Published online Mar 27, 2023. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v15.i3.431

Peer-review started: December 7, 2022

First decision: December 19, 2022

Revised: February 3, 2023

Accepted: March 9, 2023

Article in press: March 9, 2023

Published online: March 27, 2023

Processing time: 105 Days and 7.5 Hours

Alcohol use disorder is a prevalent disease in the United States. It is a well-demonstrated cause of recurrent and long-standing liver and pancreatic injury which can lead to alcohol-related liver cirrhosis (ALC) and chronic pancreatitis (ACP). ALC and ACP are associated with significant healthcare utilization, cost burden, and mortality. The prevalence of coexistent disease (CD) ranges widely in the literature and the intersection between ALC and ACP is inconsistently characterized. As such, the clinical profile of coexistent ALC and ACP remains poorly understood. We hypothesized that patients with CD have a worse phenotype when compared to single organ disease.

To compare the clinical profile and outcomes of patients with CD from those with ALC or ACP Only.

In this retrospective comparative analysis, we reviewed international classification of disease 9/10 codes and electronic health records of adult patients with verified ALC Only (n = 135), ACP Only (n = 87), and CD (n = 133) who received care at UPMC Presbyterian-Shadyside Hospital. ALC was defined by histology, imaging or clinical evidence of cirrhosis or hepatic decompensation. ACP was defined by imaging findings of pancreatic calcifications, moderate-severe pancreatic duct dilatation, irregularity or atrophy. We compared demographics, pertinent clinical variables, healthcare utilization, and mortality for patients with CD with those who had single organ disease.

Compared to CD or ACP Only, patients with ALC Only were more likely to be older, Caucasian, have higher body mass index, and Hepatitis B or C infection. CD patients (vs ALC Only) were less likely to have imaging evidence of cirrhosis and portal hypertension despite possessing similar MELD-Na and Child C scores at the most recent contact. CD patients (vs ACP Only) were less likely to have acute or recurrent acute pancreatitis, diabetes mellitus, insulin use, oral pancreatic enzyme therapy, and need for endoscopic therapy or pancreatic surgery. The number of hospitalizations in patients with CD were similar to ACP Only but significantly higher than ALC Only. The overall mortality in patients with CD was similar to ALC Only but trended to be higher than ACP Only (P = 0.10).

CD does not have a worse phenotype compared with single organ disease. The dominant phenotype in CD is similar to ALC Only which should be the focus in longitudinal follow-up.

Core Tip: Patients with coexistent alcohol-related cirrhosis and alcohol-related chronic pancreatitis do not have a worse phenotype when compared with single organ disease patients. The dominant phenotype in patients with coexistent disease (CD) in terms of overall survival and markers of advanced liver disease was similar to patients with Alcohol-related Cirrhosis Only. Coexistent disease patients also had lower prevalence of disease-related manifestations when compared with those who had single organ disease. Patients with CD may not need to be monitored at a higher degree, but the primary focus for longitudinal follow-up should be on alcohol-related cirrhosis.

- Citation: Lu M, Sun Y, Feldman R, Saul M, Althouse A, Arteel G, Yadav D. Coexistent alcohol-related cirrhosis and chronic pancreatitis have a comparable phenotype to either disease alone: A comparative retrospective analysis. World J Hepatol 2023; 15(3): 431-440

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v15/i3/431.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v15.i3.431

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a disease affecting over 14 million adults in the United States[1]. Long-standing alcohol use is a well-established cause of liver and pancreatic injury that can culminate in alcohol-related liver cirrhosis (ALC) and alcohol-related chronic pancreatitis (ACP)[2,3]. The complications of ALC and ACP are major causes of morbidity and mortality associated with alcohol misuse[4-6].

The liver and pancreas are developmentally related and share a number of functional similarities; they also exhibit common features of alcohol-induced injury. The quantity of alcohol misuse is the primary risk factor for developing both diseases and leads to the metabolic stress and low-grade inflammation that stimulates maladaptive fibrotic changes[7]. Susceptibility for developing ALC and/or ACP also relates to non-modifiable risk factors such as race, genetics, and environment[8-11]. ALC-related complications range from ascites and portosystemic encephalopathy to hepatorenal syndrome and hepatocellular carcinoma, and it is estimated that alcohol use accounts for 20%-36% of cirrhosis cases[12-14]. The rate of cirrhosis-related hospitalizations and annual costs have been increasing[15,16]. Comparably, the long-standing inflammatory state in chronic pancreatitis (CP) results in irreversible parenchymal destruction and dysfunction. ACP often begins with an index acute pancreatitis event that progresses to CP as dictated by the severity and number of recurrent episodes of acute pancreatitis[17]. Commonly attributed to alcohol consumption in the North American population, complications from CP include chronic pain, exocrine/endocrine insufficiency, and pancreatic adenocarcinoma[18-20] and poor quality of life[21].

Although ALC and ACP have been well-studied in isolation, patients with overlap of ALC and ACP (i.e., Coexistent Disease) is inconsistently characterized in the literature. Some studies have failed to demonstrate any association between ALC and ACP[22,23] while others suggest interconnectivity between alcohol-related liver and pancreas disease. For instance, alcohol-related liver disease can lead to pancreatic exocrine insufficiency and accumulation of fatty acid ethyl esters which contributes to further progression of alcohol-related liver[24] and pancreas disease[25], while ACP can cause and exacerbate portal hypertension which worsens the complications of liver disease[26]. Furthermore, emerging data from the United States in recent years suggests that coexistent disease (CD) represent only a small fraction of patients with AUD. Although estimates of prevalence of CD in the literature range widely from 0%-75%, a meta-analysis performed by our group revealed a pooled prevalence of ACP in ALC and ALC in ACP to be 16.2% and 21.5% respectively[27].

To date, published studies have yet to define the clinical profile of patients with CD and its differences from single-organ disease. We hypothesized that patients with CD will have a more advanced phenotype and worse outcomes when compared with patients who have single organ (ALC Only or ACP Only) disease. To test this hypothesis, we performed a detailed comparative analysis of well-characterized patients with ACP Only, ALC Only, and CD who received care in a large healthcare system cohort.

The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh’s Institutional Review Board. The patient pool consisted of those who were aged ≥ 18 years, had one or more inpatient, emergency room, and outpatient encounters at any UPMC facility from January 1, 2006 to December 31, 2017 with international classifications of diseases (ICD) versions 9 and/or 10 codes for AUD, alcohol-related liver disease or pancreatitis (Supplementary material), had 12 or more months of contact with the UPMC system, and received care at UPMC Presbyterian-Shadyside campus at some time during their care at UPMC[28]. Among these patients, we randomly identified a subset who received a diagnosis of ALC Only (n = 202), ACP Only (n = 200) and both ALC and ACP (n = 200). Unlike ALC for which etiology-specific codes are routinely used in clinical practice, ICD-9 classification for pancreatitis did not include etiology-specific codes, which became available with the ICD-10 coding system. In our dataset, as only a small portion of patients received an ICD-10 diagnosis of ACP, we identified patients as ACP by the diagnosis of AUD at any time in addition to CP, as was described previously[28].

Analysis and review of the Electronic Health Records of the 602 randomly identified patients was performed by 2 authors (ML, YS) under the supervision of the senior author using pre-defined criteria to verify the diagnosis of cirrhosis and CP. Cirrhosis was defined by histologic findings, imaging evidence of cirrhosis or portal hypertension, or clinical signs of hepatic decompensation. CP was defined by imaging findings of pancreatic calcifications, moderate-severe pancreatic ductal dilation, pancreatic ductal stricture or gland atrophy. To ensure that patients with ALC Only did not have any clinical pancreatic disease, we excluded patients with a verified diagnosis of ALC who had prior acute or recurrent acute pancreatitis. Similarly, among patients with verified ACP Only, we excluded those who had prior alcohol-related hepatitis. Patients with a verified diagnosis of ALC Only, ACP Only and both ALC and ACP (CD) formed the study population.

For each patient with a verified diagnosis, we reviewed the Electronic Health Records to retrieve detailed information on demographics, alcohol and tobacco use, pertinent clinical information for ALC and ACP, healthcare utilization and overall survival until March 3, 2021. Information relevant to liver disease included details of verification criteria fulfilled, clinical features of portal hypertension, hepatic decompensation, history of alcohol-related hepatitis, Child-Pugh and MELD scores, need for liver transplantation, and treatments received. For CP, in addition to the verification criteria fulfilled, information was collected on clinical features of CP, laboratory tests, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan results, and treatments for CP or its complications.

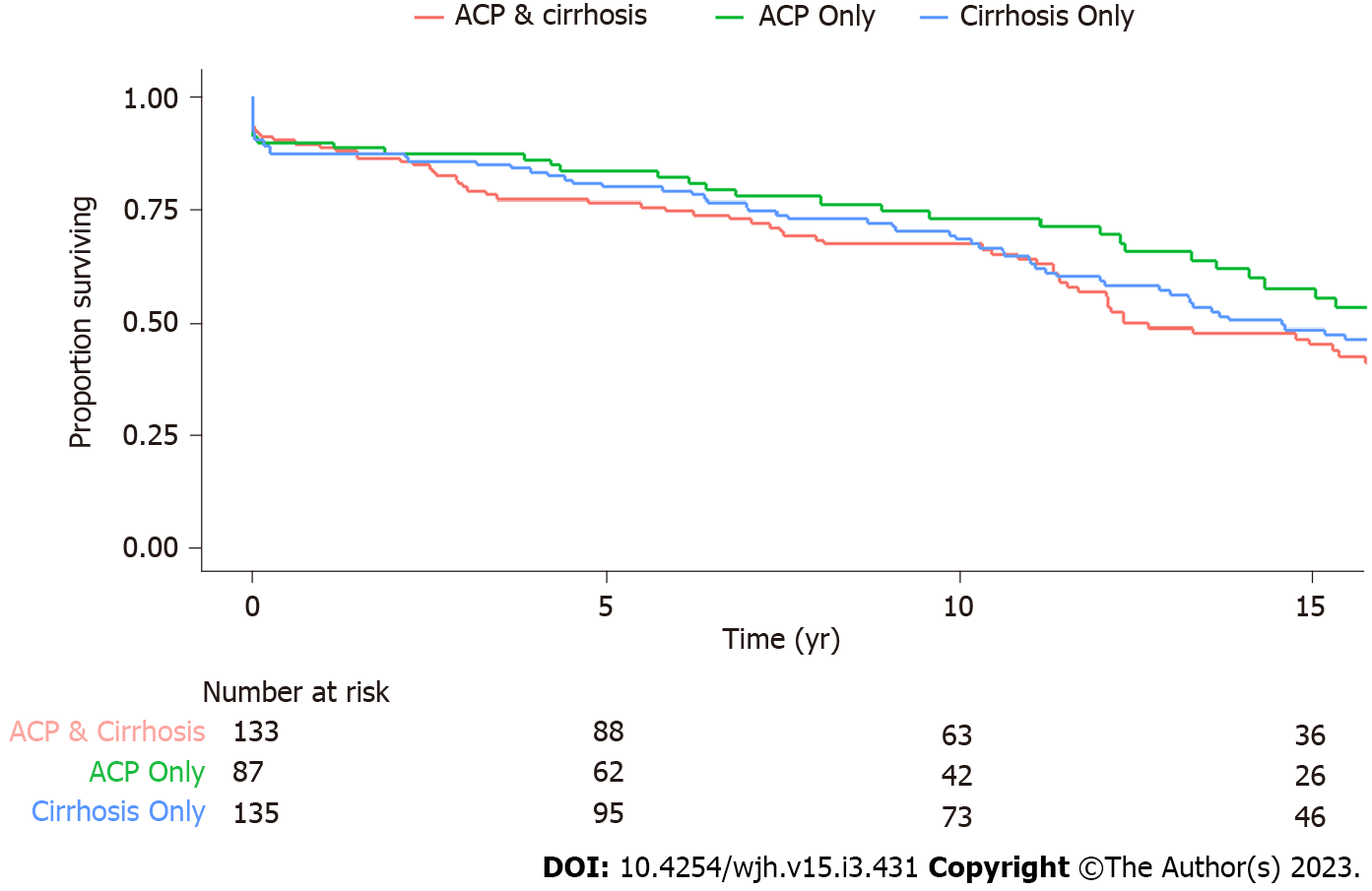

We report demographic and disease-specific information for each of the three groups. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range), and categorical variables were reported as n (%). Statistical comparisons were made using t-test and Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Survival from time of first diagnosis is reported using the Kaplan-Meier method. Cox proportional-hazards models are used to report the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for patients with ALC Only vs ACP Only and CD vs ACP Only while adjusting for age at diagnosis, sex, and race. All statistical analyses were performed using R, version 4.1.3 by biomedical statisticians (RF, AA).

The final study population consisted of 355 patients with verified diagnosis - 135 with ALC Only, 87 with ACP Only, and 133 with CD. Select characteristics of these patients are presented in Table 1. When compared with CD, patients with ALC Only were older at the time of study entry, had higher body mass index, were more likely to be Caucasian and more likely to have Hepatitis B and C infections. While roughly one-thirds of patients with CD or ALC Only were female, only 23% of ACP patients were female. The median duration of contact was greater than 10 years and was comparable between groups. The median number of non-elective hospital admissions for CD and ACP Only were comparable and significantly greater than patients with ALC Only. During follow-up, the number of patients who died in the CD, ALC Only, and ACP Only group was 80 (60%), 82 (61%), and 36 (41%), respectively. Survival analysis using Cox-regression after controlling for age, sex and race (Figure 1) demonstrated that the survival between ALC Only and ACP Only was similar (HR 1.22, 95%CI 0.82-1.82, P = 0.32), while there is a trend towards lower survival in patients with CD when compared to ACP Only (HR 1.40, 95%CI 0.94-2.09, P = 0.10).

| CD (n = 133) | ALC only (n = 135) | ACP only (n = 87) | P value (CD vs ALC only) | P valve (CD vs ACP only) | |

| Age (at study entry), yr – mean ± SD | 51.7 ± 12.0 | 54.6 ± 9.8 | 51.0 ± 12.3 | 0.029 | 0.684 |

| Female | 49 (38) | 42 (31) | 20 (23) | 0.322 | 0.03 |

| Race | 0.015 | 0.52 | |||

| Caucasian | 97 (73) | 113 (84) | 61 (70) | ||

| Black | 30 (23) | 22 (16) | 24 (28) | ||

| Other | 6 (5) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | ||

| Body mass indexa – mean ± SD | 24.2 ± 7.0 | 27.8 ± 6.5 | 23.3 ± 5.4 | < 0.001 | 0.281 |

| Tobacco use | 117 (88) | 109 (81) | 81 (93) | 0.104 | 0.127 |

| Smoking (one or more packs per day | 31 (23) | 23 (17) | 24 (28) | 0.29 | 0.392 |

| Alcohol use (duration), yr – mean ± SD | 26.7 ± 16.0 | 29.4 ± 13.8 | 23 ± 18.4 | 0.595 | 0.762 |

| Hepatitis B Infection | 7 (5) | 17 (13) | 2 (2) | 0.036 | 0.278 |

| Hepatitis C Infection | 31 (23) | 58 (43) | 14 (16) | 0.001 | 0.194 |

| Non-Elective Hospital Admissionsb – median (IQR) | 4 (1 - 12) | 3 (0 - 7) | 4 (1 - 8) | 0.007 | 0.57 |

| Duration of observation, yr – mean ± SD | 10.8 ± 7.9 | 12.4 ± 7.6 | 11.8 ± 7.6 | 0.107 | 0.36 |

Select disease-specific characteristics of patients with CD and ALC Only are shown in Table 2. Patients with ALC Only underwent liver biopsy more often than those with Coexistent disease (33.3% vs 16.5%, P = 0.002). Patients with ALC Only were more likely to have radiographic evidence of cirrhosis (93% vs 76%, P ≤ 0.001) and portal hypertension (74% vs 59%, P = 0.006) on imaging. Although MELD and Child-Pugh scores at most recent contact were similar among patients with CD and ALC Only, some specific clinical features differed between the two groups. Specifically, while patients with CD were more likely to have a history of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, those with ALC Only were more likely to have esophageal varices, need for variceal banding, treatment with beta blockers, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Other features of decompensated liver disease (e.g., ascites) or treatments (e.g., TIPS) were similar between the two groups.

| Characteristics present | CD (n = 133) | ALC only (n = 135) | P value |

| Verification criteria fulfilled | |||

| Liver biopsy performed | 22 (17) | 45 (33) | 0.002 |

| Cirrhosis on biopsy | 13 (59) | 22 (49) | 0.349 |

| Cirrhosis on imagingb | 101 (76) | 126 (93) | < 0.001 |

| Portal hypertension features on imaging | 78 (59) | 100 (74) | 0.006 |

| Alcohol-Related hepatitis | 48 (36) | 34 (25) | 0.052 |

| MELD scorea | 19.3 ± 8.98 | 18.7 ± 8.89 | 0.614 |

| Child-Pugh scorea | 0.69 | ||

| A | 41 (31) | 48 (36) | |

| B | 49 (39) | 48 (36) | |

| C | 43 (32) | 39 (29) | |

| Complications of portal hypertension | |||

| Esophageal varices on EGD | 46 (35) | 68 (50) | < 0.001 |

| Esophageal variceal hemorrhage | 11 (8) | 17 (13) | 0.247 |

| Ascites | 96 (72) | 83 (62) | 0.063 |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | 22 (17) | 9 (7) | 0.011 |

| Portosystemic encephalopathy | 62 (47) | 68 (50) | 0.539 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 6 (5) | 23 (17) | 0.001 |

| End-stage renal disease requiring CRRT/HD | 15 (11) | 13 (10) | 0.644 |

| Treatment of portal hypertension/complications | |||

| Esophageal variceal banding | 11 (8) | 22 (16) | 0.046 |

| TIPS | 3 (2) | 8 (6) | 0.13 |

| Beta-blocker usea | 18 (14) | 38 (28) | 0.004 |

| Diuretic usea | 57 (43) | 65 (48) | 0.415 |

| Large volume paracentesis | 29 (22) | 39 (29) | 0.183 |

| Antibiotics for SBP prophylaxisa | 9 (7) | 11 (8) | 0.68 |

| Lactulose and/or rifaximin usea | 50 (38) | 55 (41) | 0.632 |

| Transplant evaluation | 14 (11) | 19 (14) | 0.402 |

| Liver transplantation | 3 (2) | 10 (7) | 0.05 |

Morphologic appearance of the pancreas was generally similar among patients with CD and ACP Only (Table 3). In regards to the clinical manifestations, patients with ACP Only were more likely to have a history of acute or recurrent acute pancreatitis, receive pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy, ERCP, and pancreatic surgery than patients with CD. Patients with ACP Only were also more likely to have endocrine dysfunction, as characterized by a higher prevalence of diabetes, need for insulin therapy, and poor glycemic control as reflected by a higher hemoglobin A1c level at the time of last contact. Other clinical features or therapies were similar between the two groups.

| Characteristics present | CD (n = 133) | Only ACP (n = 87) | P value |

| Verification criteria fulfilled on imaging | |||

| Pancreatic calcifications | 88 (66) | 64 (74) | 0.246 |

| Moderate-severe ductal dilatation | 38 (29) | 30 (35) | 0.354 |

| Moderate-severe ductal structure | 18 (14) | 14 (16) | 0.599 |

| Any gland atrophy | 77 (58) | 46 (53) | 0.463 |

| Moderate-severe gland atrophy | 10 (13) | 7 (15) | 0.88 |

| Gland atrophy not reported | 67 (87) | 37 (80) | 0.25 |

| Diagnosis based on EUS alone | 6 (5) | 5 (6) | 0.681 |

| Chronic pancreatitis features | |||

| Acute pancreatitis | 101 (76) | 74 (85) | 0.009 |

| Age at first pancreatitis, yr – mean ± SD | 48.1 ± 15.2 | 41.5 ± 10.6 | 0.112 |

| Recurrent acute pancreatitis | 61 (46) | 53 (61) | 0.023 |

| Chronic abdominal paina | 56 (42) | 44 (51) | 0.189 |

| Pancreatic pseudocyst | 29 (22) | 22 (25) | 0.549 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 54 (41) | 50 (58) | 0.011 |

| Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (Fecal elastase < 100 and/or steatorrhea) | 24 (18) | 14 (16) | 0.708 |

| Pancreatic adenocarcinoma | 2 (2) | 4 (5) | 0.163 |

| Treatment of chronic pancreatitis/complications | |||

| Oral anti-diabetic therapya | 11 (20) | 13 (26) | 0.113 |

| Insulin therapya | 46 (85) | 37 (74) | 0.209 |

| Pancreatic enzymatic replacement therapya | 35 (26) | 39 (45) | 0.004 |

| Chronic opiate therapya | 59 (44) | 33 (38) | 0.381 |

| Treatment by chronic pain specialist | 20 (15) | 20 (23) | 0.124 |

| Celiac plexus block | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 0.077 |

| ERCP | 41 (31) | 43 (49) | 0.004 |

| Pseudocyst drainage (endoscopic/surgical) | 18 (14) | 13 (15) | 0.743 |

| Pancreatic surgery | 13 (10) | 19 (22) | 0.012 |

| Pertinent test results | |||

| Hemoglobin A1Ca – mean ± SD | 6.4 ± 2.3 | 7.3 ± 2.1 | 0.01 |

| Vitamin D deficiency | 48 (36) | 25 (29) | 0.104 |

| DEXA scan performed | 28 (21) | 19 (22) | 0.855 |

| Osteopenia on DEXA scan | 12 (43) | 10 (53) | 0.51 |

| Osteopenia on DEXA scan | 8 (29) | 5 (26) | 0.865 |

As the largest study of its kind, this work endeavors to further characterize patients at the intersection of ALC and ACP. Our retrospective analysis of patients with a verified diagnosis of ALC Only, ACP Only or CD reveals that during a similar period of observation, although patients with CD had differences in some disease-related manifestations, they did not have worse phenotype than counterparts with single organ disease. Furthermore, our findings suggest that patients with CD potentially need not be monitored at a higher degree, but the primary focus should be on the management of ALC.

Patients included in this study represent the most severe phenotypes of alcohol-related liver or pancreas disease who received care at a tertiary care center during the course of their illness. Among them, we observed that the dominant phenotype in patients with CD to be similar to that of ALC, specifically the two most important indicators of outcomes (i.e. overall survival and MELD-Na and Child C scores in patients with CD were similar to patients with ALC Only). This suggests that patients with alcohol-related pancreatic disease who are identified to have alcohol-related liver disease need to be assessed and monitored for early identification of cirrhosis or cirrhosis-related complications so they can be managed in a timely manner.

Patients with CD shared similar demographic attributes with those of single organ disease such as the sex distribution of ALC Only patients as well as age, racial distribution and body mass index (BMI) of ACP Only patients. Of note, although our prior study showed that the prevalence of alcohol-related pancreatic disease in those with alcohol-related liver disease was 2-4 folds higher in blacks compared to other races[28], the racial difference was not present in this study. This may be related to the inclusion of patients with the most severe phenotypes in this study as noted above, which may not be representative of the full spectrum of alcohol-related liver and pancreas disease.

When comparing patients with CD with those who had single organ disease, we observed some demographic differences. For instance, patients with CD were younger than those with ALC Only but similar to patients with ACP Only. Although our retrospective study was not designed to evaluate this systematically, a potential explanation is an earlier identification of CP based on clinical symptoms and/or imaging studies in patients with alcohol-related liver disease. Similarly, patients with CD had BMI similar to ACP but lower than patients with ALC likely related to malabsorption. The alternative explanation in a subset of patients with ALC may be fluid retention related to portal hypertension.

Other than spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, patients with CD in general had a lower burden of disease-related manifestations when compared with patients who had ALC Only and ACP Only. The reason for this is unclear but a possible explanation may be the recognition of disease overlap at an earlier stage, e.g. alcohol-related liver disease in patients with ACP or alcohol-related pancreatitis in patients with ALC. In terms of healthcare utilization, the burden of non-elective admissions in patients with CD mirrored those of ACP Only patients.

Strengths of our study include the largest sample size to evaluate the phenotype of patients with CD, rigorous review of medical records to verify diagnosis and data collection by review of medical records and a long observation period which ensures capture of clinical events. Our study also has limitations. Being a retrospective study from a single-center tertiary academic medical center may have resulted in our study population to be of higher complexity and limit generalizability of our findings. Our study population includes patients with concomitant Hepatitis B and C infections. While the prevalence of these infections rates represent the traits of our underlying clinical population, hepatitis B and C infections may attribute to or confound the severity of hepatic disease. Although our review of records within the UPMC system was complimented by availability of medical records from other institutions whenever possible through Care Everywhere, there is a possibility of underestimation of clinical events. Finally, clinical events and demographics have the potential to be misclassified in the dataset due to missing or incomplete information.

Contrary to our working hypothesis, patients with Coexistent ALC and ACP did not have a worse phenotype when compared with single organ disease patients. The dominant phenotype in patients with CD in terms of overall survival and markers of advanced liver disease was similar to patients with ALC Only. CD patients also had lower prevalence of disease-related manifestations when compared with those who had single organ disease. Our findings suggest that patients with CD may not need to be monitored at a higher degree, but the primary focus for longitudinal follow-up should be on ALC.

Heavy alcohol use is a known cause of liver and pancreatic injury that can lead to alcohol-related liver cirrhosis (ALC) and alcohol-related chronic pancreatitis (ACP). These diseases are associated with significant morbidity, mortality, and healthcare utilization and spending.

While both ALC and ACP are well-characterized, there is a subset of patient with both ALC and ACP (coexistent disease) that is poorly understood.

We aim to characterize the clinical profile of patients with coexistent disease (CD) and its differences from those with ALC Only or ACP Only.

The study population consisted of adult patient encounters at UPMC facilities from 2006 to 2017 with more than 12 mo of contact. We identified subsets of patients with ACP Only, ALC Only, and CD based on international classifications of diseases codes and reviewed the Electronic Health Record to verify diagnoses and abstract clinical information. Statistical comparisons were made using t-test and Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Survival from time of first diagnosis is reported using the Kaplan-Meier method. Cox proportional-hazards models are used to report the hazard ratio and 95% confidence intervals while adjusting for age at diagnosis, sex, and race.

The median duration of contact was greater than 10 years and was comparable between groups. The median number of non-elective hospital admissions for CD and ACP Only were comparable and significantly greater than patients with ALC Only. The number of patients who died in follow-up in CD, ALC Only, and ACP Only groups was 80 (60%), 82 (61%), and 36 (41%). Using Cox regression, survival was similar between ALC Only vs ACP Only and CD vs ACP Only. Despite comparable MELD-Na and Child-Pugh scores between CD and ALC Only patients, those with ALC Only were more likely to have esophageal varices, need for variceal banding, treatment with beta blockers, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Patients with ACP Only were more likely to have acute pancreatitis, need for endoscopic or surgical intervention, and endocrine dysfunction.

Patients with CD did not have a worse phenotype compared to patients with ACP Only or ALC Only.

As the largest study of its kind, this work hopes to characterize patients at the intersection of ALC and ACP. Given our findings, we observed that the dominant phenotype in CD is similar to that of ALC Only, suggesting that patients with alcohol-related pancreatic disease who are newly identified to have alcohol-related liver disease should be closely monitored for liver cirrhosis and its complications.

The authors thank the Enhancing MEntoring to Improve Research in GastroEnterology (EMERGE) Program of the Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, University of Pittsburgh for supporting this project.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Maslennikov R, Russia; Tantau AI, Romania S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Table 5.4A—Alcohol Use Disorder in Past Year Among Persons Aged 12 or Older, by Age Group and Demographic Characteristics: Numbers in Thousands, 2018 and 2019. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) 2019. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Rehm J, Taylor B, Mohapatra S, Irving H, Baliunas D, Patra J, Roerecke M. Alcohol as a risk factor for liver cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29:437-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 514] [Cited by in RCA: 439] [Article Influence: 29.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Samokhvalov AV, Rehm J, Roerecke M. Alcohol Consumption as a Risk Factor for Acute and Chronic Pancreatitis: A Systematic Review and a Series of Meta-analyses. EBioMedicine. 2015;2:1996-2002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yadav D, Timmons L, Benson JT, Dierkhising RA, Chari ST. Incidence, prevalence, and survival of chronic pancreatitis: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:2192-2199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nøjgaard C, Bendtsen F, Becker U, Andersen JR, Holst C, Matzen P. Danish patients with chronic pancreatitis have a four-fold higher mortality rate than the Danish population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:384-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Julien J, Ayer T, Bethea ED, Tapper EB, Chhatwal J. Projected prevalence and mortality associated with alcohol-related liver disease in the USA, 2019-40: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e316-e323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 25.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Seitz HK, Bataller R, Cortez-Pinto H, Gao B, Gual A, Lackner C, Mathurin P, Mueller S, Szabo G, Tsukamoto H. Alcoholic liver disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 655] [Cited by in RCA: 814] [Article Influence: 116.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dam MK, Flensborg-Madsen T, Eliasen M, Becker U, Tolstrup JS. Smoking and risk of liver cirrhosis: a population-based cohort study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:585-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wilcox CM, Sandhu BS, Singh V, Gelrud A, Abberbock JN, Sherman S, Cote GA, Al-Kaade S, Anderson MA, Gardner TB, Lewis MD, Forsmark CE, Guda NM, Romagnuolo J, Baillie J, Amann ST, Muniraj T, Tang G, Conwell DL, Banks PA, Brand RE, Slivka A, Whitcomb D, Yadav D. Racial Differences in the Clinical Profile, Causes, and Outcome of Chronic Pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1488-1496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Whitcomb DC, LaRusch J, Krasinskas AM, Klei L, Smith JP, Brand RE, Neoptolemos JP, Lerch MM, Tector M, Sandhu BS, Guda NM, Orlichenko L; Alzheimer's Disease Genetics Consortium, Alkaade S, Amann ST, Anderson MA, Baillie J, Banks PA, Conwell D, Coté GA, Cotton PB, DiSario J, Farrer LA, Forsmark CE, Johnstone M, Gardner TB, Gelrud A, Greenhalf W, Haines JL, Hartman DJ, Hawes RA, Lawrence C, Lewis M, Mayerle J, Mayeux R, Melhem NM, Money ME, Muniraj T, Papachristou GI, Pericak-Vance MA, Romagnuolo J, Schellenberg GD, Sherman S, Simon P, Singh VP, Slivka A, Stolz D, Sutton R, Weiss FU, Wilcox CM, Zarnescu NO, Wisniewski SR, O'Connell MR, Kienholz ML, Roeder K, Barmada MM, Yadav D, Devlin B. Common genetic variants in the CLDN2 and PRSS1-PRSS2 loci alter risk for alcohol-related and sporadic pancreatitis. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1349-1354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Buch S, Stickel F, Trépo E, Way M, Herrmann A, Nischalke HD, Brosch M, Rosendahl J, Berg T, Ridinger M, Rietschel M, McQuillin A, Frank J, Kiefer F, Schreiber S, Lieb W, Soyka M, Semmo N, Aigner E, Datz C, Schmelz R, Brückner S, Zeissig S, Stephan AM, Wodarz N, Devière J, Clumeck N, Sarrazin C, Lammert F, Gustot T, Deltenre P, Völzke H, Lerch MM, Mayerle J, Eyer F, Schafmayer C, Cichon S, Nöthen MM, Nothnagel M, Ellinghaus D, Huse K, Franke A, Zopf S, Hellerbrand C, Moreno C, Franchimont D, Morgan MY, Hampe J. A genome-wide association study confirms PNPLA3 and identifies TM6SF2 and MBOAT7 as risk loci for alcohol-related cirrhosis. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1443-1448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in RCA: 425] [Article Influence: 42.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mellinger JL, Shedden K, Winder GS, Tapper E, Adams M, Fontana RJ, Volk ML, Blow FC, Lok ASF. The high burden of alcoholic cirrhosis in privately insured persons in the United States. Hepatology. 2018;68:872-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wong T, Dang K, Ladhani S, Singal AK, Wong RJ. Prevalence of Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Among Adults in the United States, 2001-2016. JAMA. 2019;321:1723-1725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Scaglione S, Kliethermes S, Cao G, Shoham D, Durazo R, Luke A, Volk ML. The Epidemiology of Cirrhosis in the United States: A Population-based Study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49:690-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 416] [Cited by in RCA: 504] [Article Influence: 50.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Asrani SK, Hall L, Hagan M, Sharma S, Yeramaneni S, Trotter J, Talwalkar J, Kanwal F. Trends in Chronic Liver Disease-Related Hospitalizations: A Population-Based Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:98-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Stepanova M, De Avila L, Afendy M, Younossi I, Pham H, Cable R, Younossi ZM. Direct and Indirect Economic Burden of Chronic Liver Disease in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:759-766.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sankaran SJ, Xiao AY, Wu LM, Windsor JA, Forsmark CE, Petrov MS. Frequency of progression from acute to chronic pancreatitis and risk factors: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1490-1500.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Vipperla K, Kanakis A, Slivka A, Althouse AD, Brand RE, Phillips AE, Chennat J, Papachristou GI, Lee KK, Zureikat AH, Whitcomb DC, Yadav D. Natural course of pain in chronic pancreatitis is independent of disease duration. Pancreatology. 2021;21:649-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Conwell DL, Banks PA, Sandhu BS, Sherman S, Al-Kaade S, Gardner TB, Anderson MA, Wilcox CM, Lewis MD, Muniraj T, Forsmark CE, Cote GA, Guda NM, Tian Y, Romagnuolo J, Wisniewski SR, Brand R, Gelrud A, Slivka A, Whitcomb DC, Yadav D. Validation of Demographics, Etiology, and Risk Factors for Chronic Pancreatitis in the USA: A Report of the North American Pancreas Study (NAPS) Group. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:2133-2140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gandhi S, de la Fuente J, Murad MH, Majumder S. Chronic Pancreatitis Is a Risk Factor for Pancreatic Cancer, and Incidence Increases With Duration of Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2022;13:e00463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Machicado JD, Amann ST, Anderson MA, Abberbock J, Sherman S, Conwell DL, Cote GA, Singh VK, Lewis MD, Alkaade S, Sandhu BS, Guda NM, Muniraj T, Tang G, Baillie J, Brand RE, Gardner TB, Gelrud A, Forsmark CE, Banks PA, Slivka A, Wilcox CM, Whitcomb DC, Yadav D. Quality of Life in Chronic Pancreatitis is Determined by Constant Pain, Disability/Unemployment, Current Smoking, and Associated Co-Morbidities. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:633-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Aparisi L, Sabater L, Del-Olmo J, Sastre J, Serra MA, Campello R, Bautista D, Wassel A, Rodrigo JM. Does an association exist between chronic pancreatitis and liver cirrhosis in alcoholic subjects? World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6171-6179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Nakamura Y, Kobayashi Y, Ishikawa A, Maruyama K, Higuchi S. Severe chronic pancreatitis and severe liver cirrhosis have different frequencies and are independent risk factors in male Japanese alcoholics. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:879-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Aoufi Rabih S, García Agudo R, Legaz Huidobro ML, Ynfante Ferrús M, González Carro P, Pérez Roldán F, Ruiz Carrillo F, Tenías Burillo JM. Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and chronic pancreatitis in chronic alcoholic liver disease: coincidence or shared toxicity? Pancreas. 2014;43:730-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Rasineni K, Srinivasan MP, Balamurugan AN, Kaphalia BS, Wang S, Ding WX, Pandol SJ, Lugea A, Simon L, Molina PE, Gao P, Casey CA, Osna NA, Kharbanda KK. Recent Advances in Understanding the Complexity of Alcohol-Induced Pancreatic Dysfunction and Pancreatitis Development. Biomolecules. 2020;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Li H, Yang Z, Tian F. Clinical Characteristics and Risk Factors for Sinistral Portal Hypertension Associated with Moderate and Severe Acute Pancreatitis: A Seven-Year Single-Center Retrospective Study. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:5969-5976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Singhvi A, Abromitis R, Althouse AD, Bataller R, Arteel GE, Yadav D. Coexistence of alcohol-related pancreatitis and alcohol-related liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pancreatology. 2020;20:1069-1077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Arteel GE, Singhvi A, Feldman R, Althouse AD, Bataller R, Saul M, Yadav D. Coexistent Alcohol-Related Liver Disease and Alcohol-Related Pancreatitis: Analysis of a Large Health Care System Cohort. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67:2543-2551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |