Published online Mar 21, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i11.1421

Peer-review started: January 30, 2019

First decision: February 13, 2019

Revised: February 17, 2019

Accepted: February 22, 2019

Article in press: February 22, 2019

Published online: March 21, 2019

Processing time: 49 Days and 22.2 Hours

Obstructed defecation syndrome (ODS) is a widespread disease in the world. Rectocele is the most common cause of ODS in females. Multiple procedures have been performed to treat rectocele and no procedure has been accepted as the gold-standard procedure. Stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) has been widely used. However, there are still some disadvantages in this procedure and its effectiveness in anterior wall repair is doubtful. Therefore, new procedures are expected to further improve the treatment of rectocele.

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of a novel rectocele repair combining Khubchandani’s procedure with stapled posterior rectal wall resection.

A cohort of 93 patients were recruited in our randomized clinical trial and were divided into two different groups in a randomized manner. Forty-two patients (group A) underwent Khubchandani’s procedure with stapled posterior rectal wall resection and 51 patients (group B) underwent the STARR procedure. Follow-up was performed at 1, 3, 6, and 12 mo after the operation. Preoperative and postoperative ODS scores and depth of rectocele, postoperative complications, blood loss, and hospital stay of each patient were documented. All data were analyzed statistically to evaluate the efficiency and safety of our procedure.

In group A, 42 patients underwent Khubchandani’s procedure with stapled posterior rectal wall resection and 34 were followed until the final analysis. In group B, 51 patients underwent the STARR procedure and 37 were followed until the final analysis. Mean operative duration was 41.47 ± 6.43 min (group A) vs 39.24 ± 6.53 min (group B). Mean hospital stay was 3.15 ± 0.70 d (group A) vs 3.14 ± 0.54 d (group B). Mean blood loss was 10.91 ± 2.52 mL (group A) vs 10.14 ± 1.86 mL (group B). Mean ODS score in group A declined from 16.50 ± 2.06 before operation to 5.06 ± 1.07 one year after the operation, whereas in group B it was 17.11 ± 2.57 before operation and 6.03 ± 2.63 one year after the operation. Mean depth of rectocele decreased from 4.32 ± 0.96 cm (group A) vs 4.18 ± 0.95 cm (group B) preoperatively to 1.19 ± 0.43 cm (group A) vs 1.54 ± 0.82 cm (group B) one year after operation. No other serious complications, such as rectovaginal fistula, perianal sepsis, or deaths, were recorded. After 12 mo of follow-up, 30 patients’ (30/34, 88.2%) final outcomes were judged as effective and 4 (4/34, 11.8%) as moderate in group A, whereas in group B, 30 (30/37, 81.1%) patients’ outcomes were judged as effective, 5 (5/37, 13.5%) as moderate, and 2 (2/37, 5.4%) as poor.

Khubchandani’s procedure combined with stapled posterior rectal wall resection is an effective, feasible, and safe procedure with minor trauma to rectocele.

Core tip: Rectocele is one of most common causes of obstructed defecation syndrome (ODS) in females. A diversity of procedures has been performed to treat rectocele. Stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) is more often used among all the procedures for its simpleness. However, it is not the gold-standard procedure since its effect of anterior wall repair is doubted. We performed a novel procedure combining Khubchandani’s procedure and stapled posterior wall resection to treat rectocele. We compared the ODS score, rectocele depth, and complications between our procedure and STARR. Our procedure was proved to be safe and effective for treating rectocele.

- Citation: Shao Y, Fu YX, Wang QF, Cheng ZQ, Zhang GY, Hu SY. Khubchandani’s procedure combined with stapled posterior rectal wall resection for rectocele. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(11): 1421-1431

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i11/1421.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i11.1421

Obstructed defecation syndrome (ODS), which is more common in females[1], is one of the most widespread diseases in the world. The symptoms, such as difficult evacuation, prolonged or infrequent defecation, sense of incomplete evacuation, difficult evacuation without hand assistance, and perineal heaviness, significantly lower the life quality of ODS patients. The etiology of ODS can be functional disorders or rectal anatomy abnormality such as rectocele with or without rectal prolapse[2]. Although the incidence of rectocele is still illusive, approximately 30%-71% females suffer from the disease[3]; rectocele, pelvic floor[4] disease, and rectal mucosal prolapse are the most common causes of ODS in approximately 80% of female patients[5]. Approximately 54% of ODS patients suffer from both mucosal prolapse and rectocele. Several procedures for rectocele resection have been reported during the past years[6-10], and among them stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) procedure was more often used. However, the STARR procedure still has its disadvantages[11,12], and no surgical technique has been widely adopted as the gold-standard procedure for treatment of rectocele[13-16], as well as rectocele combined with rectal prolapse. Our department developed a new procedure that combined Khubchandani’s procedure[10] with stapled posterior rectal wall resection (KSPRWR) in 42 female patients with ODS caused by rectocele combined with or without rectal mucosal prolapse to evaluate and compare its safety and effectiveness with the STARR procedure.

From January 2014 to January 2017, 93 consecutive female patients who suffered from ODS caused by rectocele underwent surgery at Qilu Hospital of Shandong University. Their median age was 48.56 ± 13.22 (mean ± standard deviation, ranging from 22 to 79) years and their average duration of constipation was 2.27 ± 1.02 (6 mo to 4 years) years. They had an ODS score > 10[17] with a rectocele depth > 2 cm, and failed to respond to conservative measures, such as diet therapy, laxatives, prokinetic medicine, or biofeedback therapy[18]. All patients were randomly divided into two groups with ODS score and rectocele depth paired. Forty-two patients underwent KSPRWR (group A) and 51 patients underwent the STARR procedure (group B). All symptoms coincided with Rome III diagnostic criteria[19]. All patients signed a medical consent form before entering the trial.

Patients had a rectocele depth > 2.0 cm and an ODS score > 10 but had not received any medical treatment, or patients did not undergo operation due to health or personal reason were excluded from our trial. Defecography, colonoscopy, transmission test, and rectal and canal manometry were performed to exclude slow transit constipation, rectal or colorectal carcinoma, complete rectal prolapse, enterocele, inflammatory bowel disease, severe fecal incontinence, and pelvic floor dyssynergia. Patients with an ODS score < 10 or a depth of rectocele < 2.0 cm, which was shown on defecography, were not recruited in our study. Patients who failed to perform the follow-up were not take into the final analysis.

Preoperative procedure: An enema was administered the night before the surgery and another on the morning of the surgery. Other preoperative preparations included perioperative antibiotics and insertion of a urinary catheter.

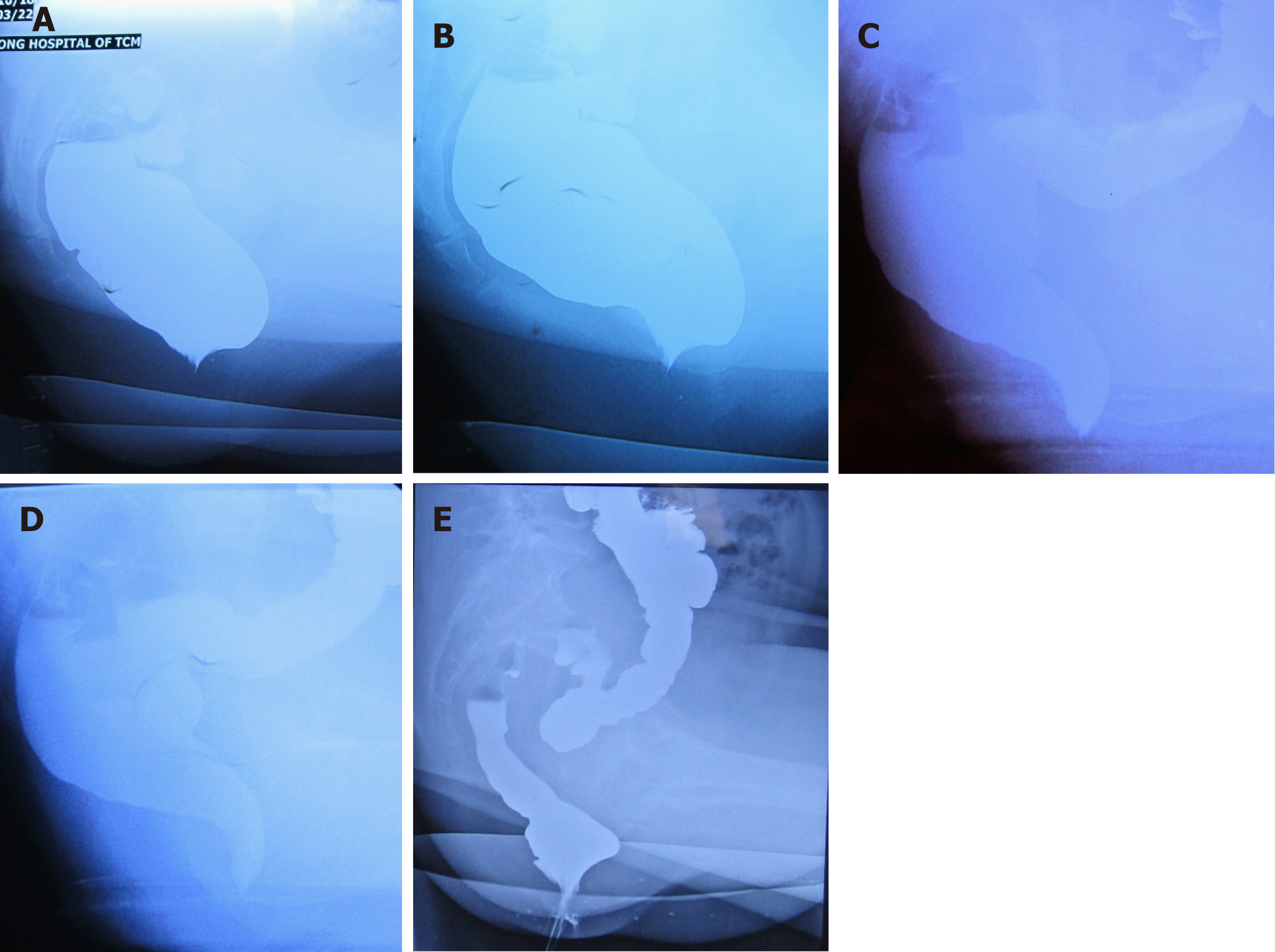

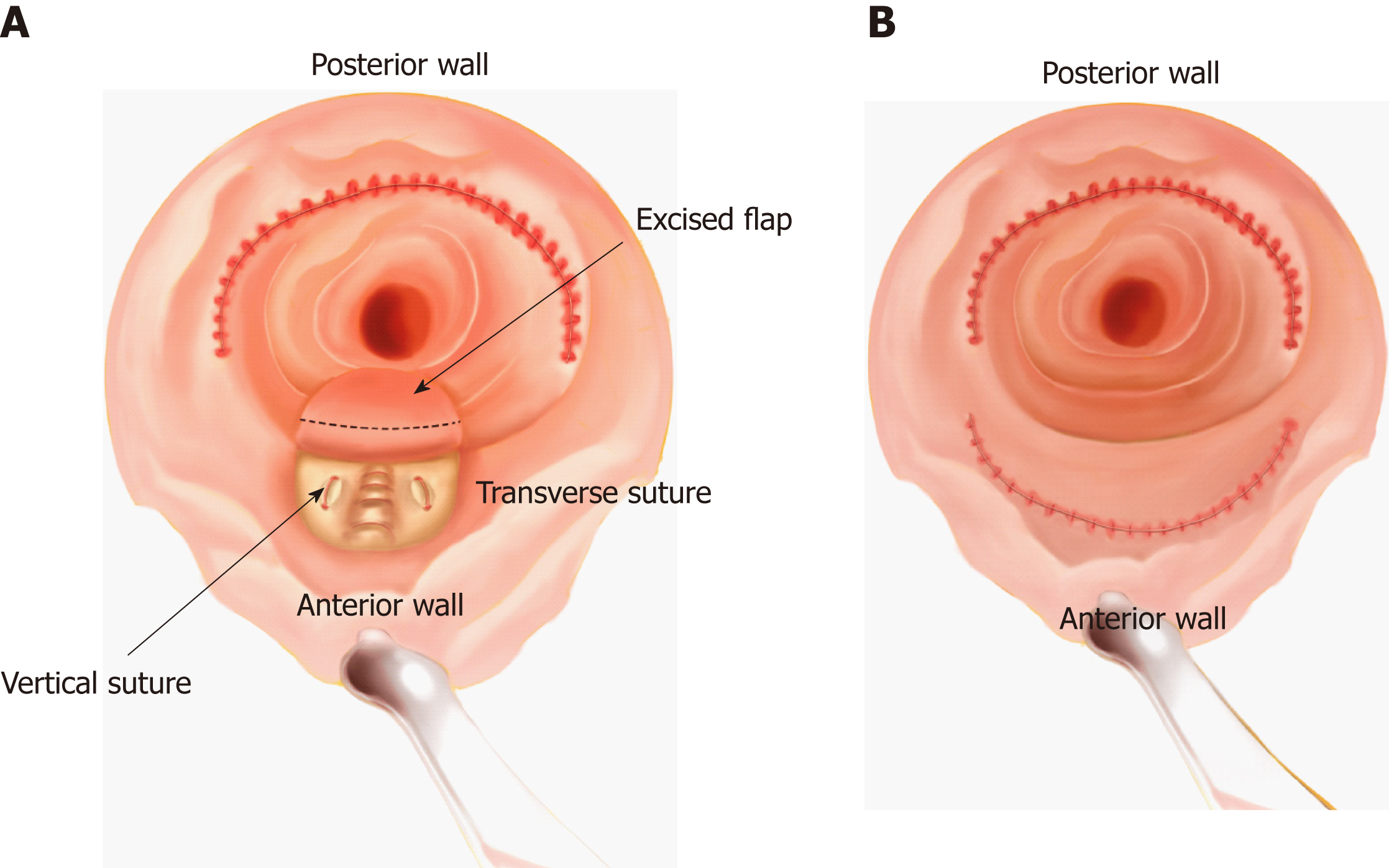

KSPRWR procedure: The patients received spinal anesthesia and were placed in the prone jackknife position. The procedure comprised two steps. Step 1 included performing stapled posterior rectal wall resection, as follows: We placed a circular anal dilator to loosen the anal canal and then inserted a half-purse string suture, which only included the mucosa and the submucosa, clockwise from 8 o’clock to 4 o’clock using a 2-0 absorbable suture at about 4 cm above the dentate line on the posterior wall of the anus. We placed the anvil of the stapling instrument (EEATM Auto SutureTM Hemorrhoid and Prolapse Stapler wit DST SeriesTM Technology, 3.3-3.5 mm) above the half-purse string and inserted a small intestinal spatula into the anus with the distant edge above the half-purse string to protect the anterior wall. The stapler was adjusted until the half-purse string lay on the shaft of the stapler. We then closed and fired the stapler and held it closed for 15 s to aid hemostasis. The stapler was opened to its maximum and withdrawn. The posterior rectal wall was resected as a half circle. In step 2, we performed the procedure as reported by Khubchandani[20]: 1:1000 adrenaline was injected into the mucosa of the anterior rectal wall to aid hemostasis. A transverse incision was made at the dentate line with a length of 2-3 cm but not too close to the staple line, and at the edge of the transverse incision two vertical incisions were made and extended into the anus for about 7 cm. It is very important that the incision reaches the muscular layer. Thus, a U-shaped mucomuscular flap was obtained and the flap was freed from the mucosal layer with meticulous hemostasis. Furthermore, three to five interrupted transverse sutures, which started from the dentate line to the edge of the flap using 3-0 polyglycolic acid absorbable stitches, were placed at the mucosal layer to plicate the flabby rectovaginal septum, thus strengthening the anterior wall. Then two vertical sutures, which started at the proximal and ended at the distal points of the incision, were made to plicate the anterior rectal wall. During suturing, the guidance of the finger into the vagina was essential to prevent penetration of the suture into the vaginal mucosa. Most part of the flap was resected to further strengthen the anterior wall and the transverse and vertical incisions were sewed using interrupted sutures (Figure 1).

STARR procedure: Posterior wall repair was the same as that for the KWPRWR procedure. The same method was used to repair the anterior rectal wall. The staple line of the posterior wall was 1-2 cm deeper into the anus than that of the anterior wall (Figure 2).

Postoperative procedure: A drainage tube circled by three layers of Vaseline pledget was inserted into the anus as an anal plug for hemostasis and was removed on the second day after operation. The urinary catheter was removed on the second day after operation.

The complications of the operation (e.g., postoperative bleeding, anal fissure, rectal stricture, incontinence to flatus, persistent pain, etc.), the depth of the rectocele, and the ODS scores were recorded before and after operation. The follow-up was performed at 1, 3, 6, and 12 mo after operation. Follow-up was discontinued in the following situations: unable to return for a check-up at the follow-up time point, severe diseases, mental illness, postoperative operation, and death.

After 12 mo of follow-up, procedure effectiveness in patients with an ODS score < 10 and a depth of rectocele < 2.0 cm, but without other complications that were included in Rome III diagnostic criteria (e.g., incontinence to flatus) was considered effective. Procedure effectiveness in patients with complications in Rome III diagnostic criteria but having an ODS score < 10 and a depth of rectocele < 2.0 cm was considered moderate, and procedure effectiveness in patients with an ODS score > 10 or a depth of rectocele > 2.0 cm was considered poor.

All data are expressed as the mean± standard deviation. Statistical analyses were performed using paired t-test with SPSS 22.0, and the level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

In group A, eight patients failed to perform our follow-up program; therefore, there were 34 patients in the final analysis with at least 12 mo of follow-up. In group B, there were 37 patients in the final analysis. All females suffered from rectocele, and 23 (23/34, 67.6%) patients in group A and 24 (24/37, 64.9%) in group B suffered from both rectocele and rectal prolapse. Mean operative time was 41.47 ± 6.43 min (group A) vs 39.24 ± 6.53 (group B). Mean hospital stay was 3.15 ± 0.70 d (group A) vs 3.14 ± 0.54 d (group B), and mean blood loss was 10.91 ± 2.52 mL (group A) vs 10.14 ± 1.86 mL (group B). No significant differences were found regarding operative time, hospital stay, or blood loss between the two groups (Table 1).

| n/mean ± SD | ||

| KSPRWR | STARR | |

| Age (yr) | 46.59 ± 9.41 | 50.38 ± 15.86 |

| Gender | Female | Female |

| Combined with rectal prolapse | 23 | 24 |

| History of disease (yr) | 2.35 ± 0.93 | 2.20 ± 1.11 |

| Procedure (in final analysis) | 34 | 37 |

| Operative time (min) | 41.47 ± 6.43 | 39.24 ± 6.53 |

| Estimated blood loss (mL) | 10.91 ± 2.52 | 10.14 ± 1.86 |

| Hospital stay (d) | 3.15 ± 0.70 | 3.14 ± 0.54 |

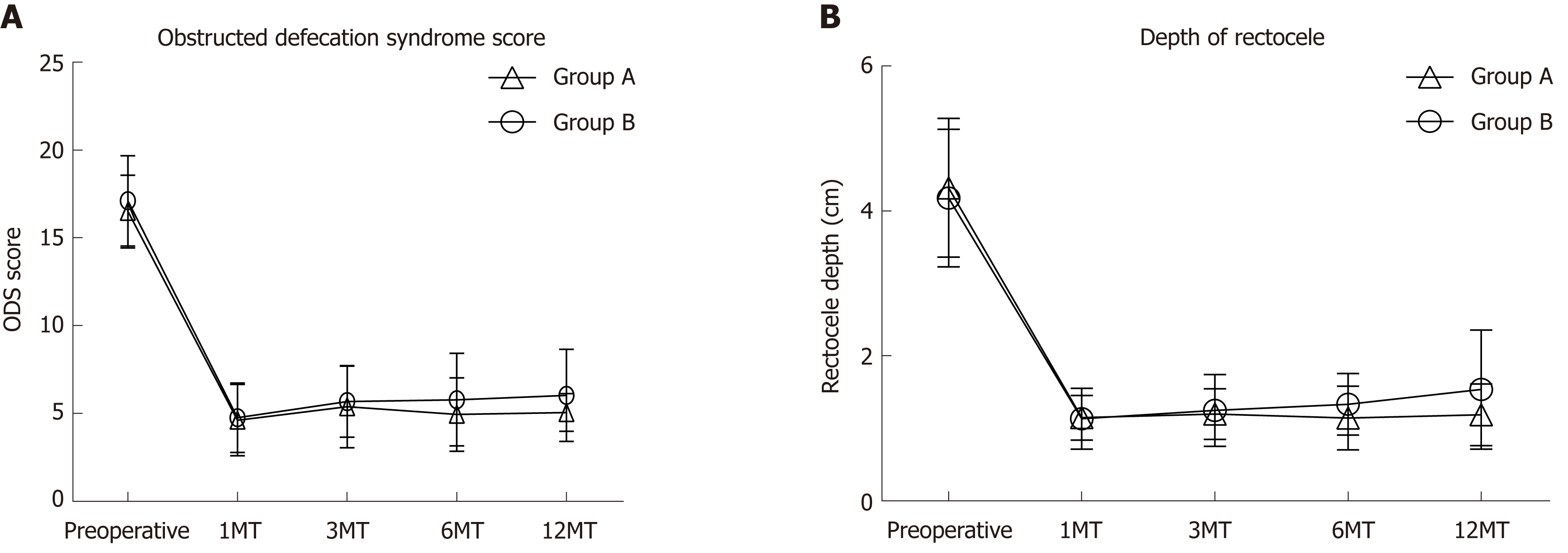

The minimum follow-up duration was 12 mo. At this follow-up, ODS scores, depth of rectocele, and complications of operation were recorded. Mean ODS score before the operation was 16.50 ± 2.06 (group A) vs 17.11 ± 2.57 (group B) (Figure 3A). Mean ODS score 1 mo after operation (1MT), 3 mo after operation (3MT), 6 mo after operation (6MT), and 1 year after operation (12MT) in groups A and B were 4.62 ± 2.03 vs 4.76 ± 1.98, 5.38 ± 2.34 vs 5.68 ± 2.03, 4.94 ± 2.09 vs 5.78 ± 2.64, and 5.06 ± 1.07 vs 6.03 ± 2.63, respectively. Compared with the preoperative ODS scores, ODS scores at 1MT, 3MT, 6MT, and 12MT all had significant differences in both groups A and B (P < 0.05) (Table 2). In the pairwise comparison of postoperative groups (1MT, 3MT, 6MT, and 12MT) in each group, there were no significant differences (P > 0.05). There was a statistical difference in 12MT ODS scores between groups A and B. The ODS scores of two patients were over 10 at 12MT in group B.

| ODS score | Rectocele depth | ||||

| Group A | Group B | Group A | Group B | ||

| Comparison within group | a | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 |

| b | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| c | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| d | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| e | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | |

| f | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | |

| g | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | |

| h | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | P>0.05 | |

| i | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | |

| j | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | |

| Comparison between groups | k | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | ||

| l | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | |||

| m | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | |||

| n | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | |||

| o | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |||

Mean preoperative depth of rectocele was 4.32 ± 0.96 cm (group A) vs 4.18 ± 0.95 cm (group B) (Figure 3B). Mean ODS scores at 1MT, 3MT, 6MT, and 12MT were 1.15 ± 0.31 cm (group A) vs 1.13 ± 0.42 cm (group B), 1.20 ± 0.35 cm vs 1.25 ± 0.50 cm, 1.14 ± 0.44 cm vs 1.33 ± 0.42 cm, and 1.19 ± 0.43 cm vs 1.54 ± 0.82 cm, respectively. Compared with the preoperative rectocele depth, rectocele depth at 1MT, 3MT, 6MT, and 12MT all showed statistically significant differences in both groups A and B (P < 0.05) (Table 2). There were no significant differences (P > 0.05) in the pairwise comparison of the postoperative groups (1MT, 3MT, 6MT, and 12MT) in each group. A statistical difference was found in 12MT depth of rectocele between the two groups. One patient’s rectocele depth was over 2 cm at 12MT (Figure 1E).

In group A, five (5/34, 14.7%) patients had vaginal discomfort in the first week after operation (Table 3). Retention of urine after removal of the ureter was seen in three (3/34, 8.8%) patients. Postoperative bleeding occurred in one (1/34, 2.9%) patient after the anal plug was removed, but blood loss was approximately less than 5 mL and stopped spontaneously. The other complications that occurred in the first week after operation were nausea (7/34, 20.6%), anal fissures (7/34, 20.6%), incontinence to flatus (2/34, 5.9%), defecatory urgency (2/34, 5.9%), and persistent pain(13/34, 38.2%). One patient felt defecatory urgency after surgery and relieved at 6MT, while three patients complained about defecatory urgency since 6MT and did not relieve at 12MT. No occurrence of staple line dehiscence, rectal stricture, rectovaginal fistula, or perianal sepsis was recorded. No deaths were reported 12 mo after operation.

| Complication | First week | 1 mo after operation | 3 mo after operation | 6 mo after operation | 12 mo after operation |

| Nausea | 7 (20.6%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Retention of urine after urinary catheter removal | 3 (8.8%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anal fissure | 7 (20.6%) | 5 (14.7%) | 2 (5.9%) | 0 | 0 |

| Incontinence to flatus | 2 (5.9%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Postoperative bleeding | 1 (2.9%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Defecatory urgency | 2 (5.9%) | 1 (2.9%) | 1 (2.9%) | 3 (8.8%) | 3 (8.8%) |

| Persistent pain | 13 (38.2%) | 4 (11.8%) | 2 (5.9%) | 2 (5.9%) | 1 (2.9%) |

| Vagina discomfort | 5 (14.7%) | 2 (5.9%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Recurrence | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

In group B, nine (9/37, 24.3%) patients had nausea after operation and no postoperative bleeding occurred (Table 4). The most common complications in the first week after operation in group B was persistent pain (12/37, 32.4%), and two (2/37, 5.4%) patients continued to experience anal pain 12 mo after operation. The other complications that occurred in the first week after operation were retention of urine after urinary catheter removal (1/37, 2.7%), anal fissures (5/37, 13.5%), incontinence to flatus (2/37, 5.4%), and defecatory urgency (2/37, 5.4%). No occurrence of staple line dehiscence, rectal stricture, rectovaginal fistula, or perianal sepsis was recorded. No deaths were reported 12 mo after operation. One patient had the feeling of incontinence to flatus and another patient felt defecatory urgency until 3 mo after surgery and they all relieved at 6MT. Two patients had incontinence to flatus and defecatory urgency since 6MT, which further worsened at 12MT. The follow-up revealed that their ODS scores were more than 10. The rectocele depth in one of the patients was more than 2.0 cm. Thus, recurrence was reported in these two patients.

| Complication | First week | 1 mo after operation | 3 mo after operation | 6 mo after operation | 12 mo after operation |

| Nausea | 9 (24.3%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Retention of urine after urinary catheter removal | 1 (2.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anal fissure | 5 (13.5%) | 5 (13.5%) | 2 (5.4%) | 0 | 0 |

| Incontinence to flatus | 2 (5.4%) | 1 (2.7%) | 1 (2.7%) | 3 (8.1%) | 4 (10.8%) |

| Postoperative bleeding | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Defecatory urgency | 2 (5.4%) | 1 (2.7%) | 1 (2.7%) | 2 (5.4%) | 3 (8.1%) |

| Persistent pain | 12 (32.4%) | 3 (8.1%) | 2 (5.4%) | 2 (5.4%) | 2 (5.4%) |

| Vagina discomfort | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Recurrence | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (5.4%) |

After 12 mo of follow-up, 30 patients’ (30/34, 88.2%) final outcomes were judged as effective and 4(4/34, 11.8%) as moderate in group A, whereas in group B, 30 (30/37, 81.1%) patients’ outcomes were judged as effective, 5 (5/37, 13.5%) as moderate, and 2 (2/37, 5.4%) as poor.

Rectocele is one of the most common causes of female ODS[21,22]. The reason for the high morbidity of rectocele might be that the internal anal sphincter is shorter and formed distally in the anterior upper anal canal, which might weaken the anorectal junction that is devoid of support structure in females[23]. A substantial number of procedures via the vagina[24,25], perineum[26], anus[6,27], or abdomen[28,29] have been reported to repair the rectocele through different routes, and none of the methods were adopted as the gold-standard operation[25]. Longo[6,7] performed STARR, which has been ameliorated and used owing to its simple, easy, and fast operation[30-32] since the past years. The STARR procedure aims to rebuild the rectal volume and strengthen the anterior rectal wall through linear resection and suturing of the frail rectal mucosa, submucosa, and superficial muscular layer[7]. The entire procedure requires two staplers and is simple to perform. Moreover, it effectively rebuilds the rectal volume by resection of the prolapsed tissue. However, there is an ongoing debate between the supporters and the opponents of STARR as multiple postoperative complications have been reported[31,33-37] after STARR. Some long-term follow-up studies[11,38] revealed that the ODS score of patients who underwent the STARR procedure had a smooth increase after operation. Moreover, the effectiveness of anterior wall repair using the STARR procedure has been questioned by some opponents[2,39]. They argue that the resection of the muscular layer in the STARR procedure is not adequate to strengthen the anterior rectal wall; thus, recurrence can be expected in the future. Some supporters of the STARR procedure also admitted that, so several modified STARR procedures were invented[34,35] to ensure the effectiveness of anterior wall repair. However, none of these modified procedures has been accepted as a gold-standard procedure as the long-term curative effect is not clear.

Khubchandani et al[10,20] reported his procedure of rectocele repair with satisfactory outcomes. This procedure strengthens the anterior rectal wall through transverse suturing in the muscular layer. However, rectal prolapse combined with rectocele, with morbidity ranging from 24% to 54%[5,11,18] , was not considered in their procedure. Moreover, Khubchandani et al[20] found that isolated anterior rectal wall repair in the rectocele without rectal prolapse may cause hypotonus of the posterior wall, which may induce posterior rectal wall intussusception after operation. As the effect of rebuilding the rectal volume of STARR procedure is clear, we decided to combine the two procedures. We used Khubchandani’s procedure for anterior wall repair to strengthen the rectal wall and stapled posterior rectal wall resection to resect the potentially or already existing excessive tissue of the posterior wall to restore anatomy and correct the tension of posterior rectal wall in rectocele patients with or without rectal prolapse.

There were no significant differences in hospital stay, operative time, or blood loss between the two groups, which indicated that the trauma and difficulty of the two operations have no significant difference. The most common postoperative complication of STARR was persistent anal pain because of the staple line. In our research, one patient had persistent pain at 12MT in group A and two patients had persistent pain at 12MT in group B. Nausea was the second most common complication in both groups, especially in women aged 45-55 years. All episodes of nausea occurred in the first three days after operation and all were relieved one week after the operation, which might be related to hormonal standard[37]. Rectal vaginal fistula is a very serious complication in both procedures, but no rectal vaginal fistula was recorded in both groups. Our experience was that while performing anterior wall repair, a guidance of the finger into the vagina is essential to prevent the damage. No occurrence of staple line dehiscence, rectal stricture, or perianal sepsis was recorded in our research. Vagina discomfort is a rare but annoying complication in Khubchandani’s procedure[20], which is probably due to the suture in the rectovaginal septum. In our study, five patients experienced vagina discomfort in the first week after operation, and the discomfort was relieved at 3MT. Anal fissure is another common complication after rectocele surgery[11,38,40,41], especially using the STARR procedure. More patients suffered anal fissure in group A in the first week after operation, but the number became the same after that. No anal fissure was recorded at 12MT in either group.

In our study, the mean ODS score of the patients who underwent the STARR procedure significantly dropped to a normal level at 1MT. However, although the ODS scores of the STARR group remained within normal levels, they continued to increase smoothly from 3MT to 12MT. Accompanied with the increasing ODS score, the depth of the rectocele also increased from 3MT to 12MT. However, in patients who underwent our procedure, the ODS score and rectocele depth dropped to normal levels after surgery, remained at a certain level at 3MT and 6MT, and slightly increased within normal standard at 12MT. Recurrence did not occur in any patient in group A, but two patients in group B had recurrence at 12 MT. Defecography showed that the rectocele depth of one patient was more than 2 cm. Interestingly, these two patients both had deep preoperative rectocele which was around 5.5 cm in depth, thus indicating that the STARR procedure might have a less effect than expected in anterior wall repair in the patients with deep rectocele. Furthermore, defecatory urgency and incontinence to flatus were the most common complaints after operation[9,39,42,43]. More patients in group B experienced these symptoms at 12MT than those in group A. Moreover, although the mean ODS score and rectocele depth were within normal levels in both groups, they were significantly lower in group A than in group B at 12MT, thus indicating that the patients who underwent our procedure might have a better outcome in the mid-long period.

In this research, we gained initial experience of the new procedure. There are four key points of successfully carrying out this operation. The first one was to make sure that the transverse and vertical suture in the anterior wall was in the muscular layer. This can ensure the effectiveness of anterior wall repair. The second key point was that the vertical edge of the U-shaped flap should not overlap with the stapler suture on the posterior wall in the case of postoperative rectal stricture. The third key point was excising most part but not all of the U-shape flap and leaving proper part of the flap. This was significant to avoid rectal stricture. The last key point of the procedure was using the finger as guidance in the vagina to prevent damage. As we suture the anterior wall, there is a possibility of hurting the vagina; therefore, the guidance is quite important. This requires skill and practice.

Although our procedure was not less effective than the STARR procedure in a short to middle term, there were still some limitations in our research. We did not perform any procedure or treatment on the recurrent patients since we lost the contact with them after the last check-up, thus we could not explore if our procedure would be effective for recurrent rectocele. Besides, we need more experience on selecting a more suitable type of stitch for suture in rectal vaginal septum so that less vagina discomfort would happen after our surgery. Furthermore, we did not set subgroups to analyze different outcomes of the two procedures in patients with different rectocele depth or ODS scores. A larger number of patients, a multiple center study, and a longer-term follow-up are needed to further prove its effectiveness and safety.

In conclusion, Khubchandani’s procedure combined with stapled posterior rectal wall resection is an effective and safe procedure with minor trauma, short hospital stay, and low cost for rectocele treatment, especially for rectocele combined with rectal prolapse. It is not less effective compared with the STARR procedure, which may be an optional procedure in the treatment of rectocele with rectal prolapse. We plan to perform a longer period follow-up and recruit larger number of patients in a multiple center, which aims at determining long-term postoperative quality of life in female patients, to further verify the safety and effectiveness of the procedure in the future.

Obstructed defecation syndrome (ODS) has a serious influence on health and life quality of patients. Rectocele is one of the main causes of ODS, which has an approximate incidence of 30%-71%. Multiple procedures have been performed to treat rectocele, but no one has been considered as the gold-standard treatment.

Stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) has been quite popular in treating rectocele for its simpleness. However, debate on STARR has never stopped. Opponents doubted its effectiveness in anterior wall repair and declared that multiple serious postoperative complications occurred. Khubchandani performed his procedure for rectocele with a satisfying effect, but it did not take rectal prolapse into consideration and may potentially induce rectal prolapse in posterior rectal wall. Therefore, we combined Khubchandani’s procedure and stapled posterior rectal wall resection together.

In this study, we evaluated the efficacy and safety of a novel rectocele repair which combined Khubchandani’s procedure with stapled posterior rectal wall resection. The results of the study will guide the treatment for rectocele in future.

From January 2014 to January 2017, 93 patients were recruited into our randomized clinical trial and divided into two different groups in a randomized manner. Forty-two patients (group A) underwent Khubchandani’s procedure with stapled posterior rectal wall resection (KSPRWR) and 51 patients (group B) underwent the stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) procedure. Follow-up was performed at 1, 3, 6, and 12 mo after the operation. Preoperative and postoperative ODS scores and depth of rectocele, postoperative complications, blood loss, and hospital stay of each patient were documented. All data were analyzed statistically to evaluate the efficiency and safety of our procedure.

No significant differences were found in blood loss, hospital stay, or operative time. Compared with preoperative ODS scores and rectocele depth, postoperative ODS scores and rectocele depth in the two groups were statistically lower, which proved the effectiveness of our procedure. There were significant differences when comparing the ODS score and rectocele depth 1 year after operation, which were significantly lower in group A than in group B, thus indicating that group A might have better outcomes in future.

KSPRWR is an effective and safe procedure with minor trauma, short hospital stay, and low cost for rectocele treatment, especially for rectocele combined with rectal prolapse. It should be considered as an alternative operation for rectocele.

A long-term follow-up, a larger number of patients, and a multiple center clinical trial are expected in the future to further prove the effectiveness and safety of this procedure.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Boeckxstaens GE, Fernandez JM, Mulvihill SJ, Schmidt J S- Editor: Yan JP L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Heaton KW, Radvan J, Cripps H, Mountford RA, Braddon FE, Hughes AO. Defecation frequency and timing, and stool form in the general population: A prospective study. Gut. 1992;33:818-824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 493] [Cited by in RCA: 491] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mustain WC. Functional Disorders: Rectocele. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2017;30:63-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Schmidlin-Enderli K, Schuessler B. A new rectovaginal fascial plication technique for treatment of rectocele with obstructed defecation: A proof of concept study. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:613-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zbar AP, Lienemann A, Fritsch H, Beer-Gabel M, Pescatori M. Rectocele: Pathogenesis and surgical management. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2003;18:369-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pescatori M, Spyrou M, Pulvirenti d'Urso A. A prospective evaluation of occult disorders in obstructed defecation using the 'iceberg diagram'. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:785-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Longo A. Treatment of hemorrhoids disease by reduction of mucosa and hemorrhoidal prolapse with a circular suturing device: A new procedure; Proceedings of the 6th World Congress of Endoscopic Surgery; 1998 Jun 3-6; Rome, Italy. Bologna: Monduzzi Publishing 1998; 777-784. |

| 7. | Longo A. Obstructed defecation because of rectal pathologies. 2004;. |

| 8. | Bresler L, Rauch P, Denis B, Grillot M, Tortuyaux JM, Regent D, Boissel P, Grosdidier J. [Treatment of sub-levator rectocele by transrectal approach. Value of the automatic stapler with linear clamping]. J Chir (Paris). 1993;130:304-308. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Hasan HM, Hasan HM. Stapled transanal rectal resection for the surgical treatment of obstructed defecation syndrome associated with rectocele and rectal intussusception. ISRN Surg. 2012;2012:652345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Khubchandani IT, Sheets JA, Stasik JJ, Hakki AR. Endorectal repair of rectocele. Dis Colon Rectum. 1983;26:792-796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pescatori M, Gagliardi G. Postoperative complications after procedure for prolapsed hemorrhoids (PPH) and stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) procedures. Tech Coloproctol. 2008;12:7-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Schiano di Visconte M, Nicolì F, Pasquali A, Bellio G. Clinical outcomes of stapled transanal rectal resection for obstructed defaecation syndrome at 10-year follow-up. Colorectal Dis. 2018;20:614-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Beck DE, Allen NL. Rectocele. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2010;23:90-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Brusciano L, Limongelli P, Tolone S, del Genio GM, Martellucci J, Docimo G, Lucido F, Docimo L. Technical Aspect of Stapled Transanal Rectal Resection. From PPH-01 to Contour to Both: An Optional Combined Approach to Treat Obstructed Defecation? Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:817-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ellis CN, Essani R. Treatment of obstructed defecation. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2012;25:24-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wexner SD. Reaching a Consensus for the Stapled Transanal Rectal Resection Procedure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Altomare DF, Spazzafumo L, Rinaldi M, Dodi G, Ghiselli R, Piloni V. Set-up and statistical validation of a new scoring system for obstructed defaecation syndrome. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:84-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lembo A, Camilleri M. Chronic constipation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1360-1368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 564] [Cited by in RCA: 515] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rome Foundation. Guidelines--Rome III Diagnostic Criteria for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2006;15:307-312. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Khubchandani IT, Clancy JP, Rosen L, Riether RD, Stasik JJ. Endorectal repair of rectocele revisited. Br J Surg. 1997;84:89-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bozkurt MA, Kocataş A, Karabulut M, Yırgın H, Kalaycı MU, Alış H. Two Etiological Reasons of Constipation: Anterior Rectocele and Internal Mucosal Intussusception. Indian J Surg. 2015;77:868-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Stewart JR, Hamner JJ, Heit MH. Thirty Years of Cystocele/Rectocele Repair in the United States. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2016;22:243-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Fritsch H, Hötzinger H. Tomographical anatomy of the pelvis, visceral pelvic connective tissue, and its compartments. Clin Anat. 1995;8:17-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Shafik AA, El Sibai O, Shafik IA. Rectocele repair with stapled transvaginal rectal resection. Tech Coloproctol. 2016;20:207-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Stojkovic SG, Balfour L, Burke D, Finan PJ, Sagar PM. Does the need to self-digitate or the presence of a large or nonemptying rectocoele on proctography influence the outcome of transanal rectocoele repair? Colorectal Dis. 2003;5:169-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Watson SJ, Loder PB, Halligan S, Bartram CI, Kamm MA, Phillips RK. Transperineal repair of symptomatic rectocele with Marlex mesh: A clinical, physiological and radiologic assessment of treatment. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;183:257-261. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Maurel J, Gignoux M. [Surgical treatment of supralevator rectocele. Value of transanal excision with automatic stapler and linear suture clips]. Ann Chir. 1993;47:326-330. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Fox SD, Stanton SL. Vault prolapse and rectocele: Assessment of repair using sacrocolpopexy with mesh interposition. BJOG. 2000;107:1371-1375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Thornton MJ, Lam A, King DW. Laparoscopic or transanal repair of rectocele? A retrospective matched cohort study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:792-798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lenisa L, Schwandner O, Stuto A, Jayne D, Pigot F, Tuech JJ, Scherer R, Nugent K, Corbisier F, Espin-Basany E, Hetzer FH. STARR with Contour Transtar: Prospective multicentre European study. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11:821-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Liu WC, Wan SL, Yaseen SM, Ren XH, Tian CP, Ding Z, Zheng KY, Wu YH, Jiang CQ, Qian Q. Transanal surgery for obstructed defecation syndrome: Literature review and a single-center experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:7983-7998. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ribaric G, D'Hoore A, Schiffhorst G, Hempel E; TRANSTAR Registry Study Group. STARR with CONTOUR® TRANSTAR™ device for obstructed defecation syndrome: One-year real-world outcomes of the European TRANSTAR registry. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:611-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Arroyo A, González-Argenté FX, García-Domingo M, Espin-Basany E, De-la-Portilla F, Pérez-Vicente F, Calpena R. Prospective multicentre clinical trial of stapled transanal rectal resection for obstructive defaecation syndrome. Br J Surg. 2008;95:1521-1527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Lin HC, Chen HX, He QL, Huang L, Zhang ZG, Ren DL. A Modification of the Stapled TransAnal Rectal Resection (STARR) Procedure for Rectal Prolapse. Surg Innov. 2018;25:578-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Ren XH, Yaseen SM, Cao YL, Liu WC, Shrestha S, Ding Z, Wu YH, Zheng KY, Qian Q, Jiang CQ. A transanal procedure using TST STARR Plus for the treatment of Obstructed Defecation Syndrome: 'A mid-term study'. Int J Surg. 2016;32:58-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Tjandra JJ, Ooi BS, Tang CL, Dwyer P, Carey M. Transanal repair of rectocele corrects obstructed defecation if it is not associated with anismus. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1544-1550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Vahabi S, Abaszadeh A, Yari F, Yousefi N. Postoperative pain, nausea and vomiting among pre- and postmenopausal women undergoing cystocele and rectocele repair surgery. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2015;68:581-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Naldini G. Serious unconventional complications of surgery with stapler for haemorrhoidal prolapse and obstructed defaecation because of rectocoele and rectal intussusception. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:323-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Titu LV, Riyad K, Carter H, Dixon AR. Stapled transanal rectal resection for obstructed defecation: A cautionary tale. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1716-1722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Boccasanta P, Venturi M, Roviaro G. What is the benefit of a new stapler device in the surgical treatment of obstructed defecation? Three-year outcomes from a randomized controlled trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:77-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Zhang B, Ding JH, Zhao YJ, Zhang M, Yin SH, Feng YY, Zhao K. Midterm outcome of stapled transanal rectal resection for obstructed defecation syndrome: A single-institution experience in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:6472-6478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Bock S, Wolff K, Marti L, Schmied BM, Hetzer FH. Long-term outcome after transanal rectal resection in patients with obstructed defecation syndrome. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:246-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Guttadauro A, Chiarelli M, Maternini M, Baini M, Pecora N, Gabrielli F. Value and limits of stapled transanal rectal repair for obstructed defecation syndrome: 10 years-experience with 450 cases. Asian J Surg. 2018;41:573-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |