Published online Aug 27, 2019. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v11.i8.656

Peer-review started: April 29, 2019

First decision: June 3, 2019

Revised: June 14, 2019

Accepted: August 20, 2019

Article in press: August 20, 2019

Published online: August 27, 2019

Processing time: 117 Days and 10.5 Hours

Fascioliasis is caused by watercress and similar freshwater plants or drinking water or beverages contaminated with metacercariae. Fascioliasis can radiologically mimic many primary or metastatic liver tumors. Herein, we aimed to present the treatment process of a patient with fascioliasis mimicking colon cancer liver metastasis.

A 35-year-old woman who underwent right hemicolectomy due to cecum cancer was referred to our clinic for management of colon cancer liver metastasis. Both computed tomography and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography revealed several tumoral lesions localized in the right lobe of the liver. After a 6-course FOLFOX (folinic acid, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin) and bevacizumab regimen, the hypermetabolic state on both liver and abdominal lymph nodes continued, and chemotherapy was extended to a 12-course regimen. The patient was referred to our institute when the liver lesions were detected to be larger on dynamic liver magnetic resonance imaging 6 weeks after completion of chemotherapy. Right hepatectomy was performed, and histopathological examination was compatible with fascioliasis. Fasciola hepatica IgG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was positive. The patient was administered two doses of triclabendazole (10 mg/kg/dose) 24 h apart. During the follow-up period, dilatation was detected in the common bile duct, and Fasciola parasites were extracted from the common bile duct by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Triclabendazole was administered to the patient after ERCP.

Parasitic diseases, such as those caused by Fasciola hepatica, should be kept in mind in the differential diagnosis of primary or metastatic liver tumors, such as colorectal cancer liver metastasis, in patients living in endemic areas.

Core tip: Human fascioliasis is caused by drinking water or freshwater plants (watercress, etc.) contaminated with metacercariae. Fascioliasis may remain asymptomatic for many years and is usually detected incidentally during radiological examinations for other reasons. Radiologically, fascioliasis can be confused with many other benign and malignant hepatobiliary diseases. One of the most common malignant liver diseases mimicking fascioliasis includes colon cancer liver metastasis. We aimed to present the diagnosis and treatment process in a patient with fascioliasis radiologically mimicking colon cancer liver metastasis.

- Citation: Akbulut S, Ozdemir E, Samdanci E, Unsal S, Harputluoglu M, Yilmaz S. Fascioliasis presenting as colon cancer liver metastasis on 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography: A case report. World J Hepatol 2019; 11(8): 656-662

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v11/i8/656.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v11.i8.656

Fascioliasis (liver fluke) is a parasitic disease of the liver caused by a type of tre-matode of the species Fasciola hepatica and less frequently by F. gigantica. Humans are infected by ingesting metacercariae-containing watercress and similar freshwater plants or drinking contaminated water. After ingestion of contaminated water or beverages, the metacercariae excyst in the duodenum, and the larvae migrate through the intestinal wall into the peritoneum. After penetrating the liver capsule, the larvae pass through the liver parenchyma and reach the biliary ducts, where they develop into adult flukes[1,2]. During this migration, they cause destruction in the liver parenchyma, which is characterized by necrosis and fibrosis. The larval form matures to a 3-cm long and 1-cm wide leaf-shaped adult form in approximately 12 wk. Parasites in the biliary ducts remain asymptomatic for years in most patients and are usually detected incidentally during radiological examinations for other reasons. The most important steps in the diagnosis of fascioliasis are clinical suspicion, detection of eggs in the stool, serological tests, molecular tests, and endoscopic and radiological examinations. Radiologically, fascioliasis can be confused with many other benign and malignant diseases of the liver and biliary tract[3]. We aimed to present the diagnosis and treatment process of a patient with fascioliasis radiologically mimicking liver metastasis of colon cancer.

A 35-year-old female patient who underwent right hemicolectomy for cecal cancer was referred to our Liver Transplant Institute for surgical treatment of colon cancer liver metastasis.

Patient stated that she had been eating watercress for a long time.

The patient stated that she underwent colonoscopy at another clinic because of exhaustion, fatigue, and anemia, and right hemicolectomy was performed upon detection of a cecal tumor on colonoscopy. Histopathological examination revealed cecal adenocarcinoma with subserosal fat tissue invasion and five metastatic lymph nodes in 32 lymph nodes. Preoperative contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed hypodense and heterogenous lesions with soft tissue density that were 40 mm x 33 mm in diameter in the right lobe of the liver (Figure 1). At the 3rd postoperative week, multiple hypermetabolic lesions with SUVmax of 5.3 in segments V, VII, and VIII of the liver were detected on performing 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT (18F-FDG-PET/CT) after 5.5 mCi 18F-FDG injection (Figure 2). In addition, hypermetabolic lesions were detected in the subhepatic (SUVmax: 7.1), superior mesenteric (SUVmax: 7.1), and aortocaval window (SUVmax: 7.3). Six cycles of adjuvant FOLFOX (folinic acid, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin) and bevacizumab were administered to the patient. In control 18F-FDG-PET/CT, the SUVmax values of liver lesions decreased to 3.8, and the SUVmax values of the lymph nodes did not regress. Thus, the same chemotherapy regimen was continued, and control 18F-FDG-PET/CT was performed at the end of 12th che-motherapy course. In the last 18F-FDG-PET/CT, all previously seen lesions were stable, whereas they regressed significantly both dimensionally and metabolically. Subsequently, the patient was referred to our center. Dynamic liver magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed immediately after the 12th chemotherapy course showed regression of the lesions in the liver. After 6 weeks, dynamic MRI at our center revealed that the lesions were more prominent than those on previous magnetic resonance images. Because the patient had colon cancer, the lesions in the liver were hypermetabolic in 18F-FDG-PET/CT, and the lesions started to regrow after chemotherapy, and the patient planned to undergo surgery. Right hepatectomy was performed to include all lesions with intraoperative ultrasonography. In addition, all lymph nodes in the hepatoduodenal ligament, celiac, and aortocaval window were resected, and a frozen section was sent for analysis, and no tumor was detected in the lymph nodes. In the histopathological examination of the hepatectomy specimen, the lesions had granulomatous foci on a tract, characterized by suppuration enriched with eosinophils (Figure 3-4), which was noted to be compatible with F. hepatica infection by a pathologist. Based on this result, preoperative blood tests of the patient were reexamined, and eosinophil count was 0.78 × 109/L (normal range: 0–0.5). F. hepatica IgG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Synlab MVZ Leinfelden GmbH, Leinfelden-Echterdingen, Germany) was positive.

The final diagnosis of the presented case is fascioliasis mimicking colon cancer liver metastasis.

The patient was administered two doses (10 mg/kg/dose) of triclabendazole (Egaten, Novartis Pharma, Switzerland) 24 h apart.

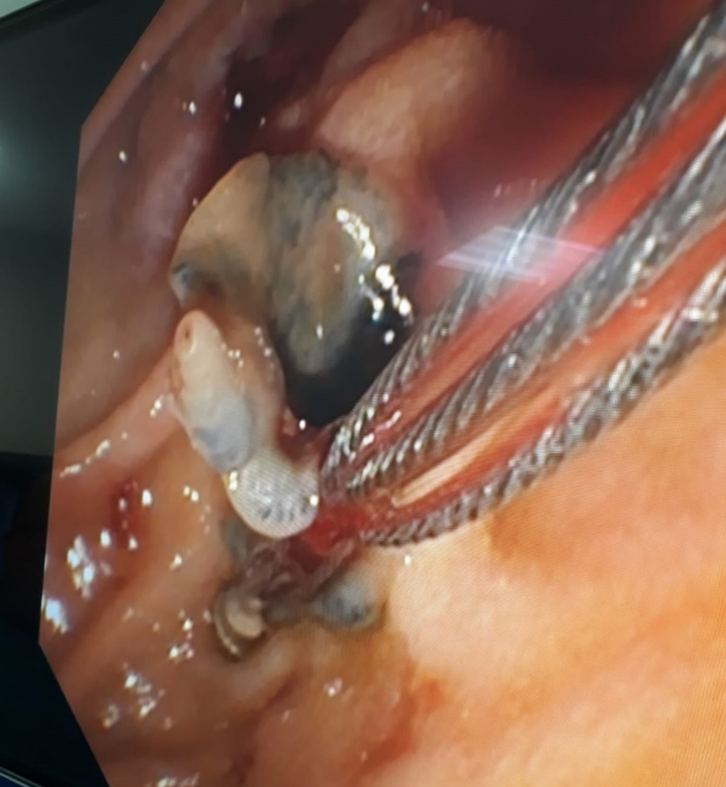

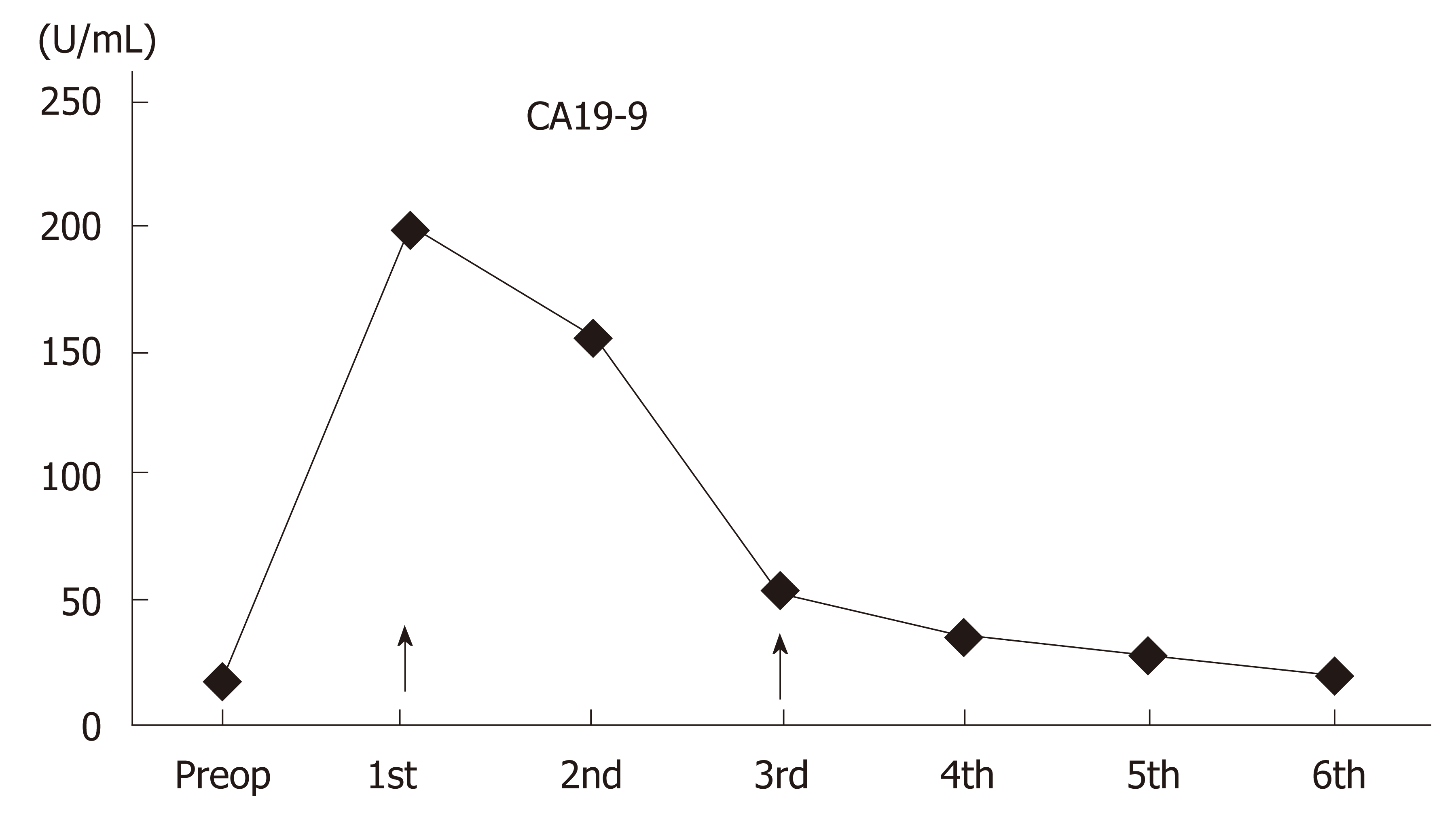

At the 4th postoperative month follow-up, the alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl transferase values were elevated, and the common bile duct was significantly dilated on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) images. Several Fasciola parasites were extracted from the common bile duct with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) (Figure 5). Triclabendazole (10 mg/kg/dose) therapy was administered to the patient after ERCP. The patient is still followed up without hepatobiliary complications. Although blood alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels were normal during the follow-up period, the CA19-9 level showed changes in the postoperative period (Figure 6). However, the CA19-9 level dramatically decreased after ERCP and returned to normal limits (normal range: 0–35 U/mL). No findings of dead or living parasites were detected in the last control ERCP.

Two phases in the life cycle of F. hepatica have been defined: acute (hepatic) and chronic (biliary). The phase where the parasite penetrates through the liver capsule and invades the liver parenchyma is the hepatic phase. In this phase, parasites digest hepatocytes, open tunnels in the parenchyma, and remain in the parenchyma for months[2,4]. Signs and symptoms in the hepatic phase commonly mimic those of liver abscess[2,5]. Patients in this phase usually experience non-specific symptoms, such as loss of appetite, weight loss, right upper quadrant pain, fever, sweating, urticaria, and arthralgia[6]. Hepatomegaly, right upper quadrant pain, and prominent eosinophilia can be seen[4,5]. The phase where the parasite becomes visible in the bile ducts is the biliary phase. In this phase, signs and symptoms, such as biliary colic, epigastric pain, and jaundice, which are related to biliary tract obstruction, develop. The level of cholestatic enzymes and bilirubin may increase[7]. Symptoms of acute pancreatitis may develop in patients with distal bile duct obstruction[8].

The following diagnostic modalities are used in the diagnosis of fascioliasis: clinical suspicion, parasite eggs observed by direct microscopy (stool, bile, or duodenal aspirate), detection of DNA of the parasite with real-time polymerase chain reaction (stool, bile or duodenal aspirate), serological tests (immunoelectrophoresis, counter-immunoelectrophoresis, metacercarial precipitin test, indirect hemagglutination), complement fixation, immunofluorescence assay, radioimmunoassays, enzyme-linked immunofiltration assay (ELIFA), enzyme-linked immuno-electrotransfer blot (EITB) or western blot, Falcon assay screening test–ELISA (FAST-ELISA), micro-ELISA, dot-ELISA], radiological examination of lesions of the liver parenchyma and biliary ducts (CT, MRI, MRCP, and 18F-FDG-PET/CT), endoscopic examination of parasite directly (ERCP, endo-ultrasonography) and histopathological examination of the parasite on tissue biopsy[3,9,10].

Appearance of parasite eggs in the stool has a diagnostic value only in the biliary phase[5,9]. Eosinophilia and anemia may be seen in biochemical tests[3,11]. ELISA is the leading serological test with high sensitivity and rapid results[6]. However, it should be supported by radiological findings due to its high false positive and negative rates[12]. Appearance of tunnel-like linear and branched hypodense lesions on CT is characteristic[3]. In most patients, iso-hyperintense (T2) and iso-hypointense (T1) lesions can be seen on MR and MRCP images, and these lesions can mimic malignant diseases of the biliary tract. ERCP and endoscopic ultrasonography are very useful in the biliary phase[9,11]. Similar to this case, ERCP is the most appropriate treatment modality both to remove parasites from the bile ducts and to decompress the bile ducts.

Diagnosis, staging, response to treatment, and recurrence of malignant diseases can be determined successfully by 18F-FDG-PET/CT. However, false-positive results can be obtained in inflammations due to radiotherapy and surgery or in various chronic infections. These can sometimes mimic malignancy[13-15]. Similar to this case, carefully evaluating high FDG uptake in PET/CT is particularly important in a patient with malignancy. Otherwise, because patients can only be cured with anti-helminthic treatment, they may undergo unnecessary major surgical procedures or che-motherapy.

The most common diseases confused with fascioliasis are viral hepatitis, liver abscess, cholecystitis, sclerosing cholangitis, AIDS-associated cholangitis, ruptured hydatid cyst, and ascariasis, clonorchiasis, and primary and metastatic tumors of the liver and biliary tract[2,5,9]. Therefore, misinterpretation of these signs and symptoms in areas where fascioliasis is not endemic is possible, and thus, diagnosis may be delayed[9]. Similar to this case, in a patient with colon cancer, it is expected that liver lesions will be interpreted as a tumor by a radiologist or nuclear medicine specialist without experience in fascioliasis.

The first and best option for the treatment of fascioliasis is triclabendazole, and another alternative drug is nitazoxanide. Triclabendazole is used in two doses (10 mg/kg/dose) 24 h apart and is effective at all stages regardless of the phase of the disease. Nitazoxanide is a good alternative to triclabendazole, and it is administered as 500 mg twice daily for 7 d[16]. Other drugs that were used previously and are no longer recommended due to drug resistance or toxicity, including bithionol, praziquantel, emetine, dehydroemetine, metronidazole, albendazole, niclofolan, and chloroquine. In this case, we had to administer it twice in a few months.

Fascioliasis may mimic many benign and malignant diseases of the liver due to its non-specific signs and symptoms. Differential diagnosis is quite difficult, if there is no clinical suspicion, especially in patients with simultaneous fascioliasis and gastrointestinal malignancy. Therefore, careful evaluation of diagnostic imaging tools in patients living in endemic areas and the use of other diagnostic tools in suspected cases are vital.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Turkey

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Mas-Coma S, Suzuki H, Sun X S-Editor: Cui LJ L-Editor: A E-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Mas-Coma S, Bargues MD, Valero MA. Human fascioliasis infection sources, their diversity, incidence factors, analytical methods and prevention measures. Parasitology. 2018;145:1665-1699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lim JH, Mairiang E, Ahn GH. Biliary parasitic diseases including clonorchiasis, opisthorchiasis and fascioliasis. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33:157-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kaya M, Beştaş R, Cetin S. Clinical presentation and management of Fasciola hepatica infection: single-center experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4899-4904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Teichmann D, Grobusch MP, Göbels K, Müller HP, Koehler W, Suttorp N. Acute fascioliasis with multiple liver abscesses. Scand J Infect Dis. 2000;32:558-560. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Aksoy DY, Kerimoğlu U, Oto A, Ergüven S, Arslan S, Unal S, Batman F, Bayraktar Y. Fasciola hepatica infection: clinical and computerized tomographic findings of ten patients. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2006;17:40-45. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Lin D, Wang X, Wang Z, Li W, Zang Y, Li N. Diagnosis and management of hepatic fascioliasis mimicking intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a case report. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2017;10:1385–92. |

| 7. | Bektaş M, Dökmeci A, Cinar K, Halici I, Oztas E, Karayalcin S, Idilman R, Sarioglu M, Ustun Y, Nazligul Y, Ormeci N, Ozkan H, Bozkaya H, Yurdaydin C. Endoscopic management of biliary parasitic diseases. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1472-1478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Echenique-Elizondo M, Amondarain J, Lirón de Robles C. Fascioliasis: an exceptional cause of acute pancreatitis. JOP. 2005;6:36-39. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Kabaalioğlu A, Cubuk M, Senol U, Cevikol C, Karaali K, Apaydin A, Sindel T, Lüleci E. Fascioliasis: US, CT, and MRI findings with new observations. Abdom Imaging. 2000;25:400-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mas-Coma S, Bargues MD, Valero MA. Diagnosis of human fascioliasis by stool and blood techniques: update for the present global scenario. Parasitology. 2014;141:1918-1946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gulsen MT, Savas MC, Koruk M, Kadayifci A, Demirci F. Fascioliasis: a report of five cases presenting with common bile duct obstruction. Neth J Med. 2006;64:17-19. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Kaya M, Beştaş R, Çiçek M, Önder A, Kaplan MA. The value of micro-ELISA test in the diagnosis of Fasciola hepatica infection. Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 2013;37:23-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lin KH, Wang JH, Peng NJ. Disseminated nontuberculous mycobacterial infection mimic metastases on PET/CT scan. Clin Nucl Med. 2008;33:276-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tan GJ, Berlangieri SU, Lee ST, Scott AM. FDG PET/CT in the liver: lesions mimicking malignancies. Abdom Imaging. 2014;39:187-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sürücü E, Demir Y, Dülger AC, Batur A, Ölmez Ş, Kitapçı MT. Fasciola Hepatica Mimicking Malignancy on 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose-Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography. Mol Imaging Radionucl Ther. 2016;25:143-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Favennec L, Jave Ortiz J, Gargala G, Lopez Chegne N, Ayoub A, Rossignol JF. Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of nitazoxanide in the treatment of fascioliasis in adults and children from northern Peru. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:265-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |