Published online Dec 28, 2017. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v9.i36.1385

Peer-review started: September 22, 2017

First decision: October 17, 2017

Revised: October 21, 2017

Accepted: November 11, 2017

Article in press: November 12, 2017

Published online: December 28, 2017

Processing time: 96 Days and 23.9 Hours

Eosinophilic cholangitis is a rare cause of deranged obstructive liver function tests. It has been described as a great mimicker for malignant biliary strictures and bile duct obstruction. There are only case reports available on treatment experience for eosinophilic cholangitis. A large proportion of patients present with biliary strictures for which they have undergone surgery or endoscopic treatment and a small proportion was given systemic corticosteroid. We share our treatment experience using budesonide which has fewer systemic side effects to prednisolone and avoids invasive management.

Core tip: Eosinophilic cholangitis is a rare cause of obstructive liver function tests and secondary sclerosing cholangitis. Peripheral eosinophilia is the most useful laboratory hint for the diagnosis thus avoiding invasive endoscopic or surgical treatment. It is normally treated with a prolonged duration of corticosteroids, risking the development of corticosteroid adverse effects. We describe our successful experience with budesonide, an alternative treatment option which has a higher first pass effect resulting in fewer systemic side effects.

- Citation: De Roza MA, Lim CH. Eosinophilic cholangitis treatment with budesonide. World J Hepatol 2017; 9(36): 1385-1388

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v9/i36/1385.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v9.i36.1385

Eosinophilic cholangitis is a rare cause of obstructive liver function tests. It has been described as a great mimicker for malignant biliary strictures and bile duct obstruction. There are only case reports available on treatment experience for eosinophilic cholangitis. A large proportion of patients present with biliary strictures for which they have undergone surgery or endoscopic treatment. A smaller proportion was given corticosteroid treatment and most involved the use of systemic corticosteroids such as prednisolone.

Our patient is a 75-year-old Chinese retired lady. She does not smoke, consume alcohol or substances. Past medical history of note is hypertension and septic arthritis with a right first metatarsal osteomyelitis for which she underwent a Ray’s amputation and was discharged to a step-down facility for slow stream rehabilitation.

She presented with deranged liver function tests (LFT), done during routine follow up at her rehabilitation centre. She was otherwise asymptomatic with no abdominal pain, fever, nausea, vomiting or diarrhoea. She did not take any supplements or over the counter medications. She was prescribed two weeks of antibiotics (one week of cefazolin followed by one week of oral Augmentin) for osteomyelitis which was treated with ray’s amputation. However, her antibiotic course was completed almost 2 mo prior to presentation.

Her baseline LFT (taken during admission for osteomyelitis) was unremarkable except for a mildly raised Alkaline Phosphatase which we attributed to her bone infection. Her baseline LFT was as such: Albumin 38 g/L (normal range 40-51 g/L), bilirubin 11 μmol/L (normal range 7-32 μmol/L), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 126 U/L (normal range 39-99 U/L), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 14 U/L (normal range 6-66 U/L), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 24 U/L (normal range 6-66 U/L).

She was referred to us 2 mo later with a predominantly cholestatic LFT and eosinophilia with markedly raised serum IgE levels. Her test results are as follows: Albumin 34 g/L, (normal range 40-51 g/L), bilirubin 20 μmol/L, (normal range 7-32 μmol/L), ALP 803 U/L, (normal range 39-99 U/L), ALT 234 U/L, (normal range 6-66 U/L), AST 145 U/L, (normal range 6-66 U/L), GGT 667 U/L (normal range 14-94 U/L), total leukocyte count 7.75 × 109/L (normal range 4.0-10.09/L), eosinophils 23.1% (normal range 0-6%), eosinophil absolute count 1.79 × 109/L (normal range 0.04-0.44 × 109/L), IgG, serum 12.08 g/L (normal range 5.49-17.11 g/L), IgA, serum 2.54 g/L (normal range 0.47-3.59 g/L), IgE, serum 1064 IU/ml (normal range 18-100 IU/mL).

Anti-MPO, Anti-PR3, Antinuclear Antibody, Anti Liver Antibodies (including M2, LKM-1, LC-1, SLA/LP) and Anti Smooth Muscle Antibody were all negative.

Serologies for hepatitis A, B, C, E and Human Immunodeficiency Virus were negative as well. Her renal function was normal.

She has no history of allergies or atopy and stool samples sent for parasites were negative twice. She had no new symptoms, had a good appetite without weight loss and was well and stable with no other organ involvement.

She underwent an ultrasound of the abdomen which showed a prominent pancreatic duct and biliary sludge in the gallbladder. It was normal otherwise with a negative sonographic Murphy’s sign. There were no gallstones, no biliary tree dilation and the common bile duct (CBD) measured 5 mm.

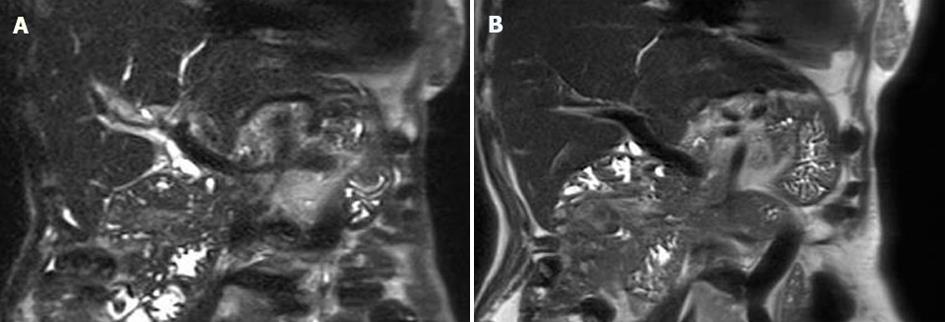

She was further investigated with a magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) which showed stones in the gallbladder with no evidence of cholecystitis. There was also prominence of the CBD at 9mm without a centrally obstructing stone, stricture or definite mass. The pancreatic duct was prominent with borderline dilated calibre but no obstructing lesion was detected. There were also several prominent/borderline dilated subsegmental ducts in segment VIII, V and II, and underlying strictures with mild periportal oedema (Figure 1).

Our patient went on to do an endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) for further evaluation of her CBD and PD prominence and exclude an ampullary lesion. The EUS showed a mildly thickened CBD wall which was unremarkable endosonographically. The biliary tree was not dilated. No intervention was done as there were no significant endosonographic abnormalities.

Our working diagnosis was Eosinophilic Cholangitis in view of the biliary strictures and dilation seen on MRCP with eosinophilia and raised serum IgE.

We have excluded biliary stones and an ampullary tumour. Autoimmune and viral serology were also negative. Drug induced liver injury was unlikely as she had no exposure.

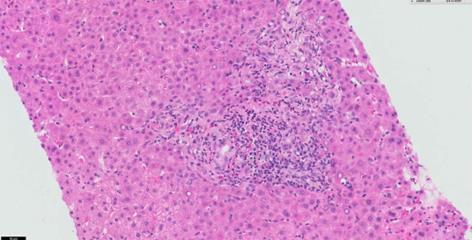

A liver biopsy was performed which confirmed portal and bile duct inflammation with a significant number of eosinophils of up to 18 per HPF (Figure 2). There was mild to moderate portal inflammatory cell infiltrate, predominantly composed of neutrophils and lymphocytes with moderate numbers of eosinophils. There was also bile ductular proliferation and portal tract oedema. No evidence of ductopenia, florid duct lesion, cholestasis, granuloma or neoplasia. Special stains did not show evidence of fibrosis. There was no conspicuous HBsAg, copper-associated protein, PASD positive or significant iron deposits. No increase in IgG4 positive cells were noted on immunohistochemistry.

Our patient was started on oral budesonide 9 mg/d. After one month of oral budesonide, her eosinophilia resolved and her LFT showed marked improvement with almost halved ALP (476 U/L) and ALT (125 U/L) values. Her LFT normalised after 6 mo. The patient declined a repeat liver biopsy but a repeat MRCP was done at 4 mo of treatment and showed overall improvement of the biliary dilation and strictures seen previously. Her oral budesonide was tapered down after 6 mo and subsequently discontinued after 9 mo.

Eosinophilic cholangitis (EC) is an uncommon and unknown cause of indeterminate biliary stricture and there is no consensus on a diagnostic criterion available. Matsumoto et al[1] proposed the following findings to diagnose EC: (1) Wall thickening or stenosis of the biliary system; (2) histopathological findings of eosinophilic infiltration; and (3) reversibility of biliary abnormalities without treatment or following steroid treatment.

The degree of eosinophilic infiltration has not been established either. In fact, there are case reports of Eosinophilic cholangitis with normal liver biopsies[2]. As a general guideline, Eos/HPF are significant when > 15 in the gastrointestinal tract but this has not been specified in EC[3]. Peripheral eosinophilia and obstructive liver function tests results are helpful laboratory findings to consider the diagnosis of EC. However, peripheral eosinophilia is only present in about two-third of cases[4].

A review of 23 cases of eosinophilic cholangitis showed that eight (34.8%) had complete resolution of symptoms with surgery alone and seven (30.4%) improved with the use of oral corticosteroids. The remaining six cases needed a combination of surgery and oral corticosteroids for resolution[4]. Most treatment experience with steroids for eosinophilic cholangitis was with prednisolone.

Budesonide is a corticosteroid immunosuppressive agent that results in interference with cytokine production and inhibition of T lymphocyte activation. It is a second-generation corticosteroid with an affinity for the glucocorticoid receptor that is approximately 15 times greater than that of prednisolone. When taken orally, it has a 90% first-pass metabolism in the liver, allowing it to reach high intrahepatic concentrations before its elimination, significantly limiting its systemic effects[5]. Budesonide has been compared to prednisolone and found to be more effective with fewer adverse effects than prednisolone for liver specific disease such as autoimmune hepatitis[6]. It is prescribed at a dose of 9 mg once a day and shown to be effective in patients with active Crohn’s disease and autoimmune hepatitis[7]. Hence, we chose to use budesonide at a dose of 9 mg once a day for our patient based on known evidence of its efficacy at this dose.

EC is a benign condition and should be managed with a trial of corticosteroids before considering more invasive treatment. A recent retrospective study showed an EC prevalence of 2.2% from a cohort of 135 cases of sclerosing cholangitis and post-hoc diagnosis of EC was ascertained in 30% (3/10) of patients where no cause of indeterminate biliary stricture was identified[8]. Our patient was on oral budesonide treatment for 9 mo with biochemical resolution of her eosinophilia and liver function test. She did not exhibit adverse effects from budesonide therapy on outpatient follow up. This case report is the first, to our knowledge, to treat EC with budesonide.

Deranged liver function test with a cholestatic pattern, eosinophilia, raised IgE, intrahepatic biliary stricture.

Eosinophilic cholangitis.

Biliary stone, pancreaticobiliary malignancy, drug induced liver injury.

Eosinophilic cholangitis.

Biliary stricture and dilation.

Eosinophilic cholangitis.

Budesonide 9 mg once a day.

There are no previous reports of treating eosinophilic cholangitis with Budesonide. But there are reports of successful treatment with prednisolone. Please see reference No. 2.

This is a rare case of eosinophilic cholangitis and the first time in literature, to be successfully treated with budesonide. The patient did not experience any side effects or steroid toxicity. In the future, with further evidence, budesonide might be a reasonable first line treatment for eosinophilic cholangitis as it is safer than prednisolone.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Singapore

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Fair): 0

P- Reviewer: Dogan UB, Kaya M, Kitamura K, Yan SL S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Song XX

| 1. | Matsumoto N, Yokoyama K, Nakai K, Yamamoto T, Otani T, Ogawa M, Tanaka N, Iwasaki A, Arakawa Y, Sugitani M. A case of eosinophilic cholangitis: imaging findings of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography, cholangioscopy, and intraductal ultrasonography. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1995-1997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fragulidis GP, Vezakis AI, Kontis EA, Pantiora EV, Stefanidis GG, Politi AN, Koutoulidis VK, Mela MK, Polydorou AA. Eosinophilic Cholangitis--A Challenging Diagnosis of Benign Biliary Stricture: A Case Report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e2394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Katzka DA; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: Evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:679-92; quiz 693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 784] [Cited by in RCA: 844] [Article Influence: 70.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nashed C, Sakpal SV, Shusharina V, Chamberlain RS. Eosinophilic cholangitis and cholangiopathy: a sheep in wolves clothing. HPB Surg. 2010;2010:906496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zandieh I, Krygier D, Wong V, Howard J, Worobetz L, Minuk G, Witt-Sullivan H, Yoshida EM. The use of budesonide in the treatment of autoimmune hepatitis in Canada. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22:388-392. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Manns MP, Woynarowski M, Kreisel W, Lurie Y, Rust C, Zuckerman E, Bahr MJ, Günther R, Hultcrantz RW, Spengler U. Budesonide induces remission more effectively than prednisone in a controlled trial of patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1198-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 349] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Greenberg GR, Feagan BG, Martin F, Sutherland LR, Thomson AB, Williams CN, Nilsson LG, Persson T. Oral budesonide for active Crohn’s disease. Canadian Inflammatory Bowel Disease Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:836-841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 392] [Cited by in RCA: 348] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Walter D, Hartmann S, Herrmann E, Peveling-Oberhag J, Bechstein WO, Zeuzem S, Hansmann ML, Friedrich-Rust M, Albert JG. Eosinophilic cholangitis is a potentially underdiagnosed etiology in indeterminate biliary stricture. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:1044-1050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |