Published online May 28, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i20.2489

Peer-review started: February 6, 2019

First decision: March 14, 2019

Revised: March 27, 2019

Accepted: April 19, 2019

Article in press: April 20, 2019

Published online: May 28, 2019

Processing time: 116 Days and 5 Hours

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) is suggested to be an early and important step in tumor progression toward metastasis, but its prognostic value and genetic mechanisms in colorectal cancer (CRC) have not been well investigated.

To investigate the prognostic value of LVI in CRC and identify the associated genomic alterations.

We performed a retrospective analysis of 1219 CRC patients and evaluated the prognostic value of LVI for overall survival by the Kaplan-Meier method and multivariate Cox regression analysis. We also performed an array-based comparative genomic hybridization analysis of 47 fresh CRC samples to examine the genomic alterations associated with LVI. A decision tree model was applied to identify special DNA copy number alterations (DCNAs) for differentiating between CRCs with and without LVI. Functional enrichment and protein-protein interaction network analyses were conducted to explore the potential molecular mechanisms of LVI.

LVI was detected in 150 (12.3%) of 1219 CRCs, and the presence was positively associated with higher histological grade and advanced tumor stage (both P < 0.001). Compared with the non-LVI group, the LVI group showed a 1.77-fold (95% confidence interval: 1.40-2.25, P < 0.001) increased risk of death and a significantly lower 5-year overall survival rate (P < 0.001). Based on the comparative genomic hybridization data, 184 DCNAs (105 gains and 79 losses) were identified to be significantly related to LVI (P < 0.05), and the majority were located at 22q, 17q, 10q, and 6q. We further constructed a decision tree classifier including seven special DCNAs, which could distinguish CRCs with LVI from those without it at an accuracy of 95.7%. Functional enrichment and protein-protein interaction network analyses revealed that the genomic alterations related to LVI were correlated with inflammation, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, angiogenesis, and matrix remodeling.

LVI is an independent predictor for survival in CRC, and its development may correlate with inflammation, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, angiogenesis, and matrix remodeling.

Core tip: Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) is suggested to be an obligatory step in tumor progression toward metastasis, but its genetic mechanisms in colorectal cancer (CRC) have not been fully understood. This study showed that LVI was significantly associated with features of aggressive tumors and reduced survival in CRC, and its development might correlate with inflammation, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, angiogenesis, and matrix remodeling. We also constructed a DNA copy number alteration classifier that could estimate the LVI status with high accuracy, which might contribute to the management of CRC.

- Citation: Jiang HH, Zhang ZY, Wang XY, Tang X, Liu HL, Wang AL, Li HG, Tang EJ, Lin MB. Prognostic significance of lymphovascular invasion in colorectal cancer and its association with genomic alterations. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(20): 2489-2502

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i20/2489.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i20.2489

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a major public health problem worldwide, with 1.4 million new cases and 0.7 million deaths estimated each year[1]. Surgical excision is the mainstay of treatment for CRC; however, 30%-50% of patients develop local tumor recurrence or metastasis even after potentially curative surgery[2]. Currently, the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system is a universal guideline for prognosis prediction and treatment decision-making[3]. Nevertheless, heterogeneous survival rates in patients with the same stage of disease have been noted[4,5]. It has been gradually recognized that some other clinicopathological features may contribute to a more individual prediction of prognosis in CRC, such as age, systemic inflammation, tumor grade, and lymphovascular invasion (LVI)[6,7].

LVI is a histopathological finding defined by the presence of tumor cells within endothelium-lined lymphatic or vascular channels[8], with a presence of 10.0%-89.5% in CRC[9-13]. Indeed, LVI is an essential and important step in lymph node metastasis and systemic dissemination of cancer cells, and it is considered to increase the risk for micrometastases in localized carcinoma[14,15]. The unfavorable prognostic significance of LVI has been supported by studies in various cancers, such as breast cancer, gastric cancer, and prostatic cancer[11,16-18]. Furthermore, some studies have been conducted to explore the potential mechanisms underlying this association. Pan et al[19] reported that cyclooxygenase-2 up-regulates chemokine CC receptor 7 via EP2/EP4 receptor signaling pathways to enhance LVI of breast cancer cells. Tatti et al[20] suggested that matrix metalloproteinase 16 (MMP16) mediates a proteolytic switch to promote cell-cell adhesion and LVI in melanoma. A study by Mannelqvist et al[21] found that overexpression of MMP3 and collagen VIII in endometrial cancer correlates closely with the presence of LVI. However, the genetic mechanisms of LVI in CRC have not been well investigated.

We performed a retrospective analysis in 1219 CRC patients to evaluate the presence of LVI, as well as its relationship with classical clinicopathological parameters and patients’ outcome. We also analyzed the genomic profiles of 47 CRC samples using array-based comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) to identify the genomic alterations associated with LVI. Our findings may provide further insight into the biology of LVI in CRC and offer novel targets for the treatment and prevention of cancer dissemination.

Patients with newly diagnosed, histologically confirmed colorectal adenocarcinoma (n = 1219) were included in this retrospective study. Among them, 1005 were recruited from Ruijin Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine from January 2008 to December 2010, and 214 were enrolled from Zhuji People’s Hospital of Zhejiang Province between January 2007 and December 2010. All patients underwent standard surgical treatment and were retrospectively reviewed with a minimum 5-year postoperative follow-up. Patients with recurrent disease or another malignancy or those whose present status could not be ascertained were excluded from the study. Written consent was obtained from all patients, and their information was stored in the hospital database and used for research. Clinical and pathological data were abstracted from patients’ medical records, including gender, age, tumor site, differentiation, stage, and LVI status. Tumor was staged according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM classification (version 8.0) and graded according to the 2010 World Health Organization classification. LVI was defined by the presence of malignant cells within endothelium-lined spaces on hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections[8].

Forty-seven surgically removed sporadic colorectal adenocarcinoma specimens were obtained from Yangpu Hospital Affiliated to Tongji University between June 2017 and December 2018 and were analyzed using array-based CGH. All specimens were evaluated by at least two pathologists and were stored at -80 °C until assay. Of these, 21 tumors presented with LVI, and the remaining 26 with non-LVI served as controls. The patients included 17 women and 30 men with ages ranging from 45 to 88 years; six cases were stage I, six stage II, 17 stage III, and 18 stage IV. None of the patients had a history of another malignancy or inflammatory bowel disease. There was no significant difference in gender, age, tumor site, differentiation, or stage between the case and control groups. Written informed consent was obtained before specimen collection, and this study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Yangpu Hospital (LL-2019-SCI-001).

DNA was extracted from frozen tumors using the QIAmp Tissue Kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany). Cytogenomic microarray analysis was performed using the Agilent SurePrint G3 Cancer CGH + SNP 4 × 180K Array, a cancer-specific CGH + SNP microarray designed by Cancer Genomics Consortium (www.chem-agilent.com/ pdf/59909183en_lo_CGH+SNP_Cancer.pdf) (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United States). Arrays were scanned with the Agilent DNA Microarray Scanner with Surescan High-Resolution Technology. Whole genome microarray data were analyzed using Agilent CytoGenomics 2.5 software to identify DNA copy number alterations (DCNAs). The global ADM2 algorithm with a threshold 6.0 and aberration filter for a minimum of three consecutive probes per region were applied. Genomic linear positions were given relative to NCBI build 37 (hg19, http:// genome.ucsc.edu).

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 22.0 (Armonk, NY, United States) and R version 3.2.0 (R foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the difference in the distribution of categorical variables. Differences in continuous variables were tested with Student’s t-test. The endpoint of the retrospective study was overall survival (OS), which was calculated from the date of diagnosis to death from any cause or the last follow-up. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. A multivariate Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and to identify independent predictors for 5-year OS.

The CGH data were shown for the autosomes only, and the sex chromosomes were not included in this analysis. The frequencies of DCNAs between CRCs with and without LVI were compared using Pearson’s χ2 test, with P < 0.05 considered significant. A decision-tree model J48 classifier attached to WEKA http:// www.cs.waikato.ac.nz/ml/weka/ was further applied to identify the DCNAs for differentiating between the two groups. In order to explore the molecular mechanism of LVI in CRC, the genes located at the significant DCNAs were mapped into the DAVID database (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/). Gene ontology analysis was applied to reveal functions of gene products from three aspects: Biological process, cellular component, and molecular function. Kyoto encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway analysis was used to identify relevant biological pathways. Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (http://string-db.org) was used to investigate the interactive relationship among the acquired genes (confidence score > 0.95), and the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network was visualized using Cytoscape software (San Diego, CA, United States) (http://www.cytoscape.org). To identify the hub genes in the network, three centrality methods, including closeness, degree, and eigenvector centrality[22], were evaluated with the Cytoscape CytoNCA plugin. For all analyses, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Of the 1219 CRC patients included in the retrospective analysis, 714 (58.6%) were male and 505 (41.4%) were female, with a median age of 62 years (range, 21-92 years). There were 569 (46.7%) colon cancers and 650 (53.3%) rectal cancers. Histologically, 894 (73.3%) cases were well or moderately differentiated, and 325 (26.7%) were poorly differentiated or mucinous. According to TNM classification, 219 (18.0%) patients were stage I, 398 (32.6%) stage II, 422 (34.6%) stage III, and 180 (14.8%) stage IV. LVI was detected in 150 tumors, with a presence of 12.3% (10.5%-14.2%). The comparison of clinicopathological features between CRCs with and without LVI showed that LVI group was more likely to be poorly differentiated or mucinous (P < 0.001) and its presence progressively increased with advancing tumor stage (5.5% in stage I, 7.5% in stage II, 15.2% in stage III, and 24.4% in stage IV, respectively, P < 0.001), whereas no significant correlation was detected for gender, age, or tumor site (all P > 0.05) (Table 1).

| Characteristic | LVI, n = 150 | Non-LVI, n = 1069 | P value |

| No. of patients (%) | No. of patients (%) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 93 (62.0) | 621 (58.1) | |

| Female | 57 (38.0) | 448 (41.9) | 0.377 |

| Age in yr | |||

| ≤ 65 | 87 (58.0) | 629 (58.8) | |

| > 65 | 63 (42.0) | 440 (41.2) | 0.860 |

| Tumor site | |||

| Colon | 72 (48.0) | 497 (46.5) | |

| Rectum | 78 (52.0) | 572 (53.5) | 0.793 |

| Histological differentiation | |||

| Well/moderately | 79 (52.7) | 815 (76.2) | |

| Poorly/mucinous | 71 (47.3) | 254 (23.8) | < 0.001 |

| TNM stage | |||

| I | 12 (8.0) | 207 (19.4) | |

| II | 30 (20.0) | 368 (34.4) | |

| III | 64 (42.7) | 358 (33.5) | |

| IV | 44 (29.3) | 136 (12.7) | < 0.001 |

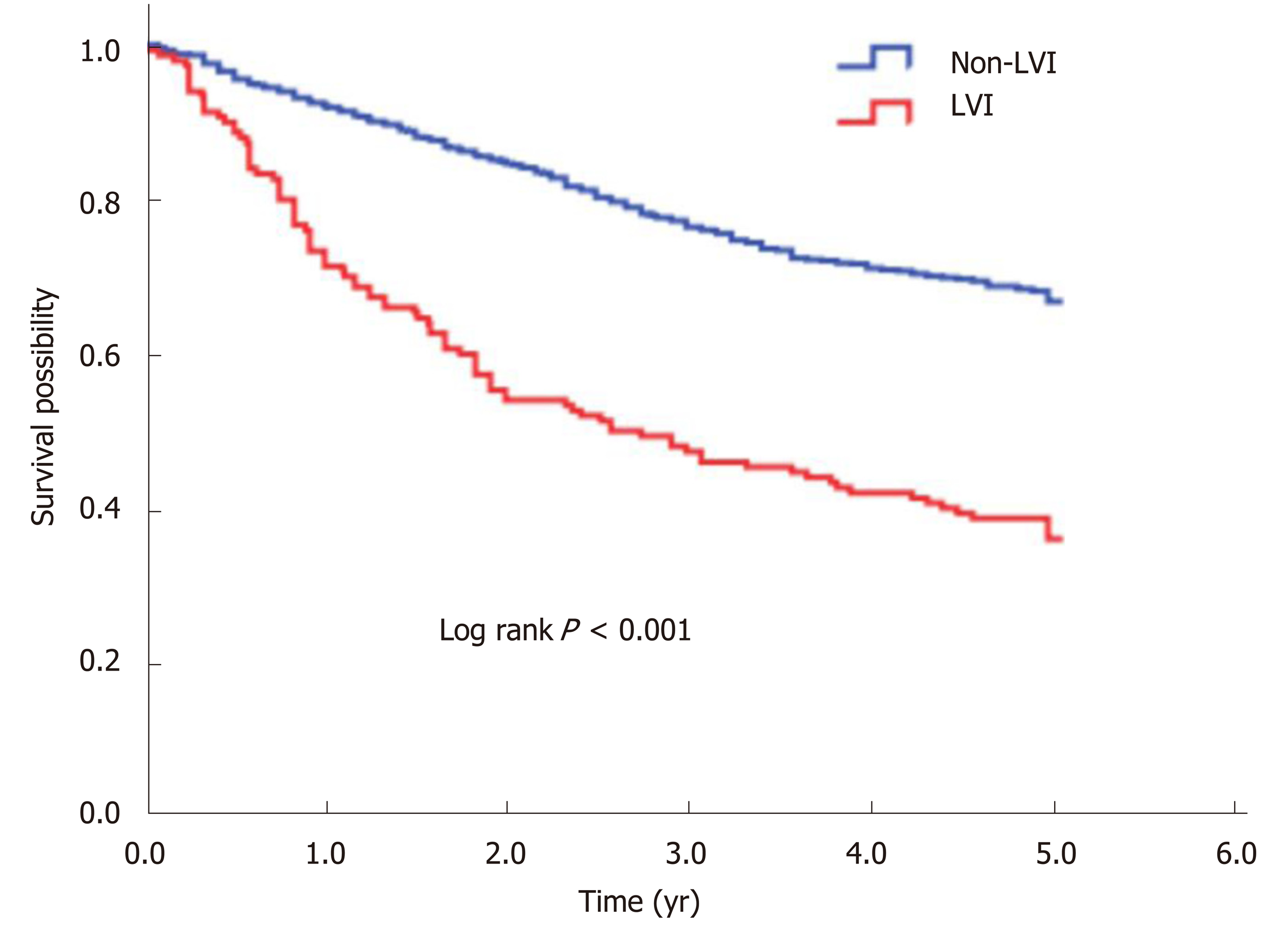

The 5-year OS rate of the study cohort was 63.0%. We analyzed the association of LVI with survival in a multivariate Cox analysis and found that LVI was an independent predictor for 5-year OS after controlling for gender, age, tumor site, differentiation, and stage (Table 2). Compared with the non-LVI group, the LVI group showed a 1.77-fold (95%CI: 1.40-2.25, P < 0.001) increased risk of death and a significantly lower 5-year OS rate (66.8% vs 36.0%, log rank P < 0.001) (Figure 1).

| Characteristic | HR (95%CI) | P value |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1 (Reference) | |

| Female | 0.93 (0.77-1.13) | 0.481 |

| Age in yr | ||

| ≤ 65 | 1 (Reference) | |

| > 65 | 1.93 (1.60-2.33) | < 0.001 |

| Tumor site | ||

| Colon | 1 (Reference) | |

| Rectum | 0.94 (0.78-1.13) | 0.497 |

| Histological differentiation | ||

| Well/moderately | 1 (Reference) | |

| Poorly/mucinous | 1.51 (1.24-1.85) | < 0.001 |

| TNM stage | ||

| I | 1 (Reference) | |

| II | 1.63 (1.07-2.47) | 0.022 |

| III | 3.31 (2.24-4.90) | < 0.001 |

| IV | 11.88 (7.94-17.77) | < 0.001 |

| LVI | ||

| Negative | 1 (Reference) | |

| Positive | 1.77 (1.40-2.25) | < 0.001 |

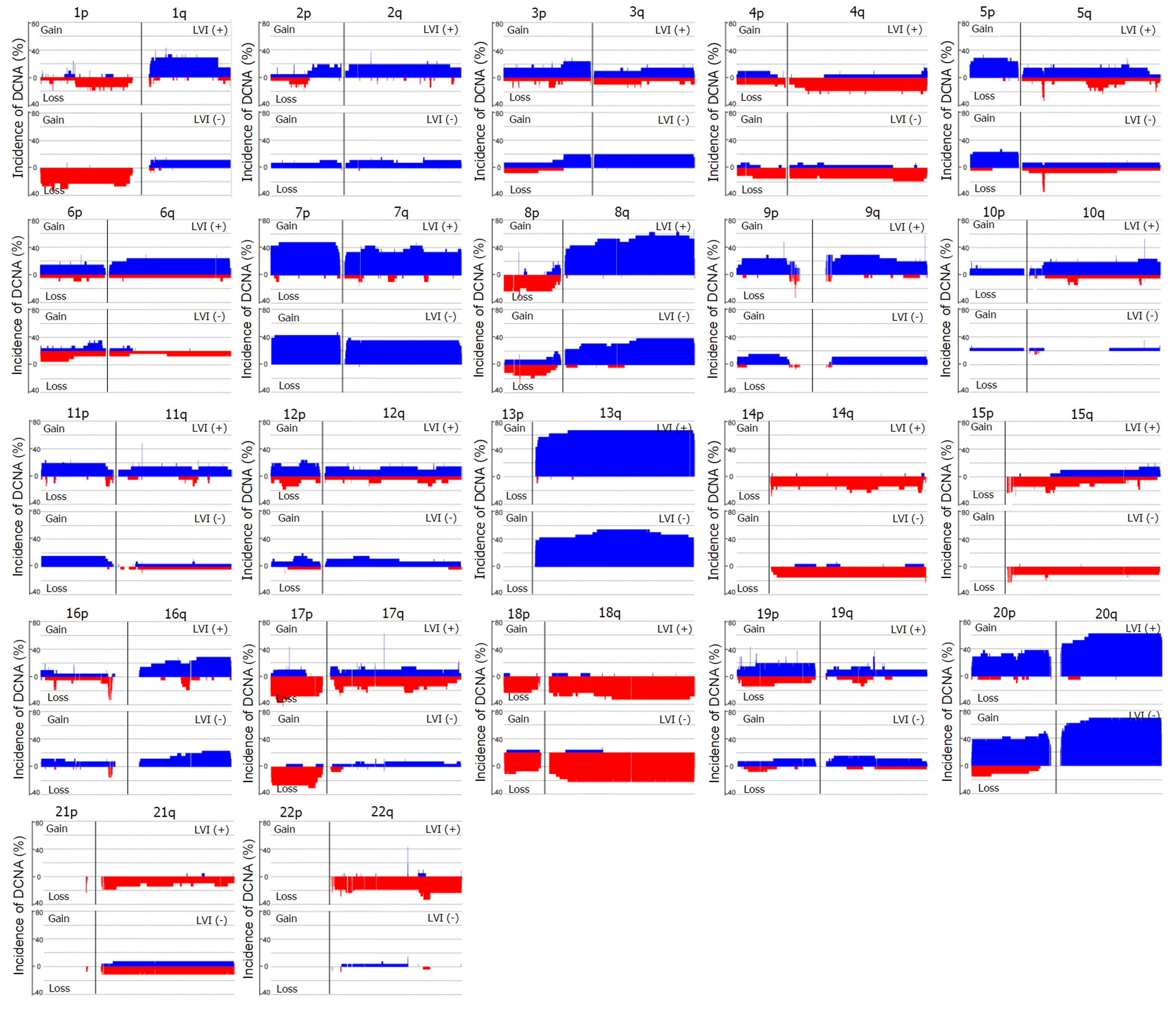

Array-based CGH was performed on 47 CRC samples. Although there were differences in the DCNAs between each sample, gains were commonly observed at 20q (70.2% of 47 samples), 13q (59.6%), 8q (55.3%), 7p (51.1%), and 7q (51.1%), while losses were frequently detected at 5q (51.1%), 15q (42.6%), 14q (40.4%), 18q (40.4%), and 17p (36.2%). The comparison of CGH data between CRCs with and without LVI was summarized in Figure 2. One hundred eight-four DCNAs (105 gains and 79 losses) exhibited a significant difference in their frequencies between the two groups (P < 0.05), and the majority were located at 22q (29.3% of 184 DCNAs), 17q (16.3%), 10q (13.0%), and 6q (7.1%). To construct a classifier that could effectively detect LVI, the 184 DCNAs were further input into a decision-tree model. Tumors with LVI were distinguished from those without it at a 95.7% accuracy rate by examining seven special DCNAs, including gains at chr6:95148725-95193920, chr14:106113380-106135655, chr7:159075079-159118566, chr8:145737350-145741217, and chr17:48266096-48267750, and losses at chr17:30770711-30859316 and chr9:43469486-43659512 (Figure 3). Moreover, a sensitivity of 95.7% and a specificity of 94.7% were obtained.

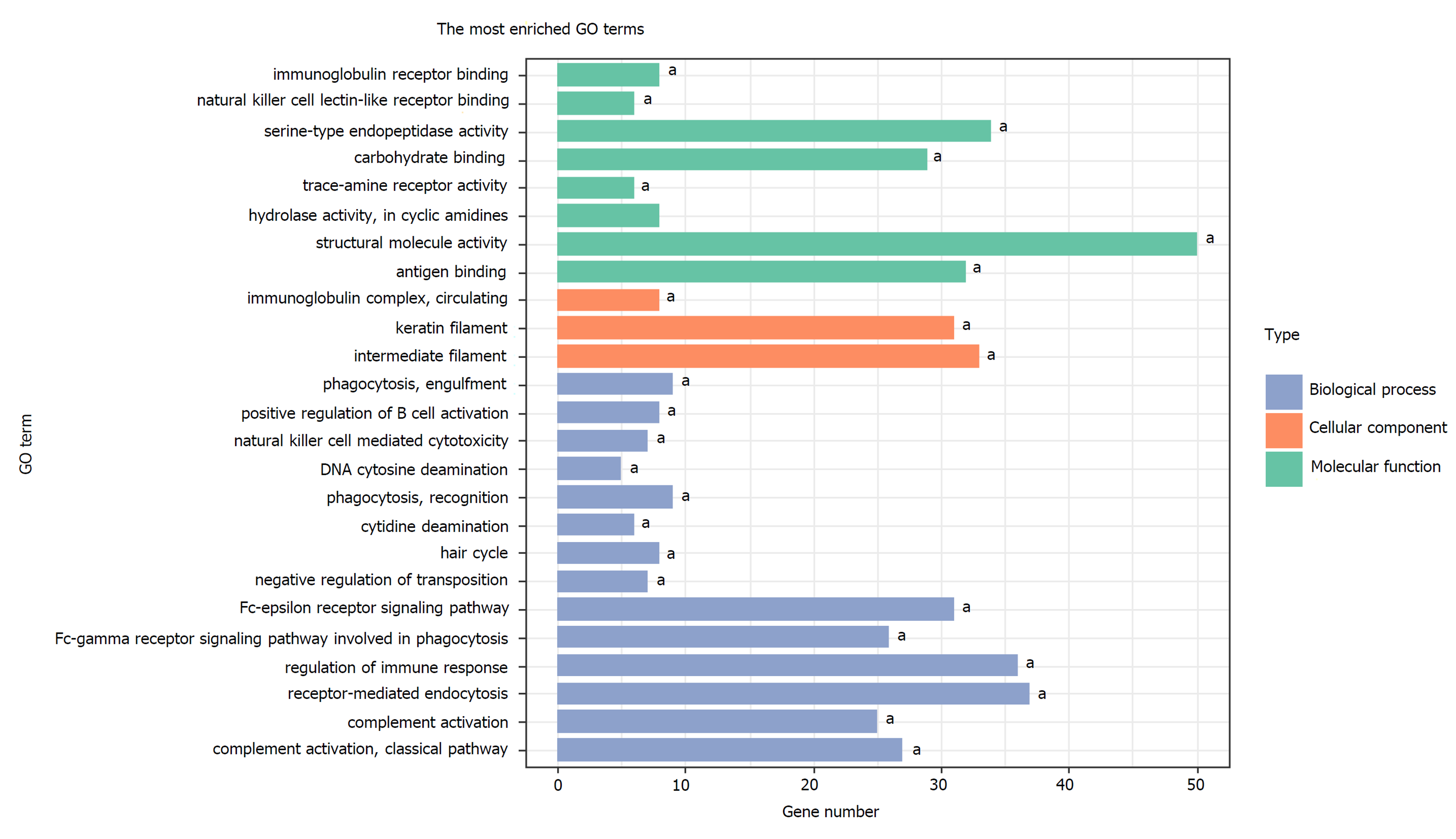

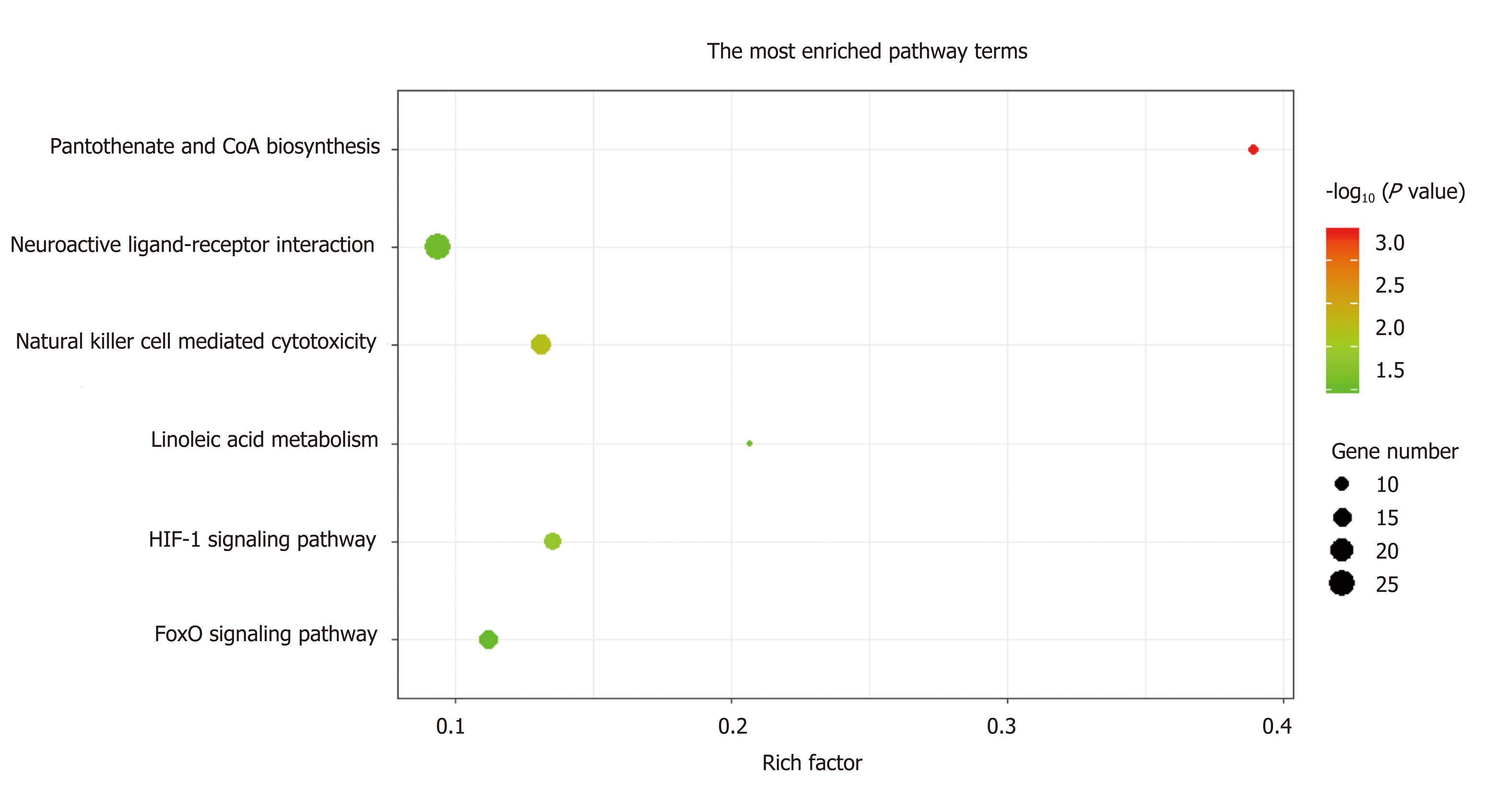

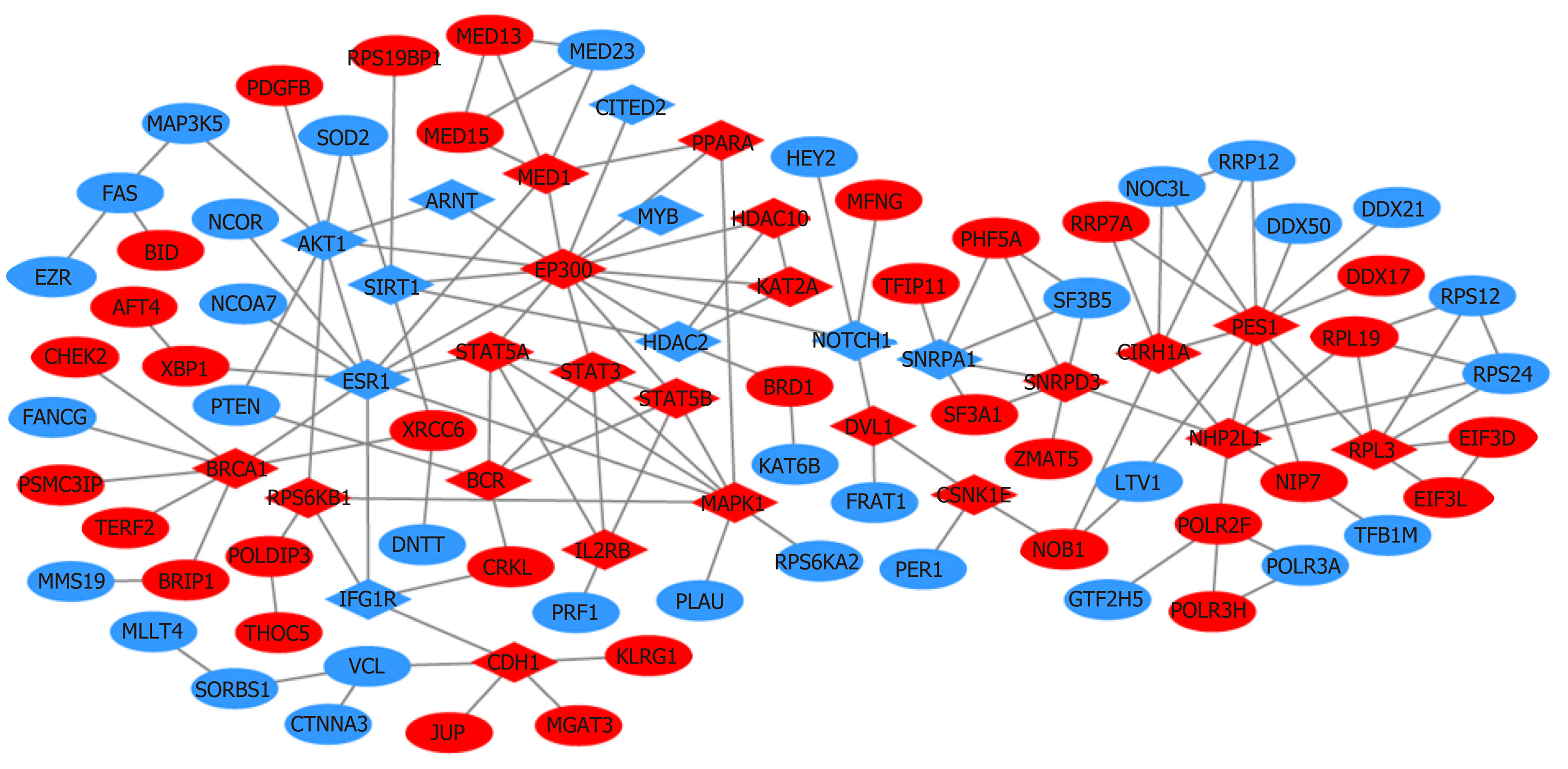

A total of 1784 genes were identified in the 184 DCNAs correlated with LVI. To explore the biological relevance of these genes, we performed functional enrichment and PPI network analyses. Gene ontology analysis showed that these genes were significantly enriched in biological process terms such as complement activation, regulation of immune response, and negative regulation of transposition; cellular component terms such as immunoglobulin complex; as well as molecular function terms such as antigen binding and immunoglobulin receptor binding (Figure 4). Pathway analysis revealed that these genes were concentrated in pathways of natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity, hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) signaling, and fork-head box O signaling (Figure 5). Furthermore, based on the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes database, a PPI network with 97 nodes and 142 edges was constructed (Figure 6). The top 20 nodes with higher PPI scores, respectively, identified by closeness, degree, and eigenvector were selected as hub genes (Table 3). After eliminating the repeated ones, 31 hub genes were obtained, including EP300, STAT3, SIRT1, RPS6KB1, MAPK1, etc.

| Rank | Closeness | Degree | Eigenvector | |||

| Gene | Value | Gene | Value | Gene | Value | |

| 1 | EP300 | 0.256684 | EP300 | 15 | EP300 | 0.481394 |

| 2 | NOTCH1 | 0.241814 | PES1 | 11 | ESR1 | 0.320964 |

| 3 | ESR1 | 0.240000 | ESR1 | 10 | STAT5A | 0.297293 |

| 4 | AKT1 | 0.227488 | MAPK1 | 8 | STAT3 | 0.285113 |

| 5 | DVL1 | 0.225352 | AKT1 | 8 | MAPK1 | 0.269273 |

| 6 | STAT5A | 0.223776 | BRCA1 | 7 | STAT5B | 0.240224 |

| 7 | MED1 | 0.219680 | NHP2L1 | 7 | AKT1 | 0.221299 |

| 8 | STAT3 | 0.213808 | STAT5A | 6 | MED1 | 0.202291 |

| 9 | STAT5B | 0.213333 | MED1 | 6 | PPARA | 0.169136 |

| 10 | SIRT1 | 0.212860 | STAT3 | 6 | BCR | 0.166509 |

| 11 | PPARA | 0.210526 | CIRH1A | 6 | HDAC2 | 0.164826 |

| 12 | HDAC2 | 0.209607 | SNRPD3 | 6 | IL2RB | 0.151029 |

| 13 | ARNT | 0.209607 | RPL3 | 6 | KAT2A | 0.139521 |

| 14 | CSNK1E | 0.209150 | STAT5B | 5 | HDAC10 | 0.139521 |

| 15 | HDAC10 | 0.206452 | BCR | 5 | SIRT1 | 0.137321 |

| 16 | KAT2A | 0.206452 | SIRT1 | 5 | ARNT | 0.124740 |

| 17 | MYB | 0.204691 | HDAC2 | 5 | RPS6KB1 | 0.105985 |

| 18 | CITED2 | 0.204691 | CDH1 | 5 | NOTCH1 | 0.094497 |

| 19 | IGF1R | 0.204255 | SNRPA1 | 5 | IGF1R | 0.087082 |

| 20 | MAPK1 | 0.202105 | RPS6KB1 | 4 | MYB | 0.085425 |

LVI is a common histopathological finding and serves as an unfavorable prognostic factor in many cancers[11,16,17,23]. In terms of tumor biology, invasion of tumor cells into vascular channels is suggested to be an obligatory step in tumor progression toward metastasis[14,24]. According to previous studies, the presence of LVI in CRC varied widely from 10.0% to 89.5%[9-13], which might be caused by the differences in diagnostic techniques and patient populations included in different studies[8,25]. In the current study, LVI was observed in 150 (12.3%) of 1219 CRCs, and the presence increased with tumor stage from 5.5% in stage I to 24.4% in stage IV. Similar to other studies, our data showed that LVI was closely related to the features of aggressive tumors, such as higher histological grade and advanced tumor stage[11,18]. Thus, some findings suggested that the presence of LVI should be an indication of more extensive surgical resection[26,27]. Our study also confirmed that LVI was an independent predictor for survival in CRC, as shown by multivariate prognostic analysis. Therefore, it is important to explore the genetic mechanisms of LVI, which may provide novel diagnostic biomarkers or therapeutic targets for CRC.

Although various studies have reported gene signatures related to metastasis in CRC[28-30], much is unknown about the molecular pathogenesis of LVI; an early and critical step in metastasis. We performed an array-based CGH analysis of 47 CRC samples and found the most frequent aberrations were detected at 20q, 18q, 17p, 15q, 14q, 13q, 8q, 7p, 7q, and 5q, consistent with previous reports[31,32]. The comparison between CRCs with and without LVI revealed that 184 DCNAs were significantly associated with the presence of LVI, and more than half of them were found at 22q, 17q, 10q, and 6q. Knösel et al[33] and Nakao et al[34] indicated that the DCNAs associated with CRC metastases were mostly located at 22q, 20q, 17q, 15q, 10q, 8p, 8q, and 6q. These findings suggested the emergence of multiple chromosomal aberrations at the transition from LVI to metastasis formation. Furthermore, a decision tree classifier was applied to these significant DCNAs. It can allow for an automatic differentiation of LVI or non-LVI CRCs by checking seven special DCNAs, with a high accuracy of 95.7%. This is the first report of the development of a DCNA classifier in order to estimate the LVI status of each tumor for optimal diagnosis, thus contributing to personalized CRC management. However, the number of tumors examined in this study was limited, and large-scale studies might identify the DCNAs with a stronger impact on the evaluation of LVI status.

In this study, a total of 1784 genes were identified in the 184 DCNAs related to LVI in CRC. With the identified genes, we performed functional enrichment analyses and found that they were significantly enriched in immune response and inflammation mediated by immunoglobulins and immune complexes. Previous studies have showed that perivascular lymphocytic infiltration is strongly associated with the presence of LVI and aggressive tumor behavior[21,35]. Our findings supported the involvement of perivascular inflammation in the process of LVI, also suggesting the importance of inflammation in cancer progression[36,37]. Additionally, we constructed a PPI network and screened out some key genes, such as EP300, STAT3, SIRT1, and RPS6KB1, which have been related to epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), active angiogenesis, or matrix remodeling. In the PPI network, EP300 possesses the highest values of all three centrality measures. It functions as transcriptional coactivator for some nuclear proteins, such as HIF-1α, thus participating in hypoxia-induced invasion and EMT process[38]. STAT3 is a central cytoplasmic transcription factor and suggested to be involved in tumor proliferation, apoptosis, invasion, and migration, by regulating the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and MMPs[39]. SIRT1 encodes an NAD-dependent deacetylase and acts as a positive regulator of EMT, tumor vascularization, and metastatic growth[40]. RPS6KB1 is reported to be involved in tumor growth and angiogenesis through HIF-1α and VEGF expression[41]. The present study indicated that these genes might play an important role in the development of LVI and further our understanding of the targets for early metastatic spread in CRC.

In conclusion, we identified that LVI was significantly associated with features of aggressive tumors and reduced survival in CRC, and constructed a DCNA classifier that could estimate the LVI status of CRC with high accuracy. Our results also indicated that the genomic alterations related to LVI were correlated with inflammation, EMT, angiogenesis, and matrix remodeling. These findings might contribute to an improved understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved in LVI and provide valuable information for better management of CRC.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide. It has been reported that many clinicopathological factors may contribute to the prognostic prediction of cancer patients except tumor-node-metastasis stage, including lymphovascular invasion (LVI). LVI is suggested to be an early and critical step in lymph node metastasis and systemic dissemination of cancer cells. However, the prognostic value and genetic mechanisms of LVI in CRC have not been well investigated so far.

LVI is a common histopathological finding in cancers and is considered to be an important step in cancer progression toward metastasis, but its genetic mechanisms in CRC have yet to be fully understood. Our study may offer new insight into the biology of LVI and provide valuable information for better management of CRC.

The objective of this study was to investigate the prognostic value of LVI in CRC and identify the genomic alterations associated with LVI using array-based comparative genomic hybridization (CGH).

We performed a retrospective analysis in a population of 1219 CRC patients to evaluate the presence of LVI, as well as its relationship with classical clinicopathological parameters and patient’s outcome. Kaplan-Meier method and Cox regression model were used for overall survival analysis. We also analyzed the genomic profiles of 47 CRC samples using CGH to identify the genomic alterations associated with LVI. A decision tree model classifier was applied to the CGH data to identify special DNA copy number alterations (DCNAs) for differentiating CRCs with and without LVI. We further performed functional enrichment and protein-protein interaction network analyses to explore the potential molecular mechanisms of LVI in CRC.

Of the 1219 CRC patients included in the retrospective analysis, 150 (12.3%) cases presented with LVI. The comparison of clinicopathological characteristics between CRCs with and without LVI found that the presence of LVI was significantly with higher histological grade and advanced tumor stage (both P < 0.001). Survival analysis showed that LVI was an independent predictor for overall survival in CRC, with a hazard ratio of 1.77 (95% confidence interval: 1.40-2.25, P < 0.001). Based on the CGH data of 47 CRC samples, 184 DCNAs (105 gains and 79 losses) were found to exhibit a significant difference in the frequencies between LVI and non-LVI groups (P < 0.05), and the majority were located at 22q, 17q, 10q, and 6q. We further performed decision tree analysis and constructed a classifier that could distinguish CRCs with LVI from those without it at an accuracy of 95.7% by examining seven special DCNAs. Functional enrichment analyses showed that the genomic alterations related to LVI were correlated with immune response and inflammation. Additionally, we constructed a protein-protein interaction network and screened out some key genes, such as EP300, STAT3, SIRT1, and RPS6KB1, which were involved in epithelial-mesenchymal transition, active angiogenesis or matrix remodeling.

The present study identified that LVI was significantly associated with features of aggressive tumors and reduced survival in CRC, and its development might correlate with inflammation, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, angiogenesis, and matrix remodeling.

Our study preliminarily explored the genetic alterations associated with LVI in CRC, which might offer novel targets for the treatment and prevention of cancer dissemination. Further studies are required to confirm our findings and to clarify the precise mechanism involved in LVI.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gkekas I, Parellada CM S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18694] [Cited by in RCA: 21368] [Article Influence: 2136.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Lieberman DA, Rex DK, Winawer SJ, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, Levin TR. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: A consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:844-857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1367] [Cited by in RCA: 1445] [Article Influence: 111.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ueno H, Mochizuki H, Akagi Y, Kusumi T, Yamada K, Ikegami M, Kawachi H, Kameoka S, Ohkura Y, Masaki T, Kushima R, Takahashi K, Ajioka Y, Hase K, Ochiai A, Wada R, Iwaya K, Shimazaki H, Nakamura T, Sugihara K. Optimal colorectal cancer staging criteria in TNM classification. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1519-1526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Schneider NI, Langner C. Prognostic stratification of colorectal cancer patients: Current perspectives. Cancer Manag Res. 2014;6:291-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Eschrich S, Yang I, Bloom G, Kwong KY, Boulware D, Cantor A, Coppola D, Kruhøffer M, Aaltonen L, Orntoft TF, Quackenbush J, Yeatman TJ. Molecular staging for survival prediction of colorectal cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3526-3535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mehrkhani F, Nasiri S, Donboli K, Meysamie A, Hedayat A. Prognostic factors in survival of colorectal cancer patients after surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11:157-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | McMillan DC. Systemic inflammation, nutritional status and survival in patients with cancer. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2009;12:223-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 631] [Cited by in RCA: 754] [Article Influence: 47.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Harris EI, Lewin DN, Wang HL, Lauwers GY, Srivastava A, Shyr Y, Shakhtour B, Revetta F, Washington MK. Lymphovascular invasion in colorectal cancer: An interobserver variability study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:1816-1821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Inoue T, Mori M, Shimono R, Kuwano H, Sugimachi K. Vascular invasion of colorectal carcinoma readily visible with certain stains. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:34-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Abdulkader M, Abdulla K, Rakha E, Kaye P. Routine elastic staining assists detection of vascular invasion in colorectal cancer. Histopathology. 2006;49:487-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lim SB, Yu CS, Jang SJ, Kim TW, Kim JH, Kim JC. Prognostic significance of lymphovascular invasion in sporadic colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:377-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ouchi K, Sugawara T, Ono H, Fujiya T, Kamiyama Y, Kakugawa Y, Mikuni J, Tateno H. Histologic features and clinical significance of venous invasion in colorectal carcinoma with hepatic metastasis. Cancer. 1996;78:2313-2317. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Sternberg A, Amar M, Alfici R, Groisman G. Conclusions from a study of venous invasion in stage IV colorectal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:17-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Barresi V, Reggiani Bonetti L, Vitarelli E, Di Gregorio C, Ponz de Leon M, Barresi G. Immunohistochemical assessment of lymphovascular invasion in stage I colorectal carcinoma: Prognostic relevance and correlation with nodal micrometastases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:66-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nathanson SD, Kwon D, Kapke A, Alford SH, Chitale D. The role of lymph node metastasis in the systemic dissemination of breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:3396-3405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rakha EA, Martin S, Lee AH, Morgan D, Pharoah PD, Hodi Z, Macmillan D, Ellis IO. The prognostic significance of lymphovascular invasion in invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2012;118:3670-3680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dicken BJ, Graham K, Hamilton SM, Andrews S, Lai R, Listgarten J, Jhangri GS, Saunders LD, Damaraju S, Cass C. Lymphovascular invasion is associated with poor survival in gastric cancer: An application of gene-expression and tissue array techniques. Ann Surg. 2006;243:64-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cheng L, Jones TD, Lin H, Eble JN, Zeng G, Carr MD, Koch MO. Lymphovascular invasion is an independent prognostic factor in prostatic adenocarcinoma. J Urol. 2005;174:2181-2185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pan MR, Hou MF, Chang HC, Hung WC. Cyclooxygenase-2 up-regulates CCR7 via EP2/EP4 receptor signaling pathways to enhance lymphatic invasion of breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:11155-11163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tatti O, Gucciardo E, Pekkonen P, Holopainen T, Louhimo R, Repo P, Maliniemi P, Lohi J, Rantanen V, Hautaniemi S, Alitalo K, Ranki A, Ojala PM, Keski-Oja J, Lehti K. MMP16 Mediates a Proteolytic Switch to Promote Cell-Cell Adhesion, Collagen Alignment, and Lymphatic Invasion in Melanoma. Cancer Res. 2015;75:2083-2094. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Mannelqvist M, Stefansson IM, Bredholt G, Hellem Bø T, Oyan AM, Jonassen I, Kalland KH, Salvesen HB, Akslen LA. Gene expression patterns related to vascular invasion and aggressive features in endometrial cancer. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:861-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jeong H, Mason SP, Barabási AL, Oltvai ZN. Lethality and centrality in protein networks. Nature. 2001;411:41-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3646] [Cited by in RCA: 2662] [Article Influence: 110.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Higgins KA, Chino JP, Ready N, D'Amico TA, Berry MF, Sporn T, Boyd J, Kelsey CR. Lymphovascular invasion in non-small-cell lung cancer: Implications for staging and adjuvant therapy. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:1141-1147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nofech-Mozes S, Ackerman I, Ghorab Z, Ismiil N, Thomas G, Covens A, Khalifa MA. Lymphovascular invasion is a significant predictor for distant recurrence in patients with early-stage endometrial endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:912-917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Betge J, Pollheimer MJ, Lindtner RA, Kornprat P, Schlemmer A, Rehak P, Vieth M, Hoefler G, Langner C. Intramural and extramural vascular invasion in colorectal cancer: Prognostic significance and quality of pathology reporting. Cancer. 2012;118:628-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Choi JY, Jung SA, Shim KN, Cho WY, Keum B, Byeon JS, Huh KC, Jang BI, Chang DK, Jung HY, Kong KA; Korean ESD Study Group. Meta-analysis of predictive clinicopathologic factors for lymph node metastasis in patients with early colorectal carcinoma. J Korean Med Sci. 2015;30:398-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | del Casar JM, Corte MD, Alvarez A, García I, Bongera M, González LO, García-Muñiz JL, Allende MT, Astudillo A, Vizoso FJ. Lymphatic and/or blood vessel invasion in gastric cancer: Relationship with clinicopathological parameters, biological factors and prognostic significance. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134:153-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Takayama T, Miyanishi K, Hayashi T, Sato Y, Niitsu Y. Colorectal cancer: Genetics of development and metastasis. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:185-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Yamasaki M, Takemasa I, Komori T, Watanabe S, Sekimoto M, Doki Y, Matsubara K, Monden M. The gene expression profile represents the molecular nature of liver metastasis in colorectal cancer. Int J Oncol. 2007;30:129-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | de Krijger I, Mekenkamp LJ, Punt CJ, Nagtegaal ID. MicroRNAs in colorectal cancer metastasis. J Pathol. 2011;224:438-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | De Angelis PM, Clausen OP, Schjølberg A, Stokke T. Chromosomal gains and losses in primary colorectal carcinomas detected by CGH and their associations with tumour DNA ploidy, genotypes and phenotypes. Br J Cancer. 1999;80:526-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Brenner BM, Rosenberg D. High-throughput SNP/CGH approaches for the analysis of genomic instability in colorectal cancer. Mutat Res. 2010;693:46-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Knösel T, Schlüns K, Stein U, Schwabe H, Schlag PM, Dietel M, Petersen I. Chromosomal alterations during lymphatic and liver metastasis formation of colorectal cancer. Neoplasia. 2004;6:23-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Nakao K, Shibusawa M, Ishihara A, Yoshizawa H, Tsunoda A, Kusano M, Kurose A, Makita T, Sasaki K. Genetic changes in colorectal carcinoma tumors with liver metastases analyzed by comparative genomic hybridization and DNA ploidy. Cancer. 2001;91:721-726. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Jass JR, Ajioka Y, Allen JP, Chan YF, Cohen RJ, Nixon JM, Radojkovic M, Restall AP, Stables SR, Zwi LJ. Assessment of invasive growth pattern and lymphocytic infiltration in colorectal cancer. Histopathology. 1996;28:543-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Solinas G, Marchesi F, Garlanda C, Mantovani A, Allavena P. Inflammation-mediated promotion of invasion and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29:243-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | López-Novoa JM, Nieto MA. Inflammation and EMT: An alliance towards organ fibrosis and cancer progression. EMBO Mol Med. 2009;1:303-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 488] [Cited by in RCA: 537] [Article Influence: 33.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Hou X, Gong R, Zhan J, Zhou T, Ma Y, Zhao Y, Zhang Y, Chen G, Zhang Z, Ma S, Chen X, Gao F, Hong S, Luo F, Fang W, Yang Y, Huang Y, Chen L, Yang H, Zhang L. p300 promotes proliferation, migration, and invasion via inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition in non-small cell lung cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Xiong H, Zhang ZG, Tian XQ, Sun DF, Liang QC, Zhang YJ, Lu R, Chen YX, Fang JY. Inhibition of JAK1, 2/STAT3 signaling induces apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, and reduces tumor cell invasion in colorectal cancer cells. Neoplasia. 2008;10:287-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 288] [Cited by in RCA: 350] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Cheng F, Su L, Yao C, Liu L, Shen J, Liu C, Chen X, Luo Y, Jiang L, Shan J, Chen J, Zhu W, Shao J, Qian C. SIRT1 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis in colorectal cancer by regulating Fra-1 expression. Cancer Lett. 2016;375:274-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Bian CX, Shi Z, Meng Q, Jiang Y, Liu LZ, Jiang BH. P70S6K 1 regulation of angiogenesis through VEGF and HIF-1alpha expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;398:395-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |