Published online Feb 27, 2019. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v11.i2.242

Peer-review started: November 15, 2018

First decision: November 27, 2018

Revised: January 3, 2019

Accepted: January 27, 2019

Article in press: January 28, 2019

Published online: February 27, 2019

Processing time: 103 Days and 19.3 Hours

Only one case of liver transplantation for hepatic adenoma has previously been reported for patients with rupture and uncontrolled hemorrhage. We present the case of a massive ruptured hepatic adenoma with persistent hemorrhagic shock and toxic liver syndrome which resulted in a two-stage liver transplantation. This is the first case of a two-stage liver transplantation performed for a ruptured hepatic adenoma.

A 23 years old African American female with a history of pre-diabetes and oral contraceptive presented to an outside facility complaining of right-sided chest pain and emesis for one day. She was found to be in hemorrhagic shock due to a massive ruptured hepatic hepatic adenoma. She underwent repeated embolizations with interventional radiology with ongoing hemorrhage and the development of renal failure, hepatic failure, and hemodynamic instability, known as toxic liver syndrome. In the setting of uncontrolled hemorrhage and toxic liver syndrome, a hepatectomy with porto-caval anastomosis was performed with liver transplantation 15 h later. She tolerated the anhepatic stage well, and has done well over one year later.

When toxic liver syndrome is recognized, liver transplantation with or without hepatectomy should be considered before the patient becomes unstable.

Core tip: This case describes a rare and dramatic complication of a hepatic adenoma that resulted in both massive hemorrhage and toxic liver syndrome which could only be treated with hepatectomy. Recognition of toxic liver syndrome is essential when dealing with patients who suffer massive liver necrosis in attempts to control bleeding. Early consideration should be given to liver transplantation with or without hepatectomy before the patient becomes too unstable to proceed.

- Citation: Salhanick M, MacConmara MP, Pedersen MR, Grant L, Hwang CS, Parekh JR. Two-stage liver transplant for ruptured hepatic adenoma: A case report. World J Hepatol 2019; 11(2): 242-249

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v11/i2/242.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v11.i2.242

Hepatic adenomas are an uncommon solid tumor of the liver with an estimated incidence of 3-4 per 100000 women[1]. Hemorrhagic rupture occurs in 10%-31% of patients with hepatic adenomas, with treatment options including embolization and surgical resection with good outcomes[2,3].

One case of liver transplantation has previously been reported for patients with rupture and uncontrolled hemorrhage from a hepatic adenoma[4]. We present the case of a massive ruptured hepatic adenoma with persistent hemorrhagic shock and toxic liver syndrome which resulted in a two-stage liver transplantation. This is the first case of a two-stage liver transplantation performed for a ruptured hepatic adenoma.

A 23 year old African American female with a history of pre-diabetes and oral contraceptive use since age 11, presented to an outside facility complaining of right-upper-quadrant pain, generalized weakness, and emesis for one day. She had been in her usual state of health until that morning when she experiences the acute onset of stabbing right-upper-quadrant pain that radiated to her chest. She quickly felt nauseous and had several episodes of non-bloody emesis.

She had a past medical history significant for pre-diabetes and oral contraceptive use, but otherwise had no other medical problems and took no other medications.

She had no history of alcohol, tobacco, or drug abuse, and no family history of liver disease.

Her initial physical exam was remarkable for pallor. She was afebrile with an initial blood pressure of 96/52 mmHg and a heart rate of 126 beats per minute. Her abdominal exam was notable for right-upper-quadrant tenderness and fullness. Her cardiopulmonary exam was normal except for tachycardia. Initial labs revealed a hemoglobin 8.7 gm/dL, platelets 396 × 109/L, lactic acid 5.6 mmol/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 100 IU/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 166 IU/L, total bilirubin 0.3 mg/dL, creatinine 1.30 mg/dL, blood urea nitrogen 13 mg/dL, and bicarbonate 18 mEq/L. A urinary pregnancy test was negative.

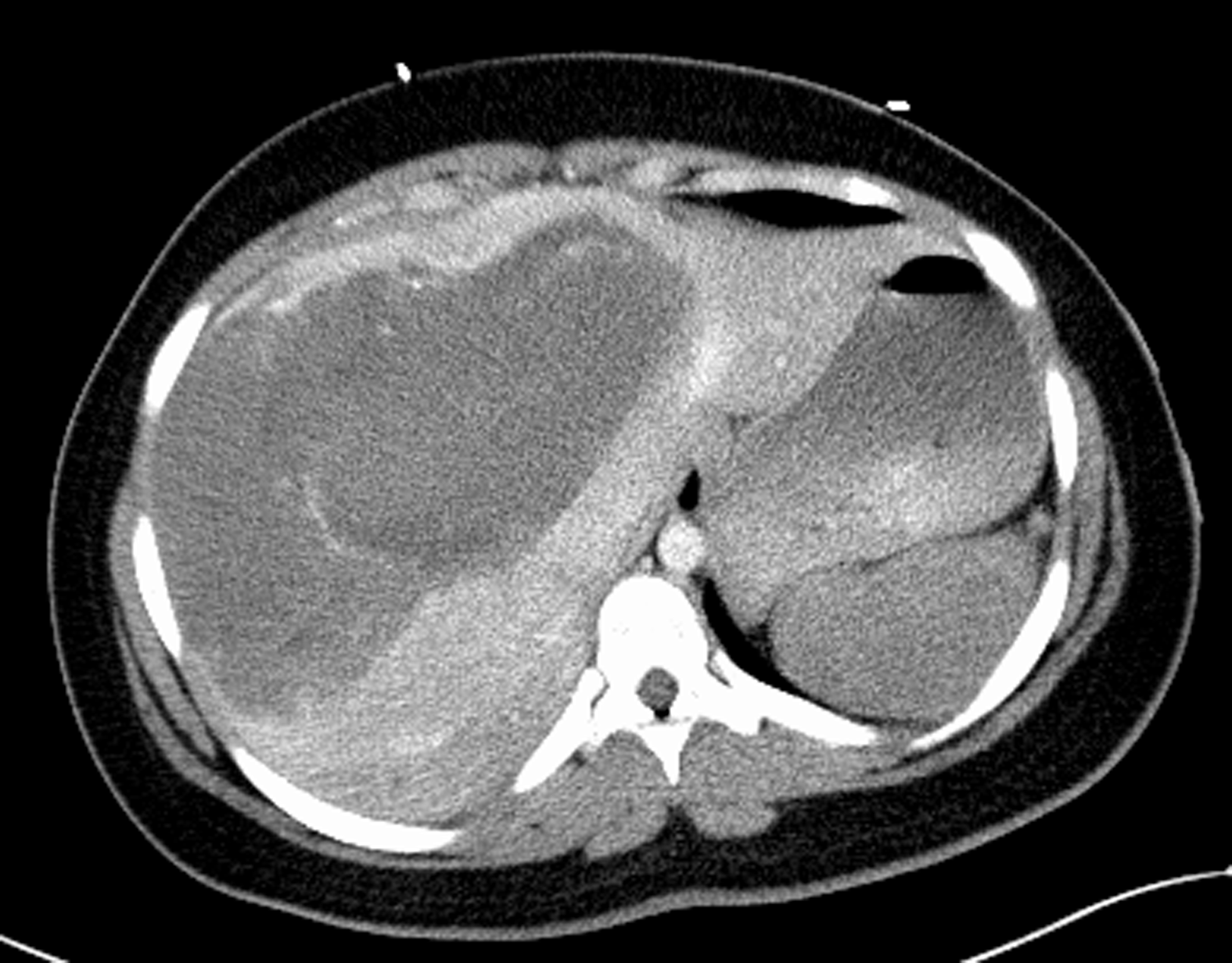

Initial imaging would include a CT of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast demonstrated a large 22 cm x 15 cm heterogenous, hypoattenuating mass encompassing nearly the entire liver. The mass demonstrated hypervascularity along the border and hyperattenuating areas, suggesting a large hemorrhagic liver mass with active hemorrhage. There was no rupture of the liver and no perihepatic, subcapsular hematoma (Figure 1). She was given preliminary diagnosis of hemorrhagic shock due to this hemorrhagic liver mass and was transferred to a second hospital for interventional radiology.

On arrival, her hemoglobin was 9.6 gm/dL after transfusion of 6 units of packed red blood cells. She underwent gel foam embolization of the right hepatic artery. However, throughout the evening she required ongoing blood transfusions. A repeat CT scan demonstrated enlargement of the intrahepatic hematoma with new intraperitoneal fluid, retroperitoneal fluid, and bilateral pleural effusion concerning for ongoing hemorrhage. She was then taken back for a mesenteric angiogram with embolization of the middle hepatic artery and repeat embolization of the right hepatic artery. During this period, her ALT increased to 1023 IU/L, AST 2287 IU/L, bilirubin 3.2 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase 506 IU/L, and lactic acid 8.3 mmol/L. She had ongoing hemodynamic instability and anuric kidney injury (creatinine 1.73 mg/dL). She was then transferred to our facility.

Here, an angiogram demonstrated active extravasation from the liver lesion (Figure 2). Repeat embolization of the entire right hepatic artery was performed. Despite these interventions and additional resuscitation, she had progressive acidosis, increasing pressor requirement, and worsening of her bilirubin, INR, and lactate (Table 1). With this rapidly deteriorating hepatic function with hemodynamic instability and renal failure, she was diagnosed with toxic liver syndrome.

| On arrival at OSH | Mid-hospitalization | Prior to transfer, at OSH | Prior to hepatectomy | 1 h post hepatectomy | 6 h post hepatectomy | Prior to transplant | 1 h after transplant | 6 h after transplant | |

| Norepinephrine (mcg/kg per minute) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.04 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 4.9 | 6.4 | 8.3 | 9.5 | 9.7 | 5.2 | 5.1 | 5 | 4.8 |

| Continuous venovenous hemodialysis | No | No | No | Adjuncts | Initiated | -100 mL/h | -150 mL/h | -200 mL/h | -130 mL/h |

| Urine Output (mL/h) | 65 | 9 | 35 | Anuric | 400 | 75 | 22 | 75 | 43 |

| Potassium (meq/L) | 4.2 | 5.4 | 6.9 | 4.5 | 4 | 3.8 | 4 | 5 | 4.5 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.22 | 1.07 | 1.73 | 1.53 | 1.45 | 0.87 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 0.84 |

| INR | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.9 | NA | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| pH | NA | 7.28 | 7.2 | 7.24 | 7.48 | 7.45 | 7.37 | 7.46 | 7.45 |

| PCO2 (torr) | NA | 26 | 34 | 35 | 31 | 34 | 37.5 | 34 | 37 |

| Total Bilirubin (mg/dL) | NA | 2.1 | 2.1 | 3.3 | NA | NA | NA | 3.9 | 3.7 |

| AST (IU/mL) | NA | 784 | 2178 | 3882 | NA | NA | NA | 2440 | 1985 |

| ALT (IU/mL) | NA | 366 | 894 | 1464 | NA | NA | NA | 1138 | 938 |

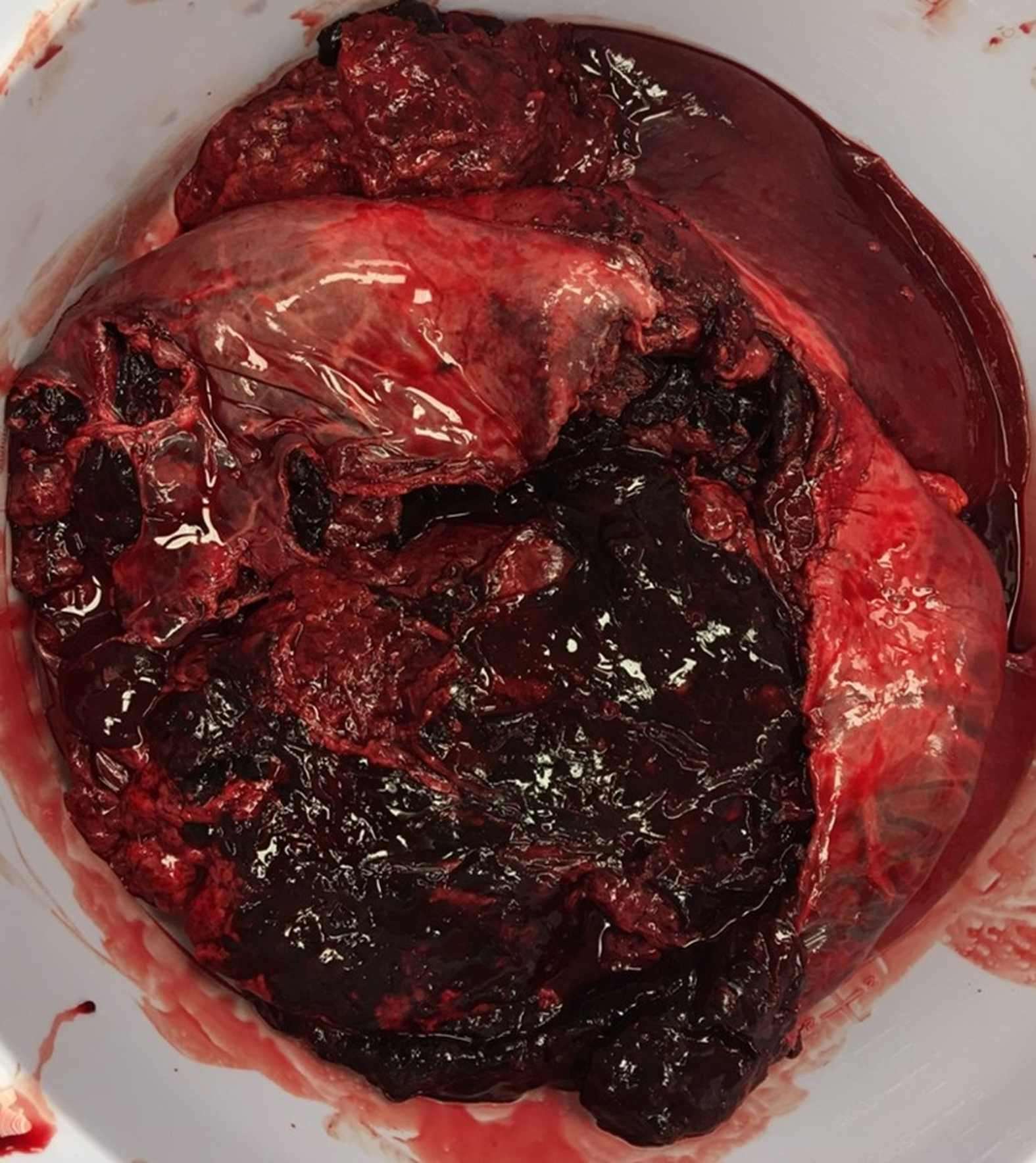

She was then taken to the operating room where the liver was found to have a rupture extending across the entire right lobe into segment 4 anteriorly, as well as a separate rupture posteriorly. Both fractures were at least 4 cm deep and more than 10 cm long with active rupture into the abdomen (Figure 3). Her right lobe and most of the left had been almost entirely replaced by coagulated blood inside of the adenoma. There was significant compressive effect of the enlarged liver on the portal vein and hepatic artery. Only a small lateral portion of segments II and III was uninvolved.

Given the size of the mass with compressive effect on adjacent vasculature, ongoing bleeding during the operation, and the ischemic injury to the remaining liver, it was decided that total hepatectomy followed by transplant would be her best chance at survival. Resection was not thought to be viable as only a small remnant of uninvolved liver remained, and this small portion was felt to already be heavily injured by preceding ischemia. The liver was then dissected off the cava. The hepatic vein stumps were oversewn and a porto-caval shunt created. Final pathology demonstrated a liver size of 34.5 cm × 22.5 cm × 8.5 cm with a red-tan hepatic adenoma measuring 30 cm × 22.5 cm × 8.5 cm. Coagulative necrosis was noted throughout tumor with intravascular foreign material consistent with embolization. The remnant liver tissue demonstrated massive necrosis with only a few remaining periportal hepatocytes.

After hepatectomy, her hemodynamics stabilized and her urine output increased. She underwent urgent liver transplant evaluation and was listed as status 1, anhepatic. She was maintained intubated on continuous venovenous hemodialysis with target sodium 145-150 mEq/L, a fresh frozen plasma drip, a 50% dextrose solution drip, empiric antibiotics, frequent calcium checks, and elevation of the head of bed. She required minimal sedation during this period with an intermittent low dose fentanyl drip. She was anhepatic for a total of 15 h before going back to the operating room for an orthotopic liver transplantation. A standard piggyback transplant was performed and a supra-celiac aortic conduit was created given the celiac dissection that had been noted earlier.

She tolerated the procedure well, and had one take-back surgery due to elevated liver function tests with findings of increased resistive indices on ultrasound. Intraoperatively, the vessels were found to be intact with some compression from abdominal wall edema which did not require any intervention other than additional volume removal. Her recovery was otherwise unremarkable. She was extubated on post-transplant day 4. She was discharged from the hospital on post-transplant day 8.

When adenomas rupture, they are managed with resuscitation to achieve hemodynamic stability and nonsurgical modalities such as embolization to control bleeding[5,6]. When conservative measure fail, partial hepatectomy or packing of the liver may be used to control the hemorrhage[3,7]. In rare cases, liver transplantation may be considered[4]. To date, 67 patients have been transplanted with hepatic adenoma as the primary diagnosis according to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (exact indications are not specified, but presumably due to size, malignant transformation, multifocality, or hemorrhage)[8]. Only one case of liver transplant for a hemorrhagic hepatic adenoma has been reported in the literature[4].

We present the case of a massive ruptured hepatic adenoma that would ultimately require a hepatectomy prior to liver transplant to manage. While the patient suffered a significant hemorrhage with rupture of her liver, the degree of hepatic and physiologic dysfunction she experienced was out of proportion solely to the degree of hemorrhage that she experienced. It is unusual for otherwise healthy patients to have such marked liver dysfunction, even in the setting of prolonged hypotension[9]. However, with the mass effect of a ruptures liver on the perihepatic vasculature, almost complete replacement of the hepatic parenchyma by adenoma and hematoma, and further damage from hemorrhagic shock and three embolization procedures, her liver parenchyma started to necrose and resulted in toxic liver syndrome.

Ringe et al[10] first coined the term toxic liver syndrome to describe patients with a non-functioning liver associated with hemodynamic instability and renal failure. The condition, though rare, is important to recognize. A recent case series from Kaltenborn et al[11] found that the cause for mortality in similar patients is not hemorrhage, which can usually be halted with packing or ligation of the porta, rather the liver necrosis and subsequent toxic liver syndrome. Cessation of hemorrhage would not have rescued this patient. In this case, the segment of remaining liver was too small to be viable, and the ongoing egress of necrotic byproducts from any retained liver would have continued to propagate her unstable state. Total hepatectomy was necessary to control hemorrhage and to relieve the physiologic sequelae of toxic liver syndrome. As a result, post-hepatectomy her heart rate normalized, her urine output tripled, and her vasoactive medications were stopped.

The use of a hepatectomy with a portocaval shunt prior to liver transplant is sometimes referred to as a two-stage liver transplant and can temporize patient awaiting an organ to transplant. Two-stage liver transplantation was first reported in 1988 and is used as a last resort for patients who are unstable due to exsanguinating hemorrhage (from trauma or an irreparable laceration due to a ruptured hepatic adenoma) or overwhelming inflammation (such as from primary graft non-function or acute liver failure)[12-14]. While early mortality for the two-stage liver transplant was as high as 60%-76% within the first year[10,15,16], the mortality in the last decade has been reported to be as low as 24% in some series[12-14].

Our patient tolerated the hepatectomy remarkably well. She had rapid hemodynamic stabilization and improvement in her urine output. During this stage, other consequences of the anhepatic state were carefully monitored. Hypoglycemia, due to a lack of hepatic gluconeogenesis, was controlled with a 50% dextrose drip. Hypocalcemia, a consequence of multiple citrate-containing blood transfusion combined with the inability to metabolize citrate, was carefully monitored and corrected[15]. Volume status and acid-base balance was managed with continuous veno-venous hemodialysis. Increased intracranial pressure was avoided by elevation of the head of the bed and maintenance of mild hypernatremia. She was transplanted 15 hours later, and was discharged within approximately one week of liver transplantation. At the time of submission, the patient continues to do well over a year from transplant and has not had to be re-hospitalized.

This case describes a rare and dramatic complication of a hepatic adenoma that resulted in both massive hemorrhage and liver dysfunction which could only be treated with hepatectomy. Recognition of toxic liver syndrome is essential when dealing with patients who suffer massive liver necrosis in attempts to control bleeding. Though embolization to control bleeding is an important first step, ultimately these patients will not be definitively managed by embolization procedures. Early consideration should be given to liver transplantation with or without hepatectomy before the patient becomes too unstable to proceed.

Toxic liver syndrome describes patients with a non-functioning liver associated with hemodynamic instability and renal failure. Mortality in these patients are not from the hemorrhage itself, rather the liver necrosis and subsequent toxic liver syndrome. A two-stage liver transplantation, or the use of a hepatectomy with a portocaval shunt prior to liver transplant, should be considered in patients with toxic liver syndrome. Anhepatic patients require careful management of hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, volume status, acid-base balance, and intracranial pressure, among other parameters. Further research is needed to determine the optimal management of anheptic patients and ways to identify the point when hepatectomy would be most useful in patients developing toxic liver syndrome.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Kapoor S, Tajiri K S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Thomeer MG, Broker M, Verheij J, Doukas M, Terkivatan T, Bijdevaate D, De Man RA, Moelker A, IJzermans JN. Hepatocellular adenoma: when and how to treat? Update of current evidence. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2016;9:898-912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Huurman VA, Schaapherder AF. Management of ruptured hepatocellular adenoma. Dig Surg. 2010;27:56-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Addeo P, Cesaretti M, Fuchshuber P, Langella S, Simone G, Oussoultzoglou E, Bachellier P. Outcomes of liver resection for haemorrhagic hepatocellular adenoma. Int J Surg. 2016;27:34-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Santambrogio R, Marconi AM, Ceretti AP, Costa M, Rossi G, Opocher E. Liver transplantation for spontaneous intrapartum rupture of a hepatic adenoma. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:508-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Marrero JA, Ahn J, Rajender Reddy K; Americal College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: the diagnosis and management of focal liver lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1328-47; quiz 1348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 285] [Article Influence: 25.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Maoz D, Sharon E, Chen Y, Grief F. Spontaneous hepatic rupture: 13-year experience of a single center. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:997-1000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Papanikolaou V, Giakoustidis D, Patsiaura K, Imvrios G, Antoniadis N, Ouzounidis N, Nikopolitidis V, Antoniadis A, Takoudas D. Management of a giant ruptured hepatocellular adenoma. Report of a case. Hippokratia. 2007;11:86-88. [PubMed] |

| 8. | US Department of Health and Human Services. Organ procurement and transplantation network (OPTN) database. Accessed Jan 3. 2019; Available from: URL: https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/. |

| 9. | Seeto RK, Fenn B, Rockey DC. Ischemic hepatitis: clinical presentation and pathogenesis. Am J Med. 2000;109:109-113. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Ringe B, Lübbe N, Kuse E, Frei U, Pichlmayr R. Total hepatectomy and liver transplantation as two-stage procedure. Ann Surg. 1993;218:3-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kaltenborn A, Reichert B, Bourg CM, Becker T, Lehner F, Klempnauer J, Schrem H. Long-term outcome analysis of liver transplantation for severe hepatic trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75:864-869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sanabria Mateos R, Hogan NM, Dorcaratto D, Heneghan H, Udupa V, Maguire D, Geoghegan J, Hoti E. Total hepatectomy and liver transplantation as a two-stage procedure for fulminant hepatic failure: A safe procedure in exceptional circumstances. World J Hepatol. 2016;8:226-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Montalti R, Busani S, Masetti M, Girardis M, Di Benedetto F, Begliomini B, Rompianesi G, Rinaldi L, Ballarin R, Pasetto A, Gerunda GE. Two-stage liver transplantation: an effective procedure in urgent conditions. Clin Transplant. 2010;24:122-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ribeiro MA, Medrado MB, Rosa OM, Silva AJ, Fontana MP, Cruvinel-Neto J, Fonseca AZ. LIVER TRANSPLANTATION AFTER SEVERE HEPATIC TRAUMA: CURRENT INDICATIONS AND RESULTS. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2015;28:286-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bustamante M, Castroagudín JF, Gonzalez-Quintela A, Martinez J, Segade FR, Fernandez A, Galban C, Varo E. Intensive care during prolonged anhepatic state after total hepatectomy and porto-caval shunt (two-stage procedure) in surgical complications of liver transplantation. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:1343-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Oldhafer KJ, Bornscheuer A, Frühauf NR, Frerker MK, Schlitt HJ, Ringe B, Raab R, Pichlmayr R. Rescue hepatectomy for initial graft non-function after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1999;67:1024-1028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |