Published online Sep 7, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i33.109800

Revised: June 8, 2025

Accepted: August 4, 2025

Published online: September 7, 2025

Processing time: 101 Days and 18 Hours

The number of population-based studies on unclassified inflammatory bowel disease (IBD-U) is very limited.

To evaluate the long-term incidence, disease course and surgery rates of IBD-U in a prospective population-based cohort.

The present study is a continuation of the well-established Veszprem IBD cohort with patient inclusion between 1977 and 2018. Both in-hospital and outpatient records were collected. The source of age- and gender-specific demographic data was derived from the Hungarian Central Statistical Office. Medical therapy, surgery and change in disease phenotype were analyzed.

Data of 119 incident IBD-U patients were analyzed [male/female: 55/64; median age at diagnosis: 34 years (interquartile range: 24-47.5)]. Adjusted mean incidence rate was 0.76 (95%CI: 0.63-0.9)/105 person-years in the total study period. Disease extent at diagnosis was extensive (pancolitis) in 56.3%. Twenty-two of 119 (18.5%) patients were reclassified to Crohn’s disease during follow up, the probability of developing terminal ileum involvement was 6.8%, while perianal disease developed in 5% (n = 6). The probability of receiving biological therapy in patients diagnosed after the year 2000 (n = 62), was 15.5% (SD: 4.8) at 5 years. The overall resective surgery rate was 16.8%. Segment resection was performed in 5.0% of the patients, and 11.8% underwent subtotal or total colectomy. The cumulative probability of resective surgery was 7.6% (SD: 2.4) at 1 year, 9.3% (SD: 2.7) at 5 years, 13.5% (SD: 3.3) at 10 years, and 18.5% (SD: 3.9) at 20 years.

These data extend our knowledge on the overall burden of IBD-U. Colonic involvement was extensive in a high proportion of IBD-U. Disease reclassification to Crohn’s disease was relatively high. High rates of biological therapy and surgery rates support a relatively severe disease course of IBD-U.

Core Tip: This is the one of the first comprehensive, population-based study from Eastern Europe evaluating the long-term incidence, disease progression, and outcomes of unclassified inflammatory bowel disease (IBD-U). Analyzing data from 119 patients over four decades, we identified a high rate of reclassification to Crohn’s disease and substantial use of biological therapies and surgeries, reflecting a more severe disease phenotype than previously reported. These findings challenge the notion of IBD-U as a benign or transitional diagnosis and underscore the need for tailored therapeutic strategies and further longitudinal research.

- Citation: Balogh F, Gonczi L, Angyal D, Golovics PA, Pandur T, David G, Erdelyi Z, Szita I, Ilias A, Lakatos L, Lakatos PL. Incidence, disease course, therapeutic strategies and outcomes of inflammatory bowel disease-unclassified patients in Western Hungary: A population-based cohort. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(33): 109800

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i33/109800.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i33.109800

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), encompassing Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), are chronic inflammatory disorders of the gastrointestinal system. Diagnosis is based on an integrated approach that combines clinical assessment - including symptoms, medical history, and physical examination - with biological, endoscopic, ultrasonographic, radiological, and histological findings[1]. Moreover, in certain cases, the clinical presentation of UC and Crohn’s colitis is so similar that differentiation between the two conditions is not possible in approximately 10% of instances[2,3]. The term "indeterminate colitis" was first introduced by Kent et al[4] in 1970 to describe colectomy cases exhibiting overlapping features between CD and UC and/or insufficient evidence to establish a final diagnosis. In 2005, the World Congress of Gastroenterology introduced the term "inflammatory bowel disease unclassified" (IBD-U) to refer to presurgical cases where clinical presentation, endoscopic evaluation, and biopsy findings suggest IBD, but further differentiation is not feasible[5]. The diagnosis of IBD-U is most commonly attributed to factors such as IBD in its fulminant or early stages, limited clinical or pathological data, difficulty in identifying atypical pathological variants of UC or CD, and challenges in distinguishing IBD from non-IBD conditions or other comorbidities.

In everyday practice, patients are usually categorized as having IBD-U when endoscopic findings reveal features such as extensive severe colitis, segmental involvement with rectal sparing, and variability in disease severity across different colonic segments. A characteristic patchy distribution is often observed, marked by broad regions of irregular ulceration interspersed with areas of mucosa that appear macroscopically normal. Histologically, these cases demonstrate fissuring ulceration, mucosal islands with regular epithelial lining, preserved goblet cell populations, and mild to moderate inflammation. Transmural inflammation is typically associated with areas of severe ulceration. The fissures are generally short, V-shaped clefts or cracks with minimal inflammatory infiltrate, frequently multiple, and predominantly located in regions of extensive ulceration. Additionally, prominent vascular proliferation is commonly noted at the base of these ulcerations. Granulomas, transmural lymphoid aggregates, and crypt abscesses are absent in these presentations[6].

Infectious colitis and other potential causes of colitis must be ruled out through stool cultures and histopathological analysis[7].

While some experts view IBD-U as a provisional diagnosis, given that many patients are subsequently reclassified as UC or CD during follow-up, others advocate for its recognition as a distinct category within IBD, as a proportion of patients retain the IBD-U diagnosis even after extended follow-up periods[8,9]. Research specifically focused on IBD-U remains limited, providing insufficient evidence to guide treatment decisions based on robust data. Existing studies suggest that treatment approaches for IBD-U frequently resemble those used in UC patients. To date, only a few population-based cohort studies have thoroughly investigated the natural history of IBD-U, beyond documenting incidence rates and subsequent reclassification into established IBD subtypes[10,11].

The present study is a continuation of the Veszprem IBD population-based cohort with a follow-up of the incidence and disease course of patients with an initial IBD-U diagnosis since 1977. We aimed to analyze incidence rates, demographic characteristics and disease phenotype at diagnosis, medication exposures and surgical needs during follow-up in the prospective population-based Veszprem Province database, including incident IBD-U patients diagnosed between January 1, 1977 and December 31, 2018.

The present study is based on a prospective, population-based cohort from Veszprem County, Hungary. Veszprem County is an administrative region in western Hungary with a population of 335361 residents, according to the 2011 national census[12]. The Veszprem IBD cohort is a well-established inception cohort that was originally initiated in 1977. Detailed methodological and demographic descriptions of this cohort have been provided in numerous previous publications, both from earlier and more recent years. Patient inclusion for this cohort occurred between January 1, 1977 and December 31, 2018, with a total of 2435 incident IBD cases. Demographic and clinical characteristics of IBD-U, CD and UC patients were evaluated. Detailed demographic data were collected, and disease phenotype was assessed at diagnosis and during follow-up. IBD-U was pragmatically defined as patients with colonic disease, not fulfilling all required criteria for either CD or UC and/or presenting with phenotypic characteristics for both diseases, but unequivocally presenting with chronic IBD and requiring treatment. Disease classification (location, behavior, and extent) in patients with established CD and UC was made according to the Montreal classification[5]. Similar classification was used for colonic disease extent in IBD-U patients. Disease reclassification from IBD-U to CD was based on definitive appearance of CD associated phenotype at reassessment, as stenosing or penetrating disease, ileal manifestation or perianal manifestation. Of note, the main IBD-clinicians were unchanged throughout the capture period, which made the assessment criteria and case identification stable. Repeated histological evaluations were not available in all patients, and histological results were inconclusive in some patients for differentiating CD from UC (see limitations).

Medication exposures were evaluated using cumulative exposure rates and assessing ‘maximal therapeutic step’ distributions. Biological therapies, which became widely available and covered by the National Health Insurance Fund of Hungary in 2008, were considered in assessing temporal trends. Resective surgery rates, including segment bowel resections and sub-total/total colectomies were recorded. Information on medical therapies and surgeries was gathered from patient visit records and prescription records and updated annually. In temporal analyses, time to disease behavior change, time to initiation of biological therapy, and time to surgical outcomes were registered. Mortality data, including time to death, were also recorded, and follow-up times were adjusted accordingly. Gender, smoking history, continuous vs remitting disease, anemia, macroscopic assessment of mucosal involvement (‘CD like’ vs ‘UC like’) and reclassification were assessed as predictive factors for first resective surgery in IBD-U patients.

All patients diagnosed with IBD-U within the study region during the specified period were included. Diagnoses were meticulously reviewed by an expert gastroenterologist specializing in IBD, utilizing the Lennard-Jones[13] and Copenhagen Diagnostic Criteria[14]. The date of diagnosis was defined as the point when the necessary diagnostic tests (endoscopic, histological, and/or radiological evidence) were completed to confirm IBD-U. Case validation and oversight were conducted by the lead IBD specialist gastroenterologist at Csolnoky F. County Hospital during data centralization. Patient follow-up extended until December 31, 2020, or until emigration or death. Data were collected prospectively from the time of diagnosis and annually reviewed using public health records and questionnaires completed by treating physicians to address missing or additional information. Patient information was collected from four general hospitals in the province and their affiliated gastroenterology outpatient units. Centralization of the provincial IBD registry occurred in Veszprem, with most patients monitored at Csolnoky F. County Hospital, with a specialized IBD gastroenterology outpatient unit, which also functions as a secondary referral center for IBD care in the region. Since 2018, data collection has been enhanced through the National eHealth Infrastructure, a cloud-based platform providing access to inpatient and outpatient medical records, diagnostic results, and medication prescriptions, ensuring greater accuracy in cohort data. Disease phenotype, treatments, and surgical interventions were updated annually by treating physicians using standardized data forms. Detailed descriptions of the data collection methodology, case ascertainment processes, and the geographical and socioeconomic context of the study area are available in previous publications on this inception cohort.

Continuous variables are expressed as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR), while categorical variables are presented as counts with corresponding percentages and SD. The t-test or Mann-Whitney U test was employed to compare continuous variables, and the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables, as appropriate. Cumulative probabilities of medication use and changes in disease phenotype were estimated using Kaplan-Meier analysis, with comparisons between groups conducted using the log-rank test. Multivariate regression analysis was performed to identify predictors of resective surgery in IBD-U patients. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software version 20.0 (Chicago, IL, United States).

The study was approved by the Csolnoky F. Province Hospital Institutional Committee of Science and Research Ethics (193/2004, 0712/2009, and 2/2021).

Nine hundred and forty-six patients were diagnosed with CD, 1370 patients were diagnosed with UC and 119 patients were diagnosed with IBD-U in the total Veszprem-IBD cohort between 1977 and 2018. The percentage of IBD-U at diagnosis was 4.89% (119/2435) in the total study population and 8.68% in the UC patients. Median follow-up time was 18.0 years (IQR: 11-24).

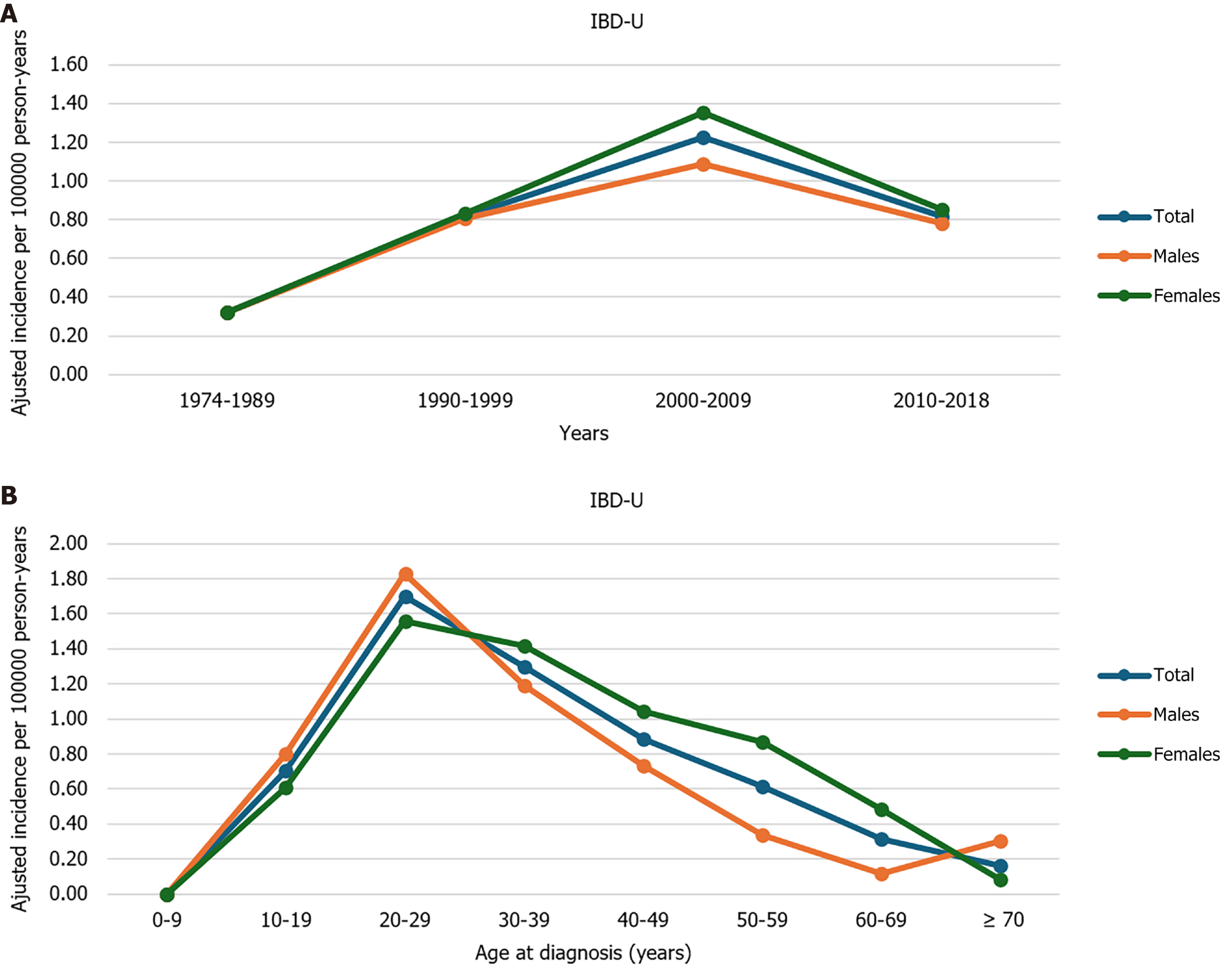

The adjusted mean incidence rate was 0.76 (95%CI: 0.63-0.9)/105 person-years in the total study period, and 0.96 (95%CI: 0.79-1.16)/105 person-years between 1990-2018. Trends in incidence rates and age-specific mean incidence rates are shown in Figure 1. Peak disease onset was at 20-29 years of age.

Data of 119 incident IBD-U patients were analyzed [male/female: 55/64; median age at diagnosis: 34 years (IQR: 24-47.5)]. Disease extent at diagnosis was proctitis in 7.6%, left-sided colitis, or isolated right-sided colitis in 36.1%, and extensive (pancolitis) in 56.3%. The percentage of active smokers at diagnosis was 26.9%, while the percentage of ex-smokers was 19.3%. A comparison of the demographic characteristics of IBD-U, CD and UC patients is summarized in Table 1.

| IBD-U (n = 119) | UC (n = 1370) | CD (n = 946) | P value | |

| Male gender | 55 (46.2) | 702 (51.2) | 496 (52.4) | 0.032 |

| Median age at diagnosis (IQR), years | 34 (24-47.5) | 36 (26-51) | 28 (22-40) | 0.042 |

| Colonic extent at diagnosis | N/A | 0.002 | ||

| Proctitis | 9 (7.6) | 333 (24.3) | ||

| Left-sided colitis | 43 (36.1) | 664 (48.5) | ||

| Pancolitis | 67 (56.3) | 373 (27.2) | ||

| Smoking | 0.001 | |||

| Non-smoker | 64 (53.8) | 921 (67.2) | 434 (45.9) | |

| Active smoker | 32 (26.9) | 201 (14.7) | 409 (43.2) | |

| Ex-smoker | 23 (19.3) | 248 (18.1) | 103 (10.9) | |

| Diagnostic delay from symptom onset to diagnosis | 0.089 | |||

| Less than 1 year | 80 (67.2) | 962 (70.2) | 562 (59.4) | |

| 1-2 years | 29 (24.4) | 282 (20.6) | 262 (27.7) | |

| More than 2 years | 10 (8.4) | 126 (9.2) | 122 (12.9) |

Extraintestinal manifestations during the total follow-up were as follows: Hepatic manifestations n = 18 (15.1%), primary sclerosing cholangitis n = 5 (4.2%), arthritis n = 27 (22.7%), ocular n = 4 (3.4%), skin manifestations n = 5 (4.2%). Anemia of chronic diseases or iron deficiency anemia were present in n = 55 (46.2%) of the patients.

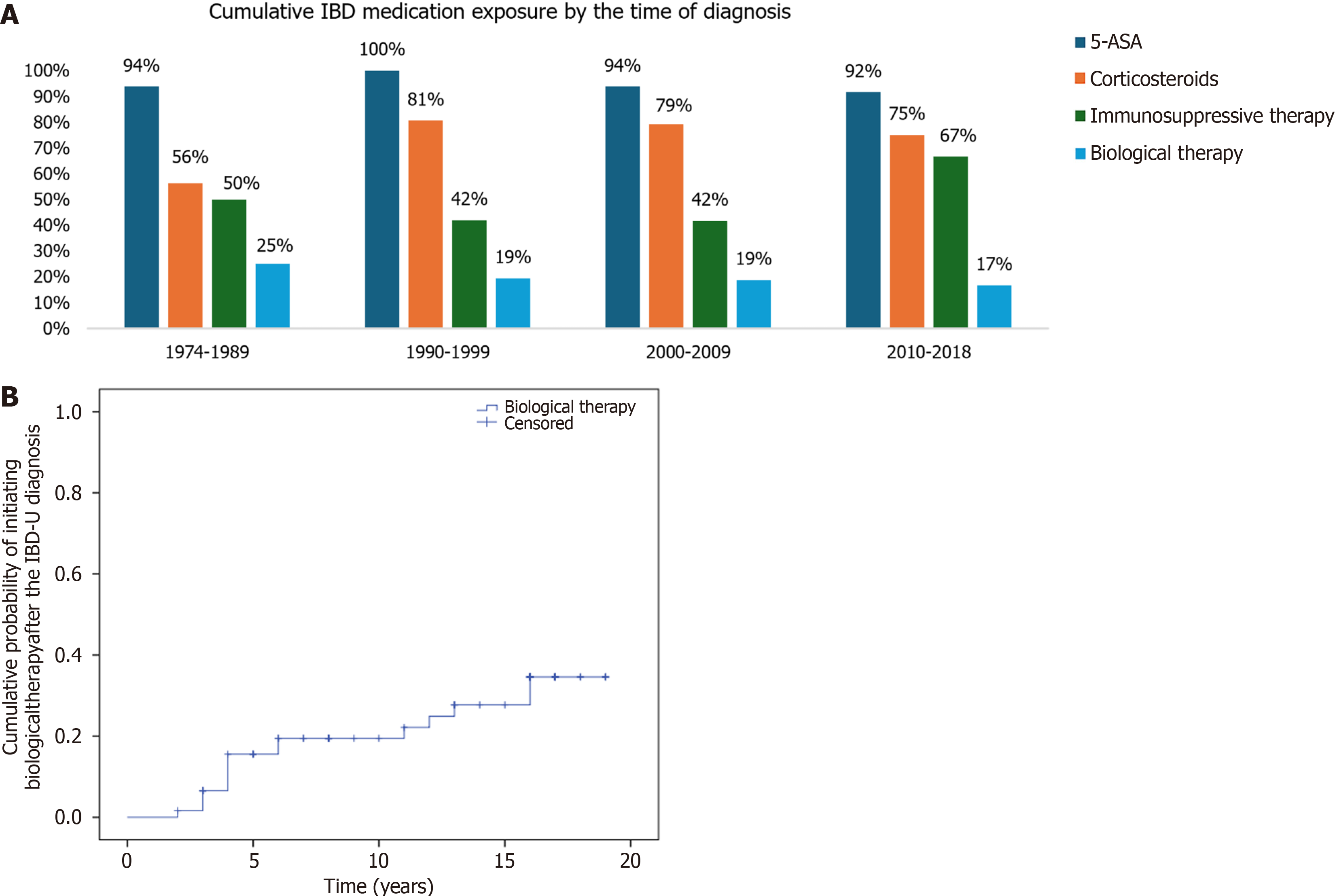

Distribution of maximal therapeutic steps during the course of follow-up (median 18.0 years, IQR: 11-24) were 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) in 20.2% of the patients, systemic corticosteroids in 24.4%, immunosuppressive therapy in 35.3%; biological therapy in 19.3%. Overall exposure to 5-ASA was 95.0% (113/119), systemic corticosteroids 76.5% (91/119), immunosuppressives 50.4% (60/119) and biological exposure was 19.3% (23/119). Cumulative exposure to IBD specific groups of medications stratified by the time of diagnosis is shown in Figure 2A.

The probability of receiving biological therapy in patients diagnosed after the year 2000 (n = 62), was 15.5% (SD: 4.8) at 5 years, and 19.4% (SD: 5.3) at 10 years after diagnosis (Figure 2B).

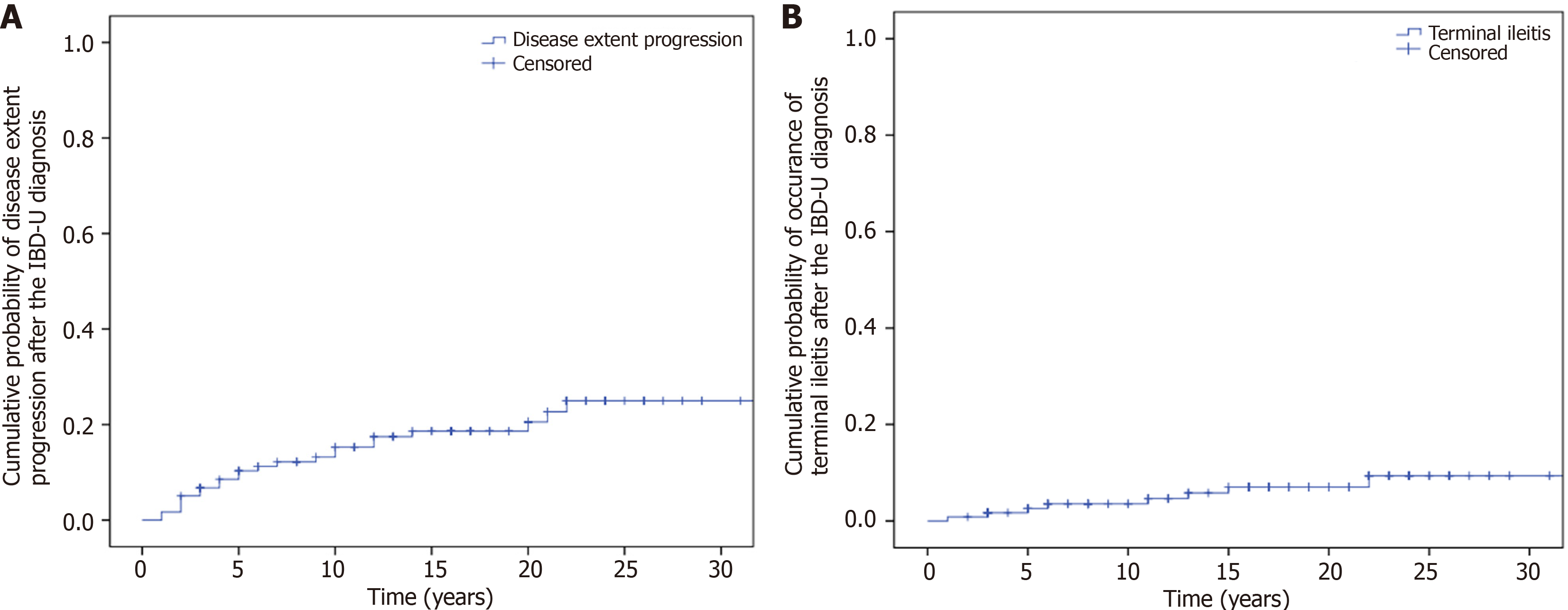

Colonic extent progression was observed in 19.3% (23/119) of the patients during the total follow-up. Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that the probability of progression of disease extent in the colon during follow-up was 6.7% (SD: 2.3) at 3 years, 10.3% (SD: 2.8) at 5 years and 15.3% (SD: 3.4) at 10 years (Figure 3A).

Six-point seven percent (8/119) of the patients developed terminal ileitis during follow-up. The probability of developing terminal ileitis was 2.6% (SD: 1.5) at 5 years and 3.5% (SD: 1.7) at 10 years (Figure 3B).

Perianal disease developed in 5% (n = 6/119) of all patients during the total follow-up. Stenosing disease developed in 10.1% (12/119), while penetrating disease (internal fistulas or abscess) developed in 1.7% (2/119) of the patients. Reclassification to CD was carried out in 18.5% (22/119) of the patients.

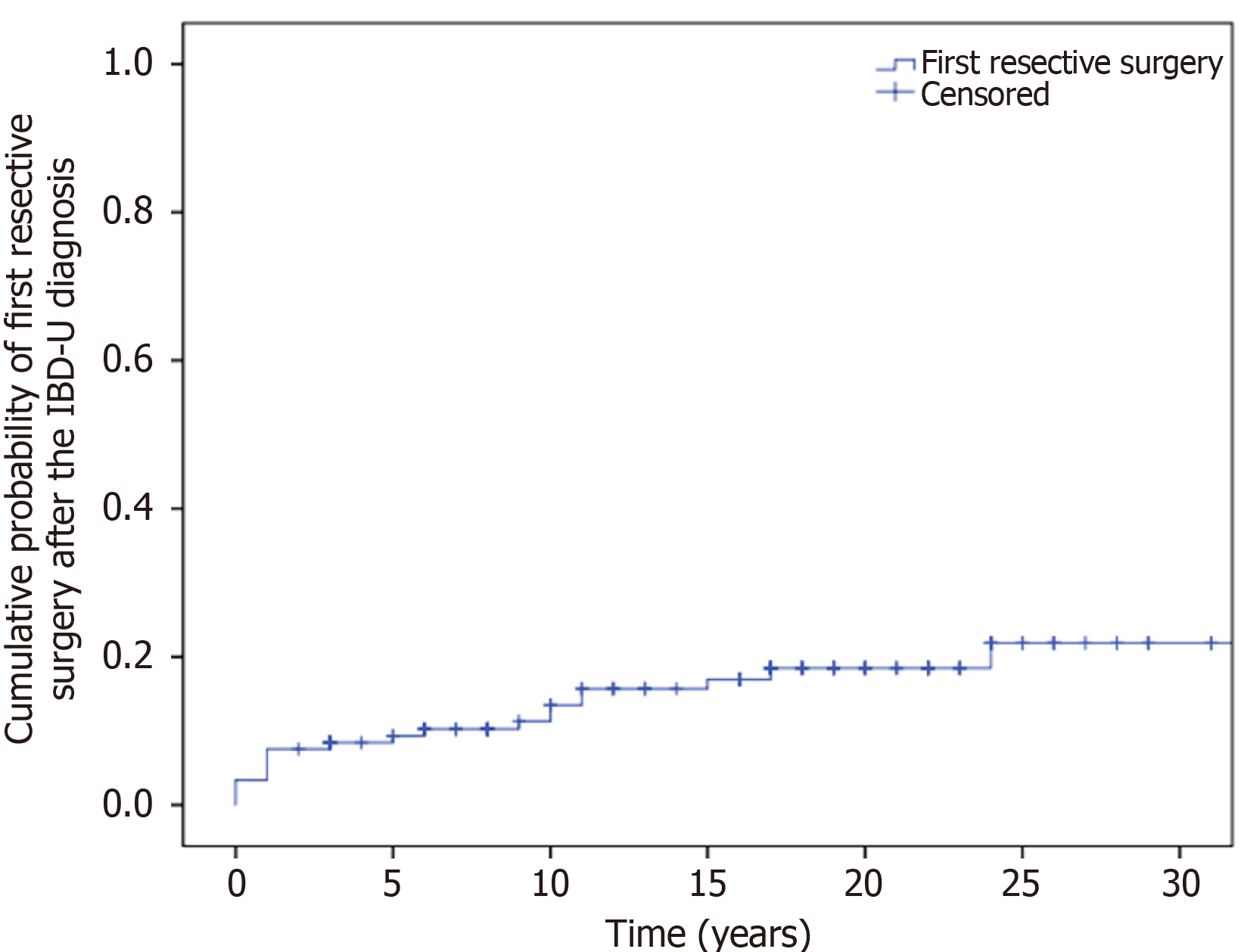

The overall resective surgery rate was 16.8% at the end of follow-up (Table 2). Segment resection was performed in 5.0% of the patients, and a high proportion of patients (11.8%) underwent subtotal- or total colectomy. The cumulative probability of resective surgery was 7.6% (SD: 2.4) at 1 year, 9.3% (SD: 2.7) at 5 years, 13.5% (SD: 3.3) at 10 years, and 18.5% (SD: 3.9) at 20 years (Figure 4).

| Factor variable | Multivariate HR | 95%CI | P valve |

| Male gender | 1.95 | 0.77-4.93 | 0.161 |

| Smoking history | 1.97 | 0.68-5.76 | 0.213 |

| Continuous vs remitting disease activity | 4.58 | 1.61-13.02 | 0.004 |

| Anemia | 4.17 | 1.17-14.89 | 0.028 |

| ‘CD-like’ vs ‘UC-like’ classification upon endoscopy | 1.24 | 0.41-3.73 | 0.705 |

| Reclassification to CD | 7.02 | 2.02-24.39 | 0.002 |

A Cox-regression multivariate analysis was carried out to identify predictive factors for resective surgery. Continuous disease activity, (HR 4.58; 95%CI: 1.61-13.02; P = 0.004), anemia (HR 4.17; 95%CI: 1.17-14.89; P = 0.028) and reclassification to CD (HR 7.02; 95%CI: 2.02-24.39; P = 0.002) were predictors of first resective surgery in IBD-U patients.

In our recent studies, we analyzed the natural history of CD and UC using four decades of data from a well-established, prospective population-based inception cohort[15]. In this study, 4.89% of patients with IBD were initially diagnosed with IBD-U. This is the first comprehensive report on the prevalence and long disease evolution and course of IBD-U patients from Eastern Europe.

There are only a few reports on the prevalence and disease course in IBD-U patients worldwide. The frequency of IBD-U at diagnosis varies between 3% and 9% in these studies. Data were recently reported by the IBSEN and Epi-IBD groups. During the IBSEN Study Group registration period, 843 cases of IBD were identified, including 40 patients with IBD-U (4.7%)[16]. This finding aligns closely with the results of our study.

In the Epi-IBD study, 112 of 1289 IBD patients (9%) were diagnosed with IBD-U[17]. In a separate population-based study conducted in France, a total of 480 patients were initially diagnosed with IBD-U, accounting for 3.6% of all incident IBD cases recorded in the registry between 1988 and 2014[18]. In the newly established 2025 Epi-IBD cohort, a total of 129 patients diagnosed with IBD-U were enrolled across 22 participating centers, representing 8.5% of the overall study population. In line with these values, 4.9% of the total IBD cohort and 8.7% of the UC patients were diagnosed with IBD-U in the present cohort.

The incidence of IBD-U exhibited a marked increase over the observed period; however, drawing definitive conclusions remains challenging. The recognition and classification of IBD-U as a distinct entity became more widespread in clinical practice in later years[19]. Multiple studies have investigated the clinical course of IBD-U. Data confirm that patients initially diagnosed with IBD-U may have varying disease trajectories, with some eventually being reclassified as CD or UC. In contrast, others maintain the IBD-U classification over time.

In the IBSEN study after a five-year follow-up, 17 patients (42.5%) were reclassified as having UC, 5 (12.5%) as having CD, and 9 (22.5%) were determined to have non-IBD conditions[16]. Burisch et al[17], during follow-up, reclassified 28 patients' diagnoses (25%) to either UC (20, 71%) or CD (8, 29%) after a median period of six months. In the 2025 Epi-IBD cohort, over a 10-year follow-up period, 32% (n = 41/129) of patients initially diagnosed with IBD-U were reclassified as either CD (n = 16) or UC (n = 25). The cumulative rates of diagnostic reclassification at 1, 5, and 10 years were 19%, 26%, and 32%, respectively.

In the French study[18] conducted between 1988 and 2014, the cumulative probability of reclassification among patients initially diagnosed with IBD-U was 17% at 1 year, 41% at 5 years, and 54% at 10 years. Specifically, reclassification to UC was 10% at 1 year, 22% at 5 years, and 30% at 10 years, while the corresponding probabilities for reclassification to CD were 5%, 13%, and 18%. In contrast, in the present study, 18.5% of patients were reclassified as having CD; however, UC like IBD-U patients were not reclassified since the endoscopic appearance of the disease may change after initiating therapy. However, most of these patients were treated as having UC.

In these previous studies, a considerable proportion of patients were ultimately reclassified as having UC, aligning with the findings observed in our cohort. In the majority of our cases (56.3%), extensive colonic involvement was observed at diagnosis, indicating a severe disease onset. Additionally, disease progression in terms of colonic involvement was substantial, with an estimated increase of 10.3% (SE: 2.8) at five years. In comparison, data from a European population-based inception cohort demonstrated that 15% of patients with UC progressed to extensive colitis within the first five years of follow-up[20]. In the Epi-IBD study, patients initially diagnosed with IBD-U who were later reclassified as having UC, seven individuals (35%) exhibited an increase in disease extent during the follow-up. One patient (14%) with an initial diagnosis of proctitis and three patients (43%) with left-sided colitis progressed to extensive colitis. Additionally, three patients (43%) initially presenting with proctitis demonstrated progression to left-sided colitis.

The evidence regarding the optimal medical management of IBD-U remains limited due to the absence of large-scale, randomized prospective treatment trials. Consequently, individuals with IBD-U are generally managed according to treatment protocols established for UC or CD, with therapeutic decisions guided by clinical disease characteristics, severity, as well as the extent and severity of endoscopic and histopathological findings[6]. The range of conventional therapies previously investigated for the management of IBD-U includes corticosteroids, thiopurines, aminosalicylates, biologic agents, and small-molecule therapies[21].

In the Epi-IBD study[17], treatment pattern follows the above; most patients (96%) received 5-ASA, while 10% of the patients received biologicals. Biological therapies were used in 13% of patients over the 10-year follow-up in the 2025 Epi-IBD cohort. In the present study, the treatment pattern was different from the above. and probably reflected an overall higher disease severity in our patients. The rate of biological therapy use was as high as 19%, which is higher than typically observed in UC patients and more comparable to treatment patterns seen in CD patients, indicating a more aggressive disease course requiring advanced therapeutic interventions[15,22]. Until 2010, the prescription regulation of advanced therapies was strict in Hungary[15]. Of note, we identified treatment step as an indicator for overall disease severity in our earlier studies. Thus, these data may help clinicians in their management and treatment decisions, when they face IBD-U patients in their everyday practice.

In the Epi-IBD study[17], the distribution of disease phenotypes within that group showed predominantly colonic involvement (87%), with proctitis accounting for 32% and extensive colitis for 23%. In contrast, the present study observed a lower prevalence of proctitis (7.6%) and a higher proportion of patients with extensive colonic involvement (pancolitis), reported at 56.3%.

Surgical intervention rates were similar to the Epi IBD study[17], with 7% of patients undergoing surgery. However, the resective surgery rate in our study was 16.8% over time, with a high colectomy rate and less frequent segmental resections, suggesting again a more severe patient phenotype in our patient population.

One of the key strengths of the present study is that it represents a large prospective population-based cohort with long-term follow-up of IBD patients within a well-defined cohort region, which is rare in IBD-U literature. This comprehensive design allowed for the evaluation of temporal trends in long-term disease outcomes. We employed strict and consistent diagnostic criteria, ensuring appropriate case ascertainment, and utilized a centralized data collection system with standardized forms that were regularly updated throughout the follow-up period. Patient enrollment was consecutive and unselected, enhancing the generalizability of our findings. Additionally, case validation and data collection were overseen by the same lead IBD specialist gastroenterologist throughout the entire observation period, ensuring consistency in assessment and data integrity.

A limitation of our study is that the definition of IBD-U evolved dynamically over the observation period although in the present cohort the same definition was used throughout the study period. However, of note, in our study the IBD-U definition was a pragmatical diagnosis based on the presence of both UC and CD features in colonic IBD patients and the main IBD clinicians remained unchanged over the duration of the study, which provides reliability to our case ascertainment. We also did not aim to reclassify UC-like IBD-U patients to UC for multiple reasons. It is well known that after the start of therapy, the endoscopic presentation of UC may change, may even become patchy during the healing phase (or due to topical therapy). Many patients were in clinical (endoscopic healing) remission for a long period, thus reclassification would not be possible.

Moreover, repeated endoscopy/histological evaluations were not systematically available in all patients during flare periods, and histological results are not necessarily diagnostic in differentiating CD from UC. In contrast, we made every effort to reclassify patients to CD, if the clinical characteristics of the disease changed during follow-up, and suggested the presence of CD.

In conclusion, the incidence of IBD-U has dynamically increased over the past decades in the present population based cohort, along with the increased incidence of UC and CD. Our findings indicate that IBD-U can present as a severe disease phenotype characterized by extensive colonic involvement with a higher need for biological therapy, and increased need for resective surgery. These observations highlight that the disease course is not necessarily benign in IBD-U patients. Furthermore, approximately one fifth of patients were diagnosed with CD during the follow-up. In view of the scarcity of published data, the present paper provides important additional insight on the global burden of IBD-U and helps clinicians to better understand IBD-U patients’ clinical path, their management and treatment decisions in everyday practice.

| 1. | Dignass A, Eliakim R, Magro F, Maaser C, Chowers Y, Geboes K, Mantzaris G, Reinisch W, Colombel JF, Vermeire S, Travis S, Lindsay JO, Van Assche G. Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis part 1: definitions and diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:965-990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 602] [Cited by in RCA: 642] [Article Influence: 49.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Magro F, Gionchetti P, Eliakim R, Ardizzone S, Armuzzi A, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Burisch J, Gecse KB, Hart AL, Hindryckx P, Langner C, Limdi JK, Pellino G, Zagórowicz E, Raine T, Harbord M, Rieder F; European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation [ECCO]. Third European Evidence-based Consensus on Diagnosis and Management of Ulcerative Colitis. Part 1: Definitions, Diagnosis, Extra-intestinal Manifestations, Pregnancy, Cancer Surveillance, Surgery, and Ileo-anal Pouch Disorders. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:649-670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1446] [Cited by in RCA: 1299] [Article Influence: 162.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Shao Y, Zhao Y, Lv H, Yan P, Yang H, Li J, Li J, Qian J. Clinical features of inflammatory bowel disease unclassified: a case-control study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024;24:105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kent TH, Ammon RK, DenBesten L. Differentiation of ulcerative colitis and regional enteritis of colon. Arch Pathol. 1970;89:20-29. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55:749-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1970] [Cited by in RCA: 2354] [Article Influence: 123.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 6. | Geboes K, De Hertogh G. Indeterminate colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2003;9:324-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Prenzel F, Uhlig HH. Frequency of indeterminate colitis in children and adults with IBD - a metaanalysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2009;3:277-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Burakoff R. Indeterminate colitis: clinical spectrum of disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:S41-S43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Winter DA, Karolewska-Bochenek K, Lazowska-Przeorek I, Lionetti P, Mearin ML, Chong SK, Roma-Giannikou E, Maly J, Kolho KL, Shaoul R, Staiano A, Damen GM, de Meij T, Hendriks D, George EK, Turner D, Escher JC; Paediatric IBD Porto Group of ESPGHAN. Pediatric IBD-unclassified Is Less Common than Previously Reported; Results of an 8-Year Audit of the EUROKIDS Registry. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:2145-2153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nuij VJ, Zelinkova Z, Rijk MC, Beukers R, Ouwendijk RJ, Quispel R, van Tilburg AJ, Tang TJ, Smalbraak H, Bruin KF, Lindenburg F, Peyrin-Biroulet L, van der Woude CJ; Dutch Delta IBD Group. Phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease at diagnosis in the Netherlands: a population-based inception cohort study (the Delta Cohort). Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:2215-2222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wewer MD, Lophaven S, Lakatos PL, Gonczi L, Salupere R, Kievit HAL, Nielsen KR, Midjord J, Domislovic V, Krznarić Ž, Pedersen N, Kjeldsen J, Halfvarson J, Sebastian S, Goldis A, Arebi N, Oksanen P, Neuman A, Andersen V, Katsanos KH, Koukoudis A, Turcan S, Ellul P, Kupcinskas J, Kiudelis G, Fumery M, Kaimakliotis IP, D’inca R, Lombardini S, Hernandez V, Fernandez A, Langholz E, Munkholm P, Burisch J; Epi-IBD group. P1258 Disease course of inflammatory bowel disease unclassified during the first ten years following diagnosis: A prospective European population-based inception cohort - the Epi-IBD cohort. J Crohns Colitis. 2025;19:i2275-i2276. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Hungarian Central Statistical Office. Population Census 2011. 2011. [cited 23 July 2025]. Available from: https://www.ksh.hu/nepszamlalas/tablak_teruleti_19. |

| 13. | Lennard-Jones JE. Classification of inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1989;170:2-6; discussion 16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1396] [Cited by in RCA: 1446] [Article Influence: 40.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Munkholm P. Crohn's disease--occurrence, course and prognosis. An epidemiologic cohort-study. Dan Med Bull. 1997;44:287-302. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Kurti Z, Gonczi L, Lakatos L, Golovics PA, Pandur T, David G, Erdelyi Z, Szita I, Lakatos PL. Epidemiology, Treatment Strategy, Natural Disease Course and Surgical Outcomes of Patients with Ulcerative Colitis in Western Hungary - A Population-based Study Between 2007 and 2018: Data from the Veszprem County Cohort. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:352-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Henriksen M, Jahnsen J, Lygren I, Sauar J, Schulz T, Stray N, Vatn MH, Moum B; Ibsen Study Group. Change of diagnosis during the first five years after onset of inflammatory bowel disease: results of a prospective follow-up study (the IBSEN Study). Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:1037-1043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Burisch J, Zammit SC, Ellul P, Turcan S, Duricova D, Bortlik M, Andersen KW, Andersen V, Kaimakliotis IP, Fumery M, Gower-Rousseau C, Girardin G, Valpiani D, Goldis A, Brinar M, Čuković-Čavka S, Oksanen P, Collin P, Barros L, Magro F, Misra R, Arebi N, Eriksson C, Halfvarson J, Kievit HAL, Pedersen N, Kjeldsen J, Myers S, Sebastian S, Katsanos KH, Christodoulou DK, Midjord J, Nielsen KR, Kiudelis G, Kupcinskas L, Nikulina I, Belousova E, Schwartz D, Odes S, Salupere R, Carmona A, Pineda JR, Vegh Z, Lakatos PL, Langholz E, Munkholm P; Epi-IBD group. Disease course of inflammatory bowel disease unclassified in a European population-based inception cohort: An Epi-IBD study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:996-1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jougon J, Leroyer A, Wils P, Guillon N, Sarter H, Gower-rousseau C, Savoye G, Turck D, Fumery M, Ley D. P876 Disease course of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Unclassified in adult patients : a population-based study (1988-2014). J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:i995-i995. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Hammer T, Nielsen KR, Munkholm P, Burisch J, Lynge E. The Faroese IBD Study: Incidence of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Across 54 Years of Population-based Data. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:934-942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Burisch J, Katsanos KH, Christodoulou DK, Barros L, Magro F, Pedersen N, Kjeldsen J, Vegh Z, Lakatos PL, Eriksson C, Halfvarson J, Fumery M, Gower-Rousseau C, Brinar M, Cukovic-Cavka S, Nikulina I, Belousova E, Myers S, Sebastian S, Kiudelis G, Kupcinskas L, Schwartz D, Odes S, Kaimakliotis IP, Valpiani D, D'Incà R, Salupere R, Chetcuti Zammit S, Ellul P, Duricova D, Bortlik M, Goldis A, Kievit HAL, Toca A, Turcan S, Midjord J, Nielsen KR, Andersen KW, Andersen V, Misra R, Arebi N, Oksanen P, Collin P, de Castro L, Hernandez V, Langholz E, Munkholm P; Epi-IBD Group. Natural Disease Course of Ulcerative Colitis During the First Five Years of Follow-up in a European Population-based Inception Cohort-An Epi-IBD Study. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:198-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Venkateswaran N, Weismiller S, Clarke K. Indeterminate Colitis - Update on Treatment Options. J Inflamm Res. 2021;14:6383-6395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rönnblom A, Holmström T, Karlbom U, Tanghöj H, Thörn M, Sjöberg D. Clinical course of Crohn's disease during the first 5 years. Results from a population-based cohort in Sweden (ICURE) diagnosed 2005-2009. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:81-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |