修回日期: 2016-06-03

接受日期: 2016-06-21

在线出版日期: 2016-12-18

随着年龄增长, 人体分泌的雌激素的量会逐渐降低. 人体雌激素水平不足, 可引发心血管、骨质疏松以及更年期综合征等多种疾病. 事实上, 植物体内也广泛分布着雌激素成分. 由于植物中的天然雌激素含量较低, 选择含有天然雌激素的膳食不仅可使体内雌激素得到源源不断的微量补充, 同时又不会给机体健康带来影响或损伤. 摄入机体的膳食中的植物雌激素还可被肠道菌群转化为活性更高的雌激素成分. 本文对膳食中的植物雌激素种类与资源分布、体内代谢以及代谢产物的种类和生理功能等进行综述, 旨在为植物雌激素微生物转化产物的研究和利用提供参考.

核心提要: 植物中广泛存在具有雌激素活性的天然成分. 存在于膳食中的天然植物雌激素被人或其他哺乳动物摄入体内后, 可被肠道菌群转化为活性更高的雌激素成分. 本文对膳食中的植物雌激素种类与分布、体内代谢以及代谢产物的种类和生理功能等进行综述.

引文著录: 王秀伶, 王烨. 膳食中的植物雌激素、肠道菌群与人类健康. 世界华人消化杂志 2016; 24(35): 4660-4676

Revised: June 3, 2016

Accepted: June 21, 2016

Published online: December 18, 2016

With the growth of age, the amount of estrogens produced by the human body will get less and less. Studies have shown that estrogen deficiency may cause many kinds of diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases, osteoporosis, and syndrome of menopause. Estrogens are also distributed extensively in numerous types of plants. Since there is a trace amount of natural estrogen in plants, our body can achieve continuous phytoestrogen supplementation while our health will not be influenced or damaged by the absorbed phytoestrogens in diets. After being absorbed, the phytoestrogens in diets may be converted by intestinal microflora to different metabolites with higher estrogenic activity. This review summarizes the types and distributions of phytoestrogens in diets, their metabolism, metabolites and bioactivities, with an aim to provide some guidelines for further study and utilization of microbial biotransforming metabolites of phytoestrogens.

- Citation: Wang XL, Wang Y. Dietary phytoestrogens, intestinal microflora and human health. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi 2016; 24(35): 4660-4676

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1009-3079/full/v24/i35/4660.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.11569/wcjd.v24.i35.4660

雌激素是由内分泌系统分泌的类固醇化合物, 雌激素水平与人体健康, 尤其是与女性健康有着密切联系. 随着年龄增长, 人体分泌的雌激素水平会逐渐下降, 导致雌激素水平不足, 进而引发心血管、骨质疏松以及更年期综合征等多种疾病, 目前报道的与雌激素相关的疾病多达上百种. 现有研究结果表明, 服用化学合成的雌激素药物对治疗骨质疏松、更年期综合征等内分泌代谢疾病有较好疗效, 几十年来雌激素替代疗法一直是许多雌激素分泌不足妇女的首选治疗方案. 然而, 化学合成的雌激素有严格的适应证和禁忌证, 长期不正确地通过化学雌激素药物来补充体内雌激素, 会大大增加患子宫内膜癌[1]、乳腺癌[2]以及心血管等疾病的风险[3]. 因此, 如何安全有效地补充体内雌激素已成为国内外研究的新热点.

植物雌激素(phytoestrogens)是一类在结构和功能上与动物雌激素类似, 但本身并非由动物分泌产生的一类天然活性物质. "Phytoestrogen"一词最早出现在1926年, 其中的"Phyto-"来自希腊语, 含义为"植物". 存在于植物中的天然雌激素通常含量低且不良反应小, 选用含有天然植物雌激素的植物作为膳食来补充体内雌激素, 不会对机体内分泌或其他功能造成冲击, 有目的选用含有植物雌激素的膳食来补充雌激素具有重要的现实意义.

尽管具有雌激素活性的天然产物在植物中广泛存在, "植物雌激素"这一概念的首次提出则仅仅是在90年前, 且当时人们并不清楚该类化合物是否对人类有益. 最近30年植物雌激素逐渐引起学术界的重视, 研究报道逐年增加, 植物雌激素的种类和功效也逐渐为人们所熟知. 然而, 值得一提的是, 人们目前对膳食中的植物雌激素被摄入体内后是否被代谢、代谢后生成哪些代谢产物以及这些代谢产物的活性如何了解得较少. 事实上, 植物雌激素被人体摄入体内后将面临被肠道微生物菌群代谢的命运[4]. 现有研究结果证实, 一些存在于植物体内具有弱雌激素活性的天然产物经肠道菌群代谢后, 生成了雌激素活性显著提高的新型微生物转化产物, 这些新型微生物转化产物大多在自然界中并不存在, 属非天然的天然同系物, 他们继承了其亲本化合物原有的天然产物的优点, 具有极大的研究和开发利用价值.

自1926年首次从植物中提取分离了雌激素类物质以来, 迄今已发现的植物雌激素有400多种, 其中以异黄酮、木脂素、二苯乙烯和香豆素类植物雌激素研究报道最多. 尽管异黄酮、木脂素、二苯乙烯和香豆素类植物雌激素在许多植物中均有分布, 但异黄酮以大豆中含量最为丰富, 木脂素在油料作物亚麻种子中以及药食两用植物牛蒡中含量最为丰富, 白藜芦醇是二苯乙烯类植物雌激素的代表性化合物, 在葡萄中含量最为丰富, 香豆素在大豆中含量较为丰富. 大豆、食用油、蔬菜和水果均为人类日常膳食种类, 以下将从膳食中的异黄酮和木脂素等植物雌激素的种类与资源分布、体内代谢以及代谢产物的种类和生理功能展开综述, 以期为植物雌激素微生物转化产物的研究与利用提供参考.

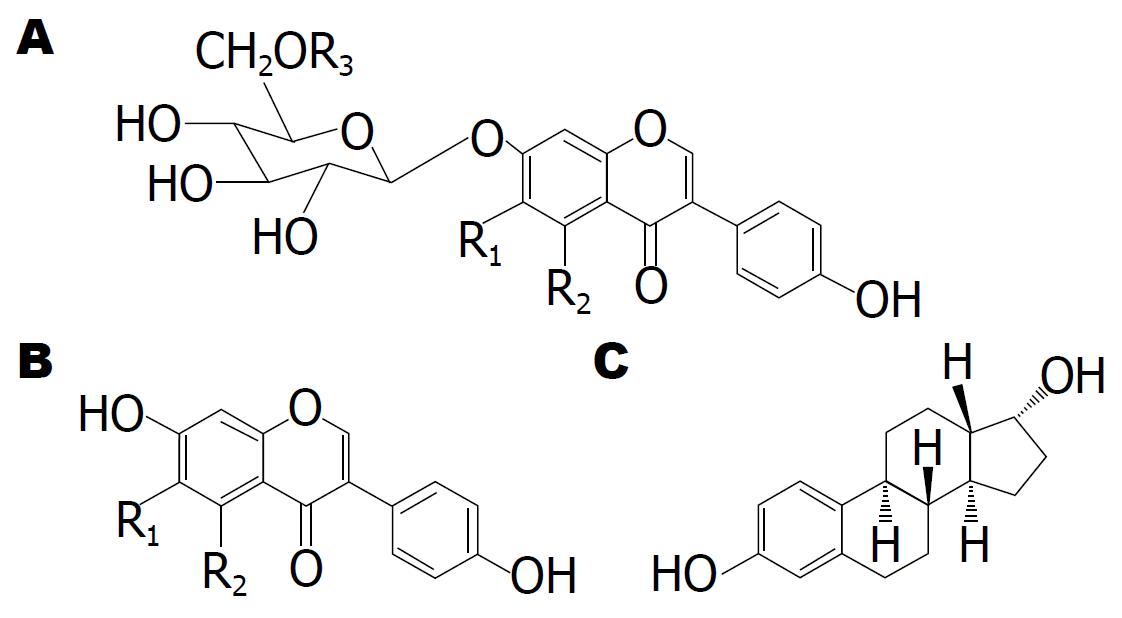

与黄酮类化合物的广泛分布不同, 异黄酮类化合物分布范围较窄, 仅分布于豆科植物蝶形花亚科的一些属中[5]. 异黄酮在大豆、葛根、苜蓿和三叶草中含量较高, 人体摄入的异黄酮则几乎全部来自大豆[6], 存在于大豆中的异黄酮又常被称为"大豆异黄酮"(soy isoflavones). 据报道, 大豆及大豆制品中异黄酮的含量为0.1%-0.5%, 其中以青豆中的含量最高, 其次是豆酱、豆芽、豆腐和豆奶等, 而在酱油中的含量则很低. 此外, 不同大豆品种其异黄酮含量相差较大, 相同大豆品种也会因为种植年份和种植区域的不同而导致异黄酮含量有所不同[7]. 异黄酮在大豆胚芽中含量最高, 是子叶中含量的6-10倍[8]. 目前已得到分离和结构鉴定的大豆异黄酮共12种, 包括游离型苷元和结合型糖苷两大类. 以游离形式存在的大豆异黄酮主要包括黄豆苷原(daidzein)、染料木素(genistein)和黄豆黄素(glycitein); 结合型糖苷包括葡萄糖苷、乙酰化糖苷和丙二酰化的糖苷(图1).

大豆异黄酮具有与人体雌激素雌二醇相似的化学结构(图1), 尤其表现为官能团4'-OH与7-OH之间极为相近的空间距离(11.5 Å), 因此又被称为具有雌激素活性的植物雌激素(phytoestrogens). 1986年美国科学家首先发现大豆中的异黄酮具有抑制癌细胞生长的作用, 1990年大豆异黄酮被确定为具有抗癌效果的最佳天然物质, 尤其对女性乳腺癌和男性前列腺癌具有很好的预防和治疗作用. 此后又证实, 大豆异黄酮具有减轻更年期不适症、减少骨质流失和降低心脑血管发病率等功效[9]. 流行病学研究表明, 东方人(尤其日本人和中国人)乳腺癌和前列腺癌的发病率远低于西方人, 这与东方人经常食用大豆制品有关, 特别是与大豆中含有的具有抗癌活性的大豆异黄酮有关. 据调查, 中国人和日本人平均每人每天从大豆及大豆制品中摄取的大豆异黄酮的含量约为40 mg/d, 韩国人每天从豆腐、豆酱、豆奶及豆芽中摄取的大豆异黄酮大约15 mg/d; 在西方多数国家, 大豆只被当作油制品或奶制品的原料, 平均每人每天摄取的大豆异黄酮的含量不足5 mg [10,11]. 根据美国著名营养学家Setchell[12]教授1999年报道, 美国人的日常饮食中异黄酮含量不足1 mg/d. 近年来, 随着大豆异黄酮的生理功能逐渐被阐明, 大豆被加工为西方人容易接受的大豆蛋白人造肉等, 在西方也悄悄兴起了豆制品消费热. 此外, 美国食品药品监督管理局还正式批准大豆为健康食品, 并建议其国民每人每天至少消费20-30 g大豆食品.

除大豆中分布的异黄酮类植物雌激素外, 在多数水果、蔬菜和谷物等膳食中均含有微量的木脂素类植物雌激素, 尽管含量不高, 但该类物质在日常保健中的作用却不容忽视. 木脂素又被称为木酚素, 在自然界中的分布非常广泛, 在许多油料作物种子(如亚麻籽、葵花子、芝麻籽等)、谷物(如小麦、黑麦、大麦、玉米、燕麦等)、蔬菜(如扁豆、茴香、洋葱等)和水果(如杏、黑莓、草莓等)中均有木脂素, 但以亚麻籽中的含量最高. 亚麻籽中的木脂素主要为开环异落叶松树脂酚二葡萄糖苷(secoisolariciresinol diglucoside, SDG). SDG除具有雌激素效应外, 还具有抗癌[13]、预防糖尿病[14,15]、降低体内脂质过氧化水平[16]、防止冠心病和动脉粥样硬化[17,18]等生理活性. Eliasson等[19]2003年通过高效液相色谱检测发现, 亚麻籽中的SDG含量为1.19%-2.59%. SDG经糖苷酶水解后可生成开环异落叶松脂醇(secoisolariciresinol, SECO). 此外, 分布于罗汉松科、松科、菊科、夹竹桃科等植物中的罗汉松脂素(matairesinol)、分布于十字花科、毛茛科、茜草科中的落叶松脂醇(lariciresinol, LAR)以及分布于杜仲科、瑞香科中的松脂醇(pinoresinol, PINO)均为含量较为丰富的木脂素化合物, 由于这些物质的化学结构与雌激素肠二醇或肠内酯相似, 因此, 人们在检测存在于膳食中的木脂素类植物雌激素时, 除SECO外, LAR和PINO等也通常作为检测指标.

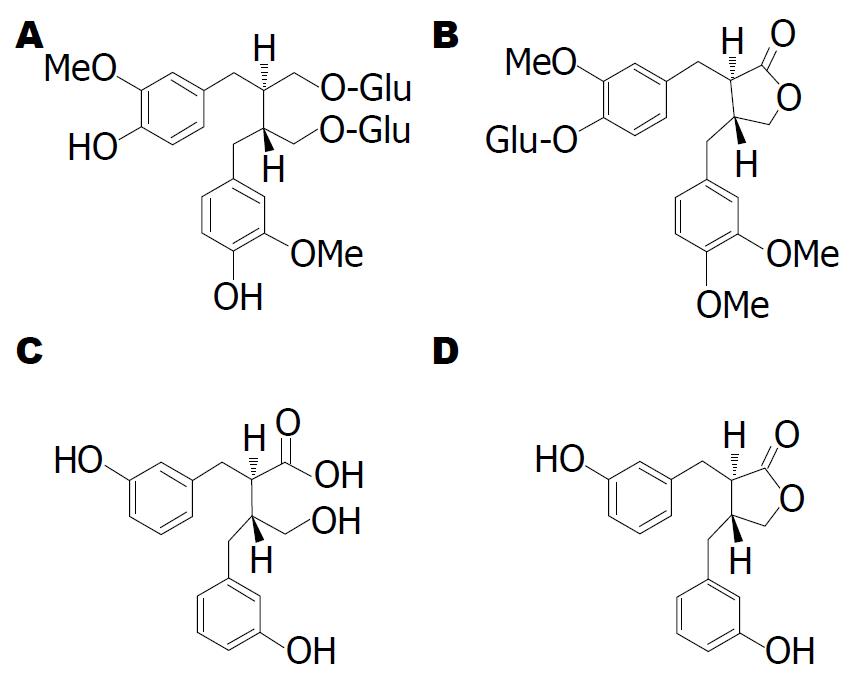

除了分布于亚麻种子中的SDG外, 木脂素还大量分布于药食两用植物牛蒡(Arctiumlappa L.)中. 牛蒡为菊科牛蒡属草本植物, 在全国各地均有分布. 牛蒡根、茎叶、果实均可供药用, 牛蒡的根和叶还可作为蔬菜食用, 有"东洋参"的美誉[20]. 牛蒡的干燥果实(即牛蒡子)是一种传统中药, 具有疏散风热、宣肺透疹、消肿解毒等功效. 牛蒡中的主要活性成分是牛蒡子苷(arctiin)和牛蒡苷元(arctigenin)[21], 其中牛蒡苷是牛蒡苷元与葡萄糖的结合型, 在体内葡萄糖苷酶[22]或酸水解下牛蒡苷可脱去葡萄糖生成牛蒡苷元[23]. 由于牛蒡苷元的化学结构与雌激素肠二醇和肠内酯相似(图2), 牛蒡苷元具有类似雌激素的活性. 此外, 现有研究结果证实, 牛蒡苷元还具有抗炎[24,25]、抗人类免疫缺陷病毒(human immunodeficiency virus, HIV)[26,27]、抗癌[28-30]、抗热休克反应[31]以及神经保护[32]等多种功效.

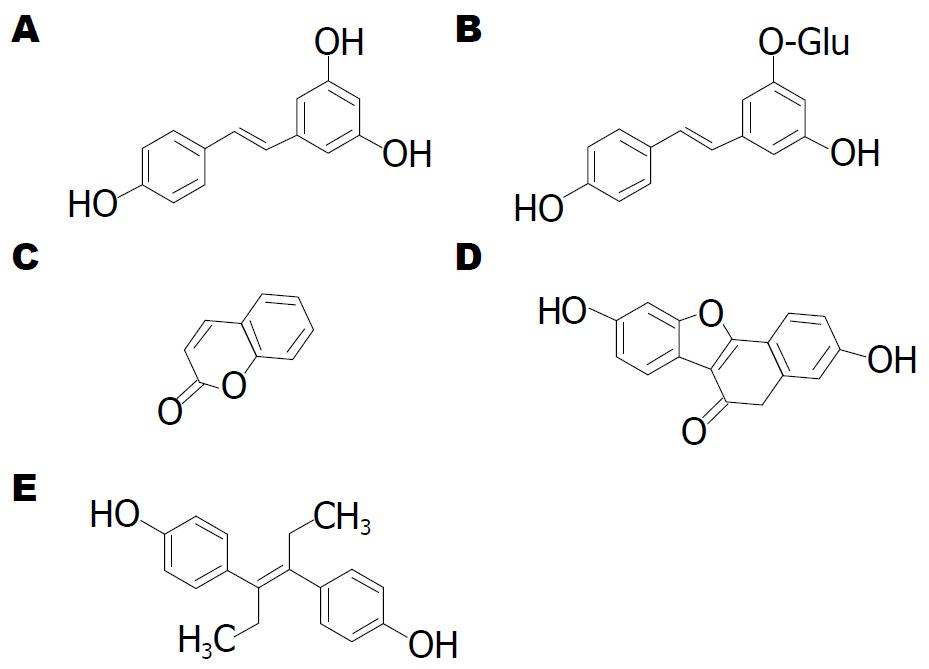

二苯乙烯类植物雌激素典型代表是白藜芦醇(resveratrol)和白藜芦醇苷(polydatin). 白藜芦醇1940年首次从毛叶藜芦根中分离得到, 广泛存在于葡萄科、百合科、蓼科、山毛榉科、桑科、豆科等70多种植物中, 其中以葡萄中的含量尤为丰富[33]. 白藜芦醇苷最早从传统中药虎杖中分离得到, 在虎杖、葡萄以及葡萄酒中, 白藜芦醇苷的含量远高于白藜芦醇. 白藜芦醇的化学结构与雌性激素己烯雌酚非常相似(图3), 可以竞争其受体的结合空间, 发挥雌激素效应. 此外, 白藜芦醇还具有抗菌[34,35]、抗癌[36,37]、抗氧化[38,39]、抗衰老[40,41]以及阻止血小板凝聚[42,43]等生理功能.

香豆素(coumarin)是一类结构中含有苯并α-吡喃酮母核(图3)的天然化合物的总称, 广泛存在于自然界中. 香豆素类化合物具有抗氧化[44,45]、抗HIV[46-48]、抗癌[49]以及降血压[50]等多种生理活性, 具有雌激素活性的香豆素类化合物则较少. 现有研究[51,52]结果证实, 香豆雌酚(coumestrol)是具有雌激素活性的香豆素类化合物, 膳食中的香豆素主要分布在豆科植物中, 其中以三叶草和豆芽中的含量最高. 香豆雌酚的化学结构与己烯雌酚相似, 表现为类似雌激素[53]或抗雌激素活性[54]. 此外, 香豆雌酚还具有抗癌[55]、预防骨质疏松症[56,57]、降血糖[58,59]、缓解由β-雌二醇引起的内皮组织依赖性冠状静脉舒张[60]和抑制SR12813对人体孕烷X受体活性的拮抗[61]等生理功能.

植物雌激素除存在于大豆及其制品中外, 还广泛存在于谷物、油料种子、坚果、蔬菜和水果中. 为了解植物雌激素的含量, 许多学者对不同植物以及来自不同植物的食物中的雌激素进行了定量分析[62,63]. 美国加州大学的Reinli和Block教授1996年对食物中的植物雌激素进行了很好的综述, 列举了94种植物中的29种植物雌激素成分, 并对豆腐、酱油、豆奶、豆芽、苜蓿芽等食物中的植物雌激素黄豆苷原、染料木素、芒柄花素(formononetin)、鹰嘴豆素(biochanin A)和香豆雌酚的含量进行对比分析, 但并不包括木脂素类化合物[64]. 英国学者Kuhnle等[65]2008年对茶、咖啡和酒精饮料以及坚果、种子和食用油等40种饮食中的植物雌激素成分进行了系统测定, 所测定化合物包括异黄酮类(黄豆苷原、染料木素、黄豆黄素、芒柄花素和鹰嘴豆素)、木脂素类(异落叶松脂醇和罗汉松脂素)和香豆雌酚. 由于在同一种膳食中可能既含有异黄酮成分又含有木脂素成分, 而之前的检测方法均不能同时对这两类植物雌激素进行检测. 为解决这一问题, 加拿大学者Thompson等[66]进行了深入研究, 并创建了能够同时检测异黄酮和木脂素的高效测定方法, 对包括黄豆、亚麻籽、西兰花、开心果、桃子、红酒等在内的121种食物、蔬菜、水果、坚果、饮料等中的异黄酮和木脂素进行了系统检测, 测定结果可为人们日常饮食提供重要指导. 表1列出了含量相对较高的膳食中的植物雌激素种类及含量.

| 样本 | DAI | GEN | LAR | PINO | SECO | COU | Total ISO | Total LIG |

| 豆制品 | ||||||||

| 黄豆 | 56621.4 | 44213.4 | 99.6 | 88.7 | 79.1 | 1.5 | 103649.3 | 269.2 |

| 豆腐 | 9337.5 | 17050.2 | 9.0 | 3.0 | 18.1 | 0.7 | 27118.5 | 30.9 |

| 豆奶 | 921.3 | 1852.2 | 4.9 | 1.6 | 5.7 | 0.6 | 2944.2 | 12.3 |

| 油料种子 | ||||||||

| 亚麻籽 | 58.2 | 173.2 | 2807.5 | 729.6 | 375321.9 | 46.8 | 321.4 | 379012.3 |

| 芝麻籽 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 1052.4 | 6814.5 | 7.3 | 0.4 | 10.5 | 7997.2 |

| 葵花籽 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 149.7 | 33.9 | 26.2 | 0.1 | 5.7 | 210.3 |

| 花生 | 1.7 | 4.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 25.3 | 0.1 | 7.3 | 27.1 |

| 坚果 | ||||||||

| 开心果 | 73.1 | 103.3 | 123.0 | 31.2 | 44.6 | 6.7 | 176.9 | 198.9 |

| 杏仁 | 2.1 | 14.4 | 32.2 | 9.0 | 70.3 | 1.5 | 18.0 | 111.7 |

| 腰果 | 1.4 | 10.3 | 60.5 | 1.1 | 37.5 | 0.4 | 22.1 | 99.4 |

| 栗子 | 2.8 | 16.4 | 7.8 | 5.6 | 172.7 | 2.4 | 21.2 | 186.6 |

| 核桃 | 35.2 | 16.4 | 7.2 | 0.2 | 78.0 | 0.6 | 53.3 | 85.7 |

| 蔬菜 | ||||||||

| 大蒜 | 5.0 | 14.3 | 54.4 | 481.9 | 42.0 | 0.1 | 20.3 | 583.2 |

| 苜蓿芽 | 1.7 | 7.5 | 24.1 | 18.4 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 394.1 | 44.8 |

| 羽衣甘蓝 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 66.7 | 24.8 | 5.9 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 97.8 |

| 西兰花 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 82.0 | 6.1 | 5.8 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 93.9 |

| 绿豆芽 | 91.4 | 135.2 | 18.5 | 13.1 | 97.0 | 136.6 | 229.8 | 128.7 |

| 水果 | ||||||||

| 桃子 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 9.5 | 37.1 | 13.6 | 0.1 | 2.6 | 61.8 |

| 草莓 | 0.3 | 2.1 | 22.9 | 20.8 | 5.1 | 0.3 | 2.4 | 48.9 |

| 干枣 | 1.2 | 3.4 | 116.9 | 100.2 | 106.2 | 0.8 | 5.1 | 323.6 |

| 杏脯 | 6.4 | 19.8 | 62.1 | 190.1 | 147.6 | 4.2 | 39.8 | 400.5 |

| 其他 | ||||||||

| 多谷面包 | 0.8 | 4.2 | 9.8 | 4.1 | 4770.4 | 0.5 | 12.6 | 4785.6 |

| 甘草糖 | 22.3 | 21.6 | 39.6 | 32.7 | 341.5 | 3.8 | 443.8 | 415.1 |

| 红酒 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 7.4 | 0.4 | 29.4 | 0.1 | 16.5 | 37.3 |

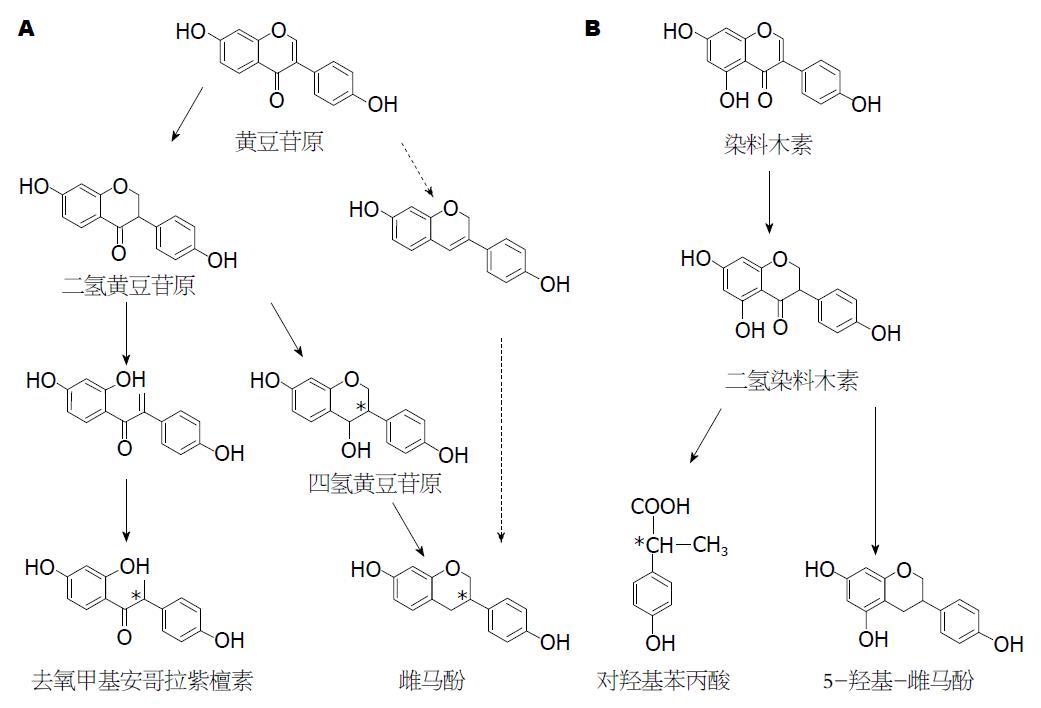

摄入机体内的天然植物雌激素面临被肠道微生物菌群降解的命运, 肠道菌群可通过去糖基、脱甲基、脱羟基以及还原反应等, 将摄入机体内的植物雌激素进行代谢. 1995年Xu等[67]通过将人粪样与大豆异黄酮共培养, 确定了肠道菌群对大豆异黄酮的代谢作用. Chang等[68]1995年的研究结果证实, 大豆异黄酮在厌氧条件下能被人体粪便中的微生物代谢, 其中黄豆苷原分别被转化为二氢黄豆苷原(dihydrodaidzein, DHD)和雌马酚(equol), 染料木素则被转化为二氢染料木素(dihydrogenistein, DHG). 1995年澳大利亚学者Joannou[69]与同事一起, 通过分析研究从人体尿液中检测到的各种不同代谢产物, 首次对大豆异黄酮在人体内的代谢途径进行推测, 这也是目前普遍受到公认的一条代谢途径. 1999年英国学者Coldham等[70]对染料木素在小鼠体内代谢进行研究, 并对染料木素代谢产物结构进行解析. Wang等[71]2004年发现人肠道细菌能将底物染料木素转化为对羟基-苯丙酸, Xie等[72]2015年报道了能将底物染料木素转化为左旋5-羟基-雌马酚(5-hydroxy-equol, 5-OH-EQ)的细菌菌株, 但有关染料木素在机体内的具体代谢途径目前尚不清楚(图4).

20世纪90年代末人们便开始分离对大豆异黄酮有不同转化功能的特定细菌菌株. 目前国内外分离报道的大豆异黄酮转化菌株有30余株. 根据报道的大豆异黄酮转化菌株的转化功能, 这些转化菌株分为三大类: 第I类具有加氢还原功能(C-2和C-3位), 该类菌株能将底物黄豆苷原或染料木素还原为DHD或DHG, 2000年Hur等[73]首次从人粪样中分离得到具有该类转化功能的革兰氏阳性厌氧菌HGH6. 此后, 又有学者从牛瘤胃胃液以及人粪样中分离了具有相同转化功能的细菌菌株(表2). 第Ⅱ类转化菌株具有开环转化功能, 能分别将底物黄豆苷原和染料木素开环转化为O-Dma和2-HPPA. 2002年Hur等[74]首次从人粪样中分离得到一株能将底物黄豆苷原开环转化为O-Dma的革兰氏阳性厌氧菌HGH136. 此后, Wang等[71]2004年从人粪样中分离了能将黄豆苷原和染料木素分别开环转化为O-Dma和2-HPPA的真杆菌属细菌菌株(表2). 第Ⅲ类是最重要的一类大豆异黄酮转化菌株, 该类菌株不仅能将底物黄豆苷原和染料木素进行加氢还原(C-2和C-3位), 同时能将底物的C-4酮基去掉. 2005年Wang等[75]从人粪样中分离得到一株能在厌氧条件下将底物DHD转化为雌马酚的革兰氏阴性爱格氏菌株Julong732, 这是世界上首株雌马酚产生菌, 通过手性分析, 发现菌株Julong732转化底物DHD后所生成的雌马酚为100%左旋S-型雌马酚. 从2006-2010的5年间, 来自日本、德国等国家的学者[76-98]陆续报道了能将底物DHD前体黄豆苷原转化为雌马酚的细菌菌株(表2). 2008年德国学者Braune带领团队首次报道了一株分自小鼠粪样能将黄豆苷原和染料木素分别转化为雌马酚和5-OH-EQ的红椿菌科细菌菌株MT1B8[76], 该团队于2009年又从人粪样菌群中分离得到一株能将染料木素转化为5-OH-EQ的细菌菌株HE8, 并根据其16S rDNA序列和相关生理生化特征将其命名为斯奈克菌属的一个新种, 即Slackia isoflavoniconvertens HE8[77], 但该团队并未对产物5-OH-EQ的旋光性进行分析报道. 王秀伶等[78]于2011年从鸡粪样中分离得到一株能将黄豆苷原转化为左旋S-型雌马酚, 同时也能将底物染料木素转化为左旋5-OH-EQ的斯奈克菌属菌株AUH-JLC159. 有关大豆异黄酮及其代谢产物的生物学活性最近几年渐有报道, 研究证实大豆异黄酮代谢产物具有比大豆异黄酮更高、更广的生物学活性. 由此可见, 大豆异黄酮对人的有益调节作用大小并不简单取决于摄入体内的大豆或豆制品的净含量的多少, 关键在于摄入体内的大豆异黄酮在肠道微生物菌群的作用下如何被转化, 即取决于定居在肠道的微生物种类.

| 底物 | 产物 | 转化菌株 | 菌源 | 作者 | 年份 |

| 芒柄花黄素 | DAI | Eubacterium limosum | 人类 | Hur等[79] | 2000 |

| 鹰嘴豆芽素A | GEN | Eubacterium limosum | |||

| 黄豆苷 | DAI | Escherichia coli | 人类 | Hur等[73] | 2000 |

| Bifidobacterium sp. | 人类 | Marotti等[80] | 2007 | ||

| 黄豆苷原 | DHD | Strain HGH6 | 人类 | Hur等[73] | 2000 |

| Lactobacillus sp. | 牛 | Wang等[81] | 2005 | ||

| 染料木苷 | GEN | Bifidobacterium sp. | 人类 | Marotti等[80] | 2007 |

| Escherichia coli | 人类 | Hur等[73] | 2000 | ||

| 染料木素 | DHG | Strain HGH6 | |||

| Lactobacillus sp. | 牛 | Wang等[81] | 2005 | ||

| 二氢黄豆苷原 | EQ | Eggerthella sp. | 人类 | Wang等[75] | 2005 |

| 黄豆苷原 | EQ | Asaccharobacter celatus | 大鼠 | Minamida等[82] | 2006 |

| Lactococcus garvieae | 人类 | Uchiyama等[88] | 2007 | ||

| Adlercreutzia equolifaciens | 人类 | Maruo等[83] | 2008 | ||

| Asaccharobactercelatus sp. | 大鼠 | Minamida等[84] | 2008 | ||

| Coriobacteriaceae sp. | 小鼠 | Matthies等[76] | 2008 | ||

| Eggerthella sp. | 人类 | Yokoyama等[85] | 2008 | ||

| Eubacterium sp. | 猪 | Yu等[86] | 2008 | ||

| Slackia isoflavoniconvertens | 人类 | Matthies等[77] | 2009 | ||

| Slackia equolifaciens | 人类 | Jin等[87] | 2009 | ||

| Slackia sp. | 人类 | Tsuji等[89] | 2010 | ||

| Proteus mirabilis | 大鼠 | 郭远洋等[90] | 2012 | ||

| 染料木素 | 5-OH-EQ | Strain DZE | 人类 | Jin等[91] | 2008 |

| Coriobacteriaceae sp. | 人类 | Matthies等[76] | 2008 | ||

| Slackia isoflavoniconvertens | 人类 | Matthies等[77] | 2009 | ||

| Slackia sp. | 鸡 | Wang等[78] | 2013 | ||

| 黄豆苷原 | O-Dma | Clostridium sp. | 人类 | Hur等[74] | 2002 |

| Eubacterium ramulus | 人类 | Schoefer等[92] | 2002 | ||

| Clostridium sp. | 鸡 | Li等[93] | 2015 | ||

| 染料木素 | 2-HPPA | Eubacterium ramulus | 人类 | Wang等[71] | 2004 |

| 牛蒡苷元 | DMAG | Eubacterium sp. | 人类 | Jin等[94] | 2007 |

| Peptostreptococcus sp. | 人类 | Wang等[95] | 2000 | ||

| 3'-DMAG | Blautia sp. | 人类 | Liu等[96] | 2013 | |

| 亚麻木酚素 | END | Peptostreptococcus sp. | 人类 | Wang等[95] | 2000 |

| Eubacterium sp. | |||||

| Clostridium saccharogumia | 人类 | Clavel等[97] | 2007 | ||

| Cactonifactor longoviformis | |||||

| ENL | Bacteroides distasonis | 人类 | Clavel等[98] | 2006 | |

| Bacteroides fragilis | |||||

| Bacteroides ovatus | |||||

| Clostridium cocleatum |

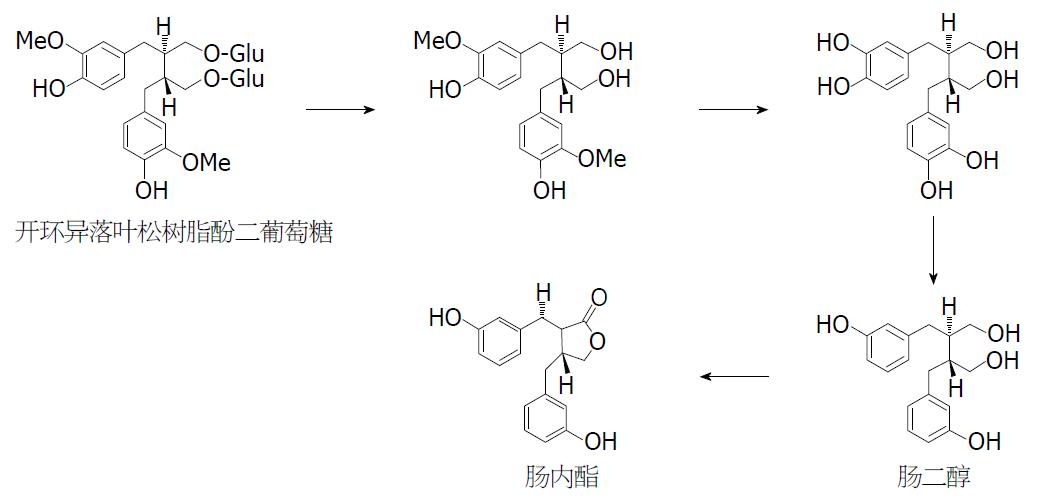

日本学者Hattori研究组将亚麻木脂素SDG与人粪样菌群共培养, 从培养液中分离得到包括肠二醇和肠内酯在内的7种SDG的转化产物. 此后, 该研究小组从人粪样菌群中分离了两株参与亚麻木脂素SDG代谢的细菌菌株(即Peptostreptococcus sp. SDG-1和Eubacterium sp. SDG-2), 但这两株细菌菌株只能将SDG转化为从SDG到肠内酯的中间代谢产物, 而不能将SDG或SDG的其他代谢产物转化为肠内酯[95]. 德国学者Clavel等[98]对亚麻木脂素SDG转化菌株进行了系统分离, 最终从人粪样菌群中分离得到4株参与亚麻木脂素SDG代谢的细菌菌株(即Clostridium saccharogumia, Eggerthella lenta, Blautia producta and Lactonifactor longoviformis), 当将这4株菌株与底物SDG进行混合培养时可得到肠二醇和肠内酯两种转化产物(图5), 但以肠二醇为主要代谢产物, 肠内酯含量则较低[95,99,100]. 肠二醇在哺乳动物体内可被转化为肠内酯, 但肠内酯不能被转化为肠二醇[101,102]. 值得一提的是, Hattori研究小组测定了亚麻木脂素SDG被菌群转化后生成的肠内酯的旋光性, 结果发现, 转化生成的肠内酯为右旋肠内酯[103], 有关SDG转化菌株的分离筛选目前国内尚未见报道.

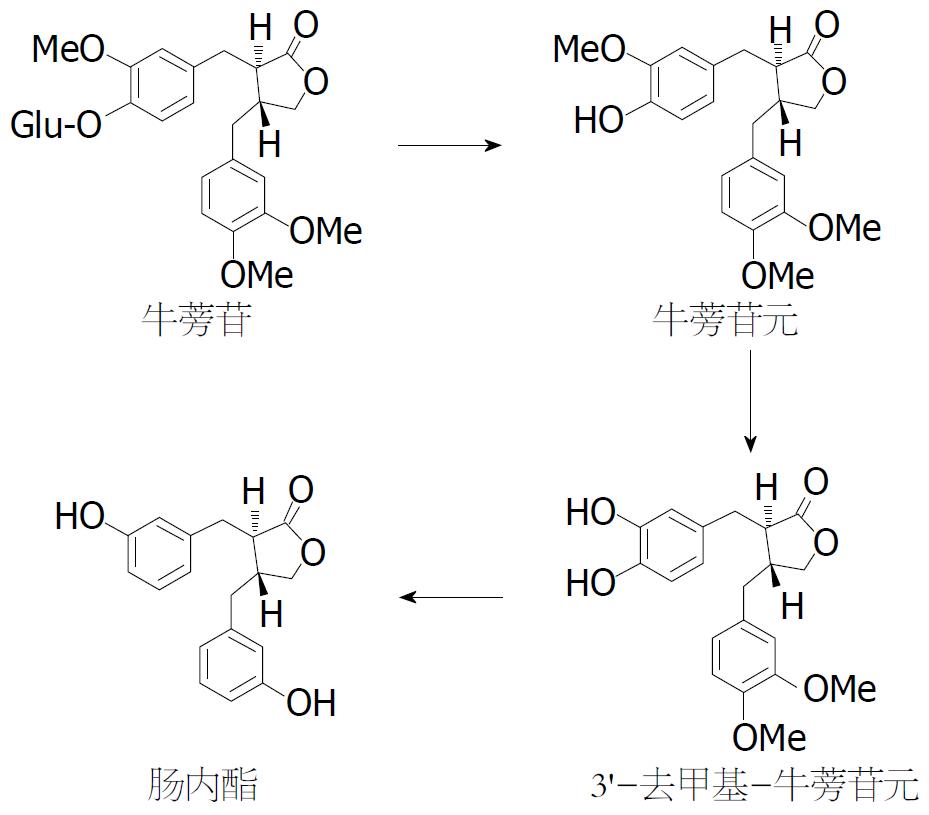

除亚麻木脂素外, 肠道菌群还可对药食两用植物牛蒡中的木脂素类化合物牛蒡苷和牛蒡苷元进行转化. 早在1992年, 日本学者Nose等[22]用小鼠的胃液和粪样菌群与牛蒡苷共培养, 发现底物牛蒡苷首先被脱掉葡萄糖基转化为牛蒡苷元, 牛蒡苷元进而被脱去甲基生成3'-去甲基-牛蒡苷元(3'-desmethylarctigenin, 3'-DMAG), 之后经过系列脱甲基和脱羟基作用, 最终生成肠内脂(图6). 此外, 我国辽宁中医药大学Wang等[104]2013年从小鼠粪便中分离得到3种牛蒡苷的代谢产物, 再次证明底物牛蒡苷可在小鼠体内被转化为不同代谢产物. 除了小鼠粪样菌群, 芬兰学者Heinonen等[105]2001年首次采用人粪样菌群与底物牛蒡苷共培养, 发现牛蒡苷可被转化为包括肠内酯在内的不同代谢产物, 但只有4%的牛蒡苷元可被转化为肠内酯. Hattori研究小组[106]于2003年将牛蒡苷与人肠道粪样菌群进行培养后, 从培养液中分离得到7种转化产物, 并根据转化产物的结构对牛蒡苷在人体内的代谢途径进行了推测(图6). 有关牛蒡苷转化菌株的分离筛选方面报道则相对较晚. 日本学者Jin等[94]2007年首次从人粪样中分离得到一株能将底物牛蒡苷元同时代谢为7种不同代谢产物的真细菌属菌株Eubacterium sp. ARC-2, 这是世界上报道的首株牛蒡苷或牛蒡苷元的转化菌株. Liu等[96]2013年报道了一株能将底物牛蒡苷或牛蒡苷元高效转化为3'-DMAG的布劳特氏菌属菌株.

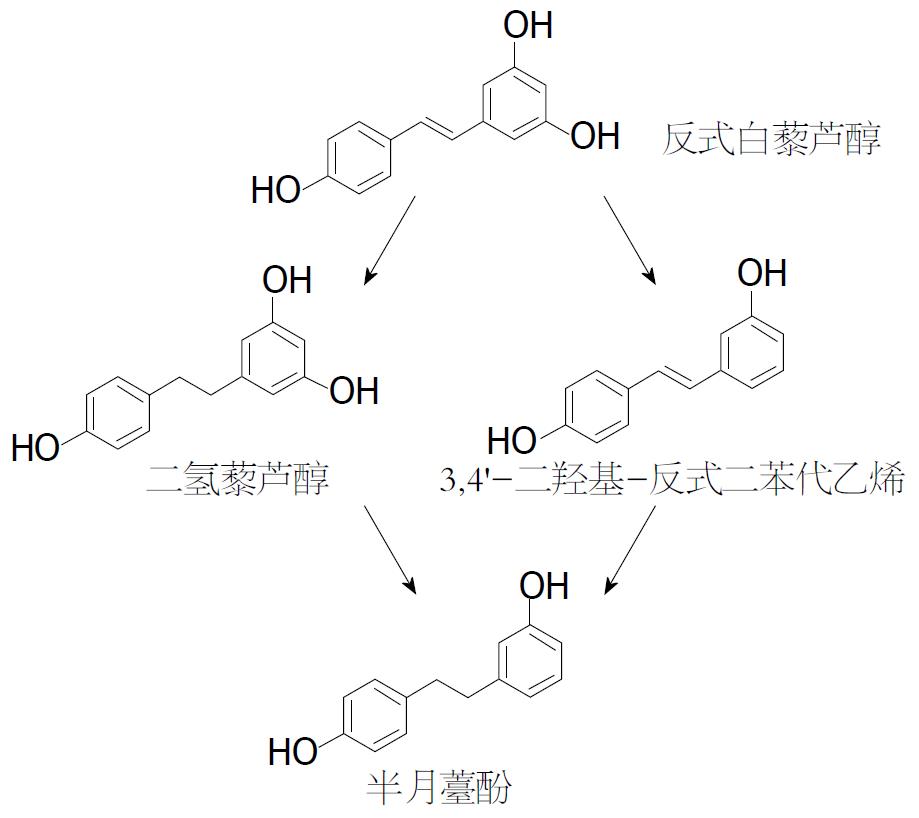

与大豆异黄酮和木脂素类植物雌激素相比, 有关二苯乙烯和香豆素类化合物的微生物生物转化研究报道相对较少. 2005-2011年研究人员分别从Wistar大鼠、猪和人体内检测到二氢藜芦醇等白藜芦醇的代谢物, 并且代谢物多以葡糖醛酸结合物和硫酸盐结合物的存在[107-110]. 2013年, 德国学者Bode等[111]用志愿者粪样菌群以及31株来自德国DSMZ菌种保藏中心的细菌菌株和10株作者从志愿者粪样中分离的细菌菌株, 对底物反式白藜芦醇进行转化研究. 结果发现, 志愿者的粪样菌群均可将底物白藜芦醇转化为二氢白藜芦醇(dihydroresveratrol)、3,4'-二羟基-反式二苯代乙烯(3,4'-dihydroxy-trans-stilbene)和半月薹酚(lunularin)三种代谢物, 其中以半月薹酚的生成量最多, 3,4'-二羟基-反式二苯代乙烯的生成量最少[111]. 因此, 推测白藜芦醇既可被还原为二氢白藜芦醇, 同时又可去羟基生成3,4-二羟基-反式二苯代乙烯, 而这两种中间代谢产物均可被转化为半月薹酚(图7). 通过单菌转化实验发现, 只有来自菌库的S. equolifaciens和A. equolifaciens能将反式白藜芦醇还原为二氢白藜芦醇. 此外, 2014年Menet等[112]发现在灵长类动物狐猴体内, 有白藜芦醇和二氢藜芦醇以及二者的葡糖醛酸结合物和硫酸盐结合物的存在, 其中亲水性白藜芦醇结合物有6种、亲水性二氢藜芦醇的结合物有3种, 这表明白藜芦醇被还原为二氢藜芦醇后被吸收和代谢.

与上述植物雌激素类化合物相比, 香豆素代谢研究报道最少. 香豆素类化合物被机体摄入体内可被转化为二氢香豆素(dihydrocoumarin)、羟基-香豆素(hydroxycoumarin)和邻香豆酸(o-coumaric acid)以及与葡萄糖醛酸的结合物[113-115], 然而, 香豆素类化合物在不同动物内代谢存在明显不同. 香豆素类化合物在人体内迅速代谢为7-羟基香豆素(7-hydroxycoumarin), 7-羟基-香豆素和邻香豆酸是香豆素在人体内的主要代谢产物[116,117], 而在大鼠和兔子体内则主要被代谢为邻香豆酸[118,119]. 因此, 内酯环水解可能是香豆素在体内代谢的一条途径.

雌马酚[7-hydroxy-3-(4'-hydroxyphenyl)-chroman]最早是由Marrian和Haselwood 于1932年在马尿中发现[120]. 1982年美国著名营养学家Setchell研究团队[121]首次在人尿中检测到了雌马酚. 在大豆异黄酮所有代谢产物中, 雌马酚的化学结构与人体雌激素雌二醇最为接近, Setchell等[122,123]首次确定了雌马酚的雌激素作用, 并预言雌马酚将在雌激素相关疾病以及临床中发挥作用. 由于雌马酚的C-3为手性碳, 因而雌马酚具有R-型和S-型两种对映异构体. Muthyala等[124]2004年对雌马酚对映异构体与雌激素受体的亲和力进行了研究, 发现S-雌马酚对人体雌激素受体β(β-estrogen receptor, ERβ)的亲和力要比R-雌马酚高13倍、比消旋体雌马酚(±Equol)高2倍; 相反, R-雌马酚对人体雌激素受体α(α-estrogen receptor, ERα)的亲和力要比S-雌马酚高4倍、比外消旋体雌马酚(±Equol)高两倍, 而相对雌马酚而言, 其前体黄豆苷原和DHD与雌激素受体亲和力则较弱[125,126]. Wang等[75] 2005年报道由人肠道细菌菌株Eggerthella sp. Julong732转化底物DHD所生成的雌马酚为100% S-雌马酚, 美国营养学家Setchell团队[127]2005年经检测发现人体内的雌马酚也全部为S-雌马酚. 为强调雌马酚在大豆异黄酮众多微生物转化产物中的重要地位, Setchell等[128]还将人群定义为两类, 一类为能产生雌马酚的人群(equol-producer), 另一类为不能产生雌马酚的人群(non-equol-producer). 事实上, 人群中仅30%左右的个体能将黄豆苷原转化为雌马酚[129]. 在大豆或豆制品摄入量高的地方的人群中, 大约30%-60%的个体能将底物黄豆苷原转化为雌马酚[130].

除雌激素活性外, 雌马酚还具有抗氧化、抗癌、减少骨质流失以及降低心脑血管发病率等多种功效. 有研究[131]报道, 雌马酚的抗氧化活性是其亲本化合物黄豆苷原的100多倍. Liang等[132]2010年对比研究了大豆异黄酮及其微生物转化产物对超氧阴离子和DPPH自由基的清除能力, 发现在供试的所有化合物中, 雌马酚对超氧阴离子和DPPH自由基清除能力显著高于大豆异黄酮黄豆苷原及大豆异黄酮的其他微生物转化产物. 近年来, 有关雌马酚活性研究报道最多的是其抗癌活性, 其中以与雌激素相关的癌症, 如乳腺癌[133-135]和前列腺癌[136,137]报道得最多. 最近研究结果表明, 雌马酚对癌细胞的抑制能力大小具有细胞选择性. 与乳腺癌和前列腺癌细胞系相比, 雌马酚对人肝癌细胞SMMC-7721的抑制作用则更强, 推测雌马酚对作用敏感细胞的选择性可能与癌细胞系受体种类直接相关[138]. 此外, 与大豆异黄酮相比, 雌马酚具有更高的生物利用度. 与其亲本化合物黄豆苷原相比, 雌马酚更容易被肠壁吸收[139], 而且在血液中的半衰期也明显长于黄豆苷原和染料木素[140]. 需指出的是, 以往有关雌马酚活性的研究大多使用化学合成的外消旋体雌马酚, 今后应加强R-型、S-型以及外消旋体雌马酚的对比研究.

人类起初对雌激素的认识源于雌激素引发的不良反应. 20世纪40年代, 澳大利亚西部羊群由于长期食用三叶草而导致生殖能力下降[141], 这也是人类首次发现一些可以发挥类似动物体内雌激素功效的植物源化合物[142]. 目前, 有关大豆异黄酮活性的文献有3000篇以上, 尽管其中有极少数关于大豆异黄酮对人[143]或动物[144]的不良作用的报道, 绝大部分研究结果均证实了大豆异黄酮的有益调节作用. 事实上, 大豆异黄酮及其微生物代谢产物究竟发挥有益还是有害作用与其浓度直接相关. Zhang等[145]2014年的研究结果表明, 合适浓度的5-OH-EQ(<0.4 mmol/L)可显著延长秀丽隐杆线虫的平均寿命和抗热能力, 但5-OH-EQ浓度过高(0.8 mmol/L)则显著缩短线虫寿命. 因此, 在进行大豆异黄酮及其代谢产物活性测定时, 一定要严格考察不同浓度的影响, 并以此作为治疗或保健用参考指标.

除雌马酚外, 黄豆苷原经肠道菌群代谢后生成的另一个终产物为O-Dma. 现有研究[146,147]结果证实, O-Dma与人体雌激素受体ERα和ERβ的亲和力高于其亲本化合物黄豆苷原, 表明O-Dma的雌激素活性高于黄豆苷原. 另外, 当O-Dma与ERβ结合后, 在诱导基因转录上O-Dma也明显强于黄豆苷原[146]. 2008年日本学者Ohtomo等[148]比较了O-Dma与雌马酚对切除子宫小鼠的骨密度及代谢的影响, 发现O-Dma促进脂类物质的正常代谢, 抑制破骨细胞生长, O-Dma表现出的有利于减少骨质流失的生理活性可能与其类雌激素活性有关. 此外, O-Dma还可抑制类固醇激素代谢中的一些酶, 如: 芳香酶、5α-还原酶、17β-羟基类固醇脱氢酶[149-151]; 当浓度高于10 μmol/L时, O-Dma还能够明显抑制人乳腺癌细胞MCF-7的生长[152]. 值得一提的是, 目前O-Dma尚不能进行人工化学合成, 而由微生物菌株转化底物黄豆苷原生成的O-Dma则表现出不同的对映体过量率, 但均以左旋O-Dma为优势产物. 分自人粪样的真杆菌属菌株Julong601转化底物黄豆苷原后生成的O-Dma的对映体过量率为90.0%[71], 分自鸡粪样的梭菌属菌株AUH-JLC108转化生成的O-Dma的对映体过量率为88.3%[93], 分自褐马鸡的肠球菌属菌株AUH-HM195转化生成的O-Dma的对映体过量率则仅为66.9%[153]. 而对于O-Dma的两个对映异构体是否具有不同的生物学活性, 或者其中一个对映异构体是否有某种或某些不良反应目前尚不清楚, 今后应加强对O-Dma单一对映体活性的研究.

尽管木脂素广泛存在于各种蔬菜、水果、种子及谷物中, 但木脂素类化合物只有被肠道菌群代谢后才能被吸收和利用[154]. 木脂素对人类的有益调节作用主要归功于其代谢产物肠二醇和肠内酯, 有研究[155]报道, 肠二醇和肠内酯的抗氧化活性高于其亲本化合物SDG. 此外, 肠内酯对激素相关疾病, 如乳腺癌[156,157]和前列腺癌[158,159]、妇女绝经期综合征[160,161]、心血管疾病[162-164]以及骨质疏松[165]等均具有很好预防和治疗作用. 由于肠内脂的酚醛结构, 可有效对抗DNA氧化损伤及脂质过氧化反应[166]. 此外, 肠内酯可选择性地抑制LNCaP前列腺癌细胞的生长, 引发细胞凋亡[167]. 肠内酯诱导的细胞凋亡是通过线粒体膜电位的损失、剂量依赖的细胞色素c的释放和多聚腺苷二磷酸-核糖聚合酶(PARP)合成量的改变等来实现. 此外, 肠内脂还影响成骨细胞分化[168]和影响人的肥胖与代谢[169]. 需指出的是, 通过旋光性测定人们发现, 牛蒡子中的牛蒡苷为左旋[即(-)-牛蒡苷], 经哺乳动物粪样菌群转化后生成的肠内酯为左旋肠内酯[即(-)-肠内酯][102]; 存在于油料作物亚麻籽中的木酚素SDG为右旋[即(+)-SDG], 经哺乳动物粪样菌群转化后生成的肠内酯为右旋肠内酯[即(+)-肠内酯][106]. 目前有关肠内酯活性的报道大多为化学合成的肠内酯, 有关(-)-肠内酯和(+)-肠内酯在生物学活性方面差异有必要进行深入研究, 研究结果对指导人们正确摄食木脂素类化合物, 保持身体健康将具有重要意义.

膳食中的天然植物雌激素对人类的有益调节作用大小, 取决于膳食中的植物雌激素在肠道菌群作用下如何被代谢. 与亲本化合物大豆异黄酮相比, 雌马酚与雌激素受体ER的亲和力更高, 在不同雌激素水平下可发挥类雌激素或抗雌激素的双向调节功能, 并在荷尔蒙依赖相关疾病的治疗和预防中发挥重要作用. 另外, 雌马酚表现出的生物利用度和抗氧化活性远高于其亲本化合物, 在与氧化应激相关的疾病的治疗中也将发挥重要作用. 木脂素虽广泛存在于人们的日常饮食中, 但未经肠道菌群代谢的木脂素很难被人体直接吸收利用, 木脂素发挥有益调节作用需要肠道菌群的参与. 木脂素代谢产物肠内酯将在与雌激素相关的癌症、骨质疏松以及心脑血管疾病的预防和治疗中发挥重要作用. 为使体内雌激素水平得到源源不断的补充, 日常膳食应尽可能食用豆制品以及富含木脂素的蔬菜、水果和谷物.

"植物雌激素"概念的首次提出是1926年, 而人类对植物雌激素生理活性的报道最早出现在20世纪40年代, 是始于由植物雌激素引发的动物生殖能力的下降. 然而, 随着人类对植物雌激素研究的不断深入, 报道更多的则是植物雌激素对人类的有益调节作用, 目前有关植物雌激素以及植物雌激素在机体内的代谢已成为国内外研究的热点.

新型植物雌激素的发现及其在体内的代谢、已知天然植物雌激素在体内的代谢以及具有转化功能的特定微生物菌株的分离、已知天然植物雌激素微生物转化产物的药理、毒理和药代动力学等是该领域亟待研究的问题.

2010年美国学者Patisaul HB和Jefferson W从植物雌激素的摄入水平、体内代谢以及在体内发挥作用的方式等方面, 对植物雌激素的利与弊进行了报道.

本文系统阐述了膳食中的植物雌激素种类、含量与资源分布、植物雌激素在机体内的代谢、转化菌株种类及代谢途径以及植物雌激素主要代谢产物的生理功能.

天然植物雌激素微生物转化产物在绿色高附加值保健食品及新药研发中应用前景广阔.

微生物生物转化: 由微生物产生的某一种或某几种酶对底物特定部位所进行的催化反应, 通过微生物生物转化可将复杂的底物进行结构修饰.

谭周进, 教授, 湖南中医药大学

肠道菌群对动物通过消化道摄入成分的转化及其产生的生理功能, 是目前研究的一个热点, 本文对膳食中植物雌激素的种类及生理功能、肠道菌群对植物雌激素的代谢以及植物雌激素的微生物转化产物与人类健康进行了综述, 具有较好的意义.

手稿来源: 邀请约稿

学科分类: 胃肠病学和肝病学

手稿来源地: 河北省

同行评议报告分类

A级 (优秀): 0

B级 (非常好): B

C级 (良好): 0

D级 (一般): 0

E级 (差): 0

编辑: 郭鹏 电编:李瑞芳

| 1. | Bandera EV, Williams MG, Sima C, Bayuga S, Pulick K, Wilcox H, Soslow R, Zauber AG, Olson SH. Phytoestrogen consumption and endometrial cancer risk: a population-based case-control study in New Jersey. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:1117-1127. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 2. | Kotepui M. Diet and risk of breast cancer. Contemp Oncol (Pozn). 2016;20:13-19. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 3. | Reger MK, Zollinger TW, Liu Z, Jones J, Zhang J. Urinary phytoestrogens and cancer, cardiovascular, and all-cause mortality in the continuous National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Eur J Nutr. 2016;55:1029-1040. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 4. | 刘 明杰, 林 琳, 王 钊. 肠道细菌对天然药物代谢的研究进展Ⅰ. 中国现代应用药学杂志. 2001;18:90-92. |

| 5. | Harborne JB. The flavonoids. London: Chapman and Hall Ltd 1988; 125-204. |

| 6. | Coward L, Barnes NC, Setchell KDR, Barnes S. Genistein, daidzein and their β-glycoside conjugates: antitumor isoflavones in soybean foods from American and Asian diets. J Agri Food Chem. 1993;41:1961-1967. [DOI] |

| 7. | Wang HJ, Murphy PA. Isoflavones composition of American and Japanese soybeans in Lowa: effects of variety, crop year and location. J Agri Food Chem. 1994;42:1674-1677. [DOI] |

| 8. | Tani T, Katsuki T, Kubo M, Arichi S, Kitagawa I. Histochemistry: Isoflavones in soybeans (Glycine max MERRILL, seeds). Chem Pharm Bull. 1985;33:3834-3837. [DOI] |

| 9. | Chin-Dusting JP, Fisher LJ, Lewis TV, Piekarska A, Nestel PJ, Husband A. The vascular activity of some isoflavone metabolites: implications for a cardioprotective role. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;133:595-605. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Wakai K, Egami I, Kato K, Kawamura T, Tamakoshi A, Lin Y, Nakayama T, Wada M, Ohno Y. Dietary intake and sources of isoflavones among Japanese. Nutr Cancer. 1999;33:139-145. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Kim J, Kwon C. Estimated dietary isoflavone intake of Korean population based on National Nutrition Survey. Nutr Res. 2001;21:947-953. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 12. | Setchell KD, Cassidy A. Dietary isoflavones: biological effects and relevance to human health. J Nutr. 1999;129:758S-767S. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Dikshit A, Gao C, Small C, Hales K, Hales DB. Flaxseed and its components differentially affect estrogen targets in pre-neoplastic hen ovaries. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2016;159:73-85. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 14. | Adolphe JL, Whiting SJ, Juurlink BH, Thorpe LU, Alcorn J. Health effects with consumption of the flax lignan secoisolariciresinol diglucoside. Br J Nutr. 2010;103:929-938. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 15. | Prasad K. Secoisolariciresinol diglucoside from flaxseed delays the development of type 2 diabetes in Zucker rat. J Lab Clin Med. 2001;138:32-39. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Prasad K. Oxidative stress as a mechanism of diabetes in diabetic BB prone rats: effect of secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG). Mol Cell Biochem. 2000;209:89-96. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Penumathsa SV, Koneru S, Zhan L, John S, Menon VP, Prasad K, Maulik N. Secoisolariciresinol diglucoside induces neovascularization-mediated cardioprotection against ischemia-reperfusion injury in hypercholesterolemic myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44:170-179. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Penumathsa SV, Koneru S, Thirunavukkarasu M, Zhan L, Prasad K, Maulik N. Secoisolariciresinol diglucoside: relevance to angiogenesis and cardioprotection against ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320:951-959. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Eliasson C, Kamal-Eldin A, Andersson R, Aman P. High-performance liquid chromatographic analysis of secoisolariciresinol diglucoside and hydroxycinnamic acid glucosides in flaxseed by alkaline extraction. J Chromatogr A. 2003;1012:151-159. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Nose M, Fujimoto T, Takeda T, Nishibe S, Ogihara Y. Structural transformation of lignan compounds in rat gastrointestinal tract. Planta Med. 1992;58:520-523. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 24. | Chae SH, Kim PS, Cho JY, Park JS, Lee JH, Yoo ES, Baik KU, Lee JS, Park MH. Isolation and identification of inhibitory compounds on TNF-alpha production from Magnolia fargesii. Arch Pharm Res. 1998;21:67-69. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Zhao F, Wang L, Liu K. In vitro anti-inflammatory effects of arctigenin, a lignan from Arctium lappa L., through inhibition on iNOS pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;122:457-462. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 26. | Schröder HC, Merz H, Steffen R, Müller WE, Sarin PS, Trumm S, Schulz J, Eich E. Differential in vitro anti-HIV activity of natural lignans. Z Naturforsch C. 1990;45:1215-1221. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Vlietinck AJ, De Bruyne T, Apers S, Pieters LA. Plant-derived leading compounds for chemotherapy of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Planta Med. 1998;64:97-109. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 28. | Kato T, Hirose M, Takahashi S, Hasegawa R, Kohno T, Nishibe S, Kato K, Shirai T. Effects of the lignan, arctiin, on 17-beta ethinyl estradiol promotion of preneoplastic liver cell foci development in rats. Anticancer Res. 1998;18:1053-1057. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Huang DM, Guh JH, Chueh SC, Teng CM. Modulation of anti-adhesion molecule MUC-1 is associated with arctiin-induced growth inhibition in PC-3 cells. Prostate. 2004;59:260-267. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 30. | Yang S, Ma J, Xiao J, Lv X, Li X, Yang H, Liu Y, Feng S, Zhang Y. Arctigenin anti-tumor activity in bladder cancer T24 cell line through induction of cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis. Anat Rec (Hoboken). 2012;295:1260-1266. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 31. | Ishihara K, Yamagishi N, Saito Y, Takasaki M, Konoshima T, Hatayama T. Arctigenin from Fructus Arctii is a novel suppressor of heat shock response in mammalian cells. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2006;11:154-161. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 32. | Jang YP, Kim SR, Kim YC. Neuroprotective dibenzylbutyrolactone lignans of Torreya nucifera. Planta Med. 2001;67:470-472. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Kong Q, Ren X, Hu R, Yin X, Jiang G, Pan Y. Isolation and purification of two antioxidant isomers of resveratrol dimer from the wine grape by counter-current chromatography. J Sep Sci. 2016; Apr 30. [Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 36. | Chimento A, Sirianni R, Saturnino C, Caruso A, Sinicropi MS, Pezzi V. Resveratrol and Its Analogs As Antitumoral Agents For Breast Cancer Treatment. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2016;16:699-709. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 37. | Serrero G, Lu R. Effect of resveratrol on the expression of autocrine growth modulators in human breast cancer cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2001;3:969-979. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Cavallini G, Straniero S, Donati A, Bergamini E. Resveratrol Requires Red Wine Polyphenols for Optimum Antioxidant Activity. J Nutr Health Aging. 2016;20:540-545. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 39. | Jang M, Cai L, Udeani GO, Slowing KV, Thomas CF, Beecher CW, Fong HH, Farnsworth NR, Kinghorn AD, Mehta RG. Cancer chemopreventive activity of resveratrol, a natural product derived from grapes. Science. 1997;275:218-220. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Kilic Eren M, Kilincli A, Eren Ö. Resveratrol induced premature senescence is associated with DNA damage mediated SIRT1 and SIRT2 down-regulation. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124837. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 41. | Xia N, Daiber A, Förstermann U, Li H. Antioxidant effects of resveratrol in the cardiovascular system. Br J Pharmacol. 2016; Apr 5. [Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 42. | Toliopoulos IK, Simos YV, Oikonomidis S, Karkabounas SC. Resveratrol diminishes platelet aggregation and increases susceptibility of K562 tumor cells to natural killer cells. Indian J Biochem Biophys. 2013;50:14-18. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Fylaktakidou KC, Hadjipavlou-Litina DJ, Litinas KE, Nicolaides DN. Natural and synthetic coumarin derivatives with anti-inflammatory/ antioxidant activities. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:3813-3833. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 45. | Rajarajeswari N, Pari L. Antioxidant role of coumarin on streptozotocin-nicotinamide-induced type 2 diabetic rats. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2011;25:355-361. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 46. | Kashman Y, Gustafson KR, Fuller RW, Cardellina JH, McMahon JB, Currens MJ, Buckheit RW, Hughes SH, Cragg GM, Boyd MR. The calanolides, a novel HIV-inhibitory class of coumarin derivatives from the tropical rainforest tree, Calophyllum lanigerum. J Med Chem. 1992;35:2735-2743. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 47. | Bourinbaiar AS, Tan X, Nagorny R. Effect of the oral anticoagulant, warfarin, on HIV-1 replication and spread. AIDS. 1993;7:129-130. [PubMed] |

| 48. | Kostova I. Coumarins as inhibitors of HIV reverse transcriptase. Curr HIV Res. 2006;4:347-363. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 49. | Kostova I. Synthetic and natural coumarins as cytotoxic agents. Curr Med Chem Anticancer Agents. 2005;5:29-46. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 50. | Wei EH, Rao MR, Chen XY, Fan LM, Chen Q. Inhibitory effects of praeruptorin C on cattle aortic smooth muscle cell proliferation. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2002;23:129-132. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Wang G, Kuan SS, Francis OJ, Ware GM, Carman AS. A simplified HPLC method for the determination of phytoestrogens in soybean and its processed products. J Agric Food Chem. 1990;38:185-190. [DOI] |

| 52. | Franke AA, Custer LJ, Cerna CM, Narala KK. Quantitation of phytoestrogens in legumes by HPLC. J Agric Food Chem. 1994;42:1905-1913. [DOI] |

| 53. | Ndebele K, Graham B, Tchounwou PB. Estrogenic activity of coumestrol, DDT, and TCDD in human cervical cancer cells. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7:2045-2056. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 54. | Jacob DA, Temple JL, Patisaul HB, Young LJ, Rissman EF. Coumestrol antagonizes neuroendocrine actions of estrogen via the estrogen receptor alpha. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2001;226:301-306. [PubMed] |

| 55. | Diel P, Olff S, Schmidt S, Michna H. Effects of the environmental estrogens bisphenol A, o,p'-DDT, p-tert-octylphenol and coumestrol on apoptosis induction, cell proliferation and the expression of estrogen sensitive molecular parameters in the human breast cancer cell line MCF-7. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;80:61-70. [PubMed] |

| 56. | Sun JS, Li YY, Liu MH, Sheu SY. Effects of coumestrol on neonatal and adult mice osteoblasts activities. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;81:214-223. [PubMed] |

| 57. | Wu XT, Wang B, Wei JN. Coumestrol promotes proliferation and osteoblastic differentiation in rat bone marrow stromal cells. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2009;90:621-628. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 58. | Nogowski L, Nowak KW, Kaczmarek P, Maćkowiak P. The influence of coumestrol, zearalenone, and genistein administration on insulin receptors and insulin secretion in ovariectomized rats. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2002;22:449-457. [PubMed] |

| 59. | Nogowski L, Nowak KW, Maćkowiak P. Effect of phytooestrogen--coumestrol and oestrone on some aspects of carbohydrate metabolism in ovariectomized female rats. Arch Vet Pol. 1992;32:79-84. [PubMed] |

| 60. | Kane MO, Anselm E, Rattmann YD, Auger C, Schini-Kerth VB. Role of gender and estrogen receptors in the rat aorta endothelium-dependent relaxation to red wine polyphenols. Vascul Pharmacol. 2009;51:140-146. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 61. | Wang H, Li H, Moore LB, Johnson MD, Maglich JM, Goodwin B, Ittoop OR, Wisely B, Creech K, Parks DJ. The phytoestrogen coumestrol is a naturally occurring antagonist of the human pregnane X receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:838-857. [PubMed] |

| 62. | Eldridge AC, Kwolek WF. Soybean isoflavones: effect of environment and variety on composition. J Agric Food Chem. 1993;31:394-396. [PubMed] |

| 63. | Barnes S, Coward L, Kirk M, Sfakianos J. HPLC-mass spectrometry analysis of isoflavones. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1998;217:254-262. [PubMed] |

| 64. | Reinli K, Block G. Phytoestrogen content of foods--a compendium of literature values. Nutr Cancer. 1996;26:123-148. [PubMed] |

| 65. | Kuhnle GG, Dell'Aquila C, Aspinall SM, Runswick SA, Mulligan AA, Bingham SA. Phytoestrogen content of beverages, nuts, seeds, and oils. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:7311-7315. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 66. | Thompson LU, Boucher BA, Liu Z, Cotterchio M, Kreiger N. Phytoestrogen content of foods consumed in Canada, including isoflavones, lignans, and coumestan. Nutr Cancer. 2006;54:184-201. [PubMed] |

| 67. | Xu X, Harris KS, Wang HJ, Murphy PA, Hendrich S. Bioavailability of soybean isoflavones depends upon gut microflora in women. J Nutr. 1995;125:2307-2315. [PubMed] |

| 68. | Chang YC, Nair MG. Metabolism of daidzein and genistein by intestinal bacteria. J Nat Prod. 1995;58:1892-1896. [PubMed] |

| 69. | Joannou GE, Kelly GE, Reeder AY, Waring M, Nelson C. A urinary profile study of dietary phytoestrogens. The identification and mode of metabolism of new isoflavonoids. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;54:167-184. [PubMed] |

| 70. | Coldham NG, Howells LC, Santi A, Montesissa C, Langlais C, King LJ, Macpherson DD, Sauer MJ. Biotransformation of genistein in the rat: elucidation of metabolite structure by product ion mass fragmentology. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1999;70:169-184. [PubMed] |

| 71. | Wang XL, Kim KT, Lee JH, Hur HG, Kim SI. C-ring cleavage of isoflavones daidzein and genistein by a newly isolated human intestinal bacterium Eubacterium ramulus Julong 601. J Microbiol Biotechn. 2004;14:766-771. |

| 72. | Xie YJ, Liu ZG, Gao YN, Wang XL, Hao QH, Yu XM. Bioconversion of genistein to (-)5-hydroxyequol by a newly isolated cock intestinal anaerobic bacterium. J Chin Pharm Sci. 2015;24:442-448. [DOI] |

| 73. | Hur HG, Lay JO, Beger RD, Freeman JP, Rafii F. Isolation of human intestinal bacteria metabolizing the natural isoflavone glycosides daidzin and genistin. Arch Microbiol. 2000;174:422-428. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 74. | Hur HG, Beger RD, Heinze TM, Lay JO, Freeman JP, Dore J, Rafii F. Isolation of an anaerobic intestinal bacterium capable of cleaving the C-ring of the isoflavonoid daidzein. Arch Microbiol. 2002;178:8-12. [PubMed] |

| 75. | Wang XL, Hur HG, Lee JH, Kim KT, Kim SI. Enantioselective synthesis of S-equol from dihydrodaidzein by a newly isolated anaerobic human intestinal bacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:214-219. [PubMed] |

| 76. | Matthies A, Clavel T, Gütschow M, Engst W, Haller D, Blaut M, Braune A. Conversion of daidzein and genistein by an anaerobic bacterium newly isolated from the mouse intestine. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:4847-4852. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 77. | Matthies A, Blaut M, Braune A. Isolation of a human intestinal bacterium capable of daidzein and genistein conversion. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:1740-1744. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 78. | 王 秀伶, 刘 子光, 邵 子强. 斯奈克氏菌AUH-JLC159及其在左旋-5-OH-EQ生物合成中的应用. 中国专利 2013-09-04. . |

| 79. | Hur H, Rafii F. Biotransformation of the isoflavonoids biochanin A, formononetin, and glycitein by Eubacterium limosum. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;192:21-25. [PubMed] |

| 80. | Marotti I, Bonetti A, Biavati B, Catizone P, Dinelli G. Biotransformation of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) flavonoid glycosides by bifidobacterium species from human intestinal origin. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:3913-3919. [PubMed] |

| 81. | Wang XL, Shin KH, Hur HG, Kim SI. Enhanced biosynthesis of dihydrodaidzein and dihydrogenistein by a newly isolated bovine rumen anaerobic bacterium. J Biotechnol. 2005;115:261-269. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 82. | Minamida K, Tanaka M, Abe A, Sone T, Tomita F, Hara H, Asano K. Production of equol from daidzein by gram-positive rod-shaped bacterium isolated from rat intestine. J Biosci Bioeng. 2006;102:247-250. [PubMed] |

| 83. | Maruo T, Sakamoto M, Ito C, Toda T, Benno Y. Adlercreutzia equolifaciens gen. nov., sp. nov., an equol-producing bacterium isolated from human faeces, and emended description of the genus Eggerthella. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2008;58:1221-1227. [PubMed] |

| 84. | Minamida K, Ota K, Nishimukai M, Tanaka M, Abe A, Sone T, Tomita F, Hara H, Asano K. Asaccharobacter celatus gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from rat caecum. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2008;58:1238-1240. [PubMed] |

| 85. | Yokoyama S, Suzuki T. Isolation and characterization of a novel equol-producing bacterium from human feces. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2008;72:2660-2666. [PubMed] |

| 86. | Yu ZT, Yao W, Zhu WY. Isolation and identification of equol-producing bacterial strains from cultures of pig faeces. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;282:73-80. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 87. | Jin JS, Kitahara M, Sakamoto M, Hattori M, Benno Y. Slackia equolifaciens sp. nov., a human intestinal bacterium capable of producing equol. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60:1721-1724. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 88. | Uchiyama S, Ueno T, Suzuki T. Identification of a newly isolated equol-producing lactic acid bacterium from the human feces (In Japanese). J Enteric Bacteria. 2007;21:217-220. |

| 89. | Tsuji H, Moriyama K, Nomoto K, Miyanaga N, Akaza H. Isolation and characterization of the equol-producing bacterium Slackia sp. strain NATTS. Arch Microbiol. 2010;192:279-287. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 91. | Jin JS, Nishihata T, Kakiuchi N, Hattori M. Biotransformation of C-glucosylisoflavone puerarin to estrogenic (3S)-equol in co-culture of two human intestinal bacteria. Biol Pharm Bull. 2008;31:1621-1625. [PubMed] |

| 92. | Schoefer L, Mohan R, Braune A, Birringer M, Blaut M. Anaerobic C-ring cleavage of genistein and daidzein by Eubacterium ramulus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;208:197-202. [PubMed] |

| 93. | Li M, Li H, Zhang C, Wang XL, Chen BH, Hao QH, Wang SY. Enhanced biosynthesis of O-desmethylangolensin from daidzein by a novel oxygen-tolerant cock intestinal bacterium in the presence of atmospheric oxygen. J Appl Microbiol. 2015;118:619-628. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 94. | Jin JS, Zhao YF, Nakamura N, Akao T, Kakiuchi N, Hattori M. Isolation and characterization of a human intestinal bacterium, Eubacterium sp. ARC-2, capable of demethylating arctigenin, in the essential metabolic process to enterolactone. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30:904-911. [PubMed] |

| 95. | Wang LQ, Meselhy MR, Li Y, Qin GW, Hattori M. Human intestinal bacteria capable of transforming secoisolariciresinol diglucoside to mammalian lignans, enterodiol and enterolactone. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo). 2000;48:1606-1610. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 96. | Liu MY, Li M, Wang XL, Liu P, Hao QH, Yu XM. Study on human intestinal bacterium Blautia sp. AUH-JLD56 for the conversion of arctigenin to (-)-3'-desmethylarctigenin. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61:12060-12065. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 97. | Clavel T, Lippman R, Gavini F, Doré J, Blaut M. Clostridium saccharogumia sp. nov. and Lactonifactor longoviformis gen. nov., sp. nov., two novel human faecal bacteria involved in the conversion of the dietary phytoestrogen secoisolariciresinol diglucoside. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2007;30:16-26. [PubMed] |

| 98. | Clavel T, Henderson G, Engst W, Doré J, Blaut M. Phylogeny of human intestinal bacteria that activate the dietary lignan secoisolariciresinol diglucoside. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2006;55:471-478. [PubMed] |

| 99. | Clavel T, Henderson G, Alpert CA, Philippe C, Rigottier-Gois L, Doré J, Blaut M. Intestinal bacterial communities that produce active estrogen-like compounds enterodiol and enterolactone in humans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:6077-6085. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 100. | Clavel T, Borrmann D, Braune A, Doré J, Blaut M. Occurrence and activity of human intestinal bacteria involved in the conversion of dietary lignans. Anaerobe. 2006;12:140-147. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 101. | Jin JS, Kakiuchi N, Hattori M. Enantioselective oxidation of enterodiol to enterolactone by human intestinal bacteria. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30:2204-2206. [PubMed] |

| 102. | Jin JS, Hattori M. Further studies on a human intestinal bacterium Ruminococcus sp. END-1 for transformation of plant lignans to mammalian lignans. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:7537-7542. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 103. | Xie LH, Ahn EM, Akao T, Abdel-Hafez AA, Nakamura N, Hattori M. Transformation of arctiin to estrogenic and antiestrogenic substances by human intestinal bacteria. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo). 2003;51:378-384. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 104. | Wang W, Pan Q, Han XY, Wang J, Tan RQ, He F, Dou DQ, Kang TG. Simultaneous determination of arctiin and its metabolites in rat urine and feces by HPLC. Fitoterapia. 2013;86:6-12. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 105. | Heinonen S, Nurmi T, Liukkonen K, Poutanen K, Wähälä K, Deyama T, Nishibe S, Adlercreutz H. In vitro metabolism of plant lignans: new precursors of mammalian lignans enterolactone and enterodiol. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:3178-3186. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 106. | Jin JS, Zhao YF, Nakamura N, Akao T, Kakiuchi N, Min BS, Hattori M. Enantioselective dehydroxylation of enterodiol and enterolactone precursors by human intestinal bacteria. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30:2113-2119. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 107. | Wenzel E, Soldo T, Erbersdobler H, Somoza V. Bioactivity and metabolism of trans-resveratrol orally administered to Wistar rats. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2005;49:482-494. [PubMed] |

| 108. | Cottart CH, Nivet-Antoine V, Laguillier-Morizot C, Beaudeux JL. Resveratrol bioavailability and toxicity in humans. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2010;54:7-16. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 109. | Azorín-Ortuño M, Yáñez-Gascón MJ, Vallejo F, Pallarés FJ, Larrosa M, Lucas R, Morales JC, Tomás-Barberán FA, García-Conesa MT, Espín JC. Metabolites and tissue distribution of resveratrol in the pig. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2011;55:1154-1168. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 110. | Zunino SJ, Storms DH. Physiological levels of resveratrol metabolites are ineffective as anti-leukemia agents against Jurkat leukemia cells. Nutr Cancer. 2015;67:266-274. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 111. | Bode LM, Bunzel D, Huch M, Cho GS, Ruhland D, Bunzel M, Bub A, Franz CM, Kulling SE. In vivo and in vitro metabolism of trans-resveratrol by human gut microbiota. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97:295-309. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 112. | Menet MC, Marchal J, Dal-Pan A, Taghi M, Nivet-Antoine V, Dargère D, Laprévote O, Beaudeux JL, Aujard F, Epelbaum J. Resveratrol metabolism in a non-human primate, the grey mouse lemur (Microcebus murinus), using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole time of flight. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91932. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 113. | Gasparetto JC, de Francisco TM, Campos FR, Pontarolo R. Development and validation of two methods based on high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry for determining 1,2-benzopyrone, dihydrocoumarin, o-coumaric acid, syringaldehyde and kaurenoic acid in guaco extracts and pharmaceutical preparations. J Sep Sci. 2011;34:740-748. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 114. | Bogan DP, O'Kennedy R. Simultaneous determination of coumarin, 7-hydroxycoumarin and 7-hydroxycoumarin glucuronide in human serum and plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr B Biomed Appl. 1996;686:267-273. [PubMed] |

| 115. | Egan DA, O'Kennedy R. Rapid and sensitive determination of coumarin and 7-hydroxycoumarin and its glucuronide conjugate in urine and plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1992;582:137-143. [PubMed] |

| 116. | Booth AN, Masri MS, Robbins DJ, Emerson OH, Jones FT, Deeds F. Urinary metabolites of coumarin and omicron-coumaric acid. J Biol Chem. 1959;234:946-948. [PubMed] |

| 117. | Gasparetto JC, Peccinini RG, de Francisco TM, Cerqueira LB, Campos FR, Pontarolo R. A kinetic study of the main guaco metabolites using syrup formulation and the identification of an alternative route of coumarin metabolism in humans. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0118922. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 118. | Lake BG. Coumarin metabolism, toxicity and carcinogenicity: relevance for human risk assessment. Food Chem Toxicol. 1999;37:423-453. [PubMed] |

| 119. | Lacy A, O'Kennedy R. Studies on coumarins and coumarin-related compounds to determine their therapeutic role in the treatment of cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:3797-3811. [PubMed] |

| 120. | Marrian GF, Haslewood GA. Equol, a new inactive phenol isolated from the ketohydroxyoestrin fraction of mares' urine. Biochem J. 1932;26:1227-1232. [PubMed] |

| 121. | Axelson M, Kirk DN, Farrant RD, Cooley G, Lawson AM, Setchell KD. The identification of the weak oestrogen equol [7-hydroxy-3-(4'-hydroxyphenyl)chroman] in human urine. Biochem J. 1982;201:353-357. [PubMed] |

| 122. | Setchell KD, Borriello SP, Hulme P, Kirk DN, Axelson M. Nonsteroidal estrogens of dietary origin: possible roles in hormone-dependent disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 1984;40:569-578. [PubMed] |

| 123. | Setchell KD, Brown NM, Lydeking-Olsen E. The clinical importance of the metabolite equol-a clue to the effectiveness of soy and its isoflavones. J Nutr. 2002;132:3577-3584. [PubMed] |

| 124. | Muthyala RS, Ju YH, Sheng S, Williams LD, Doerge DR, Katzenellenbogen BS, Helferich WG, Katzenellenbogen JA. Equol, a natural estrogenic metabolite from soy isoflavones: convenient preparation and resolution of R- and S-equols and their differing binding and biological activity through estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Bioorg Med Chem. 2004;12:1559-1567. [PubMed] |

| 125. | Lehmann L, Esch HL, Wagner J, Rohnstock L, Metzler M. Estrogenic and genotoxic potential of equol and two hydroxylated metabolites of Daidzein in cultured human Ishikawa cells. Toxicol Lett. 2005;158:72-86. [PubMed] |

| 126. | Cassidy A. Dietary phyto-oestrogens: molecular mechanisms, bioavailability and importance to menopausal health. Nutr Res Rev. 2005;18:183-201. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 127. | Setchell KD, Clerici C, Lephart ED, Cole SJ, Heenan C, Castellani D, Wolfe BE, Nechemias-Zimmer L, Brown NM, Lund TD. S-equol, a potent ligand for estrogen receptor beta, is the exclusive enantiomeric form of the soy isoflavone metabolite produced by human intestinal bacterial flora. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:1072-1079. [PubMed] |

| 128. | Setchell KD, Brown NM, Summer S, King EC, Heubi JE, Cole S, Guy T, Hokin B. Dietary factors influence production of the soy isoflavone metabolite s-(-)equol in healthy adults. J Nutr. 2013;143:1950-1958. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 129. | Slavin JL, Karr SC, Hutchins AM, Lampe JW. Influence of soybean processing, habitual diet, and soy dose on urinary isoflavonoid excretion. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:1492S-1495S. [PubMed] |

| 130. | Rafii F. The role of colonic bacteria in the metabolism of the natural isoflavone daidzin to equol. Metabolites. 2015;5:56-73. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 131. | Rimbach G, De Pascual-Teresa S, Ewins BA, Matsugo S, Uchida Y, Minihane AM, Turner R, VafeiAdou K, Weinberg PD. Antioxidant and free radical scavenging activity of isoflavone metabolites. Xenobiotica. 2003;33:913-925. [PubMed] |

| 132. | Liang XL, Wang XL, Li Z, Hao QH, Wang SY. Improved in vitro assays of superoxide anion and 1,1-diphenyl- 2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical-scavenging activity of isoflavones and isoflavone metabolites. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:11548-11552. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 133. | Choi EJ, Kim T. Equol induced apoptosis via cell cycle arrest in human breast cancer MDA-MB-453 but not MCF-7 cells. Mol Med Rep. 2008;1:239-244. [PubMed] |

| 134. | Choi EJ, Ahn WS, Bae SM. Equol induces apoptosis through cytochrome c-mediated caspases cascade in human breast cancer MDA-MB-453 cells. Chem Biol Interact. 2009;177:7-11. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 135. | Charalambous C, Pitta CA, Constantinou AI. Equol enhances tamoxifen's anti-tumor activity by induction of caspase-mediated apoptosis in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:238. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 136. | Szliszka E, Krol W. Soy isoflavones augment the effect of TRAIL-mediated apoptotic death in prostate cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2011;26:533-541. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 137. | Zheng W, Zhang Y, Ma D, Shi Y, Liu C, Wang P. (±)Equol inhibits invasion in prostate cancer DU145 cells possibly via down-regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-9, matrix metalloproteinase-2 and urokinase-type plasminogen activator by antioxidant activity. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2012;51:61-67. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 138. | Liang XL, Li M, Li J, Wang XL. Equol induces apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma SMMC-7721 cells through the intrinsic pathway and the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway. Anticancer Drugs. 2014;25:633-640. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 139. | Zubik L, Meydani M. Bioavailability of soybean isoflavones from aglycone and glucoside forms in American women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:1459-1465. [PubMed] |

| 140. | Decroos K, Vanhemmens S, Cattoir S, Boon N, Verstraete W. Isolation and characterisation of an equol-producing mixed microbial culture from a human faecal sample and its activity under gastrointestinal conditions. Arch Microbiol. 2005;183:45-55. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 141. | Bennetts HW, Underwood EJ, Shier FL. A specific breeding problem of sheep on subterranean clover pastures in Western Australia. Aust Vet J. 1946;22:2-12. [PubMed] |

| 142. | Rossiter RC, Beck AB. Physiological and ecological studies on the estrogenic isoflavones in subterranean clover (Trifolium subterraneum) I. effects of temperature. Aust J Agric Res. 1966;17:29-37. |

| 143. | Petrakis NL, Barnes S, King EB, Lowenstein J, Wiencke J, Lee MM, Miike R, Kirk M, Coward L. Stimulatory influence of soy protein isolate on breast secretion in pre- and postmenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1996;5:785-794. [PubMed] |

| 144. | Cerundolo R, Michel KE, Court MH, Shrestha B, Refsal KR, Oliver JW, Biourge V, Shofer FS. Effects of dietary soy isoflavones on health, steroidogenesis, and thyroid gland function in dogs. Am J Vet Res. 2009;70:353-360. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 145. | Zhang CH, Wang XL, Liang XL, Zhang HL, Hao QH. Effects of (-)-5-hydroxyequol on the lifespan and stress resistance of Caenorhabditis elegans. J Chin Pharm Sci. 2014;23:378-384. |

| 146. | Kinjo J, Tsuchihashi R, Morito K, Hirose T, Aomori T, Nagao T, Okabe H, Nohara T, Masamune Y. Interactions of phytoestrogens with estrogen receptors alpha and beta (III). Estrogenic activities of soy isoflavone aglycones and their metabolites isolated from human urine. Biol Pharm Bull. 2004;27:185-188. [PubMed] |

| 147. | Morito K, Hirose T, Kinjo J, Hirakawa T, Okawa M, Nohara T, Ogawa S, Inoue S, Muramatsu M, Masamune Y. Interaction of phytoestrogens with estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Biol Pharm Bull. 2001;24:351-356. [PubMed] |

| 148. | Ohtomo T, Uehara M, Peñalvo JL, Adlercreutz H, Katsumata S, Suzuki K, Takeda K, Masuyama R, Ishimi Y. Comparative activities of daidzein metabolites, equol and O-desmethylangolensin, on bone mineral density and lipid metabolism in ovariectomized mice and in osteoclast cell cultures. Eur J Nutr. 2008;47:273-279. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 149. | Evans BA, Griffiths K, Morton MS. Inhibition of 5 alpha-reductase in genital skin fibroblasts and prostate tissue by dietary lignans and isoflavonoids. J Endocrinol. 1995;147:295-302. [PubMed] |

| 150. | Pelissero C, Lenczowski MJ, Chinzi D, Davail-Cuisset B, Sumpter JP, Fostier A. Effects of flavonoids on aromatase activity, an in vitro study. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;57:215-223. [PubMed] |

| 151. | Adlercreutz H, Bannwart C, Wähälä K, Mäkelä T, Brunow G, Hase T, Arosemena PJ, Kellis JT, Vickery LE. Inhibition of human aromatase by mammalian lignans and isoflavonoid phytoestrogens. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1993;44:147-153. [PubMed] |

| 152. | Schmitt E, Dekant W, Stopper H. Assaying the estrogenicity of phytoestrogens in cells of different estrogen sensitive tissues. Toxicol In Vitro. 2001;15:433-439. [PubMed] |

| 153. | 于 飞, 王 世英, 李 佳, 张 琪, 李 朝东, 王 秀伶. 兼性肠球菌 Enterococcus hirae AUH-HM195对黄豆苷原的开环转化. 微生物学报. 2009;49:479-484. |

| 154. | Landete JM. Plant and mammalian lignans: A review of source, intake, metabolism, intestinal bacteria and health. Food Res Int. 2012;46:410-424. [DOI] |

| 155. | Kitts DD, Yuan YV, Wijewickreme AN, Thompson LU. Antioxidant activity of the flaxseed lignan secoisolariciresinol diglycoside and its mammalian lignan metabolites enterodiol and enterolactone. Mol Cell Biochem. 1999;202:91-100. [PubMed] |

| 156. | Power KA, Saarinen NM, Chen JM, Thompson LU. Mammalian lignans enterolactone and enterodiol, alone and in combination with the isoflavone genistein, do not promote the growth of MCF-7 xenografts in ovariectomized athymic nude mice. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1316-1320. [PubMed] |

| 157. | Mabrok HB, Klopfleisch R, Ghanem KZ, Clavel T, Blaut M, Loh G. Lignan transformation by gut bacteria lowers tumor burden in a gnotobiotic rat model of breast cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:203-208. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 158. | Saarinen NM, Tuominen J, Pylkkänen L, Santti R. Assessment of information to substantiate a health claim on the prevention of prostate cancer by lignans. Nutrients. 2010;2:99-115. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 159. | Chen LH, Fang J, Li H, Demark-Wahnefried W, Lin X. Enterolactone induces apoptosis in human prostate carcinoma LNCaP cells via a mitochondrial-mediated, caspase-dependent pathway. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:2581-2590. [PubMed] |

| 160. | Mueller SO, Simon S, Chae K, Metzler M, Korach KS. Phytoestrogens and their human metabolites show distinct agonistic and antagonistic properties on estrogen receptor alpha (ERalpha) and ERbeta in human cells. Toxicol Sci. 2004;80:14-25. [PubMed] |

| 161. | Penttinen P, Jaehrling J, Damdimopoulos AE, Inzunza J, Lemmen JG, van der Saag P, Pettersson K, Gauglitz G, Mäkelä S, Pongratz I. Diet-derived polyphenol metabolite enterolactone is a tissue-specific estrogen receptor activator. Endocrinology. 2007;148:4875-4886. [PubMed] |

| 162. | Kilkkinen A, Erlund I, Virtanen MJ, Alfthan G, Ariniemi K, Virtamo J. Serum enterolactone concentration and the risk of coronary heart disease in a case-cohort study of Finnish male smokers. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:687-693. [PubMed] |

| 163. | Rodriguez-Leyva D, Dupasquier CM, McCullough R, Pierce GN. The cardiovascular effects of flaxseed and its omega-3 fatty acid, alpha-linolenic acid. Can J Cardiol. 2010;26:489-496. [PubMed] |

| 164. | Cardozo LF, Vicente GC, Brant LH, Mafra D, Chagas MA, Boaventura GT. Prolonged flaxseed flour intake decreased the thickness of the aorta and modulates some modifiable risk factors related to cardiovascular disease in rats. Nutr Hosp. 2014;29:376-381. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 165. | Kardinaal AF, Morton MS, Brüggemann-Rotgans IE, van Beresteijn EC. Phyto-oestrogen excretion and rate of bone loss in postmenopausal women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1998;52:850-855. [PubMed] |

| 166. | Hu C, Yuan YV, Kitts DD. Antioxidant activities of the flaxseed lignan secoisolariciresinol diglucoside, its aglycone secoisolariciresinol and the mammalian lignans enterodiol and enterolactone in vitro. Food Chem Toxicol. 2007;45:2219-2227. [PubMed] |

| 167. | McCann MJ, Rowland IR, Roy NC. The anti-proliferative effects of enterolactone in prostate cancer cells: evidence for the role of DNA licencing genes, mi-R106b cluster expression, and PTEN dosage. Nutrients. 2014;6:4839-4855. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 168. | Feng J, Shi Z, Ye Z. Effects of metabolites of the lignans enterolactone and enterodiol on osteoblastic differentiation of MG-63 cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2008;31:1067-1070. [PubMed] |