Published online Feb 14, 2023. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v29.i6.1109

Peer-review started: September 13, 2022

First decision: November 5, 2022

Revised: November 18, 2022

Accepted: December 30, 2022

Article in press: December 30, 2022

Published online: February 14, 2023

Processing time: 149 Days and 12.6 Hours

The impact caused by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on the Portuguese population has been addressed in areas such as clinical manifestations, frequent comorbidities, and alterations in consumption habits. However, comorbidities like liver conditions and changes concerning the Portuguese population's access to healthcare-related services have received less attention.

To (1) Review the impact of COVID-19 on the healthcare system; (2) examine the relationship between liver diseases and COVID-19 in infected individuals; and (3) investigate the situation in the Portuguese population concerning these topics.

For our purposes, we conducted a literature review using specific keywords.

COVID-19 is frequently associated with liver damage. However, liver injury in COVID-19 individuals is a multifactor-mediated effect. Therefore, it remains unclear whether changes in liver laboratory tests are associated with a worse prognosis in Portuguese individuals with COVID-19.

COVID-19 has impacted healthcare systems in Portugal and other countries; the combination of COVID-19 with liver injury is common. Previous liver damage may represent a risk factor that worsens the prognosis in individuals with COVID-19.

Core Tip: This review analyzes how the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) affects health care and clinical practice in Portugal and the possible causes of liver injury in COVID-19 individuals, including the direct effect of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 on the liver and drug-induced liver injury, and how preexisting liver diseases affect the treatment of COVID-19.

- Citation: Fernandes S, Sosa-Napolskij M, Lobo G, Silva I. Relation of COVID-19 with liver diseases and their impact on healthcare systems: The Portuguese case. World J Gastroenterol 2023; 29(6): 1109-1122

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v29/i6/1109.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v29.i6.1109

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is usually characterized by cough, headache, fever, muscle pain, general weakness, difficulty breathing, fatigue, and loss of taste and smell[1,2]. More severe cases may present pneumonia with fever, cough, dyspnea, and respiratory failure[1,2].

These symptoms may be aggravated by preexisting health conditions or comorbidities, which have been addressed in studies on the clinical characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19 individuals[2-4] published since the official declaration of the pandemic outbreak of COVID-19 on March 11, 2020[5].

Some of the most frequent comorbidities described in these studies are hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, and cancer[2-4]. In addition, despite not being among the most frequent comorbidities, the pathologies associated with the liver are hardly ever missing from the list of preexisting health conditions in COVID-19 individuals[6]. For example, a study that associated comorbidities with COVID-19 severity and hospitalization found that, concerning liver diseases, similarly to other studies[7,8], individuals with previous hepatic disorders (HD) were at a higher risk of developing symptoms when infected with SARS-CoV-2[9].

In Portugal, several studies have also focused on characterizing the clinical manifestations and outcomes of COVID-19[10-13], and some others have synthesized the clinical manifestations of COVID-19, for example, in the gastrointestinal system[14], in organs like the lungs, heart, kidney, and brain[15], or target specific population like children[16].

However, to date and the best of our knowledge, only one study has been published with a review of the impact of COVID-19 on the liver in the Portuguese population since 2020[17]. Data on individuals with COVID-19 who were also living with liver diseases and the implications and outcomes of this co-occurrence of health problems in the Portuguese population is ostensibly scarce. Likewise, the alterations in the healthcare system due to the pandemic and their association with COVID-19 and liver diseases have received little attention. Therefore, in this study, by reviewing the available research, we aimed to study the incidence of preexisting liver-associated diseases and liver injuries induced by COVID-19 in adults in Portugal and investigate the relationship of COVID-19 with liver diseases. On the other hand, we also seek to analyze how the COVID-19 pandemic affected access to healthcare systems and reflect on how societies should prepare for other pandemic crises in the future, thus contributing to the general and clinical body of knowledge on this topic.

The protocol used in this review included the following elements: (1) Research objective as specified in the introduction; (2) Eligibility criteria; (3) Search strategy and selection of studies; (4) Ethical considerations; (5) Quality assessment; and (6) Data extraction and analysis.

All the studies assessed in this review comply with the following inclusion criteria established beforehand by the authors: (1) Studies reporting original research published in Portuguese or English; (2) Targeting the Portuguese adult population, i.e., 18 years old or older; (3) From any period since the official diagnosis of the first case of COVID-19 in Portugal on March 2, 2020[18]; and (4) Reporting any liver-associated clinical manifestation or outcome.

Any study that: (1) Was duplicated; (2) Was not an original research article, i.e., was a case report, a conference article or an abstract-only article, a comment, a letter or editorial, an expert opinion, etc.; (3) Was not the final, and definite publication of the article (pre-print or accepted stage of the editorial process); or (4) Did not have data or did not refer to liver-associated diseases, was excluded.

First, the authors discussed the keywords to be used in the search, agreeing upon the following string and operators: ["Portugal" or "Portuguese patients" AND "COVID" OR "SARS-CoV-2" OR "coronavirus" AND "liver" or "hepatic condition" OR "chronic hepatitis" AND "clinical manifestations" OR "outcomes" AND "COVID-19 treatment"] to be found either in the titles, abstracts, or keywords of the articles.

The analysis began with a search of the literature available using the software Publish or Perish[19] to survey the databases PubMed, Scopus, CrossRef, Google Scholar, and Web of Science. Any study containing the string and operators mentioned before, either in the title or the abstract, was to be examined. The search was carried out on June 17, 2022, and the results of the search were exported to an Excel table.

A two-stage approach was used to assess the retrieved studies. First, only the titles and abstracts were scanned to determine eligibility according to the research objective and criteria. Second, the full texts of the selected papers were read and thoroughly analyzed. All the authors participated in these analyses.

Additionally, several other sources were examined to develop and elaborate on the results obtained. Some of these sources are other papers on the main topics of this review and the Portuguese National Health System (NHS), which was consulted for official information on COVID-19 and the health services at the time of the pandemic.

This study reports the review of published original research articles. Each assessed study addressed ethical specifications and approvals required by deontological practices and the law to be carried out and published. We did not recruit participants or request any information on any individual. Therefore, no formal consent or approval from any ethics committee was required.

The design of the protocol included meetings to discuss procedures and results. Cases of disagreement between the reviewers would have been resolved by resorting to two other independent researchers in the field. However, a consensus was reached about the studies to be included and excluded and the results of the analyses.

Likewise, all studies considered in this review were assessed methodologically to determine if biases were minimized or excluded. Finally, all the results are reported narratively and using tables.

We retrieved 804 articles from the database search. Of those, eight articles were duplicated and, therefore, eliminated. Then, the title and abstract of the 796 studies selected were screened, and 748 articles were excluded for: (1) Not referring to Portugal (n = 747); and (2) Not having the full text of the article available (n = 1) (Figure 1).

The remaining articles (n = 48) were equally distributed among the authors to assess based on the inclusion criteria. Of those, 42 articles were excluded for: (1) Not referring to the liver but instead covering comorbidities in the Portuguese population related to areas such as the cardiovascular system[20], kidney pathologies[13], respiratory system[10,21], mental health in the elderly[22], and a survey to parents on the use of healthcare services during the COVID-19 pandemic[23] (n = 27); (2) Due to lack of information to verify if the inclusion criteria were met (n = 11); (3) Not referring to data related to the liver or COVID-19 (n = 3); and (4) Referring to data on the liver but not under COVID-19 conditions (n = 1).

Finally, six studies complied with the inclusion criteria. Figure 1 shows the selection process flowchart, and the reviewed articles' characteristics are described in Table 1 of the section: Liver diseases and COVID-19 in Portuguese individuals.

| Ref. | Breadth and type of study | Analyzed individuals | Data source | Period of data collection | Age range (yr) | Preexisting liver disease (%) | Study findings |

| [63] | National Retrospective (observational) study | 20.293 | SINAVE (DGS) | January 1-April 21, 2020 | [0 to > 86] | 0.53% | Risk of mortality: (1) Higher in the male gender; (2) Higher in older age groups; and (3) Increases with the presence of comorbidities |

| [61] | National Retrospective observational study | 36.244 | DGS | March 2–June 30, 2020 | [18 to > 80] | 0.57% | The presence of simultaneous diseases is significantly associated with negative outcomes in individuals with COVID-19 |

| [60] | National Retrospective cohort study | 38.545 | DGS | March 2–June 30, 2020 | [0 to > 70] | 0.60% | Risk of hospitalization: (1) Lower in females; (2) Increases with age; and (3) Increases with the presence of comorbidities |

| [62] | National Retrospective cohort study | 20.293 | DGS | March 1-April 28, 2020 | [0 to > 90] | 0.50% | Risk of hospitalization, ICU admission, and death: (1) Higher in males; (2) Increases with age; and (3) Increases with the presence of comorbidities |

| [64] | National Retrospective (observational) study | 6.701 | SICO DGS) | The year 2020 | [0 to > 0] | No information available | The risk of hospitalization and lethality is higher in males and increases with age |

| [59] | A retrospective cohort study in a university hospital center | 317 | University Hospital Center of Porto (CHUP) | March 2-May 4, 020 | [18 to 5] | 4.42% | Hepatic enzyme changes in COVID-19 individuals were frequent but mostly mild; AST, unlike ALT, was associated with worse clinical outcomes, such as the severity of COVID-19 and mortality |

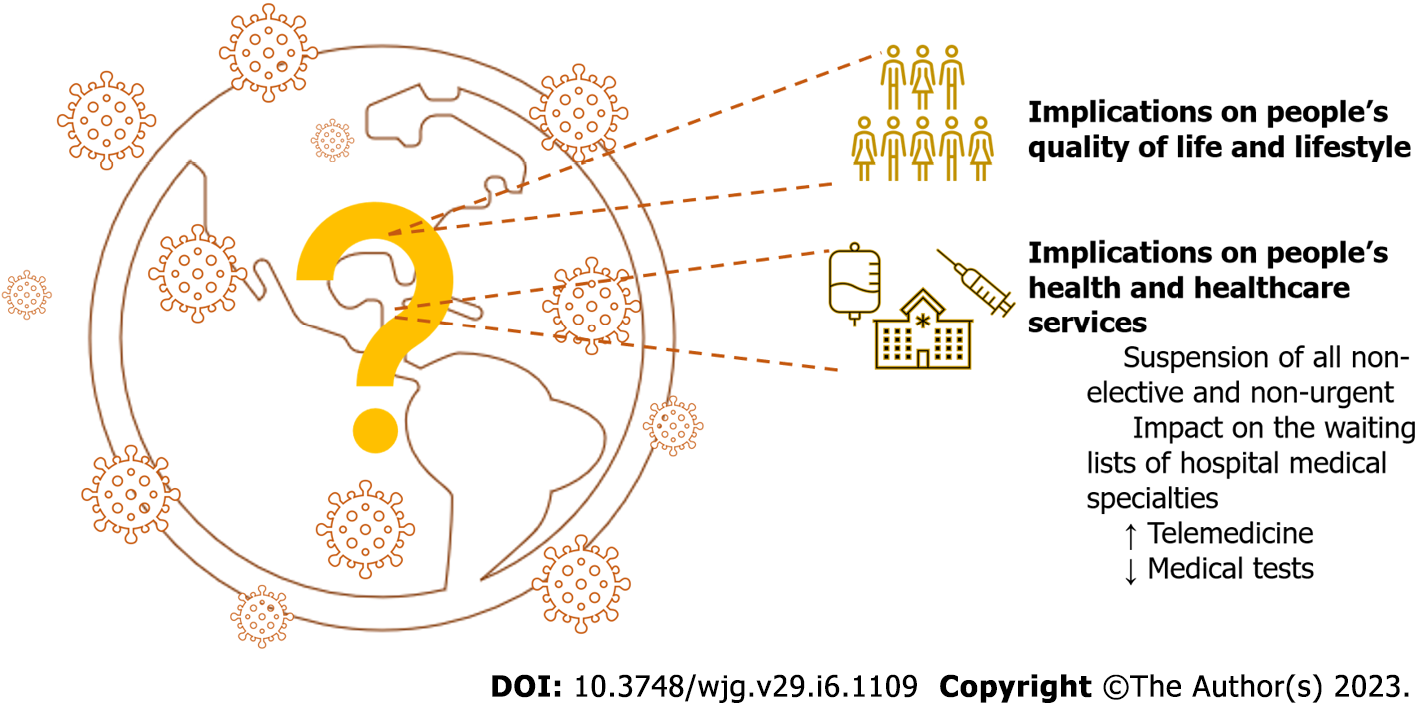

COVID-19 has greatly affected the Portuguese population's life, modifying their lifestyle, especially consumption habits[24]. Socialization with friends and family was reduced due to measures such as social distancing and restriction of access to many public services adopted to break the COVID-19 transmission chains. In Portugal, the National Health Service also enforced the suspension of all elective and non-urgent health care[25]. This measure had long-term consequences, such as an impact on the waiting lists for hospital medical specialties for first evaluation or other complex procedures/treatments (for example, surgeries and physiotherapy). During that period, all laboratories were exclusively dedicated to testing for COVID-19, reducing non-urgent activities and re-organizing their tasks.

Primary health services were also impacted, and many appointments were canceled or modified. A Portuguese study by Vieira et al[26] investigated all medical appointments in a primary care unit in the central region of Portugal from March 1 to July 31, 2020, and in the same period of 2019 and 2018. The authors observed that, contrary to what was expected, there was an increase (about 14% when compared with 2018 and 4% when compared with 2019) in the number of medical appointments in 2020 compared with the same period of 2018 and 2019. However, most of these appointments were teleconsultations performed by e-mail or phone compared with previous years (71.6% in 2020, 42.6% in 2019, and 35.2% in 2018). On the other hand, there was also a decrease in most follow-up and routine appointments and an increment in psychiatric diagnoses, mainly anxiety-related disorders[26]. Although this study demonstrated that the total number of medical appointments increased in 2020, mostly due to teleconsultations, this increase may not have reflected the general situation in other primary health units across the country. One reason for this hypothesis is that the central region in Portugal was less affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in the period when the study was performed. If the same study had been replicated in the northern region, the results would have been different. Data from the NHS revealed that in March 2020, a reduction of 16% in speciality medical appointments in public hospitals was observed compared with the same period of 2019. This negative variation was even greater in the following months, April and May, when it increased to 25% and 31%, respectively[27]. The first specialty medical appointment in the hospital was also reduced in these months in 2020 when compared with 2019. However, telemedicine appointments (not face-to-face appointments) increased[27]. The number of scheduled and urgent surgeries also decreased in these months by 15%, 38%, and 32% compared with March, April, and May of 2019, respectively. The emergency cases arriving at the hospital also decreased during this period[28].

When the data from January to July 2019 and 2020 were compared, a reduction in face-to-face appointments, an increase in telemedicine, and a reduction in medical tests were observed. Regarding the latter, pathological anatomy tests decreased by 36%, and tests concerning surgery medical specialties, which may study the liver, decreased by 32%[27].

More face-to-face nursing consultations occurred in 2019 compared with 2020, and the same was observed regarding face-to-face medical consultations. However, regarding cancer screening, in 2020 compared with 2019, fewer women got mammographies in the previous 2 years, fewer women updated their Pap smears, and fewer individuals got their colorectal cancer screening[29].

Portugal was not the only country whose health services were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Other European and non-European countries also suffered adjustments and had similar results to those observed in Portugal in primary care health services during COVID-19[30]. In this regard, some authors have proposed lessons on the COVID-19 pandemic for primary care professionals worldwide[31]. The main aspects that these authors consider essential for health services to learn and adapt are: (1) Rapidly changing and innovating by redirecting patient flow like primary care; (2) Maintaining access to primary care and managing all health problems that impact the local population; and (3) Collecting and disseminating information that is sufficiently fitted for the purpose[31].

The alterations in the operation of laboratories were studied mainly in the laboratories dedicated to diagnosing malignant pathologies.

In the cytopathology laboratories of 23 countries (including Portugal), the number of samples analyzed during 2020 compared with the same period in 2019 was reduced by 45.3%[32]. While the number of samples from the cervicovaginal tract, thyroid, and anorectal region decreased significantly, and the percentage of samples from the urinary tract, serous cavities, breast, lymph nodes, respiratory tract, salivary glands, central nervous system, gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, liver, and biliary tract increased[32].

Also, lab facilities were adapted to work in COVID-19-free environments. Glasbey et al[33] compared hospitals with and without COVID-19-free surgical pathways to investigate if implementing these pathways could be associated with lower postoperative pulmonary complication rates. This study demonstrated that COVID-19-free surgical pathways should be established within available resources to provide safer elective cancer surgery during current and future COVID-19 outbreaks. As health providers resume elective cancer surgery, they should prevent harm by investing in dedicated COVID-19-free surgical pathways tailored to local resources[33].

The SARS-CoV-2 infection is frequently associated with acute liver injury (ALI), evidenced by increased transaminases in individuals with and without prior liver disease. Elevated transaminases affected up to 50% of SARS-CoV-2 infected subjects and correlated with the severity of the disease[34].

Transaminase elevation during COVID-19 is mostly mild and reversible (i.e., < 5 times higher than the normal limit). Severe ALI is uncommon, occurring in 0.1% on admission and 2% during hospitalization, with alanine aminotransferase (ALT) values 20 times higher than the normal limit. These individuals had abnormal liver tests before being hospitalized[35].

ALI reflected by increased transaminases and bilirubin was related to disease severity and poor outcome of COVID-19[36]. Increases in gamma glutamyl transferase (γGT) and alkaline phosphatase (AP), also liver-related enzymes, are less observed and found more frequently in the later course of the disease. In contrast, moderate increases in aspartate aminotransferase (AST), ALT, and bilirubin are very common features in COVID-19[37].

Cholangiopathy, which is focal or extensive damage to bile ducts due to an impaired blood supply, has been reported as a late complication of severe COVID-19, and some persons have developed progressive biliary injury and liver failure[38,39]. In a study with 2047 patients hospitalized for COVID-19, 12 (approximately 0.58%) with severe COVID-19 developed a syndrome of cholangiopathy characterized by cholestasis and biliary tract abnormalities[38]. The mean time from COVID-19 diagnosis to cholangiopathy was 118 d. Imaging findings included inflammation, beading, stricturing, and dilation of the biliary tree.

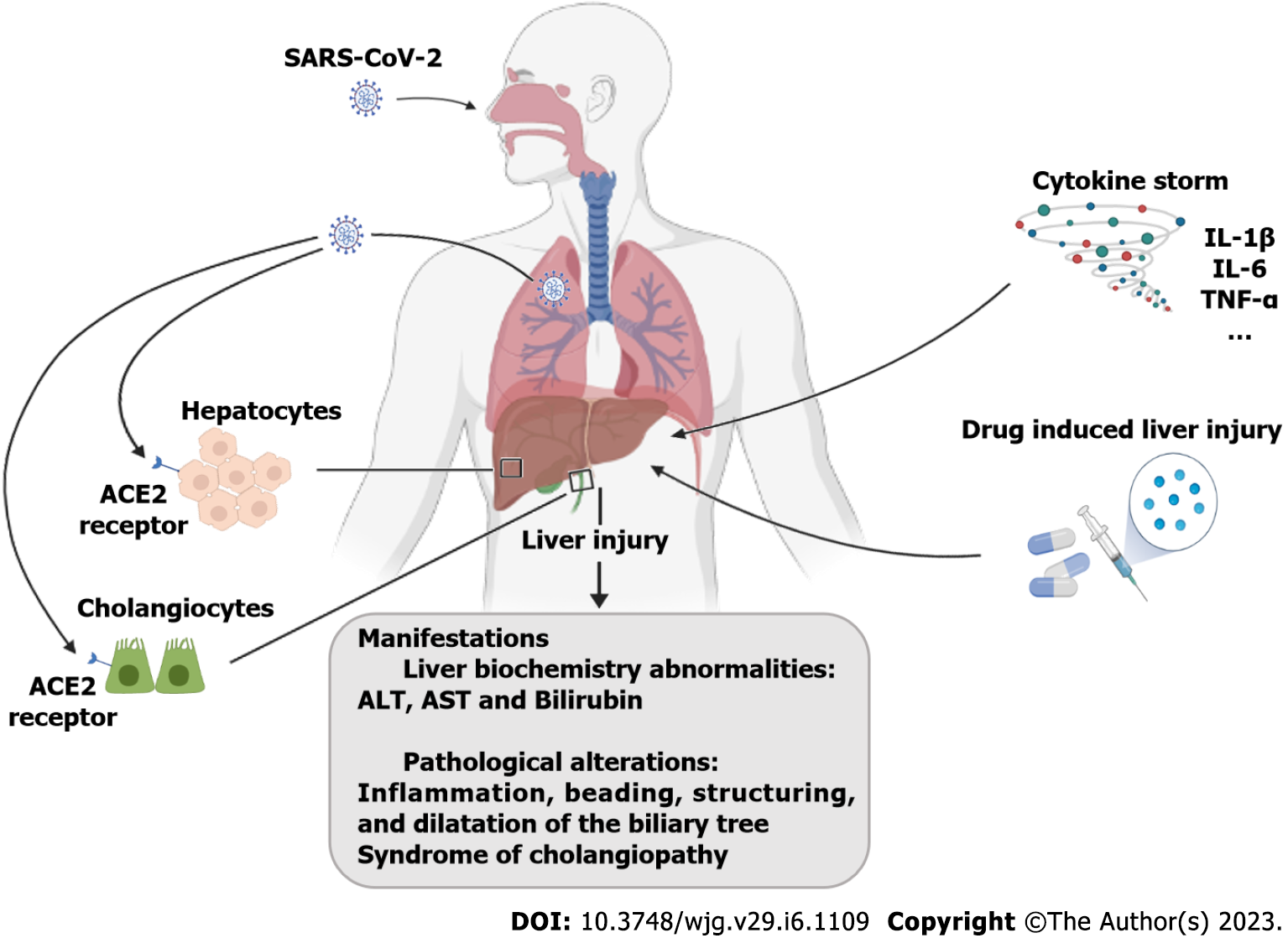

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor and the SARS-CoV-2 co-receptor transmembrane serine protease 2 seem to be the key host receptors for this virus and are expressed on diverse liver cells such as hepatocytes, immune cells, cholangiocytes, and liver progenitor cells. The levels of ACE2 are very low in liver cells, accounting for 2.6% of the total number of cells, but it is highly expressed in bile duct cells (59.7%)[40] (Figure 2).

The liver may undergo several injuries during the infection period. According to several authors, these aggressions may result from: (1) A direct virus attack on the different types of liver cells; (2) A magnified immune response (cytokine storm); and (3) Toxicity of the drugs used to treat COVID-19 symptoms. Whether one or the sum of these insults contributes to liver disruption has yet to be clarified. The ‘cytokine storm’ that occurs in COVID-19 is common to other viral infections and involves a massive acute phase reaction that results from the release of huge amounts of proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-1, tumor necrosis factor, and IL-6, as well as an increased concentration of C reactive protein and ferritin. The bulk of these cytokines is released by macrophages and monocytes, assumed to be the main players of the ‘cytokine storm’ that occurs in SARS-CoV-2 infection[41,42] (Figure 2).

Whether individuals with chronic liver disease (CLD) are more susceptible to COVID-19 is uncertain. CLD, in the absence of immunosuppressive therapy, is not known to be associated with an increased risk of acquiring COVID-19[36]. However, the liver may be susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 because of ACE2 receptors in the biliary and liver epithelial cells[40].

Data have suggested that preexisting liver disease was associated with worse outcomes in individuals with COVID-19. In a study of 2780 persons with COVID-19, those with CLD (n = 250) had higher rates of mortality as compared with those without liver disease (12% vs. 4%; risk ratio: 2.8, 95%CI: 1.9-4.0)[9,43,44]. Similarly, research carried out in Bangladesh on the relation of comorbidities, the severity of COVID-19, and hospitalization found that 43.6% of the individuals with HD (n = 39 in a sample of 1025) had more serious, i.e., moderate to severe, symptoms of COVID-19[9]; in another study in the same country on the relation of comorbidities and health outcomes in COVID-19 persons, the authors concluded that several comorbidities, including liver diseases, influence the severity of outcomes and fatality in these individuals[6].

Subsequently, a large French retrospective cohort of > 259000 individuals with COVID-19, including > 15000 with preexisting CLD, demonstrated that those with decompensated cirrhosis were at an increased adjusted risk for COVID-19 mortality[45].

Acute-on-chronic liver failure is also well recognized, being reported in up to 12%–50% of people with decompensated cirrhosis and COVID-19. Although acute hepatic malfunction induced by the SARS-CoV-2 virus may aggravate decompensated cirrhosis, in most cases, this liver aggravation did not contribute to the death of individuals, which occurred mostly due to respiratory failure (71%), followed by liver-related complications (19%)[44].

CLD is considered a serious problem worldwide. Liver injuries like cirrhosis, chronic viral hepatitis, alcohol-related liver disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and autoimmune hepatitis affect approximately 50 thousand people in Portugal, most of which are still undiagnosed[46]. Therefore, it is important to carefully evaluate how different existing liver diseases influence liver damage in persons with COVID-19[47,48].

Individuals with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) treated with nucleoside analogs for long periods are in a phase of immune tolerance. Therefore, the virus that causes hepatitis is inhibited. However, when infected with SARS-CoV-2, they can suffer severe liver injury[48].

Previous studies[47,48] have shown that for persons with hepatitis B undergoing antiviral therapy, stopping drug administration may lead to reactivation and replication of the hepatitis B virus (HBV) after treatment against SARS-CoV-2 infection is done. It has also been previously reported[47,48] that CHB patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 may take longer to clear the virus from their bodies. Zha et al[49] found a correlation between chronic HBV infection and the time required to eliminate SARS-CoV-2 from the individual. This association may have to do with T-cell dysfunction in people with chronic HBV infection fighting other viruses, but the link between them requires future investigations.

Other clinical studies have noted that the combination of lopinavir and ritonavir in the treatment of individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 may increase liver damage in those with hepatitis B or hepatitis C[47], so the use of these drugs in the treatment of COVID-19 may promote or worsen liver injury in people with preexisting liver disease[47,48].

Another risk factor that may be related to disease severity and mortality and is common in persons with COVID-19 is dysfunction in the immune system[47,48]. In persons with autoimmune hepatitis who have been infected with SARS-CoV-2, special attention should be paid to the effect of glucocorticoid administration on the prognosis of the disease[47,50]. Considering the high level of ACE2 receptor expression in bile duct cells, individuals with cholangitis infected with SARS-CoV-2 may see their cholestasis worsen, resulting in increased levels of AP and γGT[48]. Moreover, persons with cirrhosis and liver cancer with systemic immunodeficiency might be more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection, as their immune function is relatively lower[47,50].

For individuals with COVID-19 and mildly abnormal liver function, the administration of anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective drugs is generally not required[48]. Still, if necessary, the initial disease should be treated with antiviral and supportive drugs that inhibit viral replication, reduce inflammation, and enhance immunity. Additionally, the pre-emptive application of liver-protective and liver enzyme-lowering drugs is not recommended[47].

In people with COVID-19 and acute liver damage, clinicians should analyze and judge the most probable cause of liver injury and then take the appropriate action[47,48]. Routinely, these persons should be treated with anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective drugs, and jaundice-reducing agents such as polyene phosphatidylcholine, glycyrrhizic acid, bicyclol, and vitamin E[48]. In critically ill patients, the therapy should be chosen according to liver function injury, the types of drugs administered should not be more than two, and the dosage should not be too high to avoid worsening liver damage and drug interactions[49].

In persons with COVID-19 suspected of having liver damage caused by drugs, stopping or reducing the amount of the drug should be considered. Besides that, liver function indicators should be closely monitored to prevent acute liver failure[47,48]. Respiratory and circulatory support should be reinforced in individuals with critical and severe COVID-19 disease with liver damage since the clinical status should be caused by cytokine storms and microcirculation ischemia and hypoxia[47]. If necessary, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation should be performed to improve the blood oxygen saturation of patients[47].

In this way, control and prevention of the inflammatory response in the early phase of the disease not only helps to reduce nonspecific inflammation in the liver but also prevents the occurrence of a systemic inflammatory response as a way to mitigate the likelihood of mild disease developing into severe or critical illness[47,48].

The main drugs used to treat COVID-19 in individuals with severe or strong symptoms, i.e., hydroxychloroquine[51,52], lopinavir/ritonavir[53], and remdesivir[54-58], have adverse effects in the liver (Table 2). Such effects limit the use of these drugs in persons with previous liver diseases who may experience an aggravation of COVID-19 symptoms (as explained before).

| Drug(s) | Mechanism of action | Adverse effects on the liver | Ref. |

| Hydroxychloroquine | Increases intracellular pH and inhibits lysosomal activity in antigen-presenting cells | Liver failure | [51,52] |

| Lopinavir/Ritonavir | Inhibition of 3-chymotrypsin-like protease | Hepatoxicity | [53] |

| Remdesivir | Inhibits viral transcription and replication by blocking the RNA polymerase enzyme | Increased aminotransferase levels | [54-57,70] |

The impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the liver and the hypothesis that having liver injury may represent a risk factor for the worsening of COVID-19 prognosis have been addressed by several authors[47,48,59].

In Portugal, an epidemiological study by Tenreiro et al[60], in a sample of 35117 individuals with COVID-19, demonstrated that the risk of hospitalization increases with the presence of comorbidities and that preexisting pathologies, such as CLDs, are associated with worse prognosis in people with COVID-19 (Table 1). In agreement, Froes et al[61] (2020) and Ricoca Peixoto et al[62] (2021) observed that the presence of concurrent comorbidities is significantly associated with negative outcomes when the person is infected with SARS-CoV-2 (Table 1).

In the different studies (Table 1), it was also possible to observe that in the Portuguese population, the risk of hospitalization and lethality associated with COVID-19 in infected individuals is higher in males and increases with age[60-64]. Furthermore, Musa[65] also noted that people at high risk of severe COVID-19 are generally older and/or have associated complications such as diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and liver disease.

However, the existing literature has shown contradictory data. Although some reports have shown that persons with comorbidities, such as liver failure, had longer hospitalization lengths and were at a higher risk of progressing to severe disease[58,66], which is in line with the data found in Portuguese individuals, other studies have demonstrated that the COVID-19-related liver injuries are usually temporary and mild, with minor clinical significance[59,67].

Liver biochemical indicators, mainly shown by abnormal ALT and AST levels complemented by a slight increase in total bilirubin levels and prolonged prothrombin time, have also been used as a predictor of the severity and prognosis of COVID-19 patients[47,59,68,69].

In a study performed by Guan et al[68] (2020), which included 1099 patients, elevated AST levels were observed in 18.2% of patients with non-severe disease and 39.4% with severe disease. In addition, the proportion of patients with abnormal ALT in severe cases (28.1%) was higher than that in mild cases (19.8%)[68]. Other studies, however, have found different results. Wang et al[70] and Wu et al[50] reported no significant differences in liver function tests when comparing severe and mild/moderate patients.

In the Portuguese literature, there is still scarce information regarding the global etiology of preexisting liver disease in individuals with COVID-19. Garrido et al[59], in a study of 317 individuals with COVID-19 at the University Hospital Center of Porto, observed that at the time of hospitalization, 50.3% of patients had abnormal changes in liver enzymes, with 41.5% showing elevated levels of aminotransferases. AST and AP were associated with the severity of COVID-19, intensive care unit (ICU) admission and increased mortality. In contrast, ALT and γGT were associated with patient admission to the ICU[59]. In the same study, the authors reported that of the 14 patients with CLD, 21.4% had a critical level of COVID-19, the average duration of disease was 36.6 d, hospitalization 11.5 d, and mortality 28.6%, increasing to 66.7% in patients with liver cirrhosis[59].

Portugal participated in the European study from the European Hematology Association Survey (EPICOVIDEHA) that aimed to investigate the characteristics of hematological malignancies in individuals developing COVID-19 and analyzed predictors of mortality[71]. The authors concluded that increased age, active disease, chronic cardiopathy, liver disease, renal impairment, smoking history, and ICU were significantly associated with higher mortality[71].

Recently, we published a study on the Portuguese population, with more than 2000 participants, reporting the medical and legal implications of COVID-19 in life habits[24]. We observed that the subjects increased alcohol consumption, a change that can contribute to liver diseases. On the other hand, we also analyzed all participants' comorbidities, and none indicated having a liver disease (unpublished results). It is possible that in some cases, the individuals do not even know that they have liver malfunction, or the liver disease is discovered after the SARS-CoV-2 infection and treatment.

However, as concluded in other reports[58,59,68], it remains unclear whether these changes in laboratory tests are associated with a worse prognosis in individuals with COVID-19 because the cause of these alterations could be explained by several factors like the virus or the percussion of a severe inflammatory response from a liver injury such as hypoxic hepatitis, drug toxicity, immune response, and alterations in the gut vascular barrier and microbiota[47,48,59].

We surveyed several databases and screened several papers to review the clinical manifestations and outcomes of Portuguese individuals with COVID-19 and liver injury. However, only six studies reported original observational and retrospective research on the Portuguese adult population concerning liver-associated clinical manifestations or outcomes and COVID-19.

Because of the relatively small number of articles analyzed in this review, further studies were considered to develop and elaborate on the results obtained. Data from the Portuguese NHS on COVID-19 was also included. In this second round of literature search, we found information about the implications of COVID-19 in healthcare. Therefore, we broadened the scope of this review, although this was not initially planned.

We examined topics essential to understanding the relationship between COVID-19, liver injury, and patients’ clinical outcomes. We discussed: (1) How COVID-19 affected health care and clinical practice in Portugal; (2) The relationship between COVID-19 and liver diseases; (3) Hepatic conditions that affect the treatment of COVID-19; and (4) What is known regarding liver diseases and COVID-19 in Portuguese individuals.

Our results demonstrated the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic in Portugal's health care and clinical practice. We observed that the number of face-to-face consultations decreased during the pandemic, specifically, during the first semester, of 2020, compared with the same period of the last 2 years (2018/2019). However, virtual medical assistance, i.e., medical and nurse teleconsultations, increased. Besides these changes in medical appointments, we also observed adjustments in the activity of diagnostic laboratories. A European study involving Portugal demonstrated that the percentage of analyzed samples increased during the pandemic, specifically from the liver, urinary tract, serous cavities, breast, lymph nodes, respiratory tract, and others. On the contrary, the percentage of analyzed samples of the cervicovaginal tract, thyroid, and anorectal region decreased[32].

While exploring the role of liver injury and COVID-19, we observed that COVID-19 affects liver activity, changing the enzymatic activity[37]. These enzymatic alterations were observed in half of the infected individuals[34]. On the other hand, preexisting liver disease was associated with worse outcomes in persons with COVID-19. For this reason, in Portugal, having a liver disease (chronic disease) was enough to be included in priority groups for vaccination during the first campaign of the Portuguese NHS.

The liver and COVID-19 are interrelated. On the one hand, liver function affects COVID-19 status. On the other hand, drugs such as lopinavir, ritonavir, hydroxychloroquine, and remdesivir, used to treat COVID-19, may cause adverse effects on the liver and affect its function (Table 1).

According to our search, the clinical outcome in Portuguese individuals with COVID-19 was aggravated by liver injury, old age, and other comorbidities leading to treatment in intensive care and increased mortality.

COVID-19 was a pandemic that had many implications for people’s health, life quality, and lifestyle and their access to public or “social” services, such as primary healthcare services. The global dimension of COVID-19 consequences is almost unmeasurable. However, our lives have changed, and these alterations may be permanent. Not so much time ago, before the COVID-19 pandemic, teleconsultations were unthinkable. During the pandemic, telemedicine became a form of access to medical assistance.

Furthermore, all health systems had to adapt during COVID-19, prioritizing healthcare. According to this evidence, we conclude that societies should define strategies to be implemented during pandemic situations to ensure that all individuals have guaranteed access to health care (Figure 3). In Portugal, we observed that the alterations that occurred in the healthcare system during the pandemic seem to have been effective in providing care to the population.

Concerning the relationship between liver diseases and COVID-19, we conclude that COVID-19 may alter the function of the liver. The worsening of the COVID-19 status depends on the age of the individuals and the presence of other comorbidities, albeit the papers analyzed in this review do not discuss if the liver function is age-dependent. Moreover, the drugs used to treat COVID-19 have adverse effects on the liver and affect liver function.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) may be asymptomatic or cause mild to severe symptoms exacerbated by preexisting health conditions like liver diseases. However, the relation between hepatic diseases and the effect and prognosis of COVID-19 individuals is unclear, and information concerning the Portuguese population is scarce.

To understand how hepatic disorders may have been affected by COVID-19 and how this infection impacted the Portuguese healthcare system.

To investigate the association between COVID-19 and liver diseases and their impact on the prognosis of patients and explore the effect of COVID-19 on healthcare systems.

A review of the relevant literature was performed.

People with liver diseases who were COVID-19-positive had a worse prognosis than individuals without hepatic diseases. Due to COVID-19, most countries altered the normal activity of healthcare systems, increasing teleconsultations.

The interaction between liver diseases and COVID-19 in people's prognosis is unclear, but there is evidence of its existence. As observed in other countries, the normal activity of the national healthcare system in Portugal was modified due to the pandemic situation created by COVID-19.

To promote the development of studies about the interaction and relation between liver diseases and COVID-19 and generate critical thinking about how healthcare systems should function in case of a pandemic.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Portugal

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Baruch J, United States; Ganguli S, Bangladesh S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Alimohamadi Y, Sepandi M, Taghdir M, Hosamirudsari H. Determine the most common clinical symptoms in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Prev Med Hyg. 2020;61:E304-E312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW; the Northwell COVID-19 Research Consortium, Barnaby DP, Becker LB, Chelico JD, Cohen SL, Cookingham J, Coppa K, Diefenbach MA, Dominello AJ, Duer-Hefele J, Falzon L, Gitlin J, Hajizadeh N, Harvin TG, Hirschwerk DA, Kim EJ, Kozel ZM, Marrast LM, Mogavero JN, Osorio GA, Qiu M, Zanos TP. Presenting Characteristics, Comorbidities, and Outcomes Among 5700 Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 in the New York City Area. JAMA. 2020;323:2052-2059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6024] [Cited by in RCA: 6518] [Article Influence: 1303.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Callender LA, Curran M, Bates SM, Mairesse M, Weigandt J, Betts CJ. The Impact of Pre-existing Comorbidities and Therapeutic Interventions on COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zhang H, Han H, He T, Labbe KE, Hernandez AV, Chen H, Velcheti V, Stebbing J, Wong KK. Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of COVID-19-Infected Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113:371-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 36.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | WHO. Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020; 2020. [cited 19 August 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020. |

| 6. | Sharif N, Opu RR, Ahmed SN, Sarkar MK, Jaheen R, Daullah MU, Khan S, Mubin M, Rahman H, Islam F, Haque N, Islam S, Khan FB, Ayman U, Shohael AM, Dey SK, Talukder AA. Prevalence and impact of comorbidities on disease prognosis among patients with COVID-19 in Bangladesh: A nationwide study amid the second wave. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2021;15:102148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fathi M, Vakili K, Sayehmiri F, Mohamadkhani A, Hajiesmaeili M, Rezaei-Tavirani M, Eilami O. The prognostic value of comorbidity for the severity of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis study. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0246190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mauskopf J, Klesse M, Lee S, Herrera-Taracena G. The burden of influenza complications in different high-risk groups: a targeted literature review. J Med Econ. 2013;16:264-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ganguli S, Howlader S, Dey K, Barua S, Islam MN, Aquib TI, Partho PB, Chakraborty RR, Barua B, Hawlader MDH, Biswas PK. Association of comorbidities with the COVID-19 severity and hospitalization: A study among the recovered individuals in Bangladesh. Int J Health Sci (Qassim). 2022;16:30-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Martins A, Mouro M, Caldas J, Silva-Pinto A, Santos AS, Xerinda S, Ferreira A, Figueiredo P, Sarmento A, Santos L. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of critically ill COVID-19 patients admitted to an Infectious Diseases Intensive Care Unit in Portugal. Crit Care & Shock. 2021;24. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Perez Duque M, Saad NJ, Lucaccioni H, Costa C, McMahon G, Machado F, Balasegaram S, Sá Machado R. Clinical and hospitalisation predictors of COVID-19 in the first month of the pandemic, Portugal. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0260249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sá R, Pinho-Bandeira T, Queiroz G, Matos J, Ferreira JD, Rodrigues PP. COVID-19 and Its Symptoms’ Panoply: A Case-Control Study of 919 Suspected Cases in Locked-Down Ovar, Portugal. Port J Pub Health. 2020;38:151-158. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Silva RF, Mendonça L, Pereira L, Beco A. Case series of COVID-19 in chronic kidney disease patients under peritoneal dialysis at a northern Portuguese center. Port J Nephrol Hypert. 2022;36:31-34. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Silva FAFD, Brito BB, Santos MLC, Marques HS, Silva Júnior RTD, Carvalho LS, Vieira ES, Oliveira MV, Melo FF. COVID-19 gastrointestinal manifestations: a systematic review. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2020;53:e20200714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lopes-Pacheco M, Silva PL, Cruz FF, Battaglini D, Robba C, Pelosi P, Morales MM, Caruso Neves C, Rocco PRM. Pathogenesis of Multiple Organ Injury in COVID-19 and Potential Therapeutic Strategies. Front Physiol. 2021;12:593223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 29.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Elias C, Feteira-Santos R, Camarinha C, de Araújo Nobre M, Costa AS, Bacelar-Nicolau L, Furtado C, Nogueira PJ. COVID-19 in Portugal: a retrospective review of paediatric cases, hospital and PICU admissions in the first pandemic year. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2022;6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Garrido I, Liberal R, Macedo G. Review article: COVID-19 and liver disease-what we know on 1st May 2020. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52:267-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Duarte Silva R. Ministra confirma primeiro caso positivo de coronavírus em Portugal. Jornal Expresso 2020. [cited 19 August 2021]. Available from: https://expresso.pt/sociedade/2020-03-02-Ministra-confirma-primeiro-caso-positivo-de-coronavirus-em-Portugal. |

| 19. | Harzing AW. Publish or Perish 2007. [cited 19 August 2021]. Available from: https://harzing.com/resources/publish-or-perish. |

| 20. | Ribeiro Queirós P, Caeiro D, Ponte M, Guerreiro C, Silva M, Pipa S, Rios AL, Adrião D, Neto R, Teixeira P, Silva G, Ferreira ND, Castelões P, Braga P. Fighting the pandemic with collaboration at heart: Report from cardiologists in a COVID-19-dedicated Portuguese intensive care unit. Rev Port Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2021;40:923-928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Ranhel D, Ribeiro A, Batista J, Pessanha M, Cristovam E, Duarte A, Dias A, Coelho L, Monteiro F, Freire P, Veríssimo C, Sabino R, Toscano C. COVID-19-Associated Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis in the Intensive Care Unit: A Case Series in a Portuguese Hospital. J Fungi (Basel). 2021;7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Palavras MJ, Faria C, Fernandes P, Lagarto A, Ponciano A, Alçada F, Banza MJ. The Impact of the Third Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Elderly and Very Elderly Population in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Portugal. Cureus. 2022;14:e22653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Poppe M, Aguiar B, Sousa R, Oom P. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children's Health in Portugal: The Parental Perspective. Acta Med Port. 2021;34:355-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Fernandes S, Sosa-Napolskij M, Lobo G, Silva I. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Portuguese population: Consumption of alcohol, stimulant drinks, illegal substances, and pharmaceuticals. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0260322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Order 3301-A/2020 of the Minister of Health on March 15. Portuguese Ministry of Health Lisbon. Port Rep D 2020: 2-2. [cited 19 August 2021]. Available from: https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/despacho/3301-a-2020-130273596. |

| 26. | Vieira PA, Barros PJ, Caseiro T, Rodrigues N, Arcanjo J. Efeitos de uma pandemia numa unidade de cuidados de saúde primários e sua população: um estudo retrospetivo. Rev Port Med Ger Fam. 2021;37:393-406. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 27. | SNS. 2022. [cited 6 September 2022]. Available from: https://transparencia.sns.gov.pt. |

| 28. | ERS. Impacto da pandemia COVID no Sistema de Saúde–período de março a junho de 2020. Entidade Reguladora da Saúde (Health Regulatory Entity): Portugal 2020: 46. [cited 19 August 2021]. Available from: https://www.ers.pt/media/3487/im-impacto-covid-19.pdf. |

| 29. | Machado DMR, Almeida AdDLD, Brás MAM, Anes EMJ. Impacto da pandemia, por SARS-COV-2, no acesso aos cuidados de saúde primarios. Revista INFAD De Psicología. Intern J Dev Educ Psyc. 2021;3:95-100. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 30. | Haldane V, Zhang Z, Abbas RF, Dodd W, Lau LL, Kidd MR, Rouleau K, Zou G, Chao Z, Upshur REG, Walley J, Wei X. National primary care responses to COVID-19: a rapid review of the literature. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e041622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Rawaf S, Allen LN, Stigler FL, Kringos D, Quezada Yamamoto H, van Weel C; Global Forum on Universal Health Coverage and Primary Health Care. Lessons on the COVID-19 pandemic, for and by primary care professionals worldwide. Eur J Gen Pract. 2020;26:129-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 40.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Vigliar E, Cepurnaite R, Alcaraz-Mateos E, Ali SZ, Baloch ZW, Bellevicine C, Bongiovanni M, Botsun P, Bruzzese D, Bubendorf L, Büttner R, Canberk S, Capitanio A, Casadio C, Cazacu E, Cochand-Priollet B, D'Amuri A, Eloy C, Engels M, Fadda G, Fontanini G, Fulciniti F, Hofman P, Iaccarino A, Ieni A, Jiang XS, Kakudo K, Kern I, Kholova I, Liu C, Lobo A, Lozano MD, Malapelle U, Maleki Z, Michelow P, Musayev J, Özgün G, Oznur M, Peiró Marqués FM, Pisapia P, Poller D, Pyzlak M, Robinson B, Rossi ED, Roy-Chowdhuri S, Saieg M, Savic Prince S, Schmitt FC, Javier Seguí Iváñez F, Štoos-Veić T, Sulaieva O, Sweeney BJ, Tuccari G, van Velthuysen ML, VanderLaan PA, Vielh P, Viola P, Voorham R, Weynand B, Zeppa P, Faquin WC, Pitman MB, Troncone G. Global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cytopathology practice: Results from an international survey of laboratories in 23 countries. Cancer Cytopathol. 2020;128:885-894. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Glasbey JC, Nepogodiev D, Simoes JFF, Omar O, Li E, Venn ML, Pgdme, Abou Chaar MK, Capizzi V, Chaudhry D, Desai A, Edwards JG, Evans JP, Fiore M, Videria JF, Ford SJ, Ganly I, Griffiths EA, Gujjuri RR, Kolias AG, Kaafarani HMA, Minaya-Bravo A, McKay SC, Mohan HM, Roberts KJ, San Miguel-Méndez C, Pockney P, Shaw R, Smart NJ, Stewart GD, Sundar Mrcog S, Vidya R, Bhangu AA; COVIDSurg Collaborative. Elective Cancer Surgery in COVID-19-Free Surgical Pathways During the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic: An International, Multicenter, Comparative Cohort Study. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:66-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 42.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, Yan W, Yang D, Chen G, Ma K, Xu D, Yu H, Wang H, Wang T, Guo W, Chen J, Ding C, Zhang X, Huang J, Han M, Li S, Luo X, Zhao J, Ning Q. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ. 2020;368:m1091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2289] [Cited by in RCA: 2550] [Article Influence: 510.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 35. | Sobotka LA, Esteban J, Volk ML, Elmunzer BJ, Rockey DC; North American Alliance for the Study of Digestive Manifestation of COVID-19*. Acute Liver Injury in Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67:4204-4214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Zhang SS, Dong L, Wang GM, Tian Y, Ye XF, Zhao Y, Liu ZY, Zhai JY, Zhao ZL, Wang JH, Zhang HM, Li XL, Wu CX, Yang CT, Yang LJ, Du HX, Wang H, Ge QG, Xiu DR, Shen N. Progressive liver injury and increased mortality risk in COVID-19 patients: A retrospective cohort study in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:835-853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Bernal-Monterde V, Casas-Deza D, Letona-Giménez L, de la Llama-Celis N, Calmarza P, Sierra-Gabarda O, Betoré-Glaria E, Martínez-de Lagos M, Martínez-Barredo L, Espinosa-Pérez M, M Arbones-Mainar J. SARS-CoV-2 Infection Induces a Dual Response in Liver Function Tests: Association with Mortality during Hospitalization. Biomedicines. 2020;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Faruqui S, Okoli FC, Olsen SK, Feldman DM, Kalia HS, Park JS, Stanca CM, Figueroa Diaz V, Yuan S, Dagher NN, Sarkar SA, Theise ND, Kim S, Shanbhogue K, Jacobson IM. Cholangiopathy After Severe COVID-19: Clinical Features and Prognostic Implications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:1414-1425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Meersseman P, Blondeel J, De Vlieger G, van der Merwe S, Monbaliu D; Collaborators Leuven Liver Transplant program. Secondary sclerosing cholangitis: an emerging complication in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47:1037-1040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Chai X, Hu L, Zhang Y, Han W, Lu Z, Ke A, Zhou J, Shi G, Fang N, Fan J. Specific ACE2 expression in cholangiocytes may cause liver damage after 2019-nCoV infection. 2020 Preprint. Available from: biorxiv:931766. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 41. | Pedersen SF, Ho YC. SARS-CoV-2: a storm is raging. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:2202-2205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 869] [Cited by in RCA: 853] [Article Influence: 170.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Abstracts of Presentations at the Association of Clinical Scientists 143(rd) Meeting Louisville, KY May 11-14,2022. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2022;52:511-525. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 43. | Singh S, Khan A. Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Among Patients With Preexisting Liver Disease in the United States: A Multicenter Research Network Study. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:768-771.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 270] [Article Influence: 54.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Marjot T, Moon AM, Cook JA, Abd-Elsalam S, Aloman C, Armstrong MJ, Pose E, Brenner EJ, Cargill T, Catana MA, Dhanasekaran R, Eshraghian A, García-Juárez I, Gill US, Jones PD, Kennedy J, Marshall A, Matthews C, Mells G, Mercer C, Perumalswami PV, Avitabile E, Qi X, Su F, Ufere NN, Wong YJ, Zheng MH, Barnes E, Barritt AS 4th, Webb GJ. Outcomes following SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with chronic liver disease: An international registry study. J Hepatol. 2021;74:567-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 399] [Cited by in RCA: 384] [Article Influence: 96.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Mallet V, Beeker N, Bouam S, Sogni P, Pol S; Demosthenes research group. Prognosis of French COVID-19 patients with chronic liver disease: A national retrospective cohort study for 2020. J Hepatol. 2021;75:848-855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | APEF. Médicos alertam para a importância de diagnóstico precoce das Hepatites (Doctors warn about the importance of early diagnosis of hepatitis), Doctors communication 2022. [cited 6 September 2022]. Available from: https://apef.com.pt/medicos-alertam-para-a-importancia-de-diagnostico-precoce-das-hepatites. |

| 47. | Tian D, Ye Q. Hepatic complications of COVID-19 and its treatment. J Med Virol. 2020;92:1818-1824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Wu J, Song S, Cao HC, Li LJ. Liver diseases in COVID-19: Etiology, treatment and prognosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:2286-2293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 49. | Zha L, Li S, Pan L, Tefsen B, Li Y, French N, Chen L, Yang G, Villanueva EV. Corticosteroid treatment of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Med J Aust. 2020;212:416-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 45.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Wu J, Li W, Shi X, Chen Z, Jiang B, Liu J, Wang D, Liu C, Meng Y, Cui L, Yu J, Cao H, Li L. Early antiviral treatment contributes to alleviate the severity and improve the prognosis of patients with novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19). J Intern Med. 2020;288:128-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 43.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Zhou D, Dai SM, Tong Q. COVID-19: a recommendation to examine the effect of hydroxychloroquine in preventing infection and progression. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2020;75:1667-1670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 321] [Cited by in RCA: 344] [Article Influence: 68.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Lacout A, Perronne C, Lounnas V. Hydroxychloroquine in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:881-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Dong L, Hu S, Gao J. Discovering drugs to treat coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Drug Discov Ther. 2020;14:58-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 834] [Cited by in RCA: 873] [Article Influence: 174.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, Mehta AK, Zingman BS, Kalil AC, Hohmann E, Chu HY, Luetkemeyer A, Kline S, Lopez de Castilla D, Finberg RW, Dierberg K, Tapson V, Hsieh L, Patterson TF, Paredes R, Sweeney DA, Short WR, Touloumi G, Lye DC, Ohmagari N, Oh MD, Ruiz-Palacios GM, Benfield T, Fätkenheuer G, Kortepeter MG, Atmar RL, Creech CB, Lundgren J, Babiker AG, Pett S, Neaton JD, Burgess TH, Bonnett T, Green M, Makowski M, Osinusi A, Nayak S, Lane HC; ACTT-1 Study Group Members. Remdesivir for the Treatment of Covid-19 - Final Report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1813-1826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5711] [Cited by in RCA: 5119] [Article Influence: 1023.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Grein J, Ohmagari N, Shin D, Diaz G, Asperges E, Castagna A, Feldt T, Green G, Green ML, Lescure FX, Nicastri E, Oda R, Yo K, Quiros-Roldan E, Studemeister A, Redinski J, Ahmed S, Bernett J, Chelliah D, Chen D, Chihara S, Cohen SH, Cunningham J, D'Arminio Monforte A, Ismail S, Kato H, Lapadula G, L'Her E, Maeno T, Majumder S, Massari M, Mora-Rillo M, Mutoh Y, Nguyen D, Verweij E, Zoufaly A, Osinusi AO, DeZure A, Zhao Y, Zhong L, Chokkalingam A, Elboudwarej E, Telep L, Timbs L, Henne I, Sellers S, Cao H, Tan SK, Winterbourne L, Desai P, Mera R, Gaggar A, Myers RP, Brainard DM, Childs R, Flanigan T. Compassionate Use of Remdesivir for Patients with Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2327-2336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1926] [Cited by in RCA: 1884] [Article Influence: 376.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Lo MK, Jordan R, Arvey A, Sudhamsu J, Shrivastava-Ranjan P, Hotard AL, Flint M, McMullan LK, Siegel D, Clarke MO, Mackman RL, Hui HC, Perron M, Ray AS, Cihlar T, Nichol ST, Spiropoulou CF. GS-5734 and its parent nucleoside analog inhibit Filo-, Pneumo-, and Paramyxoviruses. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 280] [Cited by in RCA: 356] [Article Influence: 44.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Sheahan TP, Sims AC, Graham RL, Menachery VD, Gralinski LE, Case JB, Leist SR, Pyrc K, Feng JY, Trantcheva I, Bannister R, Park Y, Babusis D, Clarke MO, Mackman RL, Spahn JE, Palmiotti CA, Siegel D, Ray AS, Cihlar T, Jordan R, Denison MR, Baric RS. Broad-spectrum antiviral GS-5734 inhibits both epidemic and zoonotic coronaviruses. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1011] [Cited by in RCA: 1126] [Article Influence: 160.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Wang Y, Liu S, Liu H, Li W, Lin F, Jiang L, Li X, Xu P, Zhang L, Zhao L, Cao Y, Kang J, Yang J, Li L, Liu X, Li Y, Nie R, Mu J, Lu F, Zhao S, Lu J, Zhao J. SARS-CoV-2 infection of the liver directly contributes to hepatic impairment in patients with COVID-19. J Hepatol. 2020;73:807-816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 353] [Cited by in RCA: 457] [Article Influence: 91.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Garrido M, Pereira Guedes T, Alves Silva J, Falcão D, Novo I, Archer S, Rocha M, Maia L, Sarmento-Castro R, Pedroto I. Impact of Liver Test Abnormalities and Chronic Liver Disease on the Clinical Outcomes of Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2021;158:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Tenreiro P, Ramalho A, Santos P. COVID-19 patients followed in Portuguese Primary Care: a retrospective cohort study based on the national case series. Fam Pract. 2022;39:52-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Froes M, Neves B, Martins B, Silva MJ. Comparison of multimorbidity in Covid-19 infected and general population in Portugal. 2020 Preprint. Available from: MedRXiv:20144378. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 62. | Ricoca Peixoto V, Vieira A, Aguiar P, Sousa P, Carvalho C, Thomas D, Abrantes A, Nunes C. Determinants for hospitalisations, intensive care unit admission and death among 20,293 reported COVID-19 cases in Portugal, March to April 2020. Euro Surveill. 2021;26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Nogueira PJ, de Araújo Nobre M, Costa A, Ribeiro RM, Furtado C, Bacelar Nicolau L, Camarinha C, Luís M, Abrantes R, Vaz Carneiro A. The Role of Health Preconditions on COVID-19 Deaths in Portugal: Evidence from Surveillance Data of the First 20293 Infection Cases. J Clin Med. 2020;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Nogueira PJ, de Araújo Nobre M, Elias C, Feteira-Santos R, Martinho AC, Camarinha C, Bacelar-Nicolau L, Costa AS, Furtado C, Morais L, Rachadell J, Pinto MP, Pinto F, Vaz Carneiro A. Multimorbidity Profile of COVID-19 Deaths in Portugal during 2020. J Clin Med. 2022;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Musa S. Hepatic and gastrointestinal involvement in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): What do we know till now? Arab J Gastroenterol. 2020;21:3-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Fan Z, Chen L, Li J, Cheng X, Yang J, Tian C, Zhang Y, Huang S, Liu Z, Cheng J. Clinical Features of COVID-19-Related Liver Functional Abnormality. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:1561-1566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 559] [Cited by in RCA: 556] [Article Influence: 111.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Xie H, Zhao J, Lian N, Lin S, Xie Q, Zhuo H. Clinical characteristics of non-ICU hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 and liver injury: A retrospective study. Liver Int. 2020;40:1321-1326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 42.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, Liu L, Shan H, Lei CL, Hui DSC, Du B, Li LJ, Zeng G, Yuen KY, Chen RC, Tang CL, Wang T, Chen PY, Xiang J, Li SY, Wang JL, Liang ZJ, Peng YX, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu YH, Peng P, Wang JM, Liu JY, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng ZJ, Qiu SQ, Luo J, Ye CJ, Zhu SY, Zhong NS; China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid-19. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708-1720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19202] [Cited by in RCA: 18878] [Article Influence: 3775.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 69. | Zhang Y, Zheng L, Liu L, Zhao M, Xiao J, Zhao Q. Liver impairment in COVID-19 patients: A retrospective analysis of 115 cases from a single centre in Wuhan city, China. Liver Int. 2020;40:2095-2103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 293] [Cited by in RCA: 310] [Article Influence: 62.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Wang Y, Zhang D, Du G, Du R, Zhao J, Jin Y, Fu S, Gao L, Cheng Z, Lu Q, Hu Y, Luo G, Wang K, Lu Y, Li H, Wang S, Ruan S, Yang C, Mei C, Wang Y, Ding D, Wu F, Tang X, Ye X, Ye Y, Liu B, Yang J, Yin W, Wang A, Fan G, Zhou F, Liu Z, Gu X, Xu J, Shang L, Zhang Y, Cao L, Guo T, Wan Y, Qin H, Jiang Y, Jaki T, Hayden FG, Horby PW, Cao B, Wang C. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1569-1578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2337] [Cited by in RCA: 2488] [Article Influence: 497.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Pagano L, Salmanton-García J, Marchesi F, Busca A, Corradini P, Hoenigl M, Klimko N, Koehler P, Pagliuca A, Passamonti F, Verga L, Víšek B, Ilhan O, Nadali G, Weinbergerová B, Córdoba-Mascuñano R, Marchetti M, Collins GP, Farina F, Cattaneo C, Cabirta A, Gomes-Silva M, Itri F, van Doesum J, Ledoux MP, Čerňan M, Jakšić O, Duarte RF, Magliano G, Omrani AS, Fracchiolla NS, Kulasekararaj A, Valković T, Poulsen CB, Machado M, Glenthøj A, Stoma I, Ráčil Z, Piukovics K, Navrátil M, Emarah Z, Sili U, Maertens J, Blennow O, Bergantim R, García-Vidal C, Prezioso L, Guidetti A, Del Principe MI, Popova M, de Jonge N, Ormazabal-Vélez I, Fernández N, Falces-Romero I, Cuccaro A, Meers S, Buquicchio C, Antić D, Al-Khabori M, García-Sanz R, Biernat MM, Tisi MC, Sal E, Rahimli L, Čolović N, Schönlein M, Calbacho M, Tascini C, Miranda-Castillo C, Khanna N, Méndez GA, Petzer V, Novák J, Besson C, Duléry R, Lamure S, Nucci M, Zambrotta G, Žák P, Seval GC, Bonuomo V, Mayer J, López-García A, Sacchi MV, Booth S, Ciceri F, Oberti M, Salvini M, Izuzquiza M, Nunes-Rodrigues R, Ammatuna E, Obr A, Herbrecht R, Núñez-Martín-Buitrago L, Mancini V, Shwaylia H, Sciumè M, Essame J, Nygaard M, Batinić J, Gonzaga Y, Regalado-Artamendi I, Karlsson LK, Shapetska M, Hanakova M, El-Ashwah S, Borbényi Z, Çolak GM, Nordlander A, Dragonetti G, Maraglino AME, Rinaldi A, De Ramón-Sánchez C, Cornely OA; EPICOVIDEHA working group. COVID-19 infection in adult patients with hematological malignancies: a European Hematology Association Survey (EPICOVIDEHA). J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14:168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 51.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |