MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and grouping

Forty patients with endoscopically proven active gastric or duodenal ulcer at our hospital from June, 2001 to May, 2002 entered into the study. They were randomly assigned to three groups: RAB group (n = 15), OME group (n = 15) and PAN group (n = 10). The male/female ratio of patients was 9:6, 8:7, 6:4 in the three groups respectively. Their age (mean) was 20-61 (34.5 ± 7.8) years, 22-60 (30.6 ± 6.7)years and 25-59 (29.3 ± 6.5) years respectively. Twenty healthy volunteers (10 men and 10 women) were enrolled as the control group, aged from 18 to 60 years (mean 25.7 ± 9.5).

Methods

Administering method This study was an open comparative trial. With a single oral dose, every one was administered 10 mg RAB, 20 mg OME or 40 mg PAN respectively, ambulatory intragastric pH measurements were then performed. All subjects ceased the drugs that might affect acid secretion and gastrointestinal motility 2 wk before the study.

Instruments and processes[3] Portable pH recorder (DIGITRAPPER MKIII, CTD Co., Sweden). After fasted for 12 h, an electrode was placed via a nostril into the stomach at 8 am, to record the baseline pH for an hour, a dose of drug was given to one patient at 9 am, pH was recorded continuously for hours. All participants kept their normal daily activities and consumed their customary diet, except to abstain from drinking acid and alkali beverages during the test period. The pH electrode was withdrawn at the following morning 9 am, pH data were downloaded onto a computer for analysis.

Measuring indicator The impact of the three agents on NAB (identifying criterion[4]: Intragastric pH dropped to < 4 and remained below that level for at least 1 h during the 12 h of night sleeping period after the dose of PPI). The impact of the three agents on NAKA (identifying criterion[5]: The time that intragastric pH remained > 4 lasted for > 1 h from 0:00 to 8 am).

Statistical analysis

All data were processed by a computer. Data were presented as the mean ± SD. Comparisons between two groups and among three groups were made using the Student t test or t' test followed an analysis of covariance. P < 0.05 was considered to have statistical significance.

DISCUSSION

NAB and NAKA are two common clinical phenomena, but the developing mechanisms are remain unclear. Our attention was to investigated the effects of PPIs on NAB and NAKA.

NAB was defined as the occurrence of intragastric pH dropped to below 4 and remained below that level for at least 1 h during the 12 h of night sleeping period (typically the second 6-hours) after the dose of PPI[1,4]. This study showed that the pH (1.84 ± 0.55) of NAB was significantly higher in RAB group than in OME group and PAN group (P < 0.05), the persisting time of NAB was shortened. Additionally, the occurrence of NAB was lower in RAB group than in PAN group. The above results suggested that RAB had an advantage over OME and PAN on suppressing NAB, which was consistent with other reports[6,7]. It might contribute to the pharmacological features of RAB such as longer half-life, rapid onset of action, acid-stability, no influences on foods, dosing time or patterns[8-10]. NAB had a high occurrence after midnight and typically in the second 6-hours during night sleeping[1,4,11]. NAB after taking PPIs was first reported by Peghini and Katz[4]. Peghini et al[12] considered that NAB could be explained by food-related factors (for example, the absence of the buffering effect of meals after midnight) which resulted in weakened acid-inhibiting efficacy of PPIs and increased night acid production. This might help to explain why the acid-suppressing effect of PPIs during daytime was greater than that during nighttime. According to the fact that adding a dose of H2RA at bed time could produce a much better controllable action than that of PPIs on NAB. Peghini et al[4,13,14] suggested that histamine played a major role in nocturnal acid secretion. A study revealed that 70% of patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD) receiving PPIs had NAB which was often accompanied by esophageal acid exposure. The prevalence of ineffective esophageal motility and low LES pressure was significantly higher in refluxers than in non-refluxers[15], so GERD was considered to correlate with NAB closely. This might be the result of gastric acid secretion following a circadian profile which was characterized by an increase in the evening, with a peak at about midnight[16]. This might explain why only some refluxers developed esophagitis. There was another opinion that eradication of H. pylori appeared to be closely related to the occurrence of nocturnal NAB when a dose of PPI was given[17]. There were important clinical implications of NAB, because there existed a close relationship between night acid-control and GERD as well as peptic ulcer. Esophageal protective mechanism was decreased during this time and it was unbeneficial for ulceric mucosa to restore[18,19]. It was thought that NAB might be particularly injurious to the esophageal mucosa and might arise lasting nocturnal heartburn or acid regurgitation and even respiratory complaints. Hence, there was a clinical rationale and greater importance for reducing or abolishing nocturnal acid secretion and increasing intragastric pH or intra-esopgageal pH in treatment of acid-related disorders to promote the healing of peptic ulcer, severe GER and Barrett's esophagus in order to improve the quality of life[20]. But NAB was also reckoned to prove reversely the safety of PPI (i.e. it was extremely difficult to render achlorhydric)[11]. Many studies supported that the addition of a low dose of H2RA did enhance the control effect on NAB of PPIs because H2RAs reduced basal gastric acid secretion, H2RA nizatidine has been known to stimulate gastric emptying and elevate LES pressure and therefore decrease NAB as well as nightly reflux[21], low dose of H2RA following a provocative dinner or a large fatty meal might effectively reduce esophageal acid exposure. Being prone to produce a tolerance to H2RA due to its long-term intaking, an intermittent dosing fashion might be an optimal approach[22].

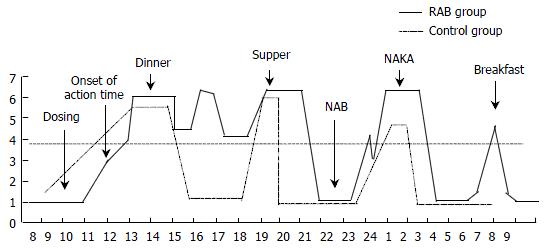

NAKA was also termed as "spontaneous nocturnal gastric alkalinization" (SNGAK), "spontaneous nocturnal alkalinization" (SNA), "nocturnal anhydrochloric wave" and "inversion of gastric pH"[23-25], which was defined as a phenomenon that an abrupt physiological or pathological raise of intragastric pH to above 4 to 6 after sleeping (mostly in the early morning). The prevalence of NAKA ranged between 40%-80% in normal populations, mostly beginning in the latter part of the night. Bianco et al[25] found that SNA lasted for 87.82 ± 12.47 min/time in normal volunteers and for 3.27 ± 1.62 min/time in patients with duodenal ulcer. Ke et al[26] reported that NAKA presented in 67% of normal group, lasting for 169.7 ± 40.2 min (total), and raised in 70% of patients with duodenal ulcer, lasting for 57.6 ± 12.0 min (total). In this study, NAKA presented in 45% (9/20) of normal subjects, which sustained for 135.0 ± 73.8 min (total), and in 55% (22/40) of patients with duodenal ulcer. The results were lower than the above, the mean sustaining time of NAKA was 220.4 ± 100.6 min (total) in patients with duodenal ulcer after a single administration of PPI. These findings indicated that RAB might increase the pH of NAKA and prolong persisting time of NAKA. We have previously conducted a simultaneous monitoring of intragastric pH and bile in normal subjects and patients with duodenal gastric reflux (DGR), and found that the pH and cholerythrin exhibited 2 models and 4 types[27]. The 2 models were simultaneous and non-simultaneous raise of pH and cholerythrin, and the 4 types were simultaneouse raise and drop of pH and cholerythrin. pH raised alone and cholerythrin raised alone. The test of neutralizing bile with gastric juice in vitro showed that until the absorbency had already raised to 0.900 when bile concentration was 20%, while pH remained at 1 or so. Furthermore, only when bile concentration raised to > 60%, did gastric pH begin to raise to > 4, suggesting that it was not until bile reached to a considerable level when it had an influence on intragastric pH. As bile is nocuous to esophageal mucosa, so only a solitary pH raise produces a protective action. NAKA was proposed by Bianco et al[28] at first in 1970s, there were several opinions about its pathophysiological mechanism. NAKA appeared to be a kind of self-protective mechanism for gastric mucosa against the damages of acid and mucosa-injuring agents, and helping expulse H+ to gastric cavity continuously so as to relieve clinical symptoms. In this trial, all 3 PPIs increased peak value and persisting time of NAKA (there was a significant difference in comparison with the control). The increase was more prominent for RAB than for OME and PAN, one likely explanation was that H+-K+ATPase was inhibited much more. Further investigation is needed. Based on earlier studies[23,27,29], we hypothesed that NAKA was related to DGR, this hypothesis was supported by conclusions of other countries[30,31]. Alkali reflux mostly occurred during MMC phase II and phase III, suggesting that NAKA together with duodenal uncoordinated motor activity could lead to the reflux of duodenal juice (not always bile) into gastric cavity and hence antrum "alkalinization" state at the end of phase III. NAKA was thought to be strongly related to sleeping and interrupted by waking up[31]. Some investigators deduced that NAKA correlated with reduced vagal tension and chlecystectomy as well as modulation of gastric secretions[24,32]. There were evidences that ulcer patients did not show SNA phenomenon before treatment, but the therapy led it to recurrence, and the lack of SNA in duodenal ulcer patients was so frequent that its absence might be a diagnostic sign of peptic ulcer (positively predictive value 82%)[25,33]. In addition, we had an interesting observation that NAKA always appeared following NAB (Figure 1). There have been no findings concerning this phenomenon yet, and its etiology needs to be identified.

Figure 1 Simulating figure of NAB and NAKA.

NAB and NAKA all occurred after midnight, and NAKA always appeared after NAB. Compared with the control group (didn’t receive either PPI or placebo), RAB increased the pH of NAKA as well as prolonged the persisting time of NAKA.

NAB is the most notable limitation of PPIs used at present. By comparison we can understand that available PPIs are unable to resolve the problem of NAB, including rabeprazole. In summary, we have shown that a single dose of 10 mg rabeprazole can achieve a much superior acid-suppressing efficacy as compared to omeprazole and pantoprazole. It can elevate pH of NAB, shorten persisting time of NAB, increase pH as well as sustaining time of NAKA. These findings show that rabeprazole may provide a profound control on nocturnal gastric acid secretion. However, there remain problems demanding further evaluations. For example, whether it is beneficial by increasing the dose or administering time of rabeprazole (i.e. twice daily) or an on-demand treatment[19] should be given to enhance the acid-inhibiting efficacy of rabeprazole, whether the onset of NAKA correlates with more effective inhibiting on H+-K+ATPase of rabeprazole, etiology and clinical implications of NAB and NAKA, and why NAKA is always present after NAB.