofenac immediately after ERCP, or 100 mg of indomethacin immediately prior to ERCP, significantly decrease the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis from 12.5% to 4.4%, with a risk reduction of 0.33 and an NNT of 15 patients. Furthermore, in published studies no adverse effects attributable to NSAIDs have been described.

The use of NSAIDs peri-ERCP is indicated in low-risk cases to prevent the development of post-ERCP pancreatitis[4] and probably, although this has not been assessed, in patients at high risk in whom a prophylactic pancreatic stent could not be inserted.

The prophylactic use of antibiotics before or after ERCP to prevent the development of post-ERCP cholangitis or other infectious complications has been extensively evaluated in numerous studies. The British Society of Gastroenterology guide for antibiotic prophylaxis in gastrointestinal endoscopy has recently been published and recommends the prophylactic administration of antibiotics during ERCP in patients who are in the following situations: patients who are not expected to obtain full patency of the bile duct by one ERCP, patients with advanced hematologic cancer, patients with a history of liver transplantation, patients with pancreatic pseudocysts and patients with severe neutropenia[10].

Quinolones are the recommended antibiotics, although the antibiotic and regimen should be tailored to the antimicrobial resistance profile of each hospital.

Confirmation that the best predictor of the development of post-ERCP infectious complications is incomplete resolution of biliary obstruction was subsequently confirmed in a meta-analysis which included nine prospective randomized studies with a total of 1573 patients[11]. According to this meta-analysis, prophylactic antibiotic therapy halved the risk of bacteremia (RR: 050, 95% CI: 0.33-0.78) after ERCP, but did not show any effect on overall mortality (RR: 1.33, 95% CI: 0.32-5.44). In the subgroup of patients in whom ERCP completely resolved the biliary obstruction, the protective effect of antibiotics had no impact. In contrast, the subgroup of patients in whom biliary obstruction could not be resolved completely with ERCP benefitted from antibiotic prophylaxis.

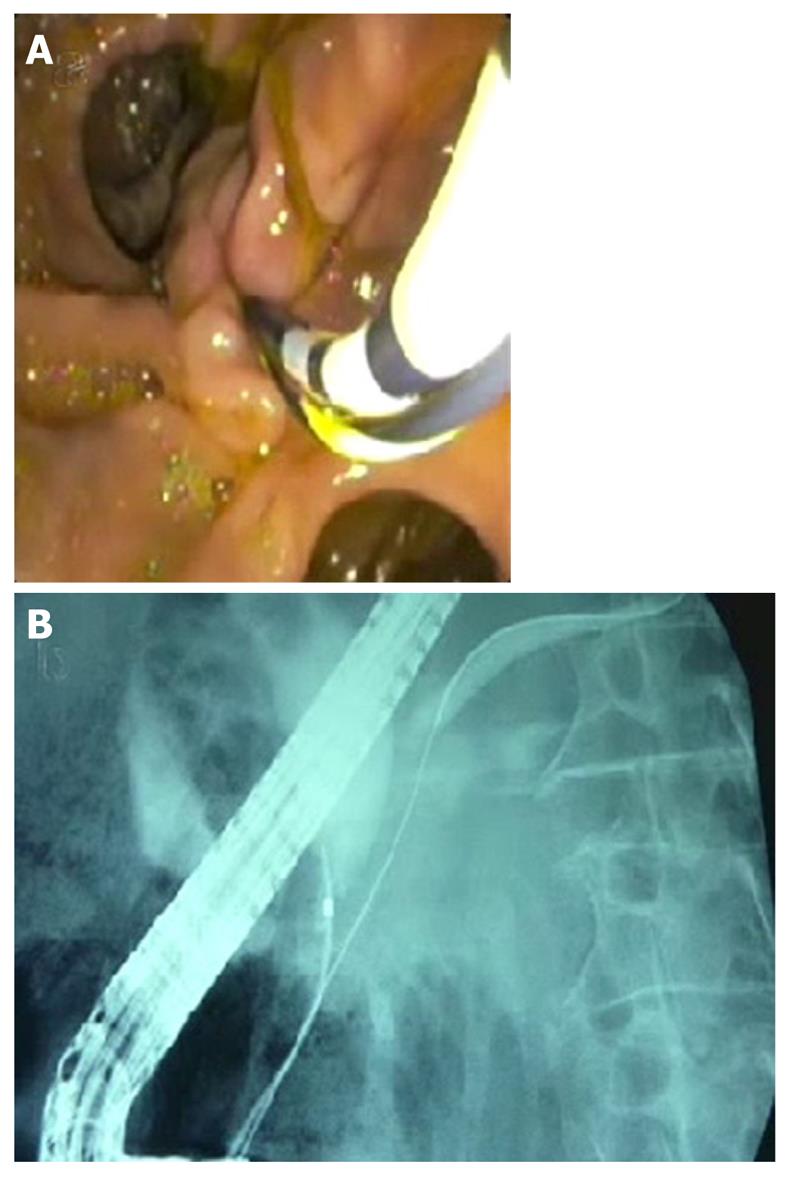

Of the endoscopist-dependent protective factors we can include all the described cannulation variations which have proved beneficial in the incidence of post-ERCP complications. The first factor is undoubtedly the guide-wire cannulation technique. This technique was introduced by Siegel and Pullano in 1987[12]. Cannulation with a guide-wire consists of the introduction of a guide-wire into the bile or pancreatic duct instead of contrast injection as the first maneuver. There are several variations of this technique, and the tip of the catheter or sphincterotome is inserted initially with which we will cannulate a few millimeters through the papillary orifice and then introduce the guide-wire to the target. Another variation is direct cannulation with the guide-wire hovering a few millimeters or even one or two inches through the catheter or sphincterotome. This latter option is especially useful in pancreatic cannulation through the minor papilla (Figure 1).

The benefit of this technique compared with classic contrast cannulation has been demonstrated in several studies which show similar results and have been jointly analyzed in a recent meta-analysis[13,14]. This meta-analysis included 5 studies and 1762 patients, and demonstrated that the use of the guide-wire technique significantly improved the primary cannulation rate from 74.9% to 85.3% (OR: 2.05, 95% CI: 1.27-3.31) and more importantly, significantly reduced the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis from 8.6% to 1.6% (OR: 0.23, 95% CI: 0.13-0.41). Consequently, the authors concluded that the guide-wire technique should be considered the standard cannulation technique.

The double-wire cannulation technique was first described by Dumonceau et al[15] in 1998. It can be used when access to the pancreatic duct can only be achieved during a biliary ERCP. A guide-wire is placed into the pancreatic duct and parallel to this guide-wire a catheter or sphincterotome is inserted to cannulate the bile duct (Figure 2). The functions and benefits attributed to this technique are that the guide-wire in the pancreatic duct could open a stenotic papillary orifice, stabilize the papilla, raise the papilla towards the working channel of the endoscope, rectify the pancreatic and common duct, drain the pancreatic duct and minimize the injections into the pancreatic duct.

One of the first studies evaluating this technique compared a group of 27 patients with difficult cannulation who underwent this technique with another group of 26 patients in whom the endoscopist persisted in trying the classical contrast injection technique. The double-wire technique significantly improved the rate of cannulation to 93% vs 58% achieved with the classic technique (P = 0.0085), showing no significant differences in the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis[16]. However, Ito et al[17] did not obtain such good results with this technique and described a cannulation rate of 73% with an incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis of 12%.

A randomized prospective trial comparing a group of 97 patients with difficult cannulation in whom the double-wire technique was used with another group of 91 patients in whom persistence of classical cannulation was attempted has been published recently[18]. The double-wire technique resulted in a poorer outcome compared with the classical technique regarding the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis (17% vs 8%, P > 0.05), and the cannulation rate was significantly worse with the double-wire technique (OR: 0.66, 95% CI: 0.64-1.12). The authors concluded that the double-wire technique offers no advantage over the classical technique in achieving biliary cannulation, and did not decrease the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis.

Therefore, the data available in the literature on this technique are contradictory and at present it is not recommended for achieving cannulation or decreasing post-ERCP pancreatitis. This technique may be useful for achieving biliary cannulation in patients in whom repeated pancreatic duct injections are performed. If this technique is used, a prophylactic pancreatic stent should also be inserted.

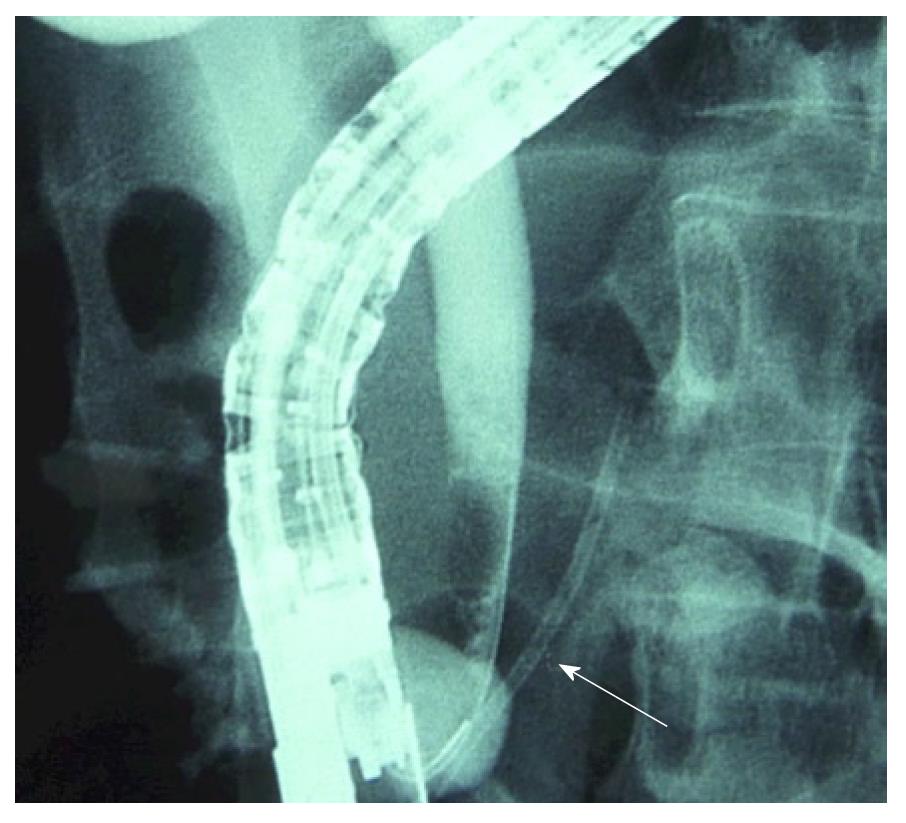

A variation of the previous technique is guide-wire cannulation over a pancreatic stent (Figure 3). This technique consists of the introduction of a pancreatic stent over the guide-wire initially left in the pancreatic duct, and in parallel with a sphincterotome or catheter to cannulate the bile duct. In a first study, Fogel et al[19] reported a significantly lower incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis in patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction in whom a pancreatic stent was placed followed by needle knife sphincterotomy compared with the double-wire technique (10.7% vs 28.3%, P < 0.05). In a similar group of patients Madacsy et al[20] also showed a significant benefit using a pancreatic stent and had no cases of post-ERCP pancreatitis compared with a post-ERCP incidence of 43% in the group of patients in whom the needle knife was performed with a guide-wire into the pancreatic duct (P < 0.05).

More recently, Ito et al[21] did not find significant differences using the cannulation over a pancreatic stent technique compared with the double-wire cannulation technique regarding primary cannulation (80% vs 94%, P = 0.15) in a group of patients with difficult cannulation, however, there was a significant benefit in the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis (2.9% vs 23%, P < 0.05).

Therefore, this technique offers a clear protective effect against the development of post-ERCP pancreatitis, and would be recommended when we have access to the pancreatic duct and needle knife sphincterotomy is decided.

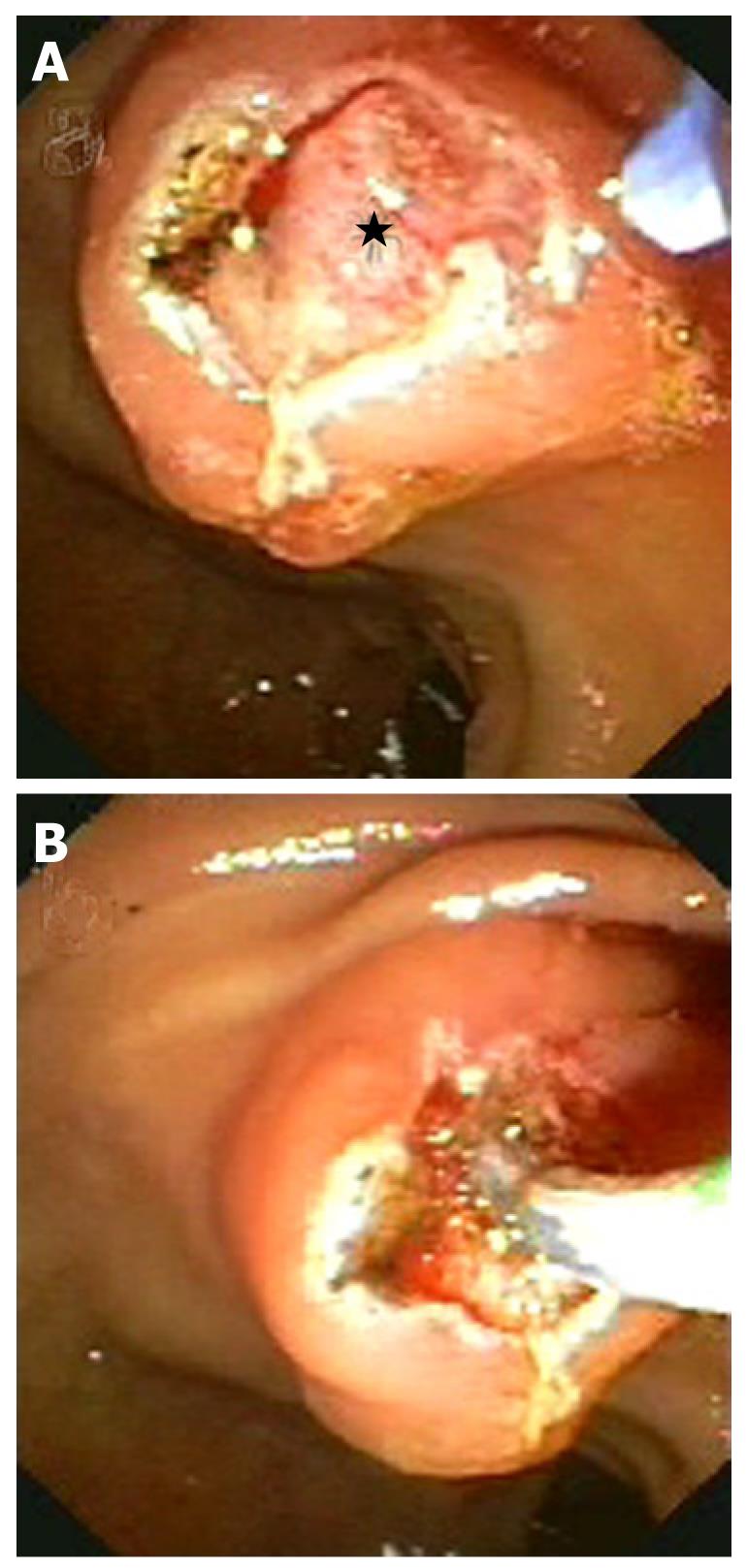

Finally, needle knife sphincterotomy (Figure 4) is a well known and validated technique which has different variants: cephalad incision from papillary orifice, pancreatic precut and fistulotomy. Although there are no studies comparing the outcomes of these variants, optimal results with the pancreatic precut technique and fistulotomy technique have been described recently.

The appropriate timing of this technique has been studied. In a recently published meta-analysis including 6 prospective, randomized, controlled trials comparing the rate of cannulation and the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis in a group of patients with difficult cannulation in whom early pre-cut was performed (442 patients) with another group in whom persistence in cannulation was performed with late pre-cut if cannulation was unsuccessful (524 patients)[22]. There were no differences in the success rate of cannulation (90.2% vs 89.6%, OR: 1.20, 95% CI: 0.54-2.69), however, significant differences were seen in the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis (2.48% vs 5.34%, OR: 0.47, (95% CI: 0.24-0.91) favoring early pre-cut.

Therefore, performing early pre-cut has a similar rate of primary cannulation but is associated with a lower incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis.

Other endoscopist-dependent factors no less important in our opinion when it comes to reducing the incidence of post-ERCP complications are subjective and difficult to evaluate. These include knowledge update, the progression to more complicated cases and techniques, and cautious attitude of the endoscopist. These factors are extremely important and help to identify not only an appropriate indication for ERCP, but also the different therapeutic techniques performed during this procedure, hopefully contributing to a reduction in the incidence of complications.

The acceptance of the aforementioned maneuvers by endoscopists is not uniform. An American survey showed that expert endoscopists are aware of the protective effect of pancreatic stents in patients at high risk, but the indications for stent placement and the type of stent chosen varies widely among endoscopists[23]. A recently published survey showed that up to 21.3% of endoscopists in Europe never perform prophylactic pancreatic stenting despite favorable scientific evidence, mainly because of lack of experience[24]. In this survey it was shown that the vast majority of endoscopists did not regularly attempt prophylactic pancreatic stenting when procedure-related risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis were present, and slightly more frequently when patient-related risk factors were present. Moreover, 83.7% of endoscopists do not use NSAIDS for post-ERCP pancreatitis prophylaxis[24].

Expert endoscopists with greater experience in ERCP are more reluctant to adopt changes to their usual technique, probably because they have favorable rates of outcomes and complications, and because they think that introducing an alternative technique into their working methods might lead to a temporary decrease in successful cannulation rates and an increase in complication rates. However, a recent study from Japan has shown that wire-guided cannulation is useful immediately after its introduction in a specialized center with expertise in contrast cannulation, and in this context wire-guided cannulation has a higher rate of primary cannulation, a shorter procedural time and a lower rate of hyperamylasemia[25]. On the other hand, endoscopists with less experience and those in training should know these techniques and adopt them as standard practice given the scientific evidence of benefit.

The question is whether an endoscopist’s personal preference is enough reason to maintain a technique? In our opinion it is not, since there is scientific evidence supporting a different policy. Endoscopists in training should adopt the technique proven to be the best. On the other hand, expert endoscopists who reject changes in their technique could argue that they already achieve favorable outcomes. But even good outcomes can be improved and expert ERCPists should be the first to adopt proven variations in technique to obtain clinical improvement.

To conclude, although recommendations in endoscopy should not be rigid and cannot replace clinical judgment[4], it is the duty of both expert and non-expert endoscopists to know their results and complication rates and if these are unfavorable, evaluate which of the previously described variations should be performed to improve their outcomes.

Peer reviewer: Ka Ho Lok, MBChB, MRCP, FHKCP, FHKAM, Associate Consultant, Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Tuen Mun Hospital, Tsing Chung Koon Road, Tuen Mun, Hong Kong, China

S- Editor Yang XC L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Yang XC

| 1. | Singh P, Das A, Isenberg G, Wong RC, Sivak MV, Agrawal D, Chak A. Does prophylactic pancreatic stent placement reduce the risk of post-ERCP acute pancreatitis? A meta-analysis of controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:544-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Andriulli A, Forlano R, Napolitano G, Conoscitore P, Caruso N, Pilotto A, Di Sebastiano PL, Leandro G. Pancreatic duct stents in the prophylaxis of pancreatic damage after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a systematic analysis of benefits and associated risks. Digestion. 2007;75:156-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Choudhary A, Bechtold ML, Arif M, Szary NM, Puli SR, Othman MO, Pais WP, Antillon MR, Roy PK. Pancreatic stents for prophylaxis against post-ERCP pancreatitis: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:275-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Dumonceau JM, Andriulli A, Deviere J, Mariani A, Rigaux J, Baron TH, Testoni PA. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline: prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2010;42:503-515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zolotarevsky E, Fehmi SM, Anderson MA, Schoenfeld PS, Elmunzer BJ, Kwon RS, Piraka CR, Wamsteker EJ, Scheiman JM, Korsnes SJ. Prophylactic 5-Fr pancreatic duct stents are superior to 3-Fr stents: a randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy. 2011;43:325-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chahal P, Tarnasky PR, Petersen BT, Topazian MD, Levy MJ, Gostout CJ, Baron TH. Short 5Fr vs long 3Fr pancreatic stents in patients at risk for post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:834-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dai HF, Wang XW, Zhao K. Role of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2009;8:11-16. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Zheng MH, Xia HH, Chen YP. Rectal administration of NSAIDs in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a complementary meta-analysis. Gut. 2008;57:1632-1633. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Elmunzer BJ, Waljee AK, Elta GH, Taylor JR, Fehmi SM, Higgins PD. A meta-analysis of rectal NSAIDs in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Gut. 2008;57:1262-1267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Allison MC, Sandoe JA, Tighe R, Simpson IA, Hall RJ, Elliott TS. Antibiotic prophylaxis in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gut. 2009;58:869-880. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Brand M, Bizos D, O'Farrell P. Antibiotic prophylaxis for patients undergoing elective endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;CD007345. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Siegel JH, Pullano W. Two new methods for selective bile duct cannulation and sphincterotomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1987;33:438-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cennamo V, Fuccio L, Zagari RM, Eusebi LH, Ceroni L, Laterza L, Fabbri C, Bazzoli F. Can a wire-guided cannulation technique increase bile duct cannulation rate and prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis?: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2343-2350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Artifon EL, Sakai P, Cunha JE, Halwan B, Ishioka S, Kumar A. Guidewire cannulation reduces risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis and facilitates bile duct cannulation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2147-2153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Dumonceau JM, Devière J, Cremer M. A new method of achieving deep cannulation of the common bile duct during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Endoscopy. 1998;30:S80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Maeda S, Hayashi H, Hosokawa O, Dohden K, Hattori M, Morita M, Kidani E, Ibe N, Tatsumi S. Prospective randomized pilot trial of selective biliary cannulation using pancreatic guide-wire placement. Endoscopy. 2003;35:721-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ito K, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Obana T, Horaguchi J, Takasawa O, Koshita S, Kanno Y. Pancreatic guidewire placement for achieving selective biliary cannulation during endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:5595-600; discussion 5599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Herreros de Tejada A, Calleja JL, Díaz G, Pertejo V, Espinel J, Cacho G, Jiménez J, Millán I, García F, Abreu L. Double-guidewire technique for difficult bile duct cannulation: a multicenter randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:700-709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fogel EL, Eversman D, Jamidar P, Sherman S, Lehman GA. Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction: pancreaticobiliary sphincterotomy with pancreatic stent placement has a lower rate of pancreatitis than biliary sphincterotomy alone. Endoscopy. 2002;34:280-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Madácsy L, Kurucsai G, Fejes R, Székely A, Székely I. Prophylactic pancreas stenting followed by needle-knife fistulotomy in patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction and difficult cannulation: new method to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis. Dig Endosc. 2009;21:8-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ito K, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Obana T, Horaguchi J, Takasawa O, Koshita S, Kanno Y, Ogawa T. Can pancreatic duct stenting prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis in patients who undergo pancreatic duct guidewire placement for achieving selective biliary cannulation? A prospective randomized controlled trial. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1183-1191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cennamo V, Fuccio L, Zagari RM, Eusebi LH, Ceroni L, Laterza L, Fabbri C, Bazzoli F. Can early precut implementation reduce endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-related complication risk? Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Endoscopy. 2010;42:381-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Brackbill S, Young S, Schoenfeld P, Elta G. A survey of physician practices on prophylactic pancreatic stents. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:45-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Dumonceau JM, Rigaux J, Kahaleh M, Gomez CM, Vandermeeren A, Devière J. Prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a practice survey. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:934-99, 934-99. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Nakai Y, Isayama H, Tsujino T, Sasahira N, Hirano K, Kogure H, Sasaki T, Kawakubo K, Yagioka H, Yashima Y. Impact of introduction of wire-guided cannulation in therapeutic biliary endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:1552-1558. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |