Published online Jun 28, 2021. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i24.3668

Peer-review started: January 22, 2021

First decision: February 28, 2021

Revised: March 12, 2021

Accepted: June 3, 2021

Article in press: June 3, 2021

Published online: June 28, 2021

Processing time: 153 Days and 14.8 Hours

Eating disorders (ED) involve both the nervous system and the gastrointestinal tract. A similar double involvement is also found in disorders of the brain-gut interaction (DGBI) and symptoms are sometimes similar.

To find out where there is an association and a cause-effect relationship, we looked for the comorbidity of DGBI and ED.

A systematic review was undertaken. A literature search was performed. Inclusion criteria for the articles retained for analysis were: Observational cohort population-based or hospital-based and case-control studies, examining the relationship between DGBI and ED. Exclusion criteria were: Studies written in other languages than English, abstracts, conference presentations, letters to the Editor and editorials. Selected papers by two independent investigators were critically evaluated and included in this review.

We found 29 articles analyzing the relation between DGBI and ED comprising 13 articles on gastroparesis, 5 articles on functional dyspepsia, 7 articles about functional constipation and 4 articles on irritable bowel syndrome.

There is no evidence for a cause-effect relationship between DGBI and ED. Their common symptomatology requires correct identification and a tailored therapy of each disorder.

Core Tip: Functional gastrointestinal disorders actually defined disorders of the brain-gut interaction (DGBI) by the new Rome IV criteria share similar symptoms with eating disorders (ED). Etiology is ill defined for both disorders thou a negative impact on quality of life and a high socio-economic burden is reported. We looked for the comorbidity of DGBI and ED, in order to find out where there is an association and a cause-effect relationship.

- Citation: Stanculete MF, Chiarioni G, Dumitrascu DL, Dumitrascu DI, Popa SL. Disorders of the brain-gut interaction and eating disorders. World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27(24): 3668-3681

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v27/i24/3668.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i24.3668

Eating disorders (ED) are psychiatric disorders defined by abnormal eating habits that negatively affect a person's physical or mental health and frequently begin in late childhood or early adulthood[1]. The pathogenesis of ED is still unclear, although it has been demonstrated that both genetic and environmental factors are involved. The most frequent ED include binge ED (eating a large amount of food in a short time), anorexia nervosa (eating an extremely small quantity of food due to a fear of gaining weight in contrast with low body weight in reality), bulimia nervosa (characterized by binge eating followed by purging, an attempt to get rid of the food consumed by vomiting or taking laxatives), pica (eating non-food items like hair, paper, sharp objects, metal objects, soil or glass), night ED (delayed circadian pattern of food intake) and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (eating only within an extremely narrow repertoire of foods)[1,2].

Epidemiological studies show that in the developed world, binge eating disorder affects about 1.6% of women and 0.8% of men, anorexia nervosa about 0.4%, and bulimia about 1.3% of young women[3,4]. At some point in their lifetime, more than 4% of women have anorexia, 2% have bulimia, and 2% have a binge eating disorder. In less developed countries, the rates of ED are lower[3,4]. Females are nine times more frequent than males to suffer from ED. ED do not include obesity. Notwithstanding visible progress in the current therapeutic methods[4], ED result in more than 7000 deaths a year, covering the highest mortality rate in all mental illnesses.

Disorders of the brain-gut interaction (DGBI) previously known as functional gastrointestinal disorders, involve visceral hypersensitivity and motility disturbances of different parts of the gastrointestinal tract[5]. DBGI are defined by several variable combinations of chronic or recurrent gastrointestinal symptoms that do not have an identified underlying pathophysiology. In the absence of any biological marker or endoscopic modifications, the identification and classification of DGBIs is based on symptoms[6,7]. Patients suffering from DGBIs typically present with various symptoms as early satiety, postprandial fullness, bloating, nausea, emesis, and epigastric pain[6-8]. Gastrointestinal motility disorders are the result of the dysfun

Therefore, we looked for the comorbidity of DGBI and ED, in order to find out where there is an association and where there is a cause-effect relationship.

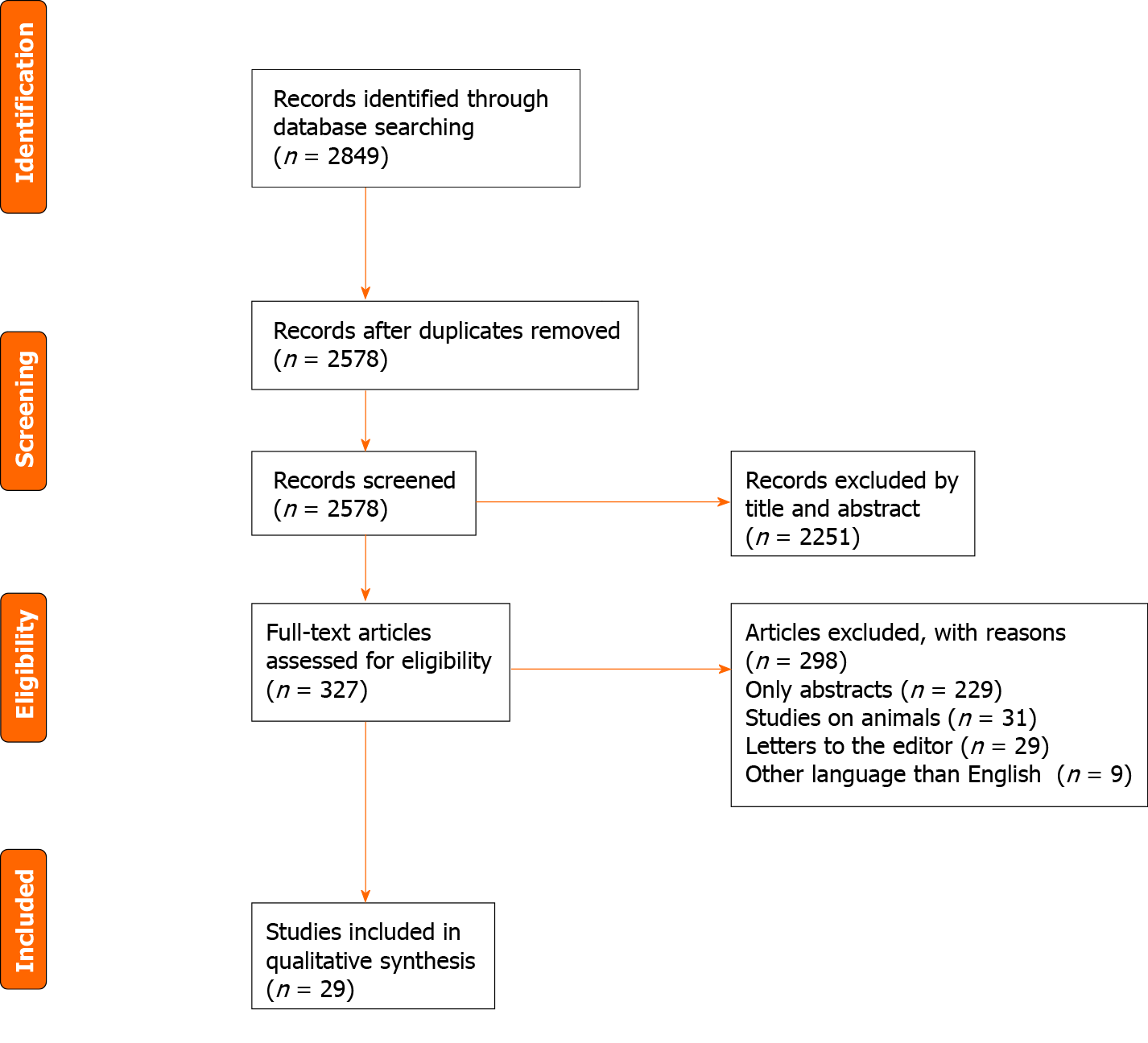

A thorough literature search was undertaken. PubMed, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, and WILEY databases were screened for relevant publications regarding DGBI in ED. The search terms included: (“Eating disorders” OR “disorders of gut-brain interaction” OR “functional gastrointestinal disorders” OR “neurogastroenterological disorders” OR “gastrointestinal motility disorders”) AND (“anorexia nervosa” OR “bulimia nervosa” OR “binge eating disorders”) AND (“gastroparesis” OR “functional dyspepsia” OR “irritable bowel syndrome” OR “functional bowel disorders”). Inclusion criteria of original articles in this systematic review were as follows: Observational cohort population-based or hospital-based and case-control studies, examining the relationship between gastrointestinal disorders and ED. Exclusion criteria were: Studies written in languages other than English, abstracts, conference presentations, letters to the editor and editorials (Figure 1). The articles included in this review refer only to DGBI present in ED. Searches were carried out by two inde

We found 29 articles analyzing the relation between DGBI and ED comprising 13 articles regarding gastroparesis (Table 1), 5 articles on functional dyspepsia (FD) (Table 2), 7 articles regarding functional constipation (FC) (Table 3) and 4 articles on irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

| Ref. | Aims | Study population | Assessment instruments | Results and conclusions |

| Szmukler et al[18], 1990 | To determine the natural history of delayed gastric emptying of solid foods in AN | 20 consecutive female inpatients. 8 restrictive AN. 10 AN and BN. 2BN. Mean age: 22.8 ± 5.2 yr. Duration of illness: 49.0 ± 37.4 mo | Scintigraphy; HET; BMI | HET > 110 min. HET significant negative correlation with BMI; delayed gastric emptying in AN improves quite rapidly as feeding recommences |

| Hutson and Wald[19], 1990 | To measure: Gastric emptying of a mixed liquid and solid meal in patients with AN, BN, and HC; the relationship of body weight and gastrointestinal symptoms to gastric emptying | 11 BN. 10 AN. A sex-matched HC | A dual radioisotope technique | Gastric emptying of solids in patients with BN was similar to that in HC (gastric T1/2 131 ± 15 min vs 119 ± 7 min; mean ± SEM). AN patients had overall delayed emptying (182 ± 31 min; P < 0.05); gastric emptying of liquids was similar in the BN and HC (gastric T1/2 48 ± 5 min and 49 ± 4 min, respectively), AN tended to have prolonged gastric emptying (65 ± 11 min, P = NS). There was no correlation between body weight, gastrointestinal symptoms, and gastric emptying |

| Benini et al[20], 2004 | To compare dyspeptic symptoms and gastric emptying times. To examine the relationship between dyspeptic symptoms, gastric motility, behavioral and psychological features of eating disorders and general psychopathology. To study the effect of simple reefeding and of long-term rehabilitation on gastric symptoms and on parameters of psychopathological distress | 23 AN. 12 binge/purging subtype. Mean age 19.9 ± 0.7 yr; mean BMI 13.2 ± 0.6, 11 restricting subtype; mean age 25.4 ± 1.1 yr; mean BMI 15.5 ± 0.7. 24 HC age and sex matched | Ultrasonographic gastric-emptying test, psychopathological questionnaires (SCL-90, EDI, EDE-Q). The bowel symptom questionnaires. VAS for hunger and epigastric fullness | Gastric symptom scores: Markedly higher in AN than in HC; improved significantly with treatment; no correlation between entry values of gastric emptying symptoms and questionnaire score was found; long-term rehabilitation improves gastrointestinal symptoms, gastric emptying and psychopathological distress in an independent manner, but not short-term refeeding |

| Inui et al[21], 1995 | Analyzing gastrointestinal motility abnormalities in ED patients | 26 female patients. 9 AN (mean age 22.5 ± 2.0 yr). 10 AN and BN (mean age 22.2 ± 1.6 yr). 7 BN (mean age 19.2 ± 1.2 yr). 9 HC | Gastric emptying: Radionuclide technique SDS; CAS | ED patients had delayed gastric emptying after ingestion of a solid meal. The patients has high depression and anxiety scores |

| Dubois et al[22], 1979 | Measure of gastric emptying and gastric output concurrently in a group of patients with AN before and after weight gain | 15 female AN age 14-32 yr; weight 34 ± 1 kg; 11 HC (8 male and 3 female) age 20-31 years old weight 68 ± 3 kg | Dye dilution technique; Barium meal x-ray examination | Fractional gastric emptying rate was significantly less in AN patients than in controls during basal conditions and following a water load, but not during maximal doses of pentagastrin. Emptying is inversely correlated with body weight in healthy controls. Gastric emptying is abnormally low in AN patients, even after weight gain |

| Kamal et al[23], 1991 | To determine whether small bowel transit time or colonic transit time is delayed in AN and BN. To determine whether delays in gastrointestinal transit are correlated with symptoms of constipation or bloating | 10 AN (9 female, 1 male). 18 BN (15 female, 3 male). 10 female HC | Whole-gut transit was tested by the radiopaque marker technique, mouth-to-cecum transit time was assessed by the lactulose breath test | Whole-gut transit time was significantly delayed in both AN (66.6 ± 29.6 h) and BN (70.2 ± 32.4 h) compared with HC (38.0 ± 19.6 h). Mouth-to-cecum transit time longer in AN (109.0 ± 33.5 min) and BN (106.2 ± 24.5 min) than in HC (84.0 ± 27.7 min), but these differences were not statistically significant |

| Robinson et al[24], 1988 | Determinants of delayed gastric emptying in AN and BN patients | 22 AN patients (21 female and 1 male). 10 BN female. 10 HC (8 female and 2 male) | Gamma camera technetium 99m-sulphur colloid | Only gastric emptying rates of the solid meal and glucose solution were significantly delayed. The gastric disturbance was confined to patients with AN patients selecting their own diet. Patients receiving adequate nutrition on the ward had normal gastric emptying and weight gain in this group had no significant effect on emptying. Slow emptying was observed in patients who maintained a low weight solely by food restriction as well as in patients whose AN was complicated by episodes of bulimia. Gastric emptying in BN was normal |

| Bluemel et al[26], 2017 | Relationship of postprandial gastrointestinal motor and sensory function with body weight | 24 AN [BMI 14.4 (11.9–16.0) kg/ | MRI and 13C-lactose-ureide breath test | Gastric half-emptying time (t50) was slower in AN than HC (P = 0.016) and OB (P = 0.007). A negative association between t50 and BMI was observed between BMI 12 and 25 kg/m2 (P = 0.0). Antral contractions and oro-cecal transit were not different. Self-reported postprandial fullness was greater in AN than in HC or OB (P < 0.001). After weight rehabilitation, t50 in AN tended to become shorter (P = 0.09) and postprandial fullness was less marked (P < 0.01) |

| Holt et al[27], 1981 | Gastric emptying of the solid and liquid components of a physiological test meal | 10 AN female patients, age 17-32 yr, mean weight 42 kg. 12 HC (6 females, 6 males, age 32-65 yr; mean weight 67 kg | Scintiscanning method | Significantly slower gastric emptying was found for both the liquid and the solid components of the meal in AN patients compared with HC. Emptying during the early phase (0-40 mm after meal ingestion) was not significantly differently in the two groups |

| Abell et al[28], 1987 | Gastrointestinal and neurohormonal function measuring gastric electrical activity, antral phasic pressure activity, gastric emptying of solids and liquids, and hormonal and autonomic function in AN patients | 8 AN (2 male and 6 female), age: 16-31 yr. 8 HC (2 male and 6 female) age19-34 yr | Gastric electrogastrography and manometry (fasting and postprandially), radioscintigraphic gastric emptying test, cold pressor test | AN patients: Increased episodes of gastric dysrhythmia (mean percentage of dysrhythmic time: 9.75 patients vs 0.48 controls during fasting, P < 0.02; 7.21 patients vs 0.18 controls postcibally, P < 0.001); impaired antral contractility (mean motility index, 12.8 patients vs 14.2 controls, P < 0.002); delayed emptying of solids; decreased postcibal blood levels of norepinephrine and neurotensin; impaired autonomic function |

| Rigaud et al[29], 1988 | Effects of renutrition on gastric emptying in AN patients | 14 AN inpatients (13 female and 1 male); duration of illness: 9 mo-40 yr; mediane 5.9 yr); age 18-61 yr | Double-isotope technique (111In) DTPA and 99mTc-ovalbumin | Gastric emptying can be improved by a renutrition program in AN |

| Waldholtz et al[30], 1990 | To determine the type and frequency of gastrointestinal symptoms. To follow symptoms during refeeding prospectively. To develop guidelines for gastrointestinal testing and intervention in hospitalized AN patients | 16 AN consecutive patients in their early 20 s, chronically ill (4.5 ± 1.2 yr); 71.6% ± 2.9% of matched population weight, 12 HC | AN patients rated on 12 gastrointestinal symptoms before and after nutritional rehabilitation. GISS (24 questions); blood tests physical examination | Belching did not improve during treatment. No patients required endoscopy, x-ray evaluation, or antipeptic regimens. Although severe gastrointestinal symptoms are common in AN, they improve significantly with refeeding |

| Murray et al[33], 2020 | To identify the frequency of FED symptoms and evaluate the relations between FED symptoms, gastrointestinal symptoms, and gastric retention | 288 patients (ages 17-78 yr; 77.5% female). Age 42.7 ± 16.3 yr; BMI 26.3 ± 6.5 (kg/m2). AN 5 (2.0%) Other Specified FED 23 (9.4%) Unspecified FED-Restrictive 24 (8.3%) | GES, NIAS, EDDS, PAGI-SYM, GCSI | FED symptoms: Were common (55%), particularly ARFID symptoms (23%-40%); Were associated with greater GI symptom severity, but not gastric retention |

| Ref. | Aims | Study population | Assessment instruments | Results and conclusions |

| Santonicola et al[37], 2012 | Prevalence of FD | 20 AN, 6 BN, 10 EDNOS, 9 CT, 32 OB, 22 HC | Rome III criteria (18 questions diagnosis of FD and its subgroups PDS and EPS) | 90% AN, 83.3% BN, 90% EDNOS, 55.6% OB and 18.2% CT met PDS criteria. Emesis was present in 100% BN patients, 20% EDNOS, 15% AN, 22% of CT subjects, 5.6% HC. Postprandial fullness intensity-frequency score was significantly higher in AN, BN, EDNOS. Nausea and epigastric pressure were increased in BN and EDNOS |

| Porcelli et al[38], 1998 | Presence of lifetime ED in patients referred for FGID | 127 consecutive patients (42 FD, 28 IBS 20 FAP, 37 with FD and IBS; male and 83 females; 163 control subjects gallstone disease | GSRS; HADS (HADS-A and HADS-D) | Past ED were significantly more prevalent in FGID (15.7%) than in gallstone disease patients (3.1%) (chi-square = 14.6, P < 0.001). FGID patients with past ED were significantly younger, more educated, more psychologically distressed, more dyspeptic, and more were women than FGID patients without past ED |

| Cremonini et al[39], 2009 | Severity of BE episodes would be associated with upper and lower GI symptoms | 4096 subjects (population-based survey of community residents found through the medical record linkage system) > 18 yr | Questionnaire measuring GI symptoms, frequency of BE episodes and physical activity level | BE disorder: Was present in 6.1% subjects, was independently associated with upper. GI symptoms: Acid regurgitation heartburn, dysphagia, bloating and upper abdominal pain, was associated with lower GI symptoms: diarrhea, urgency, constipation and feeling of anal blockage. The associations independent of the level of obesity |

| Jáuregui et al[40], 2011 | QoL in FD patients psychopathological features that underlie the FD | 245 people (mean age 28.36 ± 11.26 yr; 189 female and 56 male) 78 patients with ED (70 female and 8 male, mean age 22.88 ± 8.28 yr), 90 university students with associated FD (76 female and 14 male, mean age 22.49 ± 4.27 yr); 77 psychiatric patients (non-ED) (43 female and 34 male, mean age 40.78 ± 9.40 yr) | NDI-SF, BDI, STAI, TSF-Q, VAS | Satiation and bloating were significantly higher in ED patients. Correlations between dyspepsia and TSF were initially positive and significant in all cases, but significance was only maintained in the group of ED patients. Predictors of quality of life in ED patients: dyspepsia, depressive symptomatology, TSF-conceptual, TSF-interpretative and total TSF |

| Santonicola et al[41], 2019 | Relationship among anhedonia, BED and upper gastrointestinal symptoms in 2 group of morbidly OB with and without SG | 81 OB without SG, 45 OB with SG, 55 HC | BDI, STAI, SHAPS, ROME IV criteria for FD and its subtypes | OB without SG showed a higher prevalence of PDS, mood disorders and anxiety when positive for BE behavior compared to those negative for BE behavior, no differences were found in SHAPS score. OB with SG showed a higher prevalence of PDS compared to OB without SG. BED and depression are less frequent in the OB with SG, while state and trait anxiety are significantly higher. The more an OB with SG is anhedonic, less surgical success was achieved |

| Ref. | Aims | Study population | Assessment instruments | Results and conclusions |

| Chun et al[47], 1997 | Colorectal function measuring colonic transit and anorectal function in AN with constipation during treatment with a refeeding program | Prospective study 13 AN females; 20 age-matched, female HC | Radiopaque marker technique; anorectal manometry | Colonic transit is normal/returns to normal in the majority of AN patients once they are consuming a balanced weight gain or weight maintenance diet for at least 3 wk |

| Sileri et al[48], 2014 | Prevalence and type of defecatory disorders in AN patients | 85 patients (83 female and 2 male); mean age 28 ± 13 yr; BMI 16 ± 2 kg/m2; 57 HC, BMI 22 ± 3 kg/m2 | WCS, OD score, FISI | All results influenced by the severity of the disease (BMI; duration). The percentage of defecatory disorders rises from 75 to 100% when BMI is < 18 kg/m2 and from 60% to 75% when the duration of illness is ≥ 5 yr (P < 0.001 and P = 0.021) |

| Chiarioni et al[49], 2000 | Anorectal and colonic function in AN patients complaining of chronic constipation | 12 AN female (age 19-29 yr) chronic constipation. 12 female HC | Anorectal manometry; radiopaque technique; test of rectal sensation | AN patients: anorectal motor abnormalities (slow colonic tranzit time, pelvic floor dysfunction) |

| Boyd et al[50], 2005 | Prevalence and type of FGIDs in AN, BN and EDNOS patients; relationships between psychological features, eating-disordered attitudes and behaviours, demographic characteristics and the type and number of FGIDs | 101 consecutive female AN (n = 45, 44%), EDNOS (n = 34, 34%), BN (n = 22, 22%). Mean age 21 yr | Rome II modular questionnaire GI, ENS, BDI, STAI, BSI somatization subscale, EEE-C, version 4, EDI-2, EAT | 52% IBS (constipation-predominant 22%, diarrhoea-predominant 6%, alternating 24%), FH (51%), FAB (31%), FC (24%), FDys (23%), FAno (22%). 52% of patients exhibited 3 or more coexistent FGID diagnoses. Psychological variables (somatization, neuroticism, state and trait anxiety), age and binge eating were significant predictors of specific, and > 3 coexistent FGIDs |

| Murray et al[51], 2020 | Frequency of and relation between EDs and constipation in patients with chronic constipation referred for anorectal manometry | 279 patients with chronic constipation (79.2% female). Average age (SD) 46.6 ± 17.2 yr | EAT, PAC-SYM, HADS, VSI, ARM, colonic transit testing (24 radiopaque markers) | 19% had clinically significant ED pathology. ED pathology might contribute to constipation via gastrointestinal-specific anxiety |

| Dykes et al[52], 2001 | Past and current psychological factors associated with slow and normal transit constipation. | 28 consecutive constipated female patients, mean age 38.2 yr (SD 10.8 yr) | SCID, SF-36, EAT | 1/5 current affective disorder, 2/3 previous affective disorder, 1/3 distorted attitudes to food |

| Waldholtz et al[30], 1990 | Type and frequency of GI symptoms. To follow symptoms during refeeding prospectively. Guidelines for gastrointestinal testing and intervention in hospitalized AN patients | 16 consecutive AN patients chronically ill (4.5 ± 1.2 yr); 71.6% ± 2.9% of matched population weight, 12 HC | AN patients rated on 12 gastrointestinal symptoms before and after nutritional rehabilitation GISS (24 questions); blood tests physical examination | Belching did not improve during treatment; no patients required endoscopy, x-ray evaluation, or antipeptic regimens; although severe gastrointestinal symptoms are common in AN, they improve significantly with refeeding |

Gastroparesis is a neuromuscular disorder of the upper gastrointestinal tract characterized by delayed gastric emptying in the absence of mechanical obstruction of the stomach[15,16]. The clinical outcome of the delayed gastric emptying is a combination of symptoms, including early satiety, postprandial fullness, nausea, vomiting, belching, and bloating. The complicated overlap between upper gastrointestinal symptoms leads to a difficult diagnosis between gastroparesis and other DGBIs, such as FD, gastroparesis like syndrome and other organic gastrointestinal disorders[17]. A precise diagnosis requires measurement of gastric emptying using gastric scintigraphy, which is considered a gold standard diagnosis technique or using breath testing[15-17].

The etiology of gastroparesis is multifactorial: Diabetes mellitus, infectious, connective tissue diseases, prior gastric surgery, visceral ischemia, myopathic diseases, neurological diseases (most frequent Parkinson disease), coma or artificial ventilation and medications (especially opiate narcotic analgesics and anticholinergic agents)[17]. Nevertheless, the etiology cannot be established in more than 50% cases, representing idiopathic gastroparesis. The pathogenesis of gastroparesis is also complex, and abnormalities in fundic tone, gastroduodenal dyscoordination, a weak antral pump, gastric dysrhythmias, abnormal duodenal feedback justify the reason why gastroparesis is considered a part of a broader spectrum of gastric neuromuscular dysfun

A study performed by Hutson et al[19] analyzed gastric emptying of a mixed liquid and solid meal in 11 patients with bulimia nervosa and was compared with ten patients with anorexia nervosa and a sex-matched control population[19]. The authors of the study decided to use a dual radioisotope technique in order to measure gastric emptying. Similar to previous studies, the relationship between body mass index and gastrointestinal symptoms were also examined. Authors reported at gastric emptying of solids in patients with bulimia nervosa was similar to that in controls (gastric T1/2 131 ± 15 min vs 119 ± min; mean ± SEM) and anorexia nervosa patients had overall significantly delayed emptying (182 ± 31 min[19]. Gastric emptying of liquids was similar in bulimic patients and healthy controls[19]. The study did not find any correlation between body mass index, gastrointestinal symptoms, and gastric emptying, indicating that gastrointestinal symptoms are unreliable criteria of gastric emptying in patients with ED[19]. Although gastric scintigraphy is the gold standard technique for measuring gastric emptying, not all studies use it. A study performed by Benini et al[20] analyzed 23 anorexic patients using an ultrasonographic gastric-emptying test and psychopathological questionnaires, before and after 4 and 22 wk rehabilitation[20]. The result was that gastric symptom scores were markedly higher in patients than in controls and improved significantly with treatment. Further, no correlation between entry values of gastric emptying symptoms and questionnaire score was found[20]. The study summarized that long-term rehabilitation improves gastrointestinal symptoms, gastric emptying, and psychopathological distress, and short-term does not.

A study performed by Inui et al[21] analyzed gastrointestinal motility abnormalities in 26 female patients who met the DSM-III-R criteria for ED[21]. Gastric emptying was measured using a radionuclide technique, and all patients were additionally evaluated using a self-rating depression scale and the Cattell anxiety scale. Nine patients were diagnosed with anorexia nervosa, 10 with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, and 7 with bulimia nervosa. In addition, the time expressed in minutes at which half the meal was emptied from the stomach was measured. Patients with anorexia nervosa, anorexia nervosa with bulimia nervosa, and bulimia nervosa all had delayed gastric emptying as compared to nine normal healthy controls and had delayed gastric emptying after ingestion of a solid meal, regardless of DSM-III-R classification[21]. The authors concluded that impaired gastric motility might be caused not only by food restriction or emesis but also by other independent factors from the patient nutritional state[21].

The intricate effect of depression and anxiety shows that gastroparesis pathogenesis is more complex, and psychotherapy may have an essential role in the nutritional rehabilitation of patients with ED. Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa were the most frequent ED associated with gastroparesis, a fact demonstrated by numerous studies over the last 6 decades[22-30]. Limited evidence regarding the association of gastroparesis and pica, night eating disorder and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder was found[22-30].

FD is one of the most frequent DGBIs and is defined using the Rome IV criteria as any combination of the following symptoms: Postprandial fullness, early satiety, epigastric pain, and epigastric burning that are severe enough to interfere with the usual activities and occur at least three days per week over the past three months with an onset of at least six months before presentation[31].

FD includes three syndromes: (1) Postprandial distress syndrome; (2) Epigastric pain syndrome; and (3) Overlapping postprandial distress syndrome and epigastric pain syndrome[31-33]. The pathophogensis of FD is multifactorial and incompletely understood. Dysfunctional gastrointestinal motility (antral hypomotility, delayed or rapid gastric emptying, impaired gastric accommodation), psychological stress, visceral hypersensitivity, psychiatric disorders (depressive disorder, anxiety disorder), gastric or duodenal hypersensitivity to specific types of food and gastric distension, have been incriminated as pathogenesis mechanisms[34-44]. Smokers, women, patients with Helicobacter pylori infection, ED patients, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug users have an increased risk of developing FD[34-44].

The dyspeptic symptoms may be encountered in ED. Thus, a study performed by Santonicola et al[37] analyzed the prevalence of FD in ED patients, constitutional thinner subjects with no pathology, obese patients, and healthy volunteers[37]. The patients were recruited from a clinic specialized in treating ED, and the study groups included 20 anorexia nervosa patients, six bulimia nervosa patients, ten unspecified eating disorder patients, nine constitutional thinner subjects, 32 obese patients and 22 healthy controls[37]. The presence of epigastric pain syndrome and postprandial distress syndrome were diagnosed according to Rome III criteria. The intensity and frequency score of early satiety, epigastric fullness, epigastric pain, epigastric burning, epigastric pressure, belching, nausea, and vomiting were measured by a standardized questionnaire[37]. The result was that 90% of anorexia nervosa patients, 83.3% of bulimia nervosa patients, 90% of unspecified eating disorder patients, 55.6% of constitutionally thin subjects and 18.2% of the healthy volunteers met the postprandial distress syndrome criteria (χ2, P < 0.001) and only one bulimia nervosa patient met the epigastric pain syndrome criteria[37]. Emesis was present in 100% of bulimia nervosa patients, in 20% of ED not otherwise specified patients, in 15% of anorexia nervosa patients, in 22% of constitutional thinner subjects, and, in 5.6% healthy volunteers (χ2, P < 0.001)[37]. The pathologic eating behavior causes dysfunctional gastrointestinal sensitivity and motility, and after a variable period of time, the resulting DGBIs can persist independently of the eating disorder that originally caused the motility dysfunction[38].

A study performed by Cremonini et al[39] analyzed the gastrointestinal symptoms associated with binge ED[39]. A population-based survey of community residents through a mailed questionnaire was performed, and a total of 4096 subjects were included in the study. Binge eating disorder was present in 6.1% of subjects and was associated with the following gastrointestinal symptoms: Acid regurgitation, heartburn, dysphagia, bloating and epigastric pain, diarrhea, constipation and feeling the sensation of anal blockage[39]. The study demonstrated that both upper and lower gastrointestinal symptoms appear in binge ED.

Although the number of studies analyzing ED and FD is small, dyspeptic symptoms are more common in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa patients.

A limitation of most studies regarding FD in ED is that a clear delimitation between meal-related gastrointestinal symptoms is lacking, and future studies analyzing the theoretical and clinical implications might help in developing a more efficient diagnosis and therapeutic scheme[40,41].

FC is defined according to the Rome IV criteria as a change in bowel habit, or defecatory behavior that results in acute or chronic symptoms or diseases that would be resolved with the relief of constipation and a patient must have experienced at least two of the symptoms over the preceding three months[45,46]. FC is present also in ED. Thus, a study by Chun et al[47] analyzed the prevalence of FC in anorexic patients by measuring colonic transit and anorectal function[47]. The first study group consisted of 13 anorexic females, and the second study group consisted of 20 healthy female control subjects. Colonic transit was measured using a radiopaque marker technique, and anal sphincter function, rectal sensation, expulsion dynamics, and rectal compliance were measured with anorectal manometry[47]. The result showed that colonic transit returns to normal in the majority of patients after they start to finish a specialized refeeding program[47].

A study performed by Sileri et al[48] analyzed the prevalence of defecatory disorders in anorexic patients[48]. The Wexner constipation score (WCS), Altomare's obstructed defecation score (ODS), and the fecal incontinence severity index were used to evaluate constipation and incontinence of 83 female anorexic patients and 57 healthy volunteers. The result showed that constipation (defined as WCS ≥ 5) was present in 83% of anorexic patients and in 12% of healthy controls (P = 0.001), while obstructed defecation syndrome (defined as ODS ≥ 10) was present in 84% of anorexic patients and in 12% of healthy controls (P < 0.001)[48].

A study performed by Chiarioni et al[49] evaluated the prevalence and pathogenetic mechanisms of FC in 12 female anorexic patients and 12 healthy female controls[49]. Pelvic floor dysfunction was analyzed using an anorectal manometry, and colonic transit time was measured by a radiopaque marker technique.

A subgroup of 8 patients was retested after a specialized refeeding program[49]. The results showed that 66.7% of anorexic patients had slow colonic transit times, and 41.7% had pelvic floor dysfunction. The specialized refeeding program normalized the colonic transit time in the subgroup of 8 patients, but pelvic floor dysfunction did not normalize in these patients[49]. The study demonstrated that anorectal motility dysfunctions and delayed colonic transit are frequent in anorexic patients, a result also shown by other studies[30,50-52].

Although, the relation between FC and ET was analyzed in a limited number of studies, a significant association between the disorders was found.

IBS is one of the most frequent DGBIs characterized by abdominal pain and altered bowel habit in the absence of a specific organic pathology[53,54]. Epidemiologic studies show that the prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome is 10%-20% and the incidence of 1%-2% per year[53,54]. Perkins et al[55] performed a study about the prevalence of IBS in a large sample of ED patients analyzing the timing of onset of the ED symptomatology and assessing if they are predictors of IBS. The result of the study was that 64% of ED patients met the Manning criteria for IBS and 87% had developed their ED before the onset of IBS symptoms, with a mean period of time of 10 years between the onset of ED and IBS demonstrating that EDs increase the risk of IBS[55].

A study performed by Dejong et al[56] examined the prevalence of IBS in patients with bulimia nervosa and showed a high prevalence of IBS in the bulimia nervosa group (68.8%) [b]. IBS diagnosis was assessed using the Manning criteria and even if the study demonstrated a high incidence of IBS in patients with BN, the relationship between those disorders remain unclear[56]. A study performed by Sullivan et al[57] on 48 IBS patients, 32 ED patients, 31 inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients and 28 healthy controls analyzed the relationship between IBS, IBD and ED. The results showed that the eating Attitudes Test score for the IBS group was higher than IBD and control group (P = 0.05), demonstrating the correlation between IBS and ED[57].

The relation between clinical characteristics of ED and IBS was investigated in a study performed by Tang et al[58] on 60 IBS patients. The result was that the severity of IBS symptomatology was correlated with Perfectionism and Ineffectiveness and severe episodes of emesis were associated with self-reported binge-purge behaviors measured by the Bulimia subscale of the EDI[58]. Bulimia nervosa was more common in IBS patients, but no data about the effect of psychiatric therapy on IBS symptoms was found.

In this review we looked for current evidence of the association of neurogastroenterological disorders with ED. We identified 29 studies, focusing on four gastrointestinal disorders associated with ED (gastroparesis, FD, FC and irritable bowel syndrome). Despite progress in the field of neurogastroenterology, we were not able yet to identify a causative relation between neurogastroenterological disorders and ED.

One of the strengths of this study is that it highlights the overlap between ED and neurogastroenterological disorders, a fact of paramount importance for the management of those patients who often are affected with both type of disorders, but, just as often, are treated for only one disorder, depending on whether they visit the psychiatrist or the gastroenterologist.

No relation between gastroesophageal reflux disease and ED was found[11-14]. A limited number of studies investigated the rumination syndrome but we were not able to find supportive data about the association between rumination and ED.

The small number of patients included in the majority of studies represent the main limitation and future studies under the support of international collaboration might help in developing a more efficient therapy. Another limit of most studies regarding FD is that a clear delimitation between meal-related gastrointestinal symptoms is lacking, and future studies using an animal model might help in developing precise diagnosis tools[40-44]. Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa were the most frequent ED associated with FD[37-39]. Most studies about FC showed that anorectal motility dysfunctions and delayed colonic transit are frequent in anorexic patients and anorexia nervosa was the most frequent eating disorder associated with FC[47-53]. IBS was associated with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa[55-58].

Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa were the most frequent ED associated with gastroparesis[18-21]. A major limit in studies concerning gastroparesis was the fact that not all studies use gastric scintigraphy for diagnosis, although it is the gold standard technique for measuring gastric emptying. Thereby, a lack of a clear distinction between gastroparesis and FD was present[20,21,59].

Clear evidence for a cause effect relationship between ED and DGBI, still does not exist. More powerful studies are required. In respect to therapy of DGBI in ED, the absence of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) is the main reason why no guidelines for gastrointestinal symptomatology in ED exist. These limitations can be overcome by projecting larger RCTs with significant samples of ED and DGBI patients.

There is no evidence for a cause-effect relationship between DGBI and ED. Their common symptomatology required correct identification and a tailored therapy of each disorder.

Eating disorders (ED) involve both the nervous system and the gastrointestinal tract. A similar double involvement is also found in disorders of the brain-gut interaction (DGBI) and symptoms are sometimes similar.

We aimed to understand the management of patients who often are affected with both DGBI and ED, but, just as often, are treated for only one disorder, depending on whether they visit the psychiatrist or the gastroenterologist.

This systematic review aimed to evaluate the comorbidity of DGBI and ED, in order to find out where there is an association and a cause-effect relationship.

A thorough literature search was undertaken. PubMed, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, and WILEY databases were screened for relevant publications regarding DGBI in ED.

We found 29 articles analyzing the relation between DGBI and ED comprising 13 articles on gastroparesis, 85 articles on functional dyspepsia, 7 articles about functional constipation and 4 articles on irritable bowel syndrome.

There is no evidence for a cause-effect relationship between DGBI and ED. Their common symptomatology requires correct identification and a tailored therapy of each disorder.

The absence of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) is the main reason why no guidelines for gastrointestinal symptomatology in ED exist. These limitations can be overcome by projecting larger RCTs with significant samples of ED and DGBI patients.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ukleja A S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Hay P. Current approach to eating disorders: a clinical update. Intern Med J. 2020;50:24-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rantala MJ, Luoto S, Krama T, Krams I. Eating Disorders: An Evolutionary Psychoneuroimmunological Approach. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Smink FR, van Hoeken D, Hoek HW. Epidemiology, course, and outcome of eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26:543-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in RCA: 303] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Smink FR, van Hoeken D, Hoek HW. Epidemiology of eating disorders: incidence, prevalence and mortality rates. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14:406-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1058] [Cited by in RCA: 1092] [Article Influence: 84.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Drossman DA. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: History, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology. 2016;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1366] [Cited by in RCA: 1383] [Article Influence: 153.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Abraham S, Kellow JE. Do the digestive tract symptoms in eating disorder patients represent functional gastrointestinal disorders? BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Corazziari E. Definition and epidemiology of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;18:613-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Schmulson M. How to use Rome IV criteria in the evaluation of esophageal disorders. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2018;34:258-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Levinthal DJ, Strick PL. Multiple areas of the cerebral cortex influence the stomach. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:13078-13083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Browning KN, Travagli RA. Central nervous system control of gastrointestinal motility and secretion and modulation of gastrointestinal functions. Compr Physiol. 2014;4:1339-1368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 368] [Article Influence: 36.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Person H, Keefer L. Psychological comorbidity in gastrointestinal diseases: Update on the brain-gut-microbiome axis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;107:110209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Allen AP, Dinan TG, Clarke G, Cryan JF. A psychology of the human brain-gut-microbiome axis. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2017;11:e12309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Midenfjord I, Borg A, Törnblom H, Simrén M. Cumulative Effect of Psychological Alterations on Gastrointestinal Symptom Severity in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lee SY, Ryu HS, Choi SC, Jang SH. A Study of Psychological Factors Associated with Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders and Use of Health Care. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2020;18:580-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kim BJ, Kuo B. Gastroparesis and Functional Dyspepsia: A Blurring Distinction of Pathophysiology and Treatment. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;25:27-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Stein B, Everhart KK, Lacy BE. Gastroparesis: A Review of Current Diagnosis and Treatment Options. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49:550-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Camilleri M, Chedid V, Ford AC, Haruma K, Horowitz M, Jones KL, Low PA, Park SY, Parkman HP, Stanghellini V. Gastroparesis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 287] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 34.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Szmukler GI, Young GP, Lichtenstein M, Andrews JT. A serial study of gastric emptying in anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Aust N Z J Med. 1990;20:220-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hutson WR, Wald A. Gastric emptying in patients with bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:41-46. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Benini L, Todesco T, Dalle Grave R, Deiorio F, Salandini L, Vantini I. Gastric emptying in patients with restricting and binge/purging subtypes of anorexia nervosa. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1448-1454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Inui A, Okano H, Miyamoto M, Aoyama N, Uemoto M, Baba S, Kasuga M. Delayed gastric emptying in bulimic patients. Lancet. 1995;346:1240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Dubois A, Gross HA, Ebert MH, Castell DO. Altered gastric emptying and secretion in primary anorexia nervosa. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:319-323. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Kamal N, Chami T, Andersen A, Rosell FA, Schuster MM, Whitehead WE. Delayed gastrointestinal transit times in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:1320-1324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Robinson PH, Clarke M, Barrett J. Determinants of delayed gastric emptying in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Gut. 1988;29:458-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Stacher G. Gut function in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:573-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bluemel S, Menne D, Milos G, Goetze O, Fried M, Schwizer W, Fox M, Steingoetter A. Relationship of body weight with gastrointestinal motor and sensory function: studies in anorexia nervosa and obesity. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Holt S, Ford MJ, Grant S, Heading RC. Abnormal gastric emptying in primary anorexia nervosa. Br J Psychiatry. 1981;139:550-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Abell TL, Malagelada JR, Lucas AR, Brown ML, Camilleri M, Go VL, Azpiroz F, Callaway CW, Kao PC, Zinsmeister AR. Gastric electromechanical and neurohormonal function in anorexia nervosa. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:958-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Rigaud D, Bedig G, Merrouche M, Vulpillat M, Bonfils S, Apfelbaum M. Delayed gastric emptying in anorexia nervosa is improved by completion of a renutrition program. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:919-925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Waldholtz BD, Andersen AE. Gastrointestinal symptoms in anorexia nervosa. A prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:1415-1419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Grundy D, Al-Chaer ED, Aziz Q, Collins SM, Ke M, Taché Y, Wood JD. Fundamentals of neurogastroenterology: basic science. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1391-1411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Talley NJ. Functional dyspepsia: new insights into pathogenesis and therapy. Korean J Intern Med. 2016;31:444-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Burton Murray H, Jehangir A, Silvernale CJ, Kuo B, Parkman HP. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder symptoms are frequent in patients presenting for symptoms of gastroparesis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32:e13931. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Popa SL, Chiarioni G, David L, Dumitrascu DL. The Efficacy of Hypnotherapy in the Treatment of Functional Dyspepsia. Am J Ther. 2019;26:e704-e713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Talley NJ, Hunt RH. What role does Helicobacter pylori play in dyspepsia and nonulcer dyspepsia? Gastroenterology. 1997;113:S67-S77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Karamanolis G, Caenepeel P, Arts J, Tack J. Association of the predominant symptom with clinical characteristics and pathophysiological mechanisms in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:296-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Santonicola A, Siniscalchi M, Capone P, Gallotta S, Ciacci C, Iovino P. Prevalence of functional dyspepsia and its subgroups in patients with eating disorders. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4379-4385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Porcelli P, Leandro G, De Carne M. Functional gastrointestinal disorders and eating disorders. Relevance of the association in clinical management. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:577-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Cremonini F, Camilleri M, Clark MM, Beebe TJ, Locke GR, Zinsmeister AR, Herrick LM, Talley NJ. Associations among binge eating behavior patterns and gastrointestinal symptoms: a population-based study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2009;33:342-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Jáuregui Lobera I, Santed MA, Bolaños Ríos P. Impact of functional dyspepsia on quality of life in eating disorder patients: the role of thought-shape fusion. Nutr Hosp. 2011;26:1363-1371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Santonicola A, Gagliardi M, Guarino MPL, Siniscalchi M, Ciacci C, Iovino P. Eating Disorders and Gastrointestinal Diseases. Nutrients. 2019;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Zipfel S, Sammet I, Rapps N, Herzog W, Herpertz S, Martens U. Gastrointestinal disturbances in eating disorders: clinical and neurobiological aspects. Auton Neurosci. 2006;129:99-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 43. | Robinson PH. The gastrointestinal tract in eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2000;8:88-97. |

| 44. | Robinson PH. Gastric function in eating disorders. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1989;575:456-64; discussion 464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Drossman DA, Hasler WL. Rome IV-Functional GI Disorders: Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1257-1261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 731] [Cited by in RCA: 1033] [Article Influence: 114.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Simren M, Palsson OS, Whitehead WE. Update on Rome IV Criteria for Colorectal Disorders: Implications for Clinical Practice. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2017;19:15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Chun AB, Sokol MS, Kaye WH, Hutson WR, Wald A. Colonic and anorectal function in constipated patients with anorexia nervosa. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1879-1883. [PubMed] |

| 48. | Sileri P, Franceschilli L, De Lorenzo A, Mezzani B, Todisco P, Giorgi F, Gaspari AL, Jacoangeli F. Defecatory disorders in anorexia nervosa: a clinical study. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18:439-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Chiarioni G, Bassotti G, Monsignori A, Menegotti M, Salandini L, Di Matteo G, Vantini I, Whitehead WE. Anorectal dysfunction in constipated women with anorexia nervosa. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:1015-1019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Boyd C, Abraham S, Kellow J. Psychological features are important predictors of functional gastrointestinal disorders in patients with eating disorders. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:929-935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Murray HB, Flanagan R, Banashefski B, Silvernale CJ, Kuo B, Staller K. Frequency of Eating Disorder Pathology Among Patients With Chronic Constipation and Contribution of Gastrointestinal-Specific Anxiety. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:2471-2478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Dykes S, Smilgin-Humphreys S, Bass C. Chronic idiopathic constipation: a psychological enquiry. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:39-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Saha L. Irritable bowel syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, and evidence-based medicine. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:6759-6773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 318] [Cited by in RCA: 295] [Article Influence: 26.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (14)] |

| 54. | Popa SL, Leucuta DC, Dumitrascu DL. Pressure management as an occupational stress risk factor in irritable bowel syndrome: A cross-sectional study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e13562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Perkins SJ, Keville S, Schmidt U, Chalder T. Eating disorders and irritable bowel syndrome: is there a link? J Psychosom Res. 2005;59:57-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Dejong H, Perkins S, Grover M, Schmidt U. The prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in outpatients with bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2011;44:661-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Sullivan G, Blewett AE, Jenkins PL, Allison MC. Eating attitudes and the irritable bowel syndrome. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1997;19:62-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Tang TN, Toner BB, Stuckless N, Dion KL, Kaplan AS, Ali A. Features of eating disorders in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 1998;45:171-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Usai-Satta P, Bellini M, Morelli O, Geri F, Lai M, Bassotti G. Gastroparesis: New insights into an old disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:2333-2348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |