修回日期: 2003-12-09

接受日期: 2004-01-08

在线出版日期: 2004-05-15

目的: 分析外源质粒pcDNA3s经胃肠道吸收后在组织中的动态变化, 评价外源质粒整合到宿主基因组上的可能性.

方法: 分别于灌胃200 mg质粒 pcDNA3s后1, 3, 6, 24, 48 h及3, 6 wk, 提取小鼠肺、肾、脾、肠系膜淋巴结、胸腺、生殖器官、粪便、十二指肠、大肠、血液及肝脏的总DNA, 通过PCR方法检测质粒pcDNA3s在各组织中的分布及随时间变化的情况. 琼脂糖凝胶分离高分子量基因组DNA与游离质粒, PCR方法检测外源质粒在基因组DNA上的整合情况.

结果: 灌胃给药后1 h所有的组织均能检测到质粒的存在, 质粒在组织中的拷贝数水平随时间的推移呈动态变化, 至6 wk仅在肾脏和血液中检测到外源质粒, 质粒在体内主要以碎片的形式存在.

结论: 外源质粒能被胃肠道吸收, 迅速分布全身各个器官并以碎片的形式在体内存留较长的时间. 外源质粒DNA经胃肠道途径有可能整合到宿主染色体基因组上.

引文著录: 刘建文, 施用晖, 乐国伟, 方希修. 外源质粒DNA经小鼠胃肠道的吸收代谢动力学. 世界华人消化杂志 2004; 12(5): 1108-1113

Revised: December 9, 2003

Accepted: January 8, 2004

Published online: May 15, 2004

AIM: To analyse the changes of foreign plasmid copies in different tissues after uptake via gastrointestinal tract and to evaluate the possibility of foreign plasmid integrating on the host genome.

METHODS: Samples including lung, kidney, spleen, mesenteric lymph node, thymus, gonads, feces, duodenum, large intestine, blood and liver were obtained 1, 3, 6, 24, and 48 h and 3, 6 wk after oral administration of 200 mg plasmid pcDNA3s. PCR technique was used to detect the distribution and kinetics of plasmid in different tissues. Genomic DNA was assayed for integrated plasmid by PCR after purification of high-molecular-weight genomic DNA away from free plasmid by using gel electrophoresis.

RESULTS: Plasmid could be detected in almost all tissues 1 h after oral administration and the copies of plasmid in tissues changed with time. Foreign plasmid could be detected only in kidney and blood at sixth week time. Foreign plasmid mainly as fragment survived in vivo.

CONCLUSION: Foreign plasmid can be absorbed by gastrointestinal tract and distribute in different tissues quickly, surviving as the form of fragment. Foreign plasmid DNA probably integrates into the host genome via the gastrointestinal tract.

- Citation: Liu JW, Shi YH, Le GW, Fang XX. Metabolic kinetics of foreign plasmid DNA uptake via gastrointestinal tract in mice. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi 2004; 12(5): 1108-1113

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1009-3079/full/v12/i5/1108.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.11569/wcjd.v12.i5.1108

哺乳动物胃肠道是外源DNA进入机体的主要器官[1-3]. 外源DNA进入胃肠道后在胃的酸性环境和肠道核酸酶的攻击下, 迅速降解成碎片随粪便排出, 一小部分外源DNA能够以碎片的形式进入机体, 随血液循环分布于各个器官组织中[4]. 外源DNA在肠胃道降解不完全, 能够由肠壁上皮细胞吸收, 经淋巴结, 然后通过外周血液白细胞运送到各个器官中. 以上说明肠胃道对外源DNA并非是一个不可穿越的屏障[4-7]. 与其他营养物质一样, 外源DNA经胃肠道吸收后, 可以递呈到机体的外周与中枢系统中, 可能插入到哺乳动物基因组上, 引起宿主基因组的缺失和重排, 改变宿主基因组相关基因的转录活性,可能激活原癌基因、抑制抑癌基因而导致癌变. 宿主基因组会通过改变DNA甲基化模式这一古老的细胞防御机制来抵抗外源DNA的入侵[8-10]. 因此经口服摄入外源DNA对哺乳动物基因组长期进化的影响是一个不容忽视的问题. 我们采用裸DNA(质粒pcDNA3s)作为研究对象, 考察质粒pcDNA3s经胃肠道给药后在小鼠体内的组织分布及其整合情况.

昆明种小鼠, 6周龄, 雌雄各半, 体质量20±2 g, 由江苏省实验动物中心提供. 大肠杆菌JM109及重组质粒pcDNA3s由本室保存, pcDNA3上BamHI与EcoRI位点之间插入HBsAg抗原基因, 长度为930 bp, 质粒pcDNA3s总长约6 400 bp. pcDNA3s上具有CMV启动子, 可在大肠杆菌中复制, 在真核细胞中表达外源抗原, 是一种典型的真核表达载体. 大量制备质粒, 碱裂解法大量提取5 L发酵液, 酚/氯仿/异戊醇(25:24:1)抽提, 2倍体积无水乙醇沉淀, RNase酶去除RNA, 聚乙二醇纯化, TE(pH8.0)溶解沉淀, -20 ℃保存备用[11].

给每只小鼠灌胃pcDNA3s质粒溶液200 mL (1 g/L), 于灌胃后1, 3, 6, 24, 48 h及3, 6 wk宰杀雌雄各3只及对照组(空白TE溶液)1只. 分离肺、肾、脾、肠系膜淋巴结、胸腺、生殖器官、十二指肠、大肠、血液、肌肉及肝脏等, 分离后的组织分别放入塑料口袋中封口, 在液氮中快速冷冻, 于-80 ℃保存待用. 取50 mg的新鲜组织加入DNA提取缓冲液[0.4 moL/L NaCl, 10 mmoL/L Tris-HCl(pH8.0), 2 mmoL/L EDTA(pH8.0)], 用匀浆器彻底匀浆后, 加入100 g/L的SDS 40 mL, 5 g/L蛋白酶K(终浓度400 mg/L) 32 mL, 充分混匀后放入55 ℃水浴锅中温浴2 h, 加6 moL/L NaCl 300 mL, 混匀, 10 000 rpm/min离心15min, 移上清到另一离心管中, 等体积的酚-氯仿抽提一次, 无水乙醇沉淀, 沉淀得到的DNA用20 mg/L RNA酶溶液400 mL溶解, 37 ℃水浴30 min,等体积的酚-氯仿、氯仿各抽提一次, 无水乙醇沉淀, 沉淀以700 mL/L的乙醇漂洗后用无菌水溶解. 检测DNA样品在260 nm/280 nm下的吸光度A值, 确保二者之比大于1.8, 同时进行5 g/L的琼脂糖凝胶电泳确保DNA的完整性并无RNA[17].

1.2.1 PCR扩增检测组织中质粒DNA: 采用两对引物分别扩增pcDNA3s质粒上部分抗原基因序列(antigen)和整个抗原基因序列(T7-SP6), 引物设计采用oligo6.0, 引物序列: Antigen, P1: 5' TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG GGA GA 3'; P2: 5'TAG TTG ATG TTC CTG GAA GTA 3', 396 bp; T7-SP6, P3: 5'TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG GGA GA 3', P4: 5'GAT TTA GGT GAC ACT ATAG 3', 1 065 bp. PCR反应体积50 mL, 含有10×缓冲液(含MgCl2 15 mmoL), dNTP各200 mmoL/L, 上下游引物各100 pmoL, DNA模板10 mL, TaqDNA聚合酶1 mL, 无菌去离子水36 mL. PCR扩增热循环条件如下: 第1个循环 95 ℃, 10 min; 第2个循环 94 ℃ 1 min, 55 ℃ 1 min, 72 ℃ 1 min 35 cycle; 第3个循环 72 ℃ 10 min 4 ℃保存. 每一种组织来源的样本均设立各自的参比对照系列.

1.2.2 质粒DNA整合情况检测: 按上述方法抽提不同组织及不同时间的基因组DNA. 将各组基因组DNA用EcoRI酶切, 使游离状态及多聚状态质粒变成线性单体(整合入基因组的质粒只能在酶切位点才将基因组切开, 而不能将质粒从基因组上切下来), 8 g/L琼脂糖凝胶电泳回收后再次PCR扩增. 在1 mg无灌胃质粒的鼠基因组DNA中加入不同拷贝数的阳性质粒, 用来评估质粒检测的敏感性.

1.2.3 粪便中筛选pcDNA3s质粒阳性克隆: 收集不同时间的粪便, 重悬于LB液体培养基中, 37 ℃水浴温育1 h后, 涂布于含有Ampicillin的平板上, 24 h后观察细菌菌落的生长情况.

统计学处理 应用SPSS统计软件进行方差分析统计学处理.

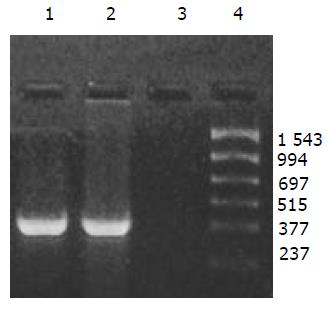

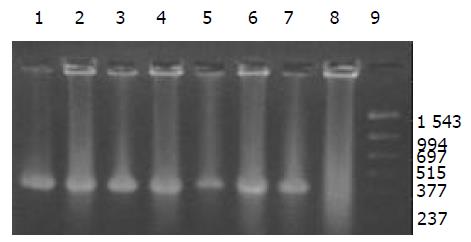

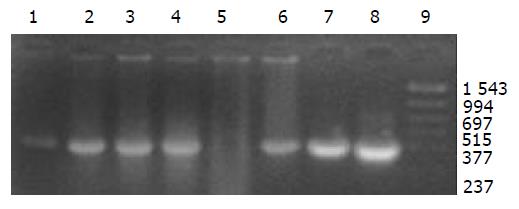

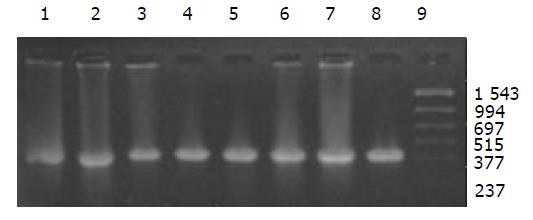

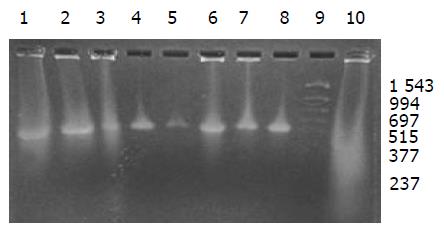

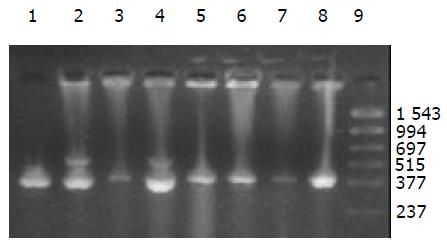

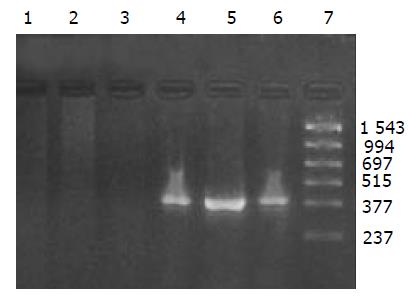

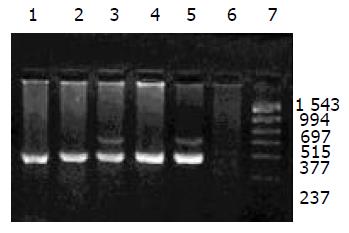

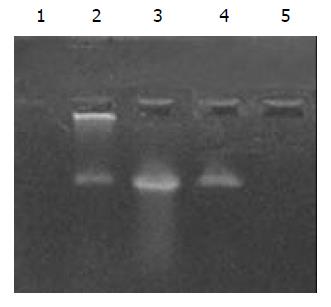

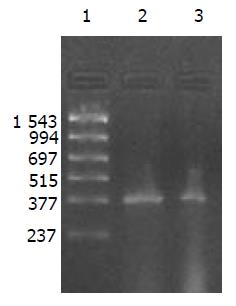

外源质粒在小鼠体内不同组织的质粒拷贝数水平不同,得到阳性扩增条带为396 bp短片段PCR产物(结果见表1、图1-11). 用T7、SP6引物扩增组织每个时间点总DNA结果显示, 仅在极其个别的器官中检测到微弱的阳性条带, 绝大部分组织各时间点均呈阴性, 提示外源质粒在胃肠道环境下迅速被降解, 外源质粒仅以小片段形式进入机体(图12).

| 组织时间 | 肺 | 肾 | 脾 | 肠系膜淋巴结 | 粪便 | 胸腺 | 生殖器官 | 肌肉 | 十二指肠 | 大肠 | 血液 | 肝脏 |

| 30 min | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1 h | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | - | - | + |

| 3 h | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + |

| 6 h | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | ++ | ND | - | + |

| 24 h | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | ++ |

| 3 wk | + | + | - | ++ | + | + | - | ++ | - | ND | ++ | ++ |

| 6 wk | - | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

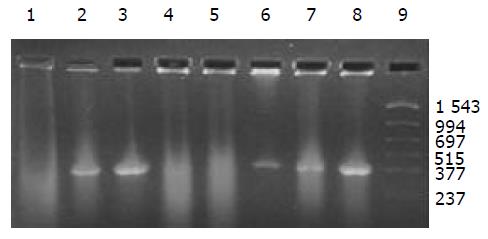

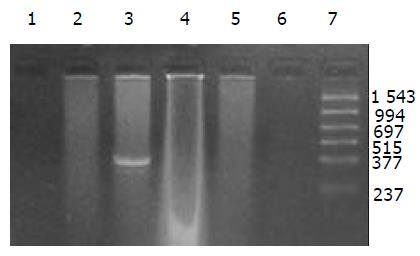

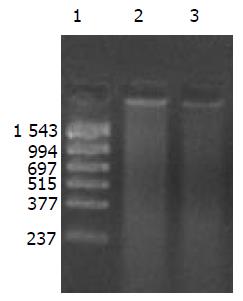

提取6 h时肾脏及其生殖器官的总DNA, 5 g/L的琼脂糖凝胶分离宿主基因组与游离质粒, PCR扩增纯化后的基因组DNA, 可检测到微弱的阳性条带, 说明经口服摄入的外源质粒有可能整合入宿主基因组上. PCR敏感性参照, 取100, 50, 25, 10拷贝质粒DNA加入到1 mg 基因组DNA中, 琼脂糖凝胶观察, 当质粒为100, 50, 25拷贝时PCR检测为阳性, 10拷贝时检测为阴性, 说明PCR的灵敏度为25拷贝. 得到的阳性条带强度较25拷贝的PCR扩增结果弱, 外源质粒如整合入基因组中, 其拷贝数应低于25拷贝(图13).

质粒pcDNA3s上带有ampicillin抗性基因, 因此用ampicillin来筛选粪便细菌中的阳性克隆, 37 ℃于琼脂平板上培养24 h后, 未见到阳性克隆. 当然不能排除外源质粒能够被肠道细菌吸收, 但是不能在细菌中复制形成阳性菌落.

胃肠道是外源DNA进入哺乳动物机体的最主要途径, 肠上皮细胞的巨大表层为营养素和大分子物质(DNA)的吸收创造了条件[12-13]. 外源DNA随着食物的进入而被胃肠道大量吸收, 同时肠道细菌DNA及基因治疗DNA也是哺乳动物外源DNA的来源. 外源DNA经胃肠道吸收后代谢命运及吸收机制一直是人们关心的话题. 黏膜表面, 特别是肠道上段含有大量的抗原递呈细胞、树状细胞、巨噬细胞和B淋巴细胞[12-13]. 他们可以通过胞饮或吞噬作用吞食DNA. 一旦被激活, 树状细胞迁移到淋巴组织中, 特异性递呈抗原到T和B淋巴细胞上, 诱导抗原特异性免疫应答. 残留在肠道中的一小部分DNA碎片直接通过上皮细胞或免疫系统的抗原递呈细胞被小肠黏膜吸收. 如果肠道上皮表面受到破坏, DNA和其他大分子可以向固有层扩散. 说明大部分DNA能够被组织巨噬细胞、免疫系统的树状细胞或其他末端分化吞噬细胞所吞噬[14]. 外源DNA如细菌DNA和质粒DNA上含有非甲基化CpG基序, 可与胃肠道中免疫细胞上的TLR9受体作用, 从而引发免疫应答.

DNA是一种较为稳定的大分子物质, 能够在极端环境下存在, 并且能够在有机体残骸中存在成千上万年[1-2]. 那么外源DNA是否能抵抗哺乳动物胃肠道的酶系统是个令人关注的问题. 我们结果表明, 外源质粒pcDNA3s经胃肠道吸收后, 能够抵抗胃肠道及机体核酸酶的降解, 以碎片形式广泛分布全身各个器官中, 并且在组织中存留较长的时间. 外源质粒给药后在体内的拷贝数水平呈动态变化(见图2-11). 灌胃后1 h, 即可在体内检测到质粒的存在, 并且一直持续到3-6 wk, 仅在肾脏及血液中发现质粒的存在. 3-24 h内, 可检测出外源质粒在粪便中存在, 至6 h时质粒浓度达到最高(P<0.01)(图11). 随着时间的推移, 外源质粒在肝脏中的拷贝数水平有增加的趋势. 质粒在肺中24 h时, 累积浓度达到最高. 质粒浓度在肾脏中各时间点变化不明显. 脾脏在1 h、3 h时质粒的浓度较高, 6 h时开始逐渐减弱(P<0.05), 24 h时急剧减弱(P<0.01), 至3 wk时已无质粒检出. 肠系膜淋巴结至3 wk时质粒累积浓度达到最高(P<0.01), 而且较其他器官高, 肠系膜作为肠道系统的免疫器官, 可识别外源抗原物质(如DNA), 因此肠系膜也是外源质粒的主要累积器官. Schubbert研究表明外源M13由肠黏膜上皮细胞吸收, 经肠系膜淋巴结递呈各个器官中, 肠系膜淋巴结也是外源DNA进入机体的一个主要通道[4]. 与其他器官相比, 胸腺在1 h时质粒的浓度相对较低, 其他时间点质粒浓度无显著差别. 外源质粒在生殖器官中的浓度在1 h、3 h、6 h保持较高的浓度, 24 h开始减弱, 至3 wk时降为零. 外源质粒可在生殖器官中累积, 因此外源质粒是否可以通过生殖系统遗传给下一代值得进一步探讨[15]. 肌肉中的质粒浓度一直较高, 至3 wk时仅次于肠系膜淋巴结. 这与肌纤维细胞具有特殊的结构, 较易吸收外源质粒及递呈抗原有关.

我们采用裸pcDNA3s为研究对象, Blast同源性分析及PCR阴性对照结果表明(图1), PCR扩增目的片段与小鼠基因组、大肠杆菌及食物基因组无同源性序列, 保证了扩增的特异性及可行性. 质粒pcDNA3s作为一种真核表达载体, 同时也为口服DNA疫苗提供了试验依据. 口服灌注质粒pcDNA3s后, 我们观察到了外源质粒在体内各个组织器官中的广泛分布, 随着时间的分布呈动态变化, 并持续较长的时间, 质粒在体内存留的最长时间与Schubbert et al(1997)[4]研究结果有所差异, 可能与载体系统、载体大小及给药数量差异有关. 实验表明外源质粒能够抵抗胃肠道核酸酶的降解, 肠道对外源质粒DNA并不是不可逾越的屏障.

进入细胞的外源质粒一部分以游离体形式存在于胞质中, 一部分进入细胞核整合入宿主染色体中[7]. 我们发现有微弱的外源质粒特异性条带, 初步说明经胃肠道吸收后外源质粒会整合到宿主染色体基因组. Schubbert et al(1997)将插入有M13DNA的老鼠脾细胞DNA重克隆至质粒载体中, 也分离出1.3 kb M13 DNA片段, DNA序列分析发现与该片段共价相连的DNA与老鼠IgE受体基因有70%的同源性. 但是与PCR敏感性参照比较, 整合的外源质粒低于25拷贝. 如果以30个拷贝数来进行计算, 也就是外源质粒进入宿主细胞后, 在1 mg细胞染色体DNA中引起基因突变的最大可能性为30. 小鼠的1个细胞染色体组大约含有3×109个碱基对, 重量为6 g, 那么1 mg的染色体组大约含有1.5×105的染色体组. 实际上, 哺乳动物染色体组中的基因是不断地发生着自发突变, 只要其发生的概率对于每一个基因来说不超过10-6, 就不会对哺乳动物的健康造成影响. 由于每个细胞染色体组中大约含有7.5×104个基因, 那么1.5×105个细胞染色体组就含有11.25×109个基因, 如果外源DNA在1.5×105个细胞染色体中造成30次突变, 那么他的突变概率就是2.7×10-9. 根据计算的结果和正常所容许的基因突变概率10-6相比, 外源质粒DNA经胃肠道吸收后可能引起的基因突变概率要比细胞的自发突变率低2 700倍[16-32]. 因此认为外源质粒即使有可能和细胞染色体组的DNA发生随机整合, 对于其安全性也是不足为虑的.

外源质粒DNA作为大分子通过胃肠道途径摄入后被不完全降解后吸收, 以碎片形式分布于全身各个组织中. 外源DNA经肠黏膜吸收机制还不清楚, 肠黏膜上的M细胞或淋巴细胞是否作为外源DNA穿透肠壁的主要通道, 肠黏膜细胞上是否存在DNA结合蛋白介导外源DNA的吸收, 不同的生理状态下外源DNA的吸收情况等还有待于深入研究. 外源DNA经胃肠道吸收后可能整合到宿主基因组上, 引起基因组突变及甲基化等不可预见后果. 因此, 外源DNA在哺乳动物中的吸收代谢必然会影响宿主基因组的功能, 从而对哺乳动物的进化产生影响.

| 1. | Doerfler W, Schubbert R. Uptake of foreign DNA from the environment: the gastrointestinal tract and the placenta as portals of entry. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1998;110:40-44. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Doerfler W. Foreign DNA in mammalian systems. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, New York, Chichester, Brisbane, Singapore, Toronto. 2000;147-156. |

| 3. | Doerfler W, Remus R, Müller K, Heller H, Hohlweg U, Schubbert R. The fate of foreign DNA in mammalian cells and organisms. Dev Biol (Basel). 2001;106:89-97; discussion 143-160. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Schubbert R, Renz D, Schmitz B, Doerfler W. Foreign (M13) DNA ingested by mice reaches peripheral leukocytes, spleen, and liver via the intestinal wall mucosa and can be covalently linked to mouse DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:961-966. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 5. | Schubbert R, Hohlweg U, Renz D, Doerfler W. On the fate of orally ingested foreign DNA in mice: chromosomal association and placental transmission to the fetus. Mol Gen Genet. 1998;259:569-576. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 6. | Hohlweg U, Doerfler W. On the fate of plant or other foreign genes upon the uptake in food or after intramuscular injection in mice. Mol Genet Genomics. 2001;265:225-233. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 7. | Palka-Santini M, Schwarz-Herzke B, Hösel M, Renz D, Auerochs S, Brondke H, Doerfler W. The gastrointestinal tract as the portal of entry for foreign macromolecules: fate of DNA and proteins. Mol Genet Genomics. 2003;270:201-215. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 8. | Doerfler W, Hohlweg U, Müller K, Remus R, Heller H, Hertz J. Foreign DNA integration--perturbations of the genome--oncogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;945:276-288. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 9. | Müller K, Heller H, Doerfler W. Foreign DNA integration. Genome-wide perturbations of methylation and transcription in the recipient genomes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:14271-14278. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 10. | Remus R, Kämmer C, Heller H, Schmitz B, Schell G, Doerfler W. Insertion of foreign DNA into an established mammalian genome can alter the methylation of cellular DNA sequences. J Virol. 1999;73:1010-1022. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatia T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual[M]. 3nd ed. New York: Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory Press 2001; 26-50. |

| 12. | Ren JM, Zou QM, Wang FK, He Q, Chen W, Zen WK. PELA microspheres loaded H. pylori lysates and their mucosal immune response. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:1098-1102. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 13. | Chen XQ, Zhang WD, Song YG, Zhou DY. Induction of apoptosis of lymphocytes in rat mucosal immune system. World J Gastroenterol. 1998;4:19-23. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 14. | Beever DE, Kemp CF. Safety issues associated with the DNA in animal feed derived from genetically modified crops A review of scientific and regulatory procedures. Nutri Abstr Rev. 2000;70:175-182. |

| 15. | Kang KK, Choi SM, Choi JH, Lee DS, Kim CY, Ahn BO, Kim BM, Kim WB. Safety evaluation of GX-12, a new HIV therapeutic vaccine: investigation of integration into the host genome and expression in the reproductive organs. Intervirology. 2003;46:270-276. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 16. | Haworth R, Pilling AM. The PCR assay in the preclinical safety evaluation of nucleic acid medicines. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2000;19:267-276. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 17. | Ledwith BJ, Manam S, Troilo PJ, Barnum AB, Pauley CJ, Griffiths TG 2nd, Harper LB, Schock HB, Zhang H, Faris JE, Way PA, Beare CM, Bagdon WJ, Nichols WW. Plasmid DNA vaccines: assay for integration into host genomic DNA. Dev Biol (Basel). 2000;104:33-43. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Ledwith BJ, Manam S, Troilo PJ, Barnum AB, Pauley CJ, Griffiths TG 2nd, Harper LB, Beare CM, Bagdon WJ, Nichols WW. Plasmid DNA vaccines: investigation of integration into host cellular DNA following intramuscular injection in mice. Intervirology. 2000;43:258-272. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 19. | Manam S, Ledwith BJ, Barnum AB, Troilo PJ, Pauley CJ, Harper LB, Griffiths TG 2nd, Niu Z, Denisova L, Follmer TT, Pacchione SJ, Wang Z, Beare CM, Bagdon WJ, Nichols WW. Plasmid DNA vaccines: tissue distribution and effects of DNA sequence, adjuvants and delivery method on integration into host DNA. Intervirology. 2000;43:273-281. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 20. | Wang Z, Troilo PJ, Wang X, Griffiths TG, Pacchione SJ, Barnum AB, Harper LB, Pauley CJ, Niu Z, Denisova L. Detection of integration of plasmid DNA into host genomic DNA following intramuscular injection and electroporation. Gene Ther. 2004;11:711-721. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 21. | Vandegraaff N, Kumar R, Burrell CJ, Li P. Kinetics of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV) DNA integration in acutely infected cells as determined using a novel assay for detection of integrated HIV DNA. J Virol. 2001;75:11253-11260. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 22. | Lin NT, Chang RY, Lee SJ, Tseng YH. Plasmids carrying cloned fragments of RF DNA from the filamentous phage (phi)Lf can be integrated into the host chromosome via site-specific integration and homologous recombination. Mol Genet Genomics. 2001;266:425-435. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 23. | Oh YK, Kim JP, Hwang TS, Ko JJ, Kim JM, Yang JS, Kim CK. Nasal absorption and biodistribution of plasmid DNA: an alternative route of DNA vaccine delivery. Vaccine. 2001;19:4519-4525. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 24. | Imboden M, Shi F, Pugh TD, Freud AG, Thom NJ, Hank JA, Hao Z, Staelin ST, Sondel PM, Mahvi DM. Safety of interleukin-12 gene therapy against cancer: a murine biodistribution and toxicity study. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14:1037-1048. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 25. | Morris-Downes MM, Phenix KV, Smyth J, Sheahan BJ, Lileqvist S, Mooney DA, Liljeström P, Todd D, Atkins GJ. Semliki Forest virus-based vaccines: persistence, distribution and pathological analysis in two animal systems. Vaccine. 2001;19:1978-1988. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 26. | Lunsford L, McKeever U, Eckstein V, Hedley ML. Tissue distribution and persistence in mice of plasmid DNA encapsulated in a PLGA-based microsphere delivery vehicle. J Drug Target. 2000;8:39-50. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 27. | Parker SE, Monteith D, Horton H, Hof R, Hernandez P, Vilalta A, Hartikka J, Hobart P, Bentley CE, Chang A. Safety of a GM-CSF adjuvant-plasmid DNA malaria vaccine. Gene Ther. 2001;8:1011-1023. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 28. | Bureau MF, Naimi S, Torero Ibad R, Seguin J, Georger C, Arnould E, Maton L, Blanche F, Delaere P, Scherman D. Intramuscular plasmid DNA electrotransfer: biodistribution and degradation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1676:138-148. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Hulse DJ, Romero CH. Fate of plasmid DNA encoding infectious bursal disease virus VP2 capsid protein gene after injection into the pectoralis muscle of the chicken. Poult Sci. 2002;81:213-216. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 30. | Imboden M, Shi F, Pugh TD, Freud AG, Thom NJ, Hank JA, Hao Z, Staelin ST, Sondel PM, Mahvi DM. Safety of interleukin-12 gene therapy against cancer: a murine biodistribution and toxicity study. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14:1037-1048. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 31. | Dupuis M, Denis-Mize K, Woo C, Goldbeck C, Selby MJ, Chen M, Otten GR, Ulmer JB, Donnelly JJ, Ott G. Distribution of DNA vaccines determines their immunogenicity after intramuscular injection in mice. J Immunol. 2000;165:2850-2858. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 32. | Al-Qarawi AA, Ali BH, Al-Mougy SA, Mousa HM. Gastrointestinal transit in mice treated with various extracts of date (Phoenix dactylifera L.). Food Chem Toxicol. 2003;41:37-39. [PubMed] [DOI] |