Published online Jul 28, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i28.108926

Revised: June 12, 2025

Accepted: July 7, 2025

Published online: July 28, 2025

Processing time: 85 Days and 17.5 Hours

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a severe condition, and abdominal effusion is a signifi

To assess the correlation between ascites characteristics and clinical prognosis in AP patients by comparing color depth and turbidity of early ascites.

This study included 667 AP patients with ascites, categorized by color and tur

AP patients with ascites exhibited higher scores of scoring systems (such as Bedside index for severity in AP, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Examination II, etc.) and increased complications and mortality rates (all P < 0.05) compared to those without ascites. A linear association was observed between ascites color depth and turbidity and the incidence of OF, pancreatic necrosis, IPN, and mortality (P < 0.05). LDH in ascites demonstrated high accuracy in predicting ACS and intra-abdominal hemorrhage, with areas under the ROC curve of 0.77 and 0.79, respectively.

Early in AP, ascites correlates with OF, IPN, and mortality, showing linear associations with color depth and turbidity. Ascitic LDH reliably predicts ACS and intra-abdominal hemorrhage in AP patients.

Core Tip: This study establishes a correlation between the characteristics of ascites, including color depth and turbidity, and the clinical prognosis of acute pancreatitis (AP) patients. We demonstrate that lactate dehydrogenase levels in ascites can accurately predict the development of abdominal compartment syndrome and intra-abdominal hemorrhage in AP patients. This research provides novel insights into the utility of ascites characteristics as prognostic indicators in AP, potentially aiding in the early identification of patients at higher risk for severe complications and mortality.

- Citation: Rao JW, Li JR, Wu Y, Lai TM, Zhou ZG, Gong Y, Xia Y, Luo LY, Xia L, Cai WH, Huang W, Zhu Y, He WH. Ascites characteristics in acute pancreatitis: A prognostic indicator of organ failure and mortality. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(28): 108926

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i28/108926.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i28.108926

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a prevalent and potentially lethal digestive disorder, with an overall mortality rate of 2.7%, which has seen only marginal improvements despite advancements in therapeutic strategies. Approximately 10%-20% of patients with AP develop severe AP (SAP), a condition associated with a significantly higher mortality rate, estimated at around 30%[1]. Timely assessment of organ function and early identification of SAP are paramount for initiating aggre

The pathogenesis of AP, triggered by diverse etiologies, involves pancreatic cell injury that leads to the release of inflammatory mediators and cytokines. This results in local and systemic inflammatory responses, increased capillary permeability, and subsequent fluid extravasation[5]. Additionally, albumin consumption and mechanical exudation during AP diminish colloidal osmotic pressure in blood vessels, promoting ascites formation. Furthermore, pancreatic necrosis, peripancreatic fat necrosis, and pancreatic duct rupture contribute to the development of pancreatic ascites, which is frequently observed in the early stages of AP.

Pancreatic ascites, characterized by its richness in trypsin, pancreatic lipase, unsaturated fatty acids, and cytokines, introduces toxic components into the circulation through lymphatic vessels. These components are principal contributors to the development of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MOF) and abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) in the early stages of SAP[6,7].

Current research on pancreatitis-associated ascites, both domestically and internationally, predominantly focuses on chronic pancreatitis, with relatively fewer studies addressing ascites in AP. Existing studies demonstrate that patients with SAP have a higher incidence of ascites, with most developing mild to moderate ascites during the early disease course[8]. Recent studies have highlighted that AP patients with ascites have a significantly higher incidence of organ failure (OF) and mortality compared to those without ascites[9]. However, the relationship between the characteristics of ascites and clinical outcomes has not been thoroughly investigated. Observing variations in the color depth and turbidity of ascites in clinical practice, we hypothesize that these characteristics may correlate with the severity of AP. To explore this hypothesis, we conducted a study to investigate the correlation between ascites characteristics and the severity and clinical outcomes of AP, utilizing a prospectively maintained AP database.

We utilized a prospectively maintained database of patients admitted with AP to The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University from July 2005 to December 2019. The Ethics Committee of the hospital approved the use of this database. The database encompassed a comprehensive set of patient data, including demographics, aetiology, medical history, laboratory findings, imaging results, AP severity, hospital stay duration, clinical scores (Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome, APACHE II), and clinical outcomes regarding OF and mortality. All AP patients received standard treatment in accordance with current guidelines, which involved fasting, gastrointestinal decompression, fluid resusci

Inclusion criteria: (1) Diagnosis of AP; (2) Age between 18 years and 85 years; (3) Disease duration of ≤ 7 days; (4) Pre

Exclusion criteria: (1) Chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic tumours, and pancreatic cysts; (2) Cirrhosis, non-pancreatic perito

AP was diagnosed based on the revised Atlanta classification[1], requiring two or more of the following three criteria: (1) Imaging [ultrasound or computed tomography (CT)] indicative of AP; (2) Presence of acute epigastric pain; and (3) Serum enzyme levels more than three times the upper limit of normal. Pleural effusion was diagnosed using imaging exami

AP severity was classified as follows[1]: (1) Mild AP (MAP) indicated no local or systemic complications and no OF; (2) Moderately SAP (MSAP) indicated transient OF lasting less than 48 hours, either alone or with local or systemic compli

Ascites collection and analysis were performed within seven days of disease onset, identified either through ultrasound-detected free fluid or diagnostic paracentesis performed due to abdominal distension. Clinicians collected 5-10 mL of ascites from patients in test tubes, and the samples were promptly analyzed by hospital staff for color classification. Ascites were categorized into three distinct groups: (1) Yellow clear; (2) Yellow turbid; and (3) Red brown. Subsequent cytological and biochemical analyses were conducted to determine ascites components, including total protein, amylase, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and other relevant factors.

Statistical analysis was performed using Excel 2013 and Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (version 23.0). Data that were normally distributed and exhibited equal variances were presented as the mean ± SD, and mean values were compared using a Student's t-test. One-way analysis of variance was used to analyze multiple sets of data. Non-normally distributed data with inconsistent variability were expressed as the median (interquartile range), and group differences were analyzed using the rank sum test. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, and the χ2 test was used to assess differences among categorical variables. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to evaluate the predictive accuracy of ascites parameters for ACS and abdominal bleeding. The Jorden index was employed to measure the sensitivity and specificity of these predictions. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

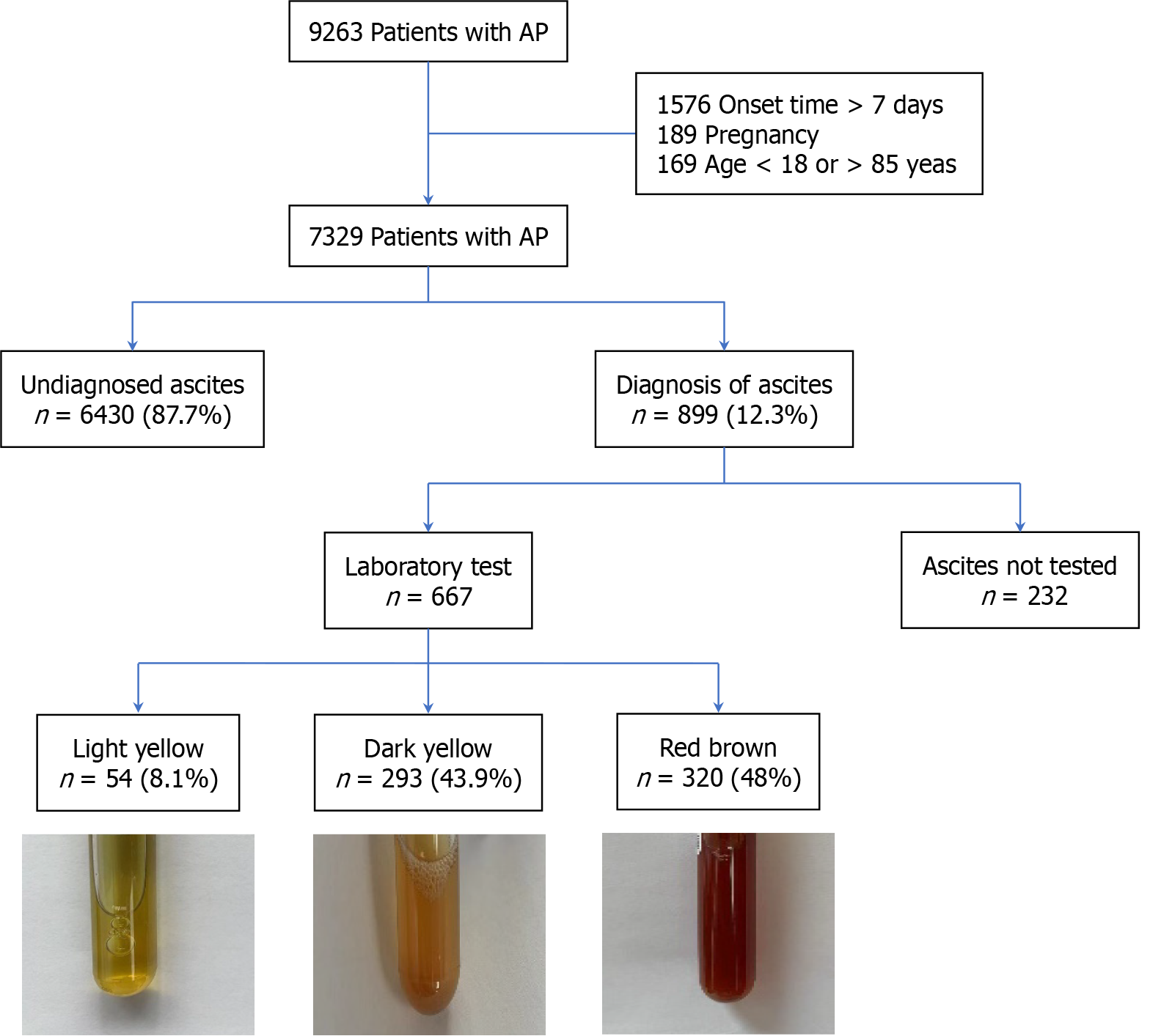

Between July 2005 and December 2019, a cohort of 9263 individuals was admitted to The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University with a diagnosis of AP. The study population was refined by excluding patients with a disease duration exceeding 7 days (n = 1576), those afflicted with chronic pancreatitis, liver cirrhosis, and other comorbidities known to induce ascites (n = 41), and pregnant women (n = 189). This exclusion process yielded a study cohort of 7329 AP patients. Within this group, 6430 patients (87.7%) were either devoid of ascites or had incomplete datasets, resulting in a subset of 899 patients who were confirmed to have ascites. Ascites samples from 667 of these patients were examined in the laboratory. These patients were subsequently categorized into three distinct groups based on the color and characteristics of their ascites: (1) Yellow clear transparent ascites (n = 54); (2) Yellow turbid ascites (n = 293); and (3) Red brown ascites (n = 320). Figure 1 presents a flow chart delineating the patient selection process and the stratification of ascites.

The clinical characteristics of patients with and without ascites are summarized in Table 1. The study population com

| Characteristics | No ascites (n = 6430) | Ascites (n = 899) | P value |

| Gender (male) | 3702 (57.6) | 540 (60.1) | 0.01 |

| Age (years) | 50 (40-63) | 50 (41-63) | 0.64 |

| Admission day | 2 (1-4) | 2 (1-3) | 0.1 |

| Etiology | |||

| Alcoholic | 498 (7.7) | 102 (11.3) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 1584 (24.6) | 278 (30.9) | < 0.001 |

| Biliary | 3686 (57.3) | 452 (50.3) | < 0.001 |

| Others1 | 178 (2.8) | 10 (1.1) | 0.004 |

| Idiopathic | 528 (8.2) | 57 (6.3) | 0.061 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 1057 (16.4) | 193 (21.5) | < 0.001 |

| Coronary heart disease | 96 (1.5) | 17 (1.9) | 0.364 |

| Heart failure | 23 (0.4) | 6 (0.7) | 0.166 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 49 (0.8) | 15 (1.7) | 0.006 |

| Diabetes | 556 (8.6) | 96 (10.7) | 0.045 |

| Interventions | |||

| Ventilator ventilation | 208 (3.2) | 296 (32.9) | 0.009 |

| Early termination of disease | 41 (0.6) | 42 (4.7) | < 0.001 |

| Percutaneous catheter drainage | 70 (1.1) | 191 (21.2) | < 0.001 |

| Endoscopic debridement | 23 (0.4) | 75 (8.3) | < 0.001 |

| Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography | 1381 (21.5) | 121 (13.5) | < 0.001 |

| Complications | |||

| Abdominal compartment syndrome | 13 (0.2) | 80 (8.9) | < 0.001 |

| Abdominal bleeding | 11 (0.2) | 40 (4.4) | < 0.001 |

| Septicemia | 46 (0.7) | 119 (13.2) | < 0.001 |

| Intestinal fistula | 6 (0.1) | 24 (2.7) | < 0.001 |

| Transient OF | 1421 (22.1) | 695 (77.3) | < 0.001 |

| Transient respiratory failure | 557 (8.7) | 125 (13.9) | < 0.001 |

| Transient renal failure | 94 (1.5) | 62 (6.9) | < 0.001 |

| Transient circulatory failure | 42 (0.7) | 25 (2.8) | < 0.001 |

| Persistent OF | 824 (12.8) | 568 (63.2) | < 0.001 |

| Persistent respiratory failure | 762 (11.9) | 542 (60.3) | < 0.001 |

| Persistent kidney failure | 133 (2.1) | 184 (20.5) | < 0.001 |

| Persistent circulatory failure | 79 (1.2) | 163 (18.1) | < 0.001 |

| Necrotizing pancreatitis | 1056 (16.4) | 512 (57.0) | < 0.001 |

| Infected pancreatic necrosis | 86 (1.3) | 189 (21.0) | < 0.001 |

| Clinical Tab Score for Imaging (week 1) | 2 (1-3) | 4 (3-6) | < 0.001 |

| Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome Score (day 1) | 1 (0-2) | 2 (2-3) | < 0.001 |

| Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II Score (day 1) | 6 (4-9) | 9 (6-13) | < 0.001 |

| Mild acute pancreatitis | 3172 (49.3) | 50 (5.6) | < 0.001 |

| Moderately severe acute pancreatitis | 2438 (37.9) | 281 (31.3) | < 0.001 |

| Severe acute pancreatitis | 820 (12.8) | 568 (63.2) | < 0.001 |

| Death | 47 (0.7) | 80 (9.0) | < 0.001 |

| Hospital days | 8 (5-11) | 17 (10-28) | < 0.001 |

Out of 899 patients with ascites, 65.9% underwent PCD, and 10.6% underwent abdominal lavage. Ascites samples from 667 patients were analyzed, with 54 classified as yellow clear, 293 as yellow turbid, and 320 as red brown. Laboratory data for these patients are detailed in Supplementary Table 1. The bacterial detection rate in ascites was 9.7%, and the average cell count was 252 cells/mm³ (range 26-4000 cells/mm³), with 85% (range 9%-92%) being neutrophils. The median total protein level in ascites was 34.78 g/L (range 23.92-40.98 g/L), the amylase level was 572 U/L (range: 98.5-2191.5 U/L), and the LDH level was 1192 U/L (range: 297-2654.2 U/L).

The highest cell count was observed in yellow turbid ascites, averaging 400 cells/mm³ (range: 28-3900 cells/mm³), while the highest levels of amylase (825 U/L) and total protein (36.4 g/L) were found in red brown ascites (all P < 0.05). Notably, ascitic LDH levels increased progressively with darker ascites color [115 U/L (range: 29-790 U/L) vs 1138 U/L (range: 251-2055 U/L) vs 1573 U/L (range: 539-3377 U/L)], with a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001) as shown in Table 2.

| Indicators | Yellow clear ascites (n = 54) | Yellow cloudy ascites (n = 293) | Red brown ascites | P value |

| Gender (male) | 32 (59.3) | 183 (62.5) | 187 (58.4) | 0.589 |

| Admission day after onset | 3 (1-3) | 2 (1-4) | 2 (1-3) | 0.156 |

| Etiology | ||||

| Alcoholic | 5 (9.3) | 41 (14.0) | 29 (9.1) | 0.138 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 9 (16.7) | 84 (28.7) | 85 (26.6) | 0.186 |

| Biliary | 32 (59.3) | 134 (45.7) | 161 (50.3) | 0.154 |

| Idiopathic | 2 (3.7) | 27 (9.2) | 34 (10.6) | 0.270 |

| Ascites cell count (cells/mm³) | 55 (12-1000) | 400 (28-3900) | 226 (29-4323) | 0.075 |

| Proportion of neutrophils in ascites (%) | 65 (9-90) | 85 (9-92) | 85 (9-94) | 0.029 |

| Total ascites protein (g/L) | 31.1 (3.6-36.9) | 32.6 (17.4-39.7) | 36.4 (28.8-41.9) | < 0.001 |

| Ascites amylase (U/L) | 35 (11-210) | 596 (78-1897) | 825 (219-2826) | < 0.001 |

| Ascites lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 115 (29-790) | 1138 (251-2055) | 1573 (539-3377) | < 0.001 |

| Positive for ascites bacteria smear | 5 (9.3) | 29 (9.9) | 31 (9.7) | 0.988 |

| Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome Score (day 1) | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) | 3 (2-3) | < 0.001 |

| Bedside Index for Severity in Acute Pancreatitis Score (day 1) | 1 (1-2) | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) | 0.001 |

| Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II Score (day 1) | 8 (5-12) | 9 (5-12) | 10 (7-14) | 0.001 |

| Clinical Tab Score for Imaging (week 1) | 4 (2-5) | 4 (2-6) | 6 (3-8) | < 0.001 |

| Pancreatic necrosis | 20 (37.0) | 131 (44.7) | 209 (65.3) | < 0.001 |

| Infected pancreatic necrosis | 5 (9.3) | 42 (14.3) | 75(23.4) | 0.003 |

| Percutaneous catheter drainage | 3 (5.6) | 42 (14.3) | 73 (22.8) | 0.019 |

| Endoscopic debridement | 2 (3.7) | 10 (3.4) | 33 (10.3) | 0.01 |

| OF | 34 (63.0) | 216 (73.7) | 259 (80.9) | 0.006 |

| Persistent OF | 27 (50.0) | 164 (56.0) | 221 (69.1) | 0.001 |

| Persistent respiratory failure | 26 (48.1) | 158 (53.9) | 211 (65.9) | 0.002 |

| Persistent kidney failure | 4 (7.4) | 37 (12.6) | 97 (30.3) | < 0.001 |

| Persistent circulatory failure | 6 (11.1) | 30 (10.2) | 73 (22.8) | < 0.001 |

| Abdominal compartment syndrome | 2 (3.7) | 14 (4.8) | 41 (12.8) | 0.001 |

| Respiratory infection | 5 (9.3) | 21 (7.2) | 53 (16.6) | 0.001 |

| Blood infection | 5 (9.3) | 32 (10.9) | 68 (21.3) | < 0.001 |

| Mild acute pancreatitis | 10 (18.5) | 20 (6.8) | 1 (0.3) | < 0.001 |

| Moderately severe acute pancreatitis | 17 (31.5) | 108 (36.9) | 98 (30.6) | 0.250 |

| Sever acute pancreatitis | 27 (50.0) | 165 (56.3) | 221 (69.1) | 0.001 |

| Death | 1 (1.9) | 17 (5.8) | 38(11.9) | 0.021 |

| Hospital days | 13 (7-20) | 15 (10-23) | 18 (11-30) | 0.001 |

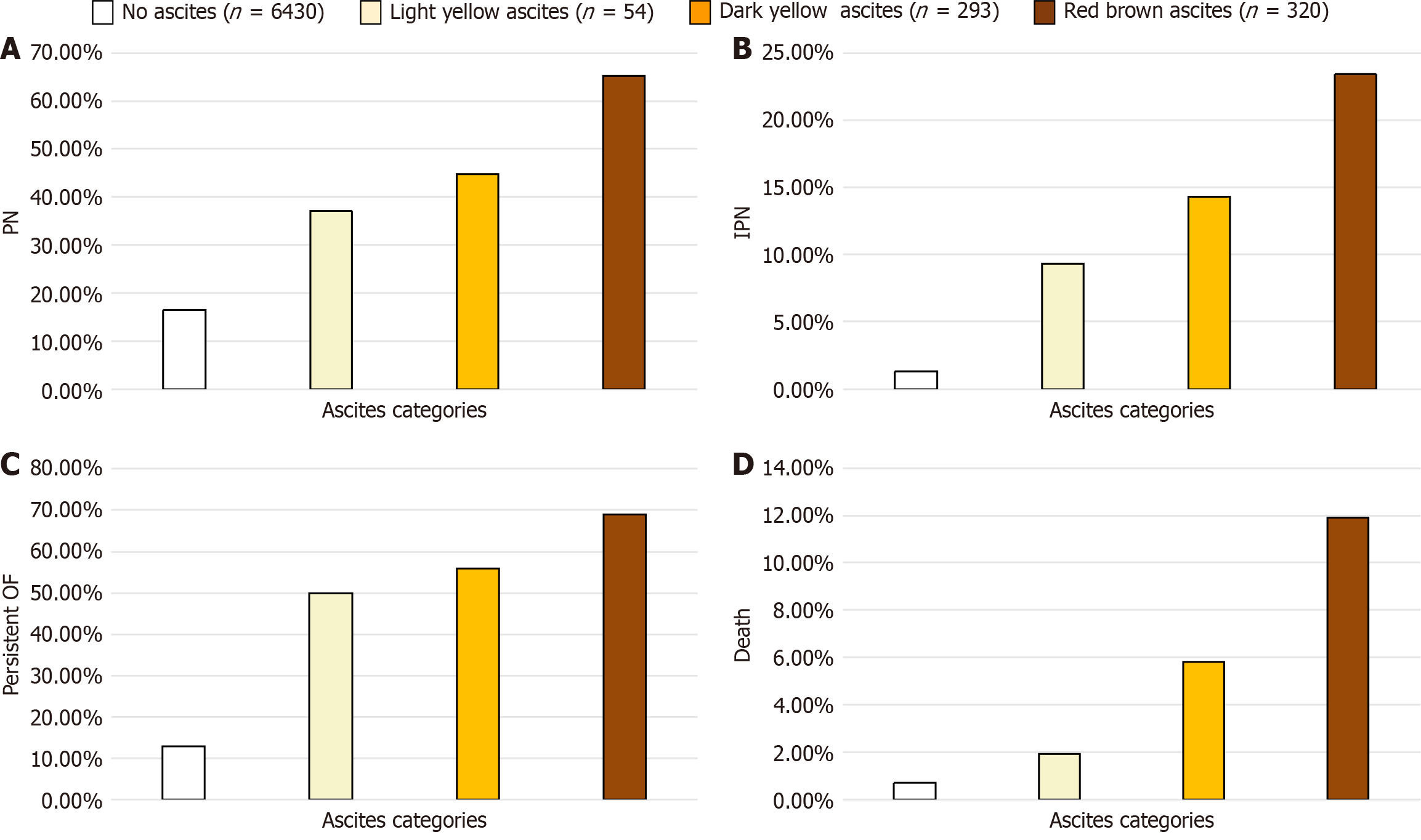

An increase in ascites color depth and turbidity correlated with higher APACHE II and Clinical Tab Score for Imaging scores on week 1 CT scans (all P < 0.001). Concurrently, the incidence of OF (63.0% vs 73.7% vs 80.9%) and persistent OF (50.0% vs 56.0% vs 69.1%) also increased with darker ascites (all P < 0.05) as depicted in Figure 2 and Table 2. Similar trends were observed in the incidence of pancreatic necrosis, IPN, bloodstream infections, ACS, requirement for PCD, need for endoscopic debridement, hospital stay duration and mortality rates in AP patients with ascites.

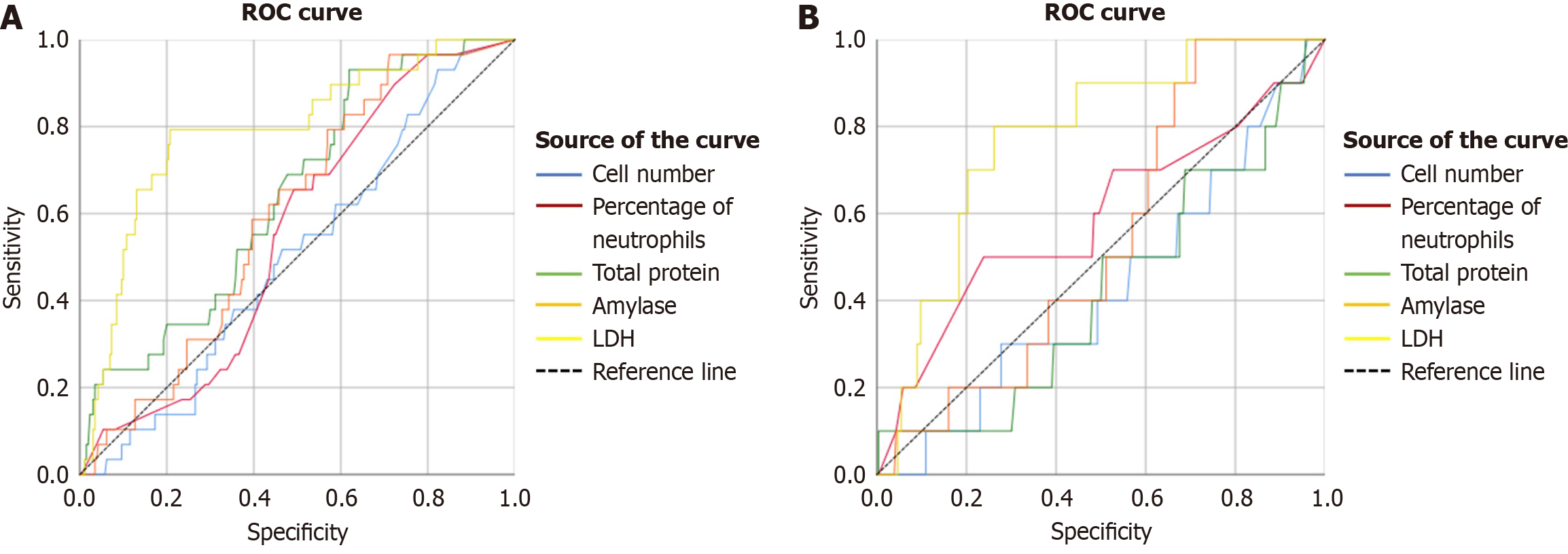

The predictive value of ascites components, including cell count, neutrophil ratio, total protein, amylase, and LDH, for intra-abdominal hemorrhage and ACS in AP patients was assessed using the ROC curve. Only LDH in ascites demon

The present retrospective analysis, leveraging a prospectively compiled database, revealed that patients with AP and ascites exhibited a more severe disease course, prolonged hospital stays, increased incidence of OF, and higher mortality rates compared to AP patients without ascites. The color and turbidity of ascites in the early stages of AP were signifi

Our study identified obvious ascites in only 12.3% of the 7329 AP patients, a proportion that may reflect our focus on early-stage AP with ascites. Ascites amylase levels were found to be significantly elevated at 572 U/L (range: 98.5-2191.5 U/L), with corresponding serum amylase levels at 337 U/L (range: 130-727 U/L), yielding an ascites/serum amylase ratio of 1.70. This ratio, along with the elevated ascites albumin, suggests a pancreatic origin of ascites in these patients, consistent with literature reports indicating that a ruptured pancreatic duct should be suspected when ascites amylase exceeds 100 U/L and the blood/ascites protein ratio is low[8,10]. Furthermore, a higher ascites/blood amylase ratio is indicative of pancreatic duct rupture, whereas a lower ratio suggests inflammatory exudate[11].

Our findings underscored that AP patients with ascites had a higher prevalence of necrotizing pancreatitis and SAP, along with increased incidences of IPN, OF, local and systemic complications, extended hospital stays, and greater mortality. This reinforces the notion that ascites serves as a robust indicator of AP severity and portends a poorer prognosis, aligning with previous research[12,13]. Ascites has also been established as a significant predictor of mortality in AP patients, associated with longer hospitalizations and an increased need for intensive care unit admissions[9].

The colour of ascites in SAP has been correlated with disease severity and patient condition deterioration. In our study, the majority of patients with ascites presented with yellow-colored ascites, which was associated with poorer clinical outcomes. Patients with red and crimson ascites exhibited elevated ascites protein and amylase levels. Ascites contains various bioactive compounds such as lipase, protease, and lysolecithin, which can erode abdominal tissues, including blood vessels and other tissues[14,15]. An animal study on pancreatic ascites indicated that the presence of toxic sub

The presence of ascites in early-stage AP is also associated with the development of ACS[6]. Toxic chemicals in ascites can irritate the bowel and induce intestinal paralysis in AP patients, potentially elevating abdominal pressure. LDH is a notable serum marker in cases of severe abdominal organ injury, such as pancreatic necrosis and blood vessel damage. While there are limited studies on ascites LDH in AP patients, existing research indicates that elevated serum LDH in AP patients is related to severe disease[23]. Our study showed that ascites LDH has a high specificity and sensitivity of 79% in predicting ACS in AP patients[24]. During the acute phase of various diseases, tissue and organ damage leads to elevated LDH levels. The severity of intra-abdominal organ injury, such as pancreatic necrosis with exudation, visceral/vascular damage, or hemoperitoneum. These correlates with more pronounced LDH elevation. These pathological changes also contribute to increased intra-abdominal pressure, which mechanistically explains why LDH serves as a predictive biomarker for ACS. Additionally, LDH in ascites accurately predicted intra-abdominal hemorrhage in this study, likely due to increased LDH reflecting vascular damage and a predisposition to hemorrhage.

This study has several restrictions. Firstly, its retrospective nature may have introduced information bias and con

Our research underscores that AP patients presenting with ascites have a more severe condition and poorer outcomes. The color depth and turbidity of pancreatic ascites are linearly correlated with the incidence of OF, IPN, and mortality. Ascites LDH can accurately predict ACS and intra-abdominal hemorrhage in AP patients.

| 1. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4329] [Article Influence: 360.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (45)] |

| 2. | Whitcomb DC. Clinical practice. Acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2142-2150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 549] [Cited by in RCA: 518] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Talukdar R, Swaroop Vege S. Early management of severe acute pancreatitis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2011;13:123-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | He WH, Zhu Y, Zhu Y, Jin Q, Xu HR, Xion ZJ, Yu M, Xia L, Liu P, Lu NH. Comparison of multifactor scoring systems and single serum markers for the early prediction of the severity of acute pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:1895-1901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lee PJ, Papachristou GI. New insights into acute pancreatitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:479-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 516] [Article Influence: 86.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | De Waele JJ, Leppäniemi AK. Intra-abdominal hypertension in acute pancreatitis. World J Surg. 2009;33:1128-1133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Noel P, Patel K, Durgampudi C, Trivedi RN, de Oliveira C, Crowell MD, Pannala R, Lee K, Brand R, Chennat J, Slivka A, Papachristou GI, Khalid A, Whitcomb DC, DeLany JP, Cline RA, Acharya C, Jaligama D, Murad FM, Yadav D, Navina S, Singh VP. Peripancreatic fat necrosis worsens acute pancreatitis independent of pancreatic necrosis via unsaturated fatty acids increased in human pancreatic necrosis collections. Gut. 2016;65:100-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bush N, Rana SS. Ascites in Acute Pancreatitis: Clinical Implications and Management. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67:1987-1993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Samanta J, Rana A, Dhaka N, Agarwala R, Gupta P, Sinha SK, Gupta V, Yadav TD, Kochhar R. Ascites in acute pancreatitis: not a silent bystander. Pancreatology. 2019;19:646-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Mann SK, Mann NS. Pancreatic Ascites. Am J Gastroenterol. 1979;71:186-192. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Haas LS, Gates LK Jr. The ascites to serum amylase ratio identifies two distinct populations in acute pancreatitis with ascites. Pancreatology. 2002;2:100-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yang E, Nguyen NH, Kwong WT. Abdominal free fluid in acute pancreatitis predicts necrotizing pancreatitis and organ failure. Ann Gastroenterol. 2021;34:872-878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zeng QX, Wu ZH, Huang DL, Huang YS, Zhong HJ. Association Between Ascites and Clinical Findings in Patients with Acute Pancreatitis: A Retrospective Study. Med Sci Monit. 2021;27:e933196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gutierrez PT, Folch-Puy E, Bulbena O, Closa D. Oxidised lipids present in ascitic fluid interfere with the regulation of the macrophages during acute pancreatitis, promoting an exacerbation of the inflammatory response. Gut. 2008;57:642-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Svensson C, Sjödahl R, Lilja I, Ihse I. The role of ascites and phospholipase A2 on peritoneal permeability changes in acute experimental pancreatitis. Int J Pancreatol. 1990;6:71-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Satake K, Koh I, Nishiwaki H, Umeyama K. Toxic products in hemorrhagic ascitic fluid generated during experimental acute hemorrhagic pancreatitis in dogs and a treatment which reduces their effect. Digestion. 1985;32:99-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ueda T, Takeyama Y, Takase K, Hori Y, Kuroda Y, Ho HS. Hematin is one of the cytotoxic factors in pancreatitis-associated ascitic fluid that causes hepatocellular injury. Surgery. 2002;131:66-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | He WH, Xion ZJ, Zhu Y, Xia L, Zhu Y, Liu P, Zeng H, Zheng X, Lei YP, Huang X, Zhu X, Lv NH. Percutaneous Drainage Versus Peritoneal Lavage for Pancreatic Ascites in Severe Acute Pancreatitis: A Prospective Randomized Trial. Pancreas. 2019;48:343-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Souza LJ, Coelho AM, Sampietre SN, Martins JO, Cunha JE, Machado MC. Anti-inflammatory effects of peritoneal lavage in acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2010;39:1180-1184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bielecki JW, Dlugosz J, Pawlicka E, Gabryelewicz A. The effect of pancreatitis associated ascitic fluid on some functions of rat liver mitochondria. A possible mechanism of the damage to the liver in acute pancreatitis. Int J Pancreatol. 1989;5:145-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sun B, Li HL, Gao Y, Xu J, Jiang HC. Analysis and prevention of factors predisposing to infections associated with severe acute pancreatitis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2003;2:303-307. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Heath DI, Wilson C, Gudgeon AM, Jehanli A, Shenkin A, Imrie CW. Trypsinogen activation peptides (TAP) concentrations in the peritoneal fluid of patients with acute pancreatitis and their relation to the presence of histologically confirmed pancreatic necrosis. Gut. 1994;35:1311-1315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Losurdo G, Iannone A, Principi M, Barone M, Ranaldo N, Ierardi E, Di Leo A. Acute pancreatitis in elderly patients: A retrospective evaluation at hospital admission. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;30:88-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cui J, Xiong J, Zhang Y, Peng T, Huang M, Lin Y, Guo Y, Wu H, Wang C. Serum lactate dehydrogenase is predictive of persistent organ failure in acute pancreatitis. J Crit Care. 2017;41:161-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |