Published online Sep 27, 2018. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v10.i9.585

Peer-review started: March 29, 2018

First decision: April 18, 2018

Revised: April 26, 2018

Accepted: June 8, 2018

Article in press: June 9, 2018

Published online: September 27, 2018

Processing time: 182 Days and 17.4 Hours

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is one of the main public health problems across the globe, since almost one third of the world population presents serological markers of contact with the virus. A profound impact on the epidemiology has been exerted by universal vaccination programmes in many countries, nevertheless the infection is still widespread also in its active form. In the areas of high endemicity (prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen positivity > 7%), mother-to-child transmission represents the main modality of infection spread. That makes the correct management of HBV in pregnancy a matter of utmost importance. Furthermore, the infection in pregnancy needs to be carefully assessed and handled not only with respect to the risk of vertical transmission but also with respect to gravid women health. Each therapeutic or preventive choice deserves to be weighed upon attentively. On many aspects evidence is scarce or controversial. This review will highlight the latest insights into the paramount steps in managing HBV in pregnancy, with particular attention to recommendations from recent guidelines and data from up-do-date research syntheses.

Core tip: Hepatitis B is still a matter of concern worldwide. Particularly challenging is the correct management of infection during pregnancy. Two aspects have to be taken into account: The potential need to treat the mothers and, at once, the necessity to prevent the vertical transmission of the virus to the infants. This review will discuss the most up-to-date evidence on therapeutic and preventive interventions in several scenarios characterizing the course of hepatitis B in pregnancy.

- Citation: Maraolo AE, Gentile I, Buonomo AR, Pinchera B, Borgia G. Current evidence on the management of hepatitis B in pregnancy. World J Hepatol 2018; 10(9): 585-594

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v10/i9/585.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v10.i9.585

Despite the availability of effective preventive measures, particularly active immunization through vaccination[1], hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is still today a major public health issue worldwide. According to the most recent and robust estimates, 3.61% of the global population is chronically infected, as expressed by the prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-positivity[2]. Of course, there is a relevant heterogeneity both across and within continents and states as far as endemicity is concerned: Western Pacific Region and Africa are the world areas with the highest prevalence[2].

Even larger is the number of people having serologic markers of previous contact with HBV: About 2 billion subjects worldwide[3]. These individuals showing markers of resolved/occult HBV disease deserve special attention in case they undergo immunosuppressive treatment[4]. Nevertheless, and not surprisingly, the major disease burden is related to chronic infection. In 2013, HBV was responsible for nearly 686000 deaths globally, a figure that places the virus in the top 20 causes of mortality among humans[5]. Of note, different from other major communicable diseases, the burden of viral hepatitis, mainly driven by HBV and hepatitis C virus (HCV), has increased in terms of morbidity and mortality between 1990 and 2013[6].

Chronic HBV infection may evolve to cirrhosis, a condition characterized by profound alteration of liver architecture and function, in about 20% of subjects and may result in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), as a consequence of cirrhosis itself or of viral pro-oncogenic properties[7]. In turn, cirrhosis may be responsible for a vast array of complications: Infections[8], mainly spontaneous bacterial peritonitis[9] and bloodstream infections[10], ascites[11], hepatorenal syndrome[12], variceal bleeding[13].

Despite the remarkable efforts during the last decades aimed at implementing effective vaccination strategies worldwide[14], 50 million new cases of hepatitis B are still diagnosed each year, most due to mother-to-child transmission (MTCT)[15].

As a matter of fact, the transmission routes differ according to the entity of HBV endemicity: In areas of high prevalence (> 7%), vertical transmission prevails, whereas in low endemic regions (prevalence < 2%), sexual transmission is the major culprit[16]. The way and the timing of transmission are crucial factors influencing the probability of developing chronic HBV infection: Indeed, this likelihood is higher in subjects infected perinatally (up to 90%) when compared with rate of chronicity in adults after the acute phase (< 1%)[17]. Around 15%-40% of individuals suffering from chronic hepatitis develops cirrhosis[18].

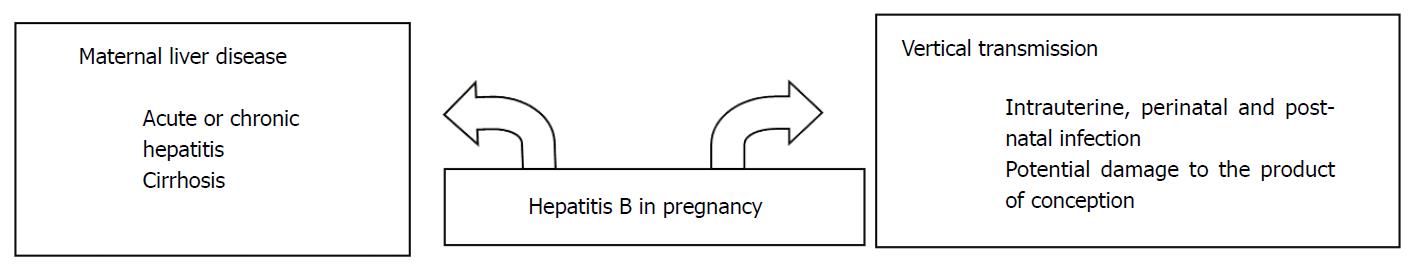

All these figures underpin the necessity of correctly managing pregnant women with HBV infection, in order to reduce the burden of disease. Attention must be paid not only in developing countries, but also in regions such as Australia, United States, and Western Europe, where immigration from areas of high HBV endemicity may represent a challenge for physicians not accustomed to manage HBV infection in particular settings[15]. Of course, HBV infection in pregnancy is not only a problem for infants, but also for women’s health (Figure 1). In this review, the current state of the art regarding the best management of HBV in pregnancy, both for the mother and child, will be discussed.

The relationship between liver diseases and pregnancy is proteiform, and three categories of pathological conditions can be described: The ones representing underlying status, pre-existing to the moment of conception; the ones coincidental with maternity; and eventually, the ones specific of pregnancy (for example, pre-eclampsia)[19]. Viral hepatitis falls into the first two categories[19].

As far as acute hepatitis B is concerned, its occurrence during pregnancy is not associated with higher mortality, and the related clinical picture is not distinguishable from that in the general population[20]. This notion was further confirmed by a case-control study run in China, comparing 22 pregnant patients and 87 matched non-gravid women, all suffering from acute hepatitis B: No difference with regard to mortality and incidence of fulminant hepatitis was detected[21]. Of note, the HBsAg loss and seroconversion rates were lower in the first group, suggesting that pregnancy might act as a risk factor for chronicity[21].

An interesting and recent systematic review has assessed the impact of inactive HBV carriage on gravid women health, showing that this condition is not associated with complications in pregnancy, so this condition does not need any particular therapeutic measure[22]. When it comes to chronic (active) HBV infection already established before conception, the immunological modifications that occur in pregnancy may raise the level of HBV viremia, whereas alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels are normal or just above the upper limit of normal (ULN)[23].

A more relevant exacerbation of chronic hepatitis might happen after delivery in a notable percentage of women (up to 45%), as observed in a small retrospective cohort involving 38 pregnancies in 31 subjects, in which the flare was defined as a three times increase in ALT levels within 6 mo post-partum[24]. Authors suggested that this phenomenon, also found in the subgroup of women (8/13, 62%) who had undergone a course of lamivudine (LAM) during the third trimester, was attributable to the restoration after delivery of the immune system, whose functions were previously altered to prevent foetus rejection[24]. The topic has been further elucidated by a subsequent prospective study recruiting 126 women: Post-partum flares, defined as ALT levels twice the ULN or the baseline, were described in 27 (25%) individuals, usually asymptomatic and with spontaneous resolution[25]. At multivariate analysis, HBeAg positivity turned out to be the most relevant predictor of post-partum flares, although just barely not reaching the statistical significance (P = 0.051)[25]. Another study, a multicentre retrospective cohort involving 101 women and 113 pregnancies, did not identify clear risk factors for exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B after delivery[26].

With regard to maternal complications, chronic HBV infection does not seem a risk factor for many of them, as derived by research syntheses. A meta-analysis collecting data on 9088 placenta previa cases and 15571 placental abruption cases failed to demonstrate an association with HBV, implicated as a driver of an inflammation state able to induce dysfunction of trophoblasts: Odds ratio (OR) equal to 0.98 with 95%CI equal to 0.60-1.62 and OR = 1.42 with 95%CI: 0.93-2.15, respectively[27]. A further meta-analysis involving 439514 subjects showed that HBV was not associated with increased risk of gestational diabetes mellitus (adjusted OR = 1.11, 95%CI: 0.96-1.28), a link suggested by the potential role played by the virus in inducing insulin resistance[28]. Another research synthesis of observational studies did not detect a statistical significance between chronic HBV infection and preterm labour (OR = 1.12, 95%CI: 0.94-1.33)[29]. More recently, a meta-analysis including 11566 women has, quite surprisingly, highlighted a negative association between chronic HBV infection and preeclampsia (OR = 0.77, 95%CI: 0.65-0.90, P = 0.002): Actually, the protective effect, probably due to impaired immune response and/or increased immune-tolerance caused by the virus (preeclampsia is linked with exaggerated activation of immune system), was apparent only in an Asian population, as derived from the subgroup analysis[30].

Another aspect to be considered is how the most advanced stage of chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, impact the health of pregnant women, in the particular setting of HBV infection. Cirrhosis is, fortunately, an infrequent occurrence in pregnancy due to two factors: The development of end-stage liver disease requires time and more often takes place when women have gone beyond their reproductive age; moreover, hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction related to cirrhosis[31] may ensue in anovulation and amenorrhea[32]. However, when present, cirrhosis is a relevant health issue for pregnant women. In a large population-based retrospective study in the United States on gravid women, comparing 339 cirrhotic cases with 6625 matched-controls, maternal mortality and complications of pregnancy (e.g., uterovaginal haemorrhage, pre-eclampsia, peri-partum infections) were higher among individuals suffering from liver disease: For example, the maternal death rate was 1.8% vs 0% (P < 0.0001)[33]. Mortality among cirrhotic pregnant women was higher in cases of viral aetiology (HBV as well as HCV)[34]. The high burden of liver cirrhosis in pregnancy has been confirmed in a more recent prospective study, matching 176 cirrhotic gravid women with 2179 pregnant non-cirrhotic women and 1034 cirrhotic but not pregnant female subjects[34]. Maternal mortality rate was superior in the study group (7.8%) than in the first (0.2%) and second control group (2.5%; P = 0.001); variceal haemorrhage during vaginal delivery was the most frequent reason of maternal death[34]. Indeed, the rupture of oesophageal varices represents probably the most important complications among the ones directly related to cirrhosis in pregnant women, especially in the advanced phase of pregnancy or during labour[35]. An important predictor of liver-related complications during pregnancy is a model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score ≥ 10[36].

The paramount issue is which pregnant women with HBV infection should be treated[37].

In the case of acute hepatitis B, the main goal of the treatment should be the prevention of acute liver failure[38]. The quality of current evidence regarding pharmacological interventions in this setting is unfortunately very low[39]. Nevertheless, antiviral therapy is rarely necessary, since the large majority of adult patients (> 95%) have a full and spontaneous recovery[38], and, as mentioned above, the clinical course of this entity does not differ between pregnant and non-pregnant women. The problem is the management of cases suffering from severe acute HBV infection[40]. First, in case of serious hepatitis affecting gravid women, differential diagnosis is essential to rule out, for example, diseases unique to pregnancy, such as acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP) as well as haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets (HELLP) syndrome, representing two hepatic emergencies in the third trimester[40]. Once the viral aetiology is established, borrowing the recommendations applying to the general population, the treatment should rely on nucleos(t)ide analogue (NA) agents and the patients should be considered, as extrema ratio, for liver transplantation[38]. Therapy with NAs can prevent acute liver failure and the related mortality[38], but needs to be started early in the course of severe acute hepatitis, otherwise the protective effect does not display[41]. Due to the lack of high-quality data[39], there is high uncertainty regarding the best therapeutic options; recommendations for the general population support the use of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), entecavir (ETV), and lamivudine (LAM)[38]. To date, there is no information about the use in severe acute hepatitis B of tenofovir alafenamide (TAF), the prodrug of tenofovir developed to ameliorate the safety and tolerability profile of TDF[42]. Among the above-mentioned NAs, LAM and TDF are preferable in pregnancy, in particular the latter one, owing to its high resistance barrier that is fundamental in case of prolongation of therapy for chronicity[43]. In extreme circumstances, liver transplantation might be a therapeutic option even during pregnancy if hepatic decompensation exceeds the point of no return: The difficulty of the task is doubled, as it involves two organisms (the mother and the foetus), but successful cases have been described, also related to fulminant hepatitis B[44].

At any rate, the management of severe acute hepatitis B in pregnancy needs more robust data to draw firm conclusions. Today, a case-by-case approach is needed. Chronic HBV infection is surely a more common scenario in pregnancy than fulminant hepatitis B. In the general population, according to the most authoritative guidelines endorsed by societies from all over the world, the main criteria for treatment are based on serum HBV DNA levels, serum ALT levels, and severity of liver disease[38,45,46]. Despite some discrepancies (for example, the locution “inactive carriers”, discouraged by Asian and European guidelines but kept in the American ones), there is a substantial consensus upon the following items, concerning situations wherein antiviral therapy is recommended: Cirrhosis; absence of cirrhosis, but viraemia > 20000 International Units (IU)/mL and ALT levels > 2 × ULN; no cirrhosis, viraemia > 2000 IU/mL, ALT 1-2 × ULN but at least moderate to severe inflammation on liver biopsy[38,45,46]. In the general population, there are two therapeutic options: Interferon-alfa (IFNα) and NAs[16]. The rationale underpinning the choice of one strategy over another one is different. IFNα is administered to provide long-term immunological control through a finite duration treatment, attempting to achieve the so-called “functional cure” by HBsAg loss, but it is burdened by several side effects. NAs have a definitely better safety and tolerability profile, provide a very good virological control (persistent inhibition of HBV replication), but the duration of therapy is indefinite[47].

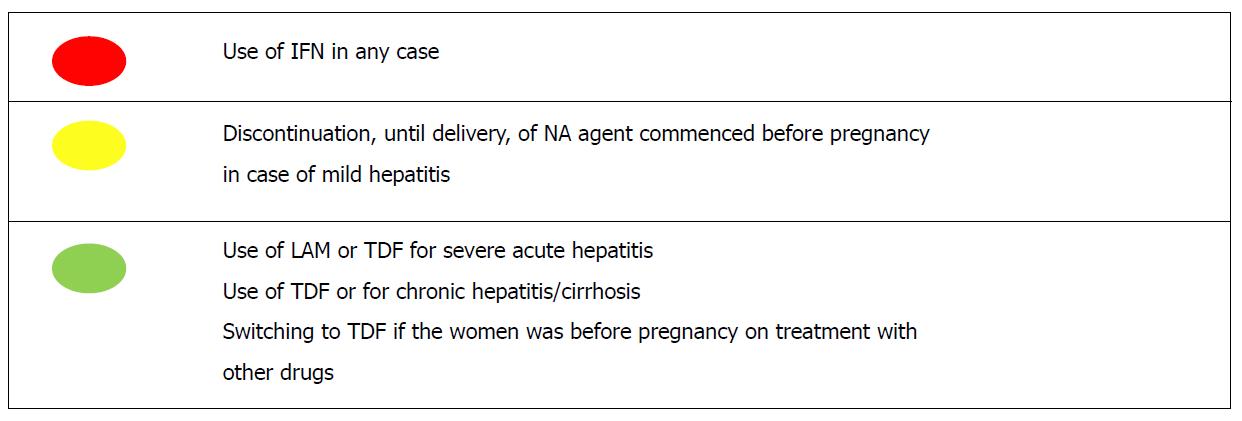

At any rate, in pregnant women, IFNα is contraindicated; therefore the therapeutic armamentarium is limited to NAs[48]. Among this category, currently TDF (alternatively TAF) and ETV are considered the first-line drugs when starting a new therapy for chronic HBV infection, combining an excellent safety profile with a genetic barrier of resistance higher than earlier available agents, such as LAM and telbivudine (LdT)[38,45]. Nevertheless, according to the 5-class labelling used by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) until 2015 as for safety in pregnancy, ETV has been classified as a “category C” agent, differently from LdT and TDF, labelled as “category B” drugs: That means the absence of teratogenic effects in animal studies[49]. As a matter of fact, TDF is the drug of choice for pregnant females with chronic HBV infection requiring antiviral therapy (i.e., advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis), also in light of the huge amount of data from the setting of gravid women under treatment against the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), in which TDF is administered safely in combination with other antiretroviral agents throughout the pregnancy, since the first trimester[50].

A delicate issue is how to handle cases of women who become pregnant when already on anti-HBV treatment[51]. As a rule, appropriateness of therapy should be re-evaluated, striking a balance between benefits for the mother and the safety of the foetus[50]. Whatever the diseases severity, IFNα must be immediately stopped; therapy with a NA can be continued in case of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis, switching to TDF if therapy was started before conception with another drug (for instance, ETV)[51]. In case of mild disease (e.g., no advanced fibrosis, normal ALT levels, viraemia between 2000 UI/mL and 20000 IU/mL), discontinuation of therapy until delivery might be a viable option, as long as an adequate monitoring is carried out to re-start immediately treatment if necessary[51]. Eventually, another matter of concern is the management of HBV resistance cases: In pregnant women there is limited experience, nonetheless, in gravid subjects experiencing treatment failure (HBV DNA rebound) under LAM or LdT, switching to TDF appears a safe and effective option[52]. In Figure 2 the current knowledge regarding the treatment of HBV infection in pregnant women is summarized.

Besides the “long-term” risks of HBV MTCT, such as chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and HCC[53], physicians caring for pregnant women with HBV infection have to take into account the “short-term” potential consequences for the product of conception: For example, small for gestational age (SGA), foetal distress, preterm birth (PTB), low birth weight (LBW), congenital anomalies, and neonatal jaundice[54].

PTB, defined as a birth occurring earlier than 37 completed weeks of gestation, represents one of the most feared complications, being worldwide the main cause of death in children under 5 years of age[55]. A very large population-based cohort study run in China, involving 489965 women who had singleton livebirths (of whom 20827, the 4.3%, with HBV infection diagnosed before pregnancy), showed that, adjusting for several covariates, in comparison with gravid subjects without HBV infection, HBsAg positive and HBeAg negative pregnant women had a 26% higher risk of PTB, whereas in women who were both HBsAg and HBeAg positive this percentage was equal to 20%[56]. Higher risks were observed also for early PTB (before 34 wk of gestation); unfortunately, data on viral load were not available. At any rate, the results of this recent study advocates proper medical intervention against HBV in pregnancy to improve neonatal outcomes[56].

Another large population-based study (sample size over 2000000 people), conducted in the United States and focused on neurological complications at birth, demonstrated that women with HBV, compared with gravid subjects without HBV, had a higher likelihood to generate infants who suffered from brachial plexus injury, even after adjusting for several confounders (OR = 2.04, 95%CI: 1.15-3.60)[57]. In a prospective cohort study in China, investigating 21004 pregnant women, of which were 513 HBV-positive and 20491 HBV-negative, no differences between the two groups were detected with regard to the rate of stillbirth, SGA and LBW, but the proportion of miscarriage was higher among gravid subjects with HBV (adjusted OR = 1.71, 95%CI: 1.23-2.38), but also in this study data on viraemia were lacking[58].

The viral load is just the key factor to determine the risk of HBV MTCT[59], that, in absence of any preventive measure, ranges from 10% to 40% when mothers are HBeAg-negative and from 70% to 90% in HBeAg-positive mothers[60], much higher rates in comparison with the other hepatotropic virus, HCV (0%-30%)[61].

The modalities of vertical transmission are: Intrauterine, peripartum and post-natal infection[59]. The transmission in utero is the most insidious route, since it is represents the most important cause of passive-active immunoprophylaxis failure[62]. There is no consensus to define correctly this occurrence (many criteria have been proposed, such as, among the many, persistent serum anti-HBc IgM positive after birth or Pre-S1 protein positivity in umbilical blood); supposed mechanisms are the passage of serum/body fluid through damaged placenta, the transmission of infected germ cells and the transfer of infected placenta or peripheral blood mononuclear cells[62]. HBeAg-positivity is a notable driver of intrauterine transmission: The antigen can cross the placenta barrier through leakages or through infected cells, and it is linked with higher levels of HBV replication[35]. Natal transmission during delivery represents the most impactful modality, being offspring exposed to blood or other maternal body fluids while passing the genital tract[62]. Finally, there is postnatal infection, which encompasses all the cases in which the transmission occurs after delivery, because of contacts with maternal fluids such breast milk or blood[62].

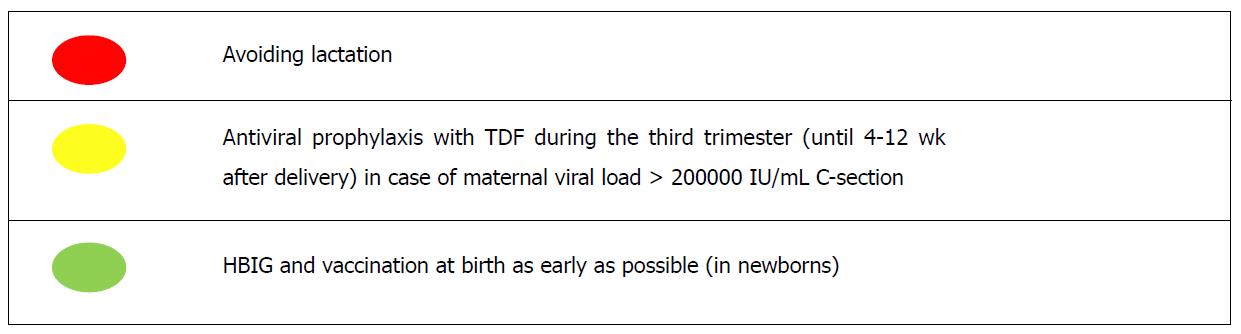

All guidelines, in line with the recommendations of the World Health Organization, support the administration, within 12 h of birth, of active (first dose of anti-HBV vaccine) and passive immunization through hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) to the offspring born to HBsAg-positive mothers, a measure able to abate the rate of HBV MTC to > 90% to < 10%[38,45,46] and supported by high-quality evidence[63]. The paramount issue is how to avoid the failure of passive-active immunoprophylaxis, mainly ascribable to intrauterine transmission[64]. The most recent international guidelines recommend, for gravid women not already on NAs treatment, the use of antiviral prophylaxis from week 24-28 of gestation (third trimester) if viral load > 200000 IU/mL and/or serum HBsAg levels > 4 log10 IU/mL[38,45]. The viraemia threshold was first set based on a retrospective study involving 869 mother-newborns pairs who had received proper immunoprophylaxis: Failures occurred only in infants born to HBeAg-positive women with viral load > 200000 IU/mL (maternal viraemia levels, along with detectable HBV DNA in the cord blood, was the main risk factor at multivariate analysis)[65]. Subsequently, serum HBsAg levels emerged as a surrogate marker for viral load as well as predictive variable of HBV MTCT[66,67].

The benefit of antiviral prophylaxis as an additional measure to HBIG and vaccination was clear in a meta-analysis of 26 studies involving 3622 pregnant women, with a risk ratio equal to 0.3; the use of LdT, LAM, and TDF turned out to be safe[68]. There is no randomized controlled trial (RCT) directly comparing NAs as for HBV MTCT prevention: A Bayesian network meta-analysis (NMA) in 2016 demonstrated greater efficacy of LdT over LAM, but TDF was not taken into account[69]. A more recent NMA failed to demonstrate a superiority of TDF vs LAM[70]. At any rate, TDF is the favourite choice because of its superior barrier to resistance[38,45]. Indeed, TDF was the drug of choice for a non-randomized trial and two RTCs vs placebo published during the last 3 years[71-73]. The first two studies demonstrated that TDF (administered throughout the last trimester of pregnancy until 1 mo post-partum) decreased significantly the rate of HBV vertical transmission in comparison with placebo in women HBeAg-positive having high viral load[71,72]. On the contrary, the last and more recent RCT, not considered by guidelines due to publishing timing reasons, failed to detect a significant difference between the TDF group and the placebo arm (no events out of 147 newborns vs three infection out of 147 infants, respectively, P = 0.29)[73]. The study protocol contemplated the administration of TDF or placebo from 28 wk of gestation to 2 mo post-delivery in HBeAg-positive women, the large majority of them having viraemia > 20000 UI/mL, and its sample size was as large as the ones of the previous studies taken altogether[73]. Therefore, the results of this negative trial brings into question the usefulness of NAs, specifically TDF, as additional preventive measure during the last period of pregnancy and will need to be considered and put in the right perspective by the next research syntheses and guidelines. One of the possible explanation is the very early administration of HBV vaccination (the median time was just 1.2 h after birth)[74].

Pending new compelling evidence, the combination of HBIG and vaccine at birth is the mainstay of HBV MTCT prevention in newborns; antiviral prophylaxis in late pregnancy may be considered for HBeAg-positive gravid women with high viral load[75]. Furthermore, the absence of harm, weighing risks and benefits, might tip the scale in favour of NAs administration during the last trimester. The alarm raised by a case-control study (74 TDF-exposed and 69 TDF-unexposed infants) about the risk of lower neonatal bone mineral content (difference equal to 12% at 1 mo of birth) because of TDF during late pregnancy[76] has been refuted by subsequent work (conducted by the same study group) on 509 children: At 2 years of age TDF was not linked with lower length or head circumference[77]. This is in accordance with evidence from research synthesis confirming the safety, both for mothers and their offspring, of TDF use in pregnancy[78]. If administered, there is no consensus about when to stop prophylaxis. Some guidelines support its prolongation until 12 wk after delivery[38], others until 4 wk post-partum[45]: The protocol of main trials about TDF provided for the use of drug for 4[71,72] or 8[73] wk after delivery. The point is to strike a balance between the potential risk of interfering with breastfeeding and the benefit on possible post-partum hepatitis flares[35]. More conservative recommendations[45] rely on a prospective study recruiting 91 women (101 pregnancies), showing no advantages in terms of hepatitis flare rate for gravid subjects who extended antiviral prophylaxis with TDF beyond 4 wk after delivery[79]. Nevertheless, prolongation of antiviral prophylaxis[38] might be useful at least for women with elevated ALT during pregnancy, since they present a higher risk of post-partum hepatitis flare, as showed by a Chinese study wherein mothers were administered LdT[80]. With regard to other preventive strategies, unfortunately there is high uncertainty, also due to very low available evidence, upon the potential benefits of the antenatal administration of HBIG, to exploit the maternofoetal diffusion through the placenta, which reaches its peak during the third trimester[81].

The last issues involve the following topics: Delivery modalities, invasive procedures during pregnancy and breastfeeding[38,45]. There is a huge debate about the efficacy of caesarean section (C-section) as a preventive measure. Guidelines do not back its elective implementation[45], although meta-analyses reveal that C-section, compared with vaginal delivery, significantly decrease the risk of HBV vertical transmission[82,83]. The problem is the high heterogeneity of the studies whose results have been retrieved and analysed by these research syntheses, one collecting data from 10 studies[82], and the most recent from only Chinese datasets[83]: These relevant limitations advocate well designed studies to be performed in order to shed light on this matter.

Unfortunately, there is scarce evidence regarding the best practice when invasive procedures are carried out. As far as amniocentesis is concerned, a quite recent matched case-control study (63 infants whose HBsAg-positive mothers had underwent the procedure and 198 newborns whose HBsAg-positive mothers had not underwent amniocentesis) found that HBV MTCT was more frequent among cases (6.35% vs 2.53%; P = 0.226); notably, the difference was apparent when maternal viral load was taken into account, especially above the threshold of 200000 IU/mL (50% vs 4.5%, P = 0.006)[84]. Neither cases nor controls were born to mothers who were administered antiviral prophylaxis during pregnancy[84]. No strong recommendations can be drawn on this basis; therefore, while waiting for studies that will investigate the potential role of antiviral prophylaxis in women with high viraemia undergoing amniocentesis, guidelines suggest that a careful assessment of harms and benefits of the invasive procedure is necessary[45].

The last topic is breastfeeding. On one hand, lactating is allowed as long as the standard measures of passive/active prophylaxis are taken[38,45,46]. On the other hand, there are some concerns about the safety of NAs, particularly TDF, during breastfeeding[38,45,46]. Experiences in the HIV field indicate that antivirals are well tolerated[85] and in particular TDF appears to be safe as to infant outcomes[86]. In Figure 3, a summary of the current knowledge regarding the HBV MTCT prevention is depicted.

When facing HBV in pregnancy, there are two different problems to address: The first is represented by the maternal liver disease, the second by the risk of MTCT. The two issues are actually strictly inter-connected, but choices regarding potential antiviral use can profoundly differ, especially as for timing. Unfortunately, to date many questions present answers backed up by low-quality evidence, a not rare occurrence when pregnancy is involved. For instance, it is not simple to set up large and multicentre RCTs in this setting. Moreover, there is a constant need to take carefully into account benefits and harms of each intervention, potentially impacting not only one but two lives. Regarding the first issue, in essence the indications for treatment of general population also apply to pregnant women. The drug of choice is represented by TDF; in case the gravid subjects are already on treatment with another NA, a switch is advised. IFN is absolutely contraindicated.

As to the second issue, the only mandatory measure, underpinned by incontrovertible evidence, is represented by providing passive and active immunoprophylaxis to the newborns, starting the schedule as early as possible at birth. The use of antivirals as a preventive weapon, for women not falling in the categories that require treatment, is recommended during the last trimester (until 4-12 wk after delivery) just in case of high viraemia (> 200000 UI/mL), but evidence collected so far is not solid. The drug of choice also in this case is TDF, although there is no direct or indirect proof of superiority over other NAs allowed in pregnancy; nevertheless, among them it shows the highest barrier to resistance. To date there are no data regarding the use of TAF in pregnancy, which could represent an important option, combining the same efficacy with a better safety profile.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Dogan UB, Farshadpour F, Tu H S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Tan WW

| 1. | Orlando R, Foggia M, Maraolo AE, Mascolo S, Palmiero G, Tambaro O, Tosone G. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection: from the past to the future. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34:1059-1070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Schweitzer A, Horn J, Mikolajczyk RT, Krause G, Ott JJ. Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013. Lancet. 2015;386:1546-1555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1806] [Cited by in RCA: 1998] [Article Influence: 199.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 3. | Kwak MS, Kim YJ. Occult hepatitis B virus infection. World J Hepatol. 2014;6:860-869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bessone F, Dirchwolf M. Management of hepatitis B reactivation in immunosuppressed patients: An update on current recommendations. World J Hepatol. 2016;8:385-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;385:117-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5495] [Cited by in RCA: 5239] [Article Influence: 523.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Stanaway JD, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Fitzmaurice C, Vos T, Abubakar I, Abu-Raddad LJ, Assadi R, Bhala N, Cowie B. The global burden of viral hepatitis from 1990 to 2013: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2016;388:1081-1088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1042] [Cited by in RCA: 988] [Article Influence: 109.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ganem D, Prince AM. Hepatitis B virus infection--natural history and clinical consequences. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1118-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1700] [Cited by in RCA: 1712] [Article Influence: 81.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gentile I, Buonomo AR, Scotto R, Zappulo E, Borgia G. Infections worsen prognosis of patients with cirrhosis irrespective of the liver disease stage. Eur J Intern Med. 2017;46:e45-e47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fiore M, Maraolo AE, Gentile I, Borgia G, Leone S, Sansone P, Passavanti MB, Aurilio C, Pace MC. Nosocomial spontaneous bacterial peritonitis antibiotic treatment in the era of multi-drug resistance pathogens: A systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:4654-4660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Bartoletti M, Giannella M, Lewis R, Caraceni P, Tedeschi S, Paul M, Schramm C, Bruns T, Merli M, Cobos-Trigueros N. A prospective multicentre study of the epidemiology and outcomes of bloodstream infection in cirrhotic patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24:546.e1-546.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Moore KP, Aithal GP. Guidelines on the management of ascites in cirrhosis. Gut. 2006;55 Suppl 6:vi1-v12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Acevedo JG, Cramp ME. Hepatorenal syndrome: Update on diagnosis and therapy. World J Hepatol. 2017;9:293-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 13. | Gentile I, Viola C, Graf M, Liuzzi R, Quarto M, Cerini R, Piazza M, Borgia G. A simple noninvasive score predicts gastroesophageal varices in patients with chronic viral hepatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:81-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Meireles LC, Marinho RT, Van Damme P. Three decades of hepatitis B control with vaccination. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:2127-2132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 15. | Patton H, Tran TT. Management of hepatitis B during pregnancy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:402-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Trépo C, Chan HL, Lok A. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2014;384:2053-2063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1004] [Cited by in RCA: 1157] [Article Influence: 105.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fattovich G, Bortolotti F, Donato F. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B: special emphasis on disease progression and prognostic factors. J Hepatol. 2008;48:335-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 909] [Cited by in RCA: 967] [Article Influence: 56.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Maddrey WC. Hepatitis B: an important public health issue. J Med Virol. 2000;61:362-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hay JE. Liver disease in pregnancy. Hepatology. 2008;47:1067-1076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Jonas MM. Hepatitis B and pregnancy: an underestimated issue. Liver Int. 2009;29 Suppl 1:133-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Han YT, Sun C, Liu CX, Xie SS, Xiao D, Liu L, Yu JH, Li WW, Li Q. Clinical features and outcome of acute hepatitis B in pregnancy. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Keramat A, Younesian M, Gholami Fesharaki M, Hasani M, Mirzaei S, Ebrahimi E, Alavian SM, Mohammadi F. Inactive Hepatitis B Carrier and Pregnancy Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Iran J Public Health. 2017;46:468-474. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Italian Association for the Study of the Liver (AISF); Italian Association for the Study of the Liver AISF. AISF position paper on liver disease and pregnancy. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48:120-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | ter Borg MJ, Leemans WF, de Man RA, Janssen HL. Exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B infection after delivery. J Viral Hepat. 2008;15:37-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Giles M, Visvanathan K, Lewin S, Bowden S, Locarnini S, Spelman T, Sasadeusz J. Clinical and virological predictors of hepatic flares in pregnant women with chronic hepatitis B. Gut. 2015;64:1810-1815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chang CY, Aziz N, Poongkunran M, Javaid A, Trinh HN, Lau D, Nguyen MH. Serum Alanine Aminotransferase and Hepatitis B DNA Flares in Pregnant and Postpartum Women with Chronic Hepatitis B. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1410-1415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Huang QT, Chen JH, Zhong M, Xu YY, Cai CX, Wei SS, Hang LL, Liu Q, Yu YH. The risk of placental abruption and placenta previa in pregnant women with chronic hepatitis B viral infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Placenta. 2014;35:539-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kong D, Liu H, Wei S, Wang Y, Hu A, Han W, Zhao N, Lu Y, Zheng Y. A meta-analysis of the association between gestational diabetes mellitus and chronic hepatitis B infection during pregnancy. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Huang QT, Wei SS, Zhong M, Hang LL, Xu YY, Cai GX, Liu Q, Yu YH. Chronic hepatitis B infection and risk of preterm labor: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Clin Virol. 2014;61:3-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Huang QT, Chen JH, Zhong M, Hang LL, Wei SS, Yu YH. Chronic Hepatitis B Infection is Associated with Decreased Risk of Preeclampsia: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;38:1860-1868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Fede G, Spadaro L, Privitera G, Tomaselli T, Bouloux PM, Purrello F, Burroughs AK. Hypothalamus-pituitary dysfunction is common in patients with stable cirrhosis and abnormal low dose synacthen test. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:1047-1051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Russell MA, Craigo SD. Cirrhosis and portal hypertension in pregnancy. Semin Perinatol. 1998;22:156-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Shaheen AA, Myers RP. The outcomes of pregnancy in patients with cirrhosis: a population-based study. Liver Int. 2010;30:275-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Rasheed SM, Abdel Monem AM, Abd Ellah AH, Abdel Fattah MS. Prognosis and determinants of pregnancy outcome among patients with post-hepatitis liver cirrhosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;121:247-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Borgia G, Carleo MA, Gaeta GB, Gentile I. Hepatitis B in pregnancy. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4677-4683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 36. | Westbrook RH, Yeoman AD, O’Grady JG, Harrison PM, Devlin J, Heneghan MA. Model for end-stage liver disease score predicts outcome in cirrhotic patients during pregnancy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:694-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | He T, Jia J. Chronic HBV: which pregnant women should be treated? Liver Int. 2016;36 Suppl 1:105-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2017;67:370-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3745] [Cited by in RCA: 3800] [Article Influence: 475.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 39. | Mantzoukis K, Rodríguez-Perálvarez M, Buzzetti E, Thorburn D, Davidson BR, Tsochatzis E, Gurusamy KS. Pharmacological interventions for acute hepatitis B infection: an attempted network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;3:CD011645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practical Guidelines on the management of acute (fulminant) liver failure. J Hepatol. 2017;66:1047-1081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 417] [Cited by in RCA: 621] [Article Influence: 77.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 41. | Wang CY, Zhao P, Liu WW; Acute Liver Failure Study Team. Acute liver failure caused by severe acute hepatitis B: a case series from a multi-center investigation. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2014;13:23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Scott LJ, Chan HLY. Tenofovir Alafenamide: A Review in Chronic Hepatitis B. Drugs. 2017;77:1017-1028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Tavakolpour S, Darvishi M, Mirsafaei HS, Ghasemiadl M. Nucleoside/nucleotide analogues in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B infection during pregnancy: a systematic review. Infect Dis (Lond). 2018;50:95-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Kimmich N, Dutkowski P, Krähenmann F, Müllhaupt B, Zimmermann R, Ochsenbein-Kölble N. Liver Transplantation during Pregnancy for Acute Liver Failure due to HBV Infection: A Case Report. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:356560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Terrault NA, Lok ASF, McMahon BJ, Chang KM, Hwang JP, Jonas MM, Brown RS Jr, Bzowej NH, Wong JB. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology. 2018;67:1560-1599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2290] [Cited by in RCA: 2843] [Article Influence: 406.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Sarin SK, Kumar M, Lau GK, Abbas Z, Chan HL, Chen CJ, Chen DS, Chen HL, Chen PJ, Chien RN. Asian-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B: a 2015 update. Hepatol Int. 2016;10:1-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1985] [Cited by in RCA: 1959] [Article Influence: 217.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Sundaram V, Kowdley K. Management of chronic hepatitis B infection. BMJ. 2015;351:h4263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Vlachogiannakos J, Papatheodoridis GV. Hepatitis B: Who and when to treat? Liver Int. 2018;38 Suppl 1:71-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Pan CQ, Lee HM. Antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis B in pregnancy. Semin Liver Dis. 2013;33:138-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Visvanathan K, Dusheiko G, Giles M, Wong ML, Phung N, Walker S, Le S, Lim SG, Gane E, Ngu M. Managing HBV in pregnancy. Prevention, prophylaxis, treatment and follow-up: position paper produced by Australian, UK and New Zealand key opinion leaders. Gut. 2016;65:340-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Zhou K, Terrault N. Management of hepatitis B in special populations. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;31:311-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Hu YH, Liu M, Yi W, Cao YJ, Cai HD. Tenofovir rescue therapy in pregnant females with chronic hepatitis B. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:2504-2509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Gentile I, Borgia G. Vertical transmission of hepatitis B virus: challenges and solutions. Int J Womens Health. 2014;6:605-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Connell LE, Salihu HM, Salemi JL, August EM, Weldeselasse H, Mbah AK. Maternal hepatitis B and hepatitis C carrier status and perinatal outcomes. Liver Int. 2011;31:1163-1170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, Perin J, Rudan I, Lawn JE, Cousens S, Mathers C, Black RE. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000-13, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet. 2015;385:430-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1928] [Cited by in RCA: 2072] [Article Influence: 207.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Liu J, Zhang S, Liu M, Wang Q, Shen H, Zhang Y. Maternal pre-pregnancy infection with hepatitis B virus and the risk of preterm birth: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5:e624-e632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Salemi JL, Whiteman VE, August EM, Chandler K, Mbah AK, Salihu HM. Maternal hepatitis B and hepatitis C infection and neonatal neurological outcomes. J Viral Hepat. 2014;21:e144-e153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Cui AM, Cheng XY, Shao JG, Li HB, Wang XL, Shen Y, Mao LJ, Zhang S, Liu HY, Zhang L. Maternal hepatitis B virus carrier status and pregnancy outcomes: a prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Chen HL, Wen WH, Chang MH. Management of Pregnant Women and Children: Focusing on Preventing Mother-to-Infant Transmission. J Infect Dis. 2017;216:S785-S791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Gentile I, Zappulo E, Buonomo AR, Borgia G. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2014;12:775-782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Tosone G, Maraolo AE, Mascolo S, Palmiero G, Tambaro O, Orlando R. Vertical hepatitis C virus transmission: Main questions and answers. World J Hepatol. 2014;6:538-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 62. | Yi P, Chen R, Huang Y, Zhou RR, Fan XG. Management of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus: Propositions and challenges. J Clin Virol. 2016;77:32-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Lee C, Gong Y, Brok J, Boxall EH, Gluud C. Effect of hepatitis B immunisation in newborn infants of mothers positive for hepatitis B surface antigen: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2006;332:328-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 283] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Borgia G, Maraolo AE, Gentile I. Hepatitis B mother-to-child transmission and infants immunization: we have not come to the end of the story yet. Infect Dis (Lond). 2017;49:584-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Zou H, Chen Y, Duan Z, Zhang H, Pan C. Virologic factors associated with failure to passive-active immunoprophylaxis in infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers. J Viral Hepat. 2012;19:e18-e25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 284] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Sun KX, Li J, Zhu FC, Liu JX, Li RC, Zhai XJ, Li YP, Chang ZJ, Nie JJ, Zhuang H. A predictive value of quantitative HBsAg for serum HBV DNA level among HBeAg-positive pregnant women. Vaccine. 2012;30:5335-5340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Wen WH, Huang CW, Chie WC, Yeung CY, Zhao LL, Lin WT, Wu JF, Ni YH, Hsu HY, Chang MH. Quantitative maternal hepatitis B surface antigen predicts maternally transmitted hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2016;64:1451-1461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Brown RS Jr, McMahon BJ, Lok AS, Wong JB, Ahmed AT, Mouchli MA, Wang Z, Prokop LJ, Murad MH, Mohammed K. Antiviral therapy in chronic hepatitis B viral infection during pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2016;63:319-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 256] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 26.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Njei B, Gupta N, Ewelukwa O, Ditah I, Foma M, Lim JK. Comparative efficacy of antiviral therapy in preventing vertical transmission of hepatitis B: a network meta-analysis. Liver Int. 2016;36:634-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Siemieniuk RA, Foroutan F, Mirza R, Mah Ming J, Alexander PE, Agarwal A, Lesi O, Merglen A, Chang Y, Zhang Y. Antiretroviral therapy for pregnant women living with HIV or hepatitis B: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e019022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Chen HL, Lee CN, Chang CH, Ni YH, Shyu MK, Chen SM, Hu JJ, Lin HH, Zhao LL, Mu SC, Lai MW, Lee CL, Lin HM, Tsai MS, Hsu JJ, Chen DS, Chan KA, Chang MH; Taiwan Study Group for the Prevention of Mother-to-Infant Transmission of HBV (PreMIT Study); Taiwan Study Group for the Prevention of Mother-to-Infant Transmission of HBV PreMIT Study. Efficacy of maternal tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in interrupting mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis B virus. Hepatology. 2015;62:375-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Pan CQ, Duan Z, Dai E, Zhang S, Han G, Wang Y, Zhang H, Zou H, Zhu B, Zhao W. Tenofovir to Prevent Hepatitis B Transmission in Mothers with High Viral Load. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2324-2334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 471] [Cited by in RCA: 437] [Article Influence: 48.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Jourdain G, Ngo-Giang-Huong N, Harrison L, Decker L, Khamduang W, Tierney C, Salvadori N, Cressey TR, Sirirungsi W, Achalapong J. Tenofovir versus Placebo to Prevent Perinatal Transmission of Hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:911-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Dusheiko G. A Shift in Thinking to Reduce Mother-to-Infant Transmission of Hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:952-953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Chen ZX, Zhuang X, Zhu XH, Hao YL, Gu GF, Cai MZ, Qin G. Comparative Effectiveness of Prophylactic Strategies for Perinatal Transmission of Hepatitis B Virus: A Network Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofx225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Siberry GK, Jacobson DL, Kalkwarf HJ, Wu JW, DiMeglio LA, Yogev R, Knapp KM, Wheeler JJ, Butler L, Hazra R. Lower Newborn Bone Mineral Content Associated With Maternal Use of Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate During Pregnancy. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:996-1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Jacobson DL, Patel K, Williams PL, Geffner ME, Siberry GK, DiMeglio LA, Crain MJ, Mirza A, Chen JS, McFarland E. Growth at 2 Years of Age in HIV-exposed Uninfected Children in the United States by Trimester of Maternal Antiretroviral Initiation. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36:189-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Nachega JB, Uthman OA, Mofenson LM, Anderson JR, Kanters S, Renaud F, Ford N, Essajee S, Doherty MC, Mills EJ. Safety of Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate-Based Antiretroviral Therapy Regimens in Pregnancy for HIV-Infected Women and Their Infants: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;76:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Nguyen V, Tan PK, Greenup AJ, Glass A, Davison S, Samarasinghe D, Holdaway S, Strasser SI, Chatterjee U, Jackson K. Anti-viral therapy for prevention of perinatal HBV transmission: extending therapy beyond birth does not protect against post-partum flare. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:1225-1234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Liu J, Wang J, Jin D, Qi C, Yan T, Cao F, Jin L, Tian Z, Guo D, Yuan N. Hepatic flare after telbivudine withdrawal and efficacy of postpartum antiviral therapy for pregnancies with chronic hepatitis B virus. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:177-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Eke AC, Eleje GU, Eke UA, Xia Y, Liu J. Hepatitis B immunoglobulin during pregnancy for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2:CD008545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Chang MS, Gavini S, Andrade PC, McNabb-Baltar J. Caesarean section to prevent transmission of hepatitis B: a meta-analysis. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28:439-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Yang M, Qin Q, Fang Q, Jiang L, Nie S. Cesarean section to prevent mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus in China: A meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Yi W, Pan CQ, Hao J, Hu Y, Liu M, Li L, Liang D. Risk of vertical transmission of hepatitis B after amniocentesis in HBs antigen-positive mothers. J Hepatol. 2014;60:523-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | White AB, Mirjahangir JF, Horvath H, Anglemyer A, Read JS. Antiretroviral interventions for preventing breast milk transmission of HIV. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;10:CD011323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Mugwanya KK, John-Stewart G, Baeten J. Safety of oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate-based HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis use in lactating HIV-uninfected women. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2017;16:867-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |