Published online Jul 27, 2021. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v13.i7.774

Peer-review started: February 7, 2021

First decision: May 13, 2021

Revised: May 28, 2021

Accepted: July 2, 2021

Article in press: July 2, 2021

Published online: July 27, 2021

Processing time: 165 Days and 13.5 Hours

The displacement of spleen from its normal location to other places is known as wandering spleen (WS) and is a rare disease. The repeated torsion of WS is due to the presence of long pedicle and absence/laxity of anchoring ligaments. A WS is an extremely rare cause of left-sided portal hypertension (PHT) and severe gastric variceal bleeding. Left-sided PHT usually occurs as a result of splenic vein occlusion caused by splenic torsion, extrinsic compression of the splenic pedicle by enlarged spleen, and splenic vein thrombosis. There is a paucity of data on WS-related PHT, and these data are mostly in the form of case reports. In this review, we have analyzed the data of 20 reported cases of WS-related PHT. The mechanisms of pathogenesis, clinico-demographic profile, and clinical implications are described in this article. The majority of patients were diagnosed in the second to third decade of life (mean age: 26 years), with a strong female preponderance (M:F = 1:9). Eleven of the 20 WS patients with left-sided PHT presented with abdominal pain and mass. In 6 of the 11 patients, varices were detected incidentally on preoperative imaging studies or discovered intraoperatively. Therefore, pre-operative search for varices is required in patients with splenic torsion.

Core Tip: Wandering spleen (WS) is a rare disease. The repeated torsion of WS is due to the presence of long pedicle and absence/laxity of anchoring ligaments.WS is an extremely rare cause of left-sided portal hypertension and severe gastric variceal bleeding. This review comprehensively describes the pathophysiological mechanisms, clinico-demographic profile, and clinical implications of torsion of the spleen. In patients with splenic torsion, varices can be detected incidentally on preoperative imaging studies or intraoperatively. Therefore, pre-operative search for varices is required in patients with splenic torsion.

- Citation: Jha AK, Bhagwat S, Dayal VM, Suchismita A. Torsion of spleen and portal hypertension: Pathophysiology and clinical implications. World J Hepatol 2021; 13(7): 774-780

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v13/i7/774.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v13.i7.774

The displacement of spleen from its normal location to other places is known as wandering spleen (WS). It is a rare clinical entity in which the spleen is attached by a long vascular pedicle. It was first described by Van Horne in 1667[1]. WS-also known as splenoptosis or ectopic spleen or floating spleen or aberrant spleen-most commonly located in the pelvic cavity.

The spleen is anchored to its normal position by splenorenal and gastrosplenic ligaments. Due to absence or laxity of these ligaments, the spleen is displaced from the left hypochondrium to other places in the abdominal cavity. The laxity or absence of splenorenal and gastrosplenic ligaments can be caused by congenital or acquired pathology. Congenital causes of WS include an incomplete fusion of the dorsal mesogastrium and the parietal peritoneum, resulting in the absence of anchoring ligament formation[2,3]. While acquiring causes include pregnancy due to hormonal effects, lax abdominal wall in multiparous women or obese persons and splenomegaly. More than one risk factor can be involved in the pathogenesis of WS

The true incidence of WS is unknown. The incidence of WS was 0.2% in splenectomies performed in 1003 patients. The patient is usually asymptomatic and remains undiagnosed for long periods. A WS is usually diagnosed in childhood and the third and fourth decades of life, with a strong female preponderance. In a study, Viana et al[4] reviewed the data of 266 cases of WS and found that the average age at the time of diagnosis was 25.2 years, with a male-female ratio of 3.3:1.

More than half of the patients present with recurrent abdominal pain due to repeated torsion. Abdominal mass is the most common finding on examination[5-8]. In a systematic review, 197 (M:F = 1.5:1) pediatric patients with WS were analyzed, and abdominal pain was found to be the most frequent (43%) symptom[7]. Another systematic review was performed in 376 surgically treated patients of WS. Abdominal pain and abdominal mass were the most frequent clinical features. More importantly, nearly half of the patients presented with acute clinical onset[8]. The diagnosis of a complicated WS needs a high index of suspicion. Delay in diagnosis can lead to emergency surgeries. It can be avoided by reducing time-consuming repeated imaging studies[9].

WS can be complicated with splenic torsion, splenic infarction, hypersplenism and left-sided portal hypertension (PHT). Acute abdomen, splenic abscess, acute pancreatitis, pancreatic necrosis, gastric volvulus, pancreatic volvulus, intestinal obstruction, and gastric outlet obstruction are the other rare complications of WS[5,10-15].

Splenic torsion is the most common complication of WS. In a systematic review, splenic torsion was diagnosed in 56% of pediatric patients with WS[7]. The repeated torsion of WS is due to the presence of long pedicle and absence/Laxity of anchoring ligaments. Torsion usually occurs clockwise. Torsion of pedicle leads to increased back pressure in splenic vein (SV), resulting in parenchymal congestion, splenomegaly, and hypersplenism. Extreme torsion can lead to the arterial supply being compromised, causing infarction and necrosis. The enlargement of the spleen further aggravates splenic torsion. Torsion can be precipitated by movements of the body, changes in intra-abdominal pressure, peristalsis, or distension of adjacent organs[16,17].

WS is diagnosed using abdominal ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging. US demonstrates the absence of spleen from its normal position and its location elsewhere in the abdominal cavity. US examination is limited by the presence of gas, suboptimal assessment of adjacent viscera and difficulty in identifying twisted pedicle and the infarcted spleen. CT scan is the preferred modality of investigation for the diagnosis of WS. CT scans delineate the exact location of the spleen and demonstrates the twisting of the splenic pedicle known as whirl sign-alternating radiolucent and radio dense bands formed due to splenic vessels and adjacent fat. The whorled appearance of splenic vessels and surrounding fat is diagnostic of splenic torsion. CT scans also demonstrate other associated findings, such as ascites and entrapment of the adjoining viscera secondary to torsion. Scintigraphy and angiography can also diagnose WS but are rarely used due to their high costs and invasive nature[18-21].

Splenopexy is the first-line treatment of WS and is indicated even in asymptomatic patients (except elderly and high-risk surgical candidates) because of the potential risk of serious complications. Detorsion and splenopexy are preferred in patients with torsion, whose spleen parenchyma is shown to be viable and without signs of hypersplenism. Splenectomy is considered in cases of splenic infarction, splenic vessel thrombosis (SVT), portal vein thrombosis (PVT), hypersplenism, PHT, and suspicion of cancer[5,22]. In recent years, there has been a growing trend toward more conservative and minimally invasive approaches, such as splenopexy or laparoscopic techniques[4,7,8,23,24]. Viana et al[4] reviewed the data of 266 cases of WS and found that splenectomy and splenopexy were performed in 70% and 29% of patients, respectively. The majority of patients had open surgery (79%), while about one-fifth of patients were treated using laparoscopic surgery. A very recent systematic review by Ganarin et al[7] showed that splenectomy and splenopexy were performed in 55% and 39% of surgically treated patients (n = 197), respectively. About half of the splenopexies were performed using minimally invasive surgery. Frequently used techniques were the placement of a mesh (46%) or the construction of a retroperitoneal pouch (31%). Overall, splenopexy was effective in 95% of cases.

Left-sided PHT, also known as segmental or sinistral PHT, is a rare cause of gastric variceal bleeding. It usually occurs as a result of SV occlusion caused by splenic torsion, extrinsic compression of splenic pedicle and SVT. Left-sided PHT should be suspected in those who have gastric and/or splenic varices in the absence of esophageal varices and deranged liver function test. WS is an extremely rare cause of left-sided PHT[16].

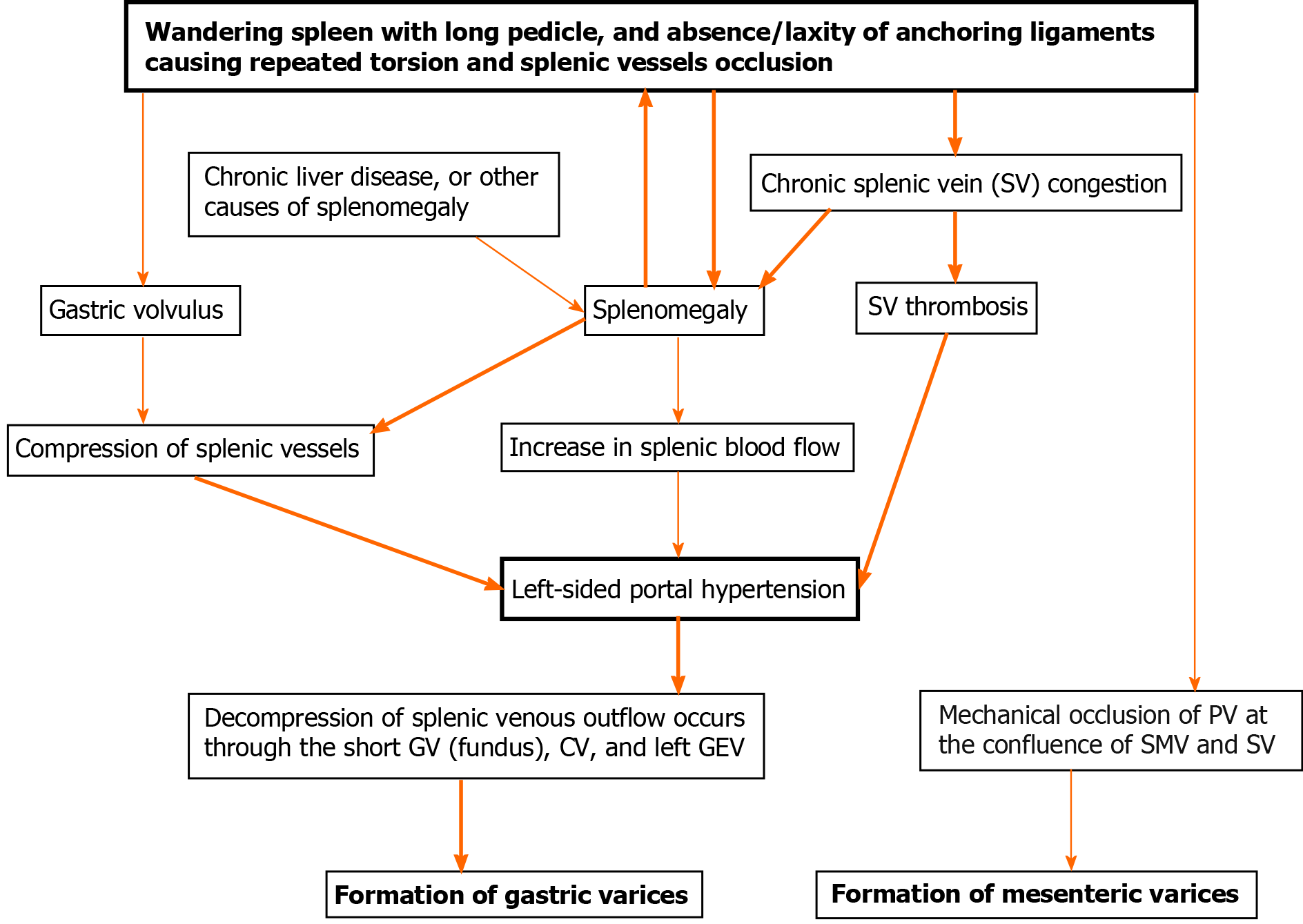

The torsion of WS occurs mainly due to absence/laxity of anchoring ligaments, long pedicle and splenomegaly. Splenic torsion can also be predisposed by other causes of splenomegaly, including chronic liver disease (CLD), malaria, myeloproliferative disease, lymphoproliferative disorders, infectious mononucleosis, and splenic haemorrhagic cyst[5]. The torsion of the splenic pedicle leads to increased back pressure in the SV, resulting in splenic parenchymal congestion and splenomegaly. The occlusion of the SV can be caused by the chronic torsion of the splenic pedicle, SVT, and direct mechanical compression by an enlarged spleen. SV occlusion leads to impaired venous return and retrograde filling of the short gastric and left gastroepiploic veins. Decompression of splenic venous outflow occurs through the short gastric veins, coronary vein, and left gastroepiploic veins, producing gastric varices[16]. A few cases of mesenteric varices have been described in WS patients without PVT. The mechanical occlusion of the portal vein at the level of superior mesenteric and SV confluence due to splenic torsion can explain the mechanism of formation of mesenteric varices[25-28]. The coexisting gastric volvulus can further obstruct the venous drainage of the proximal stomach, leading to the development of PHT[12]. The pathophysiologic mechanisms of PHT in WS patients are shown in Figure 1.

Left-sided PHT is a rare manifestation of WS with torsion. Approximately 20 cases of WS with left-sided PHT have been described in English medical literature[5,11-13,25-39]. The clinico-demographic profile of the reported cases of patients with WS and PHT are summarized in Table 1. The majority of patients were diagnosed in the second or third decade of life (mean age: 26 years), with a strong female preponderance (M:F = 1:9). WS patients with PHT present earlier than WS patients without PHT. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding was the most common presenting complaint, followed by abdominal pain. The majority of the patients had gastric varices without esophageal varices, which is suggestive of left-sided PHT. Mesenteric varices and splenic varices were identified in about 25% of patients. In 14 patients, gastric varices were diagnosed in endoscopy or gastrointestinal series. In five patients, the presence of varices was only identified in imaging studies. One patient had intra-operative diagnosis of PHT. Splenectomy was performed on all patients, and the follow-up details of 14 patients revealed the disappearance of varices.

| Clinico-demographic features | Remarks | Frequency (%) |

| Reported cases (n) | 20 | |

| Mean age (range) | 26.15 (12-55) yr | |

| Male:female ratio | 1:9 | |

| Presenting complaints | Upper GI bleeding | 9 (45) |

| Abdominal pain | 8 (40) | |

| Abdominal mass | 2 (10) | |

| Acute pancreatitis | 1 (5) | |

| Type of varices | Gastric varices | 18 (90) |

| Mesentric varices | 5 (25) | |

| Splenic varices | 6 (30) | |

| Diagnosis of varices | Endoscopy | 12 (60) |

| GI series | 2 (10) | |

| Imaging only | 5 (25) | |

| Intra-operative | 1 (5%) | |

| Venous thrombosis | Splenic vein | 3 (15) |

| Portal vein | 1 (5) | |

| Splenic infarction | 4 (20) | |

| Definitive treatment | Splenectomy | 20 (100) |

| Post-operative variceal status | Documented (n) | 14/20 (70) |

| Resolved (n) | 14/14 (100) |

Esophageal varices are absent in WS patients with left-sided PHT. Coexisting CLD has been described in two-patients with WS[40,41]. Splenomegaly resulting from CLD can further aggravate the splenic torsion and PHT[40]. PVT has also been described in patients with WS[28,42,43]. Hence, the presence of esophageal varices in patients with WS warrants careful evaluation for coexisting CLD and PVT.

Splenectomy eliminates PHT, provides symptomatic relief, and prevents the relapse of varices (Table 1). However, splenectomy in patients with undiagnosed collaterals can be tricky due to increased blood loss. Splenectomy in these patients can necessitate additional transfusions of blood and blood products. Eleven patients of WS with undiagnosed PHT were presented with abdominal pain and mass. In six patients, varices were detected incidentally on preoperative imaging studies or discovered intraoperatively. Therefore, pre-operative search for varices with endoscopy and a good quality CT-scan are useful in patients with splenic torsion. These patients also require intra-operative inspection for small collaterals and careful dissection.

The repeated torsion of WS can lead to splenomegaly, SVT, hypersplenism, and, rarely left-sided PHT. The patients with WS and PHT usually present with gastric variceal bleeding. Nearly half of the WS patients with PHT can present without variceal bleeding. Splenectomy or splenopexy in patients with undiagnosed collaterals can be tricky due to increased blood loss. Therefore, pre-operative search for varices is required in patients with splenic torsion. They also require intra-operative inspection for small collaterals and careful dissection. Esophageal varices are absent in WS patients with left-sided PHT. Hence, the presence of esophageal varices in patients with WS warrants careful evaluation for coexisting CLD and PVT.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: India

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chen F, Romano L, Sarti D, Zhang H S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Lane TM, South LM. Management of a wandering spleen. J R Soc Med. 1999;92:84-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Woodward DA. Torsion of the spleen. Am J Surg. 1967;114:953-955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Quinlan RM. Anatomy and physiology of the spleen. In: Shackelford RT, Zuidema GD. Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1983: 631-637. |

| 4. | Viana C, Cristino H, Veiga C, Leão P. Splenic torsion, a challenging diagnosis: Case report and review of literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;44:212-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tan HH, Ooi LL, Tan D, Tan CK. Recurrent abdominal pain in a woman with a wandering spleen. Singapore Med J. 2007;48:e122-e124. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Reisner DC, Burgan CM. Wandering Spleen: An Overview. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2018;47:68-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ganarin A, Fascetti Leon F, La Pergola E, Gamba P. Surgical Approach of Wandering Spleen in Infants and Children: A Systematic Review. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2021;31:468-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Barabino M, Luigiano C, Pellicano R, Giovenzana M, Santambrogio R, Pisani A, Ierardi AM, Palamara MA, Consolo P, Giacobbe G, Fagoonee S, Eusebi LH, Opocher E. "Wandering spleen" as a rare cause of recurrent abdominal pain: a systematic review. Minerva Chir. 2019;74:359-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cohen O, Baazov A, Samuk I, Schwarz M, Kravarusic D, Freud E. Emergencies in the Treatment of Wandering Spleen. Isr Med Assoc J. 2018;20:354-357. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Seif Amir Hosseini A, Streit U, Uhlig J, Biggemann L, Kahl F, Ahmed S, Markus D. Splenic torsion with involvement of pancreas and descending colon in a 9-year-old boy. BJR Case Rep. 2019;5:20180051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gilman RS, Thomas RL. Wandering spleen presenting as acute pancreatitis in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:1100-1102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Daneshgar S, Eras P, Feldman SM, Cacace VA, Federico FN, Levin RH. Bleeding gastric varices and gastric torsion secondary to a wandering spleen. Gastroenterology. 1980;79:141-143. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Gupta J, Sharma N, Devkaran B, Gupta A. Acute gastric volvulus with torsion wandering spleen: A rare surgical emergency. Saudi Surg J. 2013;1:53-56. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ooka M, Kohda E, Iizuka Y, Nagamoto M, Ishii T, Saida Y, Shimizu N, Gomi T. Wandering spleen with gastric volvulus and intestinal non-rotation in an adult male patient. Acta Radiol Short Rep. 2013;2:2047981613499755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gorsi U, Bhatia A, Gupta R, Bharathi S, Khandelwal N. Pancreatic volvulus with wandering spleen and gastric volvulus: an unusual triad for acute abdomen in a surgical emergency. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:195-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Thompson RJ, Taylor MA, McKie LD, Diamond T. Sinistral portal hypertension. Ulster Med J. 2006;75:175-177. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Desai DC, Hebra A, Davidoff AM, Schnaufer L. Wandering spleen: a challenging diagnosis. South Med J. 1997;90:439-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gordon DH, Burrell MI, Levin DC, Mueller CF, Becker JA. Wandering spleen--the radiological and clinical spectrum. Radiology. 1977;125:39-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Parada Blázquez MJ, Rodríguez Vargas D, García Ferrer M, Tinoco González J, Vargas Serrano B. Torsion of wandering spleen: radiological findings. Emerg Radiol. 2020;27:555-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gayer G, Zissin R, Apter S, Atar E, Portnoy O, Itzchak Y. CT findings in congenital anomalies of the spleen. Br J Radiol. 2001;74:767-772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Maksoud SF, Swamy N, Khater NH. Tale of a wandering spleen: 1800 degree torsion with infarcted spleen and secondary involvement of liver. J Radiol Case Rep. 2014;8:18-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Soleimani M, Mehrabi A, Kashfi A, Fonouni H, Büchler MW, Kraus TW. Surgical treatment of patients with wandering spleen: report of six cases with a review of the literature. Surg Today. 2007;37:261-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Alqadi GO, Saxena AK. Is laparoscopic approach for wandering spleen in children an option? J Minim Access Surg. 2018;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Safaya A, Piscina A, Con J. Wandering Spleen With Splenic Torsion and Pancreatitis : Spleen Preserving Management. Am Surg. 2020;3134820945288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wani S, Abdulkarim AB, Buckles D. Gastric variceal hemorrhage secondary to torsion of wandering spleen. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:A24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Rafie BA, AbuHamdan OJ, Trengganu NS, Althebyani BH, Almatrafi BS. Torsion of a wandering spleen as a cause of portal hypertension and mesenteric varices: a rare aetiology. J Surg Case Rep. 2018;2018:rjy107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Singla V, Galwa RP, Khandelwal N, Poornachandra KS, Dutta U, Kochhar R. Wandering spleen presenting as bleeding gastric varices. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:637.e1-637.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zarroug AE, Hashim Y, El-Youssef M, Zeidan MM, Moir CR. Wandering spleen as a cause of mesenteric and portal varices: a new etiology? J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:e1-e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Smulewicz JJ, Clemett AR. Torsion of the wandering spleen. Am J Dig Dis. 1975;20:274-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Köseoğlu H, Atalay R, Büyükaşık NŞ, Canyiğit M, Özer M, Solakoğlu T, Akın FE, Bolat AD, Yürekli ÖT, Ersoy O. An Unusual Reason for Gastric Variceal Hemorrhage: Wandering Spleen. Indian J Surg. 2015;77:750-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Aaqib M, Omair S, Naseer C, Tahleel S, Ovais B, Faiz S, Mubashir S. Wandering spleen with torsion of splenic vein and gastric varicies. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep. 2021;65:101756. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Sharma R, Shah A, Benedict M. Recurrent Abdominal Pain and Gastrointestinal Bleeding due to Splenic Torsion in a Young Male. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105 (Suppl1):S 282. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 33. | Uy PPD, Naik S. Torsion of a wandering spleen with splenic and gastric varices presenting as abdominal pain. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112 (Suppl1):S1436. |

| 34. | Sorgen RA, Robbins DI. Bleeding gastric varices secondary to wandering spleen. Gastrointest Radiol. 1980;5:25-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Irak K, Esen I, Keskın M, Emınler AT, Ayyildiz T, Kaya E, Kiyici M, Gürel S, Nak SG, Gülten M, Dolar E. A case of torsion of the wandering spleen presenting as hypersplenism and gastric fundal varices. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2011;22:93-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Angerås U, Almskog B, Lukes P, Lundstam S, Weiss L. Acute gastric hemorrhage secondary to wandering spleen. Dig Dis Sci. 1984;29:1159-1163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Melikoğlu M, Colak T, Kavasoğlu T. Two unusual cases of wandering spleen requiring splenectomy. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1995;5:48-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Chue KM, Tan JKH, Pang NQ, Kow AWC. Laparoscopic splenectomy for a wandering spleen with resultant splenomegaly and gastric varices. ANZ J Surg. 2020;90:2124-2125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Sato M, Miyaki Y, Tochikubo J, Onoda T, Shiiya N, Wada H. Laparoscopic splenectomy for a wandering spleen complicating gastric varices: report of a case. Surg Case Rep. 2015;1:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Jha AK, Ranjan R, Priyadarshi RN. Wandering Spleen and Portal Hypertension: A Vicious Interplay. ACG Case Rep J. 2017;4:e54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Satpathi T, Mukhopadhyay S. Ectopic spleen with cirrhosis of liver. J Assoc Physicians India. 2008;56:819-820. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Yilmaz C, Esen OS, Colak A, Yildirim M, Utebay B, Erkan N. Torsion of a wandering spleen associated with portal vein thrombosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24:379-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Makhlouf NA, Morsy KH, Ammar S, Mohammed RA, Yousef HA, Mostafa MG. Wandering spleen in the pelvic region in an adult man with symptoms of acute abdomen. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2016;17:49-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |