修回日期: 2009-06-23

接受日期: 2009-06-23

在线出版日期: 2009-07-18

目的: 探讨血清IL-18和IL-1β水平在慢性丙型肝炎患者病程进展中的作用及与临床和干扰素疗效的关系.

方法: 检测30例慢性丙型肝炎患者干扰素治疗前后血清IL-18和IL-1β含量, 观察HCV感染后不同阶段血清IL-18和IL-1β水平的变化, 分析血清IL-18和IL-1β水平与ALT水平、HCV基因型及Th1/Th2相关细胞因子IL-2和IL-6的关系. 比较应答组和无应答组之间2种细胞因子水平的差异. 血清细胞因子检测应用ELISA法, HCV基因分型应用直接测序法, HCV RNA载量采用荧光定量PCR法.

结果: 慢性丙型肝炎患者血清IL-18水平明显高于健康对照组(1077.44±657.58 ng/L vs 259.92±328.47 ng/L, P<0.001), IL-1β水平与健康对照组无显著差异; 随着感染时间的延长, 血清IL-1β水平有逐渐升高趋势, 而IL-18则逐渐下降; 慢性肝炎重度患者血清IL-1β水平明显高于轻度患者(4.99±1.44 ng/L vs 3.68±0.76 ng/L, P<0.05); 不同基因型和亚型之间两种细胞因子水平无显著差异; 血清IL-18与IL-2含量呈显著性正相关(r = 0.434, P<0.05), 与IL-6无相关, 血清IL-1β含量与IL-2和IL-6均无相关; 干扰素对应答组和无应答组治疗前、后血清IL-18和IL-1β水平均无显著性差异.

结论: 血清IL-18和IL-1β水平分别与丙型肝炎的慢性化和病情轻重相关, 该两种细胞因子水平与干扰素疗效无关, 不能对疗效进行预测.

引文著录: 张琳, 苗亮, 付海超, 赵桂珍, 冯国和, 窦晓光. 慢性丙型肝炎患者血清IL-18和IL-1β水平的变化及意义. 世界华人消化杂志 2009; 17(20): 2105-2111

Revised: June 23, 2009

Accepted: June 23, 2009

Published online: July 18, 2009

AIM: To investigate the roles of serum IL-18 and IL-1β in the progression of chronic hepatitis C and explore the correlation between serum IL-18 and IL-1β levels and the efficacy of interferon (IFN) therapy.

METHODS: The levels of IL-18 and IL-1β in the serum of 30 chronic hepatitis C patients were determined before and after they received IFN therapy to observe changes in the serum levels of the two cytokines in different periods after HCV infection. Moreover, the correlations of serum IL-18 and IL-1β levels with ALT level, HCV genotype, IL-2 and IL-6 levels were analyzed. The differences in the serum levels of the two cytokines were also compared between patients with response and nonresponse to interferon treatment. The levels of serum cytokines were determined by ELISA. HCV genotypes were classified by direct sequencing. HCV RNA loads were determined by fluorescence quantitative PCR.

RESULTS: The level of IL-18 in the serum of chronic hepatitis C patients was higher than that of healthy controls (1077.44 ± 657.58 ng/L vs 259.92 ± 328.47 ng/L, P < 0.001). No significant difference in the level of serum IL-1β was noted between chronic hepatitis C patients and healthy controls though it had an upward trend over time (in contrast to a downward trend for IL-18). Severe patients had higher serum IL-1β level than mild ones (4.99 ± 1.44 ng/L vs 3.68 ± 0.76 ng/L, P < 0.05). The levels of the two cytokines were not significantly different among patients with different genotypes or subtypes of HCV. The level of IL-18 was positively correlated with that of IL-2 (r = 0.434, P < 0.05) rather than IL-6. The level of IL-1β was not correlated with those of IL-2 and IL-6. No significant differences were noted in the serum levels of IL-18 and IL-1β between patients with response and nonresponse to IFN therapy.

CONCLUSION: Serum IL-18 and IL-1β levels may be correlated with the chronicity and severity of hepatitis C but can not be used for prediction of the efficacy of IFN therapy.

- Citation: Zhang L, Miao L, Fu HC, Zhao GZ, Feng GH, Dou XG. Significance of changes in serum IL-18 and IL-1β levels in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi 2009; 17(20): 2105-2111

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1009-3079/full/v17/i20/2105.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.11569/wcjd.v17.i20.2105

丙型肝炎病毒(hepatitis C virus, HCV)感染是慢性肝炎的主要病因之一, 急性HCV感染后, 慢性化比例高达80%以上[1-3], 部分患者最终将发展成肝硬化和肝细胞癌[4-6]. 由于HCV具有高度变异性, 目前还没有有效的疫苗问世, 干扰素治疗的持续应答率也仅40%左右[7-8]. 对丙型肝炎慢性化机制的研究以及如何预测及提高干扰素治疗的应答率一直是备受关注的热点. 近年的研究表明, 细胞因子在丙型肝炎的组织损伤、慢性化以及对干扰素治疗的反应中起重要作用[9-11], 在HCV急性感染阶段, Th1细胞分泌的细胞因子占优势, 有利于机体对病毒的清除, 而在慢性阶段则以Th2细胞为主, 而且干扰素治疗过程中Th1细胞优势的维持预示着对治疗有较高的应答率[11-13]. 然而也有报道认为治疗前低Th1/Th2比率预示着对干扰素治疗有较高的持续应答率[14]. IL-1和IL-18主要由抗原提呈细胞(antigen presenting cell, APC)如树突状细胞、巨噬细胞等分泌, 能调节Th1/Th2细胞因子之间的平衡, 与Th1/Th2细胞因子组成细胞因子网络调节系统[15], 共同影响着机体对病毒的清除、组织损伤和慢性化过程. 本研究对30例应用干扰素治疗的慢性丙型肝炎患者血清IL-18和IL-1β进行检测, 探讨慢性丙型肝炎患者血清IL-18和IL-1β水平的变化及与临床和干扰素治疗的关系.

2006-2008年中国医科大学附属盛京医院感染科慢性丙型肝炎住院患者30例, 其中男15例, 女15例, 年龄34-66(平均年龄48.5±8.11)岁. 所有患者均应用干扰素联合利巴韦林治疗, 总疗程为48 wk. 其中8例患者应用Peg-IFN-α-2b(每次50-80 μg, 每周1次), 22例应用IFN-α-2b(每次300 万U, 每周3次), 利巴韦林剂量800-1000 mg/d. 疗效判定: 持续应答组, 治疗结束时ALT正常, HCV RNA阴转, 并持续半年以上; 无应答组, 治疗结束时ALT未恢复正常或HCV RNA持续阳性. 分别留取治疗前和治疗结束时血清, -20℃冻存待测.

1.2.1 细胞因子检测: 血清IL-18、IL-1β、IL-2和IL-6检测采用ELISA法. IL-18试剂盒购自上海森雄科技实业有限公司, IL-1β、IL-2和IL-6试剂盒购自生物晶美工程有限公司. 按试剂盒说明方法进行检测.

1.2.2 HCV基因分型检测: 采用直接测序法, 根据HCV NS5B核苷酸序列进行分型. 引物序列: F1(8351-8378): TGG GGA TCC CGT ATG CCC GCT GCT TTG A; R1(8719-8748): GGC GGA ATT CCT GGT CAT AGC CTC CGT GAA; F2(8379-8402): CTC AAC CGT CAC TGA GAG AGA CAT; R2(8694-8718): GCT CTC AGG CTC GCC GCG TCC TC. 血清中提取HCV RNA, 逆转录成cDNA后, 应用Nested-PCR扩增NS5B基因片段, 片段大小约为340 bp. PCR产物纯化后由沈阳市传染病院中心实验室进行核苷酸序列测定. HCV RNA提取及PCR产物纯化试剂盒购自天星生物制品有限公司. 应用MEGA软件对核苷酸序列进行分析, 确定HCV基因型.

1.2.3 HCV RNA载量检测: 采用特异性荧光探针PCR法, 按试剂盒说明书进行.

1.2.4 血清ALT检测: 由中国医科大学附属盛京医院中心实验室应用美国贝克曼公司生产的8200A全自动生化分析仪常规检测.

统计学处理 应用SPSS15.0软件进行统计学检验, 所用方法包括: 均数的比较、χ2检验和Biraviate相关性检验. P<0.05为显著性差异水平.

30例患者中, 26例有明确的流行病学史, 其中有输血史者15例(50%)、手术史5例(16.7%)、治牙史3例(10%)、纹刺史3例(10%)及原因不清4例(13.3%). 持续应答率46.7%. 应答组和无应答组相比, 年龄、性别、体质量、感染时间及血清HCV RNA载量均无显著差异, 血清ALT水平明显高于无应答组. 应用Peg干扰素者应答率为62.5%, 普通干扰素为40.9%, 两者无显著差异. 基因型分布以1b型最多, 占46.7%, 其余依次为2a型20%、1a型13.3%、2b型10%、3a型6.7%和1c型3.3%. 1b型应答率为35.7%, 2a型为66.7%, 但统计学比较无显著差异(表1).

| 变量 | 应答组 | 无应答组 | P值 |

| n | 14 | 16 | |

| 年龄(岁) | 51.43±9.053 | 45.94±6.403 | 0.063 |

| 男性患者(%) | 50 | 50 | 0.642 |

| 体质量(kg) | 62.96±11.22 | 61.06±12.21 | 0.662 |

| 感染时间(年) | 11.96±9.45 | 15.43±7.17 | 0.298 |

| ALT(U/L) | 124.86±99.42 | 65.44±53.99 | 0.048 |

| HCV RNA载量(lgcp/mL) | 6.32±0.828 | 6.08±0.892 | 0.460 |

| IFN类型(%) | |||

| Peg-α-2b | 62.5 | 37.5 | |

| α-2b | 40.9 | 59.1 | 0.417 |

| HCV基因分型(%) | |||

| 1a型 | 50.0 | 50.0 | |

| 1b型 | 35.7 | 64.3 | 0.336a |

| 1c型 | 0.0 | 100.0 | |

| 2a型 | 66.7 | 33.3 | |

| 2b型 | 33.3 | 66.7 | |

| 3a型 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

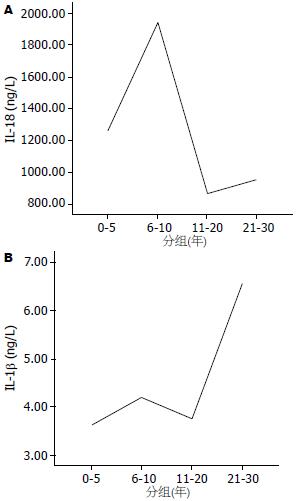

比较慢性丙型肝炎组和健康对照组血清IL-1β和IL-18水平, 结果发现: 慢性丙型肝炎患者血清IL-18水平明显高于健康对照组(1077.44±657.58 ng/L vs 259.92±328.47 ng/L, P<0.001), IL-1β水平(3.88±0.93 ng/L)与健康对照组(3.44±1.36 ng/L)无显著差异(P = 0.209). 根据患者感染时间将其分为0-5年、6-10年、11-20年、21-30年4组, 分别比较4组间细胞因子水平的差异, 结果发现: 血清IL-1β在0-5年组、6-10年组和11-20年组均明显低于21-30年组(3.63±0.42 ng/L, 4.20±0.27 ng/L, 3.76±0.89 ng/L vs 6.56±0.99 ng/L, 均P<0.01). IL-18在6-10年组明显高于11-20年组(1936.50±705.83 ng/L vs 872.35±703.30 ng/L, P = 0.031). 两种细胞因子随着感染时间的变化趋势见图1.

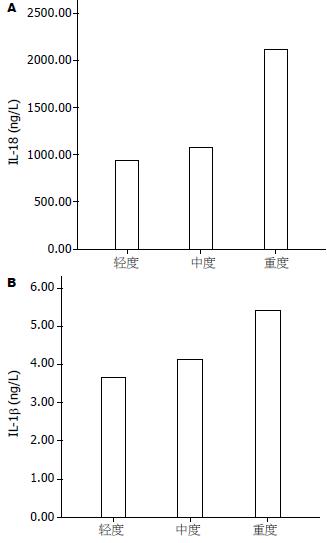

血清IL-1β和IL-18含量与血清ALT水平无明显相关(r = 0.106, 0.325, 均P>0.05), 由轻度到重度2种细胞因子水平均逐渐升高(图1), 但只有重度患者IL-1β含量与轻度相比具有显著性差异(4.99±1.44 ng/L vs 3.68±0.76 ng/L, P<0.05, 图2).

比较不同基因型之间细胞因子水平的差异, 结果发现不同基因型和亚型之间血清IL-1β和IL-18含量均无显著性差异(均P>0.05, 表2).

| 基因型 | n | IL-1β | IL-18 |

| 基因型 | |||

| 1型 | 19 | 4.03±1.04 | 1235.34±751.99 |

| 2型 | 9 | 3.85±0.96 | 933.94±610.16 |

| 3型 | 2 | 3.49±0.09 | 1144.50±692.96 |

| 基因亚型 | |||

| 1a | 4 | 3.76±0.52 | 1242.00±864.06 |

| 1b | 14 | 4.10±1.18 | 1284.92±756.32 |

| 1c | 1 | ||

| 2a | 6 | 3.86±1.16 | 783.67±607.67 |

| 2b | 3 | 3.82±0.53 | 1234.50±602.31 |

血清IL-1β含量与血清IL-2和IL-6水平均无相关(r = 0.098, 0.333, 均P>0.05), IL-18与IL-2呈显著性正相关(r = 0.434, P = 0.017), 与IL-6无相关(r = 0.243, P = 0.196).

比较应答组和无应答组治疗前血清IL-1β和IL-18水平, 两组之间均无显著性差异(表3). 对30例患者中的12例进行了动态观察, 其中应答组5例, 无应答组7例. 治疗结束时应答组和无应答组与治疗前相比, 两种细胞因子水平亦均无显著性差异(表4).

| 细胞因子 | 应答组 | 无应答组 | P值 |

| IL-1β | 3.81±0.88 | 4.05±1.06 | 0.493 |

| IL-18 | 1091.57±610.16 | 1180.25±787.13 | 0.736 |

| 变量 | 治疗前 | 治疗后 | P值 |

| 应答组 | |||

| IL-1β | 3.88±1.48 | 2.84±0.64 | 0.186 |

| IL-18 | 1161.50±578.88 | 1186.10±625.57 | 0.950 |

| 无应答组 | |||

| IL-1β | 3.95±1.04 | 4.46±0.98 | 0.364 |

| IL-18 | 1147.36±738.29 | 740.07±333.84 | 0.208 |

目前认为细胞免疫应答对丙型肝炎患者病情发展及转归起主要作用[16-18]. HCV感染后机体最主要的效应细胞是细胞毒性T淋巴细胞(cytotoxic T lymphocyte, CTL), CTL细胞需在Th细胞辅助下, 才能充分发挥作用, Th细胞通过分泌的细胞因子调节CTL细胞的功能, 并与APC如树突状细胞、巨噬细胞等分泌的IL-1、IL-18等共同组成细胞因子网络调节系统在病毒感染后机体对病毒的清除、组织损伤、病情进展过程中起重要作用.

IL-18主要由激活的单核巨噬细胞产生, 能够促进T细胞增殖, 并使T细胞前体向Th1细胞分化增殖, 在机体的免疫应答反应中起重要作用[19-23]. Falasca et al[24]和Majda-Stanislawska et al[25]研究发现, 慢性丙型肝炎患者血清IL-18水平明显高于正常对照组, 并与肝脏炎症活动和损伤程度呈正相关, 而Schvoerer et al[26]却报道慢性丙型肝炎患者血清和外周血单个核细胞(peripheral blood mononuclear cell, PBMC)内IL-18水平明显低于健康对照组, 并与肝组织炎症活动程度相关. 本研究结果与Falasca et al和Majda-Stanislawska et al的一致, 慢性丙型肝炎患者血清IL-18含量明显高于健康对照组, 且由轻度到重度逐渐升高, 尽管没有达到显著相差异水平, 但与之不同的是, 未发现血清IL-18含量与反映肝脏炎症活动的血清ALT水平有相关性. 进一步比较了HCV感染后0-5年、6-10年、11-20年和21-30年不同感染阶段血清IL-18水平的差异, 发现随着感染时间的延长, IL-18有逐渐下降趋势. 上述结果表明: 血清IL-18水平与丙型肝炎的慢性化和病情轻重有关. 随着感染时间的延长血清IL-18水平逐渐下降, 支持了在HCV感染初期, Th1细胞因子占优势, 随着慢性化的进展, 则出现由Th1细胞向为Th2细胞的优势转化这一观点, 因为IL-18是Th1细胞刺激因子, 可使体外培养的T细胞产生大量的干扰素γ和IL-2[27-28], 本研究对血清IL-18和血清IL-2含量进行相关性分析发现, 二者呈显著性正相关. Schvoerer et al还发现: 感染1b型HCV的慢性丙型肝炎患者血清和PBMC内IL-18水平明显低于其他基因型HCV感染者, 而1b型HCV感染者慢性化比例明显高于其他基因型感染者, 说明IL-18在丙型肝炎的发病机制中可能起一定作用. 本研究比较了不同基因型和亚型之间血清IL-18和IL-1β水平, 未发现有显著性差异. 1b型HCV感染者慢性化比例明显高于其他基因型感染者是否与此有关, 尚需进一步研究.

IL-1β是主要由单核-巨噬细胞和内皮细胞产生, 参与免疫反应、炎症、发热、急性期蛋白质合成等宿主防御反应的一种细胞因子. 有报道IL-1β能增强Th1细胞的优势反应[29], 在丙型肝炎的发病机制起重要作用. 本文对慢性丙型肝炎组和健康对照组血清IL-1β水平比较未发现有显著性差异, 但HCV感染0-5年组、6-10年组和11-20年组血清IL-1β均明显低于21-30组, 轻度患者明显低于重度患者, 上述结果表明, 血清IL-1β水平是可以反映慢性丙型肝炎患者病情轻重和慢性化的指标之一. 未发现血清IL-1β含量与Th1类细胞因子IL-2和Th2类细胞因子IL-6含量相关, 是否与其他Th1/Th2细胞因子有关, 有待于进一步研究. 与本研究结果不同, Lapiński et al[30]研究发现, 慢性丙型肝炎患者血清IL-1β水平明显高于正常对照组, 并与肝组织内IL-1β水平升高相一致, 与肝脏组织学炎症和纤维化程度不相关. 因此, 有关IL-1β在慢性丙型肝炎发病机制中的作用及与Th1/Th2细胞因子之间的相互关系, 尚需进一步研究已证实.

所观察的30例患者中, 26例有明确的流行病学史, 主要感染原因依次为输血、手术、治牙及纹刺, 呼吁应加强此方面的宣传及管理, 以降低丙型肝炎的发病率. 干扰素治疗的持续应答率为46.7%, 应用Peg干扰素者(62.5%)高于普通干扰素(40.9%), 但统计学检测无显著性差异. 最近有报道应用Peg干扰素治疗慢性丙型肝炎的持续应答率高达80%以上[31-32], 但治疗费用过高仍是阻碍部分患者选择Peg干扰素的主要原因. 应答组和无应答组相比, 年龄、性别、体质量、感染时间及血清HCV RNA载量均无显著差异, 血清ALT水平明显高于无应答组, 表明肝脏存在炎症活动时进行干扰素抗病毒治疗效果较好, 这与以往的研究结论一致. 基因型分布以1b型(46.7%)和2a型(20%)为主, 尚有1a、1c、2b和3a型存在. 2a型患者对干扰素治疗的应答率(66.7%)高于1b型(35.7%), 但可能由于病例数较少, 统计学检测并无显著性差异. 分析血清IL-18和IL-1β含量与干扰素疗效的关系发现, 应答组和无应答组干扰素治疗前2种细胞因子水平无显著性差异, 对其中12例患者进行了动态观察(应答组5例, 无应答组7例), 治疗结束时应答组和无应答组与治疗前相比, 2种细胞因子水平亦均无显著性差异. Tian et al[33]报道血清和肝脏中IL-1β能降低IFN-α的信号传导, 是慢性丙型肝炎干扰素治疗抵抗的机制之一, 本文的研究结果也发现干扰素治疗无应答组血清IL-1β含量高于应答组, 干扰素治疗应答组治疗结束时血清IL-1β含量有所下降, 无应答组则升高, 但统计学检测未达到显著差异水平. Mihm et al[34]报道在感染HCV-1型的丙型肝炎患者中, 应答者干扰素治疗前血清IL-18水平低于无应答者, 提示治疗前血清低水平IL-18与干扰素持续应答呈正相关.

可见, 目前对IL-1β和IL-8在慢性丙型肝炎发病机制、病情进展及干扰素治疗过程中作用的研究还缺乏系统性, 研究结果也不完全相同, 仍需要进行进一步的研究. 对细胞因子多态性与丙型肝炎发病机制及IFN-α治疗反应之间的关系的深入研究, 将为干扰素治疗无应答者能否联合免疫调节治疗以提高应答率提供理论依据.

研究表明, Th1/Th2相关细胞因子在丙型肝炎发病机制和干扰素治疗效果中起重要作用. IL-18和IL-1β主要由抗原递呈细胞分泌, 能调节Th1/Th2细胞因子之间的平衡, 与Th1/Th2细胞因子共同影响着机体对病毒的清除、组织损伤和慢性化过程. 虽然目前此方面的研究较多, 但所得的结论却不尽相同.

高泽立, 主任医师, 上海交通大学医学院附属第九人民医院周浦分院消化科

干扰素治疗应答率低仍是目前慢性丙型肝炎治疗的瓶颈, 纠正细胞因子失衡亦即免疫调节治疗能否提高干扰素治疗应答率将是今后慢性丙型肝炎抗病毒治疗的一个新方向.

有研究报道慢性丙型肝炎患者血清IL-18水平明显高于正常对照组, 并与肝脏炎症活动和损伤程度呈正相关, 治疗前血清低水平IL-18与干扰素持续应答呈正相关. 慢性丙型肝炎患者血清IL-1β水平明显高于正常对照组, 但与肝脏组织学炎症和纤维化程度不相关. 血清和肝脏中IL-1β能降低IFN-α的信号传导, 是慢性丙型肝炎干扰素治疗抵抗的机制之一.

本文比较系统地研究了慢性丙型肝炎患者血清IL-18和IL-1β水平与丙型肝炎慢性化、病情轻重、肝脏炎症活动以及干扰素疗效的关系, 同时分析了二者与Th1细胞因子IL-2和Th2细胞因子IL-6之间的相关性.

血清IL-18和IL-1β水平分别与丙型肝炎的慢性化和病情轻重相关, 该两种细胞因子水平与干扰素疗效无关, 不能对疗效进行预测.

本文选题密切联系临床, 参考文献较新颖, 值得临床医生阅读.

编辑: 李军亮 电编:何基才

| 1. | Alter MJ, Margolis HS, Krawczynski K, Judson FN, Mares A, Alexander WJ, Hu PY, Miller JK, Gerber MA, Sampliner RE. The natural history of community-acquired hepatitis C in the United States. The Sentinel Counties Chronic non-A, non-B Hepatitis Study Team. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1899-1905. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Di Bisceglie AM, Goodman ZD, Ishak KG, Hoofnagle JH, Melpolder JJ, Alter HJ. Long-term clinical and histopathological follow-up of chronic posttransfusion hepatitis. Hepatology. 1991;14:969-974. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 3. | Seeff LB. Natural history of viral hepatitis, type C. Semin Gastrointest Dis. 1995;6:20-27. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Gane EJ. The natural history of recurrent hepatitis C and what influences this. Liver Transpl. 2008;14 Suppl 2:S36-S44. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Masuzaki R, Tateishi R, Yoshida H, Yoshida H, Sato S, Kato N, Kanai F, Sugioka Y, Ikeda H, Shiina S. Risk assessment of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis C patients by transient elastography. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:839-843. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 6. | Kwon JH, Bae SH. [Current status and clinical course of hepatitis C virus in Korea]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2008;51:360-367. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Trepo C. Genotype and viral load as prognostic indicators in the treatment of hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat. 2000;7:250-257. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 8. | Kogure T, Ueno Y, Fukushima K, Nagasaki F, Kondo Y, Inoue J, Matsuda Y, Kakazu E, Yamamoto T, Onodera H. Pegylated interferon plus ribavirin for genotype Ib chronic hepatitis C in Japan. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:7225-7230. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 9. | Priĭmiagi LS, Tefanova VT, Tallo TG, Shmidt EV, Solomonova OV, Tuĭsk TP. [Immune-regulating Th1- and Th2-cytokines in chronic infections caused by hepatitis B and C viruses]. Vopr Virusol. 2003;48:37-40. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Lapiński TW, Dabrowska MM. [Activity of cytokines in chronic HCV-infected patients]. Przegl Epidemiol. 2007;61:747-754. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Falasca K, Mancino P, Ucciferri C, Dalessandro M, Zingariello P, Lattanzio FM, Petrarca C, Martinotti S, Pizzigallo E, Conti P. Inflammatory cytokines and S-100b protein in patients with hepatitis C infection and cryoglobulinemias. Clin Invest Med. 2007;30:E167-E176. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Sobchak DM, Korochkina OV. [Cytokine regulation of immune response in patients with acute HCV-infection]. Ter Arkh. 2005;77:23-29. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Trapero M, García-Buey L, Muñoz C, Vitón M, Moreno-Monteagudo JA, Borque MJ, Quintana NE, Moreno-Otero R. Maintenance of T1 response as induced during PEG-IFNalpha plus ribavirin therapy controls viral replication in genotype-1 patients with chronic hepatitis C. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2005;97:481-490. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Masaki N, Fukushima S, Hayashi S. Lower th-1/th-2 ratio before interferon therapy may favor long-term virological responses in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:2163-2169. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 15. | Fan Z, Huang XL, Kalinski P, Young S, Rinaldo CR Jr. Dendritic cell function during chronic hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2007;14:1127-1137. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 16. | Hiroishi K, Ito T, Imawari M. Immune responses in hepatitis C virus infection and mechanisms of hepatitis C virus persistence. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1473-1482. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 17. | Satake S, Nagaki M, Kimura K, Naiki T, Hayashi H, Sugihara J, Tomita E, Moriwaki H. Significant effect of hepatitis C virus specific CTLs on viral clearance in patients with type C chronic hepatitis treated with antiviral agents. Hepatol Res. 2008;38:491-500. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 18. | Abbas Z, Moatter T, Hussainy A, Jafri W. Effect of cytokine gene polymorphism on histological activity index, viral load and response to treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis C genotype 3. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:6656-6661. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Dinarello CA, Novick D, Puren AJ, Fantuzzi G, Shapiro L, Mühl H, Yoon DY, Reznikov LL, Kim SH, Rubinstein M. Overview of interleukin-18: more than an interferon-gamma inducing factor. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;63:658-664. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Akira S. The role of IL-18 in innate immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2000;12:59-63. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 21. | Sugawara I. Interleukin-18 (IL-18) and infectious diseases, with special emphasis on diseases induced by intracellular pathogens. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:1257-1263. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 22. | Takaki A, Wiese M, Maertens G, Depla E, Seifert U, Liebetrau A, Miller JL, Manns MP, Rehermann B. Cellular immune responses persist and humoral responses decrease two decades after recovery from a single-source outbreak of hepatitis C. Nat Med. 2000;6:578-582. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 23. | Frucht DM, Fukao T, Bogdan C, Schindler H, O'Shea JJ, Koyasu S. IFN-gamma production by antigen-presenting cells: mechanisms emerge. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:556-560. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 24. | Falasca K, Ucciferri C, Dalessandro M, Zingariello P, Mancino P, Petrarca C, Pizzigallo E, Conti P, Vecchiet J. Cytokine patterns correlate with liver damage in patients with chronic hepatitis B and C. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2006;36:144-150. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Majda-Stanislawska E, Pietrzak A, Brzezińska-Błaszczyk E. Serum IL-18 concentration does not depend on the presence of HCV-RNA in serum or in PBMC. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:212-215. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Schvoerer E, Navas MC, Thumann C, Fuchs A, Meyer N, Habersetzer F, Stoll-Keller F. Production of interleukin-18 and interleukin-12 in patients suffering from chronic hepatitis C virus infection before antiviral therapy. J Med Virol. 2003;70:588-593. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 27. | Matsumoto S, Tsuji-Takayama K, Aizawa Y, Koide K, Takeuchi M, Ohta T, Kurimoto M. Interleukin-18 activates NF-kappaB in murine T helper type 1 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;234:454-457. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 28. | Kimura K, Kakimi K, Wieland S, Guidotti LG, Chisari FV. Interleukin-18 inhibits hepatitis B virus replication in the livers of transgenic mice. J Virol. 2002;76:10702-10707. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 29. | McGuinness PH, Painter D, Davies S, McCaughan GW. Increases in intrahepatic CD68 positive cells, MAC387 positive cells, and proinflammatory cytokines (particularly interleukin 18) in chronic hepatitis C infection. Gut. 2000;46:260-269. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 30. | Lapiński TW. The levels of IL-1beta, IL-4 and IL-6 in the serum and the liver tissue of chronic HCV-infected patients. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 2001;49:311-316. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Jeong S, Kawakami Y, Kitamoto M, Ishihara H, Tsuji K, Aimitsu S, Kawakami H, Uka K, Takaki S, Kodama H. Prospective study of short-term peginterferon-alpha-2a monotherapy in patients who had a virological response at 2 weeks after initiation of interferon therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:541-545. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 32. | Hadziyannis SJ, Sette H Jr, Morgan TR, Balan V, Diago M, Marcellin P, Ramadori G, Bodenheimer H Jr, Bernstein D, Rizzetto M, Zeuzem S, Pockros PJ, Lin A, Ackrill AM. Peginterferon-alpha2a and ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C: a randomized study of treatment duration and ribavirin dose. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:346-355. [PubMed] |