修回日期: 2005-09-29

接受日期: 2005-09-30

在线出版日期: 2006-01-18

目的: 探讨组织金属蛋白酶抑制因子-3 (tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 3, TIMP3)基因启动子甲基化与其蛋白表达的相关性,并分析TIMP3基因CpG岛异常甲基化与胃腺癌及其临床病理特征的关联性.

方法: 应用甲基化特异性PCR(MSP)技术和免疫组织化学方法分别检测78例患者的胃正常黏膜组织、胃癌组织及转移淋巴结中, TIMP3基因启动子甲基化和蛋白表达情况.

结果: 胃正常黏膜组织、早期、进展期胃癌组织和转移淋巴结中TIMP3基因启动子均有甲基化修饰, 其阳性率分别为35.9%(28/78); 85.0%(17/20), 89.7%(52/58); 转移淋巴结100%(78/78). 胃癌组TIMP3基因启动子甲基化率明显高于胃正常黏膜组(P<0.05).胃正常黏膜组织TIMP3蛋白表达全部为阳性(100%), 20例早期胃癌中, 6例阳性(30%), 58例进展期胃癌中, 2例阳性(3.4%), 在转移淋巴结中全部不表达(0%). 胃癌70例蛋白表达阴性的标本中, 64例TIMP3基因启动子甲基化阳性(91.4%), TIMP3蛋白表达与启动子甲基化呈明显负相关(P<0.01).

结论: 启动子区CpG岛高甲基化是胃癌组织中TIMP3基因表达失活的主要机制,可能成为胃癌分子诊断与病期评估的标志之一.

引文著录: 关志宇, 戴冬秋. 胃癌 TIMP3 基因启动子甲基化及其蛋白表达的研究. 世界华人消化杂志 2006; 14(2): 138-143

Revised: September 29, 2005

Accepted: September 30, 2005

Published online: January 18, 2006

AIM: To analyze the relations among the aberrant methylation of the promoter CpG islands of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 3 (TIMP3) gene, its protein expression, and the clinicopathological features of gastric adenocarcinoma.

METHODS: The methylation status of promoter CpG islands and protein expression of TIMP3 gene in the tumors and the adjacent normal mucosal tissues of 78 patients with gastric adenocarcinoma were detected by methylation-specific PCR (MSP) and immunohistochemistry respectively.

RESULTS: The CpG island methylation of TIMP3 was detected in tumour tissues, cancer-adjacent tissues and lymph node with metastasis. In increasing order of frequency, the hypermethylation rates of these tissues were 35.9% (28 of 78 non-neoplastic tissues), 85% (17 of 20 early-stage cases), 89.7% (52 of 58 progression-stage cases), and 100% (78 of 78 metabasis lymph node), respectively, and there was marked difference between cancerous and non-cancerous tissues (P < 0.05). However, there were no significant differences among subgroups of tumor tissues (P > 0.05). Immunohistochemistry analysis confirmed TIMP3 down-regulation in tumur tissues. The rate of TIMP3 gene expression in non-neoplastic tissues was 100%, while in tumour tissues, it decreased dramatically: in early-stage cancer, it decreased to 30% (6/20); in progression stage, it was 3.4% (2/58); and in metabasis lymph node, it was 0% (0/78). Of 70 tumor tissues with negative TIMP3 expression, 64 (91.4%) were hypermethylated and 6 (8.6%) were unmethylated, indicating that there were significant association between hypermethylation and reduced or negative TIMP3 expression (P < 0.01).

CONCLUSION: The hypermethylation of promoter region in CpG islands is a main mechanism of reduced and loss expression of TIMP3 gene, and it may provide an evidence for molecular diagnosis and stage evaluation of gastric cancer.

- Citation: Zhi-Yu G, Dong-Qiu D. Promoter methylation and expression of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 3 gene in gastric cancer. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi 2006; 14(2): 138-143

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1009-3079/full/v14/i2/138.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.11569/wcjd.v14.i2.138

胃癌(gastric carcinoma)是全世界最常见的恶性肿瘤之一, 其发生发展是一个多基因参与的多阶段过程. 这些因素最终在不同阶段作用于不同基因, 引起相关基因的结构及表达水平改变, 导致胃癌的发生发展. 抑癌基因功能的丢失可能通过多种途径, 目前普遍认为DNA异常甲基化改变是除缺失与突变之外导致抑癌基因表达失活的第3种机制[1,2].在肿瘤的发生发展中起着不可忽视的作用. 管家基因上游启动子区含有丰富的CpG序列, 称为CpG岛, 通常情况下, 这些部位的胞嘧啶不发生甲基化, 但在一些因素的刺激下发生甲基化而使其表达受到抑制[3]. 目前发现很多肿瘤相关基因的失活都与其启动子区的甲基化有关, 如p16, THBS1, TIMP3, hMLH1, MGMT等[4-8]. 组织金属蛋白酶抑制因子-3(tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-3, TIMP3)拮抗基质金属蛋白酶的活性, 抑制肿瘤的生长、血管形成、浸润和转移, TIMP3的失活与肿瘤的发生有关[9]. 我们应用甲基化特异性PCR(methylation-specfic PCR, MSP)技术和免疫组织化学方法分别检测78例胃癌患者的胃正常黏膜组织、胃癌组织和转移淋巴结中TIMP3基因启动子CpG岛甲基化和蛋白表达情况, 探讨其基因启动子甲基化与其蛋白表达的相关性, 并分析TIMP3基因CpG岛异常甲基化与胃腺癌及其临床病理特征的关联性.

1998-03/2005-05中国医科大学附属第一医院及辽宁省肿瘤医院胃癌患者术后胃正常组织、胃癌组织和转移淋巴结78例, 经病理确定诊断, 按国际抗癌联盟新TNM分期标准、中国医科大学肿瘤研究所胃癌生长方式分型及日本胃癌处理规约分期、分型[10-12]. 男54例, 女24例,平均年龄56.2±7.5岁,早期胃癌20例, 进展期胃癌58例; 分化型44例, 未分化型14例. 10 mmol/L hydroquinone和3.9 mol/L sodium bisulfite购自Sigma公司; DNA Clean-up System购自Promega公司; TIMP3抗体及SP试剂盒购自大连博士德生物工程有限公司.

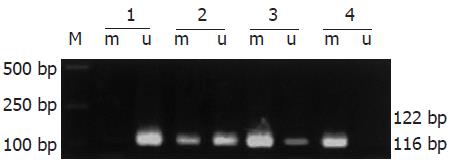

1.2.1 甲基化特异性PCR(MSP): 采用甲基化特异性PCR方法[13],甲基化酶处理的和未处理的正常人的外周血细胞分别为阳性和阴性对照. 甲基化(TIMP3-M)和非甲基化(TIMP3-U)引物, TIMP3-M引物序列为: 5, CGTTTCGTTATTTTTTGTTTTTCGGTTTTC-3,和5,-CCGAAAACCCCGCCTCG-3,; TIMP3 -U引物序列为: 5,-TTTTGTTTTGTTATTTTTTGTTTTTGGTTTT-3,和5,-CCCCCCAAAAACCCCACCTCA-3,. 反应条件: 95℃预变性5 min后, 95℃变性30 s, 59℃退火60 s, 72℃延伸60 s, 40个循环, 72℃再延伸10 min, 琼脂糖凝胶电泳, EB染色. 结果经激光密度扫描仪(Pharmacia LKB Ul troscan)采集数据, 分析电泳结果. 实验重复三次, 取其平均值进行统计分析.

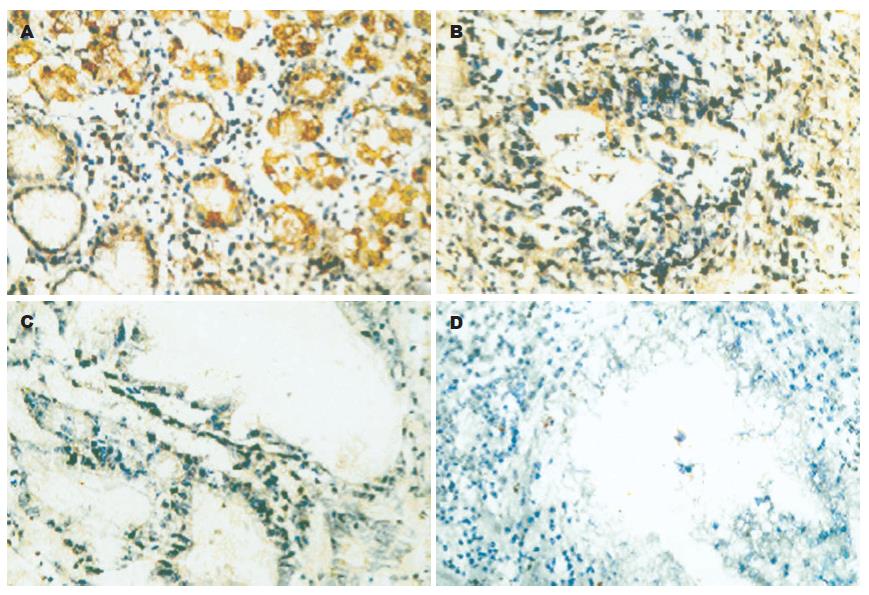

1.2.2 用免疫组织化学: 采用链霉菌抗生素蛋白经过氧化酶染色法, 免疫组化染色步骤按说明书进行. 判定标准: 染色后细胞质呈棕黄色为阳性, 以正常组织染色区域为阳性对照, 以PBS代替一抗的正常切片为阴性对照. 积分标准参照Shimizu et al[14]法: 高倍镜下观察染色强度和阳性细胞分布范围分别积分, 无染色者为0分, 染色弱但明显强于阴性对照者为1分, 染色清晰者为2分, 染色强者为3分; 无阳性细胞者为0分, 阳性细胞数<30%者为1分, 30%-60%者为2分, >60%者为3分, 按积分之和进行评定. ≤2分为TIMP3表达阴性, 3分为弱阳性,4-5分为阳性, 6分为强阳性.

统计学处理 以χ2及Fisher精确检验分析不同研究对象间TIMP3基因启动子甲基化率和蛋白表达的差异. 采用SPSS12统计软件包分析.

以研究对象基因组DNA为模板, 经MSP扩增后, 其甲基化和非甲基化扩增产物分别为116 bp和122 bp. 胃正常组织、胃癌组织和转移淋巴结中TIMP3基因启动子均存在甲基化修饰现象, 其检出的阳性率分别为: 早期胃癌85%(17/20)、进展期胃癌89.7%(52/58)及转移淋巴结98.7%(77/78), 而胃正常组织则仅为35.9%(28/78), 经统计学检验, 胃癌各组与胃正常组织比较均有非常显著的意义(P<0.01, 图1, 表1), 提示胃癌及转移淋巴结组织中, TIMP3甲基化率升高, 该基因甲基化可能参与胃癌的发生和转移.

| 组织 | n | TIMP3启动子甲基化阳性 | TIMP3蛋白表达阳性 |

| 正常胃 | 78 | 28 (35.9) | 78 (100.0) |

| 早期胃癌 | 20 | 17 (85.0) | 9 (45.0) |

| 进展期胃癌 | 58 | 52 (89.7) | 21(36.2) |

| 转移淋巴结 | 78 | 77 (98.7) | 12 (15.4) |

78例胃正常组织TIMP3蛋白表达全部为阳性(100%), 胃癌组织中, 20例早期胃癌中9例阳性, 11例阴性(55%); 58例进展期胃癌中21例阳性, 37例阴性(63.8%), 78例转移淋巴结中阳性12, 阴性66(84.6%), 经统计学检验, 胃癌各组与胃正常组织比较均有非常显著的意义(P<0.01, 图2, 表1), 提示胃癌及转移淋巴结组织中, TIMP3蛋白表达率降低, 该基因蛋白表达可能由于TIMP3甲基化导致蛋白表达下降. 正常腺体TIMP3蛋白表达主要位于细胞质, 个别细胞可见细胞膜有少量表达(图2A), 腺体结构无破坏, 着色没有明显减弱; 早期胃癌腺体结构破坏, 癌细胞着色很弱; 进展期胃癌癌组织呈大的实性片块状生长(未分化癌), 除个别细胞着色外其余均不着色.

恶性肿瘤为多因素、多阶段形成, 其生物学特性表现为浸润生长和转移, 其发生机制在于细胞内部基因结构和功能发生了异常改变. 现代肿瘤理论认为, 在肿瘤的形成过程中包含两大类机制, 一个是遗传学层面, 即通过DNA核苷酸序列改变而形成突变; 另一个就是表遗传学(epigenetics)层面, 其研究的对象是基因表达的变化, 这种变化可通过减数分裂遗传, 但不涉及有关基因DNA序列的改变, 通过DNA自身化学修饰方式从转录水平影响基因的表达, 调控DNA功能, 此机制在肿瘤的形成过程中越来越受到重视[15,16]. 肿瘤组织DNA常常发生其启动子区域的异常甲基化, 包括与细胞增殖周期密切相关的癌基因低甲基化和抑癌基因高甲基化改变, 这些异常甲基化改变一方面可激活癌基因[17-19], 另一方面可使抑癌基因由于5,端启动子调控区CpG岛异常高甲基化而抑制mRNA转录作用[20], 导致该基因的失活. TIMPs家族有4个成员(TIMP1, 2, 3, 4), 其中TIMP1, 2, 4为可溶性分泌蛋白, TIMP3是与细胞外基质(ECM)结合的非可溶性蛋白, 位于细胞外膜上[21], 并能紧密连结基底膜, 抑制TNF-α转换酶而通过稳定细胞膜表面TNF-α受体诱导程序性死亡[22], 其诱导细胞凋亡功能依赖两条途径: 依赖MMP和非依赖MMP途径. TIMP3, 4虽然与MMP-2有高度亲和力, 却能有效抑制MT1-MMP激活MMP-2酶原的过程, 以抑制肿瘤细胞的生长及转移. Smith et al[23]发现表达TIMP3的人结肠癌细胞株处于有丝分裂期的极少, 均被阻滞于G1期, 但当存在肿瘤坏死因子α(TNF-α)抗体时作用下降70%.

为探讨抑癌基因TIMP3与胃癌的关系及其在胃癌中的灭活机制, 我们检测了正常胃黏膜组织、胃癌组织及转移淋巴结中TIMP3基因5,端CpG岛异常甲基化的情况. 结果发现, 85%以上的各期胃癌有TIMP3基因5,端CpG岛异常甲基化现象,与正常胃组织相比有显著性差异(P<0.01), 证明TIMP3基因启动子CpG岛甲基化是该基因表达缺失的主要原因, 也是其在胃癌中的主要灭活机制. Gagnon et al[24]报道在所有TIMP3 mRNA表达缺失、TIMP3基因的启动子CpG岛均为甲基化的MCF-7肺癌细胞株中, 应用5-AZA-CdR诱导TIMP3基因去甲基化后, 进行诱导前后的RT-PCR检测, 发现TIMP3基因重新表达, 与本研究结果相同. 本结果提示, 78例正常胃组织中TIMP3蛋白全部表达阳性, 而甲基化阳性表达为28例(35.9%); 20例早期胃癌中TIMP3蛋白表达9例阳性, 甲基化阳性表达为17例(85%); 58例进展期胃癌中TIMP3蛋白表达21例阳性, 甲基化阳性表达为52例(89.7%); 78例转移淋巴结中TIMP3蛋白表达阳性12, 甲基化阳性表达为77例(98.7%), 早期癌、进展期癌和转移淋巴结与正常组织甲基化率的差异均有显著性(P<0.01), 证实了TIMP3蛋白表达缺失与该基因启动子CpG岛甲基化密切相关. Feng et al[25]报道在对绒毛膜癌细胞系JAR和JEG-3研究中有相同结果, 证明TIMP3基因启动子CpG岛甲基化是该基因蛋白表达缺失的主要原因. 在进展期胃癌标本中, 52例TIMP3启动子CpG岛发生甲基化, 蛋白表达21例, 提示除启动子CpG岛甲基化以外, 一些其他的因素如基因变异, 也可引起该基因表达缺失. 在本实验中出现第34号标本甲基化和未甲基化均为阳性, 通常解释为: 该基因可能存在不完全甲基化状况; 肿瘤组织中混杂的非肿瘤细胞, 经MSP(用未甲基化引物)扩增后, 也可有阳性产物. 该标本TIMP3蛋白表达为阴性, 因此, 此标本应该定义为甲基化阳性. Kerbel[26]报道, 具有转移潜能的亚克隆瘤细胞在原发癌灶发生的早期即具有生长优势, 这种生长优势是由于转移性亚克隆细胞群体可分泌某种特殊因子或对局部细胞生长因子具有特殊反应而呈现的选择性生长所致. 所以, 检测原发肿瘤标本中某些肿瘤分子标志的水平有可能反应出整个肿瘤的一般转移特性. 本组的胃正常组织仅为35.9%,早期癌和进展期癌的甲基化率升高(85%和89.7%), 淋巴结的甲基化率为98.7%; 均匀一致的TIMP3蛋白强阳性表达仅存在于胃正常组织, 而早期、进展期胃癌仅见局灶性弱阳性表达, 转移淋巴结几乎没有阳性表达. 上述结果提示TIMP3发生甲基化随着肿瘤的进展逐步升高, 其蛋白表达逐渐下降, 具有转移潜能而在生长中逐渐占据优势并发生转移. Yegnasubramanian et al[27]报道, 使用real-time MSP对前列腺癌细胞系、73例早期前列腺癌、91例转移前列腺癌和25例前列腺非癌组织进行研究发现, 肿瘤的转移与TIMP3甲基化的表达相关, 并因此推测CpG甲基化与前列腺癌的分级和进展有关, 这一事实提示TIMP3基因甲基化在转移过程中起着重要作用. 据此, 作者认为, TIMP3 CpG甲基化的检测在预测原发肿瘤的转移潜能方面具有一定的实用价值.

TIMP3在人的众多类型的恶性肿瘤中有高频率的变异, 包括突变、缺失、甲基化、染色体易位等[28], 这些变异导致该基因的正常抑制细胞增殖的功能丧失(即灭活或失活), 并与癌的发生发展密切相关[29]. 但TIMP3基因在原发性胃癌中的变异情况却报道较少, 并且缺失率较低, 没有发现突变的存在, 提示可能TIMP3基因在胃癌组织中有其他的失活机制[30]. 由此可见, 肿瘤发病机制的复杂性已不仅体现在由基因突变或缺失导致的遗传改变, 还表现在以DNA甲基化为代表的表遗传学改变, 深入研究DNA甲基化与基因表达的关系及作用机制将有利于肿瘤发病机制的研究及指导临床治疗.

虽然目前已经发现了一些肿瘤抑制基因的改变, 但是癌发展的分子机制还不是很清楚. 异常CpG岛甲基化在各种肿瘤中都可以被发现, 并与基因的失活存在密切关系.

表遗传学研究的对象是基因表达的变化, 这种变化可通过减数分裂遗传, 但不涉及有关基因DNA序列的改变, 通过DNA自身化学修饰方式从转录水平影响基因的表达, 调控DNA功能, 此机制在肿瘤的形成过程中越来越受到重视.

DNA甲基化是当今肿瘤研究的热点, 其中许多内在机制尚待深入研究. 本研究是肿瘤抑制基因在胃癌组织及其癌旁组织的甲基化表达水平的对比研究, 揭示其甲基化与胃癌生物学行为的关系.

本文研究了DNA甲基化与基因表达的关系及作用机制, 有利于肿瘤发病机制的研究及指导临床治疗.

本项研究立题新颖, 指标先进, 方法切实可行, 有一定先进性和科学性, 并且能够结合中国医科大学附属第一医院多年胃癌研究和临床工作的优势进行研究, 也有实际意义.

编辑: 潘伯荣 审读: 张海宁 电编: 李琪

| 1. | Fang JY, Lu YY. Effects of histone acetylation and DNA methylation on p21( WAF1) regulation. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:400-405. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Wajed SA, Laird PW, DeMeester TR. DNA methylation: an alternative pathway to cancer. Ann Surg. 2001;234:10-20. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Kimura N, Nagasaka T, Murakami J, Sasamoto H, Murakami M, Tanaka N, Matsubara N. Methylation profiles of genes utilizing newly developed CpG island methylation microarray on colorectal cancer patients. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e46. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Kang GH, Lee HJ, Hwang KS, Lee S, Kim JH, Kim JS. Aberrant CpG island hypermethylation of chro-nic gastritis, in relation to aging, gender, intestinal metaplasia, and chronic inflammation. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:1551-1556. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Oue N, Matsumura S, Nakayama H, Kitadai Y, Taniyama K, Matsusaki K, Yasui W. Reduced expression of the TSP1 gene and its association with promoter hypermethylation in gastric carcinoma. Oncology. 2003;64:423-429. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Xue WC, Chan KY, Feng HC, Chiu PM, Ngan HY, Tsao SW, Cheung AN. Promoter hypermethylation of multiple genes in hydatidiform mole and choriocarcinoma. J Mol Diagn. 2004;6:326-334. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Kim H, Kim YH, Kim SE, Kim NG, Noh SH, Kim H. Concerted promoter hypermethylation of hMLH1, p16INK4A, and E-cadherin in gastric carcinomas with microsatellite instability. J Pathol. 2003;200:23-31. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Lindsey JC, Lusher ME, Anderton JA, Bailey S, Gilbertson RJ, Pearson AD, Ellison DW, Clifford SC. Identification of tumour-specific epigenetic events in medulloblastoma development by hypermethylation profiling. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:661-668. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Sobin LH, Fleming ID. TNM classification of malignant tumors, fifth edition (1997). Union Internationale Contre le Cancer and the American Joint Committee on Cancer. Cancer. 1997;80:1803-1804. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Zhang WF, Chen JQ, Shan JX, Wang ZS, Qi CL, Chen ZH, Wang SB, Liang HW. Indication of radical surgery (R2, R3) based upon the pattern of lymph node metastasis from gastric cancer. Zhonghua Zhongliu Zazhi. 1987;9:286-289. [PubMed] |

| 11. | 日本胃癌学会. 胃癌取扱ぃ规约. 第13版. 东京: 金原出版. 1993;8. |

| 12. | Herman JG, Graff JR, Myohanen S, Nelkin BD, Baylin SB. Methylation-specific PCR: a novel PCR assay for methylation status of CpG islands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9821-9826. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Shimizu M, Saitoh Y, Itoh H. Immunohistochemical staining of Ha-ras oncogene product in normal, benign, and malignant human pancreatic tissues. Hum Pathol. 1990;21:607-612. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Vogelauer M, Wu J, Suka N, Grunstein M. Global histone acetylation and deacetylation in yeast. Nature. 2000;408:495-498. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Wajed SA, Laird PW, DeMeester TR. DNA methylation: an alternative pathway to cancer. Ann Surg. 2001;234:10-20. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Suter CM, Norrie M, Ku SL, Cheong KF, Tomlinson I, Ward RL. CpG island methylation is a common finding in colorectal cancer cell lines. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:413-419. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Baylin SB, Herman JG. DNA hypermethylation in tumorigenesis: epigenetics joins genetics. Trends Genet. 2000;16:168-174. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Colot V, Maloisel L, Rossignol JL. DNA repeats and homologous recombination: a probable role for DNA methylation in genome stability of eukaryotic cells. J Soc Biol. 1999;193:29-34. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Kaneda A, Kaminishi M, Yanagihara K, Sugimura T, Ushijima T. Identification of silencing of nine genes in human gastric cancers. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6645-6650. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Leco KJ, Waterhouse P, Sanchez OH, Gowing KL, Poole AR, Wakeham A, Mak TW, Khokha R. Spontaneous air space enlargement in the lungs of mice lacking tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-3 (TIMP-3). J Clin Invest. 2001;108:817-829. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Mannello F, Gazzanelli G. Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases and programmed cell death: conundrums, controversies and potential implications. Apoptosis. 2001;6:479-482. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Smith MR, Kung H, Durum SK, Colburn NH, Sun Y. TIMP-3 induces cell death by stabilizing TNF-alpha receptors on the surface of human colon carcinoma cells. Cytokine. 1997;9:770-780. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Gagnon J, Shaker S, Primeau M, Hurtubise A, Momparler RL. Interaction of 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine and depsipeptide on antineoplastic activity and activation of 14-3-3sigma, E-cadherin and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 3 expression in human breast carcinoma cells. Anticancer Drugs. 2003;14:193-202. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Feng H, Cheung AN, Xue WC, Wang Y, Wang X, Fu S, Wang Q, Ngan HY, Tsao SW. Down-regulation and promoter methylation of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 3 in choriocarcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;94:375-382. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Kerbel RS. Growth dominance of the metastatic cancer cell: cellular and molecular aspects. Adv Cancer Res. 1990;55:87-132. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Yegnasubramanian S, Kowalski J, Gonzalgo ML, Zahurak M, Piantadosi S, Walsh PC, Bova GS, De Marzo AM, Isaacs WB, Nelson WG. Hypermethylation of CpG islands in primary and metastatic human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1975-1986. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Lee S, Lee HJ, Kim JH, Lee HS, Jang JJ, Kang GH. Aberrant CpG island hypermethylation along multistep hepatocarcinogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:1371-1378. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Galm O, Rountree MR, Bachman KE, Jair KW, Baylin SB, Herman JG. Enzymatic regional methylation assay: a novel method to quantify regional CpG methylation density. Genome Res. 2002;12:153-157. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Kang GH, Lee S, Shim YH, Kim JC, Ro JY. Profile of methylated CpG sites of hMLH1 promoter in primary gastric carcinoma with microsatellite instability. Pathol Int. 2002;52:764-768. [PubMed] |