Published online Jun 28, 2016. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v8.i18.779

Peer-review started: March 31, 2016

First decision: May 17, 2016

Revised: May 27, 2016

Accepted: June 1, 2016

Article in press: June 3, 2016

Published online: June 28, 2016

Processing time: 85 Days and 20.5 Hours

Classically, hepatic artery pseudoaneurysms (HAPs) arise secondary to trauma or iatrogenic causes. With an increasing prevalence of laparoscopic procedures of the hepatobiliary system the risk of inadvertent injury to arterial vessels is increased. Pseudoaneurysm formation post injury can lead to serious consequences of rupture and subsequent hemorrhage, therefore intervention in all identified visceral pseudoaneurysms has been advocated. A variety of interventional methods have been proposed, with surgical management becoming the last step intervention when minimally invasive therapies have failed. The authors present a case of a HAP in a 56-year-old female presenting with jaundice and pruritis suggestive of a Klatskin’s tumor. This presentation of HAP in a patient without any significant past medical or surgical intervention is atypical when considering that the majority of HAP cases present secondary to iatrogenic causes or trauma. Multiple minimally invasive approaches were employed in an attempt to alleviate the symptomology which included jaundice and associated inflammatory changes. Ultimately, a right hepatic trisegmentectomy was required to adequately relieve the mass effect on biliary outflow obstruction and definitively address the HAP. The presentation of a HAP masquerading as a malignancy with jaundice and pruritis, rather than the classic symptoms of abdominal pain, anemia, and melena, is unique. This presentation is only further complicated by the absent history of either trauma or instrumentation. It is important to be aware of HAPs as a potential cause of jaundice in addition to the more commonly thought of etiologies. Furthermore, given the morbidity and mortality associated with pseudoaneurysm rupture, intervention in identifiable cases, either by minimally invasive or surgical interventions, is recommended.

Core tip: Hepatic artery pseudoaneurysms (HAPs) typically arise from secondary trauma or iatrogenic causes. Most of HAPs are asymptomatic but can be complicated with rupture and bleeding. Biliary obstruction due to HAPs is a rare phenomenon and can present clinically as Quinke’s triad (hematobilia, abdominal pain, and jaundice). Most cases can be managed with non-operative vascular and endoscopic interventions. This case report presents an atypical presentation of HAP with a multidisciplinary approach to a complex problem.

- Citation: Luckhurst CM, Perez C, Collinsworth AL, Trevino JG. Atypical presentation of a hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm: A case report and review of the literature. World J Hepatol 2016; 8(18): 779-784

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v8/i18/779.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v8.i18.779

Hepatic artery pseudoaneurysms (HAPs), or false aneurysms, classically arise secondary to trauma or iatrogenic causes and pose a serious risk of exsanguinating hemorrhage and subsequent death[1,2]. Numerous case reports have been published addressing the occurrence of HAPs subsequent to a variety of interventional procedures including cholecystectomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy, and orthotopic liver transplant. It has been hypothesized that with the increasing frequency of laparoscopic procedures, such as cholecystectomy, which can result in inadvertent injury to the right hepatic artery, the overall incidence of HAPs will continue to rise[1,3]. Due to the increased risk of rupture compared with true aneurysms, some have advocated intervention in all cases of identifiable visceral pseudoaneurysm[4]. It has been reported that HAPs have been successfully treated using a variety of interventional methods, including endovascular embolization, coiling embolization, and arterial stent grafting[1,2]. Because of the increased morbidity associated with surgery in this setting, surgical management is the final treatment option when these subsequent methods have failed. Although in most cases interventional technologies can quench the risk of hemorrhagic rupture of HAP and alleviate biliary obstruction[5], surgical management of impairment to adjacent structures such as the bile duct and portal vein have to our knowledge ever been reported.

Here we provide a unique case of HAP, initially presenting as a Klatskin tumor (tumor at the confluence of the right and left hepatic biliary confluence) mimic and with no identifiable cause. Furthermore, the aforementioned treatment options were inadequate to address this persistent and recurrent chronic HAP, ultimately requiring surgical intervention.

A 65-year-old female with no significant past medical history was transferred from an outside institution for further management of painless jaundice and pruritis, with suspicion for a Klatskin’s tumor. At this outside institution, non-contrast computed tomography (CT) imaging studies revealed a 5 cm dense lesion within the hilar region of the liver and intrahepatic biliary duct dilatation. Subsequent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography showed a hilar obstructive lesion that was concerning for cholangiocarcinoma/Klatskin’s tumor. A temporary hepatic duct stent was placed and sphincterotomy was performed. Cytology results from this procedure were negative. On the day of her transfer, she was afebrile but was placed on empiric antibiotic coverage. Her total and direct bilirubin levels were elevated (total bilirubin 24.3 mg/dL, direct dilirubin 18.6 mg/dL), as was her serum alkaline phosphatase (432 U/L), liver transaminases (AST 132 U/L, ALT 148 U/L), and CA 19-9 (891 U/mL). Other pertinent labs included a positive ANA and CEA within the reference range.

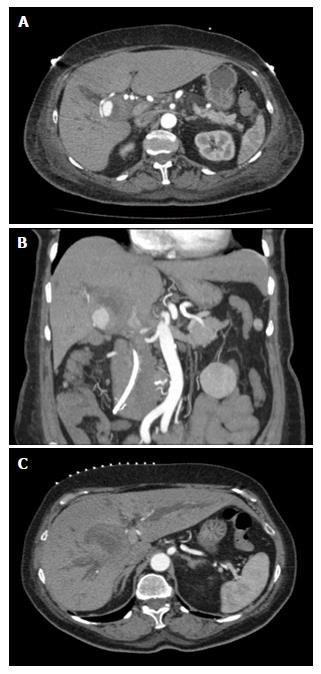

At transfer to our institution, a triphasic computed tomography angiography demonstrated a right branch HAP measuring 2.1 cm, a suspected hematoma measuring 5 cm in diameter (Figure 1A and B) and significant biliary duct dilatation (Figure 1C). Further studies including esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy demonstrated hemobilia with the 2 cm biliary stent protruding into the lumen of the small bowel. Therapeutic strategies to control pseudoaneurysmal bleeding included embolization procedures encompassing percutaneous ultrasound and fluoroscopic guided thrombin injections into the HAP (Figure 2). Multiple sub-centimeter smaller pseudoaneurysms were noted to be extending off of the right hepatic artery. Due to lack of trauma or interventions that could be a likely etiology for pseudoaneurysm, an autoimmune work up, including C-ANCA, P-ANCA, anti-smooth muscle antibodies, double-stranded DNA antibody, anti-smooth muscle antibody, anti-RNP antibody, to establish etiology of these multiple pseudoaneurysms was performed and was largely negative. Rheumatology was consulted and ruled out systemic vasculitides including polyarteritis nodosa (PAN), systemic lupus erythematosus, and cryoglobulinemia. The patient continued to have a complicated long hospital course and even after attempts to alleviate obstructive jaundice with stent procedures, the patient had recurrent episodes of cholangitis with septic shock. Blood cultures demonstrated pan-sensitive Klebsiella pneumoniae likely from biliary source.

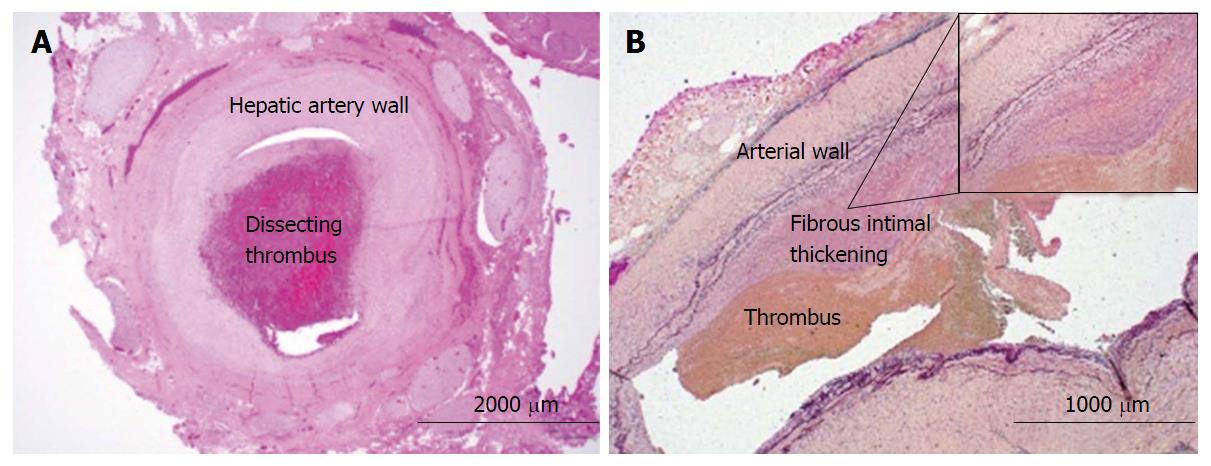

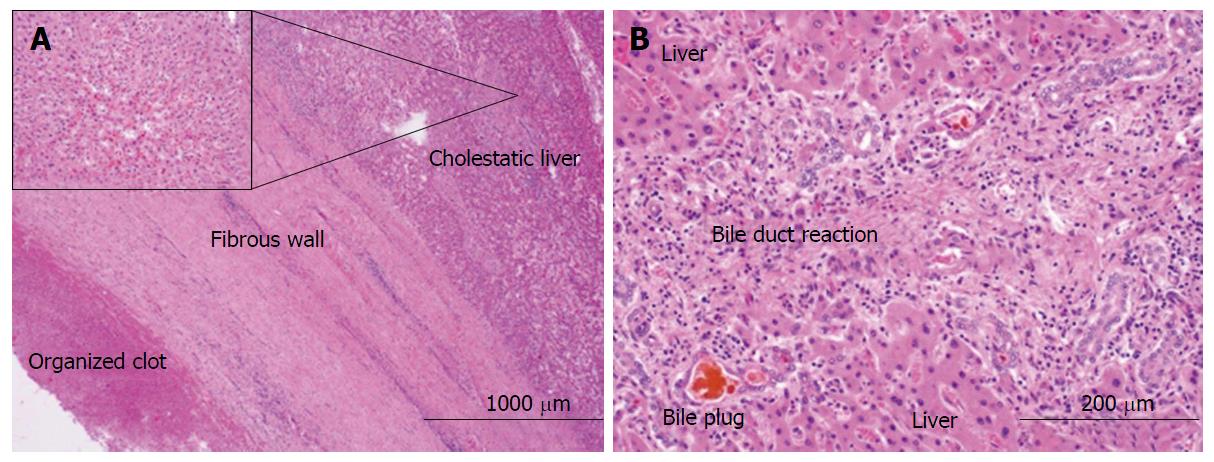

Non-operative strategies included fluoroscopic and ultrasound-guided embolization of re-emergent right HAP with multiple coils, gelfoam, and thrombin. During this procedure it was noted that a portion of thrombosed aneurysm was exerting significant mass effect, effectively occluding multiple right biliary branches and compressing vascular flow in her right portal vein thereby potentially rendering her right lobe ischemic. It was determined that surgical intervention was required for inability to completely address the obstructing nature of this pseudoaneurysm. The patient underwent right hepatic trisegmentectomy with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. Pathology demonstrated the presence of a porta hepatis hematoma (5.0 cm) and organized thrombus dissecting into the hepatic artery wall (Figure 3). Although the liver specimen was negative for malignancy, the liver was microscopically consistent with centrilobular cholestasis (Figure 4A) and bile ductular reaction with bile plugs (Figure 4B) all of which were consistent with chronic biliary obstruction.

The patient was discharged home without any events. She is three years from surgery with no complaints, doing well.

While visceral artery aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms (VAP) may be a rare finding in the general population, with a reported incidence of approximately 0.1%-2%, timely diagnosis is imperative because of the risk of rupture and subsequent mortality[6]. In their retrospective review, Tulsyan et al[7] reported that of the 28 patients found to have VAPs between 1997 and 2005 at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, 39% involved the celiac axis or its branches, 39% arose from the hepatic arteries, 18% from the splenic artery and 4% from the superior mesenteric artery. In this review, the majority of VAPs, including HAPs arose secondary to arterial trauma, intrabdominal or retroperitoneal inflammation or malignancy, and manipulation of the biliary tract[7]. Other non-iatrogenic causes of HAPs include trauma, acute and chronic pancreatitis, arteriosclerosis, PAN, necrotizing vasculitis, infection and hepatocellular carcinoma[2,3,8-10].

Recent increases in the incidence of HAPs have been attributed to a rise in the number of liver transplantations, percutaneous liver and gallbladder interventions and the use of laparoscopic surgery[1,4,9,11]. Advances in imaging techniques have enhanced the detection rate of asymptomatic HAPs[1]. While HAPs may be an incidental finding in an asymptomatic patient, more commonly patients present with abdominal pain, anemia, hemobilia, melena, and can present as life-threatening hemorrhage following rupture[2,8,11]. Although we advocate interventional attempts such as angioembolization or stenting to stop hemorrhage immediately, failures in these attempts or chronic sequel on adjacent structures such as the biliary system and portal vein can require further investigations with possible surgical intervention. We advocate the use of non-invasive assessments, such as CT and/or MRI-MRCP radiographic imaging, to determine the possible etiology of biliary obstruction with then focused therapies toward alleviating the problem. To our knowledge, this is the first presentation of a patient presenting with classic picture of a Klatskin’s tumor, specifically jaundice and pruritis secondary to biliary system compression by HAP that could not be managed with a non-operative approach. This unique presentation and atypical history for HAP initially masked the diagnosis. Despite a thorough diagnostic workup, no identifiable cause was uncovered for this patient’s HAP, which further adds to the complexity and atypical nature of the case.

While HAPs can thrombose and resolve without intervention, the risk of rupture and subsequent hemorrhage are high enough that the general consensus has been in favor of intervention[1,2,4]. At this time, numerous minimally invasive techniques have proven to be successful, including coiling, covered stent exclusion, thrombin injection, gelfoam injection, plug deployment, polyvinyl alcohol injection, and surgical intervention[1,3,4]. The literature has supported all of these techniques as viable options for management of HAPs. Nagaraja et al[12] retrospectively analyzed 29 patients with HAP were successfully managed with angioembolization not surprisingly resulting in more rapid bleeding control, shorter hospital stay, and lower transfusion requirements although a 14% mortality rate in the angioembolization group with no mortality in the surgical group. Currently, minimally invasive management is favored, although indications still exist for surgical intervention. Of note, recurrence of HAPs following embolization has been reported to be significant, and therefore current recommendations involve follow-up imaging with potential need for secondary intervention[9]. In the case of our patient, standard minimally invasive endovascular (HAP) and biliary (obstructive jaundice) management was attempted on several occasions with the use of multiple modalities, but ultimately failed to palliate her symptoms. This specific case presented multiple complications including inability to decompress the right biliary system secondary to mass effect and subsequent ischemia as portal vein. Therefore, surgical intervention, specifically right hepatic trisegmentectomy and bile duct resection, was required to address the biliary outflow obstruction and the inherent risk of rupture and hemorrhage of the HAP itself.

In conclusion, we present a unique case of HAP of unknown etiology, initially presenting with jaundice and pruritus. While the presenting symptoms were inconsistent with the typical presentation of HAPs, it is important to be aware of this as a potential cause of jaundice in addition to the more commonly thought of etiologies. The risk of morbidity and mortality secondary to HAP rupture and subsequent hemorrhage requires immediate identification and intervention. Currently, the literature supports the use of minimally invasive endovascular, endoscopic, and percutaneous approaches in the initial management of HAPs, with the potential need for future open surgical intervention if these techniques are inadequate.

A 65-year-old female with no significant past medical history with a history of painless jaundice and pruritis.

Computed tomography imaging studies revealed a 5 cm dense lesion within the hilar region of the liver and intrahepatic biliary duct dilatation.

Klatskin’s tumor, extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, pancreatic cancer.

Total and direct bilirubin levels were elevated (total bilirubin 24.3 mg/dL, direct dilirubin 18.6 mg/dL), as was her serum alkaline phosphatase (432 U/L), liver transaminases (AST 132 U/L, ALT 148 U/L), and CA 19-9 (891 U/mL). Other pertinent labs included a positive ANA and CEA within the reference range.

Triphasic computed tomography angiography demonstrated a right branch hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm (HAP) measuring 2.1 cm, a suspected hematoma measuring 5 cm in diameter and significant biliary duct dilatation.

Right hepatic trisegmentectomy pathology specimen demonstrated the presence of a porta hepatis hematoma (5.0 cm) and organized thrombus dissecting into the hepatic artery wall, negative for malignancy and microscopically consistent with centrilobular cholestasis and bile ductular reaction with bile plugs all of which were consistent with chronic biliary obstruction.

Complete surgical excision of locally involved right hepatic artery pseuodaneurysm.

HAPs classically arise secondary to trauma or iatrogenic causes and pose a serious risk of exsanguinating hemorrhage and subsequent death. Numerous case reports have been published addressing the occurrence of HAPs subsequent to a variety of interventional procedures including cholecystectomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy, and orthotopic liver transplant. Due to the increased risk of rupture compared with true aneurysms, HAPs have been successfully treated using a variety of interventional methods. Because of the increased morbidity associated with surgery in this setting, surgical management is the final treatment option.

HAPs are “false” aneurysms that do not have the presences of layers of the arterial wall, communicates with the vessel in question and has blood confined by the surrounding tissues.

HAPs are typically managed with a variety of interventional methods such as endovascular embolization, coiling embolization, and arterial stent grafting. Because of the increased morbidity associated with surgery in this setting, surgical management is the final treatment when impairment to adjacent structures such as the bile duct and portal vein cannot be alleviated.

This manuscript presents a rare case of pseudoaneurysm of hepatic artery. The management of the case is informative, and useful for the readers.

P- Reviewer: Palmucci S, Panic N, Tomizawa M S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Lü PH, Zhang XC, Wang LF, Chen ZL, Shi HB. Stent graft in the treatment of pseudoaneurysms of the hepatic arteries. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2013;47:551-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Finley DS, Hinojosa MW, Paya M, Imagawa DK. Hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm: a report of seven cases and a review of the literature. Surg Today. 2005;35:543-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Krokidis ME, Hatzidakis AA. Acute hemobilia after bilioplasty due to hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm: treatment with an ePTFE-covered stent. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2009;32:605-607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fankhauser GT, Stone WM, Naidu SG, Oderich GS, Ricotta JJ, Bjarnason H, Money SR. The minimally invasive management of visceral artery aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:966-970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Julianov A, Georgiev Y. Hepatic artery aneurysm causing obstructive jaundice. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2014;4:294-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hossain A, Reis ED, Dave SP, Kerstein MD, Hollier LH. Visceral artery aneurysms: experience in a tertiary-care center. Am Surg. 2001;67:432-437. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Tulsyan N, Kashyap VS, Greenberg RK, Sarac TP, Clair DG, Pierce G, Ouriel K. The endovascular management of visceral artery aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:276-283; discussion 283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 399] [Cited by in RCA: 425] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Harvey J, Dardik H, Impeduglia T, Woo D, DeBernardis F. Endovascular management of hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm hemorrhage complicating pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:613-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Spiliopoulos S, Sabharwal T, Karnabatidis D, Brountzos E, Katsanos K, Krokidis M, Gkoutzios P, Siablis D, Adam A. Endovascular treatment of visceral aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms: long-term outcomes from a multicenter European study. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2012;35:1315-1325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rencuzogullari A, Okoh AK, Akcam TA, Roach EC, Dalci K, Ulku A. Hemobilia as a result of right hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm rupture: An unusual complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;5:142-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yao CA, Arnell TD. Hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 2010;199:e10-e11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nagaraja R, Govindasamy M, Varma V, Yadav A, Mehta N, Kumaran V, Gupta A, Nundy S. Hepatic artery pseudoaneurysms: a single-center experience. Ann Vasc Surg. 2013;27:743-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |