Published online Feb 21, 2023. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v29.i7.1219

Peer-review started: September 28, 2022

First decision: December 12, 2022

Revised: December 26, 2022

Accepted: February 13, 2023

Article in press: February 13, 2023

Published online: February 21, 2023

Processing time: 145 Days and 19.9 Hours

Dietary methyl donors might influence DNA methylation during carcinogenesis of colorectal cancer (CRC). However, whether the influence of methyl donor in

To improve the current understanding of the molecular basis of CRC.

A literature search in the Medline database, Reference Citation Analysis (https://www.referencecitationanalysis.com/), and manual reference screening were performed to identify observational studies published from inception to May 2022.

A total of fourteen case-control studies and five cohort studies were identified. These studies included information on dietary methyl donors, dietary components that potentially modulate the bioavailability of methyl groups, genetic variants of methyl metabolizing enzymes, and/or markers of CpG island methylator phenotype and/or microsatellite instability, and their possible inter

Several studies have suggested interactions between methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphisms, methyl donor nutrients (such as folate) and alcohol on CRC risk. Moreover, vitamin B6, niacin, and alcohol may affect CRC risk through not only genetic but also epigenetic regulation. Identification of specific mechanisms in these interactions associated with CRC may assist in developing targeted prevention strategies for individuals at the highest risk of developing CRC.

Core Tip: Dietary methyl donors might influence DNA methylation during the carcinogenesis of colorectal cancer (CRC). However, whether the influence of methyl donor intake is modified by polymorphisms in such epigenetic regulators is still unclear. We conducted a systematic review on this topic to improve the current understanding of the molecular basis of CRC. Several studies have suggested interactions between methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphisms, methyl donor nutrients (such as folate) and alcohol on CRC risk. Moreover, vitamin B6, niacin, and alcohol may affect CRC risk through not only genetic but also epigenetic regulation.

- Citation: Chávez-Hidalgo LP, Martín-Fernández-de-Labastida S, M de Pancorbo M, Arroyo-Izaga M. Influence of methyl donor nutrients as epigenetic regulators in colorectal cancer: A systematic review of observational studies. World J Gastroenterol 2023; 29(7): 1219-1234

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v29/i7/1219.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v29.i7.1219

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most frequent type of cancer and is responsible for the second highest mortality rate in cancer patients worldwide[1]. Although screening for early detection of CRC is effective to help decrease the trends in mortality rates, understanding daily life factors is also important to prevent this type of cancer[2]. The main factors which may help prevent CRC are those associated with diet, lifestyle, and prevention of metabolic diseases[3].

With regards to the dietary component, nutrients associated with one carbon (1C) metabolism [including folate, other B vitamins, methionine (Met), and choline] have been recognized as anticarcinogenic and chemotherapeutic agents in the 1C metabolic network[4]. Folate has shown to play a preventive role in CRC, probably because of its involvement in the processes of DNA methylation and synthesis[5]. Other nutrients, such as Met and vitamins B6 and B12, which interact metabolically with folate in this process, may also influence the risk of CRC[6]. Moreover, in some of those studies, the observed inverse association between folate status and CRC risk was further modified by genetic polymorphisms of the enzymes involved in folate metabolism, most notably methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR).

A common C677T substitution in the MTHFR gene results in a protein with valine instead of alanine, yielding a more thermolabile enzyme with decreased activity[7]. Numerous studies have shown that this variant (TT) is associated with a decreased risk of CRC, but only when folate status is normal or high. MTHFR polymorphism is possibly the best-known gene polymorphism that switches from being a risk factor to a protective one depending on nutrient status. In any case, it is also important to evaluate the joint influence that other polymorphisms in genes involved in folate metabolism might exert. Thus, for example, Met synthase requires vitamin B12, as methylcobalamin, as a cofactor. A variant in this gene, A2756G [in methionine synthase (MTR) gene], has been described and results in the substitution of aspartate by glycine. Some studies have shown that the MTR 2756 GG genotype is associated with a decreased risk of CRC; however, the association with diet is still unclear[8,9].

Another relevant example of a mutation in a polymorphism associated with CRC risk, but not consistent with nutrients, is the case of serine hydroxymethyltransferase, a pyridoxal phosphate (B6)-dependent enzyme, in particular the polymorphism C1420T[10]. An additional relationship between 1C metabolism-related nutrients and CRC risk is related to its influence on DNA methylation. Thus, low folate status or intake is related to a decreasing methylation level[11,12], whereas colonic mucosal DNA methylation increased globally as a result of folate supplementation[13]. A sufficient intake of methyl donors may also prevent aberrant CpG island promoter hypermethylation. The promoter CpG island hypermethylation that characterizes the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) in CRC is common[14]. Moreover, polymorphisms in enzymes involved in folate metabolism may change the potential impact of methyl donor consumption on DNA methylation[15].

According to the molecular subtype, chromosomal instability, and microsatellite instability (MSI) represent the major pathways for CRC[16]. The inactivation of DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes, which are responsible for correcting mismatched bases during DNA replication, results in MSI[17]. Microsatellites are short sequences that are dispersed across the genome and are likely to undergo MMR machinery-induced deletion or insertion. Defects in the MMR machinery are associated with CRC[18] and can be affected by epigenetic alterations and deregulation of methylation[19]. In this sense, the associations between methyl donor nutrient intake and CRC risk have been extensively studied, although evidence on their effect is limited[20]. However, whether they act as effect modifiers against a background of deficient DNA repair capacity is unknown.

Until now, there have been few studies on the influence of methyl group donors as epigenetic regulators in CRC[21]. In the present work, we reviewed previous studies that have investigated this matter to improve the current understanding of the molecular basis of CRC, which could contribute to a better design of future research and to better preventive nutritional management in this type of cancer.

The search terms and search strategy were developed by two researchers. To guide this research, we formulated the following question as the starting point: What is the influence of methyl donor nutrients as epigenetic regulators in CRC? For this purpose, a systematic search in the Medline (through PubMed) database, Reference Citation Analysis (https://www.referencecitationanalysis.com/, an artificial intelligence technology-based open multidisciplinary citation analysis database), and a manual reference screening were performed to identify observational studies published from inception to May 20, 2022. A search for relevant keywords and medical subject heading terms related to dietary methyl donors, dietary components that potentially modulate the bioavailability of methyl groups, genetic variants of methyl-metabolizing enzymes, markers of CIMP and/or MSI, in combination with keywords related to CRC events was conducted.

The search was amplified through citation chaining (forward and backward) of the included studies. Reference lists of all identified articles and other related review articles, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses were hand-searched for additional articles. The present search was developed according to the “PRISMA Statement” guidelines (see the PRISMA checklist) (www.prisma-statement.org). For this review, a protocol was not prepared or registered. The search strategy is detailed as follows: (1) Colorectal neoplasms/exp or [(colorectal* or rect* or anal* or anus or colon* or sigmoid) adj3 (cancer* or carcinoma or tumour* or tumor* or neoplas* or adenoma or adenocarcinoma)], abstract (ab), keyword hearing word (kf), original title (ot), title (ti), text word (tw); (2) (observational or case-control or cohort), ab, kf, ot, ti, tw; (3) (incidence or prevalence or risk or odds ratio or hazard ratio), ab, kf, ot, ti, tw; (4) (one-carbon metabolism-related nutrient* or dietary methyl donor* or alcohol), ab, kf, ot, ti, tw; and (5) [gen* or single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)* or polymorphism* or methyl metabolizing enzyme* or diet–gene interaction* or hypermethylation* or microsatellite instability*], ab, kf, ot, ti, tw.

Two researchers independently screened the titles and abstracts of the articles to identify potentially relevant studies. Studies that passed the title/abstract review were retrieved for full-text review. The inclusion and exclusion criteria and the quality of the study were assessed by two researchers with the use of a data extraction form especially designed for this study.

The inclusion criteria consisted of studies: (1) With an observational design (case-control or cohort); (2) that evaluated the exposure to at least one of the following dietary components (dietary nutrient intake and/or plasma levels): Folate, other B vitamins, Met, choline, betaine, and/or alcohol; (3) that included genotyping analyses of methyl-metabolizing enzymes (MTHFR, MTR, Met synthase reductase), DN methyltransferase 3 b, euchromatin histone methyltransferase 1 and 2, PR domain zinc finger protein 2; (4) CIMP defined by promotor hypermethylation (calcium voltage-gated channel subunit a1 G, insulin-like growth factor 2, neurogenin1, runt-related transcription factor 3, suppressor of cytokine signalling 1), human MutL homolog 1 (hMLH1) hypermethylation; (5) MSI using markers [such as mononucleotide microsatellites with quasi-monomorphic allele length distribution in healthy controls but unstable (Bat-26 and/or Bat-25), NR-21, NR-22, NR-24)]; (6) in which the outcome of interest was CRC, colon, or rectal cancer (studies investigating benign adenomas or polyps were excluded); (7) that provided estimates of the adjusted odds ratios or relative risks or hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI); (8) conducted in humans (≥ 18 years old); and (9) written in English or Spanish.

The following types of publications were excluded: (1) Nonoriginal papers (reviews, commentaries, editorials, or letters); (2) meta-analysis studies; (3) off-topic studies; (4) studies lacking specific CRC data; (5) nonhuman research; (6) studies conducted in children, adolescents, or pregnant women; (7) duplicate publications; and (8) low-quality studies (Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS)[22] < 4 indicating insufficient study quality).

To evaluate the validity of the individual studies, two reviewers worked independently to determine the quality of the included studies based on the use of the NOS for case-control or cohort studies[22]. The maximum score was 9, and a high score (≥ 6) indicated high methodological quality; however, given the lack of studies on the subject under study, it was agreed to select those that had a score equal to or greater than 4. A consensus was reached between the reviewers if there were any discrepancies.

The data extracted for each individual study included the following: Name of the first author, study design, characteristics of the study population (age range or mean age, sex, country), dietary exposure, dietary assessment instrument used, outcomes (including cancer site), comparison, odds ratio or relative risk or hazard ratio (95%CI), adjusted variables, and NOS. For case-control studies, the following additional information was extracted: Number of cases and number of controls. For cohort studies, the following additional information was extracted: Number of participants at baseline, number of CRC cases, and length of follow-up. These variables were judged to be most relevant to the outcome studied. Where multiple estimates for the association of the same outcome were used, the one with the highest number of adjusted variables was extracted. Template data collection forms and data extracted from the included studies will be made available upon request from the corresponding author.

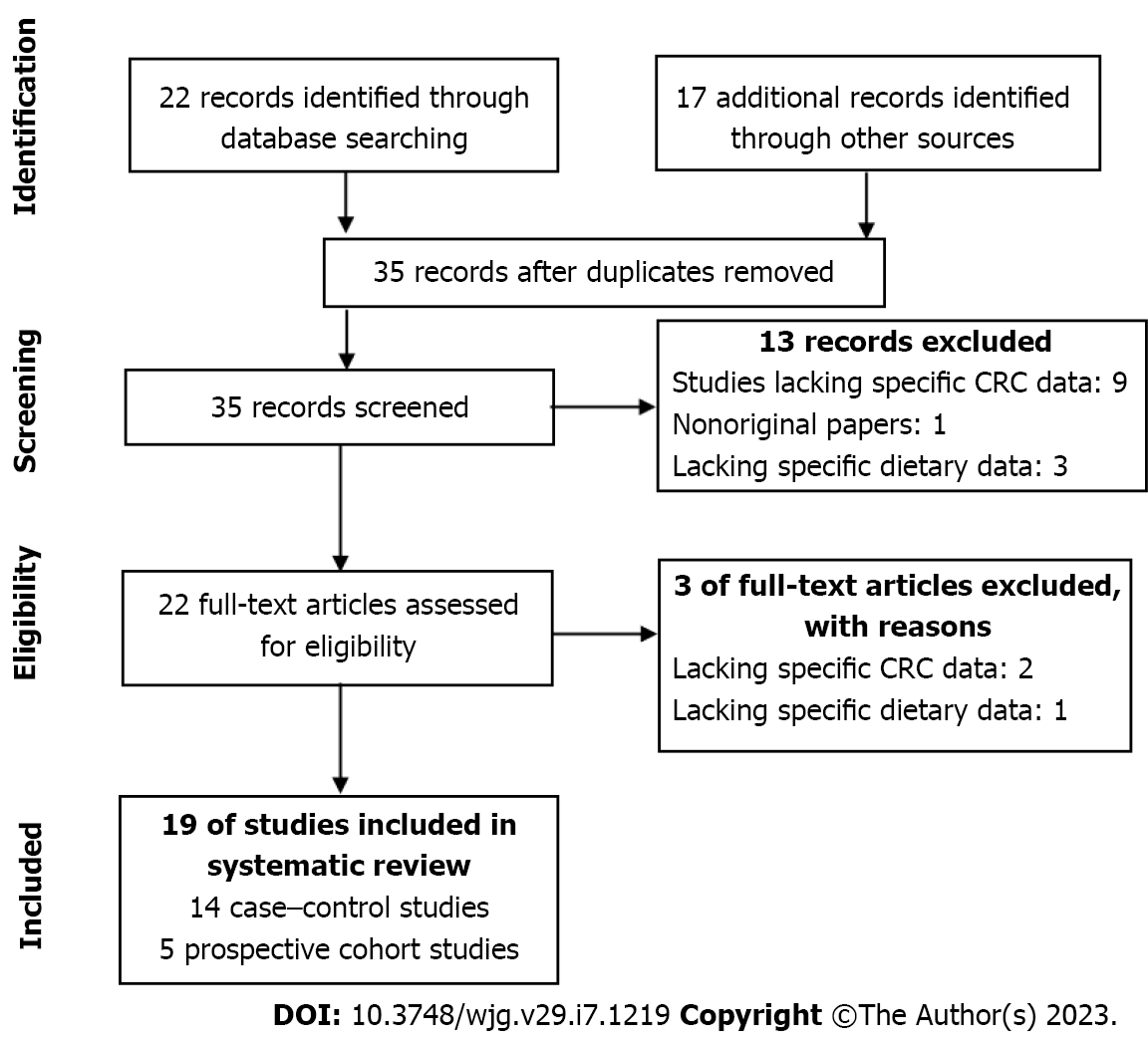

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram summarizing the identification and selection of the relevant publications. A total of nineteen studies were included in this systematic review: Fourteen case-control studies[23-36] and five cohort studies[9,37-40]. In total, the case-control studies included 7055 cases and 9032 controls. The cohort studies included 256914 participants, with 1109 cases recorded during follow-up periods that ranged from 7.3 to 22 years. Amongst the case-control studies, nine articles were conducted in the United States, two in the United Kingdom, two in Korea and one in Portugal. With regard to the cohort studies, three were conducted in the Netherlands and two in the United States.

Tables 1 and 2 summarize the main characteristics and findings of the case-control and cohort studies, respectively, on the interactive effect between single-nucleotide polymorphisms in genes encoding methyl-metabolizing enzymes, dietary methyl donors and dietary components that potentially modulate the bioavailability of methyl groups on CRC risk. Tables 3 and 4 show the effects of dietary methyl donors and dietary components that potentially modulate the bioavailability of methyl groups on CRC risk, according to SNPs in genes encoding methyl-metabolizing enzymes and/or mutations in oncogenes, CIMP and/or MSI, in the case-control studies and cohort studies, respectively. Table 5 provides a summary of the results of the studies included in the systematic review.

| Ref. | Country | Age (yr) | No. cases (M/W), endpoint | No. controls, type | Gene (SNP) | Nutrient/alcohol | Method for measuring nutrition intake | Outcome (OR, 95%CI) | Adjustments to OR | NOS | ||

| SNP | Nutrient/alcohol | Interaction | ||||||||||

| Chen et al[23] | United States | 40-75 | 144 M, CRC | 627 C | MTHFR (677C>T) | Dietary folate, Met, and alcohol | Validated FFQ (self-reported) | No assoc | Alcohol (≥ 5 vs ≤ 1 drinks/wk): 1.61 (1.01-2.58) | 677TT (vs CC/CT)-low alcohol consumption (≤ 1 drinks/wk): 0.11 (0.01-0.85) (P-interac = 0.02) | Age, CRC family history | 7 |

| Guerreiro et al[24] | Portugal | Cases (64.2 ± 11.3), controls (62.2 ± 12.1) | 104/92 CRC | 200 C | MTHFR (677C>T), MS (2756A>G), SHMT (1420C>T) | Dietary folate, vitamins B6 and B12, glycine, Met, serine, and alcohol | Validated FFQ (by interview) | 677TT (vs CC/CT): 3.01, (1.3-6.7); 1420TT (vs CC/CT): 2.6, (1.1-5.9) | Folate (> 406.7 mcg/d vs < 406.7 mcg/d): 0.67 (0.45-0.99) | 677TT (vs CC/CT)– folate (< 406.7 mcg/d): 14.0, 1.8-108.5 (P = 0.05) | Age, CRC history, and sex | 5 |

| Kim et al[25] | Korea | 30-79 | 465/322 CRC (363 CCa, 330 RCa) | 656 H | MTHFR(677C>T) | Dietary folate and alcohol | Validated FFQ | 677TT (vs CC/CT): 0.60 (0.46-0.78) | Folate (high vs low intake): 0.64 (0.49-0.84); alcohol (high vs low intake): 1.76 (1.26-2.46) | 677CC/CT–Low-methyl diet (folate < 209.69 mcg/d and alcohol ≥ 30 g/d): 2.32 (1.18-4.56) (P-interac = no assoc) | Age, BMI, CRC family history, energy intake, multivitamin use, sex, smoking status | 7 |

| Ma et al[26] | United States | 40-84 | 202 M, CRC | 326 C | MTHFR (677C>T) | Plasma folate, and alcohol consumption | FFQ (self-reported) | 677TT (vs CC): 0.45 (0.24-0.86) | Folate (plasma deficiency vs adequate levels): No assoc | 677TT (vs TC/CC)–folate (adequate levels): 0.32 (0.15-0.68) | Age, alcohol consumption, aspirin use, BMI, exercise, multivitamin use, and smoking status | 7 |

| Alcohol: Unk | 677TT (vs CC)–alcohol (0-0.14 drinks/d): 0.12 (0.03-0.57) | Age | ||||||||||

| Murtaugh et al[27] | United States | 30-79 | 446/305 RCa | 979 C | MTHFR (677C>T, 1298A>C) | Dietary folate, riboflavin, vitamins B6 and B12, Met, and alcohol | FFQ (by interview) | W, 677TT (vs CC): 0.54 (0.30-0.98). M&W, 1298CC (vs AA): 0.67 (0.46-0.98) | Dietary folate (> 475 mcg/d vs < = 322 mcg/d): 0.66 (0.48-0.92). High methyl donor status (vs low status): 0.79 (0.66-0.95) | No assoc | Age, BMI, ibuprofen use, intake of energy, fibre and calcium, PA, sex, and smoking status | 6 |

| Pufulete et al[28] | United Kingdom | 38-90 | 13/15 CRC | 76 C | MTHFR (677C>T, 1298A>C), MS (2756A>G), CBS (844ins68) | Plasma folate, vitamin B12, and homocysteine, alcohol and folate intake | Validated FFQ (by interview) | 677TT (vs CC): 5.98 (0.92-38.66), P = 0.06; 1298CC (vs AA): 12.6 (1.12-143.70), P = 0.04 | Folate status score (T3 vs T1): 0.09 (0.01-0.57), P-trend = 0.01 | Unk | Age, alcohol consumption, BMI, sex, and smoking status | 7 |

| Sharp et al[29] | United Kingdom | 150/114 (189 CCa, 75 RCa) | 408C | MTHFR (677C>T, 1298A>C) | Dietary folate, riboflavin, vitamins B6 and B12, and alcohol | Validated FFQ (self-reported) | No assoc | No assoc | 677CT/TT (vs CC)–folate (> mean): P-interac = 0.029. 677CT/TT (vs CC)–vitamin B6 (> mean): P-interac = 0.016 | Age, CRC family history, energy intake, NSAID use, PA, and sex | 6 | |

| Slattery et al[30] | United States | 30-79 | 824/849 CC (DCCa 405/303; PCCa 395/327) | 1816 C | MTHFR (677C>T) | Dietary folate, Met, vitamins B6 and B12, and alcohol | Validated CARDIA diet questionnaire | 677TT: No assoc | Unk | TT-low risk diet (high in folate and Met and without alcohol): 0.4 (0.1-0.9) | Age, BMI, intake of energy and fibre, PA, and smoking intensity | 7 |

| Ref. | Country | Study cohort (age, yr) | No. participants (M/W) | No. incident cases | Follow-up length, y | Gene (SNP) | Nutrient/alcohol | Method for measuring nutrition intake | Outcome (RR, 95%CI) | Adjustments to RR | NOS | ||

| SNP | Nutrient/alcohol | Interaction | |||||||||||

| de Vogel et al[9] | Netherlands | Netherlands Cohort Study on diet and cancer (55-69) | 58279/62573 | 734 CRC | 7.3 | MTHFR (rs1801133, rs1801131), MTR (rs1805087), MTRR (rs1801394), DNMT3B (rs2424913, rs406193), EHMT1 (rs4634736), EHMT2 (rs535586), PRDM2 (rs2235515) | Dietary folate, Met, vitamins B2 and B6, alcohol | Validated FFQ (self-reported) | Unk | Unk | ≤ 1 rare allele in folate metabolizing enzymes–vitamin B2 (T3 vs T1): 0.30, (0.11-0.81), P-trend = 0.005. Rare allele of DNMT3B C>T (rs406193)–vitamin B6 (T3 vs T1): 1.90 (1.00-3.60), P-trend = 0.04. Common allele of PRDM2 G>A (rs2235515)–vitamin B6 (T3 vs T1): 1.49 (1.00-2.22), P-trend = 0.03. No assoc | Age, alcohol consumption, BMI, CRC family history, intake of energy and alcohol, sex, and smoking status | 9 |

| Ref. | Country | Age (yr) | No. cases (M/W), endpoint | No. controls and type | Gene (SNP) | CIMP markers | MSI | Nutrient/alcohol | Method for measuring nutrition intake | Outcome (OR, 95%CI), interaction | NOS | ||

| CIMP markers/MSI–nutrient/alcohol | CIMP markers-/MSI–SNP–nutrient/alcohol | Adjustments to OR | |||||||||||

| Busch et al[31] | United States | 40-80 (AAs vs EAs) | 244/241 CRC | Analyses were only performed in tumour tissue | CACNA1G, hMLH1, NEUROG1, RUNX3, SOCS1 | Unk | Dietary folate and alcohol | Unk | EAs: High CACNA1G methylation tumour (cut point of 5%)–high folate intake: 0.3 (0.14-0.66); high SOCS1 methylation tumour (cut point of 3%)–high folate intake: 0.3 (0.11-0.80) | Unk | - | 4 | |

| Curtin et al[32] | United States | 30-79 | 518/398 CCa | 1972 C | MTHFR (677C>T, 1298A>C), TS variants (TSER, TTAAAG in 3´-UTRs 1494), MTR (919D>G), RFC (80G>A), MTHFD1 (R134K, R653Q), ADH3 (1045A>G) | MINT1, MINT2, MINT31, p16, hMLH1 | Unk | Dietary folate, Met, vitamin B12, and alcohol | Adaptation of the CARDIA diet history | Unk | MTHFR 1298AA–alcohol (high vs none): CIMP+, 0.5 (0.3-0.97), P < 0.01; ADH3 (1 or 2 variant, slow catabolizing*2 vs homozygous for the common allele)–folate (low): CIMP+, 1.6 (1.03-2.6), P = 0.02. MTHFR 1298AC or CC-high-risk dietary pattern (low in folate or Met intake, high in alcohol): CIMP+, 2.1 (1.3-3.4), P = 0.03 | Age, centre, other SNPs, sex, smoking intensity, and race | 9 |

| Curtin et al[33] | United States | 30-79 | 559/392 | 1205 C | MTHFR (1298A>C), TP53, KRAS2, | CDKN2A, hMLH1, MINT 1, 2 and 31 | Folate, riboflavin, vitamins B6, B12, and Met | Adaptation of the CARDIA diet history (by interview) | M: Folate (T3 vs T1)–CIMP+, 3.2 (1.5-6.7), P < 0.01 | 1298 AC/CC (vs AA)–folate (T3 vs T1): 0.4 (0.2-1.0), P = 0.04, for CIMP+ | Age, centre, intake of energy and fibre, NSAID use, oestrogen use (W), PA, race, referent year, sex, screening, and smoking | 8 | |

| Kim et al[34] | Korea | 30-79 | 465/322 CRC (363 CCa, 330 RCa) | 656 H | MTHFR (677C>T) | Unk | 2 mononucleotide markers (Bat25 and Bat26) and 3 dinucleotide markers (D2S123, D5S346, and D17S250) | Folate, vitamins B2, B6, B12, niacin, Met, and choline | Validated FFQ | Unk | DCCa: hMSH3 (rs41097) AG/GG (vs AA)–niacin (> 14.00 mg/d vs < 14.00 mg/d)–MSI–MMR status: 0.49 (0.28-0.84), P-interac = 0.008 | Age, intake of energy and alcohol, BMI, CRC family history, educational level, occupation, income, PA, sex, and smoking status | 7 |

| Slattery et al[35] | United States | 30-79 | 821/689 CRC | 2410 C | Unk | Unk | 10 tetranucleotide repeats, 3 Bat-26 and TGFbRII | Dietary folate, and alcohol | Validated CARDIA diet questionnaire | Alcohol–MSI+ (vs MSI-): 1.6 (1.0-2.5), P-trend = 0.03; liquor–MSI+ (vs MSI-): 1.6 (1.1-2.4), P-trend = 0.02 | Age, BMI, intake of energy, fibre and calcium, intake, PA, sex | 7 | |

| Slattery et al[36] | United States | 30-79 | 638/516 CRC | 2410 C | BRAF (V600E) | MINT1, MINT2, MINT31, p16 and hMLH1 | Unk | Folate, vitamins B6 and B12, Met, and alcohol | Diet history questionnaire | No assoc | MSI tumour–alcohol (high vs none): 1.6 (0.9-2.9), P-trend = 0.04, for p16 unmethylated; 1.7 (0.7-4.3), P-trend = 0.06, for CIMPlow (< 2 markers); 2.2 (1.2-3.7), P-trend = 0.01, for BRAF wildtype | Age, alcohol intake, BMI, intake of energy and folate, density of calcium and fibre, NSAIDs use, PA, sex, smoking intensity | 7 |

| Ref. | Country | Study cohort (age, yr) | No. participants (M/W) | No. incident cases | Follow-up length, yr | Gene (SNP) | CIMP markers | MSI | Nutrient/alcohol | Method for measuring nutrition intake | Outcome (RR, 95%CI) interaction | NOS | ||

| CIMP markers/MSI– | CIMP markers–/MSI–SNP– | Adjustments to RR | ||||||||||||

| de Vogel et al[9] | Netherlands | The Netherlands Cohort Study on diet and cancer (55-69) | 58279/62573 | 734 CRC | 7.3 | MTHFR (rs1801133, rs1801131), MTR (rs1805087), MTRR (rs1801394), DNMT3B (rs2424913, rs406193), EHMT1 (rs4634736), EHMT2 (rs535586), PRDM2 (rs2235515) | CACNA1G, IGF2, NEUROG1, RUNX3, SOCS1 | Bat-26, Bat-25, NR-21, NR-22, NR-24 | Dietary folate, Met, vitamins B2 and B6, alcohol | Validated FFQ (self-reported) | No assoc | Unk | BMI, CRC family history, intake of energy and alcohol, sex, and smoking status | 9 |

| de Vogel et al[37] | Netherlands | The Netherlands Cohort Study on diet and cancer (55-69) | 58279/62573 | 734 CRC | 7.3 | BRAF (V600E) | Dietary folate, Met, vitamins B2 and B6, alcohol | Validated FFQ (self-reported) | M: BRAF mut–folate (T3 vs T1): 3.04 (1.13-8.20), P-trend = 0.03; BRAF mut–Met (T3 vs T1): 0.28 (0.09-0.86), P-trend = 0.02); hMLH1 hypermethylation–vitamin B6 (T3 vs T1): 3.23 (1.15-9.06), P- trend = 0.03 | Unk | Age, BMI, CRC family history, intake of energy, meat, total fat, fibre, vitamin C, total iron and calcium, smoking status | 9 | ||

| Schernhammer et al[38] | United States | The Nurses' Health Study (W) (30-55) and the Health Professional Follow-up Study (M) (40–75) | 47371/88691 | 669 CCa | 22 | KRAS | Unk | D2S123, D5S346, D17S250, Bat25, Bat26 (14), Bat40, D18S55, D18S56, D18S67, D18S487 | Folate, vitamins B6 and B12, Met, and alcohol | Validated FFQ (self-reported) | Unk | MSI/KRAS–folate: No assoc for CCa. MSI/KRAS–vitamins B6 or B12: No assoc for CCa | Age, aspirin use, smoking, BMI, colon polyps, CRC family history, intake of alcohol, energy, beef, calcium, vitamins B6 and B12, and Met, multivitamin use, PA, sex, screening sigmoidoscopy | 9 |

| Schernhammer et al[39] | United States | The Nurses’ Health Study (30- 55) | 88691 W | 375 CCa | BRAF | CHFR, MGMT, p14, WRN, HTC1, MINT1, MINT31, IGFBP3 | Unk | Folate (Q4 vs Q1: No assoc with CIMP–high tumour risk; and no assoc with BRAF status | Unk | |||||

| van Engeland et al[40] | Netherlands | Netherlands Cohort Study on Diet and Cancer (55-69) | 58279/62573 | 122 CRC | 7.3 | Unk | APC-1A, p14ARF, p16INK4A, hMLH1, O6-MGMT, and RASSF1A | Unk | Dietary folate and alcohol | Validated FFQ (self-reported) | Low vs high-methyl donor intake–promoter methylation (> 1 gene methylated): No assoc | Unk | Age, CRC family history, intake of energy, fibre, vitamin C, and iron, sex | 9 |

| Gen, SNP/CIMP/MSI | Nutrients/alcohol | CRC risk/CIMP+ | Ref. |

| MTHFR 677 TT | Folate; Adequate folate | CRC risk; CRC risk | Guerreiro et al[24]; Sharp et al[29]; Ma et al[26] |

| Alcohol | CRC risk | Chen et al[23]; Ma et al[26] | |

| Folate/Met, and without alcohol | CRC risk | Slattery et al[30] | |

| Vitamin B6 | CRC risk | Sharp et al[29] | |

| BRAF mutation | Folate | CRC risk (M) | de Vogel et al[37] |

| Met | CRC risk (M) | ||

| hMLH1 hypermethylation | Vitamin B6 | CRC risk (M) | |

| MTHFR 1298 AC/CC | Folate/Met, and alcohol | CIMP+ | Curtin et al[32] |

| MTHFR 1298 AA | Alcohol | CIMP+ (CCa) | |

| p16 unmethylated, CIMPlow or BRAF mut | Alcohol | CRC risk | Slattery et al[36] |

| hMSH3, MSI or MMR status | Niacin | CRC risk (DCCa) | Kim et al[34] |

This review summarizes previous studies that have investigated the influence of methyl donor nutrients as epigenetic regulators in CRC. The dietary components that showed a higher association with CRC risk were folate and alcohol. Thus, high folate intake was considered a protective factor, while high alcohol consumption proved to be a risk factor. Several studies have investigated the association between methyl donor nutrients and/or methyl antagonists (e.g., alcohol) and MTHFR polymorphisms and have reported significant interactions[23,24,26,29,36]. In one of those case-control studies, those with the MTHFR 677 TT genotype, who consume low folate diets, had a greater chance of developing CRC than people with the CC or CT genotype[24]. Two other case-control studies reported that MTHFR 677 TT carriers with high (above mean) or adequate folate intake had a low risk of CRC[26,29].

Two case-control studies found that alcohol consumption increased CRC risk among MTHFR 677 TT carriers[23,26]. The decreased MTHFR enzyme activity among those who carried the T allele, and consumed low methyl donor nutrients and large amounts of alcohol can be utilised to explain the increased CRC risk[25,30]. These dietary habits may alter folate metabolism, especially in people with folate deficiencies[41]. In contrast, several studies have not found an association between MTHFR polymorphisms and either folate intake or alcohol intake and CRC risk[25,27]. It has been hypothesized that the differences in folate status among various populations may have influenced the contradictory results on the contribution of MTHFR genetic variants in CRC[25]. In addition to MTHFR poly

Regarding the methylation abnormalities of genes, de Vogel et al[37] found that high vitamin B6 intake was associated with an increased CRC risk caused by hypermethylation of the hMLH1 promoter among men. Therefore, these authors suggest that vitamin B6 may have had a tumour-promoting effect by increasing promoter methylation. However, the intake of folate, vitamin B2, Met and alcohol was not associated with the risk of tumours showing hMLH1 hypermethylation. In any case, other studies showed inverse associations between vitamin B6 intake and CRC risk, both when the intake level was higher6 and when it was similar[42] to that in the study of de Vogel et al[37]. Therefore, further attention should be given to this association in future studies.

Another interesting finding in this review is the inverse association between dietary folate and Met and B-Raf proto-oncogene mutations among men[37]. A previous study showed that folate may increase the risk of tumours harbouring truncating adenomatous polyposis coli mutations in men[43]. Apparently, relatively high folate intake may confer a growth advantage to mutated tumours independent of the type of mutation. Nevertheless, the occurrence of MSI does not seem to be sensitive to methyl donor intake or to that of alcohol[36-37,44].

In one of the case-control studies that we analysed, an interaction was observed between a high- or low-risk diet and MTHFR 1298A>C (but not 677C>T) with regard to CIMP status[32]. This result suggests that a genetic polymorphism at MTHFR 1298A>C interacts with the diet (with a low folate and Met intake and a high alcohol consumption) increasing the risk of highly CpG-methylated colon tumours. S-adenosylmethionine binds as an allosteric inhibitor in the MTHFR regulatory region, which is where the 1298A>C variant is found. This gives some justification for the stronger associations between MTHFR 1298A>C and CIMP rather than the 677C>T SNP, which has an opposite effect on the stability of the enzyme. Due to their high linkage disequilibrium, the MTHFR 677C>T and 1298A>C polymorphisms should not be viewed separately. van Engeland et al[40] also discovered that people diagnosed with CRC, with low intake of folate and high consumption of alcohol, had a greater prevalence of promoter hypermethylation; however, the difference was not statistically significant due to limited power. Therefore, it was proposed that stratification for functionally significant SNPs in the genes encoding folate metabolism enzymes could strengthen the observed effect of folate deficiency on promoter methylation[40].

Additionally, Curtin et al´s study[32] found an interaction between alcohol consumption and MTHFR 1298A>C in association with CIMP status. Relative to the AA genotype in non-drinkers, the MTHFR 1298 AA genotype was linked to a higher risk of CIMP+ in drinkers. In a previous study by Slattery et al[35], in which associations between CIMP status and alcohol use were assessed without taking into regard to genotype, no association was observed. These results imply that the activity of the 1C-metabolism enzyme may alter the risk associated with alcohol in determining the CIMP status of colon cancer. In any case, to date, few published studies have evaluated, CIMP in CRC for possible relationships with 1C-metabolism SNPs[32,45,46]. Moreover, these data raise the possibility that more investigation is required to clarify the function of genetic SNPs in relation to CIMP status and the promoter hypermethylation of particular genes.

In one case-control study[36], an association between long-term alcohol consumption and increased likelihood of having a CIMP-low or B-Raf proto-oncogene-mutated tumour was observed. Among those with unstable tumours, they observed that alcohol was more likely to be associated with CIMP-low rather than CIMP-high tumours. A previous study of these same authors showed that alcohol increased the risk for MSI+ tumours in general[35]. Therefore, these findings suggest that the increased risk of MSI associated with alcohol is limited to those tumours that are unmethylated rather than methylated.

Finally, regarding the interaction between MMR SNPs and methyl donor nutrient intake on CRC based on MSI status, in a case-control study[34], a strong inverse association was observed for hMSH3 AG or GG carriers with a high intake of niacin, particularly among patients with CC and microsatellite stability or proficient MMR status. However, to ascertain the processes behind this association with CRC risk, the precise roles of this SNP must be identified.

The importance of interactions between modifiable factors, such as methyl donor nutrients and CRC, is suggested by evidence that colorectal carcinogenesis is generated by numerous molecular pathways in parallel with MSI status, which is caused by a defect in the MMR machinery. In this sense, it is worth remembering the article mentioned by de Vogel et al[37], in which it was reported that high consumption of vitamin B6 was linked to an increased risk of sporadic CRC with hMLH1 hypermethylation, indicating that vitamin B6 affects CRC risk through both genetic and epigenetic mechanisms. Based on the findings of Kim et al[34], it may be possible to explain the interactions between dietary methyl donor nutrients, such as niacin, and hMSH3 genetic variants as predictors of CRC risk.

DNA methylation and microRNA expression levels may be regulated by the MMR machinery’s epigenetic relationships with methyl groups[47]. Through the methylation of CpG islands in the promoter region, 1C metabolism mediated by methyl donor nutrients can change how the DNA MMR system is activated. A adequate DNA MMR system with methyl groups may control the equilibrium between the repair and accumulation of short repeat sequences, preventing extensive DNA damage that supports colorectal carcinogenesis.

This systematic review has several strengths: (1) Cohort and case-control studies were identified through a systematic search; (2) a quantitative NOS scale was used to assess the quality of the studies; and (3) most studies (twelve of nineteen) used a validated questionnaire to assess dietary intake. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review regarding the influence of methyl donor nutrients as epigenetic regulators in CRC.

The limitations of this review include the following: (1) Case-control studies, which are susceptible to recall and selection bias, made up the bulk of the research. However, most studies were based on community controls; thus, they might be a good representation of the frequency of genetic variants or of dietary habits of the overall population; (2) the heterogeneous nature of studies, including the study population characteristics, sample size, study design, and follow-up periods; (3) potential residual confounding because of the observational nature of the studies included or the possibility that not all the studies were adjusted for important nutrient variables; (4) some of the dietary assessments were self-reported, which may affect the reliability of the reported intakes, although the use of validated questionnaires in most studies could reduce this bias; (5) some studies had a relatively limited sample size or effect size, which made it difficult for them to detect the interactions between genetic and nutritional information, which could explain, in part, the lack of results with a statistically significant level; and (6) despite the fact that some research have found differential interactions based on the CRC subtype[34], the majority of studies lacked stratified analysis. Considering these limitations, the conclusions from these researchers should be taken carefully. Consequently, it is difficult for this review to explain the gene-diet interactions and their effects on the development of CRC.

In this systematic review of observational studies, some interactions between MTHFR polymorphisms, methyl donor nutrients (such as folate) and alcohol on CRC risk are suggested. Moreover, some studies show that vitamin B6, niacin and alcohol may affect CRC risk through not only genetic but also epigenetic regulation. In any case, this review was not able to clarify which mechanisms underlie the influence of methyl donor nutrients on DNA methylation, as well as the efficacy of methyl uptake, transportation, and the final involvement in methyl-related gene expression. Further prospective studies with large samples and long follow-up periods, as well as clinical trials that take into account the long latency period of CRC, are needed to clarify the influence of methyl group donors as epigenetic regulators, with particular emphasis on differences in CRC subsite-specific risk. Such studies may provide valuable insight into the biological mechanisms with the goal of identifying at-risk subpopulations and promoting primary prevention of CRC.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most frequent cancer and is responsible for the second-highest mortality rate in cancer patients worldwide. The main factors which may help prevent CRC are those associated with diet, lifestyle, and prevention of metabolic diseases. With regards to the dietary component, one-carbon metabolism-related nutrients have been considered anticarcinogenic and chemotherapeutic agents in the one-carbon metabolic network. However, it is still unclear whether the influence of methyl donor intake is modified by polymorphisms in these epigenetic regulators.

Although screening for early detection of CRC is effective to help decrease the trends in mortality rates, understanding daily life factors is also important to prevent this type of cancer. A better understanding of the molecular basis of CRC could contribute to a better design of future research and better preventive nutritional management in this type of cancer.

In the present work, we reviewed previous studies that have investigated this matter to improve the current understanding of the molecular basis of CRC.

A literature search in the Medline database, Reference Citation Analysis (https://www.referencecitationanalysis.com/, an artificial intelligence technology-based open multidisciplinary citation analysis database), and manual reference screening were performed to identify observational studies published from inception to May 2022. A search for relevant keywords and medical subject heading terms related to dietary methyl donors, dietary components that potentially modulate the bioavailability of methyl groups, genetic variants of methyl-metabolizing enzymes, markers of CpG island methylator phenotype and/or microsatellite instability, in combination with keywords related to CRC events was conducted. The present search was developed according to the “PRISMA Statement” guidelines. To evaluate the validity of the individual studies, two reviewers worked independently to determine the quality of the included studies based on the use of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for case-control or cohort studies.

A total of fourteen case-control studies and five cohort studies were identified. In total, the case-control studies included 7055 cases and 9032 controls. The cohort studies included 256914 participants, with 1109 cases recorded during follow-up periods that ranged from 7.3 to 22 years. The dietary components that showed a higher association with CRC risk were folate and alcohol. Thus, high folate intake was considered a protective factor, while high alcohol consumption proved to be a risk factor. Several studies have investigated the association between methyl donor nutrients and/or methyl antagonists (e.g., alcohol) and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) polymorphisms and have reported significant interactions. In one of those case-control studies, those with the MTHFR 677 TT genotype, who consume low folate diets, had a greater chance of developing CRC than people with the CC or CT genotype. Two other case-control studies reported that MTHFR 677 TT carriers with high (above mean) or adequate folate intake had a low risk of CRC.

In this systematic review of observational studies, some interactions between MTHFR polymorphisms, methyl donor nutrients (such as folate), and alcohol on CRC risk are suggested. Moreover, some studies show that vitamin B6, niacin, and alcohol may affect CRC risk through not only genetic but also epigenetic regulation.

This review was not able to clarify which mechanisms underlie the influence of methyl donor nutrients on DNA methylation, as well as the efficacy of methyl uptake, transportation, and the final involvement in methyl-related gene expression. Further prospective studies with large samples and long follow-up periods, as well as clinical trials that consider the long latency period of CRC, are needed to clarify the influence of methyl group donors as epigenetic regulators, with particular emphasis on differences in CRC subsite-specific risk.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Spain

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Liu Z, China; Yang JS, China S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 64539] [Article Influence: 16134.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (176)] |

| 2. | Keum N, Giovannucci E. Global burden of colorectal cancer: emerging trends, risk factors and prevention strategies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:713-732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 777] [Cited by in RCA: 1578] [Article Influence: 263.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Puzzono M, Mannucci A, Grannò S, Zuppardo RA, Galli A, Danese S, Cavestro GM. The Role of Diet and Lifestyle in Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hanley MP, Rosenberg DW. One-Carbon Metabolism and Colorectal Cancer: Potential Mechanisms of Chemoprevention. Curr Pharmacol Rep. 2015;1:197-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Choi SW, Mason JB. Folate status: effects on pathways of colorectal carcinogenesis. J Nutr. 2002;132:2413S-2418S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kune G, Watson L. Colorectal cancer protective effects and the dietary micronutrients folate, methionine, vitamins B6, B12, C, E, selenium, and lycopene. Nutr Cancer. 2006;56:11-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Crott JW, Mason JB. MTHFR polymorphisms and colorectal neoplasia. In: Ueland PM, Rozen R, editors. MTHFR polymorphisms and Disease. Georgetown, Texas, USA: Eurekah.com/Landes Bioscience; 2005: 178–196. |

| 8. | Ma J, Stampfer MJ, Christensen B, Giovannucci E, Hunter DJ, Chen J, Willett WC, Selhub J, Hennekens CH, Gravel R, Rozen R. A polymorphism of the methionine synthase gene: association with plasma folate, vitamin B12, homocyst(e)ine, and colorectal cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8:825-829. [PubMed] |

| 9. | de Vogel S, Wouters KA, Gottschalk RW, van Schooten FJ, de Goeij AF, de Bruïne AP, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA, van Engeland M, Weijenberg MP. Dietary methyl donors, methyl metabolizing enzymes, and epigenetic regulators: diet-gene interactions and promoter CpG island hypermethylation in colorectal cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chen J, Kyte C, Valcin M, Chan W, Wetmur JG, Selhub J, Hunter DJ, Ma J. Polymorphisms in the one-carbon metabolic pathway, plasma folate levels and colorectal cancer in a prospective study. Int J Cancer. 2004;110:617-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kim YI. Folate and DNA methylation: a mechanistic link between folate deficiency and colorectal cancer? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:511-519. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Schernhammer ES, Giovannucci E, Kawasaki T, Rosner B, Fuchs CS, Ogino S. Dietary folate, alcohol and B vitamins in relation to LINE-1 hypomethylation in colon cancer. Gut. 2010;59:794-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pufulete M, Al-Ghnaniem R, Khushal A, Appleby P, Harris N, Gout S, Emery PW, Sanders TA. Effect of folic acid supplementation on genomic DNA methylation in patients with colorectal adenoma. Gut. 2005;54:648-653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Weisenberger DJ, Siegmund KD, Campan M, Young J, Long TI, Faasse MA, Kang GH, Widschwendter M, Weener D, Buchanan D, Koh H, Simms L, Barker M, Leggett B, Levine J, Kim M, French AJ, Thibodeau SN, Jass J, Haile R, Laird PW. CpG island methylator phenotype underlies sporadic microsatellite instability and is tightly associated with BRAF mutation in colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2006;38:787-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1423] [Cited by in RCA: 1498] [Article Influence: 78.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | de Vogel S, Wouters KA, Gottschalk RW, van Schooten FJ, de Goeij AF, de Bruïne AP, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA, Weijenberg MP, van Engeland M. Genetic variants of methyl metabolizing enzymes and epigenetic regulators: associations with promoter CpG island hypermethylation in colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:3086-3096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Inamura K. Colorectal Cancers: An Update on Their Molecular Pathology. Cancers (Basel). 2018;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | De' Angelis GL, Bottarelli L, Azzoni C, De' Angelis N, Leandro G, Di Mario F, Gaiani F, Negri F. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Acta Biomed. 2018;89:97-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hou JT, Zhao LN, Zhang DJ, Lv DY, He WL, Chen B, Li HB, Li PR, Chen LZ, Chen XL. Prognostic Value of Mismatch Repair Genes for Patients With Colorectal Cancer: Meta-Analysis. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2018;17:1533033818808507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wheeler JM, Bodmer WF, Mortensen NJ. DNA mismatch repair genes and colorectal cancer. Gut. 2000;47:148-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research Internet. Continuous Update Project Expert Report; 2018. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and colorectal cancer. [cited 10 August 2023]. Available from: https://www.wcrf.org/diet-activity-and-cancer/. |

| 21. | Anderson OS, Sant KE, Dolinoy DC. Nutrition and epigenetics: an interplay of dietary methyl donors, one-carbon metabolism and DNA methylation. J Nutr Biochem. 2012;23:853-859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 466] [Cited by in RCA: 506] [Article Influence: 38.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa: Ottawa Hosp Res Institute; 2011. |

| 23. | Chen J, Giovannucci E, Kelsey K, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Spiegelman D, Willett WC, Hunter DJ. A methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphism and the risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4862-4864. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Guerreiro CS, Carmona B, Gonçalves S, Carolino E, Fidalgo P, Brito M, Leitão CN, Cravo M. Risk of colorectal cancer associated with the C677T polymorphism in 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase in Portuguese patients depends on the intake of methyl-donor nutrients. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1413-1418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kim J, Cho YA, Kim DH, Lee BH, Hwang DY, Jeong J, Lee HJ, Matsuo K, Tajima K, Ahn YO. Dietary intake of folate and alcohol, MTHFR C677T polymorphism, and colorectal cancer risk in Korea. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:405-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ma J, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci E, Artigas C, Hunter DJ, Fuchs C, Willett WC, Selhub J, Hennekens CH, Rozen R. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphism, dietary interactions, and risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1098-1102. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Murtaugh MA, Curtin K, Sweeney C, Wolff RK, Holubkov R, Caan BJ, Slattery ML. Dietary intake of folate and co-factors in folate metabolism, MTHFR polymorphisms, and reduced rectal cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18:153-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Pufulete M, Al-Ghnaniem R, Leather AJ, Appleby P, Gout S, Terry C, Emery PW, Sanders TA. Folate status, genomic DNA hypomethylation, and risk of colorectal adenoma and cancer: a case control study. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1240-1248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sharp L, Little J, Brockton NT, Cotton SC, Masson LF, Haites NE, Cassidy J. Polymorphisms in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene, intakes of folate and related B vitamins and colorectal cancer: a case-control study in a population with relatively low folate intake. Br J Nutr. 2008;99:379-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Slattery ML, Potter JD, Samowitz W, Schaffer D, Leppert M. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, diet, and risk of colon cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8:513-518. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Busch EL, Galanko JA, Sandler RS, Goel A, Keku TO. Lifestyle Factors, Colorectal Tumor Methylation, and Survival Among African Americans and European Americans. Sci Rep. 2018;8:9470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Curtin K, Slattery ML, Ulrich CM, Bigler J, Levin TR, Wolff RK, Albertsen H, Potter JD, Samowitz WS. Genetic polymorphisms in one-carbon metabolism: associations with CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) in colon cancer and the modifying effects of diet. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1672-1679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Curtin K, Samowitz WS, Ulrich CM, Wolff RK, Herrick JS, Caan BJ, Slattery ML. Nutrients in folate-mediated, one-carbon metabolism and the risk of rectal tumors in men and women. Nutr Cancer. 2011;63:357-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kim J, Lee J, Oh JH, Sohn DK, Shin A, Kim J, Chang HJ. Dietary methyl donor nutrients, DNA mismatch repair polymorphisms, and risk of colorectal cancer based on microsatellite instability status. Eur J Nutr. 2022;61:3051-3066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Slattery ML, Anderson K, Curtin K, Ma KN, Schaffer D, Samowitz W. Dietary intake and microsatellite instability in colon tumors. Int J Cancer. 2001;93:601-607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Slattery ML, Curtin K, Sweeney C, Levin TR, Potter J, Wolff RK, Albertsen H, Samowitz WS. Diet and lifestyle factor associations with CpG island methylator phenotype and BRAF mutations in colon cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:656-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | de Vogel S, Bongaerts BW, Wouters KA, Kester AD, Schouten LJ, de Goeij AF, de Bruïne AP, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA, van Engeland M, Weijenberg MP. Associations of dietary methyl donor intake with MLH1 promoter hypermethylation and related molecular phenotypes in sporadic colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1765-1773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Schernhammer ES, Giovannuccci E, Fuchs CS, Ogino S. A prospective study of dietary folate and vitamin B and colon cancer according to microsatellite instability and KRAS mutational status. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2895-2898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Schernhammer ES, Giovannucci E, Baba Y, Fuchs CS, Ogino S. B vitamins, methionine and alcohol intake and risk of colon cancer in relation to BRAF mutation and CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP). PLoS One. 2011;6:e21102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | van Engeland M, Weijenberg MP, Roemen GM, Brink M, de Bruïne AP, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA, Baylin SB, de Goeij AF, Herman JG. Effects of dietary folate and alcohol intake on promoter methylation in sporadic colorectal cancer: the Netherlands cohort study on diet and cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3133-3137. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Giovannucci E. Alcohol, one-carbon metabolism, and colorectal cancer: recent insights from molecular studies. J Nutr. 2004;134:2475S-2481S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Ishihara J, Otani T, Inoue M, Iwasaki M, Sasazuki S, Tsugane S; Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study Group. Low intake of vitamin B-6 is associated with increased risk of colorectal cancer in Japanese men. J Nutr. 2007;137:1808-1814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | de Vogel S, van Engeland M, Lüchtenborg M, de Bruïne AP, Roemen GM, Lentjes MH, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA, de Goeij AF, Weijenberg MP. Dietary folate and APC mutations in sporadic colorectal cancer. J Nutr. 2006;136:3015-3021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Campbell PT, Curtin K, Ulrich CM, Samowitz WS, Bigler J, Velicer CM, Caan B, Potter JD, Slattery ML. Mismatch repair polymorphisms and risk of colon cancer, tumour microsatellite instability and interactions with lifestyle factors. Gut. 2009;58:661-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Oyama K, Kawakami K, Maeda K, Ishiguro K, Watanabe G. The association between methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphism and promoter methylation in proximal colon cancer. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:649-654. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Paz MF, Avila S, Fraga MF, Pollan M, Capella G, Peinado MA, Sanchez-Cespedes M, Herman JG, Esteller M. Germ-line variants in methyl-group metabolism genes and susceptibility to DNA methylation in normal tissues and human primary tumors. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4519-4524. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Yamamoto H, Imai K. Microsatellite instability: an update. Arch Toxicol. 2015;89:899-921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |