Published online Oct 21, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i39.5926

Peer-review started: April 28, 2019

First decision: July 22, 2019

Revised: August 16, 2019

Accepted: September 13, 2019

Article in press: September 13, 2019

Published online: October 21, 2019

Processing time: 176 Days and 14.8 Hours

Proton pump inhibitors are often used to prevent gastro-intestinal lesions induced by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. However, they are not always effective against both gastric and duodenal lesions and their use is not devoid of side effects.

To explore the mechanisms mediating the clinical efficacy of STW 5 in gastro-duodenal lesions induced by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), exemplified here by diclofenac, in a comparison to omeprazole.

Gastro-duodenal lesions were induced in rats by oral administration of diclofenac (5 mg/kg) for 6 successive days. One group was given concurrently STW 5 (5 mL/kg) while another was given omeprazole (20 mg/kg). A day later, animals were sacrificed, stomach and duodenum excised and divided into 2 segments: One for histological examination and one for measuring inflammatory mediators (tumor necrosis factor α, interleukins-1β and 10), oxidative stress enzyme (heme oxygenase-1) and apoptosis regulator (B-cell lymphoma 2).

Diclofenac caused overt histological damage in both tissues, associated with parallel changes in all parameters measured. STW 5 and omeprazole effectively prevented these changes, but STW 5 superseded omeprazole in protecting against histological damage, particularly in the duodenum.

The findings support the therapeutic usefulness of STW 5 and its superiority over omeprazole as adjuvant therapy to NSAIDs to protect against their possible gastro-duodenal side effects.

Core tip: The herbal preparation STW 5, clinically used in functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome, was compared to omeprazole in protecting against diclofenac- induced gastro-duodenal lesions in rats. Both drugs were effective in preventing changes in the level of inflammatory mediators (tumor necrosis factor α, interleukins-1β and 10), in the level of the oxidative stress enzyme, heme oxygenase-1, and the apoptotic regulator (B-cell lymphoma 2) in both stomach and duodenum. However, STW 5 was more effective than omeprazole in protecting against the histological damage. The results emphasize the potential usefulness of STW 5 and its superiority over omeprazole in protecting against gastro-duodenal lesions induced by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

- Citation: Khayyal MT, Wadie W, Abd El-Haleim EA, Ahmed KA, Kelber O, Ammar RM, Abdel-Aziz H. STW 5 is effective against nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs induced gastro-duodenal lesions in rats. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(39): 5926-5935

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i39/5926.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i39.5926

The long-term use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as diclofenac, has been reported to cause various adverse effects on the gastro-intestinal tract, including lesions in the stomach and duodenum, irritation of the mucosal surface and dyspepsia[1]. Various mechanisms have been involved in the development of these side effects, such as local epithelial irritation, inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis, and interference with barrier function and mucosal blood flow[2]. While proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) have been advocated to protect against the injurious effect of NSAIDs, some authors failed to show that omeprazole was capable of healing mucosal lesions caused by diclofenac[3]. Because of the fact that PPIs and other agents like H2 receptor blockers are not devoid of side effects on their own, attention has been shifted to the use of relatively safe and better tolerated herbal preparations.

A recent review article[4] emphasizes the use of natural products and herbal medicines to counteract the undesirable side effects of NSAIDs. One of the herbal preparations with established clinical efficacy in gastro-intestinal disorders such as functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome[5] as well as in drug-induced gastro-intestinal disturbances[6] is STW 5. It was shown to have a favorable safety profile[7] and has recently been included in the Rome IV treatment algorithm as a treatment option for functional dyspepsia[8].

The anti-inflammatory and mucosal protective properties of STW 5 were investigated and documented in several animal models of gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, including reflux esophagitis[9], gastric ulcer[10] and ulcerative colitis[11]. The present study aims at shedding more light on mechanisms mediating the clinical efficacy of STW 5 in gastro-duodenal lesions induced by NSAIDs[6], exemplified here by diclofenac, using an experimental model.

Adult female Wistar rats, each weighing 150-200, were purchased from the National Research Centre, Giza, Egypt. They were housed in Perspex cages, housing 5 animals per cage, at the Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University, at a temperature of 25 ± 2 °C and a relative humidity of 60%-70%, and a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle. Taking in consideration that the diet might influence the outcome of some pharmacological experiments[12], it should be emphasized that the animals were fed a normal chow diet consisting of 66% carbohydrates, 22% protein, 6% fats, 3% fiber and 3% minerals and vitamins mixture and purchased from Alfa Media Trade (Giza, Egypt) and allowed water ad libitum. This diet was previously used in earlier experiments with STW 5 with no influence on the outcome of the results[11]. They were allowed to acclimatize for 1 wk before being subjected to experimentation. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee for experimentation with laboratory animals (Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University) following the revised guidelines of the European Economic Community regulations (86/609/EEC) (Permit Number: PT 2292).

Diclofenac was obtained from Novartis Pharma, Egypt; Omeprazole from Eipico, Egypt; STW 5 (Iberogast®) was generously supplied by Steigerwald Arzneimittelwerk GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany. STW 5 consists of a combination of standardized fixed proportions of hydro-alcoholic extracts of the following medicinal herbs Iberis amara, Melissa officinalis, Matricaria recutita, Carum carvi, Mentha piperita, Angelica archangelica, Silybum marianum, Chelidonium majus and Glycyrrhiza glabra. The other chemicals used were all of analytical grade.

Four groups of animals, consisting of 10 rats each, were randomly allocated as follows:

Group 1: Normal untreated control rats; Group 2: Rats treated with diclofenac orally in a daily dose of 5 mg/kg for 6 d; Group 3: Rats treated orally with diclofenac (5 mg/kg) together with omeprazole (20 mg/kg) daily for 6 d. The dose of omeprazole was formerly reported to be effective for this purpose[13]; Group 4: Rats treated orally with diclofenac (5 mg/kg) together with STW 5 (5 mL/kg) daily for 6 d.

The dose of diclofenac and length of period of administration were chosen on the basis of preliminary experiments carried out in our lab to determine an appropriate dose of diclofenac to be given for a suitable number of days in order to induce reproducible gastro-duodenal lesions without causing appreciable animal mortalities under our experimental conditions. Accordingly, treatment in the above groups was given for 6 d. This is in agreement with an earlier study which reported that diclofenac was used in a dose of 5 mg/kg for 7 d in rat for evaluation of its gastric tolerability[14]. Furthermore, the dose of STW 5 was based on earlier studies in our lab showing good anti-inflammatory activity and good tolerability in experimental animals[15].

The animals were sacrificed by decapitation under light ether anesthesia on the seventh day and the stomach and duodenum were isolated and divided into 2 segments. One segment was preserved in 10% formalin for histological examination, while the other was homogenized in ice-cold normal saline to obtain a 10% homogenate that was stored at -20 ºC for the assay of different relevant parameters at a later stage. These comprised the cytokines involved in inflammation, namely, interleukin 1β (IL-1β), IL-10, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) as well as the enzyme, heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), as a measure of oxidative stress and B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl2) as an indicator of apoptosis. These parameters were determined using rat specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (R and D Systems GmbH, Wiesbaden, Germany) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

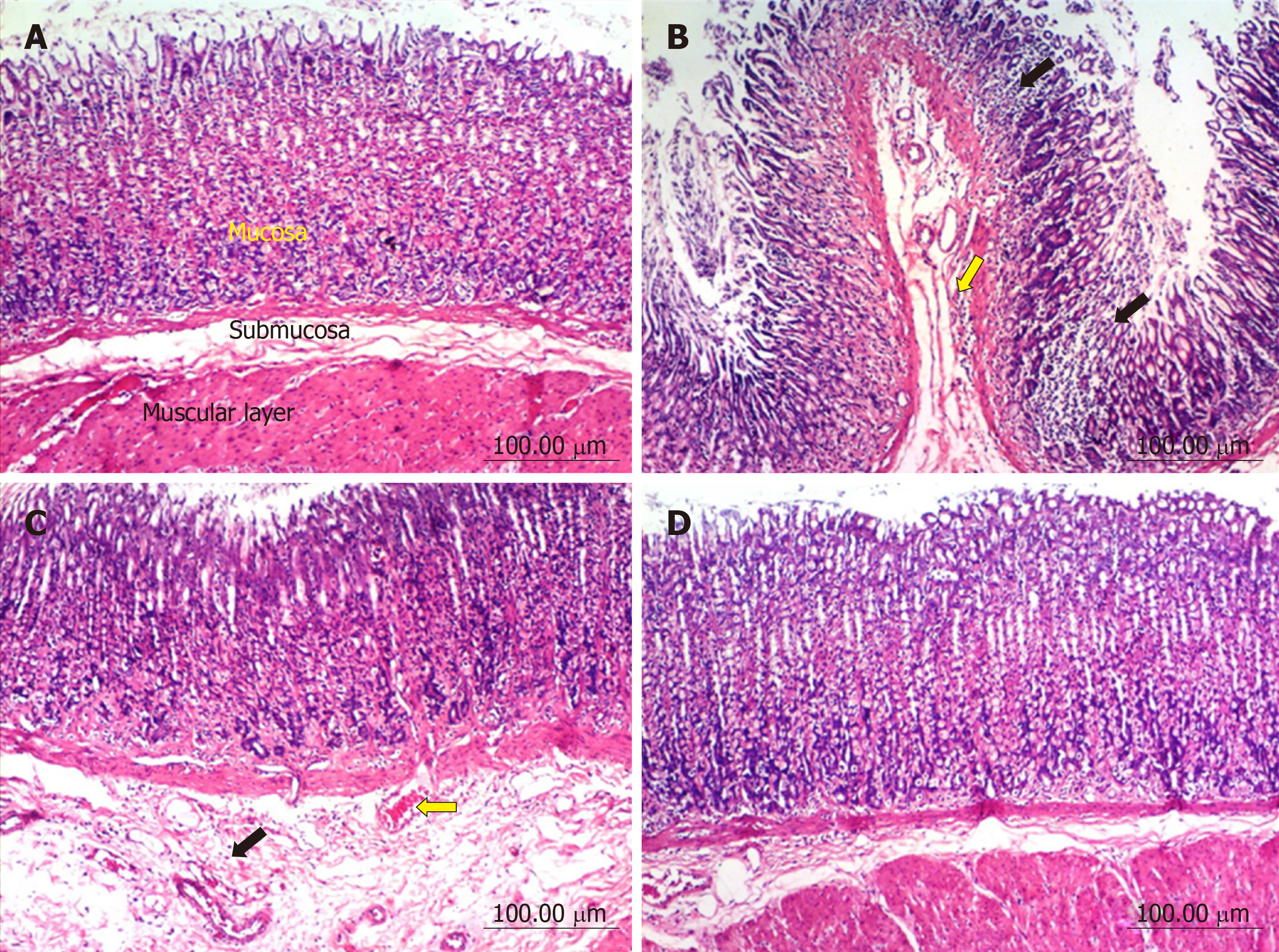

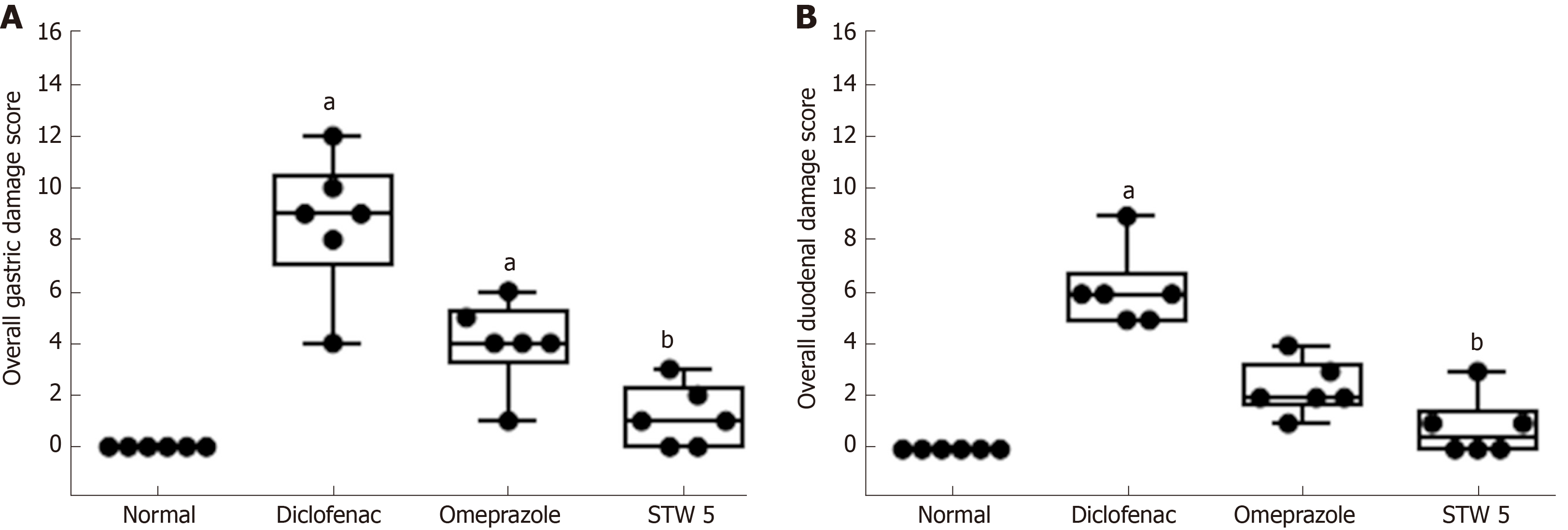

The fixed stomach and duodenum segments were processed by paraffin embedded technique and transverse 4-5 µm sections were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin for light microscopic examination. The histological damage in the gastric sections was assessed by examining them for 5 criteria representing cell damage, namely: (1) Focal mucosal necrosis; (2) Congestion of the sub-mucosal blood vessels; (3) Sub-mucosal edema; (4 and 5) Inflammatory cell infiltration in the mucosa and sub-mucosa. The extent of damage for each of these signs was assessed on a score from 0 (normal) to 3 (severe). An overall damage score (ODS) was then computed semi-quantitatively for each examined slide[16].

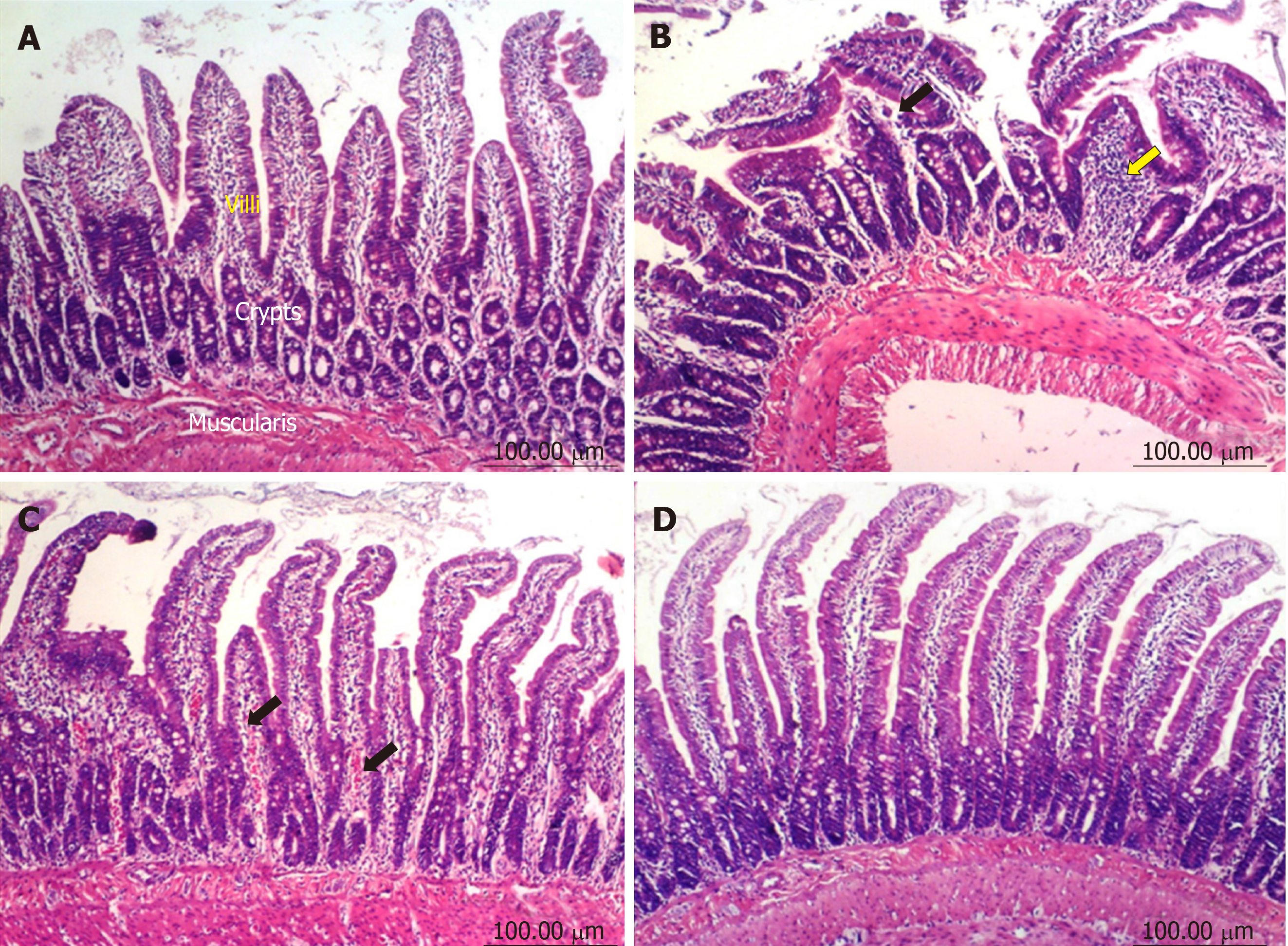

For the duodenal sections, six criteria were studied, namely, focal necrosis of the mucosa, infiltration of inflammatory cells in the lamina propria, mucosal edema, congestion of blood vessels, activation of glands and sub-mucosal edema. Accordingly, a maximal ODS for gastric and duodenal sections was computed to be 15 and 18, respectively. The data was then represented as a box plot.

The histological scores were represented as a box plot using the medians analyzed by Kuskal-Wallis followed by Dunn’s test. The other data were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD) and analyzed by one-way-analysis of variance test (ANOVA) followed by Tukey Kramer multiple comparisons test, setting the level of significance at P ≤ 0.05.

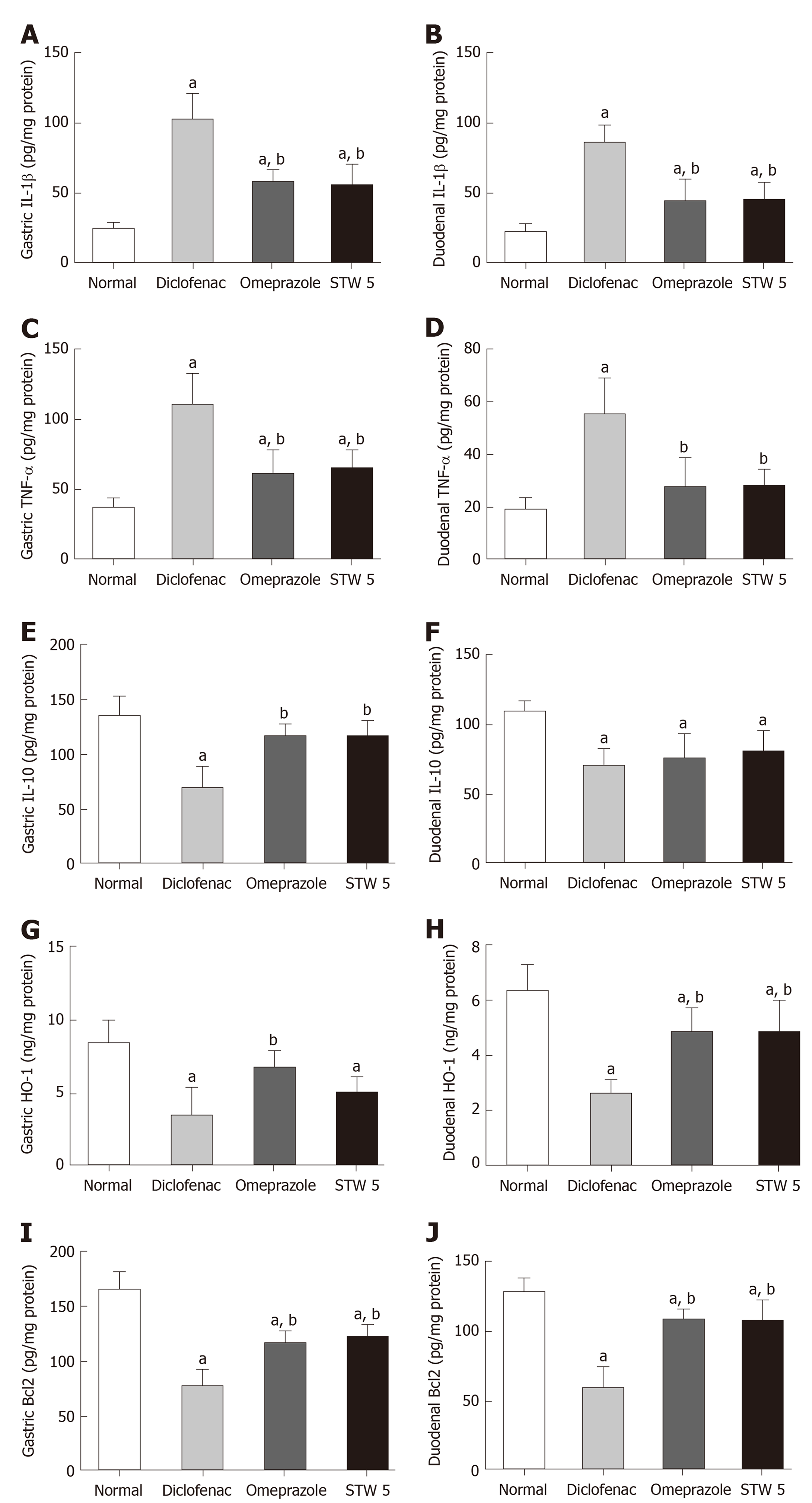

Diclofenac administration showed a marked 4-fold increase in the level of the pro-inflammatory cytokine, IL-1β, in both stomach and duodenum as compared to untreated control. Treatment with omeprazole and STW 5 tended to protect against this increase nearly to the same extent, such that the increase of the cytokine was reduced only to about two-fold (Figure 1A and B). The other pro-inflammatory cytokine, TNF-α, was also markedly increased after diclofenac administration, albeit not as much as IL-1β. Both omeprazole and STW 5 in the doses used tended to prevent this increase in both tissues (Figure 1C and D). In parallel with these findings, the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10, was significantly reduced by diclofenac in both stomach and duodenum, an effect that was largely prevented by both omeprazole and STW 5 mainly in the stomach, albeit to a non-statistically significant extent in the duodenum (Figure 1E and F).

With respect to HO-1, an anti-oxidant as well as anti-inflammatory enzyme, diclofenac was shown to induce a marked drop in its gastric and duodenal level. Omeprazole was effective in preventing the changes in both tissues, whereas STW 5 was effective only in ameliorating the diclofenac-induced reduction in the duodenum (Figure 1G and H). The levels of the apoptotic regulator, Bcl2 were suppressed by more than half by diclofenac in both the stomach and duodenum, an effect which tended to be prevented by treatment with either omeprazole or STW 5 almost to the same extent. (Figure 1I and J).

Stomach: The stomach of control untreated rats showed a normal histological structure of gastric mucosa, submucosa and muscularis layers (Figure 2A). On the other hand, stomach of rats treated with diclofenac showed severe histopathological alterations evidenced as multiple focal necrosis of gastric mucosa associated with mononuclear cells infiltration as well as submucosal edema and inflammatory cell infiltration (Figure 2B). Some sections also showed cystic dilatation of the gastric glands. However, the stomach of rats treated with diclofenac/omeprazole showed only mild submucosal edema associated with mononuclear cell infiltration and congested submucosal blood vessel (Figure 2C). A further improvement of the picture was shown in the stomachs of rats treated with diclofenac/STW 5, where only a few sections showed mild submucosal edema with some inflammatory cell infiltration and congested submucosal blood vessels, but most sections showed no histopathological alterations whatsoever (Figure 2D).

Duodenum: The duodenum of control untreated rats showed a normal histological structure of the villi, crypts and muscularis layer (Figure 3A). However, the duodenum of rats treated with diclofenac showed focal mucosal necrosis associated with focal inflammatory cell infiltration and edema in the lamina propria, congested mucosal blood vessel and activation of the glands (Figure 3B). A marked amelioration of the histological picture was seen after combining diclofenac with either omeprazole or STW 5. Thus, sections from rats treated with diclofenac/omeprazole showed only mild changes in the lamina propria exhibited as a few inflammatory cell infiltration, slight activation of the glands and slight congestion of blood vessels (Figure 3C) while sections from rats treated with diclofenac/STW 5 showed hardly any histopathological alterations (Figure 3D). The ODS of the lesions in the stomach and duodenum is represented in Figure 4, where it becomes evident that STW 5 was superior to omeprazole in preventing the histological damage induced by diclofenac in both tissues.

The fact that the frequent use of NSAIDs, including diclofenac, is prone to induce GI lesions has been well documented[17]. In alignment with earlier reports, the administration of diclofenac in the given dose over several days resulted in changes in histological as well as associated biochemical parameters in both the stomach and duodenum. The histological changes were evidenced as gastric and duodenal mucosal necrosis, blood vessel congestion and edema as well as inflammatory cells infiltration into lamina propria and submucosa. Similar findings were reported by Devi et al[18].

The GI histological changes were also reflected on the biochemical findings, where diclofenac induced a marked rise in the gastric and duodenal contents of IL-1β and TNF-α, while reducing that of IL-10, indicating a disturbed balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines. The role of these cytokines in the inflammatory process is well established. Thus, TNF-α besides contributing towards the induction of neutrophils to the inflamed mucosa[19], activates the transcription factor, NF-κB, thereby helping to up-regulate many genes involved in inflammatory and immune responses[20]. The other pro-inflammatory cytokine, IL-1β, enhances the production of other pro-inflammatory cytokines in the gut and contributes towards the expression of adhesion molecules on the endothelium[21]. Among the different cells producing the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10, are the regulatory B and T cells which are also involved in inflammation[22]. HO-1 (also designated as heat shock protein-32) is constitutively found in the GI mucosa and becomes up-regulated during inflammation[23]. It inhibits oxidative damage and reduces inflammatory events induced by inflammatory cytokines[24].

In order to reduce the risk of GI injury induced by NSAIDs, adjuvant therapy has been advocated. Towards this end, PPIs have been reported to be very effective. Omeprazole has been effectively used in patients taking NSAIDs in order to heal and prevent recurrence of gastroduodenal injury[25,26]. In support of this, the present study showed its good protective effect against the diclofenac-induced gastroduodenal lesions with marked improvement in the gastric and duodenal levels of the measured cytokines, antiapoptotic protein as well as HO-1 content. Nevertheless, there is some controversy in the literature in this respect. Some authors could not confirm that the drug is able to heal adequately the diclofenac induced GI lesions[3].

The present study also showed that STW 5 had a better protective effect than omeprazole against the histological changes induced by diclofenac, as evidenced by a reduction in the diclofenac-induced gastro-duodenal mucosal necrosis, blood vessel congestion, leukocytic infiltration, and edema. The superiority of STW 5 over omeprazole was previously reported in another experimental model of GI disorders, namely reflux esophagitis[9], where the associated changes in the biochemical parameters were also significantly reduced or prevented.

The histological protective effect of STW 5 was associated with a reduction of the level of the pro-inflammatory cytokines, TNF-α and IL-1β, while increasing that of IL-10. The herbal preparation was previously shown to have a dose-dependent inhibitory effect on TNF-α and/or IL-1β both in vitro[27] and in vivo using rat models of reflux esophagitis[9] and colitis11. Furthermore, STW 5 was reported to have anti-ulcerogenic and mucosal protective effects against indomethacin-induced gastric ulcers in rats[10]. STW 5 has been reported to be clinically effective in functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome[5], conditions that are often associated with inflammatory processes. The fact that STW 5 reduces the level of pro-inflammatory cytokines may at least partly be explained by its potential to inhibit the translocation of nuclear factor-kappa B, which plays an important role in regulating pro-inflammatory gene transcription[28]. This reasoning is further supported by the work of Bertalot et al[29] who showed that activation of Wnt pathway by STW 5 in a zebra fish model has a negative impact on NF-κB signaling in enteric epithelial cells and on the enteric nervous system in general.

The relevance of gastric and/or duodenal HO-1 inflammatory lesions of these tissues is controversial in the literature. The intensity of colitis induced by dextran sulfate sodium was found to be associated with a decreased expression of HO-1[30] while an increased expression was shown in many GI inflammatory conditions, including gastric ulcers[31], colitis[32] and radiation enteritis[33]. In the present study, diclofenac led to a marked decline in the gastric and duodenal HO-1 contents, an effect which was largely prevented by omeprazole. STW 5, however, was mainly effective in the duodenum. Induction of HO-1 was previously reported to have a good protective effect against NSAIDs-induced gastric ulcers. It reduced gastric inflammation, tissue neutrophil activation, and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression caused by indomethacin[34].

Since many of the observed histological changes involve apoptotic mechanisms, and since the Bcl2 family of proteins are critical regulators of the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis, it was important to study the involvement of Bcl2 in our experiments. Diclofenac led to a marked decline in the gastric and duodenal Bcl2 contents, thereby enhancing the apoptotic mechanisms. The effect was largely prevented to the same extent by both STW 5 omeprazole, pointing to their similar anti-apoptotic activity. The anti-apoptotic property of STW 5 was previously reported in detail by Khayyal et al[15].

Collectively, the present findings show that both STW 5 and omeprazole are effective nearly to the same extent in preventing the changes in biochemical parameters associated with the inflammatory response in both the stomach and duodenum of diclofenac treated rats. However, STW 5 was more effective than omeprazole in preventing the histological changes induced by the NSAID, particularly in the duodenum. Furthermore, the study provides pharmacological evidence underlying the clinical usefulness of STW 5 in patients suffering from diclofenac and other NSAID induced gastro-intestinal disorders in placebo-controlled clinical trials[6]. The findings further support more recent clinical and pre-clinical studies showing the efficacy and good tolerability of the herbal preparation[35]. STW 5 may thus represent an effective and safe adjuvant therapy for use in patients taking NSAIDs to guard against the possible occurrence of gastro-duodenal lesions.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), like diclofenac, are prone to induce gastro-duodenal injury on prolonged use, a fact that compromises their clinical usefulness. Continued efforts are being exerted to find agents that could be given alongside the NSAIDs to guard against such injury.

Whereas proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), like omeprazole, are often used to protect against such injury, they are not always effective in protecting against both gastric and duodenal lesions. Moreover, they often exert side effects on their own. Accordingly, the search continues to find agents, such as natural products, that could be safer than PPIs and prove effective against both gastric and duodenal lesions induced by NSAIDs. The herbal preparation, STW 5, has been the focus of our studies for many years, particularly in the field of gastro-intestinal ailments. The preparation has proved to be clinically effective in functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome, as well as experimentally effective against gastric ulcers, ulcerative colitis, and other gastro-intestinal disorders. STW 5 has a wide safety profile. We were therefore highly motivated to test its efficacy in protecting against the gastro-duodenal lesions induced by diclofenac, as an example of a widely used NSAID.

It was important not only to show the efficacy of the herbal preparation in protecting against diclofenac induced lesions, but also to compare its efficacy with that of omeprazole, as an example of a widely used PPI. This would then lead to its clinical trial and possible application as adjuvant therapy for patients who may be sensitive to the use of NSAIDs. STW 5 could then become a valuable and much safer substitute for PPIs.

To achieve these aims experiments were designed to induce gastro-duodenal lesions in rats by feeding them orally with diclofenac for 6 d. The rats were allocated into groups, some receiving concomitantly omeprazole, and others receiving STW 5. At the end of the experimental period, the animals were sacrificed, samples of blood were taken to determine levels of relevant mediators of inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis using ELISA techniques. Sections of gastric and duodenal tissue were prepared for histological examination. All the chosen parameters were considered relevant to the study in question.

Diclofenac led to marked histological changes in both the stomach and duodenum, associated with significant changes in inflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor α, interleukins-1β and 10), in the oxidative stress enzyme, heme oxygenase 1, and in the apoptotic regulator, B-cell lymphoma 2. Both omeprazole and STW 5 in the given doses were comparable in their effects in counteracting the changes in all the biochemical parameters, but STW 5 was much more effective in preventing the histological changes in both the stomach and duodenum. The present results lend further support to the beneficial use of STW 5 in gastro-intestinal disorders. It would be of value to extend the study to other NSAIDs and to further prolong the administration of the NSAID for more than one week. In the present study, giving diclofenac for longer than 6 d led to animal mortality.

STW 5 may offer a much safer alternative to PPIs to help protect the stomach and duodenum from damage in patients under prolonged treatment with NSAIDs. The good clinical tolerability of the herbal preparation which has already been well established in functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome may pave the way to introducing it in preliminary clinical trials as adjuvant therapy in patients undergoing therapy with NSAIDs.

The study is a good example of developing new therapeutic indications for drugs already established on the market, based on well-designed experiments to show their potential efficacy in a new domain. The results obtained warrant further investigations and placebo-controlled studies before being clinically introduced as adjuvant therapy in patients under treatment with drugs that could potentially injure the gastro-intestinal tract.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Egypt

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ciccone MM, Li FY, Serafino A, Tang ZP S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Chan FK, Lanas A, Scheiman J, Berger MF, Nguyen H, Goldstein JL. Celecoxib versus omeprazole and diclofenac in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis (CONDOR): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376:173-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Musumba C, Pritchard DM, Pirmohamed M. Review article: cellular and molecular mechanisms of NSAID-induced peptic ulcers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:517-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (36)] |

| 3. | Dorta G, Nicolet M, Vouillamoz D, Margalith D, Saraga E, Bouzourene H, Häcki WH, Stolte M, Blum AL, Armstrong D. The effects of omeprazole on healing and appearance of small gastric and duodenal lesions during dosing with diclofenac in healthy subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:535-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Simon JP, Evan Prince S. Natural remedies for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced toxicity. J Appl Toxicol. 2017;37:71-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Malfertheiner P. STW 5 (Iberogast) Therapy in Gastrointestinal Functional Disorders. Dig Dis. 2017;35 Suppl 1:25-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mac Lean N, Hübner-Steiner U. [Treatment of drug-induced gastrointestinal disorders. Double-blind study of the effectiveness of Iberogast compared to placebo]. Fortschr Med. 1987;105:239-242. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Rösch W, Liebregts T, Gundermann KJ, Vinson B, Holtmann G. Phytotherapy for functional dyspepsia: a review of the clinical evidence for the herbal preparation STW 5. Phytomedicine. 2006;13 Suppl 5:114-121. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Stanghellini V, Chan FK, Hasler WL, Malagelada JR, Suzuki H, Tack J, Talley NJ. Gastroduodenal Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1380-1392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 818] [Cited by in RCA: 973] [Article Influence: 108.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Abdel-Aziz H, Zaki HF, Neuhuber W, Kelber O, Weiser D, Khayyal MT. Effect of an herbal preparation, STW 5, in an acute model of reflux oesophagitis in rats. J Pharmacol Sci. 2010;113:134-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Khayyal MT, Seif-El-Nasr M, El-Ghazaly MA, Okpanyi SN, Kelber O, Weiser D. Mechanisms involved in the gastro-protective effect of STW 5 (Iberogast) and its components against ulcers and rebound acidity. Phytomedicine. 2006;13 Suppl 5:56-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wadie W, Abdel-Aziz H, Zaki HF, Kelber O, Weiser D, Khayyal MT. STW 5 is effective in dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in rats. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:1445-1453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Scicchitano P, Cameli M, Maiello M, Modesti PA, Muiesane ML, Novo S, Palmieroc P, Sabag PS, Pedrinellih R, Cicconea MM. Nutraceuticals and dyslipidaemia: Beyond the common therapeutics. J Funct Foods. 2014;6:11-32. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Segawa K, Nakazawa S, Tsukamoto Y, Chujoh C, Yamao K, Hase S. Effect of omeprazole on gastric acid secretion in rat: evaluation of dose, duration of effect, and route of administration. Gastroenterol Jpn. 1987;22:413-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kalra BS, Shalini, Chaturvedi S, Tayal V, Gupta U. Evaluation of gastric tolerability, antinociceptive and antiinflammatory activity of combination NSAIDs in rats. Indian J Dent Res. 2009;20:418-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Khayyal MT, Abdel-Naby DH, Abdel-Aziz H, El-Ghazaly MA. A multi-component herbal preparation, STW 5, shows anti-apoptotic effects in radiation induced intestinal mucositis in rats. Phytomedicine. 2014;21:1390-1399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Howarth GS, Francis GL, Cool JC, Xu X, Byard RW, Read LC. Milk growth factors enriched from cheese whey ameliorate intestinal damage by methotrexate when administered orally to rats. J Nutr. 1996;126:2519-2530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Drini M. Peptic ulcer disease and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Aust Prescr. 2017;40:91-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Devi RS, Narayan S, Vani G, Shyamala Devi CS. Gastroprotective effect of Terminalia arjuna bark on diclofenac sodium induced gastric ulcer. Chem Biol Interact. 2007;167:71-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Stallmach A, Giese T, Schmidt C, Ludwig B, Mueller-Molaian I, Meuer SC. Cytokine/chemokine transcript profiles reflect mucosal inflammation in Crohn's disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2004;19:308-315. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Papadakis KA, Targan SR. Role of cytokines in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Annu Rev Med. 2000;51:289-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 524] [Cited by in RCA: 547] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dinarello CA, Wolff SM. The role of interleukin-1 in disease. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:106-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 697] [Cited by in RCA: 666] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Barada KA, Mourad FH, Sawah SI, Khoury C, Safieh-Garabedian B, Nassar CF, Tawil A, Jurjus A, Saadé NE. Up-regulation of nerve growth factor and interleukin-10 in inflamed and non-inflamed intestinal segments in rats with experimental colitis. Cytokine. 2007;37:236-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Barton SG, Rampton DS, Winrow VR, Domizio P, Feakins RM. Expression of heat shock protein 32 (hemoxygenase-1) in the normal and inflamed human stomach and colon: an immunohistochemical study. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2003;8:329-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Alcaraz MJ, Fernández P, Guillén MI. Anti-inflammatory actions of the heme oxygenase-1 pathway. Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9:2541-2551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hawkey CJ, Karrasch JA, Szczepañski L, Walker DG, Barkun A, Swannell AJ, Yeomans ND. Omeprazole compared with misoprostol for ulcers associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Omeprazole versus Misoprostol for NSAID-induced Ulcer Management (OMNIUM) Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:727-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 639] [Cited by in RCA: 564] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Cullen D, Bardhan KD, Eisner M, Kogut DG, Peacock RA, Thomson JM, Hawkey CJ. Primary gastroduodenal prophylaxis with omeprazole for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug users. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:135-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Schneider M, Efferth T, Abdel-Aziz H. Anti-inflammatory Effects of Herbal Preparations STW5 and STW5-II in Cytokine-Challenged Normal Human Colon Cells. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ghosh S, Hayden MS. New regulators of NF-kappaB in inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:837-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 967] [Cited by in RCA: 1057] [Article Influence: 62.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Bertalot T, Schrenk S, Facchinello N, Skobo T, Cenzi C, Dalla Valle L, Abdel-Aziz H, Di Liddo R. WNT signaling activation in the inflammatory process driven by the herbal preparation STW 5. United European Gastroenterology Week Conference; October 15-19; 2016 Vienna, Austria. 2016;P0512. |

| 30. | Khor TO, Huang MT, Kwon KH, Chan JY, Reddy BS, Kong AN. Nrf2-deficient mice have an increased susceptibility to dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11580-11584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 365] [Cited by in RCA: 423] [Article Influence: 23.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Luo C, Chen H, Wang Y, Lin G, Li C, Tan L, Su Z, Lai X, Xie J, Zeng H. Protective effect of coptisine free base on indomethacin-induced gastric ulcers in rats: Characterization of potential molecular mechanisms. Life Sci. 2018;193:47-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Zhu X, Fan WG, Li DP, Kung H, Lin MC. Heme oxygenase-1 system and gastrointestinal inflammation: a short review. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4283-4288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Giriş M, Erbil Y, Doğru-Abbasoğlu S, Yanik BT, Aliş H, Olgaç V, Toker GA. The effect of heme oxygenase-1 induction by glutamine on TNBS-induced colitis. The effect of glutamine on TNBS colitis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:591-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Uc A, Zhu X, Wagner BA, Buettner GR, Berg DJ. Heme oxygenase-1 is protective against nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced gastric ulcers. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54:471-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Cremonini F. Standardized herbal treatments on functional bowel disorders: moving from putative mechanisms of action to controlled clinical trials. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26:893-900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |