Published online Sep 27, 2010. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v2.i9.362

Revised: September 5, 2010

Accepted: September 12, 2010

Published online: September 27, 2010

Tertiary syphilis, especially in cases involving visceral gummatous disease, can be confused with cancer of the solid organs. We report a case of tertiary hepatic syphilis that manifested with intrahepatic masses in a patient who had an underlying primary peritoneal serous carcinoma (PPSC). The patient was diagnosed with PPSC and achieved a complete remission of PPSC following six cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy. Two hepatic nodules developed during the follow-up period and were initially labeled as hepatic metastases from the underlying PPSC, based on radiological findings. A resection of hepatic nodules was performed for therapeutic and diagnostic purposes, because there were no other metastatic foci except in the liver. Unexpectedly, serology and histology confirmed tertiary syphilis. This rare case emphasizes the importance of including tertiary syphilis in the differential diagnosis of a space-occupying lesion, even with an existing diagnosis of underlying cancer.

- Citation: Shim HJ. Tertiary syphilis mimicking hepatic metastases of underlying primary peritoneal serous carcinoma. World J Hepatol 2010; 2(9): 362-366

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v2/i9/362.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v2.i9.362

Syphilis is a unique infectious disease that presents with variable clinical manifestations[1]. Although the incidence of the disease has decreased, syphilis often presents a diagnostic dilemma, because of its variable clinical features[2]. It progresses, if untreated, through primary, secondary, and tertiary stages. In particular, tertiary syphilis often mimics cancer, because it frequently presents as a space-occupying lesion in visceral organs[3-7].

I report a rare case of hepatic nodules in a patient who had a clinical history of primary peritoneal serous carcinoma (PPSC), which was initially diagnosed as hepatic metastases of PPSC by radiological findings, but was confirmed to be tertiary hepatic syphilis by serological tests and histological findings.

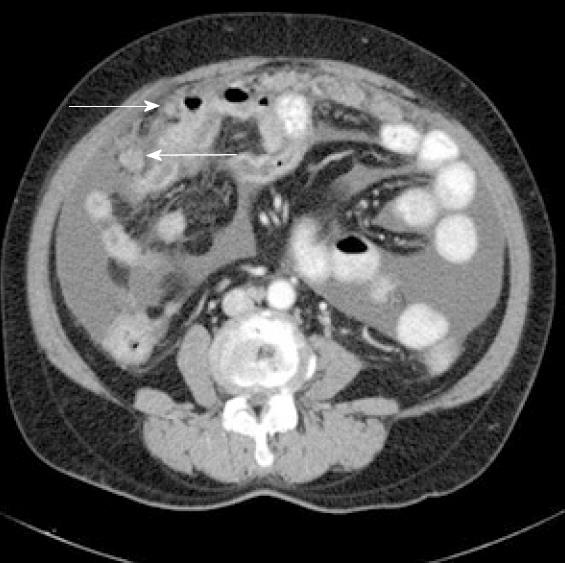

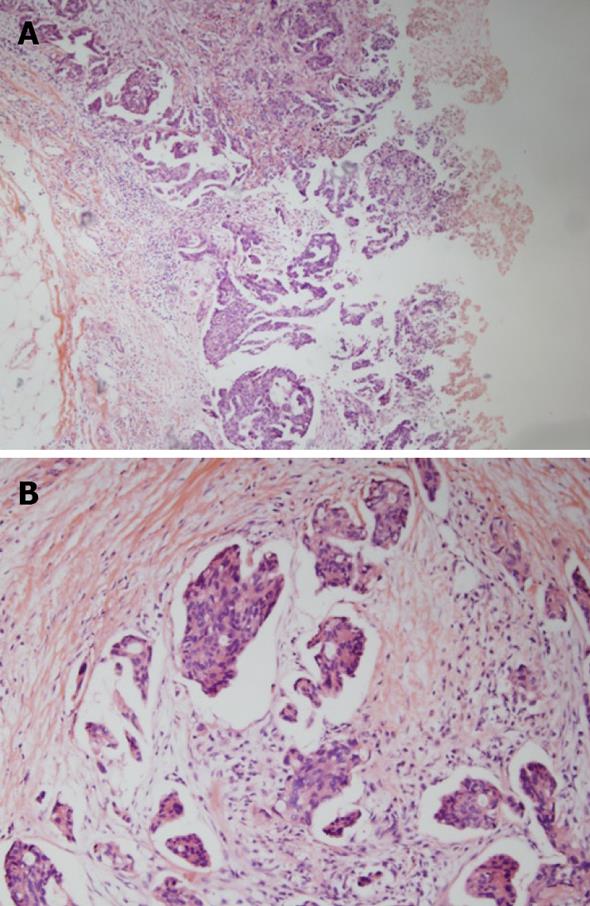

A 65-year-old woman presented at our hospital with a 2-mo history of intermittent abdominal pain and distension. Past medical and familial histories were unremarkable. Physical examination showed abdominal distension and diffuse abdominal tenderness. Her Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status score was 1. Abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) showed a small volume of ascites and several peritoneal nodules without mass-like lesions in the visceral organs (Figure 1). Cytological examination of the ascites suggested metastatic adenocarcinoma. We evaluated possible primary cancer origins; however, no primary site of malignancy was identified. The patient’s CA-125 level was elevated, to 485 U/mL (normal range up to 35 U/mL), but all other evaluated tumor markers were negative. A laparoscopic biopsy of the peritoneum showed a papillary type of adenocarcinoma (Figure 2). Thus, the patient was finally diagnosed with PPSC and started on platinum-based combination chemotherapy. The patient achieved a complete response after six cycles of chemotherapy. Additionally, her CA-125 level returned to normal, at less than 5U/mL.

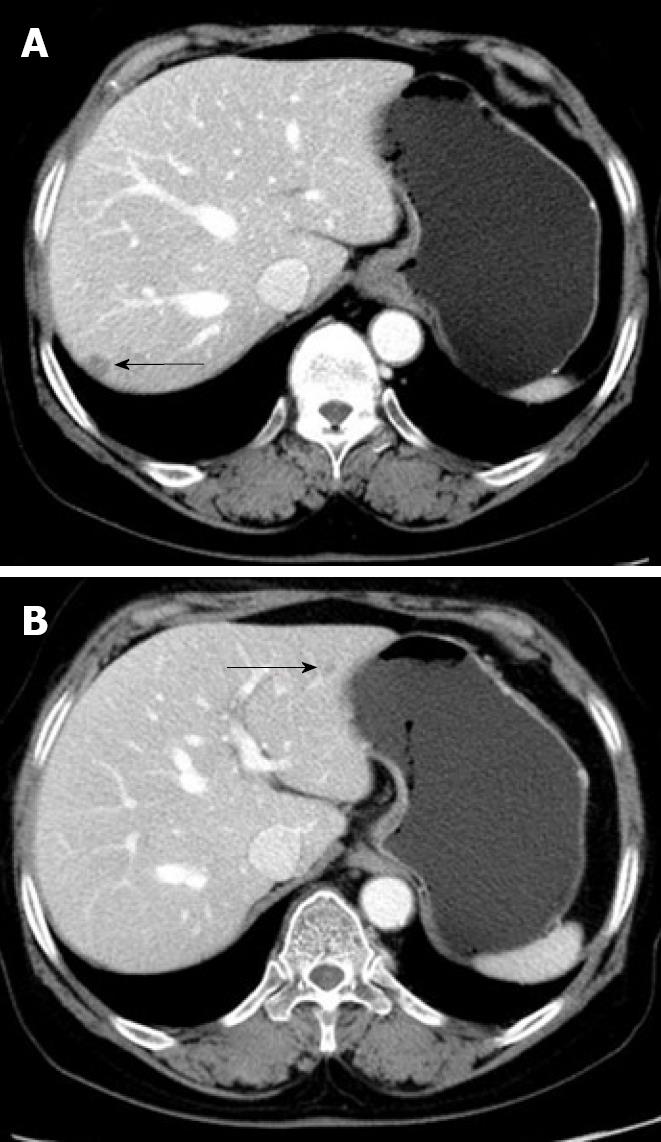

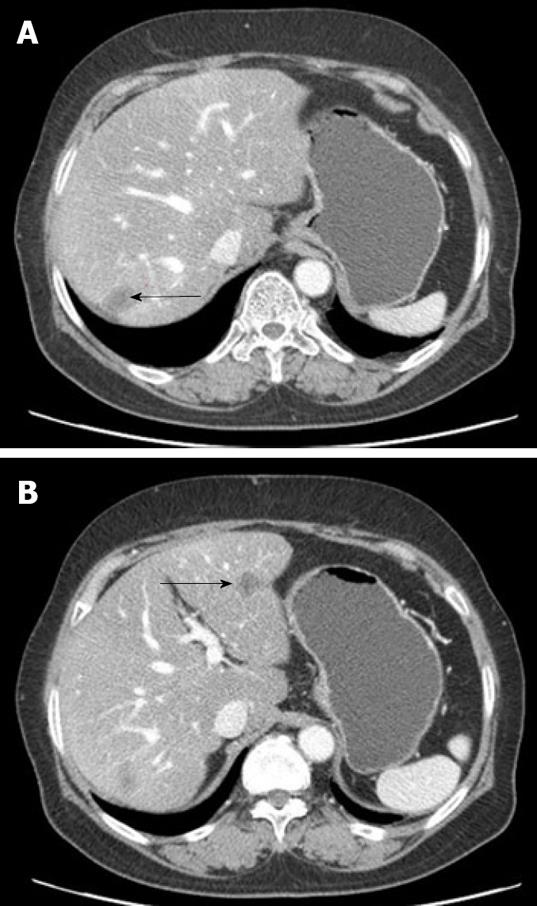

Nine mo after the last round of chemotherapy, a follow-up abdominal CT with peripheral contrast enhancement showed two low-attenuation nodules in the liver. The subsequent liver magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings also suggested liver metastasis (Figure 3). Laboratory tests showed elevated serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST, 260 IU/L) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT, 191 IU/L), but her CA-125 level remained within normal limits. Although PPSC recurrence was suspected, based on the clinical and radiological findings, there were no other suspicious lesions except for those found in the liver. For therapeutic and diagnostic purposes, a wedge resection was performed on the two 1-cm diameter masses in the liver.

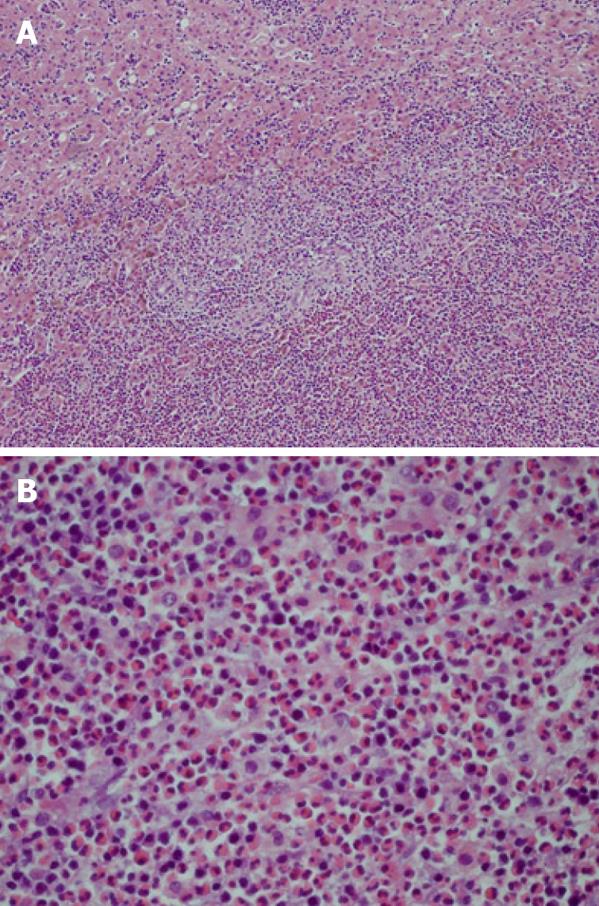

Histologically, the specimens showed central necrosis, granulation tissue, and peripheral fibrosis with eosinophilic infiltration, but no evidence of malignancy (Figure 4). Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), methenamine silver, and Warthin-Starry stains were all negative. The patient had no history of a chronic inflammatory disease, including syphilis. Evaluation for the presence of other indolent diseases which might cause granulation with necrosis in the liver, such as tuberculosis, was performed. The results of these tests, including a chest X-ray, sputum examinations for tuberculosis (staining for acid-fast bacilli and culture for Mycobacterium tuberculosis), and the Mantoux test were all negative. The patient was unavailable for further clinical follow-up and additional evaluations following surgery.

Five years after surgery, the patient returned to the hospital for follow-up without symptoms. Similar to her prior presentation, liver enzymes were elevated (AST 640 IU/L, ALT 380 IU/L), but other laboratory findings, including CA-125, were within normal limits. The patient had no hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, or abdominal distension. However, the follow-up abdominal CT and liver MRI showed recurrent lesions around the previous operative sites (Figure 5). When another hepatic resection was performed to confirm the diagnosis, the histological findings were similar to the previous hepatic biopsy findings: the presence of a necrotic inflammatory mass with granulation tissue components, but without malignant cells (Figure 6). Microbiological assessments, including Gram stain, tissue culture, and fungal and mycobacterial studies, were all negative. PAS, methenamine silver, and Warthin-Starry stains were also negative. Serological testing for syphilis was also performed, which yielded the following positive results: VDRL, 1:16; Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay (TPHA), 1:80; and positive fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS). Assessment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) serology yielded negative results. Based on these serologic and histological findings, the patient was diagnosed as having tertiary syphilis with hepatic gumma. Liver enzyme test results returned to normal following treatment with penicillin. The patient currently has no evidence of tumor or syphilis recurrence.

Syphilis, a chronic infectious disease caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum, is usually acquired by sexual contact with another infected individual. The tertiary disease stage appears in approximately one-third of untreated cases. Any organ of the body may be involved, but the most common types of tertiary disease are gumma, cardiovascular syphilis, and neurosyphilis[1].

Liver involvement caused by syphilis may occur in the secondary and tertiary disease stages. Secondary hepatic syphilis usually begins within a few weeks to a few months after the initial chancre in about 0.2% of syphilis cases, typically manifesting as mild clinical hepatitis[8]. During the tertiary period, localized gumma may develop in the liver and usually develop 1-10 years after the initial infection[1].

Based on autopsy reports, the incidence of tertiary hepatic syphilis (hepatic gummas) ranges from 0.3% to 16%[3,9]. Hepatic gummas were once the most common form of visceral syphilis and often manifested as hepatosplenomegaly, anemia, and occasionally as fever and jaundice. There are usually multiple gumma lesions of variable size distributed throughout both lobes of the liver[3].

Histologically, the gumma is a granuloma[1]. Syphilitic gummas have central necrosis, similar to caseous necrosis. Other histological features of these gummas include a dense fibrous wall with adjacent chronic lymphocytic, plasmacytic and histiocytic inflammation or some epithelioid granulomas with giant cells. It is difficult to identify a causative organism in the tissue of these gummatous lesions. Spirochete identification has been reported in only 0%-5% of cases with tertiary hepatic syphilis[3].

Radiologically, a CT scan typically shows low-attenuated lesions with slight peripheral enhancement and rare calcifications[10-11]. With this radiological finding, the differential diagnosis of tertiary hepatic syphilis should also include abscess, as well as primary and metastatic tumors.

Tertiary syphilis is treated with benzathine-penicillin G. Symptoms disappear and serologic tests normalize within a few weeks or months after treatment. In addition to histological findings and positive blood syphilis reactions (VDRL and FTA), therapeutic response has been used as confirmation of tertiary syphilis[3].

PPSC has been used to describe serous carcinoma of the peritoneum. PPSC is characterized by peritoneal carcinomatosis with pathological and clinical features that are similar to ovarian cancer, although there is no ovarian primary tumor[12-13]. The optimal treatment for PPSC is initial cytoreductive surgery, if indicated, followed by platinum/paclitaxel combination chemotherapy, similar to patients with ovarian cancer[13].

CA-125 is elevated in 80%-85% of women with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer[14]. Follow-up measurement of the patient’s CA-125 level is recommended if the level was initially elevated. Hepatic metastasis of primary ovarian cancer eventually occurs in nearly one-half of patients[15]. With the current patient, the results of imaging studies were highly suggestive of metastatic hepatic carcinoma. However, her CA-125 levels were within normal limits. This clinical discordance supported the need to resect the hepatic nodules for both diagnostic purposes and treatment. The pathological findings were not compatible with a hepatic metastasis from PPSC. Instead, tertiary hepatic syphilis was diagnosed, which is a readily treatable disease.

Cases involving gummas are increasingly infrequent, due to the availability of penicillin treatment. However, gummas most often elicit medical attention as space-occupying lesions in the liver, stomach, brain and oropharynx, mimicking neoplastic conditions[3-7]. Differentiation of a cancer from a gumma is essential to facilitate appropriate patient management.

In conclusion, this case illustrates several important points. Firstly, this is the first report on tertiary hepatic syphilis mimicking hepatic metastases in a patient who showed a complete response after treatment for an underlying PPSC. Although syphilis has decreased in incidence, tertiary hepatic syphilis should still be considered in the differential diagnosis of space-occupying lesions of the liver. Additionally, histological diagnosis is critical, especially in patients treated with a curative aim and with any discordance between the clinical and imaging diagnoses.

Peer reviewers: Emmanouil Sinakos, MD, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 11A, Perdika Str, Pilea 55535, Greece; Kelvin Kwok-Chai Ng, PhD, Department of Surgery, Queen Mary Hospital, 102 Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong, China

S- Editor Zhang HN L- Editor Hughes D E- Editor Liu N

| 1. | Hook EW 3rd. Syphilis. Cecil Medicine, 23rd Edition. Philadelphia: Saunder Elsevier 2008; 2280-2288. |

| 2. | Da Ros CT, Schmitt Cda S. Global epidemiology of sexually transmitted diseases. Asian J Androl. 2008;10:110-114. |

| 3. | Maincent G, Labadie H, Fabre M, Novello P, Derghal K, Patriarche C, Licht H. Tertiary hepatic syphilis. A treatable cause of multinodular liver. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:447-450. |

| 4. | Ances BM, Danish SF, Kolson DL, Judy KD, Liebeskind DS. Cerebral gumma mimicking glioblastoma multiforme. Neurocrit Care. 2005;2:300-302. |

| 5. | Choi YL, Han JJ, Lee da K, Cho MH, Kwon GY, Ko YH, Park CK, Ahn G. Gastric syphilis mimicking adenocarcinoma: a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2006;21:559-562. |

| 6. | Tamura S, Takimoto Y, Hoshida Y, Okada K, Yoshimura M, Uji K, Yoshida A, Miki H, Itoh M. A case of primary oropharyngeal and gastric syphilis mimicking oropharyngeal cancer. Endoscopy. 2008;40 Suppl 2:E235-E236. |

| 7. | Darwish BS, Fowler A, Ong M, Swaminothan A, Abraszko R. Intracranial syphilitic gumma resembling malignant brain tumour. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15:308-310. |

| 8. | Hahn R. Syphilis of the liver. Am J Syphilis. 1943;27:529-562. |

| 9. | Kellock IA, Laird SM. Late hepatic syphilis. Br J Vener Dis. 1956;32:236-241. |

| 10. | Shapiro MP, Gale ME. Tertiary syphilis of the liver: CT appearance. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1987;11:546-547. |

| 11. | Peeters L, Van Vaerenbergh W, Van der Perre C, Lagrange W, Verbeke M. Tertiary syphilis presenting as hepatic bull’s eye lesions. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2005;68:435-439. |

| 12. | Eltabbakh GH, Piver MS. Extraovarian primary peritoneal carcinoma. Oncology (Williston Park). 1998;12:813-819; discussion 820, 825-816. |

| 13. | Bhuyan P, Mahapatra S, Mahapatra S, Sethy S, Parida P, Satpathy S. Extraovarian primary peritoneal papillary serous carcinoma. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;281:561-564. |

| 14. | Maggino T, Sopracordevole F, Matarese M, Di Pasquale C, Tambuscio G. CA-125 serum level in the diagnosis of pelvic masses: comparison with other methods. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1987;8:590-595. |