Published online Aug 28, 2015. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i18.2177

Peer-review started: November 20, 2014

First decision: December 12, 2014

Revised: March 17, 2015

Accepted: July 21, 2015

Article in press: July 23, 2015

Published online: August 28, 2015

Processing time: 282 Days and 20.2 Hours

AIM: To evaluate virological response to telaprevir or boceprevir in combination with pegylated interferon and ribavirin and resistance mutations to NS3/4A inhibitors in hepatitis C virus-human immunodeficiency virus (HCV-HIV) coinfected patients in a real life setting.

METHODS: Patients with HCV genotype 1-HIV coinfection followed in Nice University Hospital internal medicine and infectious diseases departments who initiated treatment including pegylated interferon and ribavirin (PegIFN/RBV) + telaprevir or boceprevir, according to standard treatment protocols, between August 2011 and October 2013 entered this observational study. Patient data were extracted from an electronic database (Nadis®). Liver fibrosis was measured by elastometry (Fibroscan®) with the following cut-off values: F0-F1: < 7.1 kPa, F2: 7.1-9.5 kPa, F3: 9.5-14.5 kPa, F4: ≥ 14.5 kPa. The proportion of patients with sustained virological response (SVR) twelve weeks after completing treatment, frequency and type of adverse events, and NS3/4A protease inhibitor mutations were described.

RESULTS: Forty-one patients were included: 13 (31.7%) patients were HCV-treatment naïve, 22 (53.7%) had advanced liver fibrosis or cirrhosis (Fibroscan stage F3 and F4); none had decompensated cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma; all were receiving antiretroviral treatment, consisting for most them (83%) in either a nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor/protease inhibitor or/integrase inhibitor combination; all patients had undetectable HIV-RNA. One patient was lost to follow-up. SVR was achieved by 52.5% of patients. Five patients experienced virological failure during treatment and four relapsed. Seven discontinued treatment due to adverse events. Main adverse events included severe anemia (88%) and rash (25%). NS3/4A protease mutations were analyzed at baseline and at the time of virological failure in the 9 patients experiencing non-response, breakthrough or relapse. No baseline resistance mutation could predict resistance to HCV protease inhibitor-based treatment.

CONCLUSION: Telaprevir and boceprevir retain their place among potential treatment strategies in HIV-HCV coinfected patients including those with advanced compensated liver disease and who failed previous PegIFN/RBV therapy.

Core tip: Data regarding treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection with triple combination regimen including interferon/ribavirin and a protease inhibitor (telaprevir or boceprevir) among difficult to treat human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-HCV co-infected patients are lacking. Most of the patients included in this single-center observational study had already failed a previous dual treatment course and had severe liver fibrosis, one out of six being both cirrhotic and non-responder to prior therapy. More than one of two patients displayed sustained virological response, suggesting that in low-income countries, telaprevir and boceprevir may retain their place among potential treatment strategies in HIV-HCV coinfected patients.

- Citation: Naqvi A, Giordanengo V, Dunais B, de Salvador-Guillouet F, Perbost I, Durant J, Pugliese P, Joulié A, Roger PM, Rosenthal E. Virological response and resistance mutations to NS3/4A inhibitors in hepatitis C virus-human immunodeficiency virus coinfection. World J Hepatol 2015; 7(18): 2177-2183

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v7/i18/2177.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v7.i18.2177

Therapeutic resources against hepatitis C infection are currently expanding, with remarkable success rates compared to previous results with dual pegylated interferon + ribavirin (PegIFN/RBV) regimens[1]. However some of these new compounds can be associated with considerable costs making them unaffordable in low resource settings or among uninsured patients with low incomes. The situation can be further complicated by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) co-infection, requiring the adjunction of antiretroviral treatment. The availability of multiple approaches for the management of hepatitis C virus (HCV) in HIV-HCV co-infection thus provides a choice of strategies covering a range of costs while offering the patient reasonable chances of therapeutic success.

Most data concerning treatment of HCV infection among HIV-HCV co-infected patients have mainly been based on clinical trials[2-5]. Few have included cirrhotic patients or non-responders to prior HCV therapy with PegIFN/RBV combination, and none to our knowledge have concerned patients who were both cirrhotic and non-responders. We report the virological response to triple combination therapy including IFN/RBV and a protease inhibitor (telaprevir or boceprevir) among a cohort of HIV-HCV genotype 1 co-infected patients followed in a University Hospital.

This was an observational single-center study concerning all genotype 1 HCV-HIV co-infected patients followed in Nice University Hospital internal medicine and infectious diseases departments who initiated treatment including PegIFN/RBV + telaprevir or boceprevir between August 2011 and October 2013 and who were not participating in a clinical trial.

Liver fibrosis was measured by elastometry (Fibroscan®) with the following cut-off values: F0-F1: < 7.1 kPa, F2: 7.1-9.5 kPa, F3: 9.5-14.5 kPa, F4: ≥ 14.5 kPa. Cirrhosis was considered present for values above 14.5 kPa prior to HCV treatment initiation. Virological response to treatment was assessed at 4, 12, 24 and 48 wk. Rapid virological response (RVR) was defined as undetectable HCV-RNA 4 wk after treatment initiation, and sustained virological response (SVR) as undetectable HCV-RNA 12 wk following completion of HCV treatment. Persistently detectable HCV-RNA during treatment was considered as non-response to treatment, while treatment breakthrough concerned patients in whom an initially positive response was followed by renewed detectable HCV-RNA during treatment. Relapse was defined as recurrence of viraemia in patients whose viral load had become undetectable at the end of treatment. Eventual exposure and response to a previous dual PegIFN/RBV regimen was investigated. Patients for whom no HCV viral load was available at 12 wk following dual treatment initiation could not be assessed for prior treatment response. Premature treatment discontinuation of previous dual therapy that was considered related to adverse events was differentiated from virological failure.

Patient data were extracted from an electronic database (Nadis®)[6] and included date of initiation and end of anti-HCV treatment, dose of RBV, peg-interferon, boceprevir and telaprevir, response to previous anti-HCV treatment, HIV-RNA, HCV genotype, HCV-RNA at each stage of follow-up (week 4, 12, 24, 48, and at least 12 wk after completing treatment), antiretroviral treatment, and CD4 T-cell count. The following adverse events were recorded: grade 2 to 4 anemia [hemoglobin (Hb) < 9 g/dL], leucopenia, thrombocytopenia, severe infection, decompensated cirrhosis, rashes, as well as death and cause thereof. erythropoietin (EPO) use and blood transfusions were also reported.

In order to genotype HCV strains, total nucleic acids were extracted from 500 μL of plasma with the NucliSENS® easyMAG® automated platform (BioMerieux). The NS3/4A protease sequence (745 nucleotides) was amplified by reverse-transcriptase nested polymerase chain reaction with protocol and primers described elsewhere[7] (Table 1) and evaluated in a multicenter quality control study[8].

| HCV genotype 1 | Primers | Sequences 5'-3' | H77 location |

| G1F1 | CTB CTS GGR CCR GCC GAT | 3372-3390 | |

| G1R1 | CCA CYT GGW AKS TCT GSG G | 3998-4016 | |

| MarsF3 | ACS GCR GCR TGY GGG GAC AT | 3309-3328 | |

| MarsR2 | GTG CTC TTR CCG CTR CCR GT | 4035-4054 |

Briefly, 40 μL of reaction mixture contained 2X Super Script III One-Step reaction buffer with 0.4 mmol/L dNTP and 5 mmol/L MgSO4, 0.2 μmol/L of each sense and anti-sense primers, 1 μL of Super Script III RT/Platinium Taq High Fidelity and 10 μL of RNA extract. Amplification was performed using Biometra thermocycler: 30 min at 55 °C followed by 2 min at 94 °C, 40 cycles with 30 s at 94 °C, 1 min at 59 °C, 1 min at 68 °C, and a final extension step at 68 °C.

When needed, a nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed involving the inner genotype-specific primers in 40 µL of reaction mixture contained 10X Invitrogen Thermal ace reaction buffer with 0.5 mmol/L dNTP, 0.2 μmol/L of each sense and anti-sense primers and 10 μL of purified product of first step PCR using: 2 min at 95 °C, 35 cycles with 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 59 °C, 1 min at 74 °C, and a final extension step at 74 °C.

PCR-amplified DNA was purified, genotype-specific primers for the inner PCR were used for bidirectional sequencing and automated dideoxynucleotide termination sequencing was performed with BigDye Terminator using a 3130XL Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) then compared to the HCV-H77 reference strain using Sequence Navigator software™ (Applied Biosystems) and Geno2pheno.

Variables at treatment initiation were expressed as frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables, or median (interquartile range) for continuous variables. The rate of treatment response was calculated as the number of patients with undetectable HCV viral load divided by the number of patients with available data on HCV-RNA viral load at the considered visit.

In case of early treatment discontinuation with a detectable HCV viral load, the patient was considered as failing treatment at each subsequent visit up to week 48. In case of early treatment discontinuation with undetectable HCV viral load, the subsequent HCV viral load measurements were used to assess treatment efficacy.

Data analysis was performed using Epi-Info™ version 7 software.

Patient characteristics at treatment initiation are described in Table 2.

| Age: median (IQR) | 51 (48-55) |

| Male gender | 35 (85.4%) |

| Genotype | |

| 1a | 32 (78.0%) |

| 1b | 9 (22.0%) |

| HCV treatment-naïve | 13 (31.7%) |

| Prior HCV-treatment response | |

| Non-responders | 14 (34.1%) |

| Breakthrough | 1 (2.5%) |

| Relapse | 5 (12.2%) |

| Premature treatment discontinuation | 3 (4.9%) |

| Missing data | 5 (14.6%) |

| Log HCV-RNA | 5.8 (5.3-6.1) |

| Fibrosis stage | |

| F0-F1 | 12 (29.3%) |

| F2 | 7 (17.0%) |

| F3 | 5 (12.2%) |

| F4 | 17 (41.5%) |

| CD4 T-cells/mm3: median (IQR) | 540 (441-782) |

| HIV-RNA < 40 copies/mL | 41 (100.0%) |

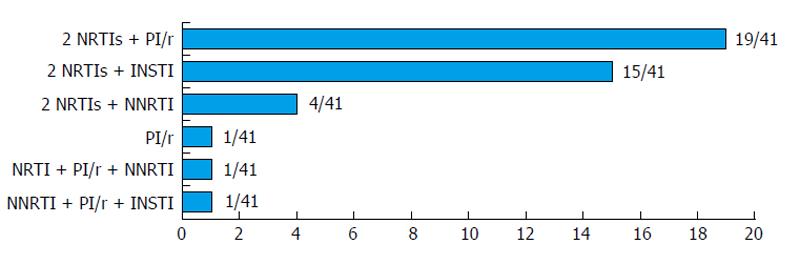

Among 41 patients included in the study, 13/41 (31.7%) were HCV-treatment naïve. Twenty-two patients (53.7%) had advanced liver fibrosis or cirrhosis (Fibroscan stage F3 and F4). None had decompensated cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma. All were receiving antiretroviral treatment, consisting for most patients (83%) in either a nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor/protease inhibitor or/integrase inhibitor combination (Figure 1). All had undetectable HIV-RNA. Thirty-seven patients received telaprevir and 4 were treated with boceprevir in addition to IFN/RBV combination therapy. One patient was lost to follow-up.

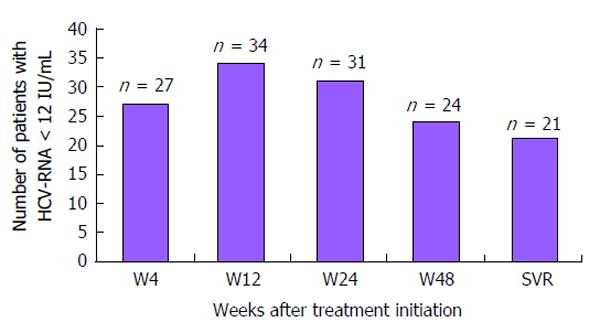

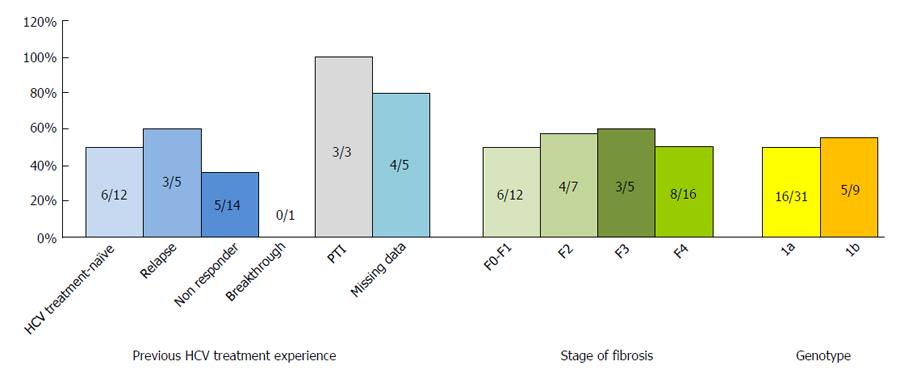

The number of patients with undetectable HCV viral load at different stages of the treatment course is shown in Figure 2. Twenty-seven patients (67.5%) displayed RVR. Response to treatment according to HCV treatment history, stage of fibrosis and HCV genotype is described in Figure 3 among the 40 patients with available follow-up. Twenty-one patients (52.5%) displayed SVR: 6 were treatment-naïve, 5 were partial or non-responders to prior dual agent HCV-treatment regimens, 3 had relapsed, 3 had discontinued treatment prematurely, and response to initial treatment was unspecified for 4 patients. Therapeutic success was observed among all categories except in the patient who had previously experienced virological breakthrough. Among patients with advanced fibrosis (F3-F4), 11/21 (52.4%) exhibited SVR.

Fifteen patients did not complete the treatment course: 5 due to virological failure (3 viral breakthroughs, 2 non- or partial responders), 3 on patient’s decision, and 7 because of adverse events. Eight patients did so within the first 12 wk, three between 12 and 24 wk, and four between 24 and 48 wk. Two of these patients were switched to a sofosbuvir/RBV regimen.

Four patients relapsed: 2 were HCV treatment-naïve with liver fibrosis stages F2 and F3, while the other 2 patients were treatment-experienced with a fibrosis score of F4. Among the seven previously non-responding cirrhotic patients, 2 achieved SVR, 1 relapsed, 1 experienced virological breakthrough, 1 did not respond and 2 discontinued treatment due to adverse events (gingival haemorrhage and psychiatric decompensation).

Among the 15 patients who discontinued treatment prematurely, seven developed the following adverse events: flare-up of porphyria cutanea tarda (1), gingival haemorrhage (1), psychiatric disorder (1), thrombocytopenia (1), fatigue (1), cirrhotic decompensation (1) and acute pancreatitis (1) (Table 3).

| Rash | 10 (25%) |

| Anemia Hb < 13 g/dL (men), < 12 g/dL (women) | 39 (98%) |

| Severe anemia (< 9 g/dL or decrease > 3 g/dL) | 35 (88%) |

| Ribavirin dose decreased | 23 (58%) |

| EPO administration | 23 (58%) |

| Blood transfusion | 2 (5%) |

Thirty five (85%) patients developed severe anemia (Hb < 9 g/dL) requiring either administration of EPO, blood transfusion or both (Table 3).

Pre- and post treatment genotyping of the NS3 protease was performed using standard Sanger sequencing for the nine patients who experienced treatment failure (3 viral breakthroughs, 2 non- or partial responders, and 4 relapses). Their NS3/4A sequences were compared to the HCV-H77 reference strain (reference sequence AF009606) using Sequence Navigator software™ (Applied Biosystems) and were analysed with Geno2pheno HCV. Both methods yielded the same resistance mutations. Details of NS3/4A amino acid resistance mutations are displayed in Table 4. Pre-treatment plasma samples were available for 3 of the 4 relapsing patients, showing an I132V mutation conveying possible resistance to telaprevir. All three were treated with telaprevir and displayed V36A mutations following exposure, conferring 7.4-7.5 fold changes in EC50. The fourth patient, who was the only one to have received boceprevir among patients who failed treatment, had T54S and R155K substitutions following exposure. The non- and partial responders both had no initial mutations but developed V36M and R155K conferring a 62-fold change in antiviral activity.

| Genotype | Previouslytreated | HCV PI | Response totreatment | HIV PI | Pre-treatmentHCV VL | Baseline NS3/4A-mutations | Baselinefold-change | Post-treatmentNS3/4A-mutations | Post-treatmentfold change1 |

| 1a | Yes | Tela | Non-responder | Atazanavir | 5.9 | 0 | V36M, R155K | 62 | |

| 1a | Yes | Tela | Non-responder | 0 | 5.8 | 0 | V36M, R155K | 62 | |

| 1a | Yes | Tela | Breakthrough | Atazanavir | 6.0 | 0 | R155K | 7.4 | |

| 1a | Yes | Tela | Breakthrough | Atazanavir | 6.5 | 0 | V36M | 6.8-10.0 | |

| 1a | No | Tela | Breakthrough | Atazanavir | 6.0 | 0 | V36M, R155K | 62 | |

| 1b | Yes | Tela | Relapse | Atazanavir | 6.4 | I132V | 1.8 | I132V, V36A | 7.4-7.5 |

| 1a | No | Tela | Relapse | 0 | 6.3 | I132V | 1.8 | I132V, V36A | 7.4-7.5 |

| 1b | No | Tela | Relapse | 0 | 4.9 | I132V | 1.8 | I132V, V36A | 7.4-7.5 |

| 1a | NA | Boce | Relapse | Darunavir | NA | NA | NA | T54S, R155K | 8.5 |

No mutations were initially observed among patients who developed virological breakthrough, who all displayed R155K, V36M, or both substitutions after exposure, the latter combination associated with a 62-fold change in EC50.

This observational study assessed the effectiveness of a PegIFN/RBV + HCV-protease inhibitor combination in difficult-to-treat HIV co-infected patients most of whom had already failed a previous dual treatment course and had severe liver fibrosis (54%), one out of six patients being both cirrhotic and non-responder to prior therapy. In spite of such adverse circumstances, among the 40 patients that could be assessed, 52.5% displayed SVR, and one out of three among cirrhotic, non-responders to previous therapy.

Two open-label, single-arm, phase 2 clinical trials (ANRS HC26 TelapreVIH and HC27 BocepreVIH) recently investigated the effectiveness of PegIFN + RBV + protease inhibitor combination in pre-treated patients[4,5]. In the present study performed in a “real-life” setting, the SVR rate was similar to that obtained in the BocepreVIH trial (53%) but lower than that in the TelapreVIH trial (80%) while the proportion of cirrhotic patients (41.5%) was higher (TelapreVIH 23%, BocepreVIH 17%) and patients that were both cirrhotic and non-responders were not included in those trials. A comparison between these two agents was not possible in the present study due to the small number of patients receiving boceprevir. Lacombe et al[9] reported favorable results of triple therapy including telaprevir in 20 HCV genotype 1 mostly cirrhotic HIV-coinfected patients who had failed PegIFN/RBV treatment with 55% success rate at week 24. Overall treatment safety in our patient cohort was comparable to that observed in the above-mentioned clinical trials[4,5]. One out of four patients discontinued treatment due to adverse events or by choice. Anemia was often severe and was the most frequent adverse effect (88%), requiring EPO administration in 60% of patients, without resulting in treatment discontinuation.

In the present study, an analysis of viral populations following treatment failure was performed by sequencing method and sequences were aligned with the NS3/4A sequence from the HCV genotype 1a H77 strain. All nine patients with virological failure displayed a V36M/R155K mutation. This was more frequent for subtype 1a. No amino-acid resistance mutation before treatment was found in these patients using standard Sanger sequencing, so that the emergence of telaprevir-resistant variants could not be predicted from baseline findings. On the other hand, non-response to treatment may be explained by the subtype-specific resistant variants generated by de novo reverse mutation after treatment failure and the relatively higher fitness of these variants, notably R155K[10], or by the presence of minority resistant variants which should be detected by deep-sequencing[11]. In a recent paper, Aherfi et al[12] describe drug concentrations and NS3/4A protease genotyping during therapy with these two agents and report naturally occurring variants with decreased susceptibility to HCV-protease inhibitors (PIs) at baseline in 20% of their cohort of 30 genotype 1 HCV-infected patients; out of 7 treatment failures, six patients displayed amino acid substitutions associated with decreased susceptibility to PIs.

Experience acquired through HIV antiretroviral therapy shows that antiviral resistance, treatment compliance issues and the need for customized treatment regimens require availability of a range of compounds to meet the specific circumstances of each individual patient. Our results suggest that these triple agent regimens including telaprevir or boceprevir should remain part of the HCV treatment arsenal for HIV co-infected patients, even among those with advanced compensated liver disease and who failed PegIFN/RBV therapy, providing patients do not present with baseline predictors of severe complications (platelet count > 100000/μL and serum albumin concentrations > 35 g/L)[13].

Over the last 15 years, the proportion of liver-related deaths in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected adults dramatically increased in developed countries, ranking first as a cause of mortality in HIV-hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected individuals. This data makes treatment of chronic hepatitis C a priority in this population, including very difficult to treat patients.

The addition of telaprevir and boceprevir to dual therapy with pegylated interferon and ribavirin (PegIFN/RBV) strongly improves the odds of achieving a sustained virological response in treatment-naïve HCV genotype 1 patients as well as in prior non-responders and relapsers when compared with standard therapy. Among HIV-HCV co-infected patients, data regarding treatment of HCV infection with triple combination regimen including IFN/RBV and telaprevir or boceprevir is scarce, more particularly in very difficult-to-treat patients with cirrhosis and/or prior null response to PegIFN/RBV therapy.

This observational study showed the effectiveness of a PegIFN/RBV + HCV-protease inhibitor combination in difficult-to-treat HIV coinfected patients, most of whom had already failed a previous dual treatment course and had severe liver fibrosis, one out of six patients being both cirrhotic and non-responder to prior therapy.

The cost of interferon-free regimens with very recent direct-acting antiviral drugs is prohibitive, making them inaccessible in many developing countries. This study suggests that in low-income countries, telaprevir and boceprevir may retain their place among potential treatment strategies in HIV-HCV coinfected patients including those with cirrhosis and/or prior null response to PegIFN/RBV therapy.

Telaprevir and boceprevir are two NS3/4A protease inhibitors. These drugs were the first direct-acting antiviral agents approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of patients infected with HCV genotype 1.

This manuscript presented a clinical observation in evaluating the treatment with telaprevir or boceprevir in combination with pegylated interferon and ribavirin for HIV-HCV coinfected patients. This is a good topic.

P- Reviewer: Chen YD, Elalfy H, He ST S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Chastain CA, Naggie S. Treatment of genotype 1 HCV infection in the HIV coinfected patient in 2014. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2013;10:408-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sulkowski M, Pol S, Mallolas J, Fainboim H, Cooper C, Slim J, Rivero A, Mak C, Thompson S, Howe AY. Boceprevir versus placebo with pegylated interferon alfa-2b and ribavirin for treatment of hepatitis C virus genotype 1 in patients with HIV: a randomised, double-blind, controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:597-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sulkowski MS, Sherman KE, Dieterich DT, Bsharat M, Mahnke L, Rockstroh JK, Gharakhanian S, McCallister S, Henshaw J, Girard PM. Combination therapy with telaprevir for chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection in patients with HIV: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:86-96. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Poizot-Martin I, Bellissant E, Colson P, Renault A, Piroth L, Solas C, Bourlière M, Garraffo R, Halfon P, Molina JM. Boceprevir for previously treated HCV-HIV coinfected patients: the ANRS-HC27 BocepreVIH Trial. Atlanta: 21th CROI 2014; Abstract 659LB. |

| 5. | Cotte L, Braun J, Lascoux-Combe C, Vincent C, Valantin MA, Sogni P, Lacombe K, Neau D, Aumaitre H, Batisse D. Telaprevir for HIV/hepatitis C virus-coinfected patients failing treatment with pegylated interferon/ribavirin (ANRS HC26 TelapreVIH): an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:1768-1776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Pugliese P, Cuzin L, Cabié A, Poizot-Martin I, Allavena C, Duvivier C, El Guedj M, de la Tribonnière X, Valantin MA, Dellamonica P. A large French prospective cohort of HIV-infected patients: the Nadis Cohort. HIV Med. 2009;10:504-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Vallet S, Viron F, Henquell C, Le Guillou-Guillemette H, Lagathu G, Abravanel F, Trimoulet P, Soussan P, Schvoerer E, Rosenberg A. NS3 protease polymorphism and natural resistance to protease inhibitors in French patients infected with HCV genotypes 1-5. Antivir Ther. 2011;16:1093-1102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Vallet S, Larrat S, Laperche S, Le Guillou-Guillemette H, Legrand-Abravanel F, Bouchardeau F, Pivert A, Henquell C, Mirand A, André-Garnier E. Multicenter quality control of hepatitis C virus protease inhibitor resistance genotyping. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:1428-1433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lacombe K, Valin N, Stitou H, Gozlan J, Thibault V, Boyd A, Poirier JM, Meynard JL, Valantin MA, Bottero J. Efficacy and tolerance of telaprevir in HIV-hepatitis C virus genotype 1-coinfected patients failing previous antihepatitis C virus therapy: 24-week results. AIDS. 2013;27:1356-1359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sullivan JC, De Meyer S, Bartels DJ, Dierynck I, Zhang EZ, Spanks J, Tigges AM, Ghys A, Dorrian J, Adda N. Evolution of treatment-emergent resistant variants in telaprevir phase 3 clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:221-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Akuta N, Suzuki F, Seko Y, Kawamura Y, Sezaki H, Suzuki Y, Hosaka T, Kobayashi M, Hara T, Kobayashi M. Emergence of telaprevir-resistant variants detected by ultra-deep sequencing after triple therapy in patients infected with HCV genotype 1. J Med Virol. 2013;85:1028-1036. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Aherfi S, Solas C, Motte A, Moreau J, Borentain P, Mokhtari S, Botta-Fridlund D, Dhiver C, Portal I, Ruiz JM. Hepatitis C virus NS3 protease genotyping and drug concentration determination during triple therapy with telaprevir or boceprevir for chronic infection with genotype 1 viruses, southeastern France. J Med Virol. 2014;86:1868-1876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hézode C, Fontaine H, Dorival C, Larrey D, Zoulim F, Canva V, de Ledinghen V, Poynard T, Samuel D, Bourlière M. Triple therapy in treatment-experienced patients with HCV-cirrhosis in a multicentre cohort of the French Early Access Programme (ANRS CO20-CUPIC) - NCT01514890. J Hepatol. 2013;59:434-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 30.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |