Published online Apr 16, 2019. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v11.i4.308

Peer-review started: February 17, 2019

First decision: March 11, 2019

Revised: March 27, 2019

Accepted: April 8, 2019

Article in press: April 9, 2019

Published online: April 16, 2019

Processing time: 60 Days and 11.1 Hours

Plasma-cell neoplasms rarely involve the gastrointestinal tract and manifest as gastrointestinal bleeding. Plasmablastic myeloma is an aggressive plasma cell neoplasm associated with poor outcomes. A small number of cases with gastrointestinal involvement is reported in the literature and therefore high index of suspicion is essential for avoiding delays in diagnosis and treatment.

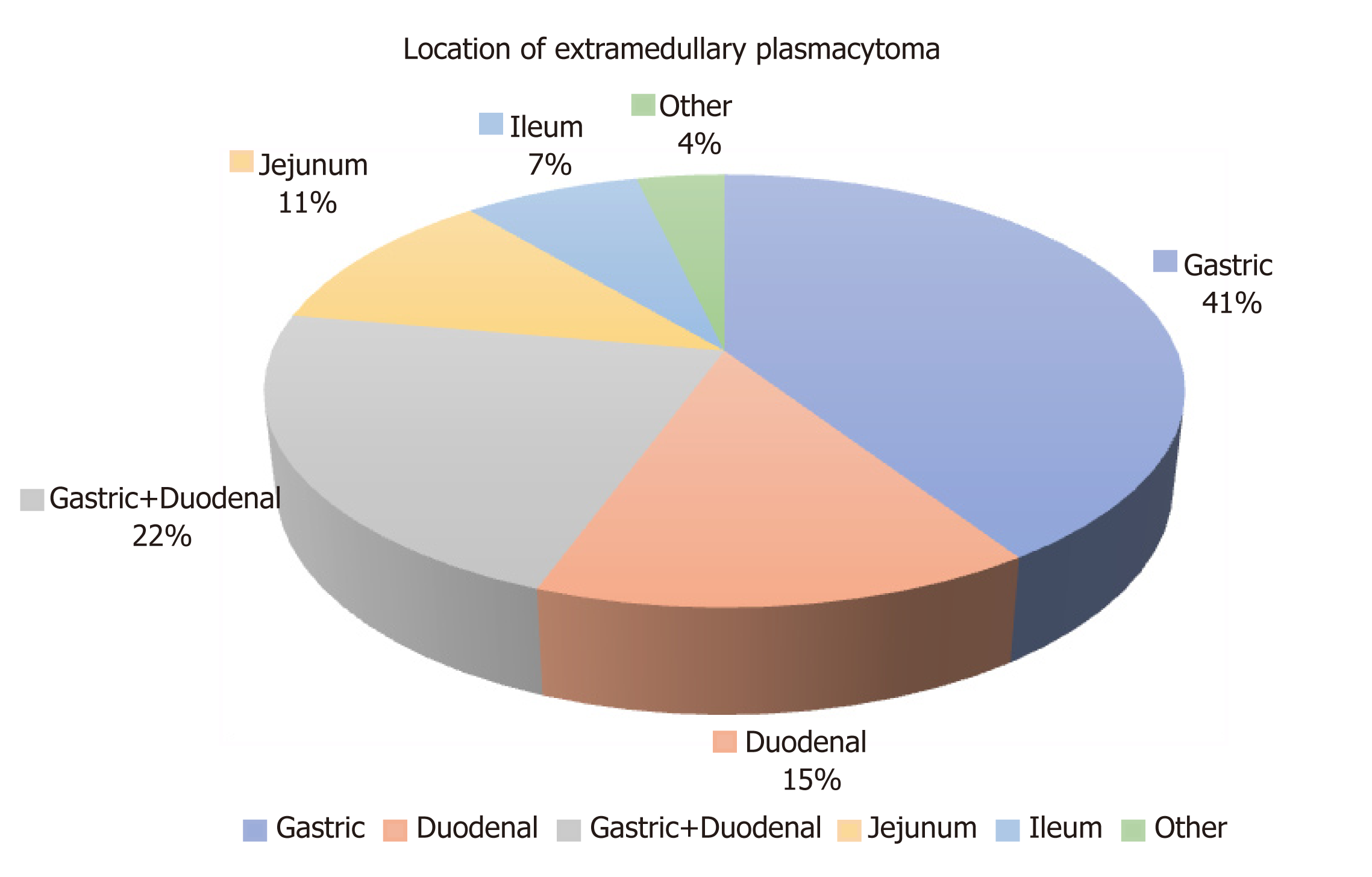

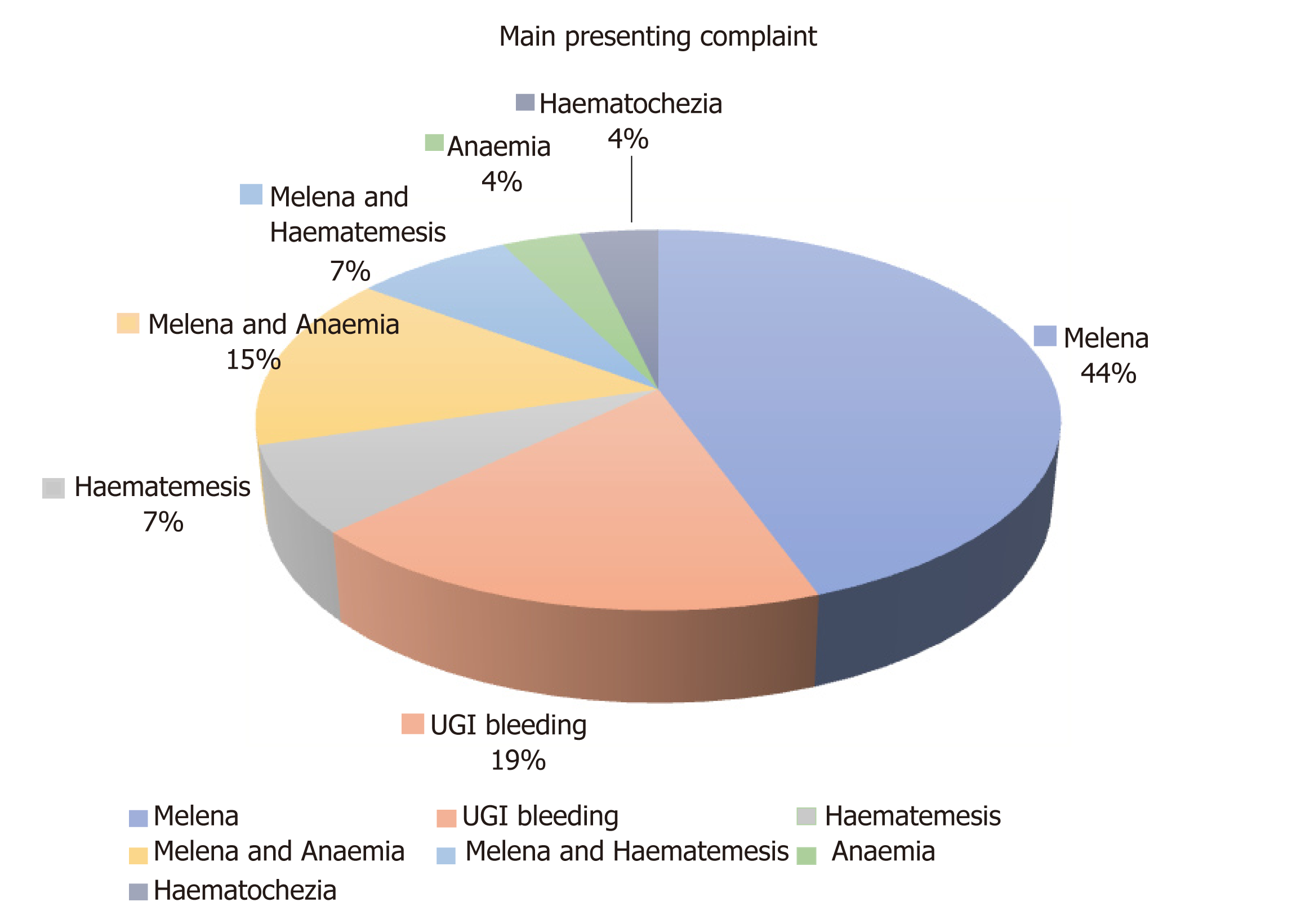

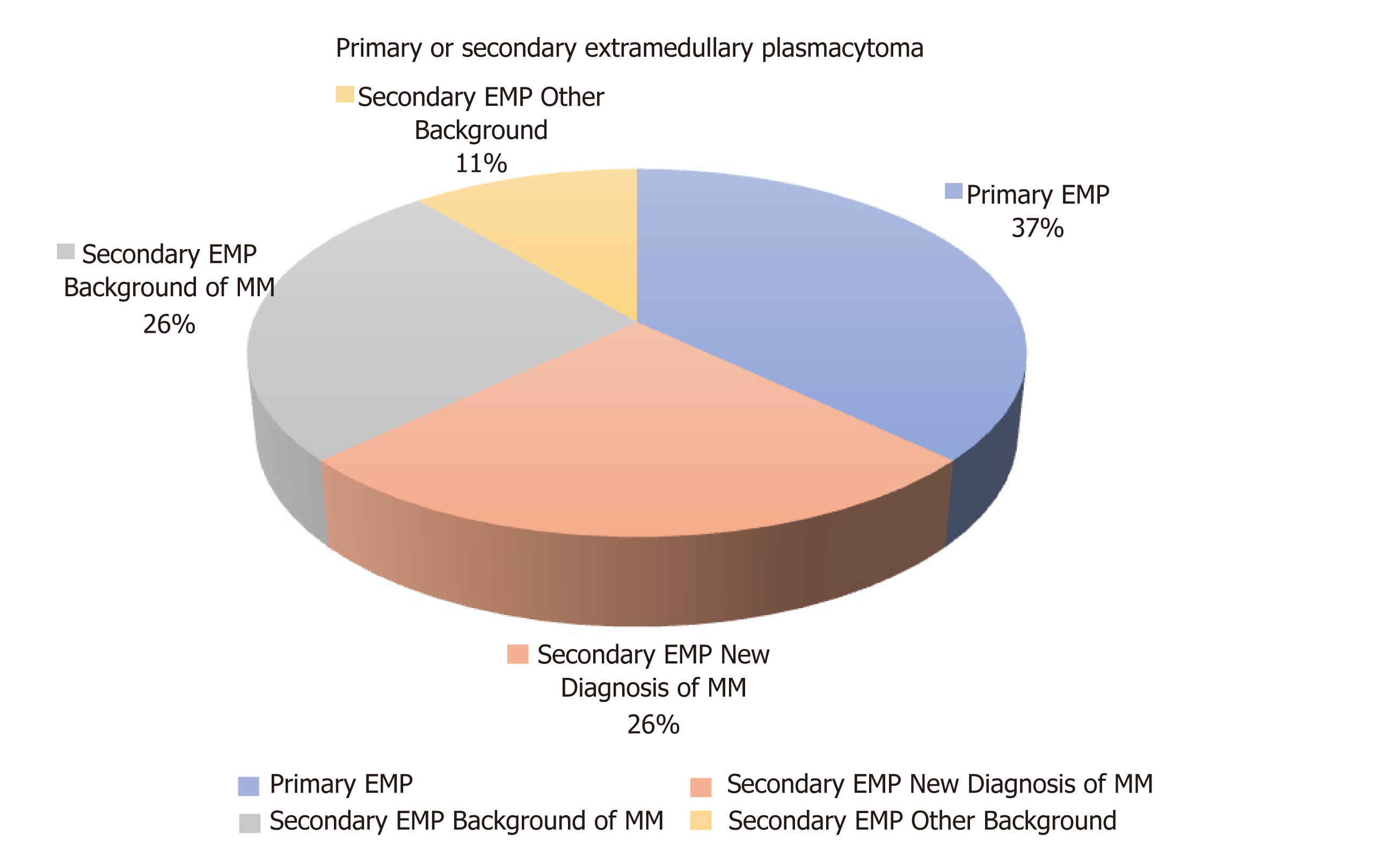

Our aim is to present our experience of a 70-year-old patient with a secondary presentation of plasmablastic myeloma manifesting as unstable upper gastrointestinal bleeding and to review the literature with the view to consolidate and discuss information about diagnosis and management of this rare entity. In addition to our case, a literature search (PubMed database) of case reports of extramedullary plasma cell neoplasms manifesting as upper gastrointestinal bleeding was performed. Twenty-seven cases of extramedullary plasmacytoma (EMP) involving the stomach and small bowel presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding were retrieved. The majority of patients were males (67%). The average age on diagnosis was 62.7 years. The most common site of presentation was the stomach (41%), followed by the duodenum (15%). The most common presenting complaint was melena (44%). In the majority of cases, the EMPs were a secondary manifestation (63%) at the background of multiple myeloma (26%), plasmablastic myeloma (7%) or high-grade plasma cell myeloma (4%). Oesophagogastroscopy was the main diagnostic modality and chemotherapy the preferred treatment option for secondary EMPs.

Despite their rare presentation, upper gastrointestinal EMPs should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with gastrointestinal bleeding especially in the presence of systemic haematological malignancy.

Core tip: The involvement of gastrointestinal tract by plasma cell neoplasms and the manifestation as gastrointestinal bleeding is very rare. However, patients can be profoundly unstable on presentation requiring immediate diagnosis and intervention. As the existing literature is very scattered and it mainly consists of case reports, we are aiming with our present work not only to describe our experience but also to review, consolidate and discuss information about diagnosis and management of this rare cause of gastrointestinal bleeding. The management these patients requires a multidisciplinary team approach and should involve not only the gastroenterology and surgical teams but also haematology and oncology teams for achievement of the best possible outcomes.

- Citation: Iosif E, Rees C, Beeslaar S, Shamali A, Lauro R, Kyriakides C. Gastrointestinal bleeding as initial presentation of extramedullary plasma cell neoplasms: A case report and review of the literature. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2019; 11(4): 308-321

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v11/i4/308.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v11.i4.308

Plasmablastic myeloma is a rare variant of multiple myeloma and is categorised amongst the plasma cell neoplasms. It is characterised by the neoplastic proliferation of a single clone of plasma cells which produces a monoclonal immunoglobulin. The malignant plasmablastic clones reside in the bone marrow but in rare occasions can migrate into extramedullary tissues like the upper respiratory tract, lymph nodes, central nervous system and gastrointestinal tract and present with symptoms or complications from the organs involved. Gastrointestinal involvement includes lesions in the stomach, liver and large bowel, with involvement of the small bowel being a rare presentation.

The most frequent manifestation of gastrointestinal tract extramedullary plasma cell neoplasm is abdominal pain which can be associated with symptoms of small bowel obstruction. Gastrointestinal bleeding can also occur, more often in gastric and jejunal lesions compared to ileal. It can present as haematemesis, melena or anaemia due to chronic blood loss due to vascular or ulcerated bleeding lesions[1,2]. The pathogenesis of gastrointestinal bleeding in plasma cell myelomas is multifactorial. Direct plasma cell infiltrates in the form of extramedullary plasmacytomas (EMPs)[2,3], coagulation abnormalities as a result of paraproteinaemia[4,5], peptic ulcers secondary to corticosteroid and anti-inflammatory therapeutic regimes and[2] finally amyloid infiltrates of the bowel wall[6]. Patients presenting with GI bleeding could be challenging in diagnosis and treatment, as they might be clinically unstable requiring an immediate intervention.

The literature is scattered with case reports of patients who have been affected with extramedullary plasma cell neoplasms with gastrointestinal tract involvement, especially with GI bleeding. We are aiming not only to describe our experience of one case of upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to secondary extramedullary plasma cell neoplasm but also to provide a comprehensive review of all published cases of stomach and small bowel EMPs to date with similar presentation.

This is a case of a 70-year-old male patient who initially presented to his oncologist at another hospital with right shoulder and neck pain associated with paraesthesia affecting the C8-T1 dermatome area. The patient was then admitted to our hospital under the gastroenterology team with fresh bleeding per rectum and melena.

Two-day history of melena and fresh PR bleeding without any abdominal pain.

His past medical history included essential hypertension, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation on beta blockers but not on anticoagulation, a prostatectomy (TURP) for cancer and still on hormone therapy for non- metastatic prostate cancer. To investigate his shoulder pain and paraesthesia he underwent (at his local hospital under oncology team) a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of his spine which revealed multiple bony lesions and a soft tissue lesion at the level of T8-T9 vertebrae. A staging computer tomography (CT) of chest, abdomen and pelvis did not reveal any additional pathology. To reduce the risk of cord compression urgent radiotherapy (five sessions) at T7-T10 level was given.

His family history was clear and didn’t include any haematological or gastrointestinal malignancies.

On examination patient was pale, clammy and sweaty, hypotensive but not markedly tachycardic (on beta blockers). His abdomen was soft, mildly tender in the centre but with no signs of peritonism. Digital rectal examination revealed the presence of fresh blood and melena in the rectum.

The patient’s haemoglobin on presentation was 58 g/L, MCV 92.3 fL, MCH 29 pg, MCHC 315 g/L consistent with normochromic normocytic anaemia and acute severe blood loss. His urea was raised 9.9 mmol/L sign of blood digestion in the upper gastrointestinal tract.

When the patient presented in our Centre, due to haemodynamic instability, after initial resuscitation and blood transfusion he had an oesophagogastroscopy which apart from mild gastritis showed no cause for his symptoms. A CT angiogram did not show any signs of active bleeding but mild prominence of the colonic hepatic flexure and the rectum was reported. A subsequent colonoscopy to the terminal 30cm of ileum reported large clots in the large and small bowel but no obvious bleeding point was demonstrated. Following this, he underwent a small bowel capsule endoscopy (Figure 1) which showed mid-small bowel bleeding from a likely submucosal lesion which was associated with intestinal lymphangiectasia. As he continued to bleed a further CT angiogram was performed. This last showed a potential small bowel mass with a contrast blush suggestive of slow haemorrhage, therefore the patient was taken to theatre for an emergency laparotomy and resection of the small bowel lesion.

The lesion was located at the proximal ileum (150 cm from DJ flexure), was resected and sent for histology and a primary side-to-side small bowel anastomosis was performed. There was no macroscopic evidence of lymphadenopathy, peritoneal or disseminated malignant disease intraoperatively. A segment of proximal ileum 95 mm in length was resected, which on opening, revealed a centrally ulcerated fungoid lesion which was 32 mm in maximum diameter and 40 mm from the nearest end resection margin. The lesion had a solid white appearance and involved the entire thickness of the bowel wall.

The patient had a smooth and uncomplicated post-operative recovery and was discharged from the hospital a week following his laparotomy.

Histopathology revealed sheets of pleomorphic cells which had a plasmacytoid appearance with highly atypical nuclei containing prominent nucleoli (Figure 2). On immunohistochemical staining the cells were positive for CD38 (Figure 3A), CD138 (Figure 3B), MUM-1 (Figure 3C), Ki 67 (MIB-1) (Figure 3D) with lambda light chain restriction (Figure 4). There was also weak nuclear expression for cyclin D1 in some of the cells. The morphological and immunophenotypical features were those of a high-grade plasma cell neoplasm.

Considering the presence of bony lytic lesions and IgG lambda paraproteinaemia (17 g/L, lambda light chains 84.1 mg/L) a diagnosis of plasma cell myeloma was given. A bone marrow biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of myeloma. This showed several markedly pleomorphic small nodular foci of tumour comprising plasmablastic cells with prominent nucleoli. Those cells, which represented 10%-15% of the marrow cellularity, were identical to the cells seen in the small bowel resection, confirming bone marrow involvement with an aggressive plasmablastic neoplasm. Bone marrow cytogenetic studies showed gain of 1q21.3, consistent with aggressive tumour behaviour.

After discussion in the local network haematology multidisciplinary team meeting a trial of VCD (Velcade/ Cyclophosphamide/ Dexamethasone) chemotherapeutic regimen was given, with a view to consolidative autologous stem cell transplantation in the event of a good response. Thalidomide was avoided initially in view of perceived thrombotic risk post-surgery. Despite reduction in his paraprotein to 7 g/L, clinical examination after 2 cycles of treatment showed clear progression of a soft tissue lesion arising from the right first rib and progression was confirmed on MRI and PET-CT imaging. He wished to continue active treatment and was commenced on second-line treatment with Bendamustine/Thalidomide/Dexamethasone, with a view to switching to Lenalidomide/Ixazomib/Dexamethasone therapy in the event of disease progression.

Due to disease progression, and no further response to active treatment, the patient was fast tracked with the palliative care team involvement to Hospice where he died six months after his diagnosis.

In addition to presenting and discussing our case, a literature search (PubMed database) was performed using the following searching terms: “extramedullary plasmacytoma”, “gastrointestinal plasmacytoma”, “gastrointestinal bleeding”, “small bowel extramedullary plasmacytoma”, “plasmablastic myeloma”. The search was limited to articles published in the English language. All published case reports presenting cases of EMP manifesting as upper gastrointestinal bleeding have been analysed. The following variables have been extracted, when available: patient’s age, gender, location of EMP in the gastrointestinal tract, presenting complaint, associated symptoms, primary or secondary nature of EMP, diagnostic modalities, treatment choices and outcomes. Cases involving colonic EMP and therefore not presented as upper gastrointestinal bleeding were excluded from the analysis. GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, United States) and Microsoft Excel (Version 16.15) were used to design the graphs extracted from our results.

Sixty-eight cases of EMP involving the upper gastrointestinal tract have been reported in the literature[1]. Twenty-seven cases, including our case of EMP involving the stomach and small bowel presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding were retrieved and have been included in our analysis. Patients’ characteristics (age, gender), presenting symptoms, tumour characteristics (location, primary or secondary nature), details about diagnostic and treatment modalities and all the available information about follow up and survival are shown on (Table 1). The majority of patients were males (67% vs 18% females) and details about gender were not available in four cases (15%). The average age on diagnosis was 62.7 years. In regards to the location of the EMPs, the most common site of presentation was the stomach (41%)[7-17], followed by the duodenum (15%)[18-21], but noticeable is the presence of concurrent lesions in stomach and duodenum (22%)[2,3,22-25]. Jejunal EMPs were less common (11%)[26-28], whereas ileal presentation was the rarest and was mentioned only in one more case report apart from our case (7%)[29]. A very rare presentation with concurrent lesions in the duodenum, jejunum and ileum was also mentioned[30] (Figure 5). A total of 18% of cases had localisation distal to the Treitz ligament and therefore diagnosis was difficult using oesophagogastroscopy.

| Ref. | Year | Age | Gender | Location of EMP | Presenting Complaint | Outcome | Other symptoms | Primary or Secondary | Diagnostic tests | Treatment |

| Line et al[7] | 1969 | 46 | Male | Gastric | Melena | Dead after 2 yr | Bone pain and swelling, weight loss, indigestion | Secondary | Barium meal, laparotomy | STx |

| Yasar et al[8] | 2015 | 69 | Male | Gastric | Melena, Haematemesis | N/A | None | Secondary (BG: MM) | OGD | N/A |

| Krishnamoorthy et al[9] | 2010 | 57 | Male | Gastric | Melena | N/A | None | Primary | OGD | N/A |

| Morinaga et al[10] | 2010 | 61 | Male | Gastric | Melena | N/A | Abdominal distention | Primary | CT AP OGD | N/A |

| Ruiz Montes et al[11] | 1995 | N/A | N/A | Gastric | Upper GI Bleeding | N/A | None | Primary | OGD | N/A |

| Katodritou et al[12] | 2008 | 68 | Male | Gastric | Upper GI Bleeding | Remission 13 mo post diagnosis | None | Primary | OGD | CTx (Bortezomib + Dexamethasone) |

| Chim et al[13] | 2002 | N/A | N/A | Gastric | Melena | N/A | N/A | Secondary (new Dx of MM) | OGD | N/A |

| Sanal et al[14] | 1996 | 75 | Male | Gastric | Melena | N/A | Obstructive jaundice (pancreatic plasmacytoma), bony lesions, Skin lesions | Secondary (BG: MM) | OGD | N/A |

| Güngör et al[15] | 2009 | 77 | Male | Gastric | Melena | N/A | Skin lesions | Secondary (BG: MM) | OGD | CTx |

| Daram et al[3] | 2012 | 53 | Female | Gastric Duodenal | Haematemesis | N/A | None | Secondary (BG: MM) | OGD | N/A |

| Sloyer et al[16] | 1988 | 60 | Male | Gastric | Melena | N/A | Bone pain (bony lesions) | Secondary (BG: MM) | OGD | N/A |

| Hamilton et al[17] | 1999 | 53 | Male | Gastric | Melena/Haematemesis | Dead in < 12 mo | Epigastric pain Previous orbital plasmacytoma | Secondary (new Dx of MM) | OGD | CTx |

| Maskin et al[22] | 2008 | 53 | Male | Gastric/Duodenal | UGI Bleeding | N/A | Back pain (bony lesions), Anorexia, Vomiting | Secondary (new Dx of MM) | OGD | N/A |

| Ammar et al[23] | 2010 | 69 | Female | Gastric/Duodenal | Melena | Alive (report in 2012) | Fatigue | Primary | OGD | RTx (Patient not fit for ChemoTx/Surg) PTC for subsequent biliary obstruction |

| Lin et al[2] | 2012 | 47 | Male | Gastric/Duodenal | Haemato -chezia | Alive for 6-mo follow up | Palpitations | Secondary (new Dx of MM) | OGD, small capsule endoscopy | CTx (Melphalan,prednisone, oral thalidomide) +/- Stem cell transplantation |

| Wang et al[24] | 2013 | 52 | Female | Gastric/Duodenal | Melena | Dead after 2 mo | Back pain, weakness (bony lesions), dyspnoea (pleural effusion) | Secondary (new Dx of MM) | OGD | N/A |

| Esfandyari et al[25] | 2007 | 70 | Male | Gastric/Duodenal | Anaemia | Dead | Astenia | Secondary (BG: MM) | OGD | CTx |

| Gradishar et al[18] | 1988 | 65 | Male | Duodenal | Melena | Alive (reported in 2012) | Abdominal pain, obstruction | Secondary (BG: MM) | OGD | RTx STx |

| Siddique et al[19] | 1999 | N/A | N/A | Duodenal | Melena | N/A | None | Primary | OGD | Gastroduodenal artery embolization |

| Fowell et al[20] | 2007 | 88 | Male | Duodenal | UGI Bleeding | N/A | Abdominal pain, dyspepsia, diarrhoea, fever, weight loss | Primary | OGD | N/A |

| Licci et al[21] | 2017 | 60 | Female | Duodenal | Melena Anaemia | N/A | Weight loss | Secondary (High-grade plasma cell myeloma) | OGD | CTx |

| Prachayakul et al[30] | 2013 | 48 | Male | Duodenumjejunum, ileum | UGI Bleeding | N/A | Abdominal pain + Diarrhoea Bony lesions | Secondary (new Dx of MM) | OGD | CTx |

| Ingegno et al[26] | 1954 | 51 | Female | Jejunum | Haematemesis | Alive after 32 mo | None | Primary | OGD | STx |

| Michotey et al[27] | 1970 | N/A | N/A | Jejunum | Melena, Anaemia | N/A | Abdominal pain | Primary | OGD | STx |

| Reddy et al[28] | 2015 | 69 | Male | Jejunum | Melena, Anaemia | N/A | None | Secondary (BG of plasmablastic myeloma) | OGD, Small bowel endoscopy, double balloon endero-scopy | CTx (cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, dexamethasone) +/- stem cell transplantation |

| Fisher et al[29] | 1975 | 81 | Male | Ileum | Melena | N/A | Obstruction, skin lesions, lymphadeno-pathy | Primary | OGD Laparotomy | STx |

| Monohan et al[31] | 2018 | 70 | Male | Ileum | Melena, Anaemia | Died 6 mo after diagnosis | Bony lesions | Secondary (BG of plasma-blastic myeloma) | OGD Colono-scopy Small capsule endoscopy CT Angiogram | CTx STx (emergency) |

Gastrointestinal bleeding in these cases had different presentations. The most common presenting complaint was melena (44%)[7,9,10,13-16,18,19,23,24,29] and four patients (15%) had melena associated with anaemia[21,27,28]. In five cases (19%), the gastrointestinal bleeding was reported as Upper gastrointestinal bleeding with no further clarification[11,12,20,22,30]. Haematemesis was the presenting complaint in 7% of cases[3,26] and concurrent melena and haematemesis in 7%[8,17]. One patient presented with haematochezia (4%)[2], and one patient was found to have secondary gastroduodenal EMP as part of his investigations for anaemia[25] (Figure 6).

In the majority of the cases analysed the EMPs were a secondary manifestation (63%) at the background of either multiple myeloma (26%)[3,8,14,16,18,25] or more rarely plasmablastic myeloma (7%)[28] or high-grade plasma cell myeloma (4%)[21]. However, there were ten cases (37%)[9-12,19,20,23,26,27,29] of primary EMPs not associated with systemic disease (Figure 7).

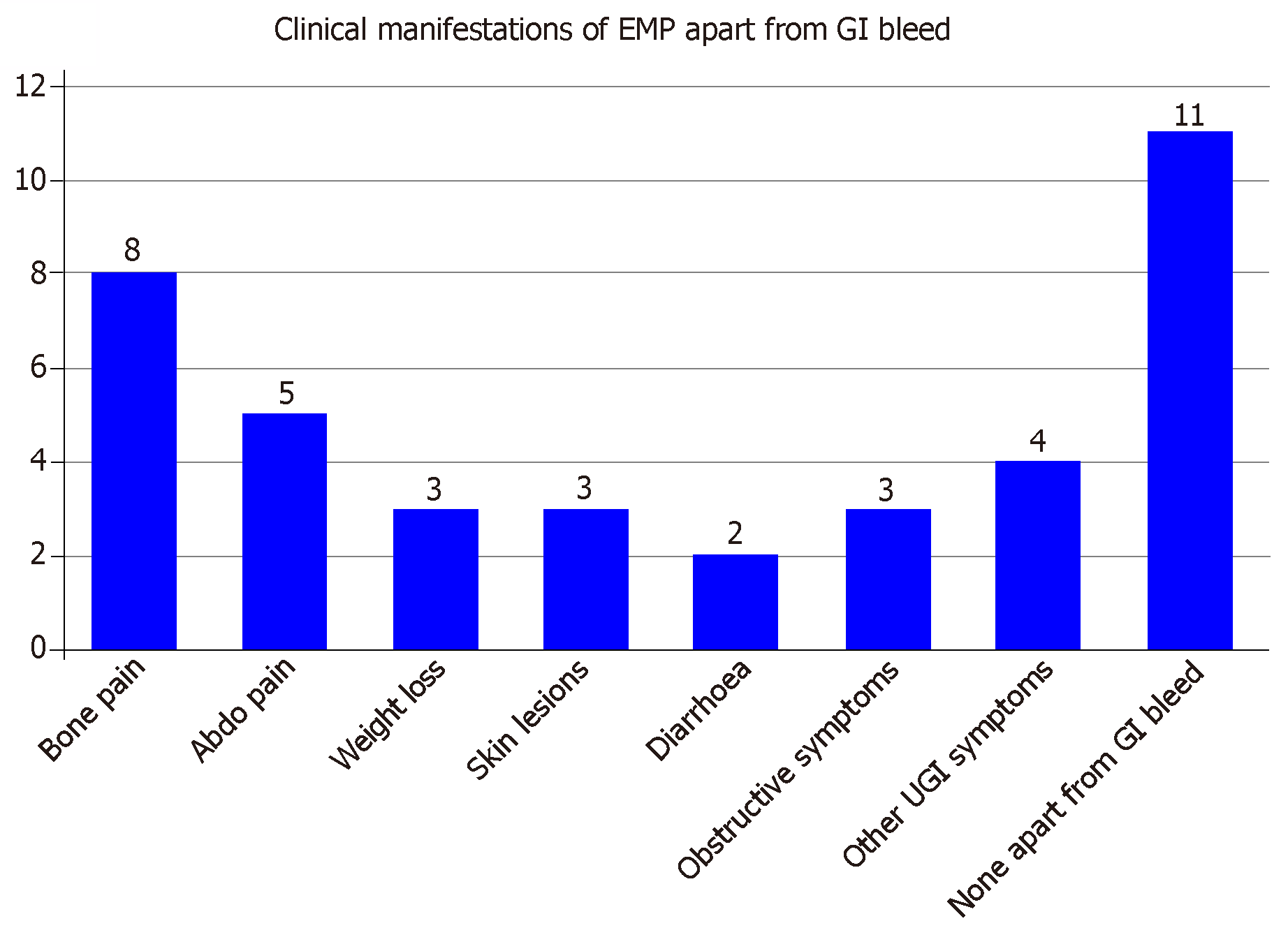

Apart from the gastrointestinal bleed, other frequent clinical manifestations are demonstrated in (Figure 8) and they include abdominal pain, diarrhoea, symptoms of bowel obstruction and other gastrointestinal symptoms (jaundice, dyspepsia and anorexia). Bone pain due to bony lesions, weight loss and skin lesions were also present in cases of secondary EMP.

Oesophagogastroscopy was the main initial diagnostic modality used in 26 out of the 27 cases analysed. For lesions located in jejunum and ileum, where Oesophagogastroscopy was not diagnostic further investigations (small bowel capsule endoscopy, CT angiogram, laparotomy) were used.

Unfortunately, we were unable to retrieve any data about the treatment eleven of the cases had because there was no information on the reports. For the remaining sixteen case reports there were ten cases of secondary EMP, eight of which received chemotherapy[2,15,17,21,25,28,30], only one radiotherapy due to patient’s co-morbid status[18] and three had surgical treatment[7,18]. The treatment modality selected for the remaining six cases of primary EMP varied between surgery in three cases[26,27,29], chemotherapy in one case[12], radiotherapy in one case[23] and embolization of gastroduodenal artery in one case[19]. Data about patients’ follow up and outcome were very scattered and incomplete and therefore no significant results and associations could be made.

Despite plasma cell neoplasms being a rare cause of gastrointestinal bleeding, patients affected could present clinically unstable requiring an immediate intervention and therefore, by presenting a review of the above mentioned twenty-seven cases, we have created a consolidative reference for further use not only by haematologists and oncologists, who are more familiar with the presentation, diagnosis and management of these rear entities but also for all the clinicians who deal with unstable patients with gastrointestinal tract bleeding on the acute setting.

Basic understanding of the biology of plasma cell neoplasms is fundamental. Plasma cell neoplasms have the mutual characteristic of neoplastic proliferation of a single clone of plasma cells which produces a monoclonal immunoglobulin[31,32]. Monoclonal immunoglobulin’s (M-protein) detection in the serum or urine indicates an underlying clonal plasma cell disorder and its level can be used to determine myeloma activity. M-protein’s properties are associated with the adverse effects that can be observed in patients with paraproteinaemia. These include its ability to agglutinate red blood cells causing increased blood viscosity and to bind into normal blood clotting factors causing bleeding and clotting abnormalities. In addition, its deposition in tissues can result in organ dysfunction and specifically its ability to bind to nerves can lead to neuropathy[32].

Plasmablastic myeloma is considered a rare variant of multiple myeloma and it is categorised amongst the plasma cell neoplasms. The diagnosis of plasma cell myeloma and subsequently the diagnosis of plasmablastic variant involves: (1) the presence of M-protein in serum or urine (usually > 30 g/L of IgG in serum or > 1g/24 h of urine light chain, but no minimal levels are designated); (2) the presence of monoclonal plasma cells in bone marrow biopsy (usually > 10% of the nucleated BM cells); and (3) evidence of organ or tissue impairment related to M-protein (hypercalcaemia, renal failure, anaemia, bony lytic lesions, hyperviscosity, recurrent infections)[33]. In the cases with extramedullary involvement and gastrointestinal manifestation with gastrointestinal bleeding, attempt for direct visualisation of the bleeding lesion is recommended with diagnostic and simultaneously therapeutic purposes. Oesophagogastroscopy was the main diagnostic modality used in the majority of the cases we have reviewed, during which biopsies are retrieved to provide histopathologic confirmation. However, 18% of cases were located distal to the Treitz ligament and therefore diagnosis was difficult using oesophagogastroscopy and further investigations were required.

Plasma cell neoplasms present distinct histopathological and immunohistochemical characteristics. Specifically, in plasmablastic myeloma, the abnormal plasma cells (plasmablasts) are large with hyperchromatic centrally placed nuclei (> 10 μm in diameter) and often prominent nucleoli. They have high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio and high mitotic activity[34]. Plasma cell aggregates composed of more than 10 plasma cells with perivascular distribution can be seen in one third of the myeloma bone marrow biopsies[35,36]. Pathological plasma cells express strong CD38, CD138 and light chain restriction. CD38 stains primarily the plasma cell cytoplasmic membrane due to expression of the transmembrane protein cyclic ADP ribose hydrolase and it is routinely used for identification of plasma cell neoplasms. CD138 (syndecan-1) is a transmembrane heparan sulphate proteoglycan which is present on the cytoplasmic membrane of up to 95% of plasma cells[36]. In addition, the low ratio of cytoplasmic κ to λ light chains favours the diagnosis of myeloma versus reactive plasmacytosis[37]. If plasmablasts comprise 2% or more of the nucleated cells in the bone marrow aspirate then the plasma cell myeloma can be classified as plasmablastic[34,38]. In general, plasmablastic morphologic features are associated with a poor clinical prognosis.

Plasmablastic myeloma is associated with frequent extramedullary involvement which is one of the features of clinical aggressiveness reflecting independence from the bone marrow stroma derived growth factors. Gastrointestinal involvement includes lesions in the stomach, liver and large bowel, with the involvement of the small bowel being a rare presentation, with 68 cases[1] been reported in literature currently. The most frequent manifestation of small bowel EMP is abdominal pain but gastrointestinal bleeding can also occur, more often in gastric and jejunal lesions compared to ileal. It can present as haematemesis, melena or anaemia due to chronic blood loss due to vascular or ulcerated bleeding lesions[1,2]. The pathogenesis of gastrointestinal bleeding in plasma cell myelomas is multifactorial. In the case of the ileal plasmablastic myeloma we described, gastrointestinal bleeding was attributed to the infiltration of the ileal wall with pleomorphic plasma cell infiltrates in the form of EMP and to the potential coagulopathy due to IgG lambda paraproteinaemia (level prior to treatment 17 g/L).

Once the patients are clinically stable and the diagnosis of extramedullary plasma cell neoplasm has been established, it is vital to confirm whether there is bone marrow involvement as this will not only affect the choice of treatment but also the prognosis[1]. The presence of clonal plasma cells in the bone marrow in association with the presence of M-protein in serum or urine and evidence of end organ dysfunction differentiates cases of secondary extramedullary involvement from cases of primary EMPs[28,33,39]. In general, primary EMPs have a more favourable prognosis than extramedullary manifestations of plasma cell myelomas.

The decision for the treatment pathway arises from multidisciplinary team discussions and it is usually in the form of local radiotherapy and surgery for cases of primary extramedullary plasma cell neoplasms and systemic chemotherapy for secondary neoplasms. Systemic therapy is in the form of induction chemotherapy with immunomodulatory agents (e.g., thalidomide), proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib) and corticosteroids (e.g., dexamethasone) which can be reinforced with autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation[1,32]. Autologous stem cell transplantation can prolong overall survival[40]. In our case, VCD regimen was attempted initially. Velcade (Bortezomib) is an inhibitor of ubiquitin-mediated proteasome degradation, and its combination with the alkylating agent cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone constitutes first line induction regimen. Due to progression of the disease we escalated to BTD regimen, introducing the thalidomide which it is broadly used in current practice for patients who relapse early after initial chemotherapy[41-43]. Thalidomide is a glutamic acid derivative which inhibits the production of tumour necrosis factor a (TNFa) and angiogenic cytokines inhibiting angiogenesis in plasma cell myelomas[32]. A thalidomide analogue, called lenalidomide can also be used in relapse refractory cases and was indeed used as third line in our case. Lenalidomide is a third-generation immunomodulatory medication with anti-TNF and anti-cancer activity[32,44,45].

The information provided in the cases we have reviewed about the outcome and prognosis of the patients with gastrointestinal bleeding is very scattered. However, we acknowledge the presence of poor prognostic factors for plasma cell neoplasms in literature. Plasmablastic variant tends to have worse prognosis than other plasma cell neoplasms[31]. The International staging system is used as a prognostic tool to estimate median survival based on the albumin and β2 microglobulin levels. Stage I with β2 microglobulin < 3.5 mg/L and albumin > 35g/L is associated with the best prognosis and a median survival of 62 mo. This was not the case with our patient who was categorised as ISS stage III on diagnosis with β2 microglobulin of > 5.5 mg/L and a median survival of 29 mo[32,46,47]. Numerous genetic alterations have also been associated with tumour progression and aggressive behaviour including chromosome 1q21 amplifications, and 1p deletions, KRAS and TP53 mutations and finally translocations of MYC[31], supporting the fact that cytogenetic or FISH analyses should be performed in all cases of plasma cell myelomas to define prognosis[33]. Further markers of poor prognosis and tumour aggressiveness that were demonstrated in our case was the nuclear expression of cyclin D1 at the small bowel segment, and the Ki-67 expression[48,49].

Although very rare in presentation, upper gastrointestinal extramedullary plasma cell tumours should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with gastrointestinal bleeding especially in the presence of a concurrent systemic haematological malignancy. The presence of gastrointestinal involvement and aggressive behaviour of this plasma cell neoplasm are associated with poor prognosis despite aggressive therapy and it is therefore fundamental to establish an accurate diagnosis early in order to avoid any delays in treatment.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Fiori E, Lee CL S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: A E-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Lopes da Silva R. Extramedullary plasmacytoma of the small intestine: clinical features, diagnosis and treatment. J Dig Dis. 2012;13:10-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lin M, Zhu J, Shen H, Huang J. Gastrointestinal bleeding as an initial manifestation in asymptomatic multiple myeloma: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:218-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Daram SR, Paine ER, Swingley AF. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding in a patient with multiple myeloma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:e8-e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | DiMinno G, Coraggio F, Cerbone AM, Capitanio AM, Manzo C, Spina M, Scarpato P, Dattoli GM, Mattioli PL, Mancini M. A myeloma paraprotein with specificity for platelet glycoprotein IIIa in a patient with a fatal bleeding disorder. J Clin Invest. 1986;77:157-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Saif MW, Allegra CJ, Greenberg B. Bleeding diathesis in multiple myeloma. J Hematother Stem Cell Res. 2001;10:657-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chang SS, Lu CL, Tsay SH, Chang FY, Lee SD. Amyloidosis-induced gastrointestinal bleeding in a patient with multiple myeloma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32:161-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Line DH, Lewis RH. Gastric plasmacytoma. Gut. 1969;10:230-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yasar B, Gunes P, Guler O, Yagcı S, Benek D. Extramedullary relapse of multiple myeloma presenting as massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a rare complication. Korean J Intern Med. 2015;30:538-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Krishnamoorthy N, Bal MM, Ramadwar M, Deodhar K, Mohandas KM. A rare case of primary gastric plasmacytoma: an unforeseen surprise. J Cancer Res Ther. 2010;6:549-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Morinaga R, Otsu S, Kashima K, Watanabe K. Extramedullary plasmacytoma as an uncommon cause of gastrorrhagia. Intern Med. 2010;49:1679-1680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ruiz Montes F, Reñé Espinet JM, Buenestado García J, Panades Siurana MJ, Egido García R, Ramos Yañez J. Primary gastric plasmacytoma of rapid growth presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1349-1350. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Katodritou E, Kartsios C, Gastari V, Verrou E, Mihou D, Banti A, Lazaraki G, Lazaridou A, Kaloutsi V, Zervas K. Successful treatment of extramedullary gastric plasmacytoma with the combination of bortezomib and dexamethasone: first reported case. Leuk Res. 2008;32:339-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chim CS, Wong WM, Nicholls J, Chung LP, Liang R. Extramedullary sites of involvement in hematologic malignancies: case 3. Hemorrhagic gastric plasmacytoma as the primary presentation in multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:344-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sanal SM, Yaylaci M, Mangold KA, Pantazis CG. Extensive extramedullary disease in myeloma. An uncommon variant with features of poor prognosis and dedifferentiation. Cancer. 1996;77:1298-1302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Güngör G, Göktepe MH, Kayaçetın E, Tuna T, Esen H, Demır A. Atypical gastrointestinal plasmacytomas presenting with gastrointestinal bleeding in a patient with multiple myeloma. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2012;23:85-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sloyer A, Katz S, Javors FA, Kahn E. Gastric involvement with excavated plasmacytoma: case report and review of endoscopic criteria. Endoscopy. 1988;20:267-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hamilton JW, McCluggage WG, Jones F, Collins J. Extramedullary gastric plasmacytoma. Ulster Med J. 1999;68:103-105. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Gradishar W, Recant W, Shapiro C. Obstructing plasmacytoma of the duodenum: first manifestation of relapsed multiple myeloma. Am J Gastroenterol. 1988;83:77-79. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Siddique I, Papadakis KA, Weber DM, Glober G. Recurrent bleeding from a duodenal plasmacytoma treated successfully with embolization of the gastroduodenal artery. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1691-1692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fowell AJ, Poller DN, Ellis RD. Diffuse luminal ulceration resulting from duodenal plasmacytoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:707-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Licci S. Duodenal localization of plasmablastic myeloma. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2017;8:93-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Maskin LP, Díaz MF, Hlavnicka A, Rubio H, de la Cámara A, Gastaminza MM, Wainsztein NA. Gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to multiple gastric plasmacytoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2008;31:100-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ammar T, Kreisel F, Ciorba MA. Primary antral duodenal extramedullary plasmacytoma presenting with melena. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:A32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wang CC, Chang MH, Lin CC. A rare cause of gastrointestinal bleeding. Multiple myeloma with extramedullary gastroduodenal plasmacytoma. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:e1-e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Esfandyari T, Abraham SC, Arora AS. Gastrointestinal plasmacytoma that caused anemia in a patient with multiple myeloma. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4:111-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | INGEGNO AP. Plasmacytoma of the gastrointestinal tract: report of a case involving the jejunum and review of the literature. Gastroenterology. 1954;26:89-102. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Michotey G, Brunel R. [Plasmacytoma of the small intestine. A case revealed by a perforation]. Arch Fr Mal App Dig. 1970;59:270-271. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Reddy R, Vohra S, Macurak R. Secondary Extramedullary Plasmablastic Myeloma of the Small Bowel. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:A23-A24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Fisher B, Klein DL. Metastasizing plasma cell tumor of the small bowel. Am J Gastroenterol. 1975;64:371-375. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Prachayakul V, Aswakul P, Deesomsak M, Pongpaibul A. Multifocal plasmacytoma presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding, chronic diarrhea, and multiple sites of small-bowel intussusception. Endoscopy. 2013;45 Suppl 2 UCTN:E84-E85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Monohan G. Plasmablastic Myeloma versus Plasmablastic Lymphoma: Different Yet Related Diseases. IJHT. 2018;6:25-8. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Cook L, Macdonald DH. Management of paraproteinaemia. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:217-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Campo E, Swerdlow SH, Harris NL, Pileri S, Stein H, Jaffe ES. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms and beyond: evolving concepts and practical applications. Blood. 2011;117:5019-5032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1268] [Cited by in RCA: 1446] [Article Influence: 103.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Srija M, Zachariah PP, Unni VN, Mathew A, Rajesh R, Kurian G, Neeraj S, Seethalekshmi NV, Smitha NV. Plasmablastic myeloma presenting as rapidly progressive renal failure in a young adult. Indian J Nephrol. 2014;24:41-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Sukpanichnant S, Cousar JB, Leelasiri A, Graber SE, Greer JP, Collins RD. Diagnostic criteria and histologic grading in multiple myeloma: histologic and immunohistologic analysis of 176 cases with clinical correlation. Hum Pathol. 1994;25:308-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Wei A, Juneja S. Bone marrow immunohistology of plasma cell neoplasms. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:406-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Eckert F, Schmid L, Kradolfer D, Schmid U. Bone-marrow plasmocytosis--an immunohistological study. Blut. 1986;53:11-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Goasguen JE, Zandecki M, Mathiot C, Scheiff JM, Bizet M, Ly-Sunnaram B, Grosbois B, Monconduit M, Michaux JL, Facon T. Mature plasma cells as indicator of better prognosis in multiple myeloma. New methodology for the assessment of plasma cell morphology. Leuk Res. 1999;23:1133-1140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | International Myeloma Working Group. Criteria for the classification of monoclonal gammopathies, multiple myeloma and related disorders: a report of the International Myeloma Working Group. Br J Haematol. 2003;121:749-757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1610] [Cited by in RCA: 1513] [Article Influence: 68.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 40. | Attal M, Harousseau JL, Stoppa AM, Sotto JJ, Fuzibet JG, Rossi JF, Casassus P, Maisonneuve H, Facon T, Ifrah N, Payen C, Bataille R. A prospective, randomized trial of autologous bone marrow transplantation and chemotherapy in multiple myeloma. Intergroupe Français du Myélome. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:91-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2135] [Cited by in RCA: 2048] [Article Influence: 70.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Barlogie B, Desikan R, Eddlemon P, Spencer T, Zeldis J, Munshi N, Badros A, Zangari M, Anaissie E, Epstein J, Shaughnessy J, Ayers D, Spoon D, Tricot G. Extended survival in advanced and refractory multiple myeloma after single-agent thalidomide: identification of prognostic factors in a phase 2 study of 169 patients. Blood. 2001;98:492-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 413] [Cited by in RCA: 377] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Palumbo A, Giaccone L, Bertola A, Pregno P, Bringhen S, Rus C, Triolo S, Gallo E, Pileri A, Boccadoro M. Low-dose thalidomide plus dexamethasone is an effective salvage therapy for advanced myeloma. Haematologica. 2001;86:399-403. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Palumbo A, Bertola A, Falco P, Rosato R, Cavallo F, Giaccone L, Bringhen S, Musto P, Pregno P, Caravita T, Ciccone G, Boccadoro M. Efficacy of low-dose thalidomide and dexamethasone as first salvage regimen in multiple myeloma. Hematol J. 2004;5:318-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Mazumder A, Jagannath S. Thalidomide and lenalidomide in multiple myeloma. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2006;19:769-780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Mazumder A, Kaufman J, Niesvizky R, Lonial S, Vesole D, Jagannath S. Effect of lenalidomide therapy on mobilization of peripheral blood stem cells in previously untreated multiple myeloma patients. Leukemia. 2008;22:1280-1; author reply 1281-2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Anderson KC, Alsina M, Atanackovic D, Biermann JS, Chandler JC, Costello C, Djulbegovic B, Fung HC, Gasparetto C, Godby K, Hofmeister C, Holmberg L, Holstein S, Huff CA, Kassim A, Krishnan AY, Kumar SK, Liedtke M, Lunning M, Raje N, Singhal S, Smith C, Somlo G, Stockerl-Goldstein K, Treon SP, Weber D, Yahalom J, Shead DA, Kumar R; National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Multiple Myeloma, Version 2.2016: Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13:1398-1435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Smith A, Wisloff F, Samson D; UK Myeloma Forum; Nordic Myeloma Study Group; British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of multiple myeloma 2005. Br J Haematol. 2006;132:410-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Athanasiou E, Kaloutsi V, Kotoula V, Hytiroglou P, Kostopoulos I, Zervas C, Kalogiannidis P, Fassas A, Christakis JI, Papadimitriou CS. Cyclin D1 overexpression in multiple myeloma. A morphologic, immunohistochemical, and in situ hybridization study of 71 paraffin-embedded bone marrow biopsy specimens. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001;116:535-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Drach J, Gattringer C, Glassl H, Drach D, Huber H. The biological and clinical significance of the KI-67 growth fraction in multiple myeloma. Hematol Oncol. 1992;10:125-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |