Published online Jan 27, 2019. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v11.i1.86

Peer-review started: September 6, 2018

First decision: November 14, 2018

Revised: November 27, 2018

Accepted: January 9, 2019

Article in press: January 9, 2019

Published online: January 27, 2019

Processing time: 144 Days and 14.4 Hours

Hepatitis B virus is a viral infection that can lead to acute and/or chronic liver disease, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Hepatitis B vaccination is 95% effective in preventing infection and the development of chronic liver disease and HCC due to hepatitis B. In 2011, the Centers for Disease Control updated their guidelines recommending that adults at high-risk for hepatitis B infection be vaccinated against hepatitis B including those with diabetes mellitus (DM). We hypothesize that adults at high-risk for hepatitis B infection are not being adequately screened and/or vaccinated for hepatitis B in a large urban healthcare system.

To investigate clinical factors associated with Hepatitis B screening and vaccination in patients at high-risk for Hepatitis B infection.

We conducted a retrospective review of 999 patients presenting at a large urban healthcare system from 2012-2017 at high-risk for hepatitis B infection. Patients were considered high-risk for hepatitis B infection based on hepatitis B practice recommendations from the Center for Disease Control. Medical history including hepatitis B serology, concomitant medical diagnoses, demographics, insurance status and social history were extracted from electronic health records. Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify clinical risk factors independently associated with hepatitis B screening and vaccination.

Among the 999 patients, 556 (55.7%) patients were screened for hepatitis B. Of those who were screened, only 242 (43.5%) patients were vaccinated against hepatitis B. Multivariate regression analysis revealed end-stage renal disease [odds ratio (OR): 5.122; 2.766-9.483], alcoholic hepatitis (OR: 3.064; 1.020-9.206), and cirrhosis or end-stage liver disease (OR: 1.909; 1.095-3.329); all P < 0.05 were associated with hepatitis B screening, while age (OR: 0.785; 0.680-0.906), insurance status (0.690; 0.558-0.854), history of DM (OR: 0.518; 0.364-0.737), and human immunodeficiency virus (OR: 0.443; 0.273-0.718); all P < 0.05 were instead not associated with hepatitis B screening. Of the adults vaccinated for hepatitis B, multivariate regression analysis revealed age (OR: 0.755; 0.650-0.878) and DM were not associated with hepatitis B vaccination (OR: 0.620; 0.409-0.941) both P < 0.05.

Patients at high-risk for hepatitis B are not being adequately screened and/or vaccinated. Improvements in hepatitis B vaccination should be strongly encouraged by all healthcare systems.

Core tip: This is a retrospective study evaluating clinical factors associated with Hepatitis B virus (HBV) screening and vaccination in high-risk adults. Among the 999 high-risk adults included in this study, 556 (55.7%) adults were screened for HBV. Of those who were screened, only 242 (43.5%) adults were vaccinated against HBV. Clinical factors such as End Stage Renal Disease, and cirrhosis were associated with HBV screening, while diabetes mellitus (DM) was not. Patients with DM were less likely to undergo HBV vaccination. HBV vaccination is highly effective in preventing HBV-related liver disease and its sequelae. Increasing HBV vaccination in all high-risk adults should be strongly encouraged by all healthcare systems.

- Citation: Ayoola R, Larion S, Poppers DM, Williams R. Clinical factors associated with hepatitis B screening and vaccination in high-risk adults. World J Hepatol 2019; 11(1): 86-98

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v11/i1/86.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v11.i1.86

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a major cause of acute and chronic liver disease (CLD) both in the United States and worldwide. More than 350 million people worldwide are infected with HBV, of whom approximately 1.4 million reside in the United States[1,2]. HBV is one of the leading causes of cirrhosis and the most common cause for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), accounting for 50% of all HCC cases and virtually all childhood cases of this condition[3].

The primary approach to HBV prevention is immunization through vaccination. The vaccine is usually given as 2, 3, or 4 injections over a 6 mo period. With the advent of a highly effective HBV vaccine, HBV infection rates have decreased from an estimated 13.8 cases per 100000 in 1987 to roughly 1.5 cases per 100000 in 2007 in the United States[4-7]. In 2006, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommended HBV vaccination for unvaccinated adults who are at high-risk for HBV infection[8]. These indications were expanded in 2011 to include patients with diabetes mellitus (DM), patients between 19 and 59 years of age, and those greater than 60 years of age at the discretion of the supervising clinician (Table 1)[9].

| High-risk conditions for HBV infection |

| People whose sex partners have hepatitis B |

| Sexually active persons who are not in a long-term monogamous relationship |

| Persons seeking evaluation or treatment for a sexually transmitted disease |

| Men who have sexual contact with other men |

| People who share needles, syringes, or other drug-injection equipment |

| People who have household contact with someone infected with the hepatitis B virus |

| Health care and public safety workers at risk for exposure to blood or body fluids |

| Residents and staff of facilities for developmentally disabled persons |

| Persons in correctional facilities |

| Victims of sexual assault or abuse |

| Travelers to regions with increased rates of hepatitis B |

| People with chronic liver disease, kidney disease, HIV infection, or diabetes |

| Anyone who wants to be protected from hepatitis B |

HBV vaccination is the most effective measure to prevent hepatitis B infection and its sequelae, including acute liver failure, cirrhosis, HCC, and overall liver-related death. However, HBV vaccination among high-risk patients has been limited by a number of factors including a lack of appropriate physician implementation of CDC recommendations, as well as inadequate insurance coverage to pay for patient vaccination. Most health insurance plans cover recommended vaccines for adults at little or no cost, but many people in the United States remain without health insurance coverage. A 2012 US National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) study on vaccination coverage (defined as those having received at least the three recommended vaccination doses) reported only 24.6% of adults aged ≥ 19 yr being vaccinated (16.5% among adults aged ≥ 50 yr) with rates of 42% in adults deemed at high-risk[9,10]. Despite CDC recommendations and significant public health efforts, HBV vaccination rates increased by less than 5% between 2004 and 2009, in the United States[11]. Since the addition of DM as a vaccination criterion in 2011, rates of HBV vaccination in the high-risk population is unclear. Previous epidemiological studies on HBV vaccination rates have also demonstrated that underrepresented high-risk patient populations have been noted to have the highest prevalence of HBV infection[12].

The purpose of this study was to perform a retrospective chart review of patients at high-risk for HBV infection from 2012-2017 in a large, urban safety-net hospital and tertiary care center. Our study had several aims: (1) To determine serologically evident HBV vaccination and screening rates in adults at high-risk for HBV; (2) to identify clinical factors significantly associated with screening and vaccination rates; and (3) to identify the key baseline characteristics of these individuals.

A retrospective cohort study was performed using our center’s electronic medical record (EMR) of randomly selected patients presenting to our health system between 2012 and 2017 who were considered at high-risk for HBV. Our health system is a large, academic medical center that incorporates a safety-net hospital that serves a diverse patient population in an urban setting. The most recent CDC guidelines were used to determine medical conditions considered high-risk for HBV infection (Table 1). Patients were included in the study if a high-risk condition or activity was noted in the EMR. A patient list was generated using ICD-10 identifiers, with subject demographics including clinical history obtained via individual chart review. Patients from both inpatient and outpatient settings were included. Patients were excluded if a high-risk ICD-10 designator was not documented in the medical history, or if the patient had previously contracted HBV (positive serology for hepatitis B surface antigen). Data accrual was terminated following review of 1100 individual patient records.

The final study population was stratified into two cohorts: a screening cohort and a vaccination cohort. The screening cohort consisted of all patients at high-risk for HBV as determined by the study inclusion criteria. Patients were considered to have undergone HBV screening if HBV serology [hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc) and hepatitis surface B surface antibody (anti-HBs)] was documented in the EMR. Patients without HBsAg, anti-HBc, and anti-HBs in our EMR were not considered to have been screened. Demographic and clinical factors were compared between patients who were screened for HBV versus those who were not in order to identify factors associated with screening. The vaccination cohort consisted of the subset of patients in the screening cohort who had HBV serology on file. Patients were considered to have undergone HBV vaccination if the anti-HBs was positive, and the HBsAg and anti-HBc were negative. Patients with negative anti-HBs, HBsAg, and anti-HBc were not considered vaccinated. As with the screening cohort, demographic and clinical factors were compared between patients who were vaccinated for HBV and those who were not in order to identify factors associated with vaccination.

Data are presented as percentages for categorical variables and medians for non-parametric continuous variables. Differences in proportions were determined using the chi-square test with Yates correction factor or the Fisher exact test, as appropriate. Differences in continuous variables were determined using the Mann-Whitney U-test. Factors found significant (P < 0.05) on univariate analysis were inputted into a multivariate logistic regression with the dichotomous dependent variable (screening or vaccination) coded as 1. Dummy variables were used to code categorical variables. For regression purposes, health insurance coverage was coded as follows “0” for private insurance, “1” for Medicare, “2” for Medicaid, and “3” for uninsured or other types of coverage. Age was coded by increasing deciles. BMI was grouped into increasing 5 kg/m2 units as listed and coded as integers. Missing data fields were left blank. Logistic regression results are reported as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. The Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic was used to test model goodness-of-fit. A biomedical statistician performed the statistical review of this study. Data analysis was completed using Sigmaplot 12.0 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA, United States). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of NYU Langone Health (s16-01837).

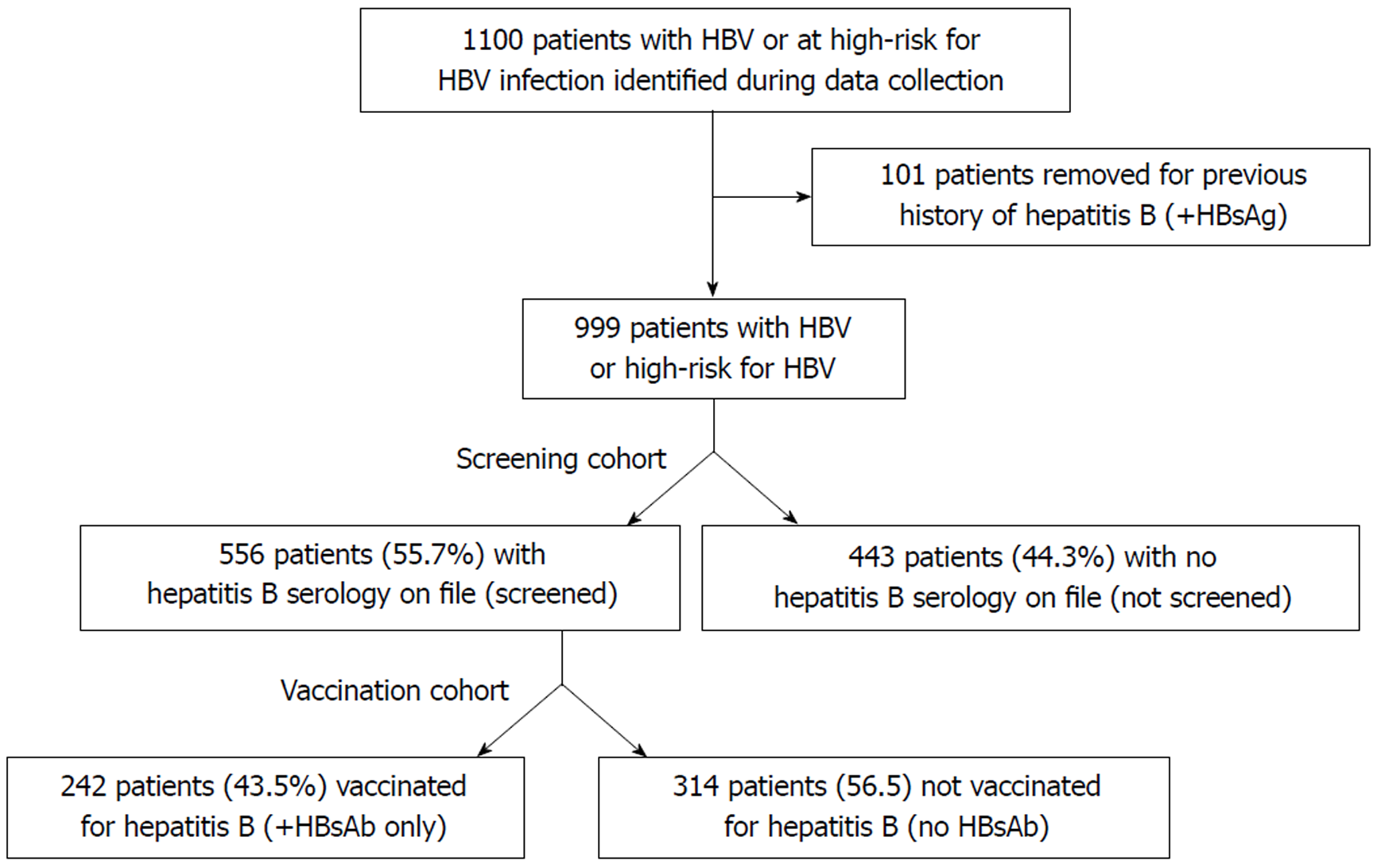

A total of 1,100 patients were identified during the data collection period, of which 101 were excluded due to evidence of prior HBV infection (i.e., positive HBsAg). Of the remaining 999 patients, 556 (55.7%) patients had been screened for hepatitis B and 443 patients (44.3%) had not been screened (“screening cohort”; Figure 1). Demographics for the screening cohort are listed in Table 2, showing that a higher proportion of patients were male (60.6%), between 50-70 yr of age (63.1%), and obese (BMI > 25 kg/m2; 66.4%). Almost half of the study cohort was non-white (46.5%), and 40.6% did not have private health insurance.

| Screening cohort | Vaccination cohort | |||||||

| Demographic | Entire screening cohort (n = 999) | Screened for HBV (n = 556) | Not screened for HBV (n = 443) | P-value | Entire vaccination cohort (n = 556) | Vaccinated against HBV (n = 242) | Not vaccinated against HBV (n = 314) | P-value |

| Male | 60.6% | 59.7% | 61.6% | 0.583 | 59.7% | 59.5% | 59.9% | 0.999 |

| Age | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||

| < 40 | 4.9% | 7.9% | 1.1% | 7.9% | 12.8% | 4.1% | ||

| 41-50 | 6.7% | 11.5% | 0.7% | 11.5% | 14.1% | 9.6% | ||

| 51-60 | 26.4% | 22.3% | 31.6% | 22.3% | 24.4% | 20.7% | ||

| 61-70 | 36.7% | 28.2% | 47.4% | 28.2% | 25.2% | 30.6% | ||

| 71-80 | 14.6% | 15.6% | 13.3% | 15.6% | 12.4% | 18.2% | ||

| > 80 | 10.6% | 14.4% | 5.9% | 14.4% | 11.2% | 16.9% | ||

| BMI | 0.028 | 0.047 | ||||||

| < 20 | 7.0% | 8.7% | 4.8% | 8.7% | 11.9% | 6.3% | ||

| 20-24.9 | 26.6% | 29.0% | 23.5% | 29.0% | 29.8% | 28.3% | ||

| 25-29.9 | 32.7% | 31.5% | 34.2% | 31.5% | 31.2% | 31.8% | ||

| 30-34.9 | 20.6% | 19.0% | 22.5% | 19.0% | 19.3% | 18.9% | ||

| > 35 | 13.1% | 11.7% | 14.9% | 11.7% | 7.8% | 14.7% | ||

| Race | 0.006 | 0.001 | ||||||

| White | 53.5% | 51.9% | 48.1% | 49.8% | 36.1% | 63.9% | ||

| Black | 17.1% | 61.4% | 38.6% | 18.9% | 55.2% | 44.8% | ||

| Hispanic | 11.7% | 67.5% | 32.5% | 14.2% | 41.8% | 58.2% | ||

| Other | 17.7% | 53.7% | 46.3% | 17.1% | 53.7% | 46.3% | ||

| Insurance | < 0.001 | 0.488 | ||||||

| Private | 59.4% | 59.5% | 40.5% | 63.5% | 41.4% | 58.6% | ||

| Medicare | 30.1% | 53.5% | 46.5% | 29.0% | 46.0% | 54.0% | ||

| Medicaid | 6.8% | 45.6% | 54.4% | 5.6% | 51.6% | 48.4% | ||

| Uninsured | 3.7% | 29.7% | 70.3% | 2.0% | 54.5% | 45.5% | ||

High-risk medical conditions as determined by the CDC are listed in Table 3, revealing that chronic kidney disease (CKD) (48.1%), DM (46.8%), and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) (41.3%) were highly enriched in the study population. Hemoglobin A1c was available for 499 (49.9%) patients, with a median A1c of 6.5% (25-75th percentile: 5.6%-7.7%). CLD was present in 25.7% of patients, including 10.3% with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection (i.e., a positive hepatitis C virus antibody [HCV Ab] with a detectable viral load on RNA PCR assay), and 10.1% of patients were noted to have non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Cirrhosis was reported in 10.6% of patients (median MELD: 16; 25-75th percentile: 10-21), with 70 patients (7.0%) currently listed for liver transplant. A total of 75 (7.5%) expired at the end of data collection period, including 13 from liver-related deaths. Most patients (76.0%) had at least two or more high-risk conditions or activities as defined by the CDC.

| Screening cohort | Vaccination cohort | |||||||

| High risk condition | Entire screening cohort (n = 999) | Screened for HBV (n = 556) | Not screened for HBV (n = 443) | P-value | Entire vaccination cohort (n = 556) | Vaccinated against HBV (n = 242) | Not vaccinated against HBV (n = 314) | P-value |

| Intravenous drug use | 1.9% | 0.9% | 3.2% | 0.018 | 0.9% | 1.2% | 0.6% | 0.769 |

| Men who have sex with Men | 5.0% | 4.0% | 6.3% | 0.120 | 4.0% | 5.8% | 2.5% | 0.085 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 48.1% | 64.6% | 27.5% | < 0.001 | 64.6% | 73.1% | 58.0% | < 0.001 |

| End stage renal disease (dialysis) | 41.3% | 59.2% | 19.0% | < 0.001 | 59.2% | 69.0% | 51.6% | < 0.001 |

| Chronic liver disease | 25.7% | 26.4% | 24.8% | 0.614 | 26.4% | 21.5% | 30.3% | 0.026 |

| Alcohol hepatitis | 3.2% | 4.9% | 1.1% | 0.002 | 4.9% | 2.9% | 6.4% | 0.091 |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.799 | 0.5% | 0% | 1.0% | 0.347 |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 0.7% | 0.2% | 1.4% | 0.067 | 0.2% | 0% | 0.3% | 0.896 |

| Cryptogenic liver | 0.6% | 0.7% | 0.5% | 0.895 | 0.7% | 0.8% | 0.6% | 0.807 |

| Hemochromatosis | 0.2% | 0% | 0.5% | 0.382 | 0% | 0% | 0% | n/a |

| Hepatitis C | 10.3% | 9.4% | 11.5% | 0.312 | 9.4% | 8.9% | 9.9% | 0.799 |

| Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease | 10.1% | 11.2% | 8.8% | 0.264 | 11.2% | 7.9% | 13.7% | 0.042 |

| Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis | 1.6% | 1.6% | 1.6% | 0.837 | 1.6% | 0.8% | 2.2% | 0.337 |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 0.7% | 1.1 | 0.2% | 0.221 | 1.1% | 0.8% | 1.3% | 0.926 |

| End stage liver disease (cirrhosis) | 10.6% | 12.8% | 7.9% | 0.017 | 12.8% | 9.5% | 15.3% | 0.058 |

| Human immunodeficiency virus | 14.3% | 7.9% | 22.3% | < 0.001 | 7.9% | 9.9% | 6.4% | 0.168 |

| High risk sexual behavior | 22.5% | 20.5% | 25.1% | 0.102 | 20.5% | 23.6% | 18.2% | 0.145 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 46.8% | 43.0% | 51.7% | 0.007 | 43.0% | 37.2% | 47.5% | 0.019 |

Cardiovascular risk factors and other major comorbid conditions are listed in Table 4, showing that hypertension (59.6%), dyslipidemia (43.2%; median LDL: 80; 25-75th percentile: 57-107), and coronary artery disease (CAD; 21.1%) were also common in our study population. A total of 39.1% of patients had a current or former smoking history, including 6.6% who were active tobacco users. As expected in underserved patient populations, only 32.6% of patients had seen a primary care provider within the previous year, and only 25.8% had been evaluated by a gastroenterologist within the past year.

| Screening cohort | Vaccination cohort | |||||||

| Comorbidity | Entire screening cohort (n = 999) | Screened for HBV (n = 556) | Not screened for HBV (n = 443) | P-value | Entire vaccination cohort (n = 556) | Vaccinated against HBV (n = 242) | Not vaccinated against HBV (n = 314) | P-value |

| Acute liver failure | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.782 | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.597 |

| Dyslipidemia | 43.2% | 41.9% | 44.9% | 0.373 | 41.9% | 38.8% | 44.3% | 0.231 |

| Hypertension | 59.6% | 63.0% | 55.3% | 0.017 | 62.9% | 68.2% | 58.9% | 0.031 |

| Coronary artery disease | 21.1% | 24.3% | 17.2% | 0.008 | 24.3% | 26.0% | 22.9% | 0.455 |

| Chronic heart failure | 10.2% | 12.2% | 7.7% | 0.024 | 12.2% | 11.6% | 12.7% | 0.775 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 5.6% | 5.6% | 5.6% | 0.927 | 5.6% | 4.1% | 6.7% | 0.265 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 5.2% | 6.1% | 4.1% | 0.191 | 6.1% | 4.5% | 7.3% | 0.239 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 7.2% | 8.6% | 5.4% | 0.067 | 8.6% | 11.2% | 6.7% | 0.088 |

| Psychiatric disorder | 10.0% | 9.2% | 11.1% | 0.378 | 9.2% | 8.7% | 9.6% | 0.836 |

| Current tobacco user | 6.6% | 4.9% | 8.8% | 0.018 | 4.9% | 3.7% | 5.7% | 0.370 |

| Current Alcohol use | 29.0% | 31.3% | 26.2% | 0.090 | 31.3% | 29.8% | 32.5% | 0.551 |

| Cancer (any) | 18.7% | 19.1% | 18.3% | 0.816 | 19.1% | 12.8% | 23.9% | 0.001 |

Demographic and clinical factors in the screening cohort were compared between those who had been successfully screened for hepatitis B (n = 556; 55.7%) and those who had not been screened (n = 443; 44.3%). Univariate analysis revealed that patients who had been screened for HBV were more likely to be under 50 yr of age and have a BMI of less than 25.0 kg/m2 (P < 0.05; Table 2). Race was significantly associated with screening status (P = 0.006), ranging from 67.5% in Hispanic patients to 51.9% in white patients (Table 2). Insurance status was also significantly associated with screening (P < 0.001), peaking at 59.5% in individuals with private health insurance to less than 30% in uninsured patients (Table 2).

High-risk medical conditions are listed in Table 3, revealing that HBV screening was significantly more common in patients with CKD or ESRD (both P < 0.001). Screening was also more frequent in patients with major cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, CAD, or congestive heart failure (all P < 0.05; Table 4). In contrast, a history of intravenous drug use (3.2% vs 0.9%), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (22.3% vs 7.9%), or current tobacco use (8.8% vs 4.9%, all P < 0.05) were significantly more frequent in patients who had not been screened for HBV, suggesting a bias against HBV screening in patients with a history of high-risk activities such as polysubstance abuse.

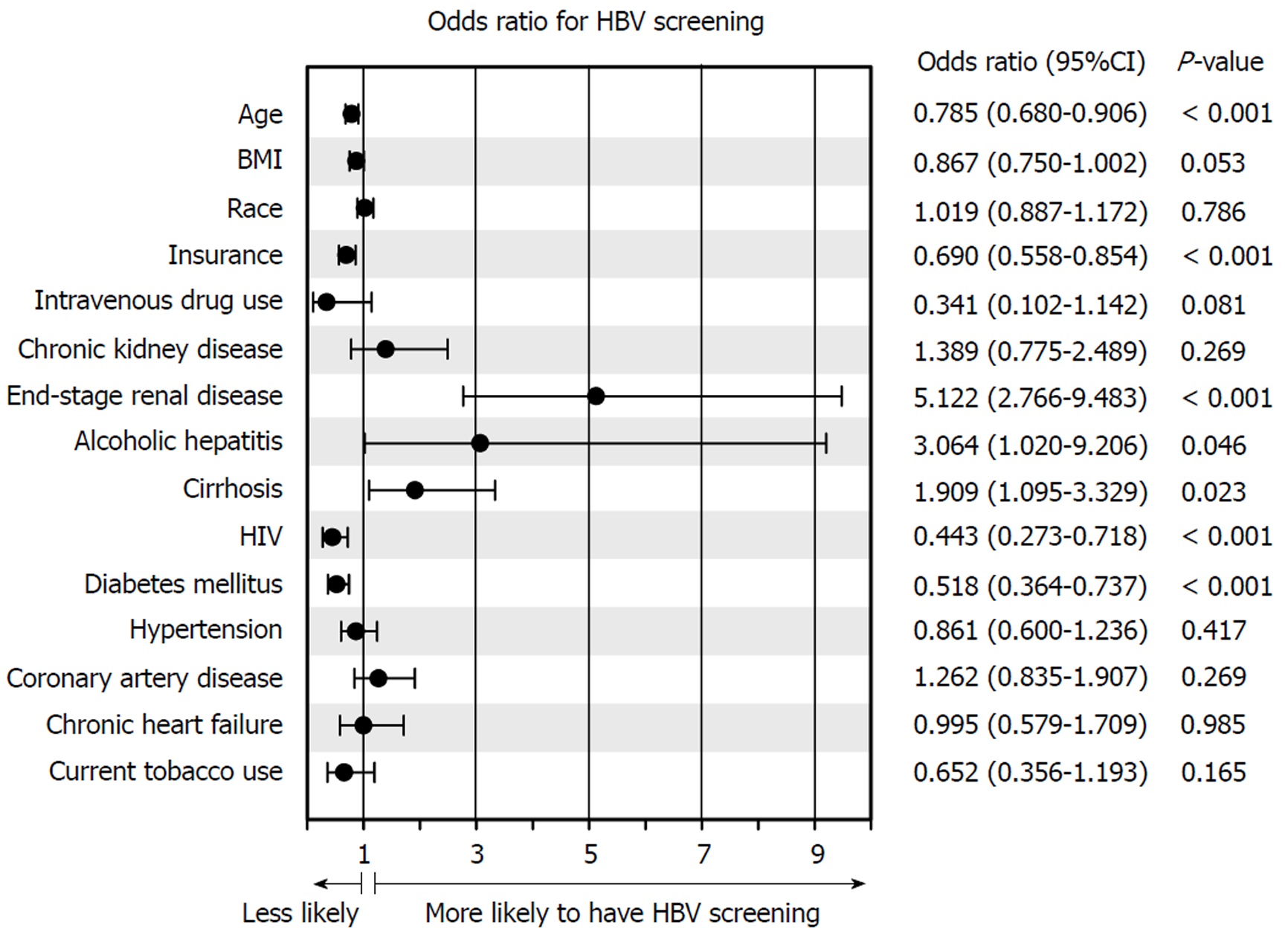

Multivariate analysis revealed that medical conditions such as ESRD [odds ratio (OR): 5.122; 2.766-9.483], alcoholic hepatitis (OR: 3.064; 1.020-9.206), and cirrhosis (OR: 1.909; 1.095-3.329) were positively associated with HBV screening (Figure 2). Demographics including age (OR: 0.785; 0.680-0.906) or insurance status (OR: 0.690; 0.558-0.854), and chronic medical conditions such HIV (OR: 0.443; 0.273-0.718), and DM (OR: 0.518; 0.364-0.737) were inversely correlated with screening (all P < 0.05), suggesting that socioeconomic factors strongly impact likelihood of screening. The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was not significant (P = 0.116), indicating that the regression fit the data. Patients who were screened for HBV were also significantly more likely to have undergone HCV screening, hepatitis A vaccination, or have a documented hepatitis A serology on file (all P < 0.05; Table 5). These patients were also more likely to have been evaluated by primary care providers, emergency department personnel, or gastroenterologists within the past year (all, P < 0.001). MELD score was significantly higher in patients who had undergone HBV screening (median: 16 vs 12), and these patients tended to succumb more frequently to all-cause (11.3% vs 2.7%, P < 0.001) and liver-related mortality (2.0% vs 0.5%, P = 0.067 trend).

| Screening cohort | Vaccination cohort | |||||

| Variate | Screened for HBV (n = 556) | Not screened for HBV (n = 443) | P-value | Vaccinated against HBV (n = 242) | Not vaccinated against HBV (n = 314) | P-value |

| HCV serology | 82.4% | 19.2% | < 0.001 | 78.5% | 85.4% | 0.047 |

| HCV infection | 9.4% | 11.5% | 0.312 | 12.1% | 10.2% | 0.629 |

| Hepatitis A vaccination | 36.0% | 0% | < 0.001 | 51.7% | 23.9% | < 0.001 |

| Hepatitis A (HAVab IgM or IgG) | 26.1% | 4.3% | 0.002 | 27.9% | 24.7% | 0.616 |

| 1 or more primary care visit per year | 43.8% | 30.9% | < 0.001 | 38.1% | 48.1% | 0.030 |

| 1 or more emergency department visit per year | 56.6% | 26.7% | < 0.001 | 57.0% | 56.4% | 0.956 |

| 1 or more gastroenterology visit per year | 35.4% | 19.4% | < 0.001 | 31.9% | 38.0% | 0.166 |

| MELD score (median; 25-75th percentile) | 16 (11-23) | 12 (8-20) | 0.019 | 16 (11-22) | 17 (12-24) | 0.586 |

| All-cause mortality | 11.3% | 2.7% | < 0.001 | 10.7% | 11.8% | 0.804 |

| Liver-related mortality | 2.0% | 0.5% | 0.067 | 2.4% | 1.6% | 0.662 |

| Listed for liver-transplant | 8.1% | 5.6% | 0.167 | 6.6% | 9.2% | 0.333 |

Of the 556 patients who had been screened for HBV, a total of 242 (43.5%) patients had been vaccinated for HBV, while 314 (56.5%) patients had not been vaccinated (“vaccination cohort”; Figure 1). Demographic information is listed in Table 2, revealing that most patients were male (59.7%), obese (BMI > 25 kg/m2; 62.2%), and 19.4% were under 50 years of age. The vaccination cohort was socioeconomically diverse with 50.2% non-white and 36.5% without private medical insurance. Similar to the screening cohort, the vaccination cohort was characterized by a large burden of cardiovascular and other high-risk medical conditions including 64.6% with CKD, 26.4% with CLD 20.5% with high-risk sexual behavior, and 7.9% with HIV (Tables 2 and 3).

Clinical information was compared between those who had been vaccinated against HBV vs those who had not been vaccinated. Univariate analysis revealed that HBV vaccination was more frequently performed in non-obese patients (BMI < 25 kg/m2; 41.7% vs 34.6%) and those younger than 50 years of age (26.9% vs 13.7%, both P < 0.05). Race significantly impacted vaccination status, with HBV vaccination ranging from 55.2% in black patients to only 36.1% of white patients (P = 0.001). Vaccination remained low among all insurance classes (range: 41.4%-54.5%) and was not affected by type of coverage (P > 0.05). Moreover, vaccination was significantly more common in patients with hypertension, CKD, or ESRD, while less common in patients with CLD, NAFLD, DM, or cancer (all P < 0.05; Tables 3 and 4).

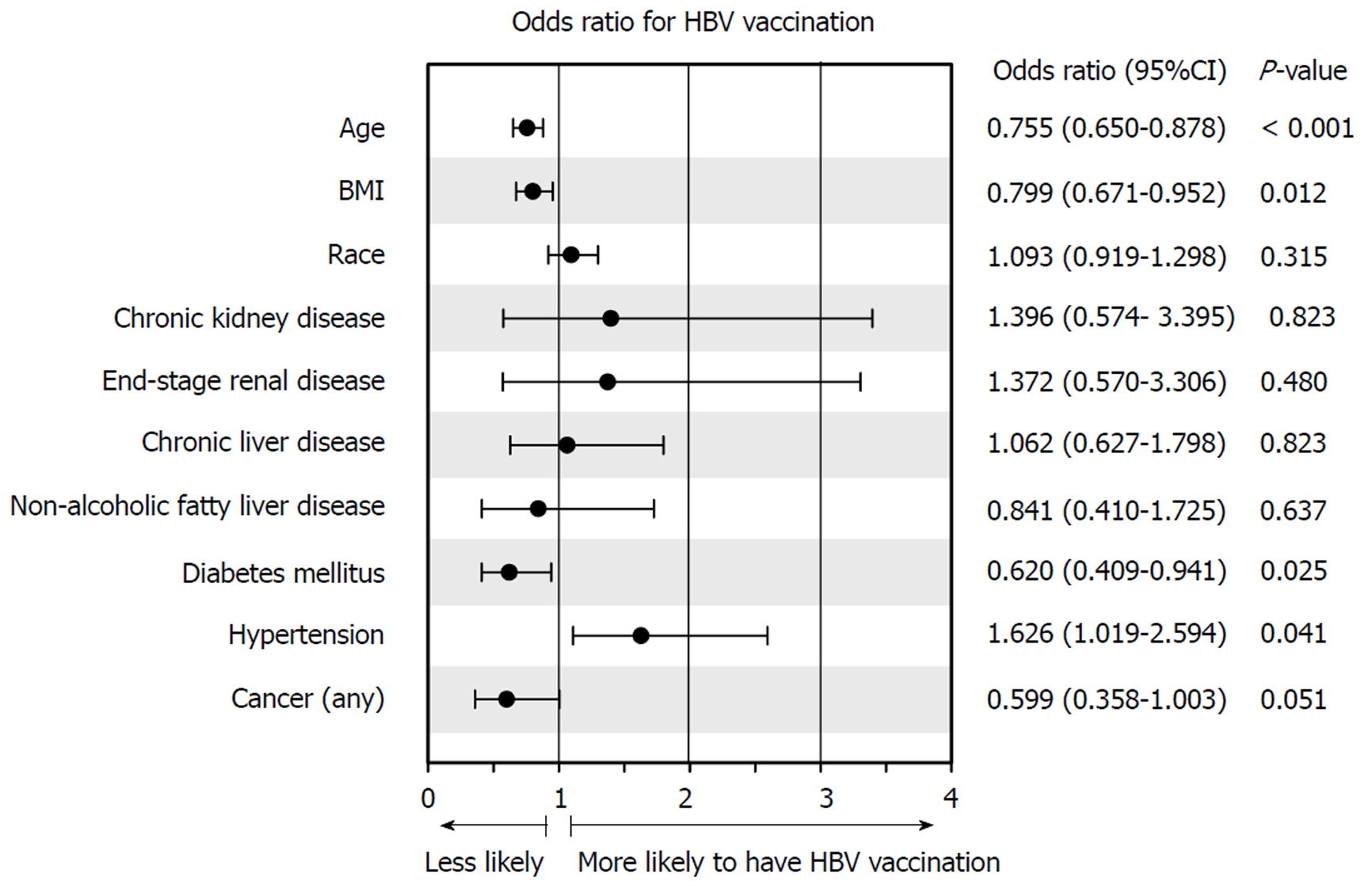

Multivariate analysis revealed that hypertension (OR: 1.626; 1.019-2.594) was positively associated with HBV vaccination, while DM (OR: 0.620; 0.409-0.941) and BMI (OR: 0.799; 0.671-0.952) were inversely correlated with vaccination (all P < 0.05; Figure 3). Older age (OR: 0.755; 0.650-0.878; P < 0.05) was again inversely correlated with vaccination, further suggesting that patient demographics are an important clinical factor affecting HBV management. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test was not significant (P = 0.470), indicating that the regression fit the data.

Additional data on gastrointestinal history and healthcare utilization is listed in Table 5. MELD score (median: 16 vs 17), all-cause mortality (10.7% vs 11.8%), and liver-disease specific mortality (2.4% vs 1.6%, all P > 0.05) were not significantly different between patients with or without HBV vaccination.

The CDC recommends all individuals at high-risk for HBV infection undergo vaccination. Updated CDC guidelines on HBV management in 2011 greatly increased the number of eligible patients who should undergo HBV vaccination by expanding vaccination criteria to include most patients with a history of DM. Despite this, only 55.7% of high-risk patients were screened for HBV, and only 43.5% were appropriately vaccinated against infection. Socioeconomic factors such as age and insurance status significantly affected HBV management, as well as high-risk medical conditions including HIV. DM was a significant risk factor in patients who were suboptimally managed, suggesting a failure to fully implement new CDC recommendations in clinical practice. Results of a 2012 NHIS study found similar HBV vaccination rates amongst high-risk individuals, but despite additional recommendations by the CDC, as well as a 6-year time lapse, there has not been a significant increase in HBV vaccination during this period. One would expect that vaccination rates over time would increase as CDC HBV vaccination awareness had increased. This may be due to lack of awareness by physicians, and the high demand of quality patient care particularly in underserved populations. More awareness regarding HBV vaccination recommendations is needed for both primary care physicians and gastroenterology subspecialists.

As our demographics represent a diverse cohort typical of many large, urban safety-net hospitals, our study identifies a significant disparity in HBV management that disproportionately affects the most vulnerable and underserved patient population. Older patients and patients with DM were less likely to be screened and vaccinated for HBV, while patients with cardiac or renal comorbidities such as chronic kidney disease and hypertension were more frequently evaluated for HBV. This result is likely related to the necessity of hepatitis B serology before initiation of hemodialysis, as well as the significant association between renal and cardiac disease.

The efficacy of HBV vaccination in a high-risk population has been found to be greater than 90% in adults[13,14]. Despite the CDC and Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) long-standing recommendations to vaccinate high-risk adult populations, national HBV vaccination coverage rates have remained low[9,11,15]. Compared with high-risk vaccination coverage in the United States, reported to be around 42% in 2012, these rates vary greatly in other industrialized countries from 14%-38% in England in 2004, 25%-45% in France in 2004, and 6%-29% in the Netherlands in 2007. Compared with previously published vaccination rates in the US, our results were similar or lower[16-18].

From 2010–2015, HBV vaccination coverage decreased overall in adults 19 years of age or older, and coverage still remains suboptimal, minimally changed from previous years, with room for improvement, particularly amongst higher-risk populations, especially based upon current recommendations[10].

In 2011, the CDC and ACIP created new recommendations for HBV vaccination for all unvaccinated adults with DM under 60 years of age. Vaccination of patients greater than 60 years of age was advised at the discretion of individual health care providers. People with both type 1 and type 2 DM have higher rates of HBV than the general population and are at additional risk because of shared blood glucose meters, fingerstick devices, and other diabetes-care equipment such as syringes or insulin pens[9,19]. HBV outbreaks in people with DM in assisted living, long-term care facilities, and nursing homes have been seen related to inadequate hand hygiene between fingerstick procedures and the maintenance of sterility of blood glucose monitoring and podiatric equipment and supplies. Consistent with these studies, we report that patients with DM had lower vaccination rates than those with similar high-risk medical conditions. Previous NHIS data from a 2014-15 collection period reports that vaccination coverage for DM patients was 24.4% for those aged 19–59 years and 12.6% for those 60 years of age and older[10]. Our data and those from other studies highlight the need to educate both patients and clinicians regarding the increased risk of HBV transmission among patients with DM and the need to increase HBV screening and vaccination in this higher-risk subpopulation.

Given the high prevalence of HBV infections in high-risk patients, it is reasonable to screen patients for hepatitis B prior to administering the vaccine[20]. Although screening is currently not universally recommended, it can aid in identifying patients who are already immune to HBV, and help distinguish between those who may or may not require vaccination, minimizing unnecessary vaccinations. One challenge in HBV screening is its cost effectiveness.

Post-vaccination screening can also identify those who do not seroconvert after completing the requisite vaccination series. Post-vaccination screening may be indicated in CLD as superimposed viral hepatitis B is associated with morbidity and mortality in these patients[21,22]. Patients with CLD who receive HBV vaccination have generally lower rates of seroconversion compared to otherwise healthy adults, which may be as low as 18% in patients with advanced fibrosis[23-25]. Post-vaccination screening is justified in patients with CLD and a repeat course of HBV vaccination should be considered in those who initially fail to seroconvert.

Despite the safety and well-documented benefits, rates of HBV immunization have not increased as expected. Different actions can be implemented to improve vaccination coverage. This may start with educating patients and physicians about the importance of immunization and the diseases it prevents, staying updated with current vaccination guidelines, identifying barriers to vaccination including cost, and addressing patient misconceptions. Implementing population-based immunization registries can provide access to comprehensive immunization records for patients at the community level. These registries have been shown to be effective at improving immunization rates due to their various capabilities.

Vaccination reminder-recall systems are another cost-effect method to notify adults who should undergo immunization. Many EMRs can implement standing orders, assisting healthcare professionals with identifying patient who may benefit from additional screening. These prompts may consist of electronic pop-ups in the EMR that automatically display alerts to help notify viewers that the patient is due or overdue for vaccination.

A strength of our study is an emphasis on the determination of clinical factors that may be used to identify patients in the inpatient and outpatient setting who are likely to benefit from further review of their HBV vaccination record. Previous population-based HBV vaccination and screening data have been based on surveys, and our study population is more representative of real-world data based on patient serologies in underserved urban populations. Previously reported survey-based 2012 NHIS HBV vaccination rates in high-risk adults were similar but did not include patients with DM. Our study also included anti-HBc data in the serologic panel to differentiate between immunity due to vaccination compared with prior HBV infection.

This retrospective study is subject to a number of limitations. High-risk factors in patients are often underreported by patients (and physicians) or may not be consistently documented. Patients may frequently hesitate to report high-risk activities or history such as intravenous drug use or high-risk sexual behavior, thereby underestimating the proportion of high-risk individuals in the general study population. Patients may also not be cognizant of their complete medical histories, underscoring the need to thoroughly review and document a patient’s medical history. Further, this study only used data accessible from the EMR, and not all outside records or serological information were available in the EMR. This may underestimate screening and vaccination data as many patients seek care at several inpatient and outpatient centers, along with other primary care services. Hence, the true number of unvaccinated individuals may be even lower. However, given the large proportion of underserved individuals in our study population, it is likely that our safety-net hospital (as part of our larger urban academic center) is the primary site for many of these patients’ healthcare. Future studies are needed to further identify and improve ways to improve HBV vaccinations, particularly in high-risk patients.

In conclusion, Despite the most recent CDC guidelines, patients at high-risk for HBV infection are not being adequately screened and vaccinated against hepatitis B infection and show little improvement compared to historical averages, even when compared to other studies. Despite numerous studies and taskforce- or professional society-based guidelines, there has been minimal improvement in vaccination rates over the past several years. We found that comorbid conditions such as older age, and diabetes were associated with a lower likelihood of being screened or vaccinated for HBV, while the opposite was found in patients with ESRD. Vaccination rates were lower in Black and Hispanic populations.

An improvement in HBV vaccination coverage is needed. Educating patients and clinicians alike to help identify highest-risk populations is essential, in order to raise awareness that could potentially increase HBV vaccination rates, with the end goal of decreasing the burden of chronic HBV-related liver disease, including advanced fibrosis, cirrhosis, portal hypertension, and HCC. Public health programs and initiatives are essential at providing these clinical services. Greater vaccination coverage can be achieved by routinely assessing patients’ vaccination status, using standing orders for vaccination, incorporating vaccination information guidelines and prompts in electronic medical records, and using other immunization information systems[26,27].

Identifying patients who are at high-risk and implementation of the CDC HBV vaccination recommendations is important in helping decrease the incidence (and ultimately the prevalence) of HBV infections, along with the physical, emotional, and financial burden of both acute and chronic HBV and its numerous associated sequelae. Educating patients and physicians about hepatitis B vaccination, and implementation of immunization registries, reminder-recall systems and provider prompts may help increase vaccination rates.

Hepatitis B is a liver infection caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV), affecting 1.4 million people in the United States, and 350 people worldwide. HBV infection accounts annually for 4000 to 5500 deaths in the United States and 1 million deaths worldwide from cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Hepatitis B vaccination is 95% effective in preventing infection and the development of chronic disease and liver cancer due to hepatitis B in adults vaccinated before being exposed to the virus. Hepatitis B disproportionately affects certain high-risk populations. HBV vaccination coverage in high-risk individuals in the United States was reported to be around 42% in 2012. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommends all individuals at high-risk for HBV infection undergo vaccination. These guidelines expanded in 2011 to include those with diabetes mellitus (DM). The purpose of our study is to evaluate clinical factors associated with HBV screening and vaccination in high-risk individuals.

Hepatitis B infection is a significant cause of liver disease in the United States. With the advent of HBV vaccination, rates of hepatitis B infection have declined, but the rates of vaccination in high-risk individuals have not significantly increased over previous years. With the recommendation for expanded HBV vaccination guidelines from the CDC, current rates in high-risk individuals may be underestimated. Our research study looks to evaluate clinical factors associated with HBV screening and vaccination in high-risk individuals, which may provide better understanding to the current vaccination rates in this population. Estimating current vaccination rates in high-risk individuals is important for future research that can study different methods to improving vaccination rates.

The main objective of this study was to evaluate screening and vaccination rates in high-risk individuals, and clinical factors associated with screening and vaccination. We found that the vaccination rates in high-risk individuals remains low in our study population, and that these rates are similar to previous national rates despite updated CDC guidelines.

We conducted a retrospective review of 999 patients presenting at a large urban healthcare system from 2012-2017 at high-risk for hepatitis B infection. Patients were considered high-risk for hepatitis B infection based on hepatitis B practice recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control. Medical history including hepatitis B serology, medical diagnoses, demographics, insurance status and social history were extracted from electronic health records. Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify clinical risk factors independently associated with hepatitis B screening and vaccination.

Among the 999 patients, 556 (55.7%) patients were screened for hepatitis B. Of those who were screened, only 242 (43.5%) patients were vaccinated against hepatitis B. Multivariate regression analysis revealed end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [odds ratio (OR): 5.122; 2.766-9.483], alcoholic hepatitis (OR: 3.064; 1.020-9.206), and cirrhosis or end-stage liver disease (OR: 1.909; 1.095-3.329; all P < 0.05) were associated with hepatitis B screening, while increasing age (OR: 0.785; 0.680-0.906), insurance status (0.690; 0.558-0.854), history of DM (OR: 0.518; 0.364-0.737), and human immunodeficiency virus (OR: 0.443; 0.273-0.718; all P < 0.05) were less likely to undergo hepatitis B screening. Of adults vaccinated for hepatitis B, multivariate regression analysis revealed increasing age (OR: 0.755; 0.650-0.878), BMI (0.799; 0.671-0.952), and DM (OR: 0.620; 0.409-0.941; all P < 0.05) were less likely to undergo hepatitis B vaccination.

Vaccination rates in high-risk individuals remain low at 43.5% in our study and ways to improve these rates need to be evaluated. The CDC recommends all individuals at high-risk for HBV infection undergo vaccination. Our study reveals that patients at high-risk for hepatitis B are not being adequately screened and/or vaccinated. With the addition of DM in the CDC HBV vaccination guidelines, we found that older age, diabetes, and decreasing insurance coverage were associated with a lower likelihood of being screened or vaccinated for HBV, while ESRD was associated with increased likelihood of screening. Vaccination rates likely remain low due to lack of knowledge by patients and physicians on appropriate implementation of CDC guidelines. Identifying patients who are at high-risk for infection is an important step in decreasing the incidence (and ultimately the prevalence) of HBV infections in the United States. Future studies are needed to further identify and improve ways to improve HBV vaccinations, particularly in high-risk patients.

Identifying high-risk patients who are likely to benefit from further review of their HBV vaccination status and implementation of vaccination to those in need is of high importance in the prevention of hepatitis B infection and its sequelae including chronic liver disease, cirrhosis and HCC. Despite CDC recommendations, HBV vaccination rates in high-risk individuals are still not optimal. The direction of future research should be aimed at obtaining national rates to better gauge vaccination in the United States. Also, with the knowledge of current vaccinations rates, future studies can evaluate different modalities including patient and physician education, immunization registries, reminder-recall systems and provider prompts that can help improve HBV management.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Ponti FD S- Editor: Cui LJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Tan WW

| 1. | Wörns MA, Teufel A, Kanzler S, Shrestha A, Victor A, Otto G, Lohse AW, Galle PR, Höhler T. Incidence of HAV and HBV infections and vaccination rates in patients with autoimmune liver diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:138-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Proceedings of the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) International Consensus Conference on Hepatitis B. September 14-16, 2002. Geneva, Switzerland. J Hepatol. 2003;39 Suppl 1:S1-235. [PubMed] |

| 3. | El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1118-1127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2881] [Cited by in RCA: 3088] [Article Influence: 220.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | WHO position paper on hepatitis A vaccines: June 2012-recommendations. Vaccine. 2013;31:285-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ott JJ, Irving G, Wiersma ST. Long-term protective effects of hepatitis A vaccines. A systematic review. Vaccine. 2012;31:3-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Goldstein ST, Alter MJ, Williams IT, Moyer LA, Judson FN, Mottram K, Fleenor M, Ryder PL, Margolis HS. Incidence and risk factors for acute hepatitis B in the United States, 1982-1998: implications for vaccination programs. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:713-719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Daniels D, Grytdal S, Wasley A; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Surveillance for acute viral hepatitis - United States, 2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2009;58:1-27. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Mast EE, Weinbaum CM, Fiore AE, Alter MJ, Bell BP, Finelli L, Rodewald LE, Douglas JM, Janssen RS, Ward JW; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Part II: immunization of adults. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1-33; quiz CE1-4. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of hepatitis B vaccination for adults with diabetes mellitus: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1709-1711. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Williams WW, Lu PJ, O'Halloran A, Kim DK, Grohskopf LA, Pilishvili T, Skoff TH, Nelson NP, Harpaz R, Markowitz LE, Rodriguez-Lainz A, Fiebelkorn AP. Surveillance of Vaccination Coverage among Adult Populations - United States, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66:1-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 297] [Cited by in RCA: 312] [Article Influence: 39.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lu PJ, Byrd KK, Murphy TV, Weinbaum C. Hepatitis B vaccination coverage among high-risk adults 18-49 years, U.S., 2009. Vaccine. 2011;29:7049-7057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kim WR. Epidemiology of hepatitis B in the United States. Hepatology. 2009;49:S28-S34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Szmuness W, Stevens CE, Harley EJ, Zang EA, Oleszko WR, William DC, Sadovsky R, Morrison JM, Kellner A. Hepatitis B vaccine: demonstration of efficacy in a controlled clinical trial in a high-risk population in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:833-841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 791] [Cited by in RCA: 677] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis B Questions and Answers for the Public. Available from: URL: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hbv/bfaq.htm. |

| 15. | Jain N, Yusuf H, Wortley PM, Euler GL, Walton S, Stokley S. Factors associated with receiving hepatitis B vaccination among high-risk adults in the United States: an analysis of the National Health Interview Survey, 2000. Fam Med. 2004;36:480-486. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Hope VD, Ncube F, Hickman M, Judd A, Parry JV. Hepatitis B vaccine uptake among injecting drug users in England 1998 to 2004: is the prison vaccination programme driving recent improvements? J Viral Hepat. 2007;14:653-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Denis F, Abitbol V, Aufrère A. Evolution of strategy and coverage rates for hepatitis B vaccination in France, a country with low endemicity. Med Mal Infect. 2004;34:149-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | van Houdt R, Koedijk FD, Bruisten SM, Coul EL, Heijnen ML, Waldhober Q, Veldhuijzen IK, Richardus JH, Schutten M, van Doornum GJ, de Man RA, Hahné SJ, Coutinho RA, Boot HJ. Hepatitis B vaccination targeted at behavioural risk groups in the Netherlands: does it work? Vaccine. 2009;27:3530-3535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Adult vaccination coverage--United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:66-72. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Lau DT, Hewlett AT. Screening for hepatitis A and B antibodies in patients with chronic liver disease. Am J Med. 2005;118 Suppl 10A:28S-33S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Vento S, Garofano T, Renzini C, Cainelli F, Casali F, Ghironzi G, Ferraro T, Concia E. Fulminant hepatitis associated with hepatitis A virus superinfection in patients with chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:286-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 580] [Cited by in RCA: 455] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Keeffe EB. Is hepatitis A more severe in patients with chronic hepatitis B and other chronic liver diseases? Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:201-205. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Lee SD, Chan CY, Yu MI, Lu RH, Chang FY, Lo KJ. Hepatitis B vaccination in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Med Virol. 1999;59:463-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mendenhall C, Roselle GA, Lybecker LA, Marshall LE, Grossman CJ, Myre SA, Weesner RE, Morgan DD. Hepatitis B vaccination. Response of alcoholic with and without liver injury. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:263-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bronowicki JP, Weber-Larivaille F, Gut JP, Doffoël M, Vetter D. [Comparison of immunogenicity of vaccination and serovaccination against hepatitis B virus in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1997;21:848-853. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Progress in immunization information systems--United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:48-51. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Community Preventive Services Task Force. Recommendation for use of immunization information systems to increase vaccination rates. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2015;21:249-252. [PubMed] |