Published online May 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i5.105031

Revised: March 31, 2025

Accepted: April 24, 2025

Published online: May 16, 2025

Processing time: 123 Days and 6.3 Hours

Although the majority of gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopies in the United States are now performed with propofol sedation, a substantial minority are performed with midazolam and fentanyl sedation. Despite the ubiquity of conscious sedation with midazolam and fentanyl in the United States, there is scant evidence specifically supporting the superiority of midazolam plus fentanyl over single agent mida

To investigate whether sedation with midazolam alone is noninferior to sedation with midazolam plus fentanyl in GI endoscopy.

We conducted a randomized, single-blind study to compare the safety and effectiveness of single agent midazolam vs. standard fentanyl/midazolam moderate sedation in 300 outpatients presenting for upper endoscopy and/or colonoscopy at a tertiary care hospital. Primary outcomes were patient satisfaction as measured by the previously validated Procedural Sedation Assessment Survey. Secondary outcomes were procedure quality measures and adverse events. Statistical ana

There was no difference in patient satisfaction between sedation groups, as measured by a less than 1 point difference between groups in Procedural Sedation Assessment Survey scores for discomfort during the procedure, and for preference for level of sedation with future procedures. There were no differences in adverse events or procedure quality measures. Cecal intubation time was 1 minute longer in the single agent midazolam group, and an average of 2.7 mg more midazolam was administered when fentanyl was not included in the sedation regimen. The recruitment goal of 772 patients was not reached.

It may be possible to minimize or avoid using fentanyl in endoscopist administered moderate sedation for GI endoscopy. We hope these findings spur further work in this under-researched area.

Core Tip: Despite the ubiquity of conscious sedation with midazolam and fentanyl in gastrointestinal endoscopy in the United States, there is scant evidence supporting the superiority of midazolam plus fentanyl over single agent midazolam sedation in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Our results suggest that sedation with midazolam alone may be noninferior to midazolam plus fentanyl with regard to patient satisfaction, adverse events, and procedure quality. However, the recruitment goal was not reached. These findings should spur further research in this under investigated area.

- Citation: Cohen GS, Kim KYA. Fentanyl may not be necessary for adequate endoscopic moderate sedation. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(5): 105031

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i5/105031.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i5.105031

In the United States, while there are no current data, most gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopic procedures are now performed with propofol sedation administered by an anesthesia professional[1]. However, endoscopist administered moderate sedation for upper endoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy is still used in a substantial proportion of cases, and is over

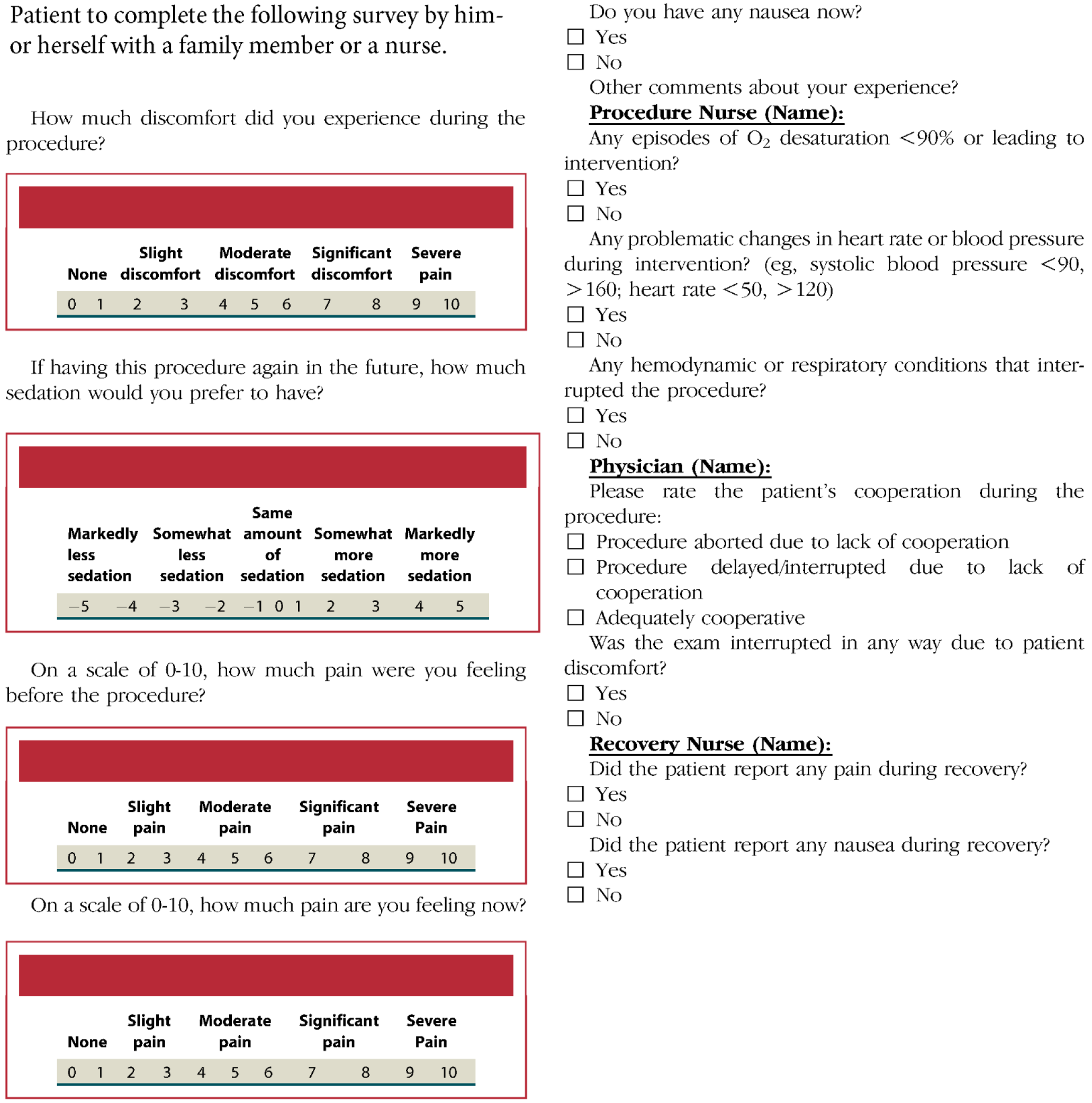

Between April 2021 and November 2022, we enrolled English-speaking outpatients over age 18 presenting for EGD and/or colonoscopy (clinicaltrials.gov NCT04807101). The protocol was approved by the Northwestern University institutional review board. Patients were excluded if, according to their medical history in the electronic medical record or per their verbal report, they had an allergy or prior adverse event to either fentanyl or midazolam or if they had previously not tolerated endoscopy with moderate sedation and required monitored anesthesia care. Upper endoscopies were performed with Olympus EVIS EXERA II GIF-Q180 upper endoscopes. Colonoscopies were performed with Olympus EVIS EXERA II CF-Q180AL/I colonoscopes. Patients were blinded to the sedation medications assigned by the randomization tool, but the endoscopist was not. The randomization tool used simple randomization to assign each participant to a sedation group. Midazolam was administered intravenously as 1-3 mg doses at least 2 minutes apart. Fentanyl was administered intravenously as 25 mcg doses at least 2 minutes apart. If sedation was felt to be inadequate, based on the clinical judgement of the endoscopist, the endoscopist was allowed to break protocol by administering fentanyl to patients assigned to sedation with midazolam alone. The endoscopist (author Greg S Cohen) had 16 years of experience post training. Sedation was targeted to moderate sedation (conscious sedation) as defined by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA)[6]. To measure patient satisfaction with sedation we used the previously validated Procedural Sedation Assessment Survey (PROSAS)[7] shown in Figure 1. The primary outcomes were patient satisfaction with sedation as gauged by the first 2 PROSAS questions using visual analog scales to rate on a scale of 0 to 10 the patient’s level of discomfort during the procedure, and to rate on a scale of -5 to 5 the patient’s preference to receive less or more sedation for future procedures. Secondary outcomes consisted of quality measures including preparation quality, cecal intubation rate/time, colonoscopy withdrawal time, adenoma detection rates, sessile serrated polyp detection rates, and adverse events. Power calculation based on noninferiority test with 80% power to detect an equivalence within 10% (i.e., a 1 point difference on the PROSAS visual analog scales) with 95% confidence intervals, showed that 772 participants were needed.

Recruitment was incomplete at 300 participants who were recruited by a single endoscopist. All procedures were performed on low risk outpatients with ASA classification I or II[6]. Interventions performed during procedures were limited to cold biopsies and hot and cold snare polypectomies. There were no advanced interventions performed including variceal band ligation, stent placement, or endoscopic submucosal dissection. In the midazolam only group, there were 15 upper endoscopies and 122 colonoscopies performed on 148 patients. In the midazolam plus fentanyl group, there were 17 upper endoscopies and 119 colonoscopies performed on 152 patients. There were no differences in procedure or patient numbers between groups.

There was no difference in age or gender between groups. There was no difference in patient satisfaction between sedation groups, as measured by a less than 1 point difference between groups in PROSAS scores for discomfort during the procedure, and for preference for level of sedation with future procedures. As shown in Table 1, there were no differences in adverse events or procedure quality measures including preparation quality, cecal intubation rate, withdrawal time, adenoma detection rate, and sessile serrated polyp detection rate. EGD procedure times were not recorded. There were no differences in pain or nausea during recovery. One subject in each group reported nausea during recovery, and no subjects reported pain during recovery. Cecal intubation time was 1 minute longer in the single agent midazolam group. In the midazolam only group the mean (SD) dose of midazolam was 11.3 mg (3.8 mg). In the midazolam plus fentanyl group the mean (SD) dose of midazolam was 8.6 mg (3.1 mg), P < 0.001 compared to the midazolam only group. An average of 2.7 mg more midazolam was administered when fentanyl was not included in the sedation regimen. In the midazolam plus fentanyl group the mean (SD) dose of fentanyl was 74 mcg (21 mcg). There were 2 instances of breaking protocol to give fentanyl to subjects in the midazolam only arm. For one subject having an EGD, 100 mcg fentanyl was given off protocol due to agitation, but the procedure was still aborted due to lack of cooperation and agitation with the scope at the cricopharyngeus. For the other subject who had an EGD followed by colonoscopy, pain during the colonoscopy was addressed by giving 50 mcg fentanyl around the same time a loop was reduced. After that the subject was comfortable for the rest of the exam.

| Characteristics | Midazolam | Midazolam/fentanyl | P value (or 95%CI) |

| n | 148 | 152 | - |

| Age (year), SD | 52.3 (10.4) | 52.3 (11.1) | 1a |

| Male | 59% | 53% | 0.3a |

| Upper endoscopy (EGD) (n) | 15 | 17 | 0.9a |

| Colonoscopy (n) | 122 | 119 | 0.4a |

| EGD/colonoscopy (n) | 11 | 16 | 0.5a |

| Adverse events (n) | 2d | 1d | 0.6b |

| Nausea (n) | 1 | 1 | 1b |

| PROSAS discomfort score on a scale of 0 to 10, SD | 0.30 (1.1) | 0.29 (1.2) | (-0.24 to 0.27)c |

| PROSAS future sedation preference score on a scale of -5 to 5, SD | -0.09 (0.78) | -0.28 (0.94) | (0-0.39)c |

| Prep quality, Boston Bowel Prep score, SD | 8.9 (0.64) | 8.9 (0.39) | 0.3a |

| Cecal intubation rate | 100% | 100% | 1a |

| Cecal intubation time (minute), SD | 7.99 (3.66) | 6.97 (3.10) | 0.02a |

| Withdrawal time (minute), SD | 16.29 (4.34) | 16.44 (4.01) | 0.8a |

| Adenoma detection | 36.7% | 38.3% | 1a |

| Sessile serrated polyp detection | 8.9% | 14.8% | 0.3a |

| Midazolam dose (mg), SD | 11.3 (3.8) | 8.6 (3.1) | < 0.001a |

Although there are no recent estimates, a substantial minority of GI endoscopic procedures in the United States continue to be performed with endoscopist administered midazolam and fentanyl sedation[1]. Given that in the United States, propofol must be administered by an anesthesia professional, endoscopist administered sedation is significantly more cost effective[8]. However, it should be noted that the choice of sedation depends on multiple factors: (1) Patient comorbidities and overall performance status; (2) Procedure invasiveness, duration, complexity, and chance of pain; (3) Experience and expertise of the provider with types of sedation; (4) Availability of anesthesia services and sedative agents; (5) Cost; and (6) Patient preference[9]. In the present study we found that in low risk outpatients (ASA classifications I and II) undergoing routine EGD and/or colonoscopy with no advanced interventions, sedation with midazolam alone was noninferior to midazolam plus fentanyl with regard to patient satisfaction, adverse events, and procedure quality. Despite the long history of midazolam/fentanyl sedation in GI endoscopy, there is a surprising dearth of data comparing single agent sedation with midazolam to standard midazolam/fentanyl sedation. There are valid reasons to question the routine use of fentanyl based on safety and patient tolerance[4,5]. Our study helps to fill this knowledge gap and suggests that further research is worthwhile.

Our study was limited by incomplete enrollment and all procedures having been done by a single endoscopist (author Greg S Cohen). The study protocol called for interim safety analysis after 300 patients were enrolled. Two other en

The single blind design of the study also presents a limitation, in that the actions of the endoscopist may have been impacted by the choice of sedation. The lack of any differences in safety or quality measures provides reassurance that this effect, if present, was unlikely to have been large. A double-blind design can be envisioned, but would require additional personnel and resources to dispense placebo vs fentanyl to the endoscopist.

Our results indicate that it may be possible to minimize or in many cases entirely avoid using fentanyl in moderate sedation for endoscopy. This has the potential to reduce sedation related side effects without compromising sedation efficacy. Specifically in the experience of author Greg S Cohen, in patients who report nausea with or without vomiting after previous procedures with midazolam/fentanyl sedation, this can be avoided by using single agent sedation with midazolam. Similarly, in patients requiring further sedation but who are experiencing intraprocedural hypotension with midazolam/fentanyl sedation, avoiding further fentanyl administration and giving midazolam alone can achieve effective sedation without worsening hypotension.

The only statistically significant differences we found between sedation groups were that when fentanyl is excluded, cecal intubation time was 1 minute longer and an average of 2.7 mg more of midazolam was used. The increase in cecal intubation time raises the possibility that more careful technique was required to minimize pain in the single-agent midazolam group. If this is the case, there may be endoscopist related factors, like the ability to reduce loops or avoid introducing loops during a colonoscopy, that make it possible for some endoscopists but not others to minimize or avoid using fentanyl in moderate sedation.

In low risk outpatients undergoing routine EGD and/or colonoscopy it may be possible to minimize or avoid using fentanyl during endoscopist administered moderate sedation for endoscopy. We present these findings with the hope that they will spur additional research in this under-investigated field.

| 1. | Lin OS. Sedation for routine gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures: a review on efficacy, safety, efficiency, cost and satisfaction. Intest Res. 2017;15:456-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lazaraki G, Kountouras J, Metallidis S, Dokas S, Bakaloudis T, Chatzopoulos D, Gavalas E, Zavos C. Single use of fentanyl in colonoscopy is safe and effective and significantly shortens recovery time. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1631-1636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Radaelli F, Meucci G, Terruzzi V, Spinzi G, Imperiali G, Strocchi E, Lenoci N, Terreni N, Mandelli G, Minoli G. Single bolus of midazolam versus bolus midazolam plus meperidine for colonoscopy: a prospective, randomized, double-blind trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:329-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Barriga J, Sachdev MS, Royall L, Brown G, Tombazzi CR. Sedation for upper endoscopy: comparison of midazolam versus fentanyl plus midazolam. South Med J. 2008;101:362-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Baris S, Karakaya D, Aykent R, Kirdar K, Sagkan O, Tür A. Comparison of midazolam with or without fentanyl for conscious sedation and hemodynamics in coronary angiography. Can J Cardiol. 2001;17:277-281. [PubMed] |

| 6. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Early DS, Lightdale JR, Vargo JJ 2nd, Acosta RD, Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi KV, Evans JA, Fisher DA, Fonkalsrud L, Hwang JH, Khashab MA, Muthusamy VR, Pasha SF, Saltzman JR, Shergill AK, Cash BD, DeWitt JM. Guidelines for sedation and anesthesia in GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:327-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 363] [Article Influence: 51.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Leffler DA, Bukoye B, Sawhney M, Berzin T, Sands K, Chowdary S, Shah A, Barnett S. Development and validation of the PROcedural Sedation Assessment Survey (PROSAS) for assessment of procedural sedation quality. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:194-203.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Goudra B, Gouda G, Mohinder P. Recent Developments in Drugs for GI Endoscopy Sedation. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65:2781-2788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lv LL, Zhang MM. Up-to-date literature review and issues of sedation during digestive endoscopy. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2023;18:418-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |